Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between prenatal secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, preterm birth and immediate neonatal outcomes by measuring maternal hair nicotine.

Design

Cross-sectional, observational design.

Setting

A metropolitan Kentucky birthing center.

Participants

Two hundred ten (210) mother-baby couplets

Methods

Nicotine in maternal hair was used as the biomarker for prenatal SHS exposure collected within 48 hours of birth. Smoking status was confirmed by urine cotinine analysis.

Results

Smoking status (nonsmoking, passive smoking, and smoking) strongly correlated with low, medium, and high hair nicotine tertiles (rho = .74; p < .001). Women exposed to prenatal SHS were more at risk for preterm birth (OR = 2.3; 95% CI: .96–5.96), and their infants were more likely to have immediate newborn complications (OR = 2.4; 95% CI 1.09–5.33) than non-exposed women. Infants of passive smoking mothers were at increased risk for respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (OR = 4.9; 95% CI 1.45–10.5) and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (OR= 6.5; CI: 1.29 to 9.7) when compared to infants of smoking mothers (OR 3.9; 95% CI: 1.61–14.9; OR 3.5; 95% CI: 2.09–20.4; respectively). Passive smokers and/or women with hair nicotine levels greater than .35 ng/ml were more likely to deliver earlier (1 week); give birth to infants weighing less (decrease of 200 to 300 grams); and deliver shorter infants (decrease of 1.1 to 1.7 cm).

Conclusions

Prenatal SHS exposure places women at greater risk for preterm birth and their newborns are more likely to have RDS, NICU admissions and immediate newborn complications.

Keywords: Preterm birth, Secondhand smoke exposure, Hair nicotine biomarkers, Smoking and pregnancy

Introduction

The rate of preterm birth (PTB) in the United States has dramatically increased by 21% from 1990 to 2006 (Martin et al., 2007). Preterm birth is a complex public health problem. The phenomenon of PTB has been described as a “cluster” of problems with a set of overlapping factors of influence (Behrman & Butler, 2007). Causes may include individual-level behavioral and psychological factors, socio-demographic and neighbor-hood characteristics, environmental exposure, medical conditions, infertility treatments, and biological factors. Many of the survivors suffer life-long complications, and in 2005 the cost of PTB was estimated at $26.2 billion (Behrman & Bultler, 2007).

Preterm birth can be categorized as medically indicated (when pregnancy is interrupted at preterm gestations for maternal or fetal indications) and spontaneous (onset of labor before or after membrane rupture at preterm gestations). More than one-half of PTBs due to medical indications are on the basis of conditions associated with ischemic placental disease including preeclampsia, fetal distress, small-for-gestational-age (SGA) and placental abruption (Ananth & Vintzileos, 2006). With the exception of preeclampsia, maternal smoking is associated with each of these etiologies and is a frequent risk factor for PTB. Despite the well known association of maternal smoking with PTB, less is known about the effects of SHS on pregnancy outcomes. To date, few studies have documented adverse on neonatal and pregnancy outcomes in nonsmoking women. Furthermore, of the studies that report on adverse outcomes, few have used long-term biomarkers of SHS exposure.

Exposure of pregnant women to SHS is pervasive. In 2006, a report from the U.S. Surgeon General reported there is no safe level of SHS exposure; and in fact, SHS exposure causes premature death in infants and adults (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006b). Due to the potential significant health implications, this study examines the relationship between prenatal secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure, preterm birth and immediate neonatal outcomes using measurements of maternal hair nicotine. The specific aim of the study was to examine the relationship between maternal hair nicotine concentrations and four newborn outcomes: gestational age at birth; birthweight; birthlength; and immediate newborn complications. We hypothesized that 1) nonsmoking women with prenatal exposure to SHS will have the same incidence of PTB compared to nonsmoking, nonexposed pregnant women; and 2) infants of nonsmoking women exposed to prenatal SHS exposure will have similar birthweights, birthlengths and the same incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission within the first 24 hours of life compared to infants of nonsmoking, nonexposed women.

Review of the Literature

Direct and Indirect maternal-fetal biomarkers of nicotine exposure

A mother’s decision to quit smoking during pregnancy is often motivated by her concern for the health of her infant. However, high postpartum relapse rates suggest that mothers are less aware of the adverse effects of secondhand smoke (SHS) on their infants (Bottorff, Johnson, Irwin, & Ratner, 2000; Fingerhut, Kleinman, & Kendrick, 1990). Because pregnant women often under report or misrepresent their smoking status (Bottorff et al., 2000; Dukic, Niessner, Pickett, Benowitz, & Wakschlag, 2009) and/or extent of SHS exposure (DeLorenze, Kharrazi, Kaufman, Eskenazi, & Bernert, 2002), biomarker confirmation is justified. Biomarkers of maternal SHS exposure during pregnancy can be detected in both the mother and the fetus (Eliopoulos et al., 1994; Jacqz-Aigrain et al., 2002; Klein & Koren, 1999; Nafstad et al., 1998). Biomarker validation (Webb, Boyd, Messina, & Windsor, 2003), or a combined assessment of biomarker and self-report measures (Dukic et al., 2009) are recommended methods to confirm prenatal smoking and SHS exposure status.

Maternal and fetal biomarkers occur from direct maternal consumption of nicotine and from inhalation of SHS. Biomarkers for quantifying maternal smoking and SHS exposure during pregnancy include, but are not limited to salivary cotinine (McBride et al., 1999; Van't Hof, Wall, Dowler, & Stark, 2000), serum cotinine (DeLorenze et al., 2002; Kaufman, Kharrazi, Delorenze, Eskenazi, & Bernert, 2002; Kharrazi, DeLorenze, Kaufman, Eskenazi, & Bernert, 2004; Peacock et al., 1998), expired carbon monoxide (Hajek et al., 2001; Johnson, Ratner, Bottorff, Hall, & Dahinten, 2000), urine cotinine (Pichini et al., 2000; Webb et al., 2003), hair cotinine (Klein & Koren, 1999), and hair nicotine (Jaakkola, Jaakkola, & Zahlsen, 2001; Pichini et al., 2003). Fetal exposure to nicotine occurs after absorbed nicotine and its metabolite, cotinine, diffuse through the placenta (Sastry, Chance, Hemontolor, & Goddijn-Wessel, 1998). Nicotine/cotinine is then deposited in many fetal/placental fluids and tissues, including hair (Eliopoulos et al., 1994; Jacqz-Aigrain et al., 2002; Klein & Koren, 1999).

