Abstract

The transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily is one of the most diversified cell signaling pathways and regulates many physiological and pathological processes. Recently, neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) was reported to bind and activate the latent form of TGF-β1 (LAP-TGF-β1). We investigated the role of NRP-1 on Smad signaling in stromal fibroblasts upon TGF-β stimulation. Elimination of NRP-1 in stromal fibroblast cell lines increases Smad1/5 phosphorylation and downstream responses as evidenced by up-regulation of inhibitor of differentiation (Id-1). Conversely, NRP-1 loss decreases Smad2/3 phosphorylation and its responses as shown by down-regulation of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and also cells exhibit more quiescent phenotypes and growth arrest. Moreover, we also observed that NRP-1 expression is increased during the culture activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), a liver resident fibroblast. Taken together, our data suggest that NRP-1 functions as a key determinant of the diverse responses downstream of TGF-β1 that are mediated by distinct Smad proteins and promotes myofibroblast phenotype.

Keywords: Cell Cycle, Fibroblast, Receptors, Signal Transduction, Transforming Growth Factor β (TGFβ), R-Smad Signaling, Neuropilin-1

Introduction

NRP-1 was initially discovered as a semaphorin co-receptor and vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF2/VEGF) co-receptor (1, 2). Recently, NRP-1 was shown to bind and activate latency-associated protein (LAP)-TGF-β1 and enhance regulatory T cell (Treg) activity (3). The extracellular domain of NRP-1 contains three structural motifs: two cubilin (CUB) homology domains (a1, a2), two coagulation factor V/VIII homology domains (b1, b2), and a meprin/A5-protein/PTPmu (MAM) domain (c) (4). The relatively short (about 40 amino acids) cytoplasmic domain lacks kinase motifs. Interestingly, NRP-1 has a similar intracellular domain as TGF-β receptor III (TGF-βRIII/β-glycan), and its homolog endoglin, with the PSD-95/Disc-large/ZO-1 (PDZ) binding motif (supplemental Fig. S1). Therefore, we hypothesize that NRP-1 may also serve as a TGF-β co-receptor that regulates TGF-β signaling.

TGF-β is one member of a superfamily of secreted proteins, which also includes activins and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs). TGF-β signaling is one of the most diversified signaling cascades, controlling many aspects of cell behavior, including cell division, differentiation, motility, and death. TGF-β receptors include type I (TβRI), type II (TβRII), and type III (TβRIII). TβRI and TβRII, which are serine/threonine kinase receptors, constitute a hetertetrameric core receptor complex, and TβRIII modulates signaling by regulating ligand binding to the core receptor complex. There are at least seven TβRIs (activin receptor-like kinase 1–7, ALK1–7), five TβRIIs (TGF-βRII, ActRIIA, ActRIIB, AMHRII, and BMPRII), and two TβRIIIs (β-glycan and endoglin). ALK-2, ALK3, ALK4, ALK5, and ALK6 are also known as ActR-I, BMPR-IA, ActR-IB, TGF-βRI, and BMPR-IB, respectively (5).

Upon TGF-β binding, TβRII activates and phosphorylates the TβRI, which then phosphorylates the receptor-regulated Smad (R-Smad) proteins (including Smad1, 2, 3, 5, and 8). Subsequently, the phosphorylated R-Smad protein forms a heteromeric complex with the co-Smad (Smad4) and translocates to the nucleus to regulate the target gene transcription (6–9). In addition to this canonical Smad pathway, TGF-β also activates Smad-independent signaling transduction pathways in a cell-type-specific manner, including Rho-ROCK1, Cdc42/Rac1- p21-activated kinase-2 (PAK2), c-Abl, and the mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR), JNK, and p38 MAPK (10). There are also R-Smad-dependent, but Smad4-independent pathways that mediate TGF-β signaling (11–13). The effects of TGF-β are highly dependent on cell type. For example, TGF-β inhibits epithelial cell proliferation but increases endothelial cell proliferation. As TGF-β signaling is transduced from the cell membrane, receptor expression levels and combinations on each cell type contribute to the outcome.

Initially, TGF-β was believed to activate only Smad2/3 through ALK5. Some cells, like endothelial cells, sequentially express ALK1 and ALK5, active Smad1/5/8, and Smad2/3, upon TGF-β binding. Recently, TGF-β was shown can active Smad1/5/8 and Smad2/3 in several types of cell including non-cancerous epithelial cells, fibroblasts and cancer cells (14–16). Activated Smad1/5/8 and Smad2/3 have different, and occasionally opposite, functions. The mechanisms that regulate the diversity of responses downstream from TGF-β are unknown. Here, we report that NRP-1 can promote divergent signaling that leads to differential Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 activation and downstream myofibroblast phenotypes. Hence, NRP-1 can control Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 signaling counterbalances and regulates diversified TGF-β signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

LX2 cells, pancreatic tumor stromal cells (PSCs), wild-type MEFs, and NRP-1−/− MEFs (17) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were serum-starved for 16 h before TGF-β and BMPS treatment.

