Abstract

This study examined early elementary school children’s trajectories of peer victimization with a sample of 218 boys and girls. Peer victimization was assessed (via peer report) in kindergarten, 1st, 2nd, and 5th grades. Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was used to examine multiple types of relationships (mother-child, student-teacher, friendship) as predictors of kindergarten levels of peer victimization and changes in peer victimization across time. Results indicated that the mother-child relationship predicted kindergarten levels of peer victimization, and that the student-teacher relationship did not provide additional information, once the mother-child relationship was accounted for in the analyses. Friendship predicted changes in peer victimization during the elementary school years. Results are discussed in a developmental psychopathology framework with special emphasis on the implication for understanding the etiology of peer victimization.

Peer victimization is typically defined as repeated exposure to negative actions on the part of one or more people, often involving a real or perceived imbalance in strength or power (Camodeca, Goossens, Terwogt, & Schuengel, 2002; Olweus, 1991). Peer victimization is ubiquitous in schools, with over 75% of children and adolescents reporting harassment by peers within the last year (Hoover, Oliver, & Hazler, 1992); approximately 10% of children are identified as chronically, frequently, or severely victimized by their peers (Nansel et al., 2001). As such, peer victimization is a public policy issue and a major concern to school officials (Olweus, 2001).

Peer victimization is associated with many maladaptive outcomes, including depression, loneliness, and anxiety (Hodges & Perry, 1999; Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, and Bukowksi, 1999), as well as with externalizing behaviors, school avoidance, and academic failure (Hanish & Guerra, 2002; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). Although many of these associations are assessed via cross-sectional designs, preliminary evidence indicates that peer victimization predicts changes in symptomology and that these effects can linger after victimization has ceased (Kochenderfer-Ladd & Wardrop, 2001), even into adulthood (Olweus, 1992). Furthermore, children who are chronic, rather than transient, victims are more likely to exhibit internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001). Identifying factors that are associated with individual trajectories of peer victimization will help guide intervention efforts that seek to decrease the degree to which children are targets of peer victimization.

The developmental psychopathology framework is useful in conceptualizing the risk and protective factors associated with peer victimization. This framework acknowledges the multiple pathways children follow and highlights the fact that children who begin at the same point can diverge over time (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Research indicates that although many children are victimized at some point—particularly at younger ages—only a subset continues to become chronic victims (Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001). That is, most children will experience decreasing levels of peer victimization as they progress in elementary school, but some children will continue to receive high levels of peer victimization. One explanation for this decline is that aggressors begin to systematically target specific children, based on whether rewards are gained from victimizing a specific child. Most children will emerge as unappealing targets of aggression, but some children will continue to be targeted, because victimization leads to resources or confirmation of dominant status by the aggressors (Smith, Shu, & Madsen, 2001). However, there is much to be learned about which children will continue to be targets compared to those who will not. Thus, the notion of multifinality (Cicchetti, 2006) is directly applicable to the question of the development of peer victimization. Children’s relationships with individuals in their lives may at least partially explain why some children will become persistent and chronic targets of peer victimization.

Children are socialized by many agents in their environments, including parents, teachers, and peers. Relationships offer opportunities for children to develop a wide range of skills, including the self-regulatory, coping, and general social skills that have been shown to reduce children’s risk for peer victimization (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997; Olweus, 1978; Perry, Williard, & Perry, 1990). Positive relationships with important individuals in children’s lives may help protect children from becoming chronic targets of peer victimization. Although previous research has suggested that aspects of these relationships are related to peer victimization (e.g., Beran & Violato, 2004; Perren & Alsaker, 2006), developmental psychopathology theory emphasizes the importance of recognizing the complex realities of children’s social worlds, and encourages the simultaneous examination of multiple influences upon a child. A main goal of the current study was to determine whether the influence of multiple types of relationships (mother-child, student-teacher, dyadic friendship) provides unique or redundant information in the prediction of peer victimization trajectories.

The developmental psychopathology framework also emphasizes transition periods in children’s lives. The kindergarten year represents an important transitional period, and is a qualitatively different environment from preschool and home environments (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). In addition to increased academic demands, the social demands are also increased as children enter classrooms with larger child-to-adult ratios and confront growing expectations of independence and self-sufficiency. Problems that arise during this transition may persist across the school years and have important implications for children’s future school adjustment (Entwisle & Hayduck, 1988). Moreover, Perry and Weinstein (1998) highlight the importance of examining the social contexts that accompany the transition to kindergarten, as children’s relationships at this time may have immediate, as well as long-term, consequences for children’s social adjustment. From year to year, the quality of early student-teacher relationships (conflict; r = .36; Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004) and mother-child relationships is quite stable (responsiveness; r = .56; Feng, Shaw, Skuban, & Lane, 2007) as is friend status (i.e., whether or not a child has a friend). For example, in one study, over 70% of children had stable friend status over a one-year period (Wojslawowicz Bowker, Rubin, Burgess, Booth-LaForce, & Rose-Krasnor, 2006): that is, children who had a friend one year were likely to have at least one friend the following year. As the quality of children’s relationships in kindergarten is likely to be indicative of long-term trajectories of social adjustment, we were particularly interested in examining the association between relationships in kindergarten and changes in peer victimization across the elementary school years.

No study, to our knowledge, has tested the association of multiple relationships with peer victimization in a single model. Previous research, however, indicates that tested separately, the mother-child relationship (e.g., Beran & Violato) and friendships (e.g., Perren & Alsaker, 2006) are each associated with peer victimization. The student-teacher relationship is related to child social outcomes, more generally (e.g., Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994). Although these three types of relationships are related to peer victimization, it was of interest to determine whether the contributions they make to peer victimization are unique.

Maternal warmth is associated with lower levels of peer victimization (Beran & Violato, 2004); whereas, maternal overcontrol (e.g., overprotection, intrusiveness) is associated with higher levels of peer victimization (Paul, 2006; Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001; Stevens, De Bourdeaudhuij, & Van Oost, 2002). Perry and colleagues (2001) have proposed that maternal overcontrol is associated with peer victimization because it fosters a “victim schema,” whereby children come to view parents as threatening and controlling and come to see themselves as incapable and powerless. This cognitive style seems to contribute to peer victimization over time.

Thus, there is theoretical and empirical support suggesting the mother-child relationship is related to peer victimization. Given that the mother-child relationship precedes school entry, the quality of that early relationship may be particularly important in predicting children’s peer victimization upon school entry. Thus, it was expected that the mother-child relationship would be related to initial (kindergarten) levels of peer victimization. More specifically, maternal positivity (e.g., warmth) was expected to be associated with lower kindergarten levels of peer victimization and maternal overcontrol (operationalized as directiveness in the current study) would be related to higher kindergarten levels of peer victimization. Moreover, maternal effects tend to be long-lasting (Wakschlag & Hans, 1999). Thus, the effect was expected to be present in kindergarten and was not expected to change over time. That is, neither positivity nor directiveness was expected to have an effect on the changes in peer victimization. Finally, we did not expect to see an interaction between maternal positivity and directiveness. Although researchers have examined interactions between these two constructs to determine whether positive parent behaviors might compensate for less positive parent behaviors, interactions have rarely been identified (e.g., Caron, Weiss, Harris, & Catron, 2006; McKee, Colletti, Rakow, Jones, & Forehand, 2008).

