Abstract

AIM: To investigate the early metastasis-associated proteins in sentinel lymph node micrometastasis (SLNMM) of colorectal cancer (CRC) through comparative proteome.

METHODS: Hydrophobic protein samples were extracted from individual-matched normal lymph nodes (NLN) and SLNMM of CRC. Differentially expressed protein spots were detected by two-dimensional electrophoresis and image analysis, and subsequently identified by matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry and Western blotting, respectively.

RESULTS: Forty proteins were differentially expressed in NLN and SLNMM, and 4 metastasis-concerned proteins highly expressed in SLNMM were identified to be hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C and Annexin A1. Further immunohistochemistry staining of these four proteins showed their clinicopathological characteristics in lymph node metastasis of CRC.

CONCLUSION: Variations of hydrophobic protein expression in NLN and SLNMM of CRC and increased expression of hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C and Annexin A1 in SLNMM suggest a significantly elevated early CRC metastasis.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Micrometastasis, Proteomics, Sentinel lymph node

INTRODUCTION

At present, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. Its incidence in China has increased rapidly during the past few decades[2]. Since CRC metastasis has a great effect on the survival of its patients and selection of its treatment modalities, it is therefore important to understand the molecular basis of metastasis in order to develop better preventive and therapeutic procedures. CRC development is a multi-step process that spans 10-15 years, with different proteins involved in different steps[3], it is thus of great significance to find out the proteins involved in micrometastasis for early detection and treatment of CRC.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) provide the primary lymphatic drainage of a tumor, thus metastatic cancer cells first spread into the lymph nodes. It has been shown that the prognosis of CRC patients is related to sentinel lymph node micrometastasis (SLNMM)[4,5]. SLN techniques, such as SLN biopsy[6-8] and SLN mapping[9-11], have been used in diagnosis of CRC and can better stage CRC than standard HE analysis. Since SLN is the most intensively exposed to bioactive tumor cell products, it is important to know which proteins play a role in micrometastasis. Therefore, detection of differentially expressed proteins in SLNMM is of great significance in understanding the molecular mechanism underlying early CRC metastasis.

Comparative proteome techniques allow the characterization of global alterations in protein expression during cancer development and has been widely used in many kinds of tumors, including CRC[12]. Current studies on proteomics in CRC are mainly focused on comparison between primary CRC foci, normal tissue, and distant metastasis[13-16], or between different tumor cell lines[17,18], but the technology has not yet been used in comparison between SLNMM and normal lymph nodes (NLN). In this study, the technique was used to identify the differentially expressed proteins in SLNMM in order to find out the early metastasis-associated proteins in CRC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue sample collection

Forty-three cases of moderately differentiated colorectal adenocarcinoma (24 males and 19 females) at the age of 39-80 years (mean ± SD = 51.2 ± 12.6 years), who underwent operation from January 2007 to January 2008, were randomly collected from Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, China. Endoscopic ultrasonography was carried out 1 d before operation to identify the invasion extent and 0.1% isosulfan blue was injected circumferentially around the neoplasm to mark SLN[19].

A set of lymph nodes were collected during operation and stained with HE and cytokeratin-20 immunohistochemistry (CK-IHC) immediately by two experienced pathologists. Based on HE staining and CK-IHC, the lymph nodes were divided into NLN and SLNMM. All samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further analysis. All patients recruited in this study received neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy before surgery. Permission for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. All specimens were anonymous and handled according to the ethical and legal standards.

