Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver (UESL) in adults in order to improve its diagnosis and treatment.

METHODS: Four primary and one recurrent cases of UESL were clinicopathologically evaluated and immunohistochemically investigated with a panel of antibodies using the EnVision+ system. Relevant literature about UESL in adults was reviewed.

RESULTS: Three males and one female were enrolled in this study. Their chief complaints were abdominal pain, weight loss, or fever. Laboratory tests, imaging and pathological features of UESL in adults were similar to those in children. Immunohistochemistry showed evidence of widely divergent differentiation into mesenchymal and epithelial phenotypes. The survival time of patients who underwent complete tumor resection followed by adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) was significantly longer than that of those who underwent surgical treatment alone.

CONCLUSION: UESL in adults may undergo pluripotential differentiation and its diagnosis should be made based on its morphological and immunohistochemical features. Complete tumor resection after adjuvant TACE may improve the survival time of such patients.

Keywords: Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma, Liver, Pluripotential differentiation, Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, Adult

INTRODUCTION

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver (UESL) is a rare and highly malignant spindle cell tumor, usually occurring in children and young adults[1,2]. Although UESL is generally a disease in childhood, middle-aged and elderly patients have rarely been reported[3]. To our knowledge, in the past 50 years, less than 60 adult cases have been reported[3-5]. In fact, previous reports describing its general features do not separate infants from adults, and few studies focusing on adult cases are available. Given that the majority of such patients are under the age of 30 years, adult cases over the age of 30 years are quite exceptional[5-18]. Furthermore, its detailed clinical, radiological or pathological characteristics of adult cases based on particular immunohistochemistry are not yet clear. Herein, we present 4 adult cases of UESL, and highlight its clinical features, immunohistochemical findings, and treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From 2001-2008, 4 adult cases of UESL were retrieved from the pathology files of Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China. Haematoxylin and eosin (HE) slides and all special stains were reviewed and all pathologic diagnoses were made according to the World Health Organization Histologic Classification of Liver Tumors and Intrahepatic Bile Ducts (2000)[19]. Four primary and one recurrent tumor specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Tissue was cut into 4-μm thick sections, which were stained with HE, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) with and without diastase, and trichrome, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on representative blocks using a panel of antibodies (Table 1) and the EnVision+ system. Appropriate positive and negative controls were used throughout the experiment. Staining was considered positive when > 5% of cells showed staining with the appropriate pattern, and positive but focal when the cells showed definite 1%-5% staining or patchy staining.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Clone | Source | Dilution |

| Vimentin (M) | Vim3B4 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:100 |

| α-1-antitrypsin (P) | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:100 | |

| Cytokeratin 18 (M) | DC10 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:25 |

| Cytokeratin 19 (M) | RCK108 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| CD68 (M) | PG-M1 | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:50 |

| CD56 (M) | 123C3 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| Desmin (M) | D33 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| α-SMA (M) | 1A4 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| Myoglobin (M) | MYO18 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| CD117 (P) | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:50 | |

| S-100 (M) | 4C4.9 | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:200 |

| CD34 (M) | QBEnd10 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:25 |

| Melanosome (M) | HMB-45 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:25 |

| Hep Par 1 (M) | OCH1E5 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| AFP (M) | AF04 | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:100 |

| HBsAg (M) | 3E7 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| p53 (M) | DO-7 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| pCEA (P) | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:200 | |

| mCEA (M) | COL-1 | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:50 |

| EMA (M) | E29 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:50 |

| NSE (M) | E27 | Changdao (Shanghai, China) | 1:50 |

| Chromogranin A (M) | DAK-A3 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:100 |

| Synaptophysin (M) | SY38 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:20 |

| Ki67 (M) | MIB-1 | Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) | 1:100 |

M: Monoclonal; P: Polyclonal; AFP: α-fetoprotein; HBsAg: Hepatitis B virus surface antigen; pCEA: Polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen; mCEA: Monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen; EMA: Epithelial membrane antigen; NSE: Neuron specific enolase; SMA: Smooth muscle actin.