Although no study has tested the association between the student-teacher relationship and peer victimization, the formation of a close, low-conflict relationship with the teacher is associated with numerous positive outcomes for children, including enhanced academic adjustment (Hamre & Pianta, 2005) and behavioral adjustment (Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994). The student-teacher relationship seems particularly powerful for children who are at-risk for academic or behavioral maladjustment (Decker, Dona, & Christenson, 2007). However, children who have high conflict relationships with their teachers may be at increased risk for negative outcomes (Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Myers & Pianta, 2008),

Teachers use warm and positive relationships with their students to encourage self-regulatory behaviors (Tyson, 2000); consequently, if children with better student-teacher relationships are more regulated, they may be less likely to be victimized by their peers. Furthermore, a teacher who has a warm, close relationship with a child may be more attuned to the particular needs—both academic and social—of that child. This awareness may lead to more intervention and assistance on the teacher’s part, thus decreasing the likelihood the child will be victimized. Although teachers state that they almost always intervene in cases of peer victimization, observations show that they typically intervene in fewer than 5% of the episodes (Craig & Pepler, 1997). A lack of awareness that these situations are occurring may be one major reason for the discrepancy. Thus, a close relationship may increase the likelihood that the teacher will become aware of victimization and stop it.

In contrast, having a high-conflict relationship with a teacher may inhibit the development of self-regulatory skills that are important for the prevention of peer victimization. Furthermore, teachers who have high conflict relationships with certain children may be less likely to intervene on their behalf, perhaps because they do not take the extra time to notice potential victimization situations. Moreover, not all teachers sympathize with victims of peer aggression (Boulton, 1997). Having a high conflict relationship with a child may decrease sympathy and concern. This relative lack of concern may be apparent to children in the classroom, who may come to believe that they can “get away with” victimizing that child, thus leading to higher levels of kindergarten victimization. We anticipated that, whereas closeness between students and teachers would be associated with lower initial (i.e., kindergarten) levels of peer victimization, conflict would be predictive of higher initial peer victimization scores.

The teacher relationship may also have important implications for changes (i.e., the slope of trajectories) in peer victimization. Whereas the mother-child relationship precedes school entry and its effects may not change over the early school years, the kindergarten student-teacher relationship is a new relationship for the child and skills gained in the context of this relationship may take time to emerge. Furthermore, social support and coping skills seem to be particularly important in the face of peer victimization (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1997). A lack of felt support from teachers may interfere with children’s ability to cope, thus encouraging more victimization over time. Therefore it was predicted that high conflict/low closeness student-teacher relationships would be associated with increasing levels of peer victimization over time.

Finally, friendship may protect children from peer victimization. Peer victimized children are less likely to have friends compared to non-victimized children (Perren & Alsaker, 2006). Nevertheless, there are peer-victimized children who do establish positive dyadic friendships despite their problems with the larger peer group (Goldbaum, Craig, Pepler, & Connolly, 2003). Among peer-victimized children, those without friends are more likely to see increases in peer victimization over time compared to those with friends (Boulton, Trueman, Chau, Whitehand, & Amatya, 1999). Moreover, once children have gained reputations as people who are teased and victimized, other children may be less likely to associate with them, thus decreasing the likelihood that they will develop new friendships. A cycle of friendlessness and victimization may be created. Therefore, kindergarten friend status (i.e., whether a child has a mutual friend in kindergarten) may be particularly important in predicting changes in peer victimization over time.

Despite the accumulating evidence that each of these relationships is associated with victimization from peers, these links have been studied in isolation. In a child’s life, these multiple relationships coexist and may influence one another as well as jointly influencing outcomes. The current study will provide evidence as to whether these relationships are uniquely related to peer victimization or whether they provide redundant information. Furthermore, we test whether interaction effects exist between the different types of relationships.

There are a number of reasons why mother-child, teacher-child, and friendship relationships would be uniquely related to children’s risk for peer victimization. Mother-child relationships are enduring and powerful forces in children’s lives, and many of the skills children develop in the context of the maternal relationship precede the environments in which children may be exposed to peer victimization. Teachers, on the other hand, may focus on helping children to develop skills that are particularly important in the school context, and the student-teacher relationship may facilitate such skill development. By encouraging children’s development of regulatory skills, as well as intervening when children are harassed by peers, teachers may contribute to children’s decreasing levels of peer victimization. Thus, both the mother-child relationship and the student-teacher relationship were expected to be uniquely associated with peer victimization.

Given that friendship relationships are most proximal to the outcome of interest, it was expected that friendship would be a strong predictor of trajectories of peer victimization, even after controlling for the quality of the student-teacher and mother-child relationships. Children’s peers are the individuals who are most likely to be present during victimization episodes and the most likely to intervene (Craig & Pepler, 1997). Teachers and parents are less likely to be aware of peer victimization problems, and thus may not be in as strong of a position to help children cope with and respond appropriately to peer victimization. Moreover, children may be less likely to harass or tease others with supportive ties within the larger peer group.

The developmental psychopathology framework emphasizes the notion of the interplay between risk and protective factors. Thus, we expected that there might be interactions between the relationship variables. Specifically, because we hypothesized effects of the mother-child relationship and the student-teacher relationship on kindergarten levels of peer victimization, we also considered whether the characteristics of the mother-child and student-teacher relationships worked interactively in the prediction of initial levels of peer victimization in kindergarten. The student-teacher relationship has been shown to be particularly important for children at risk for maladjustment (e.g., Decker, Dona, & Christenson, 2007) and can be conceptualized as a protective factor. Following this line of thought, we hypothesized that the quality of the student-teacher relationship would not be related to peer victimization in the context of low levels of maternal directiveness and high levels of maternal positivity. On the other hand, we expected that in the context of more negative aspects of the mother-child relationship (high directiveness and low warmth), the student-teacher relationship would be associated with peer victimization, such that positive aspects would be associated with lower kindergarten levels of peer victimization and negative aspects would be related to higher kindergarten levels.