Protein sample preparation

Protein was extracted from 50 mg of frozen tissue by homogenization in lysis buffer containing 4% CHAPS, 2 mol/L thiourea, 7 mol/L urea, 2% NP-40, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mmol/L DTT, 5 mmol/L PMSF, 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, 2% pharmalyte, 1 mg/mL DNase I, 0.25 mg/mL RNase A, and 40 mmol/L tris-HCl, at pH 8.5, and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 40 000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was saved and stored at -70°C. Supernatants from 10 individual specimens corresponding to each group were pooled to minimize the individual variations, and the protein concentration in each mixed sample was measured with the bicinchoninic acid method using PBS as the standard.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and image analysis

Three hundred micrograms protein of each group was loaded onto a 240 mm linear IPG strip (pH3-10, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for first-dimensional isoelectric focusing. Protein separation in the second dimension SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was carried out on vertical systems, IPG strips were loaded and run on a 125 g/L acrylamide SDS-PAGE gel in electrode buffer (Tris 0.025 mol/L, glycine 0.192 mol/L, SDS 1 g/L, pH8.3). Electrophoresis was performed with a current of 30 mA/gel for 15 min, followed by 60 mA/gel for 4 h. Each sample was subjected to 2D gel electrophoresis three times to avoid procedural errors. After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with silver nitrate and scanned with an Imagescanner (Amersham Biosciences). The software of PD-Quest 7.3.1 (Bio-Rad) was employed for image analysis, including background abstraction, spot intensity calibration, spot detection, and matching.

Protein identification

Differential protein spots selected were excised from 2-DE gels and cut into small pieces, which were destained, reduced and digested with trypsin overnight. Tryptic digests were extracted and analyzed in a matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) (Bruker, Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). The resultant MS data were then screened against NCBInr and SWISS-PROT databases using the MASCOT search program (Matrix Science, London, UK; http://www.matrixscience.com). Protein identities were assigned if at least 4 peptide masses were matched within a maximum of 100 ppm error spread across the data set and the candidate agreed with the estimated pI and molecular weight from the 2-DE gel.

Western blotting

Tissue samples were lysed following the method for 2-DE described above. Aliquots of protein extracts (50 mg) were separated on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Subsequently, the protein was electrophoretically transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). After blocked with TBS-Tween 20 (TBST) containing 10% skim milk, the membranes were incubated with mouse monoclonal antibodies against mouse hnRNP A1 and tubulin β-2C, and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against mouse Annexin A1 and Ezrin for 1 h, respectively, followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted at 1:10 000 in TBST for 1 h. Finally, blots were developed with chemiluminescent reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). In order to equal protein loading, blots were re-stained using anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as a control.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized and rehydrated using xylene and a series of graded alcohol, respectively. Tissue sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxidase for 15 min at room temperature, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with anti-hnRNP A1 (1:50 Gmbh, Forckenbeckstr, Aachen, Germany), anti-tubulin β-2C (1:50 Saier Biotechnology Inc, Wuhan, China), anti-Annexin A1 (1:100 Saier Biotechnology Inc, Wuhan, China), and anti-Ezrin (1:50 Gmbh, Forckenbeckstr, Aachen, Germany) antibodies, respectively. Finally, the tissue sections were incubated with ready to use peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (MaiXin, Fuzhou, China), developed with diaminobenzidine as chromogen, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data were analyzed by Student’s t-test and χ2 test using SPSS 10.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

