Abstract

We have previously documented inequalities in the quality of medical care provided to those with mental ill health but the implications for mortality are unclear. We aimed to test whether disparities in medical treatment of cardiovascular conditions, specifically receipt of medical procedures and receipt of prescribed medication, are linked with elevated rates of mortality in people with schizophrenia and severe mental illness. We undertook a systematic review of studies that examined medical procedures and a pooled analysis of prescribed medication in those with and without comorbid mental illness, focusing on those which recruited individuals with schizophrenia and measured mortality as an outcome. From 17 studies of treatment adequacy in cardiovascular conditions, eight examined cardiac procedures and nine examined adequacy of prescribed cardiac medication. Six of eight studies examining the adequacy of cardiac procedures found lower than average provision of medical care and two studies found no difference. Meta-analytic pooling of nine medication studies showed lower than average rates of prescribing evident for the following individual classes of medication; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 6, aOR = 0.779, 95% CI = 0.638–0.950, p = 0.0137), beta-blockers (n = 9, aOR = 0.844, 95% CI = 0.690–1.03, p = 0.1036) and statins (n = 5, aOR = 0.604, 95% CI = 0.408–0.89, p = 0.0117). No inequality was evident for aspirin (n = 7, aOR = 0.986, 95% CI = 0.7955–1.02, p = 0.382). Interestingly higher than expected prescribing was found for older non-statin cholesterol-lowering agents (n = 4, aOR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.04–2.32, p = 0.0312). A search for outcomes in this sample revealed ten studies linking poor quality of care and possible effects on mortality in specialist settings. In half of the studies there was significantly higher mortality in those with mental ill health compared with controls but there was inadequate data to confirm a causative link. Nevertheless, indirect evidence supports the observation that deficits in quality of care are contributing to higher than expected mortality in those with severe mental illness (SMI) and schizophrenia. The quality of medical treatment provided to those with cardiac conditions and comorbid schizophrenia is often suboptimal and may be linked with avoidable excess mortality. Every effort should be made to deliver high-quality medical care to people with severe mental illness.

Keywords: Mortality, quality of care, schizophrenia, severe mental illness, substance abuse

Introduction

There is longstanding and conclusive evidence that the physical health of people with severe mental illness (SMI) is poor compared with the general population (Mitchell and Malone, 2006; Prince et al., 2007). Amongst those with mental illness there is a higher than expected mortality rate and a lower life-expectancy with a persistent mortality gap over several decades (Saha et al., 2007). Individuals with schizophrenia appear to have higher rates of hypothyroidism, dermatitis, eczema, obesity, epilepsy, viral hepatitis, diabetes (type II), essential hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and fluid/electrolyte disorders (Carney et al., 2006; Weber et al., 2009). The presence of this medical comorbidity adversely effects quality of life and recovery from the underlying psychiatric disorder (Kisely and Simon, 2005). Although many of these chronic conditions may be unavoidable given our current state of knowledge, many deaths in SMI are considered avoidable (Amaddeo et al., 2007; Crompton et al., 2010). In addition up to half of all chronic conditions go unrecognized in schizophrenia (Bernardo, 2006; Farmer, 1987; Fallow et al., 1995; Korany, 1979; Klilbourne et al., 2006). For example, in a study of the homeless mentally ill 43.6% had an unmet need for medical care (Desai and Rosenheck, 2005). Many studies suggest that mental health professionals often miss physical conditions in their patients (Felker et al., 1996; Koran et al., 1989) and rarely undertake physical examinations of their patients (McIntyre and Romano, 1977; Patterson, 1978).

What has only recently become clear is that the quality of medical care provided to those with known mental health diagnoses is also less than ideal. Medical care can be divided into the care for those with established medical comorbidity and screening/preventive practices for those at risk of medical illness. Medical care includes medical treatment and processes of care such as investigations and monitoring. Patients with SMI appear to suffer in all areas. Also in question is the delivery of appropriate preventive screening services. Lack of screening and related services is important not just for the reduction in future morbidity but low receipt of preventive care is associated with lower quality of life (Mackell et al., 2005). An analysis of National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data showed that psychiatrists provided preventive services to people with SMI during only 11% of visits (Daumit et al., 2002). Our group recently evaluated 27 studies that examined receipt of medical care in those with and without mental illness (Mitchell et al., 2009). The majority of studies demonstrated significant inequalities in the quality of care received by patients with SMI against those without SMI. We also reviewed 25 studies that examined preventive care in individuals with versus without psychiatric illness. For those individuals with schizophrenia eight of nine analyses showed inferior preventive care in several areas including osteoporosis screening, blood pressure monitoring, vaccinations, mammography and cholesterol monitoring (Lord et al., 2010). The magnitude deficits in quality of care vary considerably according to the setting and method of data collection. In some of these studies the magnitude of the inequality approaches 50% of the comparative standard but in other domains differences were quite subtle.

Given that mortality rates are high and quality of care is less than optimal, an important question is are these two factors linked? We already know that successful medical mass screening programmes have the potential to improve survival (Kerlikowske et al., 1995; Heresbach et al., 2006; Lindholt and Norman 2008). If deficits in quality of medical care or preventive services directly influence survival in those with schizophrenia then some responsibility for poor outcomes must rest with healthcare professionals. In this review, we aim to examine the hypothesis that suboptimal cardiac treatment (one facet of medical care) influences mortality in those with schizophrenia.

Methods

We searched Medline and Embase databases from inception to May 2010. In these databases the keywords/MeSH terms (‘comorbidity or comorbidity’ or ‘organic or physical or medic* or cardia’) and (‘psychi* or mental or depress* or schizophr* or severe mental illness or SMI’) were used. We included those with SMI provided there was a subgroup with schizophrenia. Four full-text collections were searched: Science Direct, Ingenta Select, Springer-Verlag’s LINK and Blackwell-Wiley. In these online databases the same search terms were used but as a full text search and as a citation search. The abstract databases Web of Knowledge and Scopus were searched, using the above terms as a text word search, and using key papers in a reverse citation search. Finally, a number of journals were hand-searched and several experts contacted. Using this strategy we located 440 references but only 80 were primary data studies. From these we identified 18 studies regarding treatment adequacy and eight studies that examined both mortality and quality of care by psychiatric diagnosis. We excluded studies purely focusing on depression (Goodwin et al., 2004). We pooled data from treatment data using adjusted odds ratios (aORs) provided by the original authors and converting hazard ratios to odds ratios (ORs) where needed. We used random effects meta-analysis as I2 heterogeneity was above 75%.

Results

Adequacy of medical treatment

From 17 studies of treatment adequacy, eight examined cardiac procedures (Table 1) and nine examined adequacy of prescribed medication for cardiac conditions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of studies linking mortality and quality of care in cardiac patients with schizophrenia (or severe mental illness)

| Author and Year | Measure of quality of Care/ Medical treatment | Sample | Setting | Comment | Effect on Mortality | Quality of Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Druss et al. (2000) US (Medicare) | • Cardiac care treatment: Likelihood of CC, PTCA or CABG | National cohort 113,653 >64 years, hospitalized for a confirmed myocardial infarction. 5365 had a diagnosis of mental illness Data from Medicare acute care nongovernmental hospitals Controlled for demographic, clinical, hospital, and regional variables | Hospitalized patients | Patients with any comorbid mental illness less likely to undergo • PTCA (11.8% vs. 16.8% p < 0.001) • CABG (8.2% vs.12.6% p < 0.001) Those with mental illness were 41% (for schizophrenia) to 78% (for substance use) less likely to undergo CC compared to those without mental illness (p < 0.001 for all). Among those having CC there was no significant difference in rates of PTCA or CABG between those with and without mental illness. | Patients with mental disorders had a small but statistically significantly lower risk of mortality at baseline. Unadjusted 12.8% of those with schizophrenia died within 30 days compared with 10.8% in comparator population but this was not significant after adjustments. | Mentally ill and substance users received lower levels of care on all measures. |

| Druss et al. (2001) US (Medicare) | Cardiac care post MI mortality before and after considering 5 quality indicators • Reperfusion therapy • Aspirin • b-Blockers • ACE inhibitors • Smoking cessation counselling | 88,241 Medicare patients hospitalized for a clinically confirmed myocardial infarction. Data from Medicare controlled for eligibility for procedure, demographics, cardiac risk factors, left ventricular function, admission and hospital characteristics and regional factors. | Hospitalized patients | After adjusting for potential confounding factors, presence of any secondary mental disorder predicted a 13% decreased likelihood of reperfusion therapy in ‘ideal’ candidates and 26% reduction in ‘eligible but not ideal’ Such patients were also about 10% less likely to receive aspirin, b-blockers, ACE inhibitors As compared with those without a psychiatric disorder, patients with schizophrenia were less likely to have reperfusion, b-blockers and ACE inhibitors. Patients with affective disorders were less likely to have reperfusion and aspirin and those with substance use disorders were less likely to be given ACE inhibitors. | Mental illness of all types associated with a 19% increase in mortality at 1 yr. HR = 1.19 (95% CI 1.04–1.36). Schizophrenia had a higher mortality with HR 1.34 (95% CI 1.01–1.67) When the 5 quality measures were added to the model the association was no longer significant. Concluding that deficits in quality of care explain a substantial proportion of the excess mortality of patients with mental illness after MI. | Mentally ill received lower levels of care on all measures. Patients with schizophrenia had particulars high risk of poor care. |

| Jones and Carney (2005) US (Medicare) | Cardiac care treatment: Likelihood of PTCA or CABG | Blue cross/blue shield database for claims. 3368 adults hospitalized for a MI. 40% (1342) diagnosed as having a first mental disorder within the first 30 days of MI. Mental disorder identified from insurance claims between 1996 and 2001 and associated ICD 9 codes. Includes unspecified number with schizophrenia. Adjusted for demographic and clinical characteristics (Adjusted for age, gender, number of days hospitalized, residence, hospital transfer, cardiovascular risk factors and other medical comorbidity). | Hospitalized patients | No significant difference in rates of revascularization were demonstrated. | ||

| Kisely et al. (2007) Canada | Cardiac care treatment: Rate of receiving revascularization procedures | 215 889 individuals from Nova Scotia's Mental Health comprising 13,626 specialized or revascularization procedures (1685 in psychiatric patients). Includes unspecified number with schizophrenia. Results were adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status and comorbid illness. | Secondary care | In psychiatric inpatients the adjusted rate ratios for CC, PTCA and CABG were 0.41, 0.22 and 0.34, respectively, in spite of psychiatric inpatients' increased risk of death. | The age-standardized mortality-rate ratio for psychiatric patients was 1.31 (95% CI 1.25–1.36). | Psychiatric patients were no more likely (or in some cases less likely) to undergo any of the 5 procedures than were the general population. |

| Lawrence et al. (2003) Australia | Cardiac care in IHD • SMR due to IHD • Revascularization procedures (removal of coronary art obstruction and CABG) | Western Australia linked database used to identify 210,129 users of mental health users and diagnosis (ICD 9 dx). Note hierarchical model used so most severe diagnosis carried forward and coded as the main diagnosis. Note psychiatric diagnosis examined included dementia. Unable to adjust for demographic and clinical characteristics | Secondary care | Revascularization rates low for dementia followed by those with schizophrenia, substance disorder, other psychoses and affective psychoses (rate ratios 0.14, 0.31, 0.60, 0.66, 0.77 respectively) but significant only for men. The only significant difference in revascularization in women was in those with schizophrenia with a rate ratio of 0.34 (95% CI 0.18–0.64) | SMRs due to IHD in mental health users almost twice that in overall population (SMR 1.91 total IHD, 1.74 acute MI). Majority of deaths ascribed to MI (59%). Significant increase in mortality rates seen in females with psychiatric diagnosis, compared to a reduction over time in the normal population. | Mentally ill received lower levels of care but this was significant only for men. |

| Li et al. (2007) US | Cardiac care in CHD OR of receiving • CABG from a ‘high-mortality’ surgeon • CABG from a ‘Low-mortality’ surgeon | 39,839 individuals who had CABG in New York state of whom 2651 had psychiatric disorder (20% with schizophrenia) and 447 substance use disorder. 113 had dual-diagnosis. Results were adjusted for socio demographic and clinical characteristics as well as surgeon work volume. | Secondary care | Patients with mental illness had an OR of 1.28 (OR = 0.023) for receipt of care from a high mortality surgeon. No effect for substance use group alone or dual diagnosis, although sub-sample size was small. | Not measured | Patients with mental illness were more likely to have treatment from low quality surgeons |

| Petersen et al. (2003) US (VA) | Cardiac care post MI Examined age adjusted RR for: thrombolytic therapy; use of medications at discharge (b-blockers, ACE inhibitors, aspirin) | 4340 veterans discharged after a clinically confirmed MI. 859 (19.8%) had mental illness (identified if had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, received a mental health diagnosis or been seen in a psychiatric or drug/alcohol clinic, all in the year before. Includes unspecified number with schizophrenia. Controlled for age, Comorbidity and hospital characteristics. | Secondary care | Those with mental illness less likely to undergo inpatient diagnostic angiography, age adjusted RR = 0.9 (95% CI 0.83–0.98). No difference in RR of CABG, receipt of meds. Risk adjusted OR of death at 30/7 =1 (95 CI 0.75–1.32) and 1 yr = 1.25 (CI 1.00, 1.53) did not reach statistical significance. | Trend towards higher rate of death at 1 year in those with mental illness | Mentally ill group received lower levels of angiography but not CABG or medication offered. |

| Plomondon et al. (2007) US | Acute coronary syndromes Rate of cardiac procedures | 14,194 patients (including 18% with mental illness and 406 with schizophrenia Setting was VHA | Secondary care | Among eligible patients, there were no significant differences in the rates of receipt of diagnostic coronary angiogram and coronary revascularization between patients with and without SMI. At hospital discharge, there were similar prescription rates for aspirin, ACE-inhibitor/ARB, and b-blocker medications between the patient groups. | One-year mortality was lower for patients with SMI (15.8% vs. 19.1%, p < 0.001). However, in multivariable analysis, there were no significant differences in mortality (HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.81–1.02) between patients with and without SMI. For schizophrenia this was (0.83; 95% CI 0.60–1.15) | There were no significant differences in cardiac procedure use, including coronary angiogram (38.7% vs. 40.3%, p = 0.14) or coronary revascularization (31.0% vs. 32.3%, p = 0.19), and discharge medications between those with and without SMI. |

| Young et al. (2000) US | Cardiac care post MI Likelihood of • CC • PTCA • CABG | Healthcare investment analysis (HCIA)-Sachs data base. 354,195 patients included with a principal diagnosis of acute MI (143,421, 40.5% under 65 yrs). Using definitions similar to Druss et al., 2000 identified 25,237 (7.1%) with mental illness. None of the data adjusted for admission characteristics or left ventricular function. | Hospitalized patients | Those with mental illness significantly less likely to undergo CC, PTCA or CABG. Those with schizophrenia had had the Disparities were greater in older patients. In those aged 65 years or older rates of CC were as follows (all statistically significant). Schizophrenia RR 0.52, affective disorders RR 0.8, substance use RR 0.9. In this age group the odds of PTCA for a patient with schizophrenia was 32% the rate in those without mental illness | Mortality during admission lower in the older than 65 group with mental disorders with a 21% lower risk adjusted likelihood of death (p < 0.001) compared with those without mental illness. Younger group with mental illness had a higher inpatient mortality rate for those with schizophrenia (p < 0.001) and substance abuse (p < 0.001). | Mentally ill (and substance users) received lower levels of care on all measures Need to interpret with caution as unadjusted data |

CC, cardiac catheterization; PTCA. percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; MI, myocardial infarction; IHD, ischemic heart disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; SMR, standardized mortality rate; VHA, veterans health administration; SMI, severe mental illness; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

Table 2.

Summary of comparative studies reporting on receipt of cardiac medication in patients with schizophrenia (or severe mental illness)

| Author (country) | Treatment | Mental illness types | Sample | Setting | Result | Statistical summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desai et al. (2002b) US (VA) | Cardiac care treatment, use of aspirin, use of b-blockers | ICD9 defined schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder | National sample of 5886 veterans discharged from VHA hospitals with a principal diagnosis of acute MI up to 6 months before the index study date. Overall, 27.4% had a diagnosed mental illness. Aged under 65 years. Controlled for age, sex, race, level of VHA service connectedness and distance from veteran’s home to nearest VHA medical facility, chronic medical conditions and use of medical services in the past year (number of primary care visits, number of specialty medical visits, and number of medical inpatient days) and hospital size. | Community patients | In fully adjusted analyses, use of b-blockers was 5% less likely among patients with a substance use disorder compared with those with no such disorder. Aspirin 181/188 vs. 5233/5423 HR 0.938822 95%CI 0.446455 –2.368385 b-blocker 170/188 vs. 5070/5423 0.7 HR b-blocker 0.43–1.2 | Aspirin OR = 1.07 (95% CI 0.49–2.3) b-blocker OR = 0.70 (95% CI 0.43–1.15) cholesterol OR = 1.01 (95%CI 0.369–2.77) |

| Druss et al. (2001) US (Medicare) | Cardiac care treatment Reperfusion therapy, aspirin, beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors. | ICD9 definition: any mental disorder (n = 4664) Schizophrenia (n = 161) Affective disorder (n = 271) Substance use disorder (n = 882) | 88,241 Medicare patients hospitalized for a clinically confirmed MI. Data from Medicare controlled for eligibility for procedure, demographics, cardiac risk factors, left ventricular function, admission and hospital characteristics and regional factors. | Hospitalized patients | As compared with those without a psychiatric disorder, patients with schizophrenia were less likely to have reperfusion, b-blockers and ACE inhibitors. Patients with affective disorders were less likely to have reperfusion and aspirin and those with substance use disorders were less likely to be given ACE inhibitors | ACE OR = 0.814 (95% CI 0.654–0.983) Aspirin OR = 0.807 (95% CI 0.652–0.975) b-Blocker OR = 0.845 (95% CI 0.722–0.984) |

| Hippisley-Cox et al. (2007) UK | Cardiac care treatment RRs of receiving statins, prescription for aspirin, antiplatelets, anticoagulants or b-blockers. | Schizophrenia from EMIS medical records system (primary care record) | 127,932 patients with CHD of whom 701 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. The results were adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, diabetes, stroke and smoking status, and allowed for clustering by practice. | Primary care | Although there were no differences in several parameters, patients with schizophrenia were 15% less likely to have a recent prescription for a statin (95% CI 8% to 20%) and 7% less likely to have a recent record of cholesterol level (95% CI 3% to 11%) than those without mental illness. | b-Blocker OR = 0.96 (95% Cl 0.88–1.06) asprin OR = 1 (95% CI 0.97–1.04) statin OR = 0.85 (95% CI 0.8– 0.91) |

| Petersen et al. (2003) US (VA) | Cardiac care treatment examined age adjusted RR for thrombolytics and use of meds at discharge (b-Blockers, ACE inhibitors, aspirin). | ICD9 defined or problems were patients who had an admission to an inpatient psychiatric or substance abuse unit in the year prior to cardiac admission. | 4340 veterans discharged after a clinically confirmed MI. 859 (19.8%) had mental illness (identified if had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, received a mental health diagnosis or been seen in a psychiatric or drug/alcohol clinic, all in the year before). Includes unspecified number with schizophrenia. Controlled for age, comorbidity and hospital characteristics. | Secondary care | Those with MI less likely to undergo inpatient diagnostic angiography, age adjusted RR = 0.9 (95% CI 0.83–0.98). No difference in RR of CABG or receipt of meds. | ACE inhibitor OR = 0.919 (95% CI 0.786–1.09) aspirin OR = 0.959 (95% CI 0.812–1.15) b-blocker OR = 0.784 (CI 0.686–0.915) |

| Plomondon et al. (2007) US | Rate of cardiac procedures. | ICD9 defined 18.4% (n = 2,623) of the study population had a diagnosis of SMI. Of the patients with SMI, 65.5% (n = 1718) had a diagnosis of anxiety disorder, 47.1% (n = 1235) had a diagnosis of mood disorder, 15.5% (n = 406) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 11.7% (n = 307) had a diagnosis of personality disorder (not mutually exclusive categories). | 14,194 patients (including 18% with mental illness and 406 with schizophrenia). Setting was VHA. | Hospitalized patients | There were no significant differences in cardiac procedure use, including coronary angiogram (38.7% vs. 40.3%, p = 0.14) or coronary revascularization (31.0% vs. 32.3%, p = 0.19), and discharge medications between those with and without SMI. | ACE inhibitor OR = 0.926 (95% CI 0.841– 012) aspirin OR = 0.93 (95% CI 0.83–1.044) b-blocker OR = 1.11 (95% CI 0.97–1.28) |

| Weiss et al. (2006) US | ACE inhibitor or ARB antihypertensive medication | Schizophrenia by ICD-9 code (295,297, or 298), as having a psychotic disorder. | 214 patients with schizophrenia or a schizophrenia-related syndrome vs. 3594 with diabetes but no severe mental illness. | Mixed settings | Patients with elevated blood glucose (HbA1c greater than 7%) were taking a hypoglycaemic medication (92% of comparison patients and 95% of schizophrenia patients). However, patients with schizophrenia were slightly more likely than comparison patients to specifically receive insulin therapy (47% compared with 38%); aOR = 1.44, p = 0.08). In addition, although the patients with hyperlipidemia in the two groups were equally likely to receive some form of lipid-lowering therapy, those with schizophrenia were significantly more likely to receive one of the older, NS agents (14% compared with 7%; aOR=1.85, p < 0.05). | ACE inhibitor OR = 0.83 aspirin OR = 0.89 (95% CI 0.64–1.24) b-blocker OR = 0.96 (95% CI 0.54–1.71) insulin OR = 1.44 (95% CI 0.96–2.16) cholesterol NS OR = 1.85 (95% CI 1.11–3.09) statin OR = 0.54 (CI 0.36– 0.51) |

VHA, Veterans Health Administration; MI, myocardial infarction; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; CHD, coronary heart disease; NS, non-statin; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted OR; RR, relative risk.

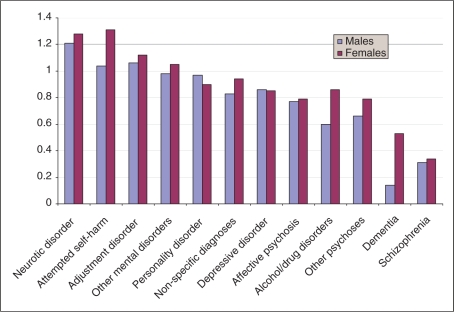

Looking at cardiac procedures first, Druss et al. (2000) examined cardiovascular care following an acute myocardial infarction. After adjusting for demographic, clinical, hospital and regional factors, those with mental disorders were only 41% (for schizophrenia) to 78% (for substance use) as likely to undergo cardiac catheterization as those without mental disorders. Druss et al. (2001) also found patients hospitalized for myocardial infarction with mental health diagnoses were less likely to have reperfusion conducted. Young and Foster (2000) found those with a mental illness post-myocardial infarction had significantly lower levels of all three revascularization procedures (cardiac catheterization, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA] and coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]) compared with those without mental illness, with the lowest rates seen in those older than 64 years. Petersen et al. (2003) examined the records of 4340 male veterans discharged after a clinically confirmed myocardial infarction. In this study those with mental illness were less likely to undergo inpatient diagnostic angiography (age adjusted relative risk [RR] = 0.9; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.83–0.98) but with no difference in CABG. Lawrence et al. (2003) conducted a population-based record-linkage study of 210,129 users of mental health services in Western Australia during 1980–1998. They found revascularization rates were low for people with dementia followed by those with schizophrenia, substance disorder, other psychoses and affective psychoses (rate ratios 0.14, 0.31, 0.60, 0.66, 0.77, respectively) but significant only for men (Figure 1). Kisely et al. (2007) carried out a population-based record-linkage analysis of related data from 1995 to 2001 compared with the general public for each outcome (n = 215,889). In psychiatric inpatients the adjusted rate ratios for cardiac catheterization, PTCA and CABG were 0.41, 0.22 and 0.34, respectively. However, Plomondon et al. (2007) found no differences in cardiac procedure after acute coronary syndromes presenting to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospitals and similarly Jones and Carney (2005) found no difference in the rates of revascularization. Thus, six from eight studies found lower than average rates of cardiac procedures in those with a psychiatric history treated for cardiac complaints.

Figure 1.

Revascularization procedure rate ratios (95% confidence intervals) comparing users of mental health services with the general community, by procedure type and principal psychiatric diagnosis. (Data adapted from Lawrence et al. (2003)).

Regarding adequacy of prescribed medication we found nine analyses relating to five classes of medication (Table 2). These comprised statins, non-statin cholesterol agents, beta-blockers, aspirin and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). After rates were adjusted for potential confounders and pooled using meta-analysis the following results were apparent. Of these studies low prescribing was evident for the following individual classes of medication. ACE/ARBs (n = 6, aOR = 0.779, 95% CI = 0.638–0.950, p = 0.0137), beta-blockers (n = 9, aOR = 0.844, 95% CI = 0.690–1.03, p = 0.1036) statins (n = 5, aOR = 0.604, 95% CI = 0.408–0.89, p = 0.0117). No inequality was evident for aspirin (n = 7, aOR = 0.986, 95% CI = 0.955–1.02, p = 0.3819). Provisionally, higher than expected prescribing was found for older non-statin cholesterol-lowering agents (n = 4, aOR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.04–2.32, p = 0.0312).

Quality of care and mortality

In the study from Druss et al. (2000), patients with mental disorders had a small but statistically significantly lower risk of mortality at baseline and in unadjusted analysis 12.8% of those with schizophrenia died within 30 days compared with 10.8% in the comparator population but this was not significant after adjustments. Yet in their replication study Druss et al. (2001) found that mental disorder of all types was associated with a 19% increase in mortality at one year. Importantly, when the five quality indicators were added to the model this association was no longer significant, suggesting that elevated mortality is related to poor quality of care. Young and Foster (2000) found that in the older cohort (older than 65 years) with mental illness there was a 21% lower risk adjusted likelihood of death (p < 0.001) compared with those without mental illness. In the younger cohort those with schizophrenia and substance abuse had higher inpatient mortality rates (both p < 0.001). Thus, age may play an important role in modifying risk. Petersen et al. (2003) examined the records of 4340 male veterans discharged after a clinically confirmed myocardial infarction. The authors found a trend towards higher rate of death at one year in those with mental illness; risk for death within one year was 1.25 (95% CI 1.00–1.53). In the study from Lawrence et al. (2003) ischemic heart disease (not suicide) was the major cause of excess mortality in psychiatric patients. Standardized mortality rates (SMRs) due to ischemic heart disease in mental health users were almost twice that in the overall population (SMR 1.91 total ischemic heart disease, 1.74 acute myocardial infarction). Males with schizophrenia were only 60% as likely to be admitted for ischemic heart disease compared with males in the general population, despite being 1.8 times as likely to die from ischemic heart disease. Kisely et al. (2007) carried out a population-based record-linkage analysis of related data from 1995 through 2001 compared with the general public for each outcome (n = 215,889). The age-standardized mortality-rate ratio for psychiatric patients was 1.31 (95% CI 1.25–1.36). Psychiatric patients were often cases less likely to undergo any of the cardiac procedures than were the general population. Plomondon et al. (2007) studied 14,194 patients (including 18% with SMI) with acute coronary syndromes presenting to VHA hospitals between October 2003 and September 2005 and although one year mortality was lower for patients with SMI (15.8% vs. 19.1%, p < 0.001) there was no difference in quality of care. Interestingly Li et al. (2007) analysed New York State hospital discharge data between 2001 and 2003 and New York's publicly-released Cardiac Surgery Report of surgeons' risk-adjusted mortality rate. After adjustments patients with both substance-use and psychiatric disorders (n = 113), but not substance-use alone (n = 447), were more likely to receive care from surgeons in the high-mortality quintile group (OR = 1.76, p = 0.024).

Discussion

National guidelines are agreed that the medical care of patients with mental disorders and schizophrenia in particular is paramount (Department of Health, 1999; De Hert et al., 2009; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2009; Unützer et al., 2006). Unfortunately there is little evidence that this advice is being heeded. Indeed serious concerns have been raised about the quality of medical (and screening) services offered to patients with SMI (Mitchell et al., 2009; Lord et al., 2010). In spite of higher than average risks of physical ill health and premature mortality, individuals with schizophrenia receive as little as half of the monitoring offered to people without schizophrenia in some studies (Roberts et al., 2007). Our previous work found that they also receive less adequate quality of care for established medical conditions (Desai et al., 2002a; Redelmeier et al., 1998; Vahia et al., 2008). These disparities exist in some of the most critical areas of patient care such as general medicine, cardiovascular and cancer care (Mateen et al., 2008). In this review, we extend these findings to cardiac treatment as well as associated poor outcomes in terms of elevated mortality. In particular, we found that six of eight studies examining the adequacy of cardiac procedures in patients with schizophrenia and related conditions found lower than average provision of medical care although two studies found no difference. From nine medication studies lower than average rates of prescribing were evident for the following individual classes of medication: ACE/ARBs, beta-blockers and statins but not for aspirin and higher than expected prescribing was found for older non-statin cholesterol-lowering agents.

These deficits in medical treatment appear to exist alongside worrying elevations in mortality. Indeed patients with schizophrenia may also have higher rates of post-operative complications (Li et al., 2008) and post-operative mortality (Copeland et al., 2008). However the direction of this relationship is not clearly established from the design of these studies, which are largely observational. Three possible hypotheses link poor medical care and high mortality. Either the poor medical care directly contributes to excess mortality, or a confounding factor indirectly links poor medical care and excess mortality, or the two observations are independent. Even in the latter case, less than average medical care in the face of excess mortality would be concerning. That said Druss et al. (2001) found that mental disorder of all types was associated with a 19% increase in mortality at one year in an unadjusted analysis, but when the five quality indicators were added to the model the association was no longer significant, suggesting that elevated mortality is in fact related to poor quality of care. Is there any wider evidence that links medical care and mortality in mental illness? Several factors may be suggestive. Firstly the types of deaths are often considered avoidable according to the European Community Classification (Amaddeo et al., 2007). Standardized mortality ratios appear to be highest for deaths preventable with adequate health promotion policies. They are also highest in young males, with comorbid alcohol/drug disorder. Elevated rates of poverty, unemployment and lack of insurance (where applicable) are linked with excess mortality and these factors may also hinder these individuals’ access to basic medical services (Saitz et al., 2004; Wells et al., 2002). In those with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C, one group found that ethnicity (being black), gender (male) or living in a community with high exposure to community violence lowered those odds of receiving appropriate care (Swartz et al., 2003). This elevated mortality does not appear to be linked with changes in psychiatric care (Heila et al., 2005). Indeed medical care is linked with medical complications in SMI. For example, Bishop et al. found a low rate of receipt of osteoporosis services along with a greater number of total fractures in women with schizophrenia (Bishop et al., 2004).

Possible explanations for inequalities in care

There are many possible reasons for these apparent deficits in cardiac care for people with mental ill health (Kim et al., 2007). Possibilities include under-recognition, inadequate treatment, poor monitoring and systems issues (Campbell et al., 2002; Palmer, 1997). A much cited factor is lack of healthcare utilization. However, evidence supporting this as the primary explanation for inequality is not entirely clear (Cradock-O’Leary et al., 2002; Dickerson et al., 2003). Folsom et al. (2002) showed that patients with schizophrenia had fewer medical visits and fewer documented medical problems than those with depression. Salsberry et al. (2005) found that, compared with the general population, those with severe mental illness had more emergency department visits, visited a doctor more frequently but, despite this high healthcare utilization, had very low rates of cervical smears and mammograms. Of note is the fact that they also showed that patients with severe mental illness were less likely to have an appointment for general internal medicine in contrast to generally higher rates of visits, suggesting that visits targeted at delivering medical care may be deficient, even in the face of frequent attendance in primary care or emergency departments. In emergency departments they appear less likely to be offered hospital care than other people (Sullivan et al., 2006). Surveys suggest that people with mental ill health (including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder) perceive barriers to accessing primary physical healthcare (Bradford et al., 2008; Crews et al., 1998; Dickerson et al., 2003; Drapalski et al., 2008; Levinson Miller et al., 2003; Zeber et al., 2009). There is accumulating observational evidence to support this belief (Bradford et al., 2008; Chwastiak et al., 2008; Farmer, 1987; Rice and Duncan, 1995). Most commonly this involves availability of medical advice and quality of medical advice (Druss and Rosenheck 1998; Levinson Miller 2003; O’Day et al., 2005). For example, people with psychotic disorders are less likely to have a primary care physician (Bradford et al., 2008). Mental health status has also been linked with poorer GP (general practitioner) attitude and less time spent with the GP (Al-Mandhari et al., 2004).

However, until recently there has been no direct link between primary healthcare and mortality in psychiatry. In an important study Copeland et al. (2009) analysed whether patients’ reduced primary care use over time was a significant predictor of mortality over a four-year period among VHA groups: diabetes only (n = 188,332), schizophrenia only (n = 40,109), and schizophrenia with diabetes (n = 13,025). Patients with schizophrenia only were likely to have low primary care use decreasing with time but most important increasing use was associated with improved survival.

Intervention to improve preventive care

Assuming these disparities are robust, what can be done to improve preventive care and ultimately reduce avoidable deaths in people with mental ill health? Anderson et al. (1998) reported a meta-analysis of 43 studies involving strategies to improve the delivery of preventive care. In general interventions were moderately effective in improving immunization, screening and counselling. Better communication between primary care providers and specialist mental health services could improve screening rates (Miller et al., 2007; Oud et al., 2009; Phelan et al., 2001) and might influence mortality (Crompton et al., 2010). However against this is a lack of consensus as to which healthcare professionals should be responsible for the prevention and management of co-morbid somatic illnesses in SMI patients (Cohn and Sernyak, 2006; Golomb et al., 2000). There is also no culture of ‘beyond routine’ medical care for people with current or past mental ill health. In addition the abilities of psychiatrists to look after physical health of patients is at best underdeveloped (Garden, 2005; Krummel and Kathol, 1987; Mitchell et al., 1998; Phelan and Blair, 2008). For example preventive services are provided on approximately 11% of psychiatric consultations (Daumit et al., 2002). In the UK the Royal College of Psychiatrists have recommended that primary care physicians set up specific clinics for people with mental disorders (The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009). It has also been suggested in the US that a reorganization of mental health services would help redefine responsibility for physical health (Horvitz-Lennon et al., 2006). There is some support for a collaborative model of care, co-locating psychiatric and primary care (Dombrovski and Rosenstock, 2004). In one trial of an integrated model of care for older people, the intervention helped with access but didn’t produce any significant treatment effects for depression or anxiety (Arean et al., 2008). In a second trial a nurse-led intervention increased screening for cardiovascular risk factors by about 30% people with SMI (Osborn et al., 2010). In spite of promising approaches to shared care there is a substantial gap in the routine medical care for many individuals with mental illness or substance use disorders (Knott et al., 2006; Weisner et al., 2001).

In conclusion, there is strong evidence that inequalities in cardiac treatment are disadvantaging those who have schizophrenia and this may be associated with subsequent elevated mortality, although a causative role is not yet established. Nevertheless, it is worrying that deficits in preventive care may prejudice the long-term health of those with mental ill health. Ultimately this may be reflected in higher mortality rates for those given lower frequency or low quality of care. This detrimental effect could be improved by a concerted effort to offer directed enhanced medical care. Currently there is little evidence to support the notion of widespread enhanced medical care for patients with mental illness that is recommended in national guidelines. Future work must focus on organizational changes (healthcare interventions) to increase the quality of medical care and medical treatment for those with schizophrenia and related disorders.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Al-Mandhari AS, Hassan AA, Haran D. (2004) Association between perceived health status and satisfaction with quality of care: Evidence from users of primary health care in Oman. >Fam Pract 21: 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaddeo F, Barbui C, Perini G, Biggeri A, Tansella M. (2007) Avoidable mortality of psychiatric patients in an area with a community-based system of mental health care. >Acta Psychiatr Scand 115: 320–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Janes GR, Jenkins C. (1998) Implementing preventive services: To what extent can we change provider performance in ambulatory care? A review of the screening, immunization, and counselling literature. >Ann Behav Med 20: 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arean PA, Ayalon L, Jin C, et al. (2008) Integrated speciality mental health care among older minorities improves access but not outcomes: Results of the PRISMe study. >Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23: 1086–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo M, Banegas JR, Canas F, et al. (2006) Low level of medical recognition and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with schizophrenia in Spain. >Schizophr Res 81: 176–177 [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JR, Alexander B, Lund BC and Klepser TB. (2004) Osteoporosis screening and treatment in women with schizophrenia: a controlled study. >Pharmacotherapy 24: 515–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford DW, Kim MM, Braxton LE, Marx CE, Butterfield M, Elbogen EB. (2008) Access to medical care among persons with psychotic and major affective disorders. >Psychiatr Serv 59: 847–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. (2002) Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. >Qual Saf Health Care 11: 358–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. (2006) Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: A population-based controlled study. >J Gen Intern Med 21: 1133–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Kazis LE. (2008) Utilization of primary care by veterans with psychiatric illness in the National Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. >J Gen Int Med 23: 1835–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn TA, Sernyak MJ. (2006) Metabolic monitoring for patients treated with antipsychotic medications. >Can J Psychiatry 51: 492–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Pugh MJ, et al. (2008) Postoperative complications in the seriously mentally ill - A systematic review of the literature. >Ann Surg 248: 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Wang CP, et al. (2009) Patterns of primary care and mortality among patients with schizophrenia or diabetes: A cluster analysis approach to the retrospective study of healthcare utilization. >BMC Health Serv Res 9: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cradock-O’Leary J, Young AS, Yano EM, Wang M, Lee ML. (2002) Use of general medical services by VA patients with psychiatric disorders. >Psychiatr Serv 53: 874–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews C, Batal H, Elasy T, et al. (1998) Primary care for those with severe and persistent mental illness. >West J Med 169: 245–250 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton D, Groves A, McGrath J. (2010) What can we do to reduce the burden of avoidable deaths in those with serious mental illness? >Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 19: 4–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, Ford DE. (2002) Receipt of preventive medical services at psychiatric visits by patients with severe mental illness. >Psychiatr Serv 53: 884–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, et al. (2009) Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). >Eur Psychiatry 24: 412–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (1999) National Service Framework for Mental Health. Modern Standards and Service Models London: The Stationery Office [Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. (2002a) Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. >Am J Psych 159: 1584–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB. (2002b) Mental disorders and quality of care among postacute myocardial infarction outpatients. >J Nerv Ment Dis 190: 51–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai MM, Rosenheck RA. (2005) Unmet need for medical care among homeless adults with serious mental illness. >Gen Hosp Psychiatry 27: 418–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, McNary SW, Brown CH, et al. (2003) Somatic healthcare utilization among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. >Med Care 41: 560–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski A, Rosenstock J. (2004) Bridging general medicine and psychiatry: Providing general medical and preventive care for the severely mentally ill. >Curr Opin Psychiatry 17: 523–529 [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Milford J, Goldberg RW, et al. (2008) Perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care among veterans with serious mental illness. >Psychiatr Serv 59: 921–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. (1998) Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. >Am J Psychiatry 155: 1775–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. (2000) Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. >JAMA 283: 506–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. (2001) Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. >Arch Gen Psych 58: 565–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallow S, Bowler C, Dennis M, et al. (1995) Undetected physical illness in older referrals to a community mental-health-service. >Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 10: 74–75 [Google Scholar]

- Farmer S. (1987) Medical problems of chronic patients in a community support program. >Psychiatr Serv 38: 745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felker B, Yazell JJ, Short D. (1996) Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: A review. >Psychiatr Serv 47: 1356–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom DP, McCahill M, Bartels SJ, et al. (2002) Medical comorbidity and receipt of medical care by older homeless people with schizophrenia or depression. >Psychiatr Serv 53: 1456–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garden G. (2005) Physical examination in psychiatric practice. >Adv Psychiatr Treat 11: 142–149 [Google Scholar]

- Golomb BA, Pyne JM, Wright B, Jaworski B, Lohr JB, Bozzette SA. (2000) The role of psychiatrists in primary care of patients with severe mental illness. >Psychiatr Serv 51: 766–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JS, Zhang DD, Ostir GV. (2004) Effect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancer. >J Am Geriatr Soc 52: 106–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heila H, Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J. (2005) Mortality among patients with schizophrenia and reduced psychiatric hospital care. >Psychol Med 35: 725–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heresbach D, Manfredi S, D'halluin PN, Bretagne JF, Branger B. (2006) Review in depth and meta-analysis of controlled trials on colorectal cancer screening by faecal occult blood test. >Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 18: 427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippisley-Cox J, Parker C, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y. (2007) Inequalities in the primary care of patients with coronary heart disease and serious mental health problems: A cross-sectional study. >Heart 93: 1256–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. (2006) From silos to bridges: Meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. >Health Aff 25: 659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LE, Carney CP. (2005) Mental disorders and revascularisation procedures in a commercially insured sample. >Psychosom Med 67: 568–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, et al. (1995) Efficacy of screening mammograph—A metaanalysis. >JAMA 273: 149–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, McCarthy JF, Welsh D, Blow F. (2006) Recognition of co-occurring medical conditions among patients with serious mental illness. >J Nerv Ment Dis 194: 598–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MM, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al. (2007) Healthcare barriers among severely mentally ill homeless adults: Evidence from the five-site health and risk study. >Adm Policy Ment Health 34: 363–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely S, Simon G. (2005) An international study of the effect of physical ill health on psychiatric recovery in primary care. >Psychosom Med 67: 116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely S, Smith M, Lawrence D, Cox M, Campbell LA, Maaten S. (2007) Inequitable access for mentally ill patients to some medically necessary procedures. >CMAJ 176: 779–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott A, Dieperink E, Willenbring ML, et al. (2006) Integrated psychiatric/medical care in a chronic hepatitis C clinic: Effect on antiviral treatment evaluation and outcomes. >Am J Gastroenterol 101: 2254–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koran LM, Sox HC, Marton KI, et al. (1989) Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients. 1. Results in a state mental health system. >Arch Gen Psychiatry 46: 733–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korany E. (1979) Morbidity and rate of undiagnosed physical illness in a psychiatric population. >Arch Gen Psychiatry 36: 414–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummel S, Kathol RG. (1987) What you should know about physical evaluations in psychiatric patients. Results of a survey. >Gen Hosp Psychiatry 9: 275–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Holman CDJ, Jablensky AV, Hobbs MST. (2003) Death rate from ischaemic heart disease in western Australian psychiatric patients 1980–1998. >Br J Psychiatry 182: 31–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson Miller C, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, Rosenheck RA. (2003) Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. >Psychiatr Serv 54: 1158–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Glance LG, Cai X, Mukamel DB. (2007) Are patients with coexisting mental disorders more likely to receive CABG surgery from low-quality cardiac surgeons? The experience in New York State. >Med Care 45: 587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Glance LG, Cai X, Mukamel DB. (2008) Adverse hospital events for mentally-ill patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. >Health Serv Res 43: 2239–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholt JS, Norman P. (2008) Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm reduces overall mortality in men. A meta-analysis of the mid- and long-term effects of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms. >Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 36: 167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord O, Malone D, Mitchell AJ. (2010) Receipt of preventive medical care and medical screening for patients with mental illness: A comparative analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 00 (accessed 1 September 2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackell JA, Harrison DJ, McDonnell DD. (2005) Relationship between preventative physical health care and mental health in individuals with schizophrenia: A survey of caregivers. >Ment Health Serv Res 7: 225–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateen FJ, Jatoi A, Lineberry TW, et al. (2008) Do patients with schizophrenia receive state-of-the-art lung cancer therapy? A brief report Source. >Psychooncology 17: 721–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre JS, Romano J. (1977) Is there a stethoscope in the house (and is it used)? >Arch Gen Psychiatry 34: 1147–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Lasser KE, Becker AE. (2007) Breast and cervical cancer screening for women with mental illness: patient and provider perspectives on improving linkages between primary care and mental health. >Arch Womens Ment Health 10: 189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AC, McCabe EM, Brown KM. (1998) Psychiatrists' attitudes to physical examination of new out-patients with a major depressive disorder. >Psychiatr Bull R Coll Psychiatr 22: 82–84 [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Malone D. (2006) Physical health and schizophrenia. >Curr Opin Psychiatry 19: 432–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Malone D, Carney Doebbeling C. (2009) Quality of medical care for people with and without comorbid mental illness and substance misuse: Systematic review of comparative studies. >Br J Psychiatry 194: 491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2009) Schizophrenia: core interventions in the treatment and management of schizophrenia in adults in primary and secondary care (update). Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG/WaveR/26 [PubMed]

- O’Day B, Killeen MB, Sutton J, Iezzoni LI. (2005) Primary care experiences of people with psychiatric disabilities: Barriers to care and potential solutions. >Psychiatr Rehabil J 28: 339–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn DPJ, Nazareth I, Wright CA, et al. (2010) Impact of a nurse-led intervention to improve screening for cardiovascular risk factors in people with severe mental illnesses. Phase-two cluster randomised feasibility trial of community mental health teams. >BMC Health Serv Res 10: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oud MJT, Schuling J, Slooff CJ, et al. (2009) Care for patients with severe mental illness: The general practitioner's role perspective. >BMC Fam Pract 10: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RH. (1997) Process-based measures of quality: The need for detailed clinical data in large health care databases. >Ann Intern Med 127: 733–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CH. (1978) Psychiatrists and physical examinations: a survey. >Am J Psychiatry 135: 967–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen LA, Normand ST, Drus BG, Rosenheck RA. (2003) Process of care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction for patients with mental illness in the VA health care system: Are there disparities? >Health Serv Res 38: 41–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M, Blair G. (2008) Medical history-taking in psychiatry. >Adv Psychiatric Treat 14: 229–234 [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M, Stradins L, Morrison S. (2001) Physical health of people with severe mental illness. >BMJ 322: 443–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomondon ME, Michael Ho PM, Wang L, et al. (2007) Severe mental illness and mortality of hospitalized ACS patients in the VHA. >BMC Health Serv Res 7: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. (2007) No health without mental health. >Lancet 370: 859–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. (1998) The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. >N Engl J Med 338: 1516–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C, Duncan DF. (1995) Alcohol use and reported physician visits in older adults. >Prev Med 24: 229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists (2009) Occasional Paper 67. Physical Health in Mental Health Available at: htttp://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/collegereports/op/op67.aspx

- Roberts L, Roalfe A, Wilson S, et al. (2007) Physical health care of patients with schizophrenia in primary care: A comparative study. >Fam Pract 24: 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. (2007) A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia—Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? >Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 1123–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Larson M, Horton NJ, Winter M, Samet JH. (2004) Linkage with primary medical care in a prospective cohort of adults with addictions in inpatient detoxification: room for improvement. >Health Serv Res 39: 587–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsberry PJ, Chipps E, Kennedy C. (2005) Use of general medical services among Medicaid patients with severe and persistent mental illness. >Psychiatr Serv 56: 458–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G, Han X, Moore S, Kotrla K. (2006) Disparities in hospitalization for diabetes among persons with and without co-occurring mental disorders. >Psychiatr Serv 57: 1126–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hannon MJ, Bosworth HS, Osher FC, Essock SM, et al. (2003) Regular sources of medical care among persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infection. >Psychiatr Serv 54: 854–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss BG, Katon WJ. (2006) Transforming mental health care at the interface with general medicine: report for the presidents commission. >Psychiatr Serv 57: 37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahia IV, Diwan S, Bankole AO, Kehn M, Nurhussein M, Ramirez P, et al. (2008) Adequacy of medical treatment among older persons with schizophrenia. >Psychiatr Serv 59: 853–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber NS, Cowan DN, Millikan AM, Niebuhr DW. (2009) Psychiatric and general medical conditions comorbid with schizophrenia in the National Hospital Discharge Survey. >Psychiatr Serv 60: 1059–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, et al. (2001) Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment—A randomized controlled trial. >JAMA 286: 1715–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AP, Henderson DC, Weilburg JB, Goff DC, Meigs JB, Cagliero E, et al. (2006) Treatment of cardiac risk factors among patients with schizophrenia and diabetes. >Psychiatr Serv 57: 1145–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Sturm R, Young AS, Burnam MA. (2002) Alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health care for uninsured and insured adults. >Health Serv Res 37: 1055–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J, Foster D. (2000) Cardiovascular procedures in patients with mental disorders. >JAMA 28: 3198–3199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeber JE, Copeland LA, McCarthy JF, Bauer MS, Kilbourne AM. (2009) Perceived access to general medical and psychiatric care among veterans with bipolar disorder. >Am J Public Health 99: 720–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]