In terms of predicting changes in peer victimization (i.e., predicting the slope), we reasoned that an interaction between friend status and the student-teacher relationship was possible. Children with friends may be less dependent on a positive student-teacher relationship. For children without friends, who may have fewer people who are willing to intervene in peer victimization situations and who may have fewer opportunities to develop important coping and conflict negotiation skills, the student-teacher relationship may be important. For these children, having a close, low-conflict relationship with a teacher may help them build the skills necessary to lead to decreases in peer victimization. The peer victimization problems for children with conflict relationships with teachers may be exacerbated. Finally, in line with previous research (Smith, Shu, & Madsen, 2001), we expected an overall decline in peer victimization over elementary school. However, we expected that children with positive aspects of the relationships would show a steeper decline, whereas children with negative aspects would show a shallow decline or demonstrate high stable trajectories.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study included 218 children who were part of a larger sample of 447 children participating in an ongoing longitudinal study. Children were assessed in Kindergarten, 1st grade, 2nd, and 5th grade. This sample is part of a longitudinal project in which children with externalizing problems were over-sampled, based on elevated scores on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 2–3; Achenbach, 1992) administered at age 2. The participants were originally recruited through child day care centers, the county health department, and the local Women, Infants, and Children program in order to obtain a broad, community-based sample of children (see Calkins, Dedmon, Gill, Lomax, & Johnson, 2002 and Calkins, Graziano, Berdan, Keane, & Degnan, 2008 for further information on recruitment procedures and original demographic information.) The current study’s sample of children (N = 218; 56% female) was racially and economically diverse (64% Caucasian; mean Hollingshead = 40.2, range: 13.5–66).

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992) was used for the analyses. HLM handles missing data at level-1 (in this case, peer victimization), but not at level-2 (relationship indices). The sample for this study was based on children providing data for all level-2 predictors and data on peer victimization for at least one time point (N = 218). All 218 participants had victimization data in kindergarten. Of these, 105 (48%) provided data at all four time points, 79 (36%) at three time points, 27 (12%) at two time points, and 7 (3%) at one time point. Of the missing data, 55% was due to being unable to contact the family, 21% was due to the family moving out of town, 11% was due to the principal declining, 8% to the parent declining, 2% to the teacher declining, 2% to the child being home schooled, and 1% due to collecting an insufficient number of consents from children’s classmates. There were no significant differences between children who provided complete data for the current study and those who provided partial data with regards to gender, minority status, or 2-year SES (Hollingshead scores). There was also no difference in at-risk status for externalizing problems.

Procedure

Consent was obtained from children’s parents for each aspect of the study prior to data collection. Consent for sociometric interviews was obtained from the local superintendent, the principal, the teacher, and the parents of children’s classmates. Only children whose parents provided consent were included in the sociometric assessment. To increase return rates, a small incentive such as a pencil was given to all children who returned a consent form, regardless of whether consent was granted. Furthermore, all children gave assent prior to the sociometric interview. Children’s peer and teacher relationships were measured through sociometric interviews and teacher self-report. Trained graduate students conducted sociometric interviews at every grade (K, 1, 2, & 5). The average participation rate was 63% (range: 24% - 100%). Peer victimization and friendship data were collected at these points; although for this study, friendship was considered at kindergarten only. Teachers completed several questionnaires on the target child at these assessments. The student-teacher relationship was also considered at kindergarten only. Again, we chose to examine these relationships in kindergarten, because we were interested in how relationship features at the transition to kindergarten predicted changes in peer victimization across early elementary school. Finally, children came to the lab with their mothers at age 5.5 and participated in several interactions together, which were videotaped and coded.

Measures

Peer victimization was assessed using a standard sociometric peer nomination procedure (see Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). In kindergarten through 2nd grade, children were individually interviewed at which time they were presented with a class roster and asked to indicate their answers by pointing to a picture of those classmates who fit a behavioral descriptor. In 5th grade, children began to rotate classes and became familiar with children across the grade, rather than just those children in their homerooms or primary classrooms. For the 5th-grade data collection, we chose to allow students to select from a list of all participating students in their grade, rather than limiting them to classmates. Thus, in 5th grade, interviews were administered in a group format, and children indicated their responses by selecting names from a roster of participating grademates. For peer victimization, children were told, “Some kids get picked on and made fun of by other kids. They get teased or get called names. Who gets picked on and teased by other kids?” Children were permitted to select as many or as few classmates (K-2nd) or grademates (5th) as they wanted (by pointing to pictures of classmates or selecting from a roster), but were encouraged to select at least three classmates. Because peer nomination data include information from multiple reporters, the reliability of single-item peer nomination scales tends to be quite high (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990).

Typically, this type of data is standardized within classroom; however, this procedure sets the mean to zero at every time point, making it difficult to detect change over time. Thus, we chose to use proportions of classmates who selected a child as “picked on or teased” as the score. This corrected for variations in class size, but allowed for the modeling of change over time. Most children were nominated by at least one classmate as “picked on or teased” (78.5% of kindergartners, 79.2% of 1st graders, 69.2% of 2nd graders, and 80.3% of 5th graders). Only nine children were never nominated as “picked on or teased.”

The number of children participating in each class at each grade level increased slightly from year to year (K: M = 12.55, SD = 3.6; 1st: M = 13.43, SD = 3.87; 2nd: M = 13.87, SD = 4.10). In 5th grade, an average of 49.24 grademates participated (SD = 22.39). Thus, overall observed decreases in peer victimization may overestimate the actual decrease and observed increases may underestimate the actual increase in peer victimization (i.e., if a child is nominated by 2 classmates as “picked on” at every year, his or her proportion score would decrease over time if his class size is increasing). Although none of the predictor variables were related to class size, class size was modestly and negative related to peer victimization scores (r = −.25, p < .01). Thus, the overall mean change should be interpreted with caution. However, observed deviations from the average trajectory based on the predictor variables should not be sensitive to class size and can be interpreted with more confidence.

Friend status was assessed as a part of the sociometric interview. In kindergarten, children were directed to select three classmates they liked to “play with a lot.” Children with at least one mutual nomination were coded as having a friend (friended). Children with three unreciprocated nominations were coded as having no identified friends (friendless). No child selected fewer than three classmates they liked to “play with a lot”. We chose to ask for limited, rather than unlimited friendship nominations, because we were interested in children’s close relationships. 72.5% of children had at least one mutual friendship in kindergarten.

The student-teacher relationship was assessed in kindergarten via teacher report. Teachers completed the Student-Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta, 2001), a 28-item scale that assesses a teacher’s perception of his or her relationship with a particular student. Teachers answer using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from Definitely does not apply to Definitely applies. This scale yields three subscales (Conflict, Closeness, and Dependency), which were created by adding the individual items within the subscale. The subscales can be combined into a total positive scale (with conflict and dependency reverse-coded). However, we chose to use the conflict and closeness scales as markers of positive and negative features of the student-teacher relationship, given that we also used positive and negative features of the mother-child relationship. The Conflict scale included 12 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .86) such as, “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other.” The Closeness scale included 11 items (Cronbach’s alpha = .81) such as, “This child values his/her relationship with me.”