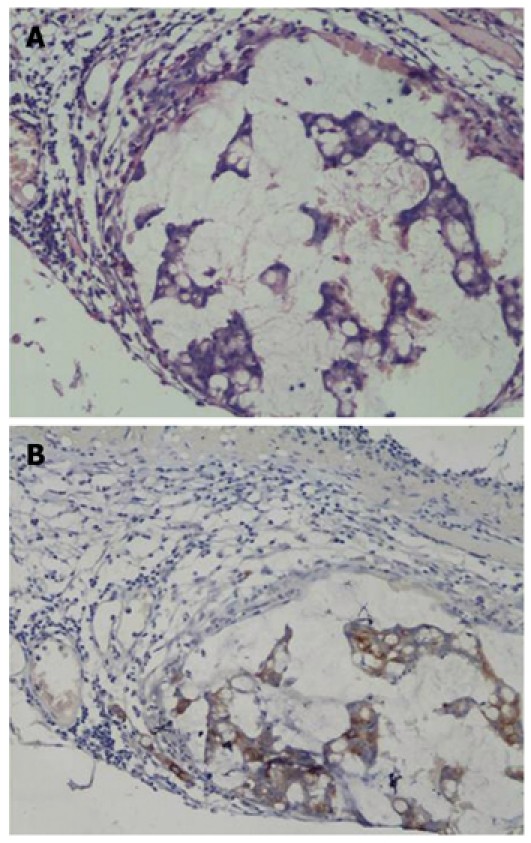

Harvesting and identification of SLNMM

A total of 62 NLN and 126 blue-stained lymph nodes from 43 patients were excised and processed. As a result, 37 and 54 blue-stained lymph nodes were considered to be SLNMM with HE staining (29.36%, Figure 1A) and CK-IHC (42.85%, Figure 1B), respectively, and at least one SLNMM was detected in each case.

Figure 1.

HE staining (A) and cytokeratin-20 immunohistochemistry (B) of sentinel lymph nodes (× 200).

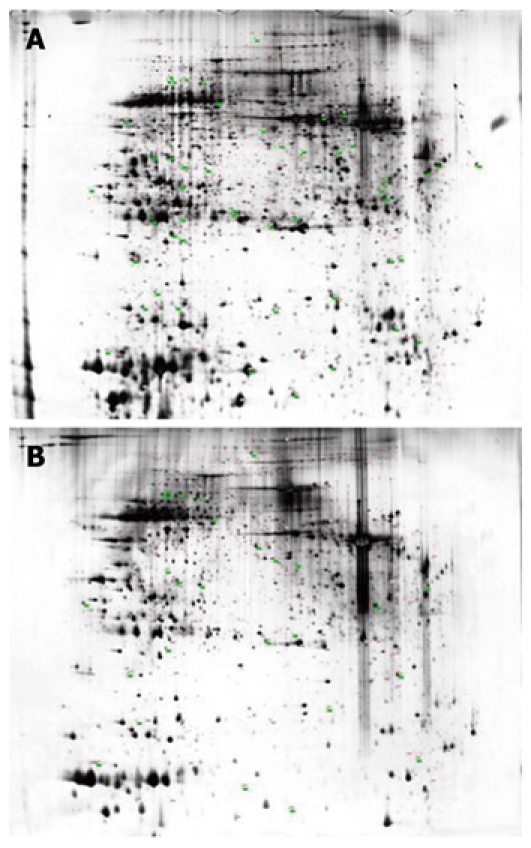

Differential expression of proteome in NLN and SLNMM

Sixty-three protein spots were differentially expressed in NLN and SLNMM (Figure 2). Among the 63 protein spots, some could not be identified with incomplete polypeptide fragments, and some were too low in abundance to obtain useful data. Finally, 40 protein entries were identified by MALDI-TOF-MS analyses (Table 1). The expression was up-regulated and down-regulated in 15 and 25 protein entries, respectively.

Figure 2.

Representative 2-DE maps of normal lymph nodes (A) and sentinel lymph node micrometastasis (B). The numbered spots represent differentially expressed proteins.

Table 1.

Identification of differentially expressed proteins in normal lymph nodes and sentinel lymph node micrometastasis of colorectal cancer

| Spot ID | International proteinindex accession No. | Protein | Score | Sequence coverage (%) | Mr/pI |

| Up | |||||

| 185 | IPI00307162 | VCL Isoform 2 of Vinculin | 98 | 11 | 124 292/5.50 |

| 482 | IPI00168698 | PDZD8 PDZ domain-containing protein 8 | 198 | 15 | 129 681/5.78 |

| 5151 | IPI00027834 | HNRNPL heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L isoform a | 119 | 17 | 64 720/8.46 |

| 501 | IPI00216952 | LMNA Isoform C of Lamin-A/C | 190 | 41 | 65 153/6.40 |

| 530 | IPI00289499 | ATIC Bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein PURH | 252 | 46 | 65 089/6.27 |

| 741 | IPI00021187 | RUVBL1 Isoform 1 of RuvB-like 1 | 133 | 39 | 50 538/6.02 |

| 1071 | IPI00027444 | SERPINB1 Leukocyte elastase inhibitor | 94 | 38 | 42 829/5.90 |