A MEDLINE search from 1977 to July 2009 was performed with the key words “undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma” and “liver”, and the relevant literature was reviewed.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

The patients, including 3 males and 1 female, were at the age of 39, 43, 56 and 63 years, respectively. Lesions involved the right lobe in 2 cases, middle lobe in 1 case and the left lobe in 1 case. Abdominal swelling, with or without a palpable mass, and pain were usually found in the patients. Of the 4 patients, 3 complained of various non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms, fever and weight loss. Schistosomiasis was found in case 3. The clinical data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical features of undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma in adults over the age of 30 years

| No. | Ref. | Yr | Sex | Age (yr) | Symptoms and signs | Laboratory findings | Location | Size (cm) | Surgery | Adjuvanttreatment | Recurrence | Follow-up |

| 1 | Esposito et al[6] | 1977 | M | 36 | RUQA pain, hepatomegaly, jaundice | ↑Bil, AST, ALT | R + L | NA | Liver biopsy | No | NA | DOD 2 mo |

| 2 | Tanner et al[7] | 1978 | F | 66 | RUQA pain, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, fever, hepatomegaly | ↑ALP | R | NA | HA ligation | No/5-FU | v | AWD 3 yr |

| 3 | Chang et al[8] | 1983 | F | 55 | RUQA pain, weight loss, diarrhea, hepatomegaly | ↑ALT | L | 10 × 10 × 8 | Left lob | No/CAV | No | ANED 1 mo |

| 4 | Ellis et al[9] | 1983 | F | 86 | RUQA pain and mass | Normal | R | 18 × 12 × 12 | Wedge resec | No | Yes | DOD 8 wk |

| 5 | Forbes et al[10] | 1987 | M | 69 | RUQA pain, nausea, weight loss, hepatomegaly | Normal | NA | NA | No | RT/RT | NA | DOD 10 mo |

| 6 | Forbes et al[10] | 1987 | F | 49 | RUQA pain, nausea, weight loss, hepatomegaly | NA | NA | NA | No | No | NA | NA |

| 7 | Zornig et al[11] | 1992 | M | 42 | RUQA pain | Normal | R | 8 | Biseg | adm + ifs | No | ANED 30 mo |

| 8 | Zaheer et al[12] | 1994 | F | 44 | RUQA pain and mass, weight loss, fever | ↑AFP | R | 10 | Liver biopsy | adm | NA | DOD 1 wk |

| 9 | Grazi et al[13] | 1996 | F | 60 | Dyspepsia, RUQA mass | Normal | R | 22 | Rx Hep | No | Yes | DOD 11 mo |

| 10 | Nishio et al[3] | 2003 | F | 49 | RUQA pain | NA | R | 14 × 8 × 8 | Rx lob | No | Yes | DOD 29 mo |

| 11 | Nishio et al[3] | 2003 | M | 62 | RUQA pain | NA | L | 10 × 9 × 7 | Left lob | No | No | ANED 10 mo |

| 12 | Lepreux et al[14] | 2005 | F | 51 | RUQA pain | ↑AFP | R | NA | No | VAC | NA | Dead 2 mo |

| 13 | Lepreux et al[14] | 2005 | F | 49 | RUQA pain | Normal | L | NA | Left lob | ifs + dtic + adm | No | ANED 6 mo |

| 14 | Agaram et al[15] | 2006 | F | 33 | NA | NA | NA | 14.5 | NA | NA | No | ANED 6 mo |

| 15 | Agaram et al[15] | 2006 | F | 50 | NA | NA | NA | 17 | NA | NA | No | ANED 8 mo |

| 16 | Scudiere et al[4] | 2006 | F | 51 | Pneumonia | ↑AST, ALT | R | 25 × 19 × 8.5 | Rx lob | NA | NA | NA |

| 17 | Ma et al[16] | 2008 | F | 61 | RUQA pain | Normal | R | 12 × 9 × 8 | Rx hep | NA | NA | DOD 8 mo |

| 18 | Yang et al[17] | 2009 | M | 46 | RUQA pain and fever | ↑AST, ALT, GGT | R | 6.2 × 5.9 × 5.4 | Rx hep | NA | NA | NA |

| 19 | Yang et al[17] | 2009 | M | 54 | RUQA pain and fever | ↑AST, ALT, GGT | R | 13 × 11.7 × 12.4 | Rx hep | NA | NA | NA |

| 20 | Xu et al[18] | 2010 | F | 36 | RUQA pain | Normal | L | 30 × 25 × 15 | Rx hep | NA | NA | NA |

| 21 | Present case 1 | M | 63 | RUQA pain and fever | ↑AKP | R | 15 × 15 × 20 | Rx hep | NA | Yes | DOD 18 mo | |

| 22 | Present case 2 | M | 39 | weight lose and fever | ↑AKP | L | 16 × 13 × 9 | Left lob | TACE | Yes | DOD 32 mo | |

| 23 | Present case 3 | M | 56 | RUQA pain | ↑AKP, ALT, AST, GGT | R | 12.5 × 11.5 | Rx hep | TACE | Yes | DOD 28 mo | |

| 24 | Present case 4 | F | 43 | RUQA pain | ↑AKP | R | 14 × 12 × 10 | Rx hep | NA | Yes | DOD 24 mo |