The mother-child relationship was assessed during a laboratory visit. Mother-child dyads completed a series of tasks intended to measure mother-child interactions. The tasks included a teaching task in which mothers were asked to help their children construct a duplo tower to look like a model (4 min.); a puzzle task in which children completed a difficult puzzle and mothers were asked to help their children as needed (4 min.); a freeplay task in which mother-child dyads were given a selection of age-appropriate toys and asked to play as they normally would at home (5 min.); a compliance task in which mothers were asked to have their children pick-up the toys from the freeplay task (3 min.); and a pretend play task (6 min.) in which mothers and children were given a train set and asked to play as they normally would at home. Maternal behavior received codes for warmth/positive affect (displaying positive affect and warmth to the child), sensitivity/responsiveness (promptly and appropriately responding to the child’s bids to her), and strict/directive methods (directing child’s behavior so that there are few child-initiated actions). These were coded on 4-point scales ranging from low to high. The global codes were adapted from the Early Parenting Coding System (Winslow, Shaw, Bruns, & Kiebler, 1995) and broadly represent maternal interaction styles. Warmth and responsiveness were highly correlated (r = .75) and were averaged into one measure of positive maternal behaviors. Thus, there were two measures used: maternal directiveness and maternal positivity (warmth/responsiveness). The alpha coefficient for warmth/responsiveness was 0.88; the alpha coefficient for directiveness was 0.77. Reliability. Two research assistants coded together 10% of the total sample on all tasks. Another 10% was coded separately to assess reliability; weighted kappas for all items were above 0.7.

Externalizing behavior was used as a control and was assessed with the externalizing subscale of the CBCL. Mothers completed the CBCL for 2- to 3-year-olds (Achenbach, 1992) when children were 2 years of age. These scales have been shown to be a good index of externalizing behavior across childhood, and were used to select children. The externalizing scale consisted of 26 items that included the aggression and destructive subscales. Mothers rated their children on a 3-point scale (not true, sometimes true, often true) on questions such as, “Hits others,” and “Temper tantrums or hot temper.”

Results

Preliminary Analyses & Analytical Plan

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of predictor and outcome variables. Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Examination of correlations among the three types of relationship variables ranged from small and non-significant to weak and significant (|.03| ≤ rs ≤ |.20|). These results suggest that our relationship indices may be measuring something specific to the relationship and not to the child (e.g., temperament, general social skills), although measurement error cannot be ruled out.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for predictor and outcome measures.

| Measures | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Victimization (proportion score) | |||

| Kindergarten | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.00 – 0.57 |

| 1st Grade | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.00 – 0.44 |

| 2nd Grade | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.00 – 0.71 |

| 5th Grade | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.00 – 0.62 |

| Teacher Relationship (Kindergarten) | |||

| Conflict | 21.62 | 7.75 | 12 – 52 |

| Closeness | 42.89 | 5.89 | 23 – 54 |

| Mother-Child Relationship (Kindergarten) | |||

| Directiveness | 2.07 | 0.61 | 1 – 4 |

| Positivity | 2.76 | 0.62 | 1 – 4 |

| % friended | % friendless | ||

| Friend Status (Kindergarten) | 72.5% | 27.5% | |

Table 2.

Inter-correlations of predictor and outcome measures.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Friend Status (K) | --- | ||||||||

| 2. Teacher Conflict (K) | −0.13* | --- | |||||||

| 3. Teacher Closeness (K) | 0.09 | −0.31*** | --- | ||||||

| 4. Maternal Directiveiness (K) | −0.11 | 0.20** | −.11+ | --- | |||||

| 5. Maternal Positivity (K) | 0.15* | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.18** | --- | ||||

| 6. Peer Victimization (K) | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.08 | --- | |||

| 7. Peer Victimization (1st Grade) | −0.07 | 0.20** | −0.02 | 0.08 | −.13+ | 0.02 | --- | ||

| 8. Peer Victimization (2nd Grade) | −0.16* | 0.13+ | −0.08 | 0.20** | −0.10 | 0.11 | 0.21** | --- | |

| 9. Peer Victimization (5th Grade) | −0.26** | 0.13+ | 0.07 | 0.17* | 0.03 | −0.003 | 0.23** | 0.30*** | --- |

Note. K = Kindergarten,

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

All analyses were conducted using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992), with full maximum likelihood estimation. HLM was used because it allows for unbalanced designs so those children with incomplete outcome data (level 1) could be included in the analyses. Peer victimization was measured in kindergarten, 1st, 2nd, and 5th grades. All other variables were assessed in kindergarten. Grade was centered at kindergarten (K = 0; 1st = 1; 2nd = 2; 5th = 5) so that the intercept indicated initial (kindergarten) levels of peer victimization. Friend status was entered as a dichotomous variable (friended = 1; friendless = 0), and continuous predictor variables were centered at their means. Individual growth modeling requires first testing an unconditional growth model (level 1), which contains no level 2 predictors variable. The purpose of this analysis is a) to determine the overall trajectory of children’s peer victimization in the sample and b) to determine whether there is enough individual variation around the overall peer victimization trajectory to warrant testing conditional models.

Analyses at level-2 (predictors of trajectories) can be performed once satisfactory individual variation around the mean trajectory has been established. In the current study, we examined variability in interindividual change in peer victimization by adding kindergarten relationship indices to predict initial levels of peer victimization and to predict increases or decreases in peer victimization from kindergarten to 5th grade. We first tested each relationship index in isolation, so that the results could be compared to previous research. We then tested a full model. We did not test all possible main effects or interactions; rather, we entered variables based on the individual models. For example, if a variable was shown to be significant only on the intercept (kindergarten levels) and not the slope in the individual model, then this variable and any interactions including this variable were included only in the intercept. Different models were fit sequentially using a backward elimination method where the full model was fit and then non-significant predictors were removed one by one. We then examined the p-values of the three-way interactions (if the individual models suggested that all three variables should be included in the intercept or the slope), and these were removed one at a time, starting with the highest (most non-significant) p-value (as long as p > .05). The same process was used for the two-way interactions, then for the main effects. Given that we were comparing nested models, we used the chi-square significance test between deviance scores to determine best fit.

Growth Models

Coefficients, random effects, and model fit statistics are presented in Table 3. Data are presented only for selected models, not for every model that was tested using the backward elimination procedure.

Table 3.

Results of selected hierarchical linear models for change in peer victimization across elementary school (N = 218)

| Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

||

| Fixed effects | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | |

| Intercept (Kindergarten) | 0.134*** (0.0063) | 0.142*** (0.0122) | 0.134*** (0.0063) | 0.133*** (0.0063) | 0.035 (0.0860) | 0.140*** (0.0121) | |

| K Friend Status (friended) | 0.012 (0.0142) | 0.136 (0.1183) | −0.010 (0.0142) | ||||

| K Teacher Conflict | 0.002* (0.0006) | 0.005 (0.0038) | |||||

| K Maternal Directiveness | 0.021** (0.0079) | 0.060 (0.0417) | 0.020* (0.0078) | ||||

| Conflict by Directiveness | −0.002 (0.0015) | ||||||

| Conflict by Friend Status | −0.006 (0.0049) | ||||||

| Friend Status by Directiveness | −0.062 (0.0507) | ||||||

| Friend Status by Directiveness by Conflict | 0.002 (0.002) | ||||||

| Slope (Grade) | −0.013*** (0.0022) | −0.006 (0.0042) | −0.013*** (0.0022) | −0.013*** (0.0021) | −0.006 (0.0042) | −0.006 (0.0042) | |

| K Friend Status (friended) | −0.009+ (0.0049) | −0.010* (0.0049) | −0.009+ (0.0049) | ||||

| Variance Components | Variance | Variance | Variance | Variance | Variance | Variance | |