| 12661 | IPI00007752 | TUBB2C Tubulin β-2C chain | 134 | 30 | 50 255/4.79 |

| 1411 | IPI00103433 | TCP11 Isoform 1 of T-complex protein 11 homolog | 108 | 24 | 56 675/5.08 |

| 14491 | IPI00218918 | ANXA1 Annexin A1 | 196 | 50 | 38 918/6.57 |

| 1649 | IPI00554767 | CLIC1 18 kDa protein | 96 | 52 | 17 927/4.71 |

| 16501 | IPI00746388 | EZR Ezrin | 133 | 21 | 69 353/5.88 |

| 1967 | IPI00878282 | ALB 23 kDa protein | 94 | 36 | 23 414/5.93 |

| 2102 | IPI00220766 | GLO1 Lactoylglutathione lyase | 107 | 48 | 20 992/5.12 |

| 2410 | IPI00216691 | PFN1 Profilin-1 | 62 | 40 | 15 216/8.44 |

| Down | |||||

| 391 | IPI00021405 | LMNA Isoform A of Lamin-A/C | 204 | 42 | 74 380/6.57 |

| 509 | IPI00022463 | TF Serotransferrin precursor | 65 | 19 | 79 280/6.81 |

| 701 | IPI00878282 | ALB 23 kDa protein | 127 | 52 | 23 414/5.93 |

| 719 | IPI00553177 | SERPINA1 Isoform 1 of α-1-antitrypsin precursor | 247 | 52 | 46 878/5.37 |

| 994 | IPI00027223 | IDH1 Isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP) cytoplasmic | 150 | 50 | 46 915/6.53 |

| 1042 | IPI00021926 | PSMC6 26S protease regulatory subunit S10B | 85 | 25 | 44 430/7.10 |

| 1204 | IPI00298497 | FGB Fibrinogen β chain precursor | 204 | 46 | 56 577/8.54 |

| 1433 | IPI00455315 | ANXA2 Annexin A2 | 130 | 41 | 38 808/7.57 |

| 1442 | IPI00295889 | SRP19 Signal recognition particle 19 kDa protein | 129 | 38 | 16 374/9.87 |

| 1550 | IPI00872780 | ANXA4 Annexin A4 | 217 | 60 | 36 088/5.84 |

| 1572 | IPI00745868 | ANXA3 Uncharacterized protein ANXA3 (Fragment) | 121 | 41 | 36 623/5.53 |

| 1715 | IPI00394878 | C1QTNF1 C1q and tumor necrosis factor related protein 1 | 273 | 68 | 22 841/8.40 |

| 1856 | IPI00003766 | ETHE1 ETHE1 protein, mitochondrial precursor | 124 | 45 | 28 368/6.35 |

| 1863 | IPI00465028 | TPI1 Isoform 1 of Triosephosphate isomerase | 292 | 80 | 31 057/5.65 |

| 1890 | IPI00025512 | HSPB1 Heat shock protein β-1 | 86 | 48 | 22 826/5.98 |

| 1919 | IPI00853525 | APOA1 Apolipoprotein A1 | 191 | 64 | 28 005/5.80 |

| 1954 | IPI00220766 | GLO1 Lactoylglutathione lyase | 107 | 48 | 20 992/5.12 |

| 1961 | IPI00219622 | PSMA2 Proteasome subunit α type-2 | 275 | 70 | 25 996/ 6.92 |

| 1995 | IPI00003815 | ARHGDIA Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 | 91 | 43 | 23 250/5.02 |

| 2104 | IPI00014832 | PDK2 [Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isozyme 2 | 152 | 19 | 51 389/7.67 |

| 2237 | IPI00096066 | SUCLG2 Succinyl-CoA ligase [GDP-forming] | 184 | 23 | 46 824/6.15 |

| 2245 | IPI00384679 | RNF170 20 kDa protein | 184 | 54 | 20 773/6.40 |

| 2349 | IPI00796366 | MYL6B 16 kDa protein | 97 | 51 | 16 451/4.56 |

| 2540 | IPI00295844 | RP11-429E11.3 Novel protein | 153 | 65 | 15 089/5.49 |

| 2564 | IPI00796636 | HBB Hemoglobin (Fragment) | 98 | 64 | 11 554/5.90 |

Over-expressed proteins in sentinel lymph nodes and their function-related metastasis of cancer cells.

