Abstract

Owing to equal and increased opportunities for education and employment, today’s trend in Japanese marriages is characterized by late and less frequent marriage. This paper discusses unavoidable diversity in rural families to point out the anticipated consequences of aging in rural areas and to discuss limitations in current public social care policies. Specifically, the averaged proportion of never married and singles at ages 45–49 and 50–54 in legally recognized depopulated cities, towns, and villages in Japan is calculated to illustrate the expected diversity in families in rural depopulated areas. It also illustrates the need for future studies to develop better social care policies for increasing numbers of single caregivers and single elders.

Keywords: family, gender, Japan, rural aging, rural celibacy, social care policy

INTRODUCTION

Rural areas in Japan embody traditional Japan under the ie system, the system of primogeniture legally recognized in the Meiji Civil Code in 1898. Until the late 1960s, young Japanese men and women living in rural areas typically left home at the age of fifteen and went to work. Although subsequent sons were relatively free to lead their lives by their own wills, the eldest son was expected to remain or to return as a successor to take care of his elder parents (Palmer, 1988). Mate selection through love was thought to be immodest. Since activities at school and customary social gatherings were separated by sexes, arranged marriage played an important role (Iwao, 1993). In rural Japan, since jobs in which men engage (farming, fishing, and forestry) are persistently gendered and have seasonality, the trustworthy go-between knowing the two parties greatly contributed to providing ways to look for potential spouses of whom their parents would approve as new members to the ie. Given such a strong ie system, past Japanese social care policy has been underdeveloped, relying on families for elder care, especially through the daughters-in-law.

After the Second World War, the ie system was replaced by the conjugal family system under civil law in 1947. Strongly influenced by Western ideas of liberal democracy, the post-war Constitution was established legally to support individual rather than family orientation in the choice of occupation as well as marriage partner (Wagatsuma & De Vos, 1962; Iwao, 1993). Marriage became a union of equals, and the number of “love matches” began outnumbering arranged marriages (Atoh, 2008). Consequently, arranged marriages that reflect the standpoint of family preference and concern became no longer in favor either in rural or urban areas (Wagatsuma & De Vos, 1962). In addition, equal education and employment opportunities liberated women from traditional gender norms and led to an increase in the postponement of marriage and childbirth, contributing to the dramatic postwar fertility decline. Postwar economic expansion also increased job opportunities in urban areas and urbanization.

Influenced by decreased birth rates, an aging population, and urbanization, rural areas have undergone considerable change. In traditional society, marriage occurred more frequently in rural areas where traditional norms are stronger than urban regions (Kumagai, 2008). However, such trends have changed as younger generations attain higher education and move to cities for education and jobs. In the twenty-first century, marriages occur more frequently in urban regions where a large proportion of young people resides (Kumagai, 2008). At the same time, rural nostalgia documented by ethnographers remains a persistent force to the present day (Knight, 1994). Fifty years ago, before rapid industrialization and urbanization, most care for the aged was exclusively provided for by the family members, and rural areas of Japan have been noted in Western countries for the good care and respect towards elders by family and society (Hirayama & Miyazaki, 1996). Today, despite the dramatic postwar social transformation, social norms of care in rural areas resist changing, and any change is often slow (Tsutsumi, 2001). In the early 1960s, Nakane (1967) discussed families in rural Japan, stating that burden of care was centered on the provision of support by a co-resident daughter-in-law, and such household-centered social insurance for elders remains the major source of care for frail elders today, although increasing numbers of women began expressing their unwillingness to care for in-laws (Traphagan, 2003). Rather than taking on multiple tasks by getting married, having a child, and continuing to have a white-collar career, some middle-class women continue to embrace and reinforce the ideology of their worth as mothers, because care of family members is at least valued as “women’s work” in private; they consider it better than feeling guilty by remaining in the labor force (Boling, 1998; Lock, 1993).