| Level 1 | Within person | 0.0094 | 0.0094 | 0.0094 | 0.0094 | 0.0093 | 0.0094 |

| Level 2 | Initial Status | 0.0030*** | 0.0031*** | 0.0029*** | 0.0028*** | 0.0028*** | 0.0028*** |

| Rate of Change | 0.00014* | 0.00014* | 0.00014* | 0.00014* | 0.00014* | 0.00013* | |

| Goodness-of-Fit | |||||||

| Deviance | −1151.91 | −1162.66 | −1158.31 | −1159.01 | −1173.47 | −1168.89 | |

Note: Model A = Unconditional Growth; Model B = Final Model with Friend Status; Model C = Final Model with Student-Teacher Conflict; Model D = Final Model with Maternal Directiveness; Model E = Full Model with three relationship variables (as suggested by previous models), Model F (best fitting final model);

p<.06

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

The unconditional linear growth model (Model A; Table 3) of peer victimization was significant both at the intercept (kindergarten; coefficient = .134, p < .001) and slope (coefficient = −.013, p < .001). These parameters indicate that in kindergarten, the average child is nominated as “teased” by approximately 13% of his or her classmates. This level decreases by .013 (1 percentage point) per year, such that by 5th grade, the average child is nominated as “teased” by approximately 8% of his or her classmates. Moreover, variance components (random effects) were significant, which indicated sufficient individual variability around both the intercept and the slope to add level-2 predictors (see Table 3).

We first tested whether demographic variables (gender, race, SES) predicted peer victimization. None were significant and thus all were excluded from further analyses. Given that externalizing behavior was initially over-represented in our sample, we also tested whether 2-year externalizing scores from the CBCL should be included as a control variable. We found that the CBCL score did not predict the slope of peer victimization scores, but did predict the intercept (coefficient = .001, p < .05). The CBCL is measured using a T-score, having a standard deviation of 10. Thus, for a 10-point (1 SD) increase above the mean, there would be an increase of .01 in peer victimization score; that is, a child whose CBCL score was 1 SD above the mean would be predicted to have been nominated as victimized by approximately 14% of his or her classmates.

Two-year CBCL scores were thus included as a control variable following suggestions by Singer and Willett (2003). The goal was to determine whether models still exhibited good fit after controlling for early externalizing. After the reduced model was determined for each relationship variable in isolation and in the final reduced model, externalizing was added to ensure that the variables of interest were still significantly related to the outcome.

Although our goal was to test relationship indices simultaneously, we first tested them in isolation so the results could be more directly compared to previous studies. Kindergarten friend status was entered as a level-2 predictor (friended = 1; friendless = 0). It was not a significant predictor of kindergarten levels of peer victimization, although it was a significant predictor of peer victimization trajectories. The non-significant predictor of the intercept was maintained in the model. More specifically, children with friends displayed a steeper decline in peer victimization over time compared to children who were friendless in kindergarten (coefficient = −.009, p < .05). The parameters (Model B; Table 3) indicate that the average child is nominated by approximately 13% (friended) to 14% (friendless) of his or classmates in kindergarten, but the difference between friend status groups was non-significant. Children who were friendless in kindergarten saw, on average, a decrease of .006 in their peer victimization scores per year, suggesting that by 5th grade, these children were nominated by approximately 11% of their peers as victimized. Children who had mutual friends in kindergarten, on the other hand, had an additional average decrease of 0.009 (0.015 total) per year, suggesting that by 5th grade, friended children were being nominated as victimized by approximately 6% of their classmates. These results remained significant once externalizing was entered as a control variable.

The student-teacher relationship was next tested as a level-2 predictor. Closeness was tested first, then conflict, then with both variables (additive and multiplicative). Closeness did not predict kindergarten levels of peer victimization (intercept) or changes in peer victimization over time (slope), nor did closeness interact with conflict to predict peer victimization. However, conflict in the student-teacher relationship was positively associated with kindergarten levels of peer victimization (coefficient = .001, p < .01), such that children with more conflict in their relationships with their teachers were more likely to be victimized by peers in kindergarten. Conflict was not a significant predictor of slope, suggesting that the effect of the kindergarten student-teacher conflict on peer victimization is constant across elementary school. These results (Model C; Table 3) indicated that for each standard deviation increase in student-teacher conflict (SD = 7.75), the kindergarten peer victimization score increased by .008. That is, a child with a student-teacher conflict score 1 SD above the mean would be predicted to have been nominated as victimized by approximately 14% of his or her kindergarten classmates. The more complex model did not evidence better fit, based on the χ2 deviance test (ΔDeviance = 2.23, df = 5, p > .05). Thus, the more parsimonious model was retained, and closeness was dropped from further analyses. When externalizing was added, student-teacher conflict remained significant.

The mother-child relationship was tested next, in the same manner as the student-teacher relationship. Maternal positivity was first tested as a predictor, then maternal directiveness, then with both (additive and multiplicative). Maternal positivity was not a significant predictor of kindergarten levels of peer victimization or of change across time. The interactions between positivity and directiveness were not significant. Maternal directiveness was a significant predictor of the intercept (coefficient = .021, p = .01), but not of the slope. Higher levels of maternal directiveness were associated with higher levels of peer victimization in kindergarten, and this difference remained stable (i.e., the slope did not change) during elementary school (Model D; Table 3). A child with a maternal directiveness score 1 SD (.61) above the mean would be predicted to have an increase of .013 in kindergarten peer victimization; that is, the child would be expected to be nominated as victimized by approximately 14% of his or her classmates. As with the student-teacher analysis, the more complex model did not evidence significantly better fit (ΔDeviance = 2.8, df = 5, p > .05). Maternal directiveness was retained in favor of the more parsimonious model. Maternal positivity was dropped from further analyses. The results remained significant when externalizing was included as a control.

We next tested the relationship indices in a single model. Maternal warmth and student-teacher closeness were not included, because the simple models suggested that maternal directiveness and student-teacher conflict were the aspects of the relationships that were related to peer victimization. Based on the backward elimination procedure and the deviance comparison, models with interactions terms among the predictor variables were not supported (Model E; Table 3). The final reduced model (Model F; Table 3) indicated that maternal directiveness was significantly associated with initial kindergarten levels (intercept) of peer victimization (coefficient = 0.020, p < .05). Kindergarten friend status also continued to be a predictor of peer victimization trajectories (coefficient = −.009, p = .053), although not of the initial kindergarten levels. Stated another way, kindergarten friend status interacted with time to predict peer victimization. For this model, the trajectory of peer victimization was predicted by the following equation:

The intercept for individual i is denoted by π0i, and π1i is the linear slope. β00 is the coefficient for the mean intercept; β01 represents the increase over the mean intercept for children with friends;β02 represents the increase over the mean intercept for one unit increase of maternal directiveness; β10 is the coefficient for the mean slope; and β11 represents the increase over the mean slope for children with friends.