R: Right; L: Left; NA: Not available; RUQA: Right upper quadrant abdominal; Rx hep: Right hepatectomy; Rx lob: Right lobectomy; Biseg: Bisegmentectomy; CAV: Cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine; VAC: Vincristine + actinomycin D + cyclophosphamide; ifs: Ifosfamide; adm: Adriamycin; dtic: Dacarbazine; DOD: Dead of disease; AWD: Alive with disease; ANED: Alive with no evidence of disease; AKP: Alkaline phosphatase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; AFP: α-fetoprotein; RT: Radiation therapy; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; HA: Hepatectomy.

Laboratory findings

The serum alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activity was slightly increased in the 4 patients. Serum α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels were within the normal range. Serum markers of hepatitis B and C virus were negative in 3 patients. However, case 3 was positive for hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B virus core antibody.

Imaging findings

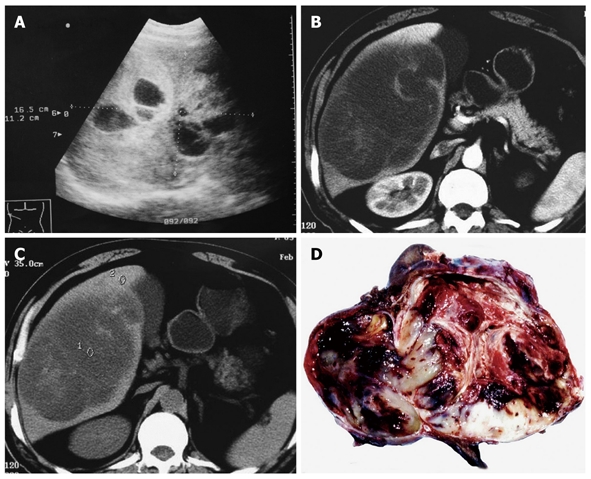

Sonography demonstrated a large confused and disorderly low level echo in the liver (Figure 1A). Computer tomography showed a hypodense and well-circumscribed mass which was multicystic in appearance with a hyperdense septum of variable thickness and dense peripheral rim corresponding to the fibrous pseudocapsule in all patients (Figure 1B and C). Complete tumor resection was performed for each patient.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasonography showing a 16.5 cm × 11.2 cm multilocular cystic liver mass (A), computed tomography imaging demonstrating a large, hypodense tumor occupying the right lobe of liver with multicystic (B) and solid portions (C), and polychromatic cut surface which is soft with fluid and mucoid zones, firm with fleshy areas and necrotico-hemorrhagic changes (D).

Gross findings

Grossly, the tumor size ranged 11-16 cm. The tumor was globular and well demarcated, but encapsulation was uncommon or incomplete. The cut surface was polychromatic and variegated tan to grey either soft with fluid and mucoid zones or firm with fleshy areas and necrotico-hemorrhagic changes (Figure 1D). The recurrent mass in one case showed similar gross features as described above.