Analysis of aternal hair nicotine captures a longer range of SHS exposure than urine or serum cotinine and expired CO and offers a more valid measure of SHS exposure than cotinine analysis from biological fluids (Al-Delaimy, Crane, & Woodward, 2002). Although research comparing maternal self-report or acute measures of SHS exposure to birth outcomes is well documented; little has been explored using long-term exposure measures. Hair nicotine is one of the few biomarkers that measure long-term exposure to secondhand smoke in nonsmoking women (Jaakkola et al., 2001; Klein & Koren, 1999; Pichini et al., 2003). Because human hair grows approximately 1–2 cm per month, a one cm segment of hair represents exposure for the previous 1–2 months (Zahlsen & Nilsen, 1994); compared to cotinine which has a half-life of approximately 20 hours in human biological fluids (Benowitz, 1999).

Nicotine in maternal hair is the biomarker most strongly associated with parental reports of SHS exposure (Sorensen, Bisgaard, Stage, & Loft, 2007). Examination of cotinine/nicotine hair analysis in mother-baby couplets is not new; however, few have explored the relationship to preterm birth and neonatal characteristics. Of the couplet research using hair nicotine, half of the studies found moderate to strong correlations between mother-infant nicotine levels (Eliopoulos et al., 1994; Klein & Koren, 1999). Others found no correlation between maternal and infant hair nicotine (Jacqz-Aigrain et al., 2002; Nafstad et al., 1998). Furthermore, of the studies conducting prenatal hair nicotine analysis, few examined the relationship between level of exposure and neonatal outcomes.

Prenatal SHS exposure and neonatal outcomes

Without reservation, maternal-child research has repeatedly demonstrated associations between direct maternal consumption of tobacco products and adverse birth outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006). However, much less is known about how prenatal consumption of SHS in nonsmoking women effects birth outcomes. Using maternal hair nicotine analysis (2 cm segment of hair reflecting two months of exposure in third trimester), only one study linked SHS in nonsmoking women to preterm birth and/or neonatal outcomes. Jaakkola et al. (2001) reported an increase risk of preterm [(OR) = 6.12; 95% CI, 1.31–28.7]; low birth weight [OR was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.96–1.17)] and small-for-gestational-age [1.04 (95% CI, 0.92–1.19)].

Studies reporting on neonatal outcomes in nonsmoking women have generally used shorter periods of prenatal exposure (1–2 days) or based findings on self-report. Jedrychowski et al. (2004; 2009) assessed the effect of prenatal airborne particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure in the second trimester on selected birth outcomes (gestational age, weight, length, and head circumference at birth) and found all were negatively affected by the exposure. Three studies further demonstrated the association between domestic prenatal SHS exposure and lowered mean infant birth weights by 36, 79 and 137 grams, respectively (Goel, Radotra, Singh, Aggarwal, & Dua, 2004; Hegaard, Kjaergaard, Moller, Wachmann, & Ottesen, 2006; Ward, Lewis, & Coleman, 2007). Goel et al. (2004) and Fantuzzi et al. (2007) reported prenatal exposure to ETS contributed to increased risk for preterm birth and severe SGA. Furthermore, a meta analysis examining the relationship between birth outcomes and SHS exposure in nonsmoking women concluded maternal passive smoking in early and mid/late pregnancy led to an increased risk for small-for –gestational age (SGA) infants. (Liu, Chen, He, Ding, & Ling, 2009)

Methods

Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional observational study design was used to investigate the relationship between the level of maternal hair nicotine to preterm birth and newborn outcomes. Permission to conduct the study was obtained through the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) board. After consent was obtained, trained research assistants administered a health questionnaire, and collected maternal urine and mother-baby hair samples. Participants were offered a choice of a $25 stipend or $25-equivalent of diapers to participate.

In a metropolitan Kentucky birthing center, 210 postpartum mothers (within three days of birth) consented to participate. To be eligible for study inclusion, women had to be ≥18 years with no reported prenatal use of drugs of abuse in their medical records. With an effective sample size of 200 mothers and an alpha level of .05, the power of Pearson’s product moment correlation to detect a significant association as small as .2 was calculated to be at least 80%. Quota sampling was used to ensure a representative distribution of mothers who were smokers, nonsmokers/passive exposed, and nonsmokers/nonexposed during pregnancy.

Data Collection and Measures

Mothers were identified via the Labor and Birth daily census report and approached about participating in postpartum Birthing Center rooms. After obtaining written consent, mothers were asked to complete a questionnaire. Following completion of the questionnaire, trained research assistants collected urine and hair samples.

Smoking validation and SHS assessment

Previously reported high deception rates in self-report of smoking during pregnancy resulted in validation of smoking status using NicAlert, a commercial urine assay, and based on cut-off limits of urine cotinine (NicAlert, 2007). Nonsmokers were defined by urine cotinine ≤ 99 ng/ml (level 00–02). Current smokers were defined by urine cotinine ≥ 100 ng/ml (level 03–06). NicAlert cutoffs for smoking validation are consistent with previous reported urine cotinine ranges (Higgins et al., 2007).

Participants completed a prenatal health and smoking history questionnaire (average completion time: 22 minutes) based on recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): Smoking Cessation During Pregnancy: A Clinician's Guide to Helping Pregnant Women Quit Smoking and previous published hair sampling studies (Jaakkola & Jaakkola, 1997); (Hahn et al., 2006; Okoli, Hall, Rayens, & Hahn, 2007). Recommended questions included: number of day or hours exposed to smoking in the home, work or vehicle in the past 7 days; number of persons smoking in the home; and information on cosmetic perms, straighteners, bleaching and hair dye. A woman was classified as a self-reported smoker if she responded “yes” to the question, “Have you smoked a cigarette, even a puff, in the past 7 days.” Smoking mothers were asked to classify their daily smoking consumption, within the past 30 days, based on the following 10 categories: <1 cigarette, 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, 21–25, 31–35, 36–40, and > 40.