The 15 proteins with their expression up-regulated were then grouped and classified according to their biological functions (http://www.geneontology.org/) into cytoarchitecture reorganization- concerned proteins including VCL, PDZD8, LMNA, RUVBL1, TCP11, CLIC1, ALB and PFN1, cytometabolism-concerned proteins including SERPINB1, PURH and GLO1, and metastasis-concerned proteins including hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C and Annexin A1. The expression and distribution of these 4 metastasis-concerned proteins were further studied to assess the role they play in the progress of early CRC metastasis.

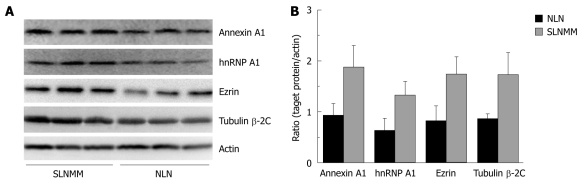

Detection of differentially expressed proteins by Western blotting

Western blotting showed that the expression level of hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C and Annexin A1, was significantly higher in SLNMM than in NLN (Figure 3A). The quantitation of protein bands showed that the expression level of the four proteins was about 2-fold higher in SLNMM than in NLN (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Western blotting (A) and quantitation of protein bands (B) showing differentially expressed hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C, and Annexin A1 in normal lymph nodes and sentinel lymph node micrometastasis. NLN: Normal lymph nodes; SLNMM: Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis.

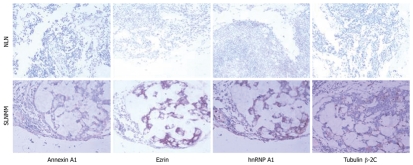

Immunohistochemical analysis of proteins in NLN and SLNMM

The representative immunohistochemistry staining of different proteins in each group is shown in Figure 4. The positive expression rate was 54.8% and 69.8% respectively for hnRNP A1, 8.1% and 87.3% respectively for Ezrin, 19.3% and 74.6% respectively for tubulin β-2C, and 14.5% and 53.9% respectively for Annexin A1, in NLN and SLNMM. Statistical analysis demonstrated that the positive expression rate for the 4 proteins was significantly higher in SLNMM than in NLN (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry analysis showing differentially expressed hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C, and Annexin A1 in normal lymph nodes and sentinel lymph node micrometastasis (× 200). NLN: Normal lymph nodes; SLNMM: Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis.

Table 2.

Expression of hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C, and Annexin A1 in normal lymph nodes and sentinel lymph node micrometastasis

| Group | Case |

hnRNP A1 |

Ezrin |

Tubulin β-2C |

Annexin A1 |

||||||||

| N | P | Rate (%) | N | P | Rate (%) | N | P | Rate (%) | N | P | Rate (%) | ||

| NLN | 62 | 28 | 34 | 54.8 | 57 | 5 | 8.1 | 50 | 12 | 19.3 | 53 | 9 | 14.5 |

| SLNMM | 126 | 38 | 88 | 69.8 | 16 | 110 | 87.3 | 32 | 94 | 74.6 | 58 | 68 | 53.9 |

| χ2 vlue | 4.11 | 109.84 | 51.57 | 26.75 | |||||||||

| P value | 0.05 > P > 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||||

NLN: Normal lymph nodes; SLNMM: Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis; N: Negative; P: Positive.

Furthermore, these four proteins were negatively or weakly expressed in NLN, but strongly expressed in SLNMM (Figure 4). Annexin A1 and hnRNP A1 were mainly expressed in cell nuclei and cytoplasm, and tubulin β-2C was mainly expressed in cell membrane. Ezrin was enriched on cell membrane surface of SLNMM, but its distribution in cytoplasm of NLN was uniform.