Primary Stellate Cell Immortalization

To immortalize human pancreatic stellate cells from pancreatic tumor (pancreatic tumor stromal cells, PSCs), primary cells were incubated with amphotropic retrovirus containing SV40 large T antigen (kind gift from Dr. Mulligan at MIT) for 24 h under culture conditions. Media and virus were replenished 3–5 times to ensure viral uptake and gene incorporation. Heterogeneous populations of immortalized stellate cells were serially diluted and plated as single cells per well to establish clones. Immortalized stellate cells were frozen in cryoprotectant media containing 45% complete media, 50% FBS and 5% DMSO. We subsequently, characterized these cells by the presence of established markers. For this purpose, total RNA was extracted from cells according to the manufacturer's instructions using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase digestion (Qiagen). RNA (2 μg) was converted to cDNA using an oligo (dT) primer and SuperScriptTM III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Stellate specific markers primers were designed and PCR performed using Platinum TaqDNA Polymerase (Invitrogen). Cycle conditions were as follows: 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min. Positive bands were visualized on 1.5% agarose with ethidium bromide.

Antibodies and Other Reagents

NRP-1, Id-1, TβRII, and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA); Smad2, Smad5, p-Smad1/5, p-Smad2, p-Smad3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA); α-SMA was from Millipore (Billerica, MA); collagen I antibody was from Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc. (Gilbertsville, PA); PAI were from Novus Bio. (Littleton, CO) TGF-β1 was from Biolegend (San Diego, CA); BMP9 was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); BMP2 and BMP4 were from Senway Biotech (San Diego, CA) ALK5 inhibitors SB431542 and ALK5 inhibitors (2-(3-(6-methylpyridine-2-yl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine) were from Stemgent (Cambridge, MA).

siRNA and shRNA Transfection

siRNA for human NRP-1, TβRII, and control were from Qiagen, Inc. (Valencia, CA). siRNA transfection was performed by Hiperfect (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. shRNA for human NRP-1 and controls were from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL) and were prepared as previously described (18). The sequences of siRNA and shRNA are listed in supplemental materials and methods.

RNA Isolation and PCR

Total RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed by oligo (dT) priming using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad). Semiquantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed using the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosciences). The primer sequences used are listed in supplemental materials and methods.

Immunocytochemistry Staining

Cells grew on glass coverslips overnight and were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. The excess paraformaldehyde was quenched by incubating in 50 mm NH4Cl for 10 min. The cell membrane was permeabalized with 0.2% saponin for 10 min. 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS was used for blocking for 10 min at room temperature, and then incubated in primary antibody (1:200) overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibody was added for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The coverslip was mounted with mount medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and photographed using a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Preparation of Whole Cell Extracts

Cells were washed twice with cold PBS, lysed with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) with 1% proteinase inhibitor cocktails (PIC; Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% Halt phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Pierce), incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. Supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was measured by Bradford method (Bio-Rad Protein assay).

Western Blot

Proteins were denatured by adding 6× Laemmli SDS sample buffer and heating for 4 min. Equal amounts of total protein per lane were subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis followed by wet transfer of the protein to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was blocked by incubation in TBS-T buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat milk or BSA. The primary antibody was diluted in TBS-T containing 5% nonfat milk or BSA overnight at 4 °C, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was diluted in TBS-T and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Immunodetection was performed with the SuperSignal West Pico Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Immunoprecipitation Assays

500 μg of cell lysate, 1 or 2 μg of antibody, and 50 μl of protein A/G-coupled Sepharose beads were added to the tube at 4 °C overnight under agitation. Beads were washed in RIPA buffer three times, and 2× loading buffer was added to the beads. Mixtures were boiled at 95 to 100 °C for 4 min, and then centrifuged. The supernatant was retained for Western blotting.

Cell Proliferation Assay

LX2 (1 × 104) was seeded in 24-well plates, subjected to the siRNA treatment, and cultured for 2 days in DMEM plus 10% FBS. 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well, and, 4 h later, cells were washed with cold PBS, fixed with 100% cold methanol, and collected for the measurement of trichloroacetic acid-precipitable radioactivity.

Apoptosis Assay

Cell apoptosis assay was done using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis kit (BioVision; Mountain View, CA). Briefly, cells were detached using 0.5 mm EDTA in PBS. After PBS washing, cells were resuspended in 500 μl of 1× binding buffer. 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC, and 5 μl of propidium iodide (PI) were added and incubated at room temperature for 5 min in the dark. Samples were subjected to flow cytometry analysis.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

Luc-Id1 (obtained from Dr. Vivek Mittal, Weill Cornell Medical College), Luc-ARE and FAST-1, Luc-SBE were used. Briefly, 5 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well plate were transfected with siRNA in complete media. After 24 h, cells were serum-starved overnight, then transfected with 0.05 μg/well luciferase reporter plasmid and a 0.01 μg/well pRL-TK Renilla luciferase vector as the internal control. One hour after transfection, TGF-β was added for 20–24 h. Firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) and measured in a LB960 microplate luminometer. Data were expressed as the mean standard deviations of triplicate values.

Construction of the NRP-1 Expression Vector

NRP-1 cDNA in pcDNA3.1 plasmid was obtained from Dr. Shay Soker. The NRP-1 gene was subcloned into the pMMp retroviral vector. Virus preparation and infection were done as previously described (19).