The questionnaire also assessed SHS exposure. SHS exposure is defined as the contact of passive smoke “to the eyes, the epithelium of the nose, mouth, and throat, and the lining of the airways and alveoli” (Jaakkola & Jaakkola, 1997). Average daily number of cigarettes smoked for each family member and visitor (within the past week) was calculated based on the following five categories: 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, >20 (Al-Delaimy et al., 2002). Furthermore, number of exposure sources was calculated by adding home, car/vehicle and work exposures (0–3)(Okoli et al., 2007). If the participant did not quantify any exposures (days or hours) to any of the exposure questions (home, car/vehicle, work) they were classified as nonsmoking, nonexposed (NS). Classification of SHS exposure (in confirmed nonsmokers) was based on self-report. If a participant answered “yes” or quantified exposure (days or hours) to any of the smoking exposure questions, they were classified as “nonsmoking, passive-exposed” (PS) (Hahn et al., 2006; Okoli et al., 2007).

Maternal hair nicotine collection and analysis

Research assistants completed a two-hour workshop on urine and hair nicotine collection and analysis. Training was conducted by an expert in hair nicotine collection (Hahn et al., 2006). Two trained RA’s collected all urine and hair samples. Collection of maternal hair involved cutting a proximal segment of hair from the posterior vertex of the scalp. The hair segment (approximately 20–25 strands) was cut as close as possible to the scalp and placed in a paper envelope and taped. For analysis, duplicate groups of 1–2 cm lengths were cut. Because human hair grows approximately 1 cm per month, this length of hair reflects exposure for the previous 1–2 months (Zahlsen & Nilsen, 1994). Hair samples were stored in the paper envelope until being mailed to Wellington Hospital, Wellington, New Zealand for analysis. Hair samples can be stored without deterioration for at least 5 years (Zahlsen & Nilsen, 1994). All hair samples were mailed and analyzed within six months of collection. Each hair sample was cleaned thoroughly to remove any nicotine on the outside of the hair prior to analysis. Nicotine was extracted from the hair and measured using the method of Mahoney and Al-Delaimy (2001). Nicotine was quantified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection (ECD). The limit of detection was 0.05 ng/mg hair, and the more relevant parameter for our analysis, the limit of quantitation was about 0.3 ng/mg hair. More detail regarding maternal hair nicotine analysis can be found in a previous publication (Ashford et al., 2010)

Preterm Delivery and Neonatal Outcomes

After delivery, birth and neonatal outcomes from mother and infant medical records were collected by the primary investigator within the first three days of birth. Infants were categorized preterm or term and as having any documented complications with the first 24 hours of birth, including NICU admission, RDS, or SGA. Preterm birth included infants that are born at less than 37 completed weeks of gestation (ACOG). SGA infants were defined as those with a birthweight less than or equal to the 10th percentile (Wilcox & Skjaerven, 1992).

During data analysis infant birthweight, birthlength, and raw hair nicotine data were log-transformed to normalize the distributions. For nicotine data, geometric means (GM), i.e., the anti-logs of the means of the log-transformed data, were used to convert the means of the log-transformed values back to the original scale. Univariate analyses were used to summarize demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the participants. Non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney for two-group comparisons; and Kruskall-Wallis for more than two groups) were used to assess the differences between level of maternal hair nicotine and infant outcome variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho) was used to correlate smoking status and maternal hair nicotine tertiles. Multiple linear regression was used to determine predictors of birthweight and birthlength using maternal hair nicotine while adjusting for potential confounders.

Since an increase in specific medical risk factors during pregnancy can have adverse health effects on the fetus, an indicator variable for prenatal complications (i.e., preeclampsia, preterm labor, history of preterm birth and diabetes) was included as a covariate in the regression analyses. Logistic regression was used to determine which demographic and smoking status variables predicted specific birth outcomes, while controlling for potential confounders (i.e., maternal age; education; infant gender; ethnicity; gestational age; and prenatal complications). The coefficient of variation (R2) was determined to estimate the variability in birth outcomes predicted by the other independent variables. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was used to determine how well the logistic model fit the data. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0; and alpha level of .05 was used throughout.

Results

After medical record review, 42 mothers were excluded due to prenatal drug abuse and age. Refusal rate was low (<10%), with nearly all women who refused to participate indicating an unexpected maternal and/or infant complication as the reason to decline. General smoking characteristics of the 210 recruited mothers consisted of: 53 (25%) smokers and 157 (75%) nonsmokers. Of the nonsmokers, 66(31%) reported being exposed to SHS and 91(69%) were nonsmokers/nonexposed during pregnancy. The final sample consisted of 208 women. Two mothers were unable to complete the study due to early discharge. A multiethnic sample was recruited of: Caucasian (57%); Hispanic (25%); African American (15%); Asian (1%); and multi-ethnicity (1%). All mothers were between the ages of 18–40, with a mean age of 26 (SD = 5.4) years; 42% were educated beyond high school; and 55% had a family income of $30,000 or less per year (see Table 1). On average, infants were born at 38 weeks gestation; weighed 3159 grams; were 49.9 cm in length; and had 1, 5 minutes Apgar scores of 8. There were more male infants (57%) than females (43%); and 43 (20%) infants were born premature.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Smoking Status

| Smoker |

Passive/ NonExposed |

NonSmoker/ NonExposed |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity/Race (n=210) | n=91 (%) | n=53 (%) | n=66 (%) | |||

| White | 45 (21.4) | 41 (19.5) | 33 (15.7) | |||

| African American | 8 (3.8) | 10 (4.8) | 14 (6.7) | |||

| Hispanic | 35 (16.7) | 0 | 18 (8.6) | |||

| Asian | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Marital Status (n=209) | ||||||