DISCUSSION

The proteome approach, applied in this study is of clinical importance to identify the differentially expressed proteins in NLN and SLNMM of CRC, since these proteins can be potentially used as tumor markers and anticancer targets.

We marked SLN using isosulfan blue and identified micrometastasis of CRC with HE staining and CK-IHC. The total positive rate was 42.85%, which is consistent with the reported data[20]. A total of 40 proteins were differentially expressed in NLN and SLNMM. Of these 40 proteins, 15 were up-regulated and 25 were down-regulated. The 15 proteins with their expression up-regulation were then divided into 3 groups according to their functions. Western blotting and immunohistochemistry analysis showed that the expression and distribution of 4 metastasis-concerned proteins in NLN and SLNMM were significantly different.

The Annexins are a family of calcium-regulated phospholipid-binding proteins with a diverse role in cell biology[21]. To date, 12 Annexins have been found in higher vertebrates. Although no exact physiological function of Annexins has been described, there is evidence that they are differentially expressed in various carcinomas. For example, expression of Annexins at mRNA and protein level is sharply up-regulated in many cancers[22,23], while some data indicate that declined expression of Annexins may play a significant role in tumorigenesis and metastasis[24]. So, the precise role of Annexin expression in pathogenesis of tumors is still unknown. In this study, Western blotting and IHC showed that the expression level of Annexin A1 was significantly higher in SLNMM than in NLN, suggesting that up-regulated expression of Annexin A1 may contribute to early CRC metastasis.

Ezrin, a membrane-cytoskeleton anchor, can affect cell adhesion and regulate tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Wang et al[25] reported that Ezrin expression level is obviously higher in CRC tissue than in normal colorectal mucosa tissue, which is closely related to CRC invasion and metastasis. Elzagheid et al[26] found that intense Ezrin immunoreactivity in cytoplasm can predict poor survival of CRC patients, thus providing clinically valuable information on the biological behavior of CRC. In this study, Ezrin was expressed on cell membrane surface or in cytoplasm, but not uniformly expressed in cytoplasm, which is consistent with the reported findings in pancreatic cancer[27], indicating that membrane translocation of Ezrin may also play an important role in early CRC metastasis.

Cell locomotion, including cancer cell invasion, is closely associated with dynamics of cytoskeletal structures. Tubulin isotype composition may affect polymerization properties and dynamics of microtubules. Portyanko et al[28] showed that tubulin β (III) is associated with tumor budding grade, and changes in tubulin isotypes can modulate the invading activity of CRC cells. In our study, the expression of tubulin β-2C was about 2-fold higher in SLNMM than in NLN, and IHC showed that the staining of tubulin β-2C was weak and mostly gathered around nuclei of NLN but stronger and diffused in cytoplasm of SLNMM, suggesting that the expression and distribution of tubulin β-2C are different in NLN and SLNMM of CRC, and the increased expression of tubulin β-2C is associated with early lymph node micrometastasis, thus leading to poor prognosis of CRC.

HnRNP is most abundantly expressed in nuclear protein of mammalian cells, which is associated with pre-mRNA processing and other aspects of mRNA metabolism and transport[29]. As a class of protein family, many of its subtypes are related to the occurrence of different tumors, and hnRNP A2/B1 subtype is now used as an indicator in early diagnosis of lung cancer[30]. In our study, Western blotting and IHC showed the expression level of hnRNP A1 was higher in SLNMM than in NLN, indicating that hnRNP A1 plays an important role in the occurrence and development of CRC[31,32] and can thus be considered a potential molecular indicator/biomarker of tumorigenesis in CRC.

In summary, comparative proteomics technologies can be used in study of protein profiles in NLN and SLNMM and in identification of early CRC metastasis-related proteins. Increased expression of hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C and Annexin A1 in SLN suggests a significantly elevated incidence of early CRC metastasis. However, further study is needed to verify their role in therapeutic target of CRC.