The χ2 deviance test indicated that the final model fit significantly better than the unconditional growth model (ΔDeviance = 16.98, df = 3, p < .001). The proportion of total outcome variation explained by the final model was estimated by pseudo-R2y, ŷ (0.49) which suggested that 49% of the variance was explained by all predictors included in the model (Singer & Willett, 2003). The proportional reduction in residual variance was also computed for the slope and the intercept. The pseudo- R2intercept (0.071) indicated a 7% reduction in variance associated with the intercept from the unconditional growth model to the final reduced model. The pseudo- R2slope (0.043) indicated a 4% reduction in variance associated with the slope.

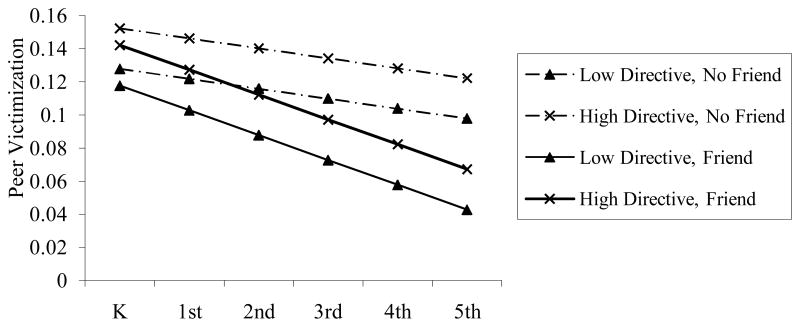

The parameters for the final model suggested that children with directive mothers were more likely to be victimized in kindergarten than were children with mothers who were less directive. Children whose mothers were 1 SD above the mean on directiveness would be expected to be nominated as victimized by approximately 15% of their kindergarten classmates, compared to approximately 13% for children whose mothers were 1 SD below the mean. As children age, initial friend status becomes more important. Regardless of the mother’s directiveness, children with friends in kindergarten had much lower levels of peer victimization by 5th grade than children without friends in kindergarten. Within friend status groups (friended, friendless), children with directive mothers were more victimized than children with non-directive mothers (Figure 1). That is, by 5th grade children who were friendless in kindergarten and whose mothers were 1 SD above the mean on directiveness would be predicted to be nominated by approximately 12% of their classmates, compared to approximately 10% for friendless children whose mothers were 1 SD below the mean. Friended children in kindergarten whose mothers were 1 SD above the mean would be expected to be nominated by approximately 8% of their 5th grade classmates; whereas, friended children whose mothers were 1 SD below the mean would be expected to be nominated by approximately 4% of their 5th grade classmates. These effects remained significant when controlling for externalizing.

Figure 1.

Final model of relationship indices predictors of peer victimization (proportion of classmates nominating child as “teased”) trajectories: Maternal directiveness (intercept) and friend status (intercept and slope).

Note: High Directive = 1 SD above the mean for maternal directiveness; Low Directive = 1 SD below the mean

Discussion

Given the potential of chronic peer victimization to lead to psychological distress and behavioral maladaptation (Hanish & Guerra, 2002; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996; Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001), it is important to identify the factors that might protect children from becoming chronic victims. Using the developmental psychopathology framework to guide our thinking, we tested the influence of three relationships on trajectories of peer victimization: mother-child, student-teacher, and friend relationships. When considered together, we found the mother-child and friend relationships made unique predictions, but accounted for different aspects of children’s peer victimization trajectories. To our knowledge, no study to date has tested multiple relationships in a single model.

On average, we found a decline in peer victimization during elementary school. Although this decline may have been due to a statistical artifact (class sizes were increasing across this period as well), there are theoretical reasons to expect a decline (e.g., Smith, Madsen, & Moody, 1999). First, aggression is also declining during this period (Kokko, Tremblay, Lacourse, Nagin, & Vitaro, 2006), which means there may be fewer chances for children to be harassed or victimized. Second, as children age, they are more able to distinguish various peer behaviors and their nominations may become more specific and stable (Graziano, Berdan, Keane, & Balentine, 2004). Third, children may be less specific in whom they victimize at younger ages. Children who are picked on and respond in ways that do not reward the aggressor (ignoring, assertive responding) may be less likely to be victimized in the future, whereas children who respond in ways that reward the aggressor (showing fear, acquiescing, reactive/ineffective aggression) may continue to be victimized (Smith, Shu, & Madsen, 2001). Thus, over time, fewer children are identified as peer victimized.

Another explanation is that victimization is not declining per se; rather, children’s classmates could be coming to a consensus about who is and is not victimized by their peers. It is difficult to tell whether this is the case from the current data. If this were the explanation, one might also expect a decrease in variability. In our data, variability in kindergarten was similar to the variability in 5th grade. Moreover, previous studies have similarly shown declining trajectories of peer victimization using peer reports among preadolescents (Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005) and among adolescents (Nylund, Bellmore, Nishina, & Graham, 2007). Future researchers can help to rule out this explanation by having peers rate each classmate on a continuum of peer victimization, rather than using nominations. A better approach may be to combine multiple reports (peer, teachers, self) to avoid bias from any one perspective.

What is clear from our data is that indices of important relationships predict different patterns of peer victimization across elementary school. Our data indicated that maternal directiveness predicted kindergarten levels of peer victimization only; that the association between the student-teacher conflict and kindergarten peer victimization was non-significant after accounting for maternal directiveness; and that friend status predicted the trajectory of peer victimization, but not initial kindergarten levels.

Taken separately, maternal directiveness and student-teacher conflict demonstrated overlapping associations with kindergarten peer victimization. Although directiveness and conflict are not synonymous, they represent potentially negative aspects of both relationships. Moreover, both of these relationships are vertical to the child and may influence outcomes in similar ways compared to lateral relationships (e.g., peers, friends, siblings). The maternal relationship, however, is an enduring and more powerful relationship compared to those of teachers. Moreover, children’s self-regulatory skills—which may be important in preventing peer victimization (Monks, Smith, & Swettenham, 2005; Toblin, Schwartz, Gorman, & Abou-ezzedine, 2005)—develop beginning in infancy, toddlerhood, and the preschool years, and the mother-child relationship is implicated in the successful development of these behaviors (Rubin, Coplan, Fox, & Calkins, 1995). Furthermore, these findings suggest that maternal involvement in the school transition may be particularly helpful for successfully navigating the new social demands children face in elementary school.

The finding that maternal directiveness predicted kindergarten levels of peer victimization is consistent with previous literature suggesting that maternal overcontrol is associated with peer victimization (Ladd & Ladd, 1998), perhaps through the development of a victim schema (Perry, Hodges, & Egan, 2001). The current study demonstrates that the effect of maternal overcontrol is evident upon school entry and persists throughout elementary school. This finding suggests including mothers in interventions for young children who are targets of peer victimization would be important. A focused strategy might be to have mothers and young children (kindergartners) discuss hypothetical instances of peer victimization. In the context of these discussions, both the mother’s tendency to control/direct and the child’s strategies to deal with the conflict could be improved.