| Single | 25 (12) | 34 (16.3) | 35 (16.7) | |||

| Married | 64 (30.6) | 15 (7.2) | 26 (12.4) | |||

| Separated | 2 (1) | 3 (1.4) | 5 (2.4) | |||

| Highest Grade Completed (n=209) | ||||||

| Less than High School | 22 (11.1) | 13 (6.2) | 23 (11.0) | |||

| High School/GED | 17 (8.1) | 25 (12) | 20 (9.6) | |||

| Some College and above | 14 (6.7) | 27 (12.9) | 48 (23) | |||

| Household Income (n=172) | ||||||

| Less than $20K | 34 (19.8) | 32 (18.6) | 24 (14) | |||

| $20K – $39.9K | 6 (3.5) | 10 (5.8) | 24 (14) | |||

| $40K and above | 2 (1.2) | 10 (5.8) | 30 (17.4) | |||

| Other Characteristics | SD | SD | SD | |||

| Age (years) | 24.8 | 5.11 | 24.3 | 5.15 | 27.2 | 5.37 |

| Adults smoking inside > | ||||||

| 1mo | 2.4 | 1.95 | 1.2 | 1.35 | 0.1 | 0.31 |

| Total Hours Passive | ||||||

| Smoke | ||||||

| (hrs calculated per week) | 79.8 | 53.22 | 45 | 40.98 | 0 | 0 |

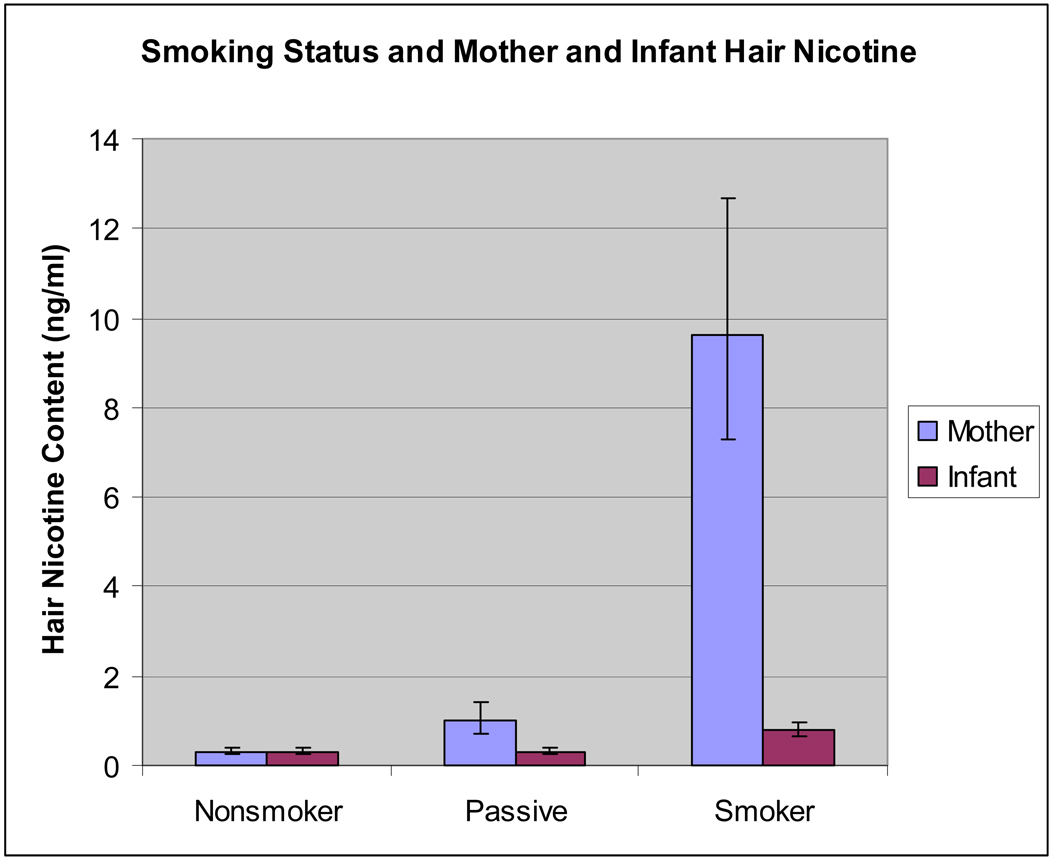

Maternal hair nicotine was significantly different among the three groups: nonsmoking, non-exposed (NS); nonsmoking, passive exposed (PS); and smoking (Kruskal-Wallis; X df=2 = 116.67; p < .0001). Figure 1 depicts the relationship between smoking classification and maternal and infant hair nicotine levels. There was a strong correlation between urine cotinine and self-reported smoking status (rho = .88; p < .0001). Correlations between smoking variables and mother-baby hair nicotine are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Comparisons between smoking status and mother and infant hair nicotine

aNote: mother hair significant among all smoking groups (p < .0001)

bNote: infant hair significant between passive and smoker groups (p < .0001)

Table 2.

Self-reported smoking variables and mother-baby hair nicotine

| Self-reported smoking variables |

Log-transformed hair nicotine levels (ng/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Maternal hair | Infant hair | |

| Smoking status | .74* | .39* |

| Number of cigarettes/day | .68* | .47* |

| Number of adults in home smoking | .66* | .27* |

| SHS home exposure (hours/week) | .65* | .02 |

| SHS home and car/vehicle (hours/week) | .63* | .27* |

| Number of exposure sources | .58* | .19* |

| SHS car/vehicle exposure (hours/week) | .46* | .07 |

p = 0.01 level

Maternal hair nicotine was selected to measure differences in maternal and infant birth outcomes for the following reasons: 1) there was a moderate and significant correlation between mother-baby couplet hair nicotine (rho = .46; p < .0001); 2) maternal hair nicotine samples were more strongly correlated with all of the self-reported smoking behaviors than were the infant samples; and 3) all measured smoking behaviors were significantly correlated with maternal hair nicotine samples. The strongest relationship was between maternal hair nicotine and the ordinal smoking status variable (NS, PS, and smoking) described in Table 3. For variance analysis, maternal hair nicotine was subdivided into tertiles; low hair nicotine (LHN); medium hair nicotine (MHN); and high hair nicotine (HHN). Since the maternal hair nicotine tertiles were significantly associated with self-reported smoking and SHS exposure status, maternal hair nicotine was used as the measure for comparisons between prenatal SHS exposure and neonatal outcomes. Maternal hair nicotine tertiles were defined by level of hair nicotine: 1) having less than or equal to .34 ng/ml of nicotine (LHN); 2) having .35 to 2.08 ng/ml of nicotine (MHN); and 3) having greater than or equal to 2.09 ng/ml of hair nicotine (HHN) (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Associations between selected birth outcomes and maternal hair nicotine by tertile

| Maternal Hair Nicotine Levels (ng/ml)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Outcomes | Low (≤.3) |