COMMENTS

Background

Tumor metastasis severely affects the prognosis and therapeutic procedures of colorectal cancer (CRC), so early detection of CRC metastasis is of great significance in improving the survival rate of CRC patients. However, no effective protein indicators of early CRC metastasis are available. Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) provide the primary lymphatic drainage of a tumor, using proteomics approach to the identification of differentially expressed proteins in SLN may be of important significance in early detection of lymph node metastasis of CRC.

Research frontiers

Comparative proteome allows the characterization of global alterations in protein expression during cancer development and has been widely used in many kinds of tumors, including CRC. Currently, studies on proteomics in CRC are mainly focused on comparison between primary CRC foci, normal tissue, and distant metastasis, or between different tumor cell lines, but the technology has not yet been used in comparison between SLN and normal lymph nodes (NLN).

Innovations and breakthroughs

Comparative proteomics technologies were used to study the protein profiles of SLN and NLN of CRC, and a number of early CRC metastasis-related proteins were identified.

Applications

Increased expression of hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin β-2C and Annexin A1 in SLN suggests a significantly elevated incidence of early CRC metastasis, which may contribute to the diagnosis of CRC and selection of its treatment modalities.

Peer review

Comparative proteomics technologies were used in this study to identify differentially expressed proteins in SLN, which may be of important significance in detection of early CRC metastasis.

Footnotes

Supported by The Natural Science Basic Research Project, Education Department of Jiangsu Province, No. 08KJT310005 and the 5th “Six Talent-Person-Peak Program”, Jiangsu Province, China; Superior Item of Nanjing Medical University Science and Technology Progress Fund, No. 07NMUM047

Peer reviewers: Sung-Gil Chi, Professor, School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Korea University, #301, Nok-Ji Building, Seoul 136-701, South Korea; Andrada Seicean, MD, PhD, Third Medical Clinic Cluj Napoca, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj Napoca, Romania, 15, Closca Street, Cluj-Napoca 400039, Romania

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2009. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2009. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf.