Microscopic findings

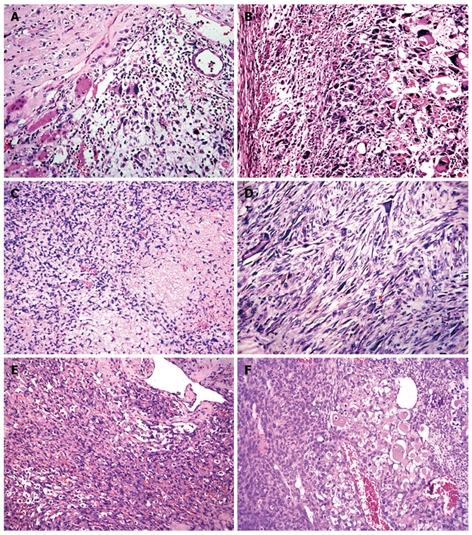

The 4 cases showed the same pathological patterns. Their tumors that were not encapsulated infiltrated the adjacent hepatic parenchyma. Entrapped bile ducts and hepatic cords were often present in areas at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2A).The tumor cells were spindle or polygonal with small and round or large and bizarre nuclei. Some cells showed marked anisonucleosis with hyperchromasia and sometimes multinucleated giant cells could be observed. The cytoplasm was slightly eosinophilic and contained sharply defined hyaline globules in varying size that were positive for diastase resistant PAS (Figure 2B). Numerous typical and atypical mitoses were observed. The mucoid areas were consisted of a loose oedematous myxoid matrix and characterized by sparse stellate atypical mesenchymal cells (Figure 2C). Hemorrhage and focal necrosis were present. Fibroblast-like or smooth muscle-like fascicles and bundles were seen in compact areas (Figure 2D). These features are typical of an undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma. In a recurrent tumor, the cells showed similar histological features to those described above. However, its cellularity and anaplasia were greater than those of the primary tumor. Focally, different types of mesenchymal differentiation were noted, such as solid spindle cell proliferation, and herringbone or chevron-, angiosarcoma-, liposarcoma-, haemangiopericytoma-, and rhabdomyosarcoma-like components (Figure 2E and F).

Figure 2.

Histology showing residual hepatocytes and bile ducts in the tumor (A), giant cells containing eosinophilic hyaline globules in the cytoplasm (B), loose oedematous myxoid matrix with sparse stellate atypical mesenchymal cells (C), fibroblast-like fascicles (D), angiosarcoma-like cells (E) and pericytoma-like and rhabdomyosarcoma-like cells (F) in compact areas (HE, × 400).

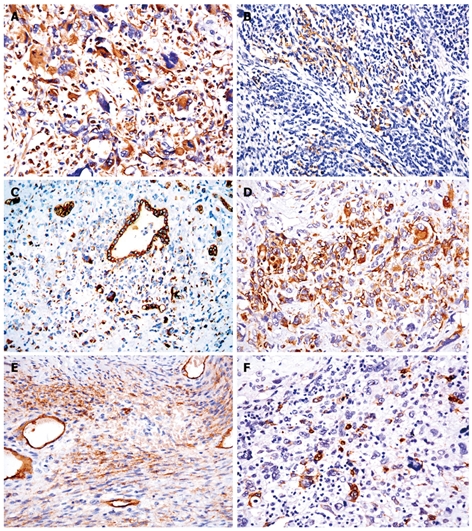

Immunohistochemical findings

Immunohistochemical staining of undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma in 4 adults is shown in Table 3. Most tumor cells were strongly reactive to vimentin (Figure 3A). Multinucleated giant cells and some spindle cells showed variable granular cytoplasmic positivity for CD68. Diffuse membranous immunostaining for CD56 was shown in all cases (Figure 3B). A diffuse multifocal cytoplasmic immunostaining was observed with a distinct paranuclear dot-like staining using cytokeratins 18 and 19 as a finding not previously described[20] (Figure 3C). Most eosinophilic hyaline globules were positive for a1-antitrypsin (a1-AT). Focal cytoplasmic positivity for desmin was found in some tumor cells (Figure 3D). However, Hep Par 1, HMB-45, CD117, CD34, HBsAg, S100, myoglobin and AFP were immunonegative in all primary cases. Compared with primary tumors, some tumor cells were focally positive for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), CD34, S100 (Figure 3E and F) and myoglobin in one recurrent tumor.

Table 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma tissue in 4 adults

| Antibody | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

Case 4 |

|

| Primary | Recurrent | ||||

| Age (yr)/sex | 63/M | 39/M | 56/M | 43/F | 44/F |

| Vimentin | + | + | + | + | + |

| α-1-antitrypsin | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cytokeratin 18 | +F | +F | - | +F | +F |

| Cytokeratin 19 | +F | +F | - | +F | +F |

| CD68 | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD56 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Desmin | - | +F | +F | - | +F |

| α-SMA | - | - | - | - | +F |

| Myoglobin | - | - | - | - | +F |

| CD117 | - | - | - | - | - |

| S-100 | - | - | - | - | +F |

| CD34 | - | - | - | - | +F |

| HMB45 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hep Par 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| AFP | - | - | - | - | - |

| HBsAg | - | - | - | - | - |

| p53 | - | - | + | + | + |

| pCEA | - | - | - | - | - |

| mCEA | - | - | - | - | - |

| EMA | - | - | - | - | - |

| NSE | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chromogranin A | - | - | - | - | - |

| Synaptophysin | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ki67 | 60% | 50% | 45% | 40% | 65% |