RESULTS

NRP-1 Controls TGF-β-induced Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 Signaling Balance

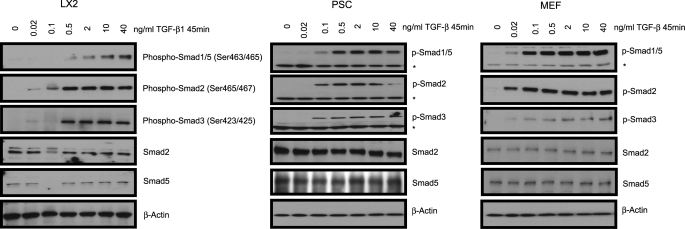

NRP-1 was shown to activate LAP-TGF-β1 (3). However, NRP-1 binds not only the LAP-TGF-β1, but also the active TGF-β1, indicating that NRP-1 has a role in active TGF-β1-mediated signaling (3). Hence, we hypothesized that NRP-1 might influence TGF-β-mediated signaling and downstream Smad phosphorylation. To this end, we utilized LX2 (a hepatic stellate cell line) cells, PSC, and MEF and determined the TGF-β-induced Smad activation in those cells. To characterize our model we first examined Smad phosphorylation downstream of TGF-β stimulation in our cell models. TGF-β stimulation led to a concentration-dependent Smad1/5 (Ser-463/465 for both Smad1 and Smad5) as well as Smad2/3 (Ser-465/467 for Smad2 and Ser-423/425 for Smad3) phosphorylation in each of the cell lines we studied: LX2, PSC, and MEF cells (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Smad protein phosphorylation by TGF-β1 stimulation in LX2, PSC, and MEF cells. LX2, PSC, and MEF cells were serum-starved overnight, then treated with different concentrations of TGF-β1 for 45 min. Antibodies against p-Smad1/5 (Ser-463/465), p-Smad2 (Ser-465/467), and p-Smad3 (Ser-423/425) were used. Both Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 were phosphorylated by TGF-β1 stimulation in all of the cells. An asterisk (*) indicates the nonspecific band.

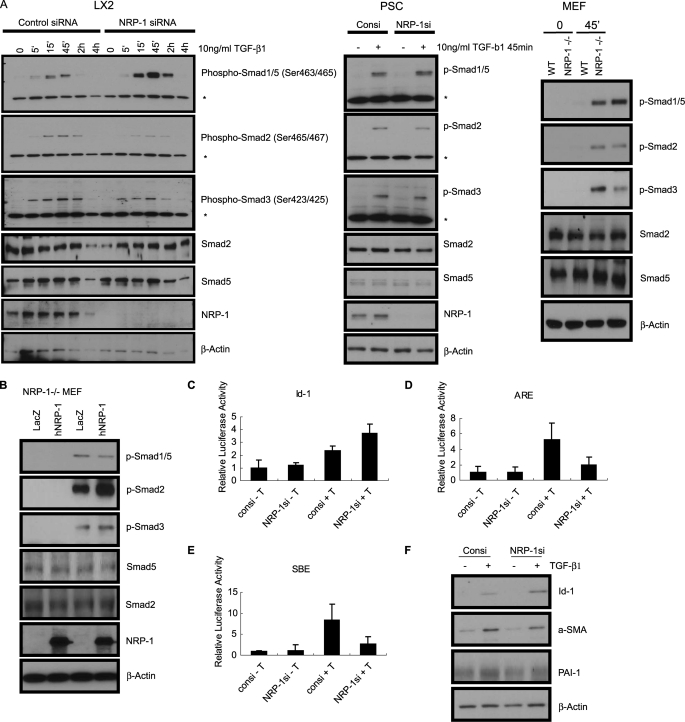

Based on the finding that NRP-1 binds TGF-β1, we hypothesized that ablation of NRP-1 could globally reduce Smad activation. Surprisingly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of NRP-1 in LX2 and PSC, and NRP-1 knock-out (NRP-1−/−) in MEF resulted in the enhanced phosphorylation of Smad1/5, while phosphorylation of Smad2/3 was impaired (Fig. 2A). NRP-1 overexpression in the NRP-1−/− MEF reversed the Smad phosphorylation responses in the present of TGF-β, as suppression of Smad1/5 phosphorylation and elevation of Smad2/3 phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Consistent with these results, knockdown of NRP-1 enhanced Id-1-Luc promoter (a Smad1 reporter that contains BMP binding elements (20)) activity and down-regulated activin response elements (ARE-Luc, a Smad2/4-specific reporter). Smad-binding elements (SBE-Luc), a Smad3 responsive reporter (21), was also down-regulated as a result of siRNA-mediated NRP-1 knockdown (Fig. 2, C–E). The Id-1 protein level was also enhanced after NRP-1 knockdown. Levels of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which were Smad2/3 response genes, were less responsive to TGF-β stimulation after NRP-1 knockdown (Fig. 2F).

FIGURE 2.

The effects of eliminating or overexpressing NRP-1 on Smad protein phosphorylation and the Smad target gene expression. A, eliminating NRP-1 up-regulated Smad1/5 phosphorylation and down-regulated Smad2/3 phosphorylation. NRP-1 was knocked down by siRNA in LX2 and PSC. For MEF cells, wt MEF, and NRP-1−/− MEF cells were used. All the cells were serum-starved overnight, and then treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for the indicated time. An asterisk (*) indicates the nonspecific band. B, overexpress NRP-1 in NRP-1−/− MEF cells down-regulated Smad1/5 phosphorylation and up-regulated Smad2/3 phosphorylation. NRP-1−/− MEF cells were infected with NRP-1 encoding retrovirus. LacZ retrovirus was used as control. After 36 h, cells were serum-starved overnight, and then treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for the indicated time. C–E, effect of knocking down NRP-1 on the Smad proteins transcriptional activity in the cells measured by the luciferase promoter assay. 5 × 103/well LX2 cells were plated into a 96-well plate transfected with NRP-1 siRNA for 24–30 h, then serum-starved overnight. The cells were then transfected with the corresponding luciferase promoter plasmids together with pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid as the internal control. One hour after the transfection, TGF-β1 was added to the corresponding well to the final concentration of 10 ng/ml. Firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were performed. C, Luc-Id-1 promoter. D, Luc-ARE, co-transfected with FAST. E, Luc-SBE. F, knocking down NRP-1 affected the Smad protein responding gene expression. Cells were transfected with NRP-1 siRNA for 24–30 h in the complete medium, then serum-starved overnight. 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 was added to the cells for 24 h. In response to TGF-β1 stimulation, Id-1 protein (the Smad1-responding gene) expression was more highly up-regulated in NRP-1 knocked down cells than in control cells stimulated with TGF-β1. In response to TGF-β1 stimulation, α-SMA and PAI-1 protein (the Smad3-responding gene) expression was more highly down-regulated in NRP-1 knocked down cells than in control cells stimulated with TGF-β1.

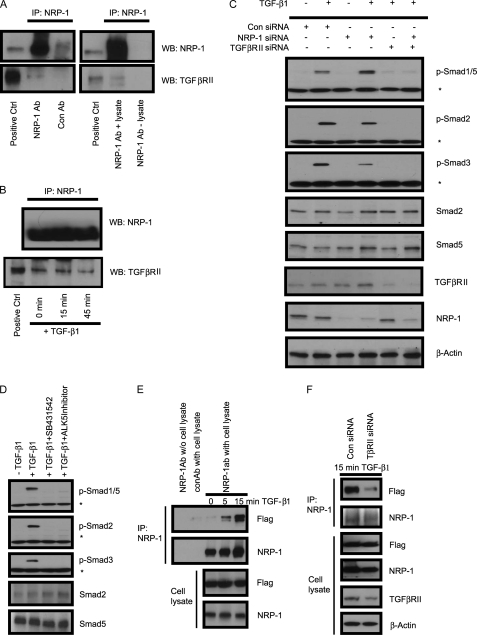

NRP-1 Associates with TGF-βRII

NRP-1 is known for the absence of any kinase domain, thus it cannot phosphorylate the Smad proteins directly. We investigated whether NRP-1 can interact with TGF-βRII as a co-receptor. Endogenous NRP-1 was co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous TGF-βRII (Fig. 3A) in LX2 cells, and TGF-β treatment did not increase the association between NRP-1 and TGF-βRII (Fig. 3B). Knockdown of TGF-βRII with siRNA completely blocked TGF-β-mediated Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 phosphorylation, and the regulating role of NRP-1 also eliminated (Fig. 3C), indicating that NRP-1 functions through TGF-βRII-regulated Smad protein phosphorylation.

FIGURE 3.

NRP-1 interacted with TGF-β receptors. A, NRP-1 bound to TGF-βRII. LX2 cells grown in the complete medium were made for cell lysate, and immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-NRP-1 antibody and Western blot for TGF-βRII. Control antibody with cell lysate and NRP-1 antibody without cell lysate were used as negative controls. B, TGF-β1 stimulation did not increase the association between NRP-1 and TGF-βRII. LX2 cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 0, 15, and 45 min. The cell lysate was made, and immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-NRP-1 antibody and Western blot for TGF-βRII. C, siRNA knocked down TGF-βRII eliminated the effect of NRP-1 on Smad protein phosphorylation. LX2 cells were transfected with control, NRP-1, and TGF-βRII siRNA alone or combined, as indicated in the figure. 24–30 h later, cells were serum-starved overnight. 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 was added to the indicated plates for 45 min, and the cell lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis. An asterisk (*) indicates the nonspecific band. D, TGF-βRI (ALK5) inhibitors eliminated both Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 protein phosphorylation on TGF-β1 stimulation. LX2 cells were serum-starved overnight. TGF-βRI inhibitors SB431542 (10 μm) and ALK5 Inhibitor (10 μm) were added to the cells 30 min before TGF-β1 stimulation. An asterisk (*) indicates the nonspecific band. E, NRP-1 associated with TGF-βRI (ALK5) by TGF-β1 stimulation. 293T cells were transfected with NRP-1 and Flag-ALK5-expressing plasmids. Cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 0, 5, and 15 min. The cell lysate was made, and immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-NRP-1 antibody and Western blot for Flag tag. F, knockdown TGF-βRII eliminated the association between NRP-1 and TGF-βRI (ALK5) in the present of TGF-β stimulation. 293T cells were transfected with TGF-βRII siRNA, and the following experiments were preformed as described in panel E.

NRP-1 may also directly regulate TGF-βRI to modulate the Smad protein phosphorylation. Smad1/5 phosphorylation was thought to occur exclusively during BMP signaling and TGF-β signaling in endothelial cells. However, recent studies indicate that TGF-β can stimulate both Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 in epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and tumor cells in a TGF-βRII-, ALK5-, and ALK2/3-dependent manner (14–16). Consistent with previous reports, we found that TGF-β can stimulate Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 phosphorylation through TGF-βRII in LX2 cells. Furthermore, the pharmacological TGF-β inhibitors SB431542 (which inhibits ALK4/5/7, but does not affect ALK1/2/3/6), and an ALK5 inhibitor (22) completely blocks Smad2/3 as well as Smad1/5 phosphorylation (Fig. 3D), indicated that the Smad2/3 and Smad1/5 phosphorylation is ALK5-dependent. Because of specificity limitations of commercially available ALK5 antibodies, we performed co-immunoprecipitation of ALK5 and NRP-1 using exogenous expression of both Flag-ALK-5 and NRP-1 in 293T cells. Our results demonstrate that NRP-1 associates with ALK-5 upon TGF-β stimulation in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3E). Knockdown the endogenous TGF-βRII in 293T cells by siRNA eliminated this association, indicating that the association between NRP-1 and ALK-5 was mediated by TGF-βRII (Fig. 3F).

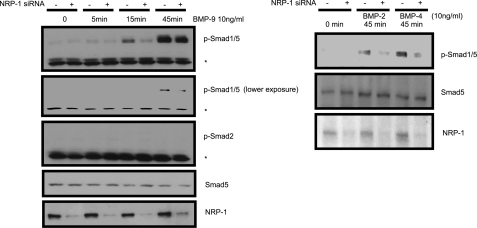

Knocking Down NRP-1 Impaired BMPs-induced Smad1/5 Phosphorylation

The TGF-β family member BMP, through BMP receptor combinations (ALK-1, 2, 3, and 6 as a type I receptor, BMPRII as a type II receptor), has been shown to activate the Smad proteins, specifically, Smad1, 5, and 8 (8). Because β-glycan and endoglin also regulate BMP signaling (23, 24), we hypothesized that NRP-1 may also influence BMP signaling. Indeed, knocking down NRP-1 impaired BMP-9, BMP-2, and BMP-4-induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation (Fig. 4). These results indicate that NRP-1 can also regulate signaling of the other TGF-β superfamily of proteins in addition to TGF-β.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of NRP-1 on BMPs signaling. LX2 cells were transfected with control and NRP-1 siRNA, as indicated in the figure. 24–30 h later, cells were serum-starved overnight. 10 ng/ml BMP9 was added to the indicated plates for 0, 5, 15, and 45 min, and cell lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis. For BMP2 and BMP4, only the 45 min time point was preformed. BMPs induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation was decreased by NRP-1 knockdown. An asterisk (*) indicates the nonspecific band.

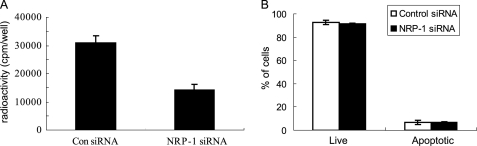

NRP-1 Knockdown Reduces Cell Proliferation and Leads to a Quiescent Phenotype

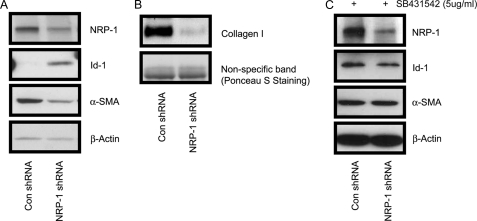

We addressed the cellular effects of blocking NRP-1 expression and observed that NRP-1 knockdown significantly decreased the proliferation of LX2 cells (Fig. 5A). Further, we investigated whether this reduction was caused by induction of apoptosis as we observed previously in endothelial cells that lacked NRP-1 expression (25). As demonstrated in Fig. 5B, NRP-1 knockdown did not cause cell apoptosis. Lentiviral NRP-1 shRNA was used to stably knockdown NRP-1 (>7days), and levels of active and quiescent stellate cell markers, α-SMA and Id-1, were examined. As shown in Fig. 6A, α-SMA was down-regulated and Id-1 was up-regulated in cells expressing NRP-1 shRNA as compared with that of controls. Given the in vitro cell culture conditions, LX2 cells are in a proliferative and active stage. The down-regulated α-SMA and up-regulated Id-1 suggest that the cells were reversed to a relatively quiescent phenotype. Also, collagen I production, which is expressed by the active fibroblasts was decreased after NRP-1 knockdown (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these results indicate that the cells were in a less activated stage, which could be due to the accumulation effect of the stimulation of a small amount of TGF-β in the culture medium. Indeed, in the present of TGF-β signaling inhibitor SB431542 (5 μg/ml), Id-1 and α-SMA protein levels didn't change after stable knockdown NRP-1 (7 days). Moreover, we noticed that, after knockdown of NRP-1, the cells exhibited the quiescent phenotypes in the first several passages and were gradually lost during culture (cell proliferation, Id-1, and α-SMA protein levels became the same as those of the control cells), even the NRP-1 knockdown was properly maintained by the shRNA (data not shown), which might be explained by the compensatory effects of the other signaling as the cells are prone to be activated in the in vitro culture system.

FIGURE 5.

Cells were less proliferative after silencing NRP-1. A, reduced cell proliferation capacity of NRP-1-silenced cells. LX2 cells were transfected with control and NRP-1 siRNA for 2 days, and cell proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. B, eliminating NRP-1 did not cause cell apoptosis. LX2 cells were transfected with control and NRP-1 siRNA for 2 days, and cell apoptosis was determined by annexin-FITC/PI assay.

FIGURE 6.

Cells acquired the quiescent phenotype after long-term silencing of NRP-1 by shRNA. A, increased expression of Id-1 protein, and reduced α-SMA protein in the NRP-1 shRNA LX2 cells compared with the control shRNA cells. B, collagen I protein was down-regulated in the NRP-1 shRNA LX2 cells compared with the control shRNA cells. The Ponceau S staining was used as the loading control. C, Id-1 and α-SMA protein levels did not change during long-term silencing of NRP-1 by shRNA in the present of 5 μm SB431542.

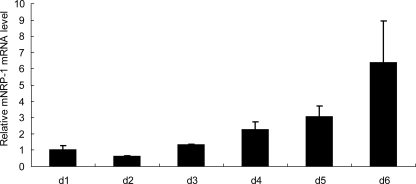

During Culture Activation, NRP-1 Was Up-regulated

Last, we correlated culture activation of HSC with NRP-1 expression with the idea that NRP-1 expression may positively correlate with myofibroblastic activation in vitro. Primary HSC undergo myofibroblastic activation in vitro upon extended culture and this culture-induced activation in vitro is a good model to mimic fibroblast activation in vivo. Mouse HSCs were isolated by the collagenase/Percoll density gradient centrifugation method (26), and cells were collected for RNA each day after culture. NRP-1 level change was determined by semi-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The results show that NRP-1 mRNA levels were gradually up-regulated during the culture (Fig. 7). Mouse HSCs were confirmed by α-SMA immunofluorescence staining (supplemental Fig. S2A), and the dramatically increased α-SMA level determined by semiquantitative real-time PCR during the culture activation confirmed that the cells were activated from the quiescent stage (supplemental Fig. S2B).

FIGURE 7.

The NRP-1 level was up-regulated during the culture activation of mouse HSC, which were isolated from mouse liver using the collagenase/Percoll density gradient centrifugation method. Cells were plated in the complete medium, and total RNA from cells was isolated every day. NRP-1 mRNA was measured by semi-quantitative real-time PCR.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that NRP-1, like β-glycan and endoglin, can regulate TGF-β signaling by interacting with TGF-βRII. These proteins have similar structures: a short cytoplasmic C-terminal tail containing a PDZ binding domain that binds to GAIP-interacting protein, C terminus (GIPC). NRP-1 and TβRIII are expressed in almost all kinds of cells, but levels vary. In addition to its role in neural and vascular development, NRP-1 is overexpressed in cancers and correlates with cancer progression and poor prognosis (4, 27, 28). Correspondingly, TβRIII expression was down-regulated in most cancer types (29). Although NRP-1 and TβRIII are dysregulated in malignancies, mutated forms of the proteins have not been found in tumors.

TGF-β was thought to act exclusively through TβRII and TβRI (ALK5) receptor complexes, as well as intracellular Smad2/Smad3, to mediate the signaling. In endothelial cells, which specifically express ALK-1, it was shown that TGF-β, through ALK1 active Smad1/5/8, regulates cell proliferation and migration (21). Recently, TGF-β was found to activate Smad1/5 in normal and cancerous epithelial cells and fibroblasts (14–16), and all of the results indicated that TGF-β-induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation depends on ALK5. Moreover, BMP type I receptors (ALK1/2/3/6) also participated in TGF-β-induced phosphorylation of Smad1/5 (14, 16). These results indicated that TGF-β, like other TGF-β family proteins, acts through multiple possible receptor combinations and regulates the complicated TGF-β signaling. While most cells express several TβRIs, it is possible that phosphorylation of Smad proteins is activated by different homodimeric TβRIs or a heterodimeric TβRI on TGF-β binding.

Knockdown TβRII blocks Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 signaling, and the regulatory role of NRP-1 also was inhibited. This, together with the results that NRP-1 and TβRII co-immunoprecipitation, indicates that NRP-1 regulates TGF-β signaling through TβRII. The impairment of BMPS signaling after knockdown NRP-1 also suggests that NRP-1, like β-glycan and endoglin, plays a role in BMP signaling, likely through the regulation of BMPRII. These findings also point out the complexity of TGF-β signaling initiation on the cell membrane. Given the cell-type specific expression patterns of TGF-β superfamily receptors, our observations regarding the novel role of NRP-1 in fibroblasts reveals an intriguing area of new investigation.

Physiologically, TGF-β signaling maintains tissue homeostasis; in pathogenesis, the deregulation of TGF-β signaling causes fibrosis, tumorigenesis, and metastasis. TGF-β plays an important role in fibrotic diseases in most organs (30), as well as stromal cell activation in tumor tissue. TGF-β has a dual role in the control of fibroblast activation. On one hand, it activates Smad1/5, which controls Id-1, a functional protein that can maintain a quiescent state and be a marker for quiescent stromal cells; on the other hand, it activates Smad2/3, which induces α-SMA expression, an active stromal cell/myofibroblast marker. Id-1 is abundantly exressed in quiescent stellate cells and diminished during activation (31, 32). Id-1−/− mice were susceptible to bleomycin-induced lung injury and fibrosis, and fibroblasts from Id-1−/− mice showed enhanced responses to TGF-β stimulation (33). Also, Id-1 up-regulation was an early event in the fibroblast after TGF-β stimulation. Id-1, a known Smad1 response gene, was up-regulated by phospho-Smad1 and can be suppressed by the Smad3/4 response gene ATF3 (34). Hence, Id-1 induced by TGF-β may act as a negative regulator to inhibit fibrosis progression. While Smad2/3 is known for inducing α-SMA expression, Smad3 also induces ATF-3 expression. ATF-3, together with Smad3/4, inhibits Id-1 expression and overcomes the quiescent effect of Id-1. Furthermore, Smad3−/− mice were resistant to TGF-β-mediated pulmonary fibrosis (35). These findings suggest that the functions of Smad1/5/8 and Smad2/3 may counteract each other, and the fibrotic process is involved in gaining of Smad2/3 signaling whereas diminishing of Smad1/5/8 signaling. It has been shown that during fibroblast activation, the expression of TβRI, TβRII, and TβRIII were dysregulated (36, 37). It is possible that up-regulation of NRP-1, as well as the TGF-β receptors, induces activation of the stellate cell by modulating TGF-β signaling.