The difference in magnitude between the trajectories of children with highly directive mothers and children with non-directive mothers was consistent from kindergarten to 5th grade. That is, there was no effect on the slope. This is not surprising, considering that the mother-child relationship, and maternal behaviors in particular, are quite stable (Feng, Shaw, Skuban, & Lane, 2007). Moreover, other relationships—at least the aspects we measured—do not seem to serve as protective factors for children with highly directive mothers. Future research should determine what other factors (e.g., father-child relationships, temperamental factors, emotion regulation) might decrease the association between maternal overcontrol and peer victimization. For example, emotional responses (e.g., crying, reactive aggression) have been associated with higher levels of peer victimization (Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997; Smith, Shu, & Madsen, 2001). Children with high emotional reactivity in combination with maternal overcontrol may be at the greatest risk for peer victimization; whereas, for children with average levels of emotional reactivity, maternal overcontrol may have a weaker association with peer victimization.

Interestingly, it was only the negative aspects of these vertical relationships (maternal directiveness / student-teacher conflict) that seemed to predict peer victimization. One possible explanation is that maternal overcontrol decreases the likelihood that children will be able to deal successfully with conflict in a variety of relationships, including with teachers, peers, and friends. Conflict resolution skills might mediate the association between maternal overcontrol and conflictual relationships in general.

Friend status also emerged as a significant predictor of children’s peer victimization, although this difference did not emerge until after kindergarten (due to different slopes). Unlike the other relationships, a measure of quality was not gathered, so it is unclear whether negative aspects of friendship interactions might be more strongly related to peer victimization than positive ones among children who have friends. Although children always have relationships with teachers and caregivers (making the presence or absence of such a relationship meaningless), children do not necessarily participate in reciprocated friendship dyads. Understanding the role of friendship quality will be important for future research, but the fact that friendless children are at significantly higher risk of peer victimization across elementary school may have important implications for intervention efforts.

Children without friends displayed a slight decrease in peer victimization across elementary school; however, this decrease was much steeper in children with friends. By 5th grade, the effect of friend status seems to eclipse the effect of maternal directiveness. That is, the difference in peer victimization between friended and non-friended children seems to be greater than the difference between children with high and low levels of maternal directiveness. However, it should be noted that maternal directiveness still predicted differences within friend status groups. The delay in the association between friend status and victimization is interesting. It is possible that aggressors initially target many children, but through a process of reward (e.g., responses of fear and frustration from victims) and punishment (e.g., retaliation by a friend) come to victimize certain children. However, if this were the primary factor, we would not expect any variable to predict kindergarten peer victimization—it would be random. Another explanation is that friendships provide the opportunity for children to practice the social skills that discourage peer victimization, but that the acquisition of these skills emerges slowly. Interventions may want to focus on increasing the likelihood that victimized children will develop friendships. For children who are victimized upon school entry, including a friendship skills building component in interventions may be important for their long-term social adjustment.

The current study provides important evidence about the types of relationships that are associated with peer victimization. There are several limitations, however, that should be acknowledged. First, the indices of relationships were not identical in terms of methods (mutual report of friendship, teacher-report of quality, observer coding). Although the mother-child and student-teacher relationships both had measures of potentially negative and positive aspects of the relationship, for friendship, we only measured the presence or absence of a friend. Future research should certainly use similar methods to measure relationship quality. Multiple perspectives should also be gathered, including child-report, other-report (teacher, peer, parent), and observations. It will be particularly important to include measures of friendship quality. Although these results suggest having a friend is better than not having a friend, low-quality friendships may be detrimental for a child. Friendships characterized by conflict, betrayal, and jealousy may foster the development of maladaptive conflict resolution skills, such as revenge (Dunn & Slomkowski, 1992). Thus, a low quality friendship may leave a child more vulnerable to peer victimization than a child without a mutual friend at all. Whether this is the case remains an open empirical question. Moreover, interactions between relationship types—not supported in the current study—may be detected when more similar aspects of relationships are considered.

A second issue is that we used single-time assessments of relationships. We were particularly interested in the relationships that exist as children make the transition to elementary school, as kindergarten adjustment to this transition can influence adjustment across elementary school and beyond. However, these relationships are ongoing and dynamic, and future investigations of how changes in these relationships over time influence trajectories of peer-victimization may help us further understand the causes and correlates of peer victimization. Furthermore, examining how changes in multiple relationships interact will also be important. For example, in longitudinal studies, it seems that friendship disturbances (e.g., moving from friended to friendless) precede rather than follow peer victimization (Pellegrini & Long, 2002). Perhaps conflict-free student-teacher relationships do not protect chronically friendless children, but might be protective of children who have lost a friend until they are able to establish another close friendship.

It should also be noted that the mother-child relationship preceded entry into kindergarten, but friend status and the student-teacher relationship did not. Had we included measures of pre-school student-teacher relationships and friendships, the results may have differed. For example, LoCasale-Crouch, Masburn, Downer, and Pianta (2008) found that kindergartners had better social and academic adjustment when their pre-kindergarten teachers used practices aimed at preparing young children for the transition to kindergarten. Thus, the association between child outcomes and the student-teacher relationship may be more important before the child is exposed to the new social and academic demands of kindergarten. The level of exposure to non-maternal caregivers (daycare workers or pre-school teachers) may also be related to adjustment. For example, more time spent in non-maternal care prior to kindergarten is associated with conflict with adults in kindergarten, although this effect is modest and smaller than the effect of the mother-child relationship (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2003). Thus, we might expect modest effects, but it would likely not overshadow the effects of maternal directiveness seen in the current study.

In summary, this study provides evidence that multiple relationships are associated with children’s trajectories of peer victimization. The results highlight the necessity of assessing multiple relationships within one study. Had we relied on analyses involving relationships in isolation, we would have concluded that the student-teacher relationship had an immediate and lasting effect on children’s peer victimization. When considered simultaneously with the mother-child relationship, the student-teacher relationship was no longer significant. It seems that researchers should focus on maternal factors in studying the emergence of peer victimization, while children’s kindergarten friendships seem more important in understanding the persistence of peer victimization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) awards (MH 55625 and MH 58144) to the third author and an NIMH award to the second and third authors (MH 55584). We thank the parents and children who have repeatedly given their time and effort to participate in this research. Additionally, we are grateful to the entire RIGHT-Track staff for their help in data collection, entry, checking, coding, etc. Amanda Williford provided us with statistical help. Thanks also to Lilly Shanahan for helpful comments on an earlier draft. Elizabeth Shuey, Jessica Moore, Ana Zdravkovic, Evin Lawson, Niloofar Fallah, Jason Boye, and Stephanie Doty provided excellent insights and support throughout the process, and we are grateful for their help.