+F: Focal staining; AFP: α-fetoprotein; SMA: Smooth muscle actin; HBsAg: Hepatitis B virus surface antigen; EMA: Epithelial membrane antigen; NSE: Neuron specific enolase; pCEA: Polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen; mCEA: Monoclonal carcinoembryonic antigen.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry showing tumor cells strongly reactive to vimentin (A), diffuse membranous immunostaining for CD56 in mesenchymal cells (B), diffuse multifocal cytoplasmic immunostaining with a distinct paranuclear dot-like staining using cytokeratin 19 (C), focal cytoplasmic positivity for desmin in some tumor cells (D), tumor cells focally positive for α-smooth muscle actin (E) and S100 (F) (EnVision+, × 400).

Treatment and follow-up data

Follow-up imaging study with abdominal CT scan showed evidence of recurrent lesions at 9 and 30 mo after initial tumor resection in the 4 patients who died of hepatic failure due to tumor recurrence and thrombosis of intrahepatic veins after 18-32 mo of initial tumor resection. Of the 4 patients, 2 received one additional course of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE, lipiodol, epirubicin, and hydroxy camptothecin) after liver resection. The recurrent tumor occurred at 30 mo (case 2) and 14 mo (case 3) following resection, suggesting that this tumor is highly chemosensitive to TACE. Permission for an autopsy was not granted.

DISCUSSION

Clinical features

Undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma, also known as malignant mesenchymoma, mesenchymal sarcoma, undifferentiated rhabdomyosarcoma, fibromyxosarcoma and lipo fibrosarcoma of the liver, is a rare tumor, most often occurring in late childhood (at the age of 6-10 years) but infrequently in adults. The main features of these patients include a mean age of 51 years (range 33-86 years) and female preponderance. Undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma has no specific clinical features. It has been shown that children patients usually have the clinical symptoms of a large palpable mass with or without abdominal pain[21]. Some patients complain of various nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and signs, such as weight loss, nausea or anorexia, vomiting, jaundice, diarrhea, and fever[5]. However, mass and larger liver were found only in one of our cases, persistent fever and weight loss also presented in our adult cases. According to the literature, UESL is not related to hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, and the liver function and tumor markers such as AFP, CEA and CA19-9 are normal in most cases. In our adult cases, laboratory tests showed mildly elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase in one case with positive hepatitis B surface antigen due to hepatic injury. AKP was elevated in all patients. A history of schistosomiasis was first reported. The lesion could be found by ultrasound, CT and MRI. Since tumor presents as a large cystic hepatic mass, it is diagnosed as a benign lesion instead of an UESL in some cases[5]. The features of cystic change shown by CT and MRI are usually different from those of solid-to-cystic change revealed by sonography or pathology[22]. In our cases, a large confused and disorderly low level echo or a multiloculated partially cystic echo was detected by ultrasound. The cyst was characterized by hemorrhage and necrosis. In adults, the primary lesion mainly displayed cystic change, but the recurrent mass presented with solid-to-cystic change and solid type predominance. The identical result was found in one of our adult cases.

Tumor characteristics

The majority of UESL are located in the right lobe, but they can also arise in the left lobe or in the bilateral lobes simultaneously (Table 1). Macroscopically, UESL is usually a large, solitary and well-circumscribed mass with variable areas of hemorrhage, necrosis and cystic degeneration. Microscopically, it is composed of loosely arranged, medium-large spindles, oval and stellate pleomorphic cells with poorly defined cell borders, and giant cells with severe atypia. Although its pathological origin remains unclear, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies have shown its fibroblastic, histiocytic, lipoblastic, myoblastic, myofibroblastic, rhabdomyoblastic and leiomyoblastic differentiation[23]. Most UESL are diffusely positive for vimentin, a1-AT, and focally positive for cytokeratin, desmin, α-SMA, muscle-specific actin, CD68, myoglobin, non-specific enolase, S100, and CD34, suggesting that embryonal sarcoma is an ‘undifferentiated’ sarcoma, since it may display partial differentiation[23,24]. In addition, genetic alterations are complex and heterogeneous[14]. Mutated p53 and non-expression of telomerase catalytic subunit, human telomerase reverse transcriptase, may also explain its poor biological behavior.

