Abstract

Background

Medical students' choice of residency specialty is based in part on their clerkship experience. Postclerkship interest in a particular specialty is associated with the students' choice to pursue a career in that field. But, many medical students have a poor perception of their obstetrics and gynecology clerkships.

Objective

To determine whether fourth-year medical students' perceptions of teaching quality and quantity and amount of experiential learning during the obstetrics-gynecology clerkship helped determine their interest in obstetrics-gynecology as a career choice.

Methods

We distributed an anonymous, self-administered survey to all third-year medical students rotating through their required obstetrics and gynecology clerkship from November 2006 to May 2007. We performed bivariate analysis and used χ2 analysis to explore factors associated with general interest in obstetrics and gynecology and interest in pursuing obstetrics and gynecology as a career.

Results

Eighty-one students (N = 91, 89% response rate) participated. Postclerkship career interest in obstetrics and gynecology was associated with perceptions that the residents behaved professionally (P < .0001) and that the students were treated as part of a team (P = .008). Having clear expectations on labor and delivery procedures (P = .014) was associated with postclerkship career interest. Specific hands-on experiences were not statistically associated with postclerkship career interest. However, performing more speculum examinations in the operating room trended toward having some influence (P = .068). Although more women than men were interested in obstetrics and gynecology as a career both before (P = .027) and after (P = .014) the clerkship, men were more likely to increase their level of career interest during the clerkship (P = .024).

Conclusions

Clerkship factors associated with greater postclerkship interest include higher satisfaction with resident professional behavior and students' sense of inclusion in the clinical team. Obstetrics and gynecology programs need to emphasize to residents their role as educators and professional role models for medical students.

Introduction

Many medical students have a poor perception of their obstetrics and gynecology clerkships.1 For the past several years, on the Association of American Medical Colleges graduation questionnaire, fourth-year medical students have consistently rated their experiences during their obstetrics and gynecology clerkship less favorably than their experiences in emergency medicine, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, and surgery.2 Students described specific areas for critique, including lack of faculty involvement in teaching, unclear learning objectives, inadequate feedback, limited opportunity for learning history-taking skills, and few experiences in learning physical examination skills.3,4

Additionally, recruitment of US medical students entering obstetrics and gynecology has declined. In the 1990s, 86% of obstetrics and gynecology residency positions were filled by US medical school graduates, but only 68% of obstetrics and gynecology residency positions were filled by US medical school graduates in 20035 and 65% in 2004.6 Although the trend has improved slightly in recent years, with 73% of positions being filled by US medical school graduates in 2007,7 medical student recruitment into obstetrics and gynecology remains a concern.

Studies examining medical student specialty selection note that clinical clerkships greatly influence students' career decision-making processes.8,9 Clerkships generate interest in the clerkship specialty, and postclerkship interest in a particular specialty is associated with students' choice to pursue a career in that field.8 Gariti and colleagues10 noted that 28% of students who initially considered obstetrics and gynecology, but later chose to enter another specialty, reported low satisfaction with their obstetrics and gynecology clerkship and indicated that the clerkship made the specialty less attractive. In contrast, those who chose to enter obstetrics and gynecology reported the clerkship made the specialty more attractive.

Hammoud and colleagues11 assessed the effect of the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship on students' interest in pursuing the field in a survey of students of 3 US medical schools. They found that students' sex and preclerkship interest in obstetrics and gynecology were the main factors associated with postclerkship interest in entering the field.11 Other factors outside of the clerkship experience contribute to a medical students' final decision to enter into obstetrics and gynecology. Studies show that perceptions of lifestyle, work hours, malpractice costs, and income influence specialty choice,12–18 and factors specific to obstetrics and gynecology, such as continutiy of patient care, surgical opportunities, and a healthy patient population, can make the field more attractive.12 Nonetheless, evidence does still suggest that the clerkship experience remains an important influential factor. In a multicenter survey of obstetrics and gynecology residents, more than 70% of those surveyed made their career decision after their third-year obstetrics and gynecology clerkship.19

In our study, we sought to explore which specific components of the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship influenced medical students' perceptions of and interest in obstetrics and gynecology. We hypothesized that 2 aspects of the clerkship have the greatest potential to influence student interest in obstetrics and gynecology: exposure to quality teaching and direct participation in examinations and procedures. We designed this study to address 2 main research questions: (1) Does the quantity and quality of teaching during the clerkship affect medical student interest in obstetrics and gynecology? and (2) Does the amount of hands-on learning experiences during the clerkship affect medical student interest in obstetrics and gynecology?

Methods

We conducted an anonymous, self-administered written survey of all third-year medical students rotating through a required obstetrics and gynecology clerkship from November 2006 to May 2007 at a single, large, urban medical university in the eastern United States. For content validity, survey questions were developed with input from obstetrics and gynecology faculty and residents, as well as recently graduated and current fourth-year medical students. Career interest in obstetrics and gynecology before the clerkship was assessed with the question, “What was your level of interest in ob/gyn (as a career choice) before this rotation?” and by using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not interested,” 2 = “slightly interested,” 3 = “moderately interested,” 4 = “very interested,” and 5 = “completely undecided”). In a similar fashion, students were asked about their level of career interest in obstetrics and gynecology at the time of survey distribution, which occurred during the last week of their 4-week clerkship. All medical students (N = 91) participating in the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship were eligible for this study.