To avoid care dilemma and family obligations, as well as owing to equal and increased opportunities for education and employment for men and women, today’s trend in Japanese marriages is characterized by later and fewer marriages (Retherford, Ogawa, & Matsukura, 2001). In fact, average age for the first marriage increased from 27.2 to 30.1 years old for Japanese men, and 24.4 to 28.3 years old for Japanese women from 1960 to 2007. Accordingly, the lifetime celibacy rate, calculated as the average of the proportions of never-married at ages 45–49 and 50–54, increased from 1.45% to 15.96% for men, and 1.35% to 7.25% for women from 1950 to 2005 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2008). In addition, as many other industrialized countries including the United States experienced over the past 30–40 years, increases in divorce are expected to increase further the number of singles in their 50s. Since only a small proportion of people marry after the age of 45 (less than 2% in 2007) and the proportion of remarriage is also small (less than 3% in 2007) (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2008), a notably high proportion of singles at ages 45 to 55 suggests an unavoidable diversity in families in Japanese society.

The major aim of this paper is to point out such unavoidable diversity in families in rural areas, to point out anticipated consequences of aging in rural depopulated areas, and to discuss limitations in current public social care policies in support of increasing numbers of single caregivers and single elders. Understanding aging in rural depopulated areas is especially important since many of them are geographically remote areas with limited resources, and they provide examples of future aging in rural areas as depopulated areas increase due to fertility and population decline. These depopulated rural areas may also provide a picture for future aging in Japan as not only rural areas continue to lose the young population, but all areas in Japan will soon start to lose the youth due to rapid population decline.

RURAL CELIBACY—UNAVOIDABLE DEMOGRAPHIC REALITY AND PERSISTENT GENDER NORMS

In 2009, there are 497 legally appointed underpopulated cities, towns, and villages according to Article 2 of the Act on Special Measures for Promotion for Independence for Underpopulated Areas (kaso-chiiki jiritsu sokushin tokubetu sochi hou), based on their problematic rate of population decrease.1 Due to recent municipal amalgamation due to rapid population decrease in Japan, the total of 465 underpopulated villages, cities, and towns that appeared on the 2005 census is shown in the figures that follow.

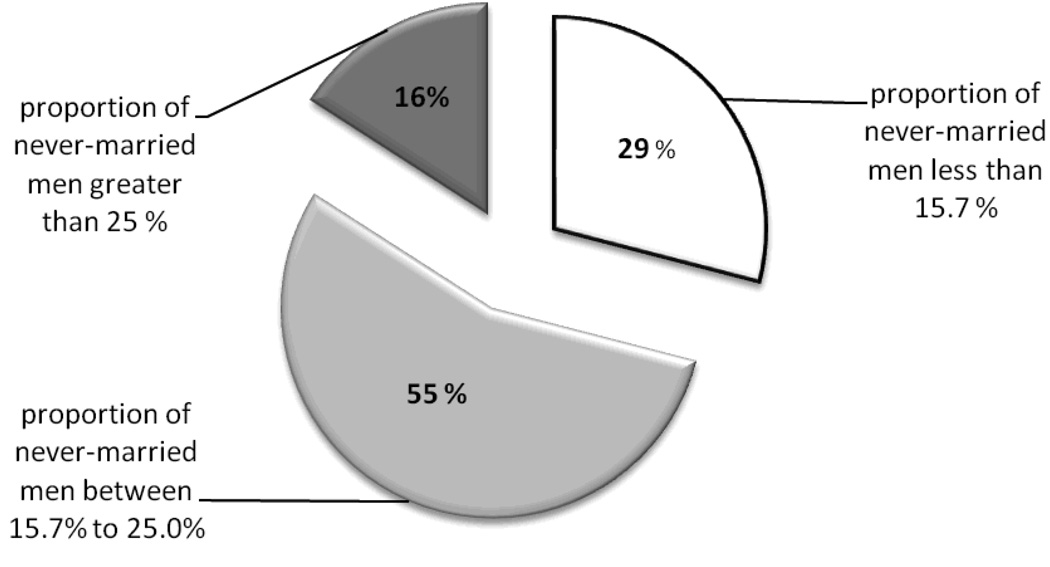

Figure 1 differentiates three averaged proportions of never married Japanese men at ages 45–49 and 50–54 living in 465 depopulated villages, cities, and towns. Great numbers of depopulated areas hold an extremely high proportion of never-married men around 50 years old. They are spread throughout most of the depopulated areas. Since out-of-wedlock births in Japan are not common, at least one in four men around 50 years old in 16% of depopulated areas, and one in six men around 50 years old in 55% of depopulated areas, are never-married and without children (Figure 1). In most depopulated areas across the nation, unavoidably there will be rising proportions of never-married elder men in a couple of decades.

FIGURE 1.

Averaged Proportions of Never-Married Japanese Men at Ages 45–49 and 50–54 Living in 465 Depopulated Areas

In addition, an increasing number of never-married men are expected to become caregivers of their parents. According to a national survey, the proportion of male caregivers increased from 11.2% in 1984 to 22.7% in 2004 (Sugiura, Kutsumi, & Mikami. 2009). Despite the increasing numbers of men taking on what was considered ‘women’s work,” only professionals in clinical practice, social workers, physicians, and home health workers have actually recognized that increasingly men are providing care (Harris & Long, 2000; Sugiura et al., 2009). Since such “women’s work” is unpaid and not highly respected (Chow, 2001), Japanese women continue to take care of their family members, some carrying on a conflict between their traditional roles in the private sphere and increasing employment opportunities in the public sphere (Hashizume, 2000). Because many Japanese women believe that caring is a private, household task that women should take on, it is difficult for women to avoid caregiving responsibilities and to access community resources (Hashizume, 2000). Furthermore, increasing numbers of male caregivers suffer from the stereotypical feminine image of care and its incompatibility with masculine identity. Clearly, gendered traditional norms of care are problematic for all caregivers.

Most previous studies of care focused on the physical and emotional burden on women living with and caring for parents-in-law, not male caregivers. Currently, few studies paid attention to experiences and struggles of older never-married men living with their elder parents. Since Japanese women have been socialized to nurture, Japanese men are rarely respected for becoming caregivers (Long and Harris, 2000; Kasuga, 2001). A man in his 40s was interviewed about his experience as a care provider, and he responded that an old Japanese man once called him a foreigner since Japanese men do not do such “feminine” tasks (Kasuga, 2001). Ignoring experiences and struggles of male caregivers is problematic, especially in rural areas where gendered caregiving norms persist. Depopulated areas present an additional unique problem in aging in rural areas due to the geographical isolation of its residents. In developing social care policies for aging in rural areas, studies of male caregivers are necessary to address this vulnerable and invisible population and the struggles these men are going through due to the clash between the unavoidable demographic reality and persistent gender norms.

Compared with men, fewer depopulated areas have high proportions of never-married Japanese women age 50 or older; in fact, none has a proportion greater than 25%. Such a gender gap in the proportion of never-married around age 50 is strongly influenced by the marriage squeeze, the fluctuation in fertility created by a socially accepted age gap between bride and groom (Haji, 2007; Hodge & Ogawa, 1991). With the dramatic postwar fertility decline, the marriage squeeze has caused a shortfall in the potential number of brides (Hodge & Ogawa, 1991). In Japan, there is a persistent tendency for men to marry younger women, although the gap has narrowed over the decades. In developing nations, such shortfalls in the number of prospective brides can be resolved by men continuing to look for younger brides, which is not a possible case in Japan where improved educational opportunities for women have decreased their likelihood of staying in the depopulated areas as well as getting married in their 20s (Hodge & Ogawa, 1991).

Current limitations in social care policy derive from a lack of comprehensive studies understanding regional diversity; thus, there is no social care policy specifically designed for never-married male caregivers in rural depopulated areas as well as for female caregivers. In developing social care policy, there is an urgent need for future studies to listen to the voices of caregivers beyond the gendered boundaries of care. As Harris and Long (2000) emphasize, “By beginning to understand the day-to-day experience of caregivers and the meanings they assign to that experience, policy makers can move toward designing better policy and programs to support all family caregivers” (p 268).

RURAL SINGLES—UNAVOID ABLE CHALLENGES PRESENTED BY THE GROWING ELDER POPULATION

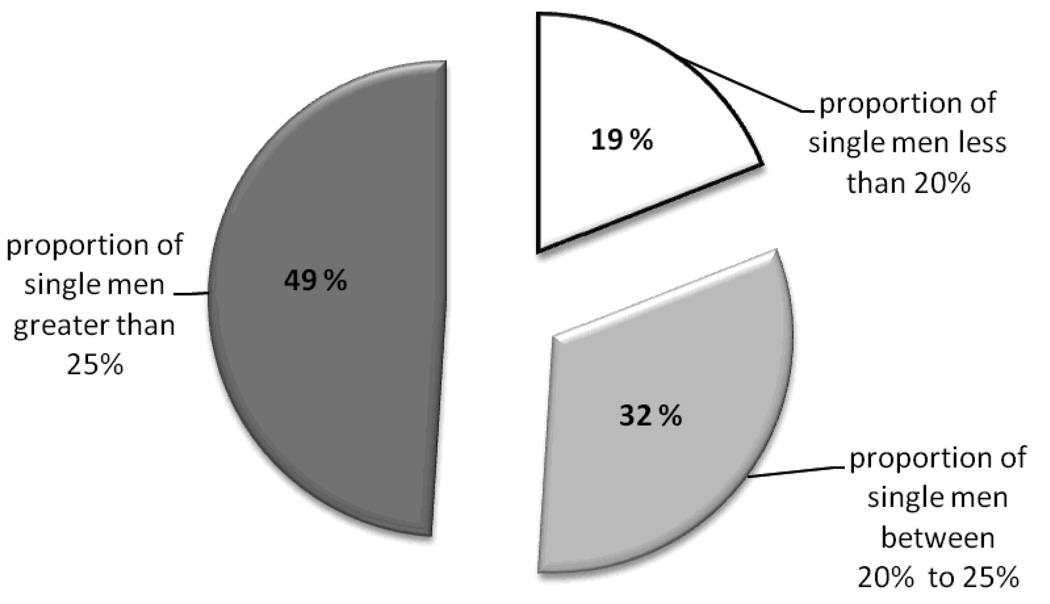

Figure 2 shows three averaged proportions of single men (never-married and divorced) between 45–50 and 50–55 based on Census 2005. Combining the proportion of never-married and divorced men between aged 45–50 and 50–55, at least one in five men is single in greater than 80% of the depopulated areas (Figure 2). Since Japanese women tend to take custody of their children (Fujimura-Fanselow & Kameda, 1994), most of the depopulated areas could face the problem of not being taken care of by family members in the near future.

FIGURE 2.

Averaged Proportions of Single Japanese Men (Never-Married and Divorced) at Ages 45–49 And 50–54 Living in 465 Depopulated Areas

With already increased numbers of elders, both the government and families are already struggling to find care providers. Expecting increasing numbers of single elders in the future, to reduce further physical and financial burden of care, developing social policies to keep single adults healthy is as important as developing social care policies for single elders. A recent study by Yamanaka et al. (2006) found the nutritional differences between middle age and elder Japanese living alone and living with others. They reported higher rates of insufficient intake of protein and green and yellow vegetables for people living alone than those living with others for both genders (Yamanaka, Hirose, Okada, Igata, & Takekawa, 2006). To monitor the well-being of middle-aged single men, it is important for municipal governments, in cooperation with the national government, to develop better social policies to sustain healthy lifestyles in earlier stages before their health conditions deteriorate. For example, occasionally providing free cooking classes aimed at single men and health check-ups. Since care is persistently considered as women’s work, especially in rural areas, developing social policies to keep single, elder men in rural areas healthy and independent is a challenge, but an efficient way to prevent future problems in aging in rural areas.

LIMITATIONS IN CURRENT PUBLIC SOCIAL CARE POLICIES IN RURAL JAPAN

As in the United States, providing adequate and accessible medical and health care services in the rural areas, especially depopulated rural areas, has been a challenge to Japanese government officials, health care providers, and those who need care assistance. While young people can tolerate the inconvenience of traveling long distances, it is not feasible for frail, ill, and disabled elders (Hirayama & Miyazaki, 1996). In addition, unlike urban areas, providing public care services to elders who reside in their homes requires more time and effort for the service providers (Hirayama & Miyazaki, 1996).

To support elders living in rural areas, the Ministry of Health and Welfare has adopted two approaches: 1. Organize and dispatch a team of physicians and nurses close to the villages where there are no available physicians. 2. Establish Kokuho (National Health Insurance) health centers equipped with inpatient beds throughout remote areas of Japan (Hirayama & Miyazaki, 1996). However, due to unexpectedly rapid depopulation and the aging process in rural areas, many rural areas face greater challenges in managing these centers, especially with a lack of doctors and nurses.

As much state and public provision for care was inadequate to keep pace with a rapidly aging population, families continue to take great responsibility for eldercare. Initially, the Japanese government attempted to establish a European-style welfare state in the 1970s. However, in the 1980s, facing a steeply rising burden of taxes plus social security contributions, the government scaled back the scheme to build a Japanese welfare policy in which the government can seek to shift some of the burden of caring back to families and to elders themselves rather than institutionalized care (Boling, 1998; Ogawa & Retherford, 1997). Japanese policymakers argued that it was unnecessary to establish a Western style welfare system given the “male breadwinner” family system where men’s earnings were sufficient to allow women to take domestic tasks including elder care (Tokoro, 2009).

To address a rapidly aging population, the government announced its Gold Plan in 1990 to improve welfare services including long-term care facilities and home help services (day care, day health services, home nursing and rehabilitation, short stays in inpatient facilities), attempting to reduce the burden of family care. The plan was later revised to expand these services (Hashizume, 2000; Kolanowski, 1997). In April 2000, long-term care insurance (LTCI) for elders was initiated by the national government to provide locally administered home care and institutional services. These government supported services were established because the lack of nursing homes was driving more elders to use regular hospitals for extended care (Kasza, 2006). However, due to the rapidly and ever-increasing number of elders, increasing demand for services is much greater than what both institutional and home care services can supply (Ogawa & Retherford 1997). In fact, the number of elders in need of long-term care was estimated to be 5.4 million in 2005 compared to 2.8 million in 2000 (Anesaki, 2008). Although the current Japanese social care system is trying to set a new balance between the family and the state, it continues to keep the family heavily involved in the care of older people due to limited availability of public facilities and care providers to meet the needs for ever increasing numbers of Japanese elders.

In 2004, over 75% of care for elders who need assistance was provided by family members, mostly by children living together. Among elders who need assistance living with at least one child, 7.6% of their caregivers are sons compared to 11.2% who are provided care by their daughters. Husbands made up 8.5% of caregivers, and wives, 16.5%. To support any policy emphasis on community care, family members continue to take major roles in the past and present Japanese social care policy (Tokoro, 2009). Such a family-oriented social care system is not only problematic for female caregivers, whose lives are constrained by care expectations and obligations, but also problematic for male caregivers who continue to be unrecognized in public.

In Japan, people still value their privacy and many feel embarrassed in asking public services for support. Family caregivers are sometimes reluctant to use formal health, social, and nursing services (Asahara, Momose, Murashima, Okubo, & Magilvy, 2001; Hashizume, 2000). Asahara and colleagues (2001) claimed that sekentei, social appearance regarding how people or neighbors think of him or her if family members do not take major responsibility for taking care of their elder parents, was significantly correlated with care burden. Caregiving as a very personal matter as well as a strong sekentei in rural communities often results in underutilization of social services (Asai & Kameoka, 2005). Such concern toward sekentei is expected to be much stronger in rural areas than in urban areas, where families tend to live in closely-tied communities. Thus, there may be more single caregivers in rural areas, especially single male caregivers, invisible in society but desperately needing support for both physical and mental care of their parents. If they worry about sekentei, they may be unable to seek help even if they need to. The pitfall of family-oriented social care policy becomes more visible as we study aging in rural Japan.

In Japan, rural elders live longer than the urban elders, but the urban elders enjoy a longer duration of being free from physical disabilities than rural elders (Ogawa, 2004). This is partly because urban elders are more likely to be influenced by institutional factors such as retirement age since they are more likely to be in a highly organized labor market than are rural elders (Ogawa, 2004). Urban elders are more likely to retire before their health deteriorates and may have more time to detect and recover from their health problems in early stages by going to see doctors than do rural elders. Another reason could be differences in the types of jobs elders hold in rural areas versus urban areas. Rural elders tend to be involved in jobs related to agriculture, forestry, or fishing than urban elders, and these jobs not only encourage rural elders to work until their health deteriorates, they also may increase their risk of musculoskeletal injuries.

Because urban elders are more likely to belong to highly organized labor markets and are more likely to receive second-tier payments than rural elders, urban elders are more likely to retire early before their health conditions deteriorate. Japan began a universal health insurance system and the distribution of pensions beginning in April 1961; thus, all Japanese citizens receive pensions. There are three types of pensions: 1. a national pension (kokumin nenkin) for the self-employed; 2. employee pensions (kosei nenkin) for salaried persons; and 3. mutual aid pensions (kyosai nenkin) for civil servants (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2009). In 1986, a two-tier pension system was established and the entire population is eligible to receive a national pension, to which employees' pensions and mutual aid pensions are added for people who are eligible (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2009). Thus, although rural nostalgia often depicts rural elders to be happier than urban elders surrounded by their family members, rural elders can be more socially vulnerable than urban elders, especially if they do not have siblings, spouses, or children.

In developing social care policies for aging in rural areas, policymakers need to consider improving the social care system for single caregivers, especially single male caregivers, as well as preparing for a better social care system for the increasing numbers of single elders. Gender-responsive rather than gender-neutral social care policy that empowers men as well as women caregivers is necessary (Harris & Long, 2000). In addition, policymakers should pay great attention to the social vulnerability of rural elder singles and rural single caregivers, since they are less likely to monitor their health conditions due to their occupations and pension systems, and they are less likely to use public services concerning sekentei, in addition to the shortage of hospitals, doctors, and nurses due to their remote locations.

DISCUSSION

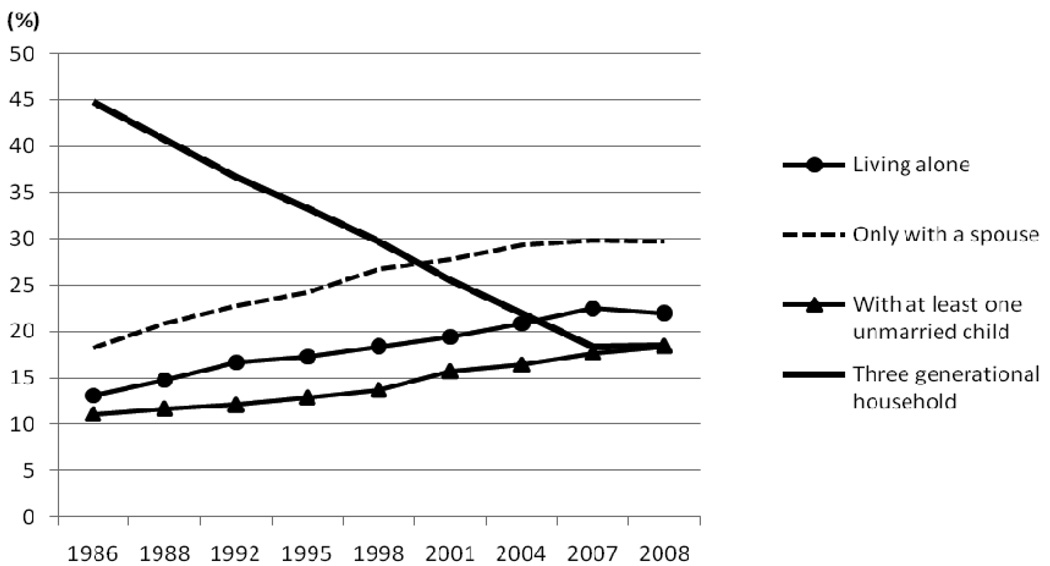

Over the past few decades, three-generation households have decreased steadily while other types of households with elders ages 65 and older have increased gradually (Figure 3). Now there are more elders living alone or living only with a spouse than elders living in three-generational households, and the proportion of elders living with at least one unmarried child reached almost the same level as elders living in three-generational households (Figure 3). Reflecting a rapidly growing diversity of elder households, social care policies need to be revised more frequently rather than continuing to rely on spouses and children as it used to be when the majority of elders lived in three-generational households.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in Types of Households that Include the Elderly 65 Years Old and Older. Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Basic Survey of National Life, 2008. Note: 1995 date excludes Hyogo Prefecture.

Traditional family norms change rapidly in urban areas, accommodating the needs of a large proportion of the younger generation. By contrast, it appears that traditional family norms will slowly but inevitably change in depopulated rural areas as a consequence of demographic reality. Aikawa (2002) claims that some parents in rural villages started to live separately from their sons, so that they have a less difficult time finding a bride. In a couple of decades, it is possible that rural families may diversify more rapidly than urban families since a rising proportion of elder singles in depopulated areas may decide to live alone, with their parents, with their cohabitating partner, with their siblings, or with their children from a previous marriage. Social care policies for rural elders should consider such diversity rather than rely on rural nostalgia.

Aging in urban areas has its own unique problem as well, although this paper focused on aging in rural areas. Sankei News reported on September 11, 2008, that half of 2,300 households of Toyama-danchi, one of the multi-unit apartments in Shinjuku managed by the Tokyo Metropolitan government, were 65 years and older. About 60% of them were elders above 75 years old living alone. Cataclysmic events such as earthquakes or fire can happen anywhere, and urban elders living alone without a closely-knit community are vulnerable to these problems.

Social care policy designed for never-married rural singles will not only alleviate the care burden for their parents and promote the well-being of those single caregivers as they become elders; such policy will also improve social care policies for all caregivers based on their voices and experiences.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship to the first author from the National Institute on Aging (T32 AG00129) through the Center for Demography of Health and Aging (P30 AG17266) and the Center for Demography and Ecology (R24 HD047873). We would like to thank Jamison T. Arimoto, Esq., for useful insights.

Footnotes

Specifically, these villages, cities, and towns fall under one of the following cases in addition to the financial capability index (See Kurihara 2007 for an explanation of the index) less than .42: (1) the rate of population decrease greater than 30% between 1960 and 1995; (2) the rate of population decrease greater than 25% between 1960 and 1995 in addition to the proportion of the elderly (65 and above) greater than 24% in 1995; (3) the rate of population decrease greater than 25% between 1960 and 1995 in addition to the proportion of the youth (ages 15 to 29) less than 15% in 1995 (In the first three cases of population decrease, if the population decrease has recovered at least by 10% between 1970 and 1995, these cities, villages, and towns will not be considered); or (4) the rate of population decrease greater than 19% between 1970 and 1995.

Contributor Information

Kimiko Tanaka, Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, New York, USA.

Miho Iwasawa, Senior Researcher, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- Aikawa Y. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries; Nōson no mikon bankonka to oyako nisedai fūfubekkyo no genjō (Late and less marriage in rural villages and changes in family structure) 2002 available online at http://www.maff.go.jp/primaff/koho/seika/review/pdf/primaffreview2002-7-28.pdf (in Japanese, retrieved on June 16, 2009).

- Anesaki M. History of Public Health in Modern Japan: The road to becoming the healthiest nation in the world. In: Lewis MJ, MacPherson KL, editors. Public health in Asia and the Pacific: historical and comparative perspectives. New York: Routledge: 2008. pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Asahara K, Momose Y, Murashima S, Okubo N, Magilvy JK. The Relationship of Social Norms to Use of Services and Caregiver Burden in Japan. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33(4):375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai MO, Kameoka VA. The Influence of Sekentei on Family Caregiving and Underutilization of Social Services among Japanese Caregivers. Social Work. 2005;50(2):111–118. doi: 10.1093/sw/50.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atoh M. Family Changes in the Context of Lowest-Low Fertility: The Case of Japan. International Journal of Japanese Sociology. 2008;17(1):14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Boling P. Family Policy in Japan. Journal of Social Policy. 1998;27(2):173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chow E. Transforming Gender and Development in East Asia. New York: Routledge: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura-Fanselow K, Kameda A. Japanese Women: New Feminist Perspectives on the Past, Present, and Future. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haji K. NLI Research Institute; Danjo-hi ga semaru shakai-seido no henkou (Expected changes in social systems faced by sex imbalance in population structure) 2007 available online at: http://www.nli-research.co.jp/report/econo_eye/2007/nn070702.html (in Japanese, retrieved on March 27, 2009).

- Harris PB, Long SO. Recognizing the need for gender-responsive family caregiving policy. In: Long SO, editor. Caring for the Elderly in Japan and the U.S. New York: Routledge: 2000. pp. 248–271. [Google Scholar]

- Hashizume Y. Gender issues and Japanese family-centered caregiving for frail elderly parents or parents-in-law in modern Japan: From the sociocultural and historical perspectives. Public Health Nursing. 2000;17(1):25–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama H, Miyazaki A. Implementing Public Policies and Services in Rural Japan: Issues and Problems. Journal of Aging and Social Policy. 1996;8(2):133–146. doi: 10.1300/J031v08n02_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge RW, Ogawa N. Fertility Change in Contemporary Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Iwao S. The Japanese Woman. New York: The Free Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga K. Kaigomondai no Shakaigaku (Sociological analysis of care issues) Iwanami, Tokyo Japan: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kasza G. One World of Welfare: Japan in Comparative Perspective. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Knight J. Town-Making in Rural Japan: An Example from Wakayama. Journal of Rural Studies. 1994;10(3):249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski RJ. Japan’s Gold Plan Emphasizes Home Care and the Consumer. CARING Magazine. 1997:38–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai F. Families in Japan; Changes, Continuities, and Regional Variations. Lanham: University Press of America; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara J. Demystifying Japan’s Economic Recovery. Business Economics. 2007;42(3):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lock M. Ideology, female midlife, and the graying of Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies. 1993;19(1):43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Social Security System: An Aging Society and Its Impact on Social Security. Japan Fact Sheet. 2009 available online at http://web-japan.org/factsheet/en/pdf/e42_security.pdf (retrieved on June 13, 2009).

- Nakane C. Kinship and Economic Organization in Rural Japan. Longon: The Athlone Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (NIPSSR) NIPSSR; Population Statistics of Japan 2009. 2008 available online at http://www.ipss.go.jp (in Japanese, retrieved on March 27, 2009).

- Ogawa N. Urban-Rural Differentials in Health Conditions and Labor Force Participation among the Japanese Elderly. Geriatrics and Gerontology International 4. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa N, Retherford RD. Shifting Costs of Caring for the Elderly Back to Families in Japan: Will It Work? Population and Development Review. 1997;23(1):59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer E. Planned Relocation of Severely Depopulated Rural Settlements: a Case Study from Japan. Journal of Rural Studies. 1988;4(1):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Retherford R, Ogawa N, Matsukura R. Late Marriage and Less Marriage in Japan. Population and Development Review. 2004;27(1):65–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sankei Newspaper. Shinjyuku ni "Genkai Shuraku" shutsugen "Toshin no ubasute-yama", 65sai ijou ga hansuu no danchi shutsugen (Multi-unit Apartment in Shinjuku Reaching a Critical Limit in the Number of Elderly). September 7, 2008. Tokyo: Sankei Shinbun & Sankei Digital; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura K, Ito M, Kutsumi M, Mikami H. Gender Differences in Spousal Caregiving in Japan. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;64B(1):147–156. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokoro M. Ageing in Japan: Family changes and policy developments. In: Fu T, Hughes R, editors. Ageing in East Asia: Challenges and policies for the twenty-first century. New York: Routledge: 2009. pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Traphagan W. Contesting Coresidence: Women, In-laws, and Health Care in Rural Japan. In: Traphagan W, Knight J, editors. Demographic Change and the Family in Japan’s Aging Society. New York: State University of New York Press; 2003. pp. 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi M. Succession of Stem Families in Rural Japan: Cases in Yamanashi Prefecture. International Journal of Japanese Sociology. 2001;10:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wagatsuma H, De Vos G. Attitudes Toward Arranged Marriage in Rural Japan. Human Organization. 1962;21:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K, Hirose A, Okada K, Igata A, Takekawa R. Nutritional Differences between Middle Age and Elderly People Living Alone and Living with Others. Nagoya University of Arts and Sciences Research Bulletin 2. 2006 available online at http://library.nakanishi.ac.jp/kiyou/gakugei(2)/06.pdf (in Japanese, retrieved on June 14, 2009). [Google Scholar]