Differential diagnosis

UESL in adults should be differentially diagnosed from carcinosarcoma, sarcomatoid or spindle-cell carcinoma, mesenchymal hamartoma, mixed hepatoblastoma with spindle-cell features, angiomyolipoma, and various other sarcomas (such as malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, angiosarcoma, liposarcoma, melanoma, rhabdomyosarcoma or malignant schwannoma[3,23]. Besides its large size, no other specific features can be used in differential diagnosis of UESL from other hepatic masses. However, the morphology and complete immunohistochemical profiles of other hepatic masses are different from those of UESL. Furthermore, the immunohistochemical profile of UESL is neither specific nor diagnostic, showing evidence of widely divergent differentiation.

Surgical management and adjuvant therapies

No consensus has been reached in standard treatment of UESL. Although the prognosis of UESL patients is very poor, it has been reported that the tumor is potentially treatable[25-28]. Complete resection with vigorous multiple approaches including chemotherapy remains the treatment of choice[29,30]. Some researchers suggested that recurrent UESL should be radically removed whenever feasible[3]. Our patients received a successful surgery, once or twice. TACE was performed in 2 cases. Recurrent UESL occurred at 30 and 14 mo, respectively, following resection, suggesting that UESL is highly sensitive to TACE. As the tumor is highly malignant and recurrent, it should be radically resected with TACE. However, careful evaluation of a larger number of patients is needed to confirm this treatment strategy.

In conclusion, UESL is still a therapeutic and diagnostic challenge. Radical resection is a treatment of choice. More attention should be paid to this peculiar disease, especially in adults.

COMMENTS

Background

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is a rare and highly malignant spindle cell tumor. Although it is generally a disease of children and young adults, middle-aged and elderly patients have rarely been reported. Previous reports describing its general features do not separate infants from adults, and few studies focusing on adult cases are available. Given that the majority of such patients are under the age of 30 years, adult cases over the age of 30 years are quite exceptional.

Research frontiers

In the past 50 years, less than 60 adult cases have been reported. Furthermore, its detailed clinical, radiological or pathological characteristics of adult cases based on particular immunohistochemistry remain unclear.

Innovations and breakthroughs

UESL in adults shows evidence of widely divergent differentiation into mesenchymal and epithelial phenotypes, and its diagnosis should be made based on morphological and immunohistochemical features. The survival time of patients who undergo complete tumor resection followed by adjuvant transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is longer than those who undergo surgical treatment alone.

Applications

The findings in this study are helpful in defining the optimal treatment for UESL patients. Complete resection after adjuvant TACE may improve the survival time of such patients.

Peer review

This is a retrospective review of a relatively rare tumor, UESL. The report outlining its clinical and pathological features is well written but fails to focus on the management strategies specific to UESL. The illustrations are clear. The discussion appears logical.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Christopher Christophi, Professor and Head, Department of Surgery, The University of Melbourne, Austin Hospital, Melbourne, 145 Studley Road, Victoria 3084, Australia