Medium (.31 to 2.09) |

High (≥ 2.1 ) |

||

| n (%) | 68 | 71 | 69 | ||

| Birthweight** | 207 | 3431.5 ± 557 |

3125.9 ± 768 |

2924.0 ± 857 |

|

| Mean Difference | (−306 grams) |

(−508 grams) |

|||

| Birthlength** | 206 | 51.2 ± 3.1 | 49.8 ± 4.2 | 48.7 ± 5.3 | |

| Mean Difference | (−1.4 cm) | (−2.5 cm) | |||

| Gestational Age* | 208 | 38.5 ± 2.4 | 37.6 ± 3.4 | 37.0 ± 3.7 | |

| Mean Difference | (−1 week) | (−1.5 weeks) | |||

| Infant Complication < 24 hours** | 74 | 17(25%) | 22(31%) | 35(51%) | |

| Preterm Birth*+ | 43 | 7(10%) | 16(23%) | 19(28%) | |

| Respiratory Distress** | 47 | 6(9%) | 14(20%) | 27(39%) | |

| NICU Admission** | 45 | 3(4%) | 15(21%) | 27(39%) | |

| SGA** | 11 | - | 4(6%) | 7(10%) | |

significant at the .05 level among tertiles

significant at the .01 level among tertiles

nanograms/milliliter

Table 4.

Maternal hair nicotine tertiles and smoking groups (ng/ml)

| Classification | Maternal hair nicotine | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median/ Tertile range |

Geometric mean | |

| NS | 91 | .30 | .32 |

| LMH tertile | 68 | ≤ .34 | .21 |

| PS | 66 | .74 | .99 |

| MHN tertile | 71 | .35 – 2.09 | .83 |

| Smoking | 53 | 9.81 | 9.61 |

| HHN tertile | 69 | ≥ 2.1 | 14.09 |

Overall, geometric means and median ranges in maternal hair nicotine content (LHN, MHN, HHN) mirrored the values in the ordinal smoking groups (NS, PS, smoking). See Table 4 for comparisons between maternal hair nicotine tertiles and smoking classifications. As women smoke, or are exposed to SHS during pregnancy, hair nicotine levels increase. There were significant differences in maternal hair nicotine content and smoking classifications (Kruskal-Wallis; Xdf=2 = 116.67; p <.0001). Smoking mothers’ median hair nicotine content was more than 30 times higher than that of NS mothers, and 14 times higher than PS mothers. Differences in maternal hair nicotine between NS and PS women was also significant but less profound when compared to smoking women (Xdf=2 = 36.22; p < .0001). Mothers exposed to prenatal SHS had three times higher hair nicotine levels than NS mothers.

For the four logistic regression models, maternal age, education, ethnicity, gestational age (except the PTB model) and prenatal complications were controlled. An indicator variable for prenatal complications (i.e., preeclampsia, preterm labor, and diabetes) was included as a covariate in the regression analyses. Participants were categorized as having prenatal complications if any complications were documented in the mother’s medical record. For each dependant variable, maternal hair nicotine level and smoking status were entered separately to ascertain which smoking-related variable best predicted maternal and infant outcomes (see Table 5). The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was used to determine if the model fit the data. In all logistic regressions, Model 1 included level of maternal hair nicotine; while Model 2 included the smoking status variables. When examining the odds ratios (ORs), preterm birth was significantly influenced by prenatal passive smoke exposure. The final logistic model for preterm birth was significant: [B = 1.35; SE =.171; Exp(B) =3.68; p = .0001]. Both smoking and PS women were nearly 2 ½ times more likely to experience preterm birth than NS women. There were many similarities among the regression models for newborn outcomes. In all three models, maternal hair nicotine, smoking, and passive smoking were significant predictors. Infants of PS women were more likely to experience adverse newborn outcomes than infants of NS women (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Logistic regression models for birth outcomes

| Dependent Variables |

Independent Variables |

β |

Std err |

χ2a |

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premature Birthb | ||||||

| Model 1 | Maternal HN | 0.08 | 0.13 | 5.94 | 1.1 | .84 – 1.40 |

| Model 2 | Smoker | 0.87 | 0.47 | 4.72 | 2.4 | .80 – 6.71 |

| Passive | 0.84 | 0.54 | 2.3 | .96 – 5.96 | ||

| Immediate Newbornc | ||||||

| Complications | ||||||

| Model 1 | Maternal HN | 0.23* | 0.12 | 7.69 | 1.26 | 1.00 – 1.58 |

| Model 2 | Smoker | 1.02* | 0.47 | 1.58 | 2.8 | 1.10 – 7.02 |

| Passive | 0.88* | 0.4 | 2.4 | 1.09 – 5.33 | ||

| RDSc | ||||||

| Model 1 | Maternal HN | 0.32* | 0.13 | 10.5 | 1.4 | 1.06 – 1.78 |

| Model 2 | Smoker | 1.36** | 0.51 | 2.52 | 3.9 | 1.61 – 14.9 |

| Passive | 1.59** | 0.57 | 4.89 | 1.45 – 10.5 | ||

| NICU Admission c | ||||||

| Model 1 | Maternal HN | 0.43** | 14 | 1.53 | 1.16 – 2.02 | |

| Model 2 | Smoker | 1.27** | 0.51 | 11.9 | 3.54 | 2.09 – 20.4 |

| Passive | 1.88** | 0.58 | 6.53 | 1.29 – 9.70 | ||

Note: Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 : P

Note: Controlling age, education, ethnicity, gestational age, and prenatal conditions

Note: Controlling age, education, ethnicity, prenatal complications

p < .05

p < .01

Preterm birth and neonatal outcomes (birthweight; birthlength; and immediate newborn complications) were significantly different among maternal hair nicotine tertiles. A significant relationship existed between preterm birth and hair nicotine tertiles (Kruskal-Wallis; X2(df=2) = 24.1; p = .012) and between the NS and PS groups (Wilcoxon = 4675; p = .05). Approximately 80% of mothers who delivered preterm infants were in the smoking and SHS-exposed groups compared to only 17% in the nonexposed group.