We used univariate statistics to describe participant characteristics. We performed bivariate analysis and used χ2 analysis to explore factors associated with interest in pursuing obstetrics and gynecology as a career, including student factors, teaching factors, and experiential learning factors. Student factors assessed were male or female sex and the student's top 5 career choices. Teaching factors included 8 questions regarding faculty teaching and 15 questions regarding resident teaching. Experiential learning factors included 5 questions assessing number of breast and pelvic examinations performed and location of the examination (eg, operating room, labor and delivery ward, clinic), 12 questions assessing performance of specific procedural tasks during a cesarean delivery, and 13 questions assessing performance of specific procedural tasks during gynecologic surgery. One confounding variable—prior clerkships completed—was also assessed. Using bivariate analyses, we examined these factors for associations between preclerkship and postclerkship career interest. We also examined factors associated with changes in levels of career interest in obstetrics and gynecology before and after the clerkship. P ≤ .05 was statistically significant.

This study was approved by the School of Medicine Curriculum Committee Executive Subcommittee and was exempted by the institution's Institutional Review Board.

Results

Eighty-one of 91 students completed a survey (89% response rate); 33 were men, 46 were women, and 2 declined to reveal their sex. Students who were interested in considering a career in obstetrics and gynecology before the start of the clerkship were more likely to be women (P = .003) and more likely to also list pediatrics among their top 5 career choices (P = .011). Preclerkship obstetrics and gynecology career interest influenced the frequency of hands-on activities, including more frequent pelvic examinations performed in the operating room (P = .002). However, students were less likely to report having had experience with skin stapling and suctioning the airway of newborns during cesarean deliveries (P = .007 and P = .049, respectively).

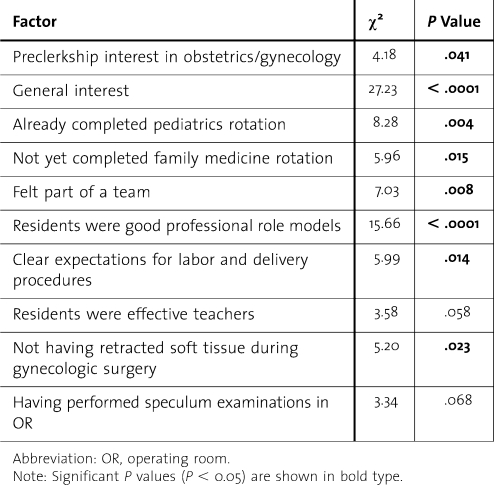

Preclerkship career interest was associated with postclerkship career interest (P = .041); however, postclerkship career interest in obstetrics and gynecology is associated with slightly different factors (table). Being “part of a team” increased the likelihood that students would report interest in an obstetrics and gynecology career at the end of the rotation (P = .008). Resident activities and students' perceptions of the residents were also associated with career interest at the end of the rotation. This included the perception that obstetrics and gynecology residents were “good role models of professional behavior” (P < .0001) and that residents had clearly expressed their expectations of the students' roles while in the labor and delivery suite (P = .014). Although not statistically significant, these students were also more likely to describe the residents as “effective educators” (P = .058).

Table.

Factors Associated With Postclerkship Career Interest in Obstetrics and Gynecology

In general, hands-on experience (suturing, using the Bovie instrument) was not associated with postclerkship career interest. Postclerkship career interest was associated with a lower likelihood of having had experience in retracting soft tissue during gynecologic surgery (P = .023). Although not statistically significant, performing more pelvic examinations in the operating room had some influence on career interest (P = .068). Students' sex, number of deliveries, and the teaching quality of the attending physicians were not associated with postclerkship career interest in obstetrics and gynecology.

Before the clerkship, 43 medical students (53%) had indicated interest in obstetrics and gynecology as a career; at the end of the clerkship, 54 (67%) had expressed interest in obstetrics and gynecology. Comparing the level of career interest before and after the clerkship, we noted that level of interest in obstetrics-gynecology increased for 56% (45 of 81) of participating students, remained the same for 30% (24 of 81), and declined for 14% (11 of 81). Although more women than men were interested in obstetrics and gynecology as a career both before (P = .027) and after (P = .014) the clerkship, men were more likely to show an increase in interest during the clerkship (P = .024). Aside from students' sex, having had more interaction with obstetrics and gynecology residents was associated with increased career interest (P = .011). Student perception of quality of teaching, number of deliveries, feeling part of a team, and having clear rotation expectations were not associated with change in level of career interest.

Hands-on experiences did not significantly affect career interest in obstetrics and gynecology. Students who had a preclerkship interest in obstetrics and gynecology were more likely to seek greater pelvic examination experience, which could explain the slight nonsignificant trend associating a higher number of pelvic examinations with postclerkship career interest. Students who described more interest in obstetrics and gynecology were less likely to have had other types of hands-on experiences, such as participation in cesarean deliveries, stapling skin, and suctioning the airway of the newborn during cesarean deliveries, and retracting soft tissue or bladder and using Bovie cautery in gynecologic surgeries. Students possibly felt less involved and more tangential during cesarean deliveries and viewed skin stapling or tissue retraction as lower-skill, less interesting tasks.

Discussion

Clerkship factors associated with greater postclerkship interest include a higher satisfaction with resident professional behavior and students' sense of inclusion in the clinical team. A larger number of study participants reported a career interest in obstetrics and gynecology at the end of the clerkship than at the beginning of the clerkship, with more men reporting an increase in interest postclerkship than preclerