Introduction

Lidocaine is used for regional anesthesia as an antiarrhythmic drug, and as an analgesic for various painful conditions, in particular, disorders associated with hypersensitivity, such as fibromyalgia,1 neuropathic pain conditions,2 and as adjuvant medication for the treatment of postoperative pain associated with abdominal surgery.3-5 Preclinical models of neuropathic 6 and deep tissue (colon7, bladder8) pains have demonstrated clear inhibitory effects of intravenous lidocaine but lesser effects have been noted in cutaneous pain models.9 An intriguing body of evidence suggests that short-term administration of intravenous lidocaine may produce pain relief that far exceeds both the duration of infusion and the half-life of the drug.6 The older clinical literature even supports the use of lidocaine as an analgesic supplement to general anesthesia.10,11

Despite this wealth of clinical and preclinical literature, experimental evoked pain studies have had equivocal results related to the analgesic effects of intravenous lidocaine.12 A possible explanation for this incongruity between experimental and clinical pain measures is that the source of pain generation differs between the varying conditions. Experimental pain measures most commonly assess superficial cutaneous sensation, whereas most clinical pain states such as post-operative pain have deep tissue components. Comparisons of preclinical experimental measures suggest that deep tissue-associated nociceptive neurons may have greater susceptibility to the inhibitory effects of intravenous lidocaine.7-9 Therefore, to test whether a similar effect of intravenous lidocaine can be seen in human volunteers, we extended our investigation from superficial stimuli to muscle ischemia, a validated model of deep tissue pain.13,14 In this way, we were able to make a comparison of the effects of the drug on the two types of stimuli. Our hypothesis was that lidocaine, administered as short intravenous infusion, would have a selective analgesic effect on deep tissue pain in healthy volunteers.

Methods

Overview

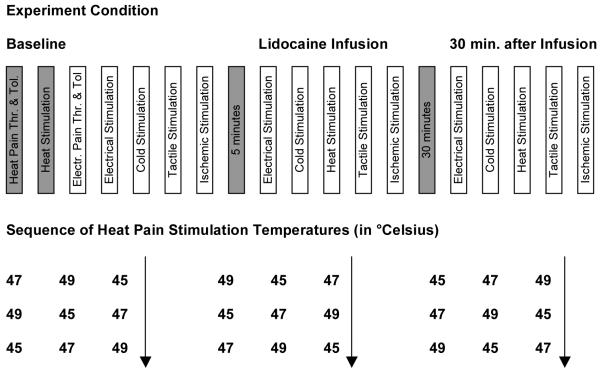

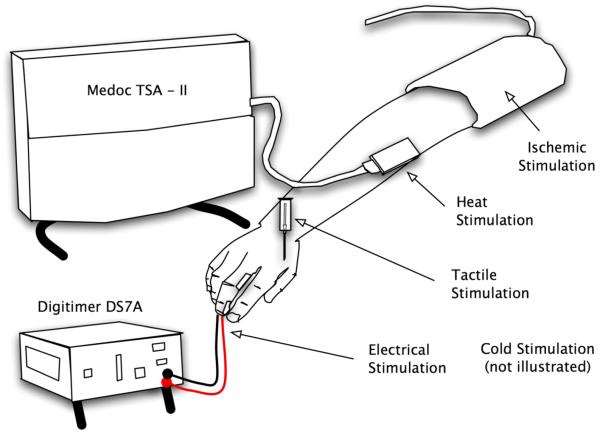

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama and volunteers consented in writing to participate in this study. At a screening visit, participants with a significant history of pulmonary, cardiovascular, neurological, or pain condition were excluded. Further exclusion criteria were pregnancy, chronic pain or the chronic use of analgesic medications, a body mass index of greater than 35 kg/m2 or a history of sensitivity to lidocaine. During the study visit, participants received left antecubital intravenous access for the administration of the drug. Vital signs were recorded at baseline and every five minutes during and after the lidocaine infusion. Measurements included pulse oximetry, blood pressure, heart rate and electrocardiogram. Participants received several experimental pain stimuli and a pinprick test to evaluate normal sensation as illustrated in figure 1 and 2. This sequence of stimuli was presented at baseline, during a 20-minute infusion with lidocaine and while receiving a saline infusion, 30 minutes after discontinuation of lidocaine (figure 1).

Figure 1. Experiment Design.

Illustration of the experiment pain testing sequence for a participant. Heat Pain Threshold and Tolerance were obtained at baseline only. The sequence of heat pain temperatures is shown in the lower section. Note that there was a 30 minute interval between Lidocaine infusion stop and repeated testing. Thr. … Threshold, Tol. … Tolerance, Electr. … Electrical.

Figure 2. Pain and Sensory Tasks.

This Illustration of Sensory and Pain Tasks shows the 3 by 3 inch probe attached to the TSA-II base unit (Medoc, Haifa, Israel) which was used to administer painful heat stimuli to the forearm, the tourniquet used to interrupt arterial blood flow to the arm as part of the ischemic procedure, the electrodes applied to the middle finger and attached to the direct current DS7A nerve stimulator (Digitimer, Hertfordshire, England) and a 10 mL plastic syringe barrel through which a 23-gauge needle attached to a tuberculin (TB) needle barrel was inserted for the testing of normal pin prick sensation at the hand.

Lidocaine Administration

Lidocaine was delivered using a computer-assisted infusion (CAI) controlled by the program Stanpump,15 approved by the FDA under the investigational device exemption FDA G060183. We chose a plasma concentration of 2 μg/mL as effect site concentration for lidocaine based a study by Wallace and collaborators.16 Pharmacokinetic parameters were adjusted based on height, age, gender and weight. The total dose administered was approximately 2 mg/kg. Participants were told that they, would receive a saline or a lidocaine infusion, but were blinded to the order of the infusion. Investigators were not blinded to the order of the infusion.

Pain and Sensory Procedures

Thermal Pain Procedure

The thermal procedure involved a baseline assessment of heat pain threshold and tolerance. Contact heat stimuli were delivered using a computer-controlled Medoc Thermal Sensory Analyzer (TSA-II; Ramat Yishai, Israel), which is a peltier element-based stimulator. Temperature levels were monitored by a thermistor and returned to a preset baseline of 32°C by active cooling at a rate of 10°C/s. The 3 × 3 cm contact probe was applied to the right forearm. In a separate series of trials, heat pain tolerances were assessed using an ascending method of limits. From a baseline of 32°C, the probe temperature was increased at a rate of 1°C/s until the participant responded by pressing a button to indicate when he or she first perceived the stimulus as painful and when he or she no longer felt able to tolerate the pain. Three trials of heat pain threshold (HPTh) and heat pain tolerance (HPTo) were presented to each participant. The position of the thermode was altered slightly between trials (although it remained on the ventral forearm) to avoid either sensitization or response suppression of cutaneous heat nociceptors. For each measure, the average of all three trials was computed for use in subsequent analyses.

To determine suprathreshold thermal pain ratings, participants received three individual thermal stimuli of two-second duration and were asked to rate their perceived pain intensity using a mechanical slide algometer immediately after each stimulus. The three heat pain temperatures for this procedure were calculated such that they would be distributed equidistant within the individual’s HPTh and HPTo. Each of the three heat pain stimuli were presented three times and balanced in order using a Graeco-Latin square design.

Electrical Pain Procedure

Similar to the heat pain measurements, the electrical procedure involved a baseline assessment of electrical pain threshold and tolerance. Peripheral nerve stimulation electrodes were attached to the base and the tip of the third digit and connected to a constant current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer Ltd, Hertfordshire, England). Ascending electrical stimuli of 2000 ◻s duration, ranging from 0.5 to 35 mA (max.) intensity was administered one per second in 0.5 mA increments. Participants were instructed to indicate when they first felt the slightest sense of pain (electrical pain threshold, EPTh) and when they were unable to tolerate a further increase (electrical pain tolerance, EPTo). For each measure, the average of three trials was computed for use in subsequent analyses. Each of the three electrical pain stimuli were presented three times and balanced in order using a Graeco-Latin square design (Figure 1).

Ischemic Pain Procedure

The right arm was exsanguinated by elevating it above heart level for 30 seconds, after which the arm was occluded with a standard blood pressure cuff positioned proximal to the elbow inflated to twice the participant’s mean arterial pressure. Participants then performed 20 handgrip exercises of 2-second duration at 4-second intervals at 50% of their maximum grip strength. Participants were instructed to rate their pain every thirty seconds and when the pain became intolerable.

Cold Pain Procedure

The participant’s foot was immersed up to the ankle into a container filled with ice water of 3°C. Participants were instructed to maintain their foot in the container until the cold pain became intolerable (cold pain tolerance). The length of time was recorded in seconds. This procedure was repeated once with a gap of at least fifteen minutes in-between repeated tests.

Testing of Normal Sensation

Pin prick sensory thresholds (PPT) were obtained by touching the skin in-between the first and second metacarpal bone with a 23-gauge needles which moved freely out of a 10 mL plastic syringe barrel. The pin prick sensation was modified by adding small weights to the 23-gauge needles (from 0.2 to 5.2 gm). We used the syringe barrel of tuberculin (TB) needles that were cut to different lengths to add the desired weight to the 23-gauge needle. The PPT was determined using the weighted 23-gauge needle in ascending order, according to the method of limits. 17 In this procedure, we were evaluating whether participants were able to feel the touch of the needle. The participant’s arm was placed on a tray table. A linen sheet was suspended in-between two IV poles in such a fashion that the subject’s view of his/her hand was blocked.

Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

The sample size analysis was based on a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance assuming independent multivariate normal distributions of pain scores at three levels (baseline, during lidocaine infusion, after lidocaine infusion). We used the results of a previous study where we observed differences in pain ratings associated with propofol sedation18 as a guide for our assumptions for the expected difference and variability in visual analogue scores (VAS) of pain. We assumed a common correlation coefficient (of the correlation matrix) of 0.3, a within the subject standard deviation of pain scores of 1.5 (0-10). In order to detect a minimum difference of mean pain ratings of .65 (0-10) using a significance level of ◻= 0.05 and a power of 80%, we calculated that a minimal required sample size of 14 participants (StudySize, ver2.0.4, SAS version 7.1, proc power) was needed.

The analysis was performed using a mixed model using the residual maximum likelihood method (REML) with the software JMP 7 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Drug conditions, ‘baseline’, ‘during lidocaine infusion’ and ‘after lidocaine infusion’, were considered fixed effects and participants were entered as random effects. When an overall significant difference was detected for a particular pain procedure, we compared the least squares (LS) means across conditions using an unadjusted t-test. This analysis procedure was used for each pain or sensory modality.

Results

The volunteers were of six male and ten female, eight Caucasian and eight African-American participants.

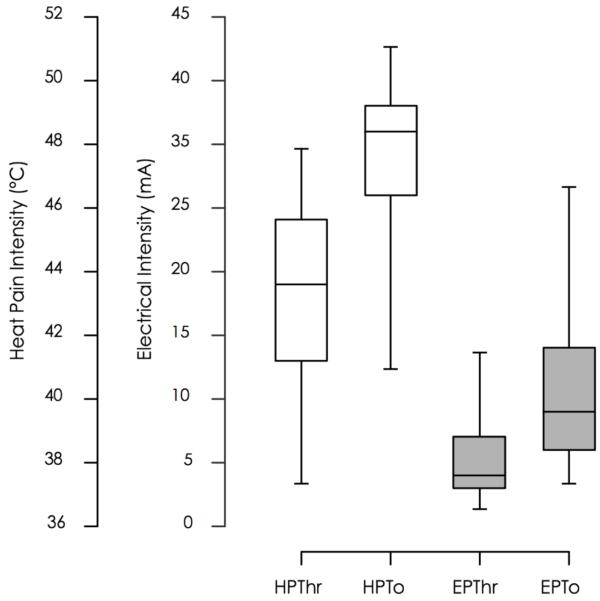

We found a significant difference in the least square (LS) means of pain ratings for the ischemic pain procedure (p < 0.001) across conditions (figure 3). The LS means and standard error (SE) for baseline pain visual analogue scale (VAS) ratings were 4.3 ± 0.5 at baseline and decreased to 3.5 ± 0.5 during a computer assisted lidocaine infusion and 3.4 ± 0.5 thirty minutes after discontinuation of the lidocaine infusion. Ratings during and after lidocaine infusion were statistically significant lower when compared to baseline (Table 1a).

Figure 3. LS Means Plot of Pain Ratings.

This graph shows the least square (LS) means and errors of the ischemic (deep pain) and heat pain (superficial pain) tasks. The y-axis display the response units, visual analogue scores (VAS) of pain and the x-axis represents the study conditions, baseline, during lidocaine administration and during a saline infusion, 30 minutes after discontinuation of lidocaine. LS means pairs that are significantly different are marked with an asterisk or a plus sign.

Table 1.

Mean Pain Ratings are provided as VAS scores; range [0,10]. Cold Pain Mean Ratings are provided as seconds; range : [0,120]

| a P-values for Comparisons Across Conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lidocaine vs | Baseline vs | Lidocaine vs | |

| Modality | Baseline | After Lidocaine | After Lidocaine |

| Cold Pain | 0.076 | 0.065 | 0.903 |

| Electrical Pain | 0.072 | 0.541 | 0.016 |

| Heat Pain | 0.417 | 0.403 | 0.980 |

| Ischemic Pain | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.820 |

| Tactile | 0.214 | 0.347 | 0.380 |

| b Pain Ratings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | p-value | LS Means | ||

| Baseline | Infusion | After Lidocaine | ||

| Cold Pain (sec) | 0.110 | 42.080 | 50.610 | 51.21 |

| Electrical Pain (VAS) | 0.044 | 2.400 | 2.040 | 2.52 |

| Heat Pain (VAS) | 0.636 | 3.010 | 2.830 | 2.82 |

| Ischemic Pain | <.001 | 4.31 | 3.49 | 3.44 |

| Tactile (weight in gm) | 0.430 | 0.283 | 0.267 | 0.271 |

P-values less than 0.05 are bold-faced. The p-values in table 1.b. are the results of the main effects (F-tests) whereas p-values in table 1.a. represent the pairwise comparisons across conditions (t-tests).

Using the electrical pain model, we also observed a significant overall difference of LS means of pain ratings (p=0.044). The comparison of baseline ratings versus ratings during lidocaine infusion was close to significant (p = 0.072) and a significant difference comparing ratings during lidocaine infusion to those obtained thirty minutes after discontinuation of the infusion (p = 0.016).

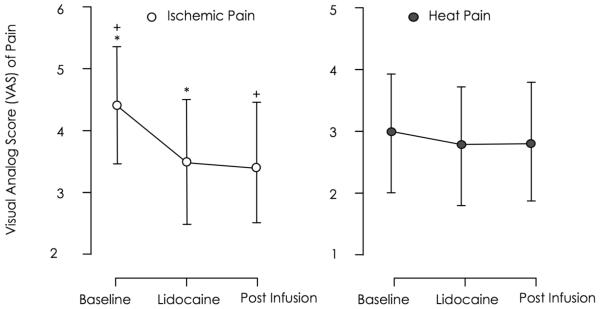

We did not observe a significant change of pain measures when comparing the cold pain tolerance times, the tactile threshold and the heat pain VAS ratings (table 1b). Individual baseline heat pain and electrical pain ratings are displayed in Figure 4. The interquartile range was [41.5, 45.8 °C] for HPTh, [47.6, 49.0 °C] for HPTo, [2.5, 6.4 mA] for EPTh and [6.3, 14.4 mA] for EPTo.

Figure 4. Baseline Heat Pain and Electrical Pain Threshold and Tolerance.

This graph shows percentile box plots of heat and electrical threshold and tolerance measures. The left y-axis displays the degrees Celcius, the response units of the heat task and the right y-axis displays milliampere, the response units of the electrical task. The x-axis shows the test categories, heat pain threshold and tolerance and electrical pain threshold and tolerance. The boxes represent the 25th, median and 75th percentile. Whisker bars represent the 5th and 95th percentile.

Discussion

The most important finding of the our study was that intravenous lidocaine produced a selective inhibitory effect on deep ischemic pain but not on superficial cutaneous pain modalities (heat, cold, electrical) or tactile sensation. We found that intravenous lidocaine had a statistically significant and sustained analgesic effect on ischemic pain provoked by the tourniquet technique but little or no effect on other measures except for a temporary effect on electrical pain, limited to the duration of the infusion (table 1, figure 3).

There are important clinical implications to these results. They explain the incongruities that have been noted between experimental pain models and clinical analgesic effects by revealing that there is an importance to the modality of the stimulus generation. The observed sustained analgesic effect of systemic lidocaine in the ischemic pain model suggests that lidocaine may be particularly useful in the treatment of deep pain but of limited value for superficial pains except in neuropathic conditions. Most types of post-surgical pain have both a deep and an ischemic component because the surgical incision includes deep tissues and often interrupts the local vascular supply. For this reason some investigators argue that the ischemic pain model, which has been extensively used to validate the pharmacologic effect of analgesic medications, may be best suited to simulate clinical pain.14 The origin of ischemic pain is the muscle where cytokines, triggered by depletion of cellular energy sources, cause stimulation of nociceptors and in turn increased signal transmission of Aδ and C fibers. 19 With respect to its neurobiology, ischemic pain better represents surgical pain originating from muscle, bone or internal organs.

We also noted a temporary analgesic effect on electrical pain, which is the result of the direct stimulation of cutaneous nociceptors and did not observe a significant analgesic effect in the thermal pain modalities; heat and cold pain. The temporary suppression of pain perception may be attributable to a direct effect of circulating lidocaine which has been shown to reduce neuronal activity emanating from neuromas.20 This pain model has not been used as widely for psychometric studies and there probably exists a greater amount of literature on the paradoxical analgesic effect of transcutaneous direct neuronal electrical stimulation.21,22 While the shock-like, stinging quality of electrical pain is rarely observed in the clinical context, this modality is of interest because this modality has shown to be very useful in the study of neuronal processing of pain using neuroimaging techniques.23

We suggest that our observation of a temporary analgesic effect of lidocaine in contrast to the more sustained effect on ischemic pain is consistent with the existing literature about the clinical use of lidocaine to treat different forms of chronic pain.24 Any analgesic effect during the infusion of lidocaine can probably be explained by the direct pharmacodynamic drug effect mediated through its action of the fast voltage gated sodium channels in the cell membrane. This direct lidocaine effect may be dependent on the available plasma concentration of the drug. The concentration and mode of delivery in our study was based on a report by Wallace et al25 who evaluated the effect of systemic lidocaine on neuropathic pain using a computer assisted infusion (CAI) with a target plasma concentration ranging from 0.5 μg/ml to 2.5 μg/ml. To achieve an effective dose while minimizing potential side effects, we chose a plasma concentration of 2.0 μg/ml. We did not observe any side effects other than a mild sensation of lightheadedness similar to what was observed by Wallace.

In this study we also wanted to address the question whether lidocaine may have an effect on pin prick sensation. Many investigators limit the assessment of analgesic efficacy of a drug to the study of clinical or experimental pain without evaluating whether a compound or intervention might affect normal sensation. However, the complexity and variability of painful conditions such as fibromyalgia or complex regional pain syndrome has led investigators to apply a more comprehensive approach to quantitative sensory testing that includes quantification of normal sensation. 26 It is conceivable that systemic lidocaine lowers the threshold for normal sensation. We examined this possibility using pin prick sensory thresholds (PPT) applying weighted 23-gauge needles in a subject blinded fashion but did not find that lidocaine treatment had any effect on the required weight to illicit a pin prick sensation. We therefore conclude that systemic lidocaine at a plasma concentration of 2.0 μg/ml does not alter normal sensation.

When interpreting the results of our study, we should point out that our data, obtained from healthy volunteers using experimental pain models, might not necessarily predict the effects of Lidocaine in the clinical setting. Patients suffering from painful conditions are a very heterogeneous group with potentially other coexisting problems. As such we consider our findings complementary to clinical reports of intravenous Lidocaine therapy.1-5 We should also comment on the absence of an analgesic effect when using either heat pain or cold pain. For the purpose of the heat pain evaluation, we used suprathreshold temperatures that were adjusted to an individual’s threshold and tolerance. This approach was chosen to reduce the known variability in pain perception. This finding is not entirely surprising, as even well established analgesics such as morphine do not change heat pain tolerance in several studies. 27,28 Furthermore, we should keep in mind that for decades lidocaine has only been used as local anesthetic and, given systemically, as antiarrhythmic drug. It has not been until more recently that the drug has been used as intravenous analgesic to a variety of neuropathic pain states.

In summary, our study demonstrates that systemic lidocaine at a dose well below the toxic level produces a small but significant analgesic effect in this single-blinded prospective healthy human volunteer study. This finding testifies to an analgesic effect using intravenous lidocaine that extends beyond its use in chronic pain. If evaluated carefully, systemic lidocaine may have a role as supplementary therapeutic modality in acute pain states such as post-surgical pain or acute pain superimposed on underlying chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable organizational contribution of Ms. Debbie Owen.

Identification of financial source(s) which support the work

This publication (or project) was supported by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (Carl Koller Memorial Research Grant), the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science grant number UL1 RR025777 and the NIH, grant number K23RR021874

Identification of any meetings where the work may have been presented

This work has not been presented publicly.

Identification of institution(s) where work is attributed

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Anesthesiology

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest (list below)

None of the authors have reported a conflict of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michael A. Froelich, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Jason L. McKeown, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Mark J. Worrell, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Timothy J. Ness, University of Alabama at Birmingham

References

- 1.Schafranski MD, Malucelli T, Machado F, et al. Intravenous lidocaine for fibromyalgia syndrome: an open trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:853–855. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vadalouca A, Siafaka I, Argyra E, Vrachnou E, Moka E. Therapeutic management of chronic neuropathic pain: an examination of pharmacologic treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1088:164–186. doi: 10.1196/annals.1366.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herroeder S, Pecher S, Schonherr ME, et al. Systemic lidocaine shortens length of hospital stay after colorectal surgery: a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:192–200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31805dac11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groudine SB, Fisher HA, Kaufman RP, Jr., et al. Intravenous lidocaine speeds the return of bowel function, decreases postoperative pain, and shortens hospital stay in patients undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:235–239. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaba A, Laurent SR, Detroz BJ, et al. Intravenous lidocaine infusion facilitates acute rehabilitation after laparoscopic colectomy. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:11–18. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00007. discussion 15-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Shafer SL, Yaksh TL. Prolonged alleviation of tactile allodynia by intravenous lidocaine in neuropathic rats. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:775–785. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199510000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ness TJ. Intravenous lidocaine inhibits visceral nociceptive reflexes and spinal neurons in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1685–1691. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200006000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ness TJ, Lewis-Sides A, Castroman P. Characterization of pressor and visceromotor reflex responses to bladder distention in rats: sources of variability and effect of analgesics. J Urol. 2001;165:968–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ness TJ, Randich A. Which spinal cutaneous nociceptive neurons are inhibited by intravenous lidocaine in the rat? Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SIEBECKER KL, KIMMEY JR, BAMFORTH BJ, STEINHAUS JE. Effect of lidocaine administered intravenously during ether anesthesia. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1960;4:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1960.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.STEINHAUS JE, HOWLAND DE. Intravenously administered lidocaine as a supplement to nltrous oxide-thiobarbiturate anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1958;37:40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace MS, Laitin S, Licht D, Yaksh TL. Concentration-effect relations for intravenous lidocaine infusions in human volunteers: effects on acute sensory thresholds and capsaicin-evoked hyperpathia. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:1262–1272. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith GM, Egbert LD, Markowitz RA, Mosteller F, Beecher HK. An experimental pain method sensitive to morphine in man: the submaximum effort tourniquet technique. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966;154:324–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fillingim RB, Ness TJ, Glover TL, et al. Morphine responses and experimental pain: sex differences in side effects and cardiovascular responses but not analgesia. The journal of pain: official journal of the American Pain Society. 2005;6:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephen Shafer MD. Stanpump (ed Version 1998): Open TCI. 1998. TCI program. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koppert W, Weigand M, Neumann F, et al. Perioperative intravenous lidocaine has preventive effects on postoperative pain and morphine consumption after major abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1050–1055. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000104582.71710.EE. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindblom . Quantitative testing of sensibility including pain. In: Stålberg E YR, editor. Clinical Neurophysiology. Butterworths; London: 1981. pp. 168–190. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frolich MA, Price DD, Robinson ME, Shuster JJ, Theriaque DW, Heft MW. The effect of propofol on thermal pain perception. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:481–486. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000142125.61206.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pace MC, Mazzariello L, Passavanti MB, Sansone P, Barbarisi M, Aurilio C. Neurobiology of pain. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:8–12. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chabal C, Russell LC, Burchiel KJ. The effect of intravenous lidocaine, tocainide, and mexiletine on spontaneously active fibers originating in rat sciatic neuromas. Pain. 1989;38:333–338. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bittar RG, Teddy PJ. Peripheral neuromodulation for pain. J Clin Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh DM, Howe TE, Johnson MI, Sluka KA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for acute pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006142.pub2. CD006142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao F, Williams M, Welsh DC, et al. fMRI investigation of the effect of local and systemic lidocaine on noxious electrical stimulation-induced activation in spinal cord. Pain. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCleane G. Intravenous lidocaine: an outdated or underutilized treatment for pain? Journal of palliative medicine. 2007;10:798–805. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace MS, Dyck JB, Rossi SS, Yaksh TL. Computer-controlled lidocaine infusion for the evaluation of neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Pain. 1996;66:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)02980-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Burght M, Rasmussen SE, Arendt-Nielsen L, Bjerring P. Morphine does not affect laser induced warmth and pin prick pain thresholds. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:161–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1994.tb03859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catheline G, Le Guen S, Besson JM. Intravenous morphine does not modify dorsal horn touch-evoked allodynia in the mononeuropathic rat: a Fos study. Pain. 2001;92:389–398. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senami M, Aoki M, Kitahata LM, Collins JG, Kumeta Y, Murata K. Lack of opiate effects on cat C polymodal nociceptive fibers. Pain. 1986;27:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]