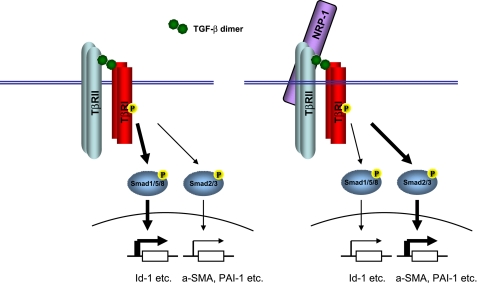

Here, we demonstrated that NRP-1 is a co-receptor of TGF-β and that it regulates the TGF-β canonical signaling in the Smad proteins phosphorylation. Interestingly, in the stromal/fibroblast cell, knocking down NRP-1 up-regulates TGF-β-induced Smad1/5 phosphorylation and down-regulates Smad/2/3 phosphorylation. The Id-1 protein, which is transcriptionally controlled by phospho-Smad1/5, is a major protein in maintaining the quiescent state of fibroblasts. Phospho-Smad2/3 controls α-SMA expression, a marker of fibroblasts activation. Thus, NRP-1 controls two aspects of TGF-β signaling: down-regulating of the Smad1/5 signaling which inhibits fibrosis progression and up-regulating of the Smad2/3 signaling, which promotes fibrosis; both reinforce fibrosis. During the activation, the up-regulated NRP-1 shifts the TGF-β signaling from Smad1/5/8 to Smad2/3, from maintenance of the quiescent state to activation of the cells (Fig. 8). NRP-1 might also regulate TGF-β non-Smad signaling, such as collagen production (17). Like endoglin, NRP-1 expression is also increased during fibroblast activation. According to our results, NRP-1 up-regulation worsens the fibrosis, but endoglin up-regulation seems to attenuate fibrosis (38–40). The mechanism of NRP-1 up-regulation during fibroblasts activation is unclear. NRP-1 also functions as a cell adhesion molecular (41) and it is possible that NRP-1 is up-regulated by the similar mechanisms as the integrins during the cell activation. TGF-β also controls NRP-1 and TβRIII expression. Endoglin is up-regulated by TGF-β (40), while β-glycan and NRP-1 is down-regulated by TGF-β (42, 43) (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 8.

The schematic illustration of NRP-1 function in regulating TGF-β signaling. TGF-β induced both Smad1/5/8 and Smad2/3 phosphorylation in the fibroblast cells. Without NRP-1 (left panel), Smad1/5/8 is more phosphorylated and Smad2/3 less phosphorylated, and the corresponding gene expression controlled by the Smad proteins (e.g. Smad1/Id-1, Smad3/a-SMA, PAI-1) caused the cell to enter a less activated state (more quiescent). With NRP-1 (right panel), Smad1/5/8 is less phosphorylated, and Smad2/3 is more phosphorylated, and the corresponding gene expression controlled by the Smad proteins caused the cell to enter a more activated state (less quiescent).

The mechanism through which NRP-1 controls the Smad1/5 and Smad2/3 phosphorylation counterbalance is still largely unknown. It is possible that NRP-1 binds TβRII, presents TGF-β more favorably to ALK4/5/7 than ALK1/2/3/6, or the existence of NRP-1 in the TGF-β receptor complex changes the TβRI's conformation, mediating phosphorylation of Smad2/3 rather than Smad1/5/8. Furthermore, NRP-1 may recruit other proteins to the complex.

The cell growth arrest observed upon knockdown of NRP-1 is likely not TGF-β-dependent. In the present of SB431542 (which inhibited the TGF-β-Smad signaling), knocking down NRP-1 still induces cell growth arrest (supplemental Fig. S4). It has been previously shown that NRP-1 has TGF-β-independent functions such acting as a semaphorin 3 (SEMA3) and VEGF co-receptor (1, 2, 29), mediating cell adhesion (41) and binding galectin-1 (44), forming receptor complexes with platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) and modulating PDGF signaling (45). It also can regulate endothelial cell survival independent of VEGF receptors (25). Finally, NRP-1 is known to promote vascular and neural development, immune responses (46), and cancer progression. TGF-β is also well known for participating in these processes. Consequently, the role of NRP-1 in the regulation of TGF-β signaling in these processes needs to be defined in the future.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA78383, HL072178, and HL70567. This work was also supported by a Mayo Clinic Pancreatic Cancer SPORE Pilot grant, a grant from the American Cancer Society as well as the Bruce and Martha Atwater Foundation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Methods.