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Stocker JT, Ishak KG. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver: report of 31 cases. Cancer. 1978;42:336–348. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197807)42:1<336::aid-cncr2820420151>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lack EE, Schloo BL, Azumi N, Travis WD, Grier HE, Kozakewich HP. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver. Clinical and pathologic study of 16 cases with emphasis on immunohistochemical features. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Sakashita N, Haraoka S, Isayama T, Naito M, Miyayama H, Yamashita Y, Kikuchi M. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver in middle-aged adults: smooth muscle differentiation determined by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:246–252. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scudiere JR, Jakate S. A 51-year-old woman with a liver mass. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:e24–e26. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-e24-AYWWAL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pachera S, Nishio H, Takahashi Y, Yokoyama Y, Oda K, Ebata T, Igami T, Nagino M. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: case report and literature survey. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:536–544. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esposito R, Pollavini G, de Lalla F. A case of primary undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver. Endoscopy. 1977;8:108–110. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1098390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanner AR, Bolton PM, Powell LW. Primary sarcoma of the liver. Report of a case with excellent response to hepatic artery ligation and infusion chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:121–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang WW, Agha FP, Morgan WS. Primary sarcoma of the liver in the adult. Cancer. 1983;51:1510–1517. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830415)51:8<1510::aid-cncr2820510826>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis IO, Cotton RE. Primary malignant mesenchymal tumour of the liver in an elderly female. Histopathology. 1983;7:113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forbes A, Portmann B, Johnson P, Williams R. Hepatic sarcomas in adults: a review of 25 cases. Gut. 1987;28:668–674. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.6.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zornig C, Kremer B, Henne-Bruns D, Weh HJ, Schröder S, Brölsch CE. Primary sarcoma of the liver in the adult. Report of five surgically treated patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39:319–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaheer W, Allen SL, Ali SZ, Kahn E, Teichberg S. Primary multicystic undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in an adult presenting with peripheral eosinophilia. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1994;24:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grazi GL, Gallucci A, Masetti M, Jovine E, Fiorentino M, Mazziotti A, Gozzetti G. Surgical therapy for undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcomas of the liver in adults. Am Surg. 1996;62:901–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepreux S, Rebouissou S, Le Bail B, Saric J, Balabaud C, Bloch B, Martin-Négrier ML, Zucman-Rossi J, Bioulac-Sage P. Mutation of TP53 gene is involved in carcinogenesis of hepatic undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the adult, in contrast with Wnt or telomerase pathways: an immunohistochemical study of three cases with genomic relation in two cases. J Hepatol. 2005;42:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agaram NP, Baren A, Antonescu CR. Pediatric and adult hepatic embryonal sarcoma: a comparative ultrastructural study with morphologic correlations. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:403–408. doi: 10.1080/01913120600854699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma L, Liu YP, Geng CZ, Tian ZH, Wu GX, Wang XL. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver in an old female: case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7267–7270. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Chen LB, Xiao J, Han P. Clinical features and spiral computed tomography analysis of undifferentiated embryonic liver sarcoma in adults. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu HF, Mao YL, Du SD, Chi TY, Lu X, Yang ZY, Sang XT, Zhong SX, Huang JF. Adult primary undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: a case report. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:250–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishak KG, Anthony PP, Niederau C, Nakanuma Y. Mesenchymal tumours of the liver. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. pp. 194–195. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Gómez RM, Soria-Céspedes D, de León-Bojorge B, Ortiz-Hidalgo C. Diffuse membranous immunoreactivity of CD56 and paranuclear dot-like staining pattern of cytokeratins AE1/3, CAM5.2, and OSCAR in undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:195–198. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181bb2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron PW, Majlessipour F, Bedros AA, Zuppan CW, Ben-Youssef R, Yanni G, Ojogho ON, Concepcion W. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver successfully treated with chemotherapy and liver resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:73–75. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Marshall WH, Ros PR, Levine MS, Goodman ZD. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver: pathologic basis of imaging findings in 28 cases. Radiology. 1997;203:779–783. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng JM, Tao X, Xu AM, Chen XF, Wu MC, Zhang SH. Primary and recurrent embryonal sarcoma of the liver: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Histopathology. 2007;51:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiani B, Ferrell LD, Qualman S, Frankel WL. Immunohistochemical analysis of embryonal sarcoma of the liver. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006;14:193–197. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000173052.37673.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leuschner I. Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma: histologic variant of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma with association to favorable prognosis. Curr Top Pathol. 1995;89:261–272. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77289-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez-Crussi F. Undifferentiated (embryonal) liver sarcoma of childhood: evidence of leiomyoblastic differentiation. Pediatr Pathol. 1983;1:281–290. doi: 10.3109/15513818309040665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bisogno G, Pilz T, Perilongo G, Ferrari A, Harms D, Ninfo V, Treuner J, Carli M. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver in childhood: a curable disease. Cancer. 2002;94:252–257. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DY, Kim KH, Jung SE, Lee SC, Park KW, Kim WK. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver: combination treatment by surgery and chemotherapy. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1419–1423. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenze F, Birkfellner T, Lenz P, Hussein K, Länger F, Kreipe H, Domschke W. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in adults. Cancer. 2008;112:2274–2282. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Sullivan MJ, Swanson PE, Knoll J, Taboada EM, Dehner LP. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma with unusual features arising within mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:482–489. doi: 10.1007/s10024001-0047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]