Birthweight and birthlength were both significant among tertiles and between the LHN and MHN groups (Kruskal-Wallis; X2(df=2) = 19.44; p <.0001; Kruskal-Wallis; X2(df=2) = 11.01; p = .004; respectively). Birthweight and birthlength progressively declined with increasing levels of hair nicotine (see Table 4). A significant relationship existed between gestational age and hair nicotine tertiles (Kruskal-Wallis; X2(df=2) = 24.1; p = .012), but not between LHN and MHN groups. An infant’s risk of having complications within the first 24 hours of life was significantly different among maternal hair nicotine tertiles (Kruskal-Wallis; X2(df=2) = 10.8; p = .004). Of the 74 infants who had complications, over 75% were born from smoking or SHS-exposed women.

In the linear regression model, maternal age, education, ethnicity, maternal hair nicotine, gestational age, infant gender, and prenatal complications predicted nearly 75% of the variance in infant birthweight and birthlength [F (9, 185) = 56.34; R2 =. 73; p < .0001; F (9, 184) = 57.29; R2 =. 74; p < .0001; respectively]. Multicollinearity assessments for the smoking variable did not suggest any confounding with other control variables in the models. In both models, the log-transformed raw maternal hair nicotine levels were more predictive of birthweight and birthlength than smoking status variables or hair nicotine tertiles; while gestational age at birth was the strongest predictor.

Discussion

Whether a woman smokes during pregnancy or is exposed to SHS, biomarkers of exposure can be detected in both the mother and the fetus (Eliopoulos et al., 1994; Jacqz-Aigrain et al., 2002; Klein & Koren, 1999; Nafstad et al., 1998). Biomarker validation rather than self-report is recommended to confirm smoking and SHS exposure (Webb et al., 2003). Hair nicotine is one of the few biomarkers that measure chronic exposure to SHS in nonsmoking women (Jaakkola et al., 2001; Klein & Koren, 1999; Pichini et al., 2003) and is a more valid measure of long-term SHS exposure than cotinine analysis from biological fluids (Al-Delaimy et al., 2002).

Because smoking during pregnancy is not socially desirable, many women misrepresent their smoking status or level of smoking; thus validating the need for biomarker confirmation. Limited research exists on the relationship between prenatal SHS exposure and its effect of prematurity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006a). In our study, smoking, either directly or indirectly through the inhalation of SHS was associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Women exposed to prenatal SHS exposure were 2–3 times more likely to have a preterm birth than those who do not smoke and are not exposed, and equally as likely to have a preterm birth compared to mothers who smoke during pregnancy. Higher level of maternal hair nicotine also reflected greater risk for preterm birth and adverse neonatal outcomes (first 24 hours of life). These results support previous studies reporting an increased risk of preterm birth in women exposed to prenatal SHS (Ward et al., 2007; Webb et al., 2003; Windham, Hopkins, Fenster, & Swan, 2000).

Because few studies have examined the relationship between prenatal SHS exposure and NICU admission; our strong finding of a significant increase in NICU admission in women exposed to SHS in the prenatal period is noteworthy. These women were 2–4 times more likely to experience complications than nonsmoking mothers. The most reported complications in the infant medical records were RDS and SGA. Fantuzzi et al. (2008) reported adverse newborn outcomes, specifically severe SGA, in nonsmoking women exposed to prenatal SHS; however, in a recent systematic review on maternal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in nonsmoking women, there was an increased risk of low birthweight (below 2500 grams) but no clear impact on risk for SGA (Leonardi-Bee, Smyth, Britton, & Coleman, 2008). Although only 11 infants in our study were diagnosed as SGA, all were from smoking or SHS-exposed women. The review by Leonardi-Bee also reported a reduction of 33 grams or more in birthweight (Leonardi-Bee et al., 2008) in passively exposed women; comparable to our findings in which there was a birthweight reduction of 306 grams and birthlength reduction of 1.4 cm. Additionally, Tsui et al. (2008) reported a reduction in birthweight and birthlength in infants (with high DNA damage) of nonsmoking women exposed to environmental tobacco smoke.

Regardless of the method nicotine enters maternal circulation, diffusion is the mechanism responsible for transport of nicotine across the placenta (Lambers & Clark, 1996). Because nicotine has a small molecular structure and is highly lipid soluble, it easily diffuses across the cell membrane (Sastry et al., 1998). Nicotine/cotinine is commonly deposited in human amniotic fluid, fetal hair, meconium, placental tissue and cord blood (Chan, Caprara, Blanchette, Klein, & Koren, 2004; Jauniaux, Gulbis, Acharya, Thiry, & Rodeck, 1999).

We found maternal hair to be a reliable and efficient biomarker for measuring direct maternal nicotine consumption and prenatal SHS exposure in women who do not smoke (Ashford et al., 2010). Although mother-baby hair samples were moderately correlated; maternal hair nicotine was a more precise biomarker of self-reported prenatal SHS exposure than infant hair (Ashford et al., 2010). Cutting hair was a noninvasive, straightforward method to collect biomarkers of chronic exposure to prenatal SHS in both the mother and infant. Research using more short-term measures of exposure may potentially underestimate the effect of SHS exposure on preterm birth and neonatal outcomes.

There were limitations to this study. Because quota sampling is a nonrandom sampling method, sampling error cannot be calculated. Although a sample size of 210 provided adequate power, logistic regression for SGA was not permitted due to the limited number of SGA infants (n = 11). Although the overall refusal rate was low, this limited subsample could be explained by an increased refusal rate of mothers of infants admitted to the NICU (44%) compared to mothers of healthy term infants (35%). Due to cost of laboratory cotinine analysis, validation of smoking status was based on a commercial urine assay, NicAlert (Nyomox Pharmaceutical Corporation, 2007). However, in another study, NicAlert measurement correlated well with more complex laboratory tests using HPLC used in the CDC laboratory (Bernert, Harmon, Sosnoff, & McGuffey, 2005).