- 2.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:871–876. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rooney PH, Boonsong A, McKay JA, Marsh S, Stevenson DA, Murray GI, Curran S, Haites NE, Cassidy J, McLeod HL. Colorectal cancer genomics: evidence for multiple genotypes which influence survival. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1492–1498. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caplin S, Cerottini JP, Bosman FT, Constanda MT, Givel JC. For patients with Dukes' B (TNM Stage II) colorectal carcinoma, examination of six or fewer lymph nodes is related to poor prognosis. Cancer. 1998;83:666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen AM, Tremiterra S, Candela F, Thaler HT, Sigurdson ER. Prognosis of node-positive colon cancer. Cancer. 1991;67:1859–1861. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910401)67:7<1859::aid-cncr2820670707>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina-Franco H, Takahashi T, González-Ruiz GF, De-Anda J, Velazco L. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in colorectal cancer: a pilot study. Rev Invest Clin. 2005;57:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bembenek AE, Rosenberg R, Wagler E, Gretschel S, Sendler A, Siewert JR, Nährig J, Witzigmann H, Hauss J, Knorr C, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in colon cancer: a prospective multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:858–863. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250428.46656.7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bembenek A, String A, Gretschel S, Schlag PM. Technique and clinical consequences of sentinel lymph node biopsy in colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2008;17:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dionigi G, Castano P, Rovera F, Boni L, Annoni M, Villa F, Bianchi V, Carrafiello G, Bacuzzi A, Dionigi R. The application of sentinel lymph node mapping in colon cancer. Surg Oncol. 2007;16 Suppl 1:S129–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan SH, Ng C, Looi LM. Intraoperative methylene blue sentinel lymph node mapping in colorectal cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:775–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanov K, Kolev N, Ignatov V, Madjov R. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping in patients with colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roblick UJ, Auer G. Proteomics and clinical surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1464–1465. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei H, Zhu H, Zeng S, Li Y, Yang H, Shen L, Chen J, Zeng L, Fan J, Li X, et al. Proteome analysis and tissue microarray for profiling protein markers associated with lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2495–2501. doi: 10.1021/pr060644r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing X, Lai M, Gartner W, Xu E, Huang Q, Li H, Chen G. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in colorectal cancer by proteomics: down-regulation of secretagogin. Proteomics. 2006;6:2916–2923. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HJ, Kang HJ, Lee H, Lee ST, Yu MH, Kim H, Lee C. Identification of S100A8 and S100A9 as serological markers for colorectal cancer. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1368–1379. doi: 10.1021/pr8007573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu B, Li SY, An P, Zhang YN, Liang ZJ, Yuan SJ, Cai HY. Comparative study of proteome between primary cancer and hepatic metastatic tumor in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2652–2656. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i18.2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saint-Guirons J, Zeqiraj E, Schumacher U, Greenwell P, Dwek M. Proteome analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer cells recognized by the lectin Helix pomatia agglutinin (HPA) Proteomics. 2007;7:4082–4089. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fung KY, Lewanowitsch T, Henderson ST, Priebe I, Hoffmann P, McColl SR, Lockett T, Head R, Cosgrove LJ. Proteomic analysis of butyrate effects and loss of butyrate sensitivity in HT29 colorectal cancer cells. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1220–1227. doi: 10.1021/pr8009929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braat AE, Oosterhuis JW, Moll FC, de Vries JE. Successful sentinel node identification in colon carcinoma using Patent Blue V. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:633–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko I, Tanaka S, Oka S, Kawamura T, Hiyama T, Ito M, Yoshihara M, Shimamoto F, Chayama K. Lymphatic vessel density at the site of deepest penetration as a predictor of lymph node metastasis in submucosal colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.John CD, Gavins FN, Buss NA, Cover PO, Buckingham JC. Annexin A1 and the formyl peptide receptor family: neuroendocrine and metabolic aspects. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan R, Carpenter B, Main LC, Telfer C, Murray GI. Characterisation and protein expression profiling of annexins in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:426–433. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim DM, Noh HB, Park DS, Ryu SH, Koo JS, Shim YB. Immunosensors for detection of Annexin II and MUC5AC for early diagnosis of lung cancer. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;25:456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hippo Y, Yashiro M, Ishii M, Taniguchi H, Tsutsumi S, Hirakawa K, Kodama T, Aburatani H. Differential gene expression profiles of scirrhous gastric cancer cells with high metastatic potential to peritoneum or lymph nodes. Cancer Res. 2001;61:889–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang HJ, Zhu JS, Zhang Q, Sun Q, Guo H. High level of ezrin expression in colorectal cancer tissues is closely related to tumor malignancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2016–2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elzagheid A, Korkeila E, Bendardaf R, Buhmeida A, Heikkilä S, Vaheri A, Syrjänen K, Pyrhönen S, Carpén O. Intense cytoplasmic ezrin immunoreactivity predicts poor survival in colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1737–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh TS, Tseng JH, Liu NJ, Chen TC, Jan YY, Chen MF. Significance of cellular distribution of ezrin in pancreatic cystic neoplasms and ductal adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 2005;140:1184–1190. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.12.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portyanko A, Kovalev P, Gorgun J, Cherstvoy E. beta(III)-tubulin at the invasive margin of colorectal cancer: possible link to invasion. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:541–548. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buxadé M, Parra JL, Rousseau S, Shpiro N, Marquez R, Morrice N, Bain J, Espel E, Proud CG. The Mnks are novel components in the control of TNF alpha biosynthesis and phosphorylate and regulate hnRNP A1. Immunity. 2005;23:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zech VF, Dlaska M, Tzankov A, Hilbe W. Prognostic and diagnostic relevance of hnRNP A2/B1, hnRNP B1 and S100 A2 in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushigome M, Ubagai T, Fukuda H, Tsuchiya N, Sugimura T, Takatsuka J, Nakagama H. Up-regulation of hnRNP A1 gene in sporadic human colorectal cancers. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:635–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melle C, Osterloh D, Ernst G, Schimmel B, Bleul A, von Eggeling F. Identification of proteins from colorectal cancer tissue by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and SELDI mass spectrometry. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]