- VPF

- vascular permeability factor

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic proteins

- NRP

- neuropilin

- PSC

- pancreatic tumor stromal cells

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

REFERENCES

- 1.He Z., Tessier-Lavigne M. (1997) Cell 90, 739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soker S., Takashima S., Miao H. Q., Neufeld G., Klagsbrun M. (1998) Cell 92, 735–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glinka Y., Prud'homme G. J. (2008) J. Leukoc. Biol. 84, 302–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagri A., Tessier-Lavigne M., Watts R. J. (2009) Clin. Cancer. Res. 15, 1860–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson U., Izumi H., Souchelnytskyi S., Itoh S., Grimsby S., Engström U., Heldin C. H., Funa K., ten Dijke P. (1998) FEBS Lett. 434, 83–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh S., ten Dijke P. (2007) Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 19, 176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang J. S., Liu C., Derynck R. (2009) Trends Cell. Biol. 19, 385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massagué J., Gomis R. R. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 2811–2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massagué J., Seoane J., Wotton D. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 2783–2810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massagué J. (2008) Cell 134, 215–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Lagna G., Hata A. (2008) Nature 454, 56–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Descargues P., Sil A. K., Sano Y., Korchynskyi O., Han G., Owens P., Wang X. J., Karin M. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2487–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He W., Dorn D. C., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Moore M. A., Massagué J. (2006) Cell 125, 929–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly A. C., Randall R. A., Hill C. S. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6889–6902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu I. M., Schilling S. H., Knouse K. A., Choy L., Derynck R., Wang X. F. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 88–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrighton K. H., Lin X., Yu P. B., Feng X. H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9755–9763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao S., Yaqoob U., Das A., Shergill U., Jagavelu K., Huebert R. C., Routray C., Abdelmoneim S., Vasdev M., Leof E., Charlton M., Watts R. J., Mukhopadhyay D., Shah V. H. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 2379–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao Y., Wang L., Nandy D., Zhang Y., Basu A., Radisky D., Mukhopadhyay D. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 8667–8672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L., Zeng H., Wang P., Soker S., Mukhopadhyay D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48848–48860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korchynskyi O., ten Dijke P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4883–4891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goumans M. J., Valdimarsdottir G., Itoh S., Rosendahl A., Sideras P., ten Dijke P. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 1743–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gellibert F., Woolven J., Fouchet M. H., Mathews N., Goodland H., Lovegrove V., Laroze A., Nguyen V. L., Sautet S., Wang R., Janson C., Smith W., Krysa G., Boullay V., De Gouville A. C., Huet S., Hartley D. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47, 4494–4506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkbride K. C., Townsend T. A., Bruinsma M. W., Barnett J. V., Blobe G. C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7628–7637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scherner O., Meurer S. K., Tihaa L., Gressner A. M., Weiskirchen R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13934–13943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L., Dutta S. K., Kojima T., Xu X., Khosravi-Far R., Ekker S. C., Mukhopadhyay D. (2007) PLoS One. 2, e1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vrochides D., Papanikolaou V., Pertoft H., Antoniades A. A., Heldin P. (1996) Hepatology 23, 1650–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis L. M. (2006) Mol. Cancer. Ther. 5, 1099–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klagsbrun M., Takashima S., Mamluk R. (2002) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 515, 33–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatza C. E., Blobe G. C. (2008) Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. http://AtlasGeneticsOncology.org/Genes/TGFBR3ID42S41ch1p33.html

- 30.Branton M. H., Kopp J. B. (1999) Microbes Infect. 1, 1349–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann D. A., Smart D. E. (2002) Gut 50, 891–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent K. J., Jones E., Arthur M. J., Smart D. E., Trim J., Wright M. C., Mann D. A. (2001) Gut 49, 713–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin L., Zhou Z., Zheng L., Alber S., Watkins S., Ray P., Kaminski N., Zhang Y., Morse D. (2008) Am. J. Pathol. 173, 337–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang Y., Chen C. R., Massagué J. (2003) Mol. Cell. 11, 915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonniaud P., Kolb M., Galt T., Robertson J., Robbins C., Stampfli M., Lavery C., Margetts P. J., Roberts A. B., Gauldie J. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 2099–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roulot D., Sevcsik A. M., Coste T., Strosberg A. D., Marullo S. (1999) Hepatology 29, 1730–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman S. L., Yamasaki G., Wong L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 10551–10558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Barbero A., Obreo J., Alvarez-Munoz P., Pandiella A., Bernabéu C., López-Novoa J. M. (2006) Cell. Physiol Biochem. 18, 135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo B., Slevin M., Li C., Parameshwar S., Liu D., Kumar P., Bernabeu C., Kumar S. (2004) Anticancer Res. 24, 1337–1345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Obreo J., Díez-Marques L., Lamas S., Düwell A., Eleno N., Bernabéu C., Pandiella A., López-Novoa J. M., Rodríguez-Barbero A. (2004) Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 14, 301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu M., Murakami Y., Suto F., Fujisawa H. (2000) J. Cell. Biol. 148, 1283–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hempel N., How T., Cooper S. J., Green T. R., Dong M., Copland J. A., Wood C. G., Blobe G. C. (2008) Carcinogenesis 29, 905–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schramek H., Sarközi R., Lauterberg C., Kronbichler A., Pirklbauer M., Albrecht R., Noppert S. J., Perco P., Rudnicki M., Strutz F. M., Mayer G. (2009) Lab. Invest. 89, 1304–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh S. H., Ying N. W., Wu M. H., Chiang W. F., Hsu C. L., Wong T. Y., Jin Y. T., Hong T. M., Chen Y. L. (2008) Oncogene 27, 3746–3753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ball S. G., Bayley C., Shuttleworth C. A., Kielty C. M. (2010) Biochem. J. 427, 29–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romeo P. H., Lemarchandel V., Tordjman R. (2002) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 515, 49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.