Contributor Information

Rachael D. Reavis, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Susan P. Keane, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Susan D. Calkins, Department of Human Development and Family Studies & Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the child behavior checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of VT Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beran T, Violato C. A model of childhood perceived peer harassment: Analyses of the Canadian national longitudinal survey of children and youth data. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and applied. 2004;138(2):129–147. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.138.2.129-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M. Teachers’ views on bullying: Definitions, attitudes, and ability to cope. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;67(2):223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1997.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M, Trueman M, Chau C, Whitehand C, Amatya K. Concurrent and longitudinal links between friendship and peer victimization: Implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22(4):461–466. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk A, Raudenbush S. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins S, Dedmon S, Gill K, Lomax L, Johnson L. Frustration in infancy: Implications for emotion regulation, physiological processes, and temperament. Infancy. 2002;3(2):175–197. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins S, Graziano P, Berdan L, Keane S, Degnan K. Predicting cardiac vagal regulation in early childhood from maternal-child relationship quality during toddlerhood. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50(8):751–766. doi: 10.1002/dev.20344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca M, Goossens F, Terwogt M, Schuengel C. Bullying and victimization among school-age children: Stability and links to proactive and reactive aggression. Social Development. 2002;11(3):332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Caron A, Weiss B, Harris V, Catron T. Parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology: Specificity, task dependency, and interactive relations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccheti D. Development and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 6. New Jersey: Wiley; 2006. pp. 798–828. [Google Scholar]

- Coie J, Dodge K, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18(4):557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Coie J, Dodge K, Kupersmidt J. Peer group behavior and social status. In: Asher S, Coie J, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Craig W, Pepler D. Observations of bullying and victimization in the school yard. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 1997;13(2):41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Decker D, Dona D, Christenson S. Behaviorally at-risk African American students: The importance of student-teacher relationships for student outcomes. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45(1):83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Slomkowski C. Conflict and the development of social understanding. In: Shantz C, Hartup WW, editors. Conflict in child and adolescent development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 70–92. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle D, Hayduck L. Lasting effects of elementary school. Sociology of Education. 1988;61(3):147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw D, Skuban E, Lane T. Emotional exchange in mother-child dyads: Stability, mutual influence, and associations with maternal depression and child problem behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(4):714–725. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbaum S, Craig W, Pepler D, Connolly J. Developmental trajectories of victimization: Identifying risk and protective factors. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2003;19(2):139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano P, Berdan L, Keane S, Balentine C. Are young children good reporters of behavior? Validation of new sociometric constructs. Poster presented at the Conference on Human Development; Washington, DC. Apr, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre B, Pianta R. Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72(2):625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish L, Guerra N. A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(1):69–89. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges E, Perry D. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(4):677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges E, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski W. The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(1):94–101. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover J, Oliver R, Hazler R. Bullying: Perceptions of adolescent victims in the Midwestern USA. School Psychology International. 1992;13(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Matheson C, Hamilton C. Maternal, teacher, and child care history correlates of children’s relationships with peers. Child Development. 1994;65(1):264–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer B, Ladd G. Peer victimization: Manifestations and relations to school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology. 1996;34:267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer B, Ladd G. Victimized children’s responses to peer’s aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Developmental Psychopathology. 1997;9(1):59–73. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Wardrop J. Chronicity and instability of children’s peer victimization experiences as predictors of loneliness and social satisfaction trajectories. Child Development. 2001;72(1):134–151. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokko K, Tremblay R, Lacourse E, Nagin D, Vitaro F. Trajectories of prosocial behavior and physical aggression in middle childhood: Links to adolescent school dropout and physical violence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(3):403–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G, Burgess K. Do relational risks and protective factors moderate the linkages between childhood aggression and early psychological and school adjustment? Child Development. 2001;72(5):1579–1601. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G, Ladd B. Parenting behaviors and parent-child relationships: Correlates of peer victimization in kindergarten? Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(6):1450–1458. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoCasale-Crouch J, Mashburn A, Downer J, Pianta R. Pre-kindergarten teachers’ use of transition practices and children’s adjustment to kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2008;23(1):124–139. [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Colletti C, Rakow A, Jones D, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13(3):201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks C, Smith P, Swettenham J. Psychological correlates of peer victimisation in preschool: Social cognitive skills, executive function and attachment profiles. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31(6):571–588. [Google Scholar]

- Myers S, Pianta R. Developmental commentary: Individual and contextual influences on student-teacher relationships and children’s early problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(3):600–608. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel T, Overpeck M, Pilla R, Ruan W, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Early Child Care Research Network. Does amount of time spent in child care predict socioemotional adjustment during the transition to kindergarten? Child Development. 2003;74(4):976–1005. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Graham S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development. 2007;78(6):1706–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. Oxford; England: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Victimization among school children. In: Baenninger R, editor. Targets of violence and aggression. Oxford, England: North-Holland; 1991. pp. 45–102. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long-term outcomes. In: Rubin K, Asendorpf J, editors. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Peer harassment: A critical analysis and some important issues. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in schools: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Paul J. Peer victimization, parent-adolescent relationships, and life stressors. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Science and Engineering. 2006;66(10-B):5691. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini A, Long J. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20(2):259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, Alsaker F. Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry D, Hodges E, Egan S. Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and new model of family influence. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Perry D, Williard J, Perry L. Peers’ perceptions of consequences that victimized children provide aggressors. Child Development. 1990;61:1310–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry K, Weinstein R. The social context of early schooling and children’s school adjustment. Educational Psychologist. 1998;33(4):177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R. Implications of a developmental systems model for preventing and treating behavioral disturbances in children and adolescents. In: Hughes J, LaGreca A, Conoley J, editors. Handbook of psychological services for children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R, Stuhlman M. Teacher-child relationships and children’s success in the first years of school. School Psychology Review. 2004;33:444–458. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman S, Pianta R. An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten: A theoretical framework to guide empirical research. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2000;21(5):491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K, Coplan R, Fox N, Calkins S. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and preschoolers’ social adaptation. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7(1):49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge K, Pettit G, Bates J. The early socialization of aggressive victims of bullying. Child Development. 1997;68(4):665–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J, Willett J. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Madsen K, Moody J. What causes the age decline in reports of being bullied at school? Towards a developmental analysis of risks of being bullied. Educational Research. 1999;41(3):267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Shu S, Madsen K. Characteristics of victims of school bullying: Developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harrassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 332–352. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe L, Rutter M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55(1):17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens V, De Bourdeauhuij I, Van Oost P. Relationship of the family environment to children’s involvement in bully/victim problems at school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31(6):419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Toblin R, Schwartz D, Gorman A, Abou-ezzeddine T. Social-cognitive and behavioral attributes of aggressive victims of bullying. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26(3):329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Ladd G. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2005;76(5):1072–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson K. Using the teacher-student relationship to help children diagnosed as hyperactive: An application of intrapsychic humanism. Child and Youth Care Forum. 2000;29(4):265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag L, Hans S. Relation of maternal responsiveness during infancy to the development of behavior problems in high-risk youths. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(2):569–579. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow E, Shaw D, Bruns H, Kiebler K. Parenting as a mediator of child behavior problems and maternal stress, support, and adjustment. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Indianapolis, IN. 1995. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Wojslawowicz Bowker J, Rubin K, Burgess K, Booth-LaForce C, Rose-Krasnor L. Behavioral characteristics associated with stable and fluid best friendship patterns in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52(4):671–693. [Google Scholar]