It is clear that there is limited research of the health effects of prenatal SHS on pregnancy/neonatal outcomes when compared to research on the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy. A larger proportion of women stop smoking during pregnancy than at other times in their lives. Up to 40% of women in the United States who smoke before pregnancy stop before their first prenatal appointment (CDC, 2004). However, two-thirds of women who stop smoking during pregnancy relapse within one year of delivery (CDC, 2004.) Possibly, women may perceive less of a health risk from SHS exposure to their infants. Mc Bride, Emmons, & Lipkus (2003) suggested that pregnancy may be a "teachable moment" for smoking cessation due to an increased perception of risk for poor pregnancy outcomes which evokes strong emotional responses. With more knowledge about the adverse health effects of prenatal exposure to SHS, pregnant women may also choose to avoid exposure. Nurses and other health care practitioners should inquire about SHS exposure at a woman’s first prenatal appointment; provide education on the adverse maternal and infant health effects of SHS exposure; and encourage avoidance of SHS during and after pregnancy. Future research needs to be directed toward 1) qualitative studies to further understand a mother’s profound desire to quit smoking during pregnancy, yet remain in SHS environments; 2) additional evidence on the interaction of prenatal SHS exposure (using long-term biomarkers) on neonatal and child health; and 3) examination of the effects of smoke-free policy or smoke-free homes on preterm birth in high risk populations.

Acknowledgement

Funded by a University of Kentucky Faculty Research Grant; a USPHS grant supporting the University of Kentucky General Clinical Research Center #M01RR02602; and Grant # K12DA14040 from the Office of Women’s Health Research and the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institute of Health (NIH). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. The authors thank Graeme Mahoney, HSO, Specialist Biochemistry Laboratory, Wellington Hospital, Wellington, New Zealand, for analyzing nicotine in hair.

Biography

Kristin B. Ashford, ARNP, PhD, is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY and has been awarded a three year NIH post-doctoral Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) fellowship.

Ellen Hahn, PhD, RN is alumni professor and director of the Tobacco Policy Research Program, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY.

Lynne Hall, DrPH is associate dean for research and scholarship and a Marcia A. Drake Professor of Nursing Science at University of Kentucky, College of Nursing, Lexington, KY.

Mary Kay Rayens, PhD is associate professor of nursing and public health, University of Kentucky, College of Nursing, Lexington, KY.

Melody Noland, PhD is a professor and department chair of kinesiology and health promotion, University of Kentucky, College of Education, Lexington, KY.

James E. Ferguson, MD, MBA, (AU: need position title) University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Footnotes

Callouts

1. Prenatal second hand smoke exposure increases an infant’s risk for admission to the neonatal intensive care unit and respiratory distress syndrome.

2: Whether a woman smokes during pregnancy or is exposed to second hand smoke, biomarkers of exposure can be detected in the mother and the fetus.

3: Participants who were exposed to smoking experienced adverse perinatal outcomes more frequently than those who were not.

References

- Al-Delaimy WK, Crane J, Woodward A. Is the hair nicotine level a more accurate biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure than urine cotinine? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56(1):66–71. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Maternal-fetal conditions necessitating a medical intervention resulting in preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;195(6):1557–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.021. doi:S0002-9378(06)00660-0[pii]10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford KB, Hahn E, Hall L, Rayens MK, Noland M, Collins R. Measuring prenatal secondhand smoke exposure in mother-baby couplets. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12(2):127–135. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp185. doi: ntp185 [pii] 10.1093/ntr/ntp185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman RE, Butler AS. Preterm birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. Washington D.C: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. Biomarkers of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1999;107 Suppl 2:349–355. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert JT, Harmon TL, Sosnoff CS, McGuffey JE. Use of cotinine immunoassay test strips for preclassifying urine samples from smokers and nonsmokers prior to analysis by LC-MS-MS. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2005;29(8):814–818. doi: 10.1093/jat/29.8.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Irwin LG, Ratner PA. Narratives of smoking relapse: the stories of postpartum women. Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23(2):126–134. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(200004)23:2<126::aid-nur5>3.0.co;2-2. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(200004)23:2<126::AID-NUR5>3.0.CO;2-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006 [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking during pregnancy—United States, 1990–2002. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(39):911–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D, Caprara D, Blanchette P, Klein J, Koren G. Recent developments in meconium and hair testing methods for the confirmation of gestational exposures to alcohol and tobacco smoke. Clinical Biochemistry. 2004;37(6):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.01.010. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.01.010 S0009912004000323 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pregnant women: the association between self-report and serum cotinine. Environmental Research. 2002;90(1):21–32. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4380. doi: S0013935101943804 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukic VM, Niessner M, Pickett KE, Benowitz NL, Wakschlag LS. Calibrating self-reported measures of maternal smoking in pregnancy via bioassays using a Monte Carlo approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009;6(6):1744–1759. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6061744. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6061744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulos C, Klein J, Phan MK, Knie B, Greenwald M, Chitayat D, Koren G. Hair concentrations of nicotine and cotinine in women and their newborn infants. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(8):621–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi G, Aggazzotti G, Righi E, Facchinetti F, Bertucci E, Kanitz S, Sciacca S. Preterm delivery and exposure to active and passive smoking during pregnancy: a case-control study from Italy. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2007;21(3):194–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00815.x. doi: PPE815 [pii] 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzi G, Vaccaro V, Aggazzotti G, Righi E, Kanitz S, Barbone F, …Facchinietti F. Exposure to active and passive smoking during pregnancy and severe small for gestational age at term. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2008;21(9):643–647. doi: 10.1080/14767050802203744. doi: 903248196 [pii] 10.1080/14767050802203744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(5):541–544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel P, Radotra A, Singh I, Aggarwal A, Dua D. Effects of passive smoking on outcome in pregnancy. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2004;50(1):12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EJ, Rayens MK, York N, Okoli CT, Zhang M, Dignan M, Al-Delaimy WK. Effects of a smoke-free law on hair nicotine and respiratory symptoms of restaurant and bar workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006;48(9):906–913. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000215709.09305.01. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000215709.09305.01 00043764-200609000-00006 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, West R, Lee A, Foulds J, Owen L, Eiser J, Main N. Randomized controlled trial of a midwife-delivered brief smoking cessation intervention in pregnancy. Addiction. 2001;96(3):485–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96348511.x. doi: 10.1080/0965214002005446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegaard HK, Kjaergaard H, Moller LF, Wachmann H, Ottesen B. The effect of environmental tobacco smoke during pregnancy on birth weight. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85(6):675–681. doi: 10.1080/00016340600607032. doi: 743725785 [pii] 10.1080/00016340600607032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Mongeon JA, Solomon LJ, McHale L, Bernstein IM. Biochemical verification of smoking status in pregnant and recently postpartum women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15(1):58–66. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.58. doi: 2007-01684-005 [pii] 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola JJ, Jaakkola N, Zahlsen K. Fetal growth and length of gestation in relation to prenatal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke assessed by hair nicotine concentration. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2001;109(6):557–561. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109557. doi: sc271_5_1835 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola MS, Jaakkola JJ. Assessment of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. European Respiratory Journal. 1997;10(10):2384–2397. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacqz-Aigrain E, Zhang D, Maillard G, Luton D, Andre J, Oury JF. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and nicotine and cotinine concentrations in maternal and neonatal hair. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(8):909–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, Acharya G, Thiry P, Rodeck C. Maternal tobacco exposure and cotinine levels in fetal fluids in the first half of pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;93(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrychowski W, Bendkowska I, Flak E, Penar A, Jacek R, Kaim I, Perera FP. Estimated risk for altered fetal growth resulting from exposure to fine particles during pregnancy: an epidemiologic prospective cohort study in Poland. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112(14):1398–1402. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrychowski W, Perera F, Mroz E, Edwards S, Flak E, Bernert J, Musial A. Fetal exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke assessed by maternal self-reports and cord blood cotinine: prospective cohort study in Krakow. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13(3):415–423. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Ratner PA, Bottorff JL, Hall W, Dahinten S. Preventing smoking relapse in postpartum women. Nursing Research. 2000;49(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman FL, Kharrazi M, Delorenze GN, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Estimation of environmental tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy using a single question on household smokers versus serum cotinine. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2002;12(4):286–295. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharrazi M, DeLorenze GN, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Environmental tobacco smoke and pregnancy outcome. Epidemiology. 2004;15(6):660–670. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000142137.39619.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J, Koren G. Hair analysis--a biological marker for passive smoking in pregnancy and childhood. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 1999;18(4):279–282. doi: 10.1191/096032799678840048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers DS, Clark KE. The maternal and fetal physiologic effects of nicotine. Seminars in Perinatology. 1996;20(2):115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(96)80079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi-Bee J, Smyth A, Britton J, Coleman T. Environmental tobacco smoke and fetal health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2008;93(5):F351–F361. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.133553. doi: adc.2007.133553 [pii]10.1136/adc.2007.133553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Chen WQ, He YH, Ding P, Ling WH. A meta-analysis on the association between maternal passive smoking during pregnancy and small-for-gestational-age infants. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2009;30(1):68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney GN, Al-Delaimy W. Measurement of nicotine in hair by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Journal Of Chromatography B, Biomedical Sciences And Applications. 2001;753(2):179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00540-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2006. Vol. 57. Hyattsville, MD: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Curry SJ, Lando HA, Pirie PL, Grothaus LC, Nelson JC. Prevention of relapse in women who quit smoking during pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(5):706–711. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Education Research. 2003;18(2):156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafstad P, Fugelseth D, Qvigstad E, Zahlen K, Magnus P, Lindemann R. Nicotine concentration in the hair of nonsmoking mothers and size of offspring. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(1):120–124. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyomox Pharmaceutical Corporation. NicAlert: Expressing the results as cotinine concentration ranges. Hasbrouck Heights, NJ: Author; 2007 Retrieved from http://wwwnicalert.net/nicalert/er.html.

- Okoli CT, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Hahn EJ. Measuring tobacco smoke exposure among smoking and nonsmoking bar and restaurant workers. Biological Research for Nursing. 2007;9(1):81–89. doi: 10.1177/1099800407300852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock JL, Cook DG, Carey IM, Jarvis MJ, Bryant AE, Anderson HR, Bland JM. Maternal cotinine level during pregnancy and birthweight for gestational age. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;27(4):647–656. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichini S, Basagana XB, Pacifici R, Garcia O, Puig C, Vall O, Sunyer J. Cord serum cotinine as a biomarker of fetal exposure to cigarette smoke at the end of pregnancy. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2000;108(11):1079–1083. doi: 10.1289/ehp.001081079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichini S, Garcia-Algar O, Munoz L, Vall O, Pacifici R, Figueroa C, Sunyer J. Assessment of chronic exposure to cigarette smoke and its change during pregnancy by segmental analysis of maternal hair nicotine. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2003;13(2):144–151. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry BV, Chance MB, Hemontolor ME, Goddijn-Wessel TA. Formation and retention of cotinine during placental transfer of nicotine in human placental cotyledon. Pharmacology. 1998;57(2):104–116. doi: 10.1159/000028231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen M, Bisgaard H, Stage M, Loft S. Biomarkers of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in infants. Biomarkers: Biochemical Indicators Of Exposure, Response, And Susceptibility To Chemicals. 2007;12(1):38–46. doi: 10.1080/13547500600943148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui HC, Wu HD, Lin CJ, Wang RY, Chiu HT, Cheng YC, et al. Prenatal smoking exposure and neonatal DNA damage in relation to birth outcomes. Pediatric Research. 2008;64(2):131–134. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181799535. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181799535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2006a

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2006b

- Van't Hof SM, Wall MA, Dowler DW, Stark MJ. Randomised controlled trial of a postpartum relapse prevention intervention. Tobacco Control. 2000;9 Suppl 3:64–66. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Lewis S, Coleman T. Prevalence of maternal smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy and impact on birth weight: retrospective study using Millennium Cohort. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-81. doi: 1471-2458-7-81 [pii] 10.1186/1471-2458-7-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb DA, Boyd NR, Messina D, Windsor RA. The discrepancy between self-reported smoking status and urine continine levels among women enrolled in prenatal care at four publicly funded clinical sites. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2003;9(4):322–325. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R. Birth weight and perinatal mortality: the effect of gestational age. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(3):378–382. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windham GC, Hopkins B, Fenster L, Swan SH. Prenatal active or passive tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of preterm delivery or low birth weight. Epidemiology. 2000;11(4):427–433. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahlsen K, Nilsen OG. Nicotine in hair of smokers and non-smokers: sampling procedure and gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric analysis. Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1994;75(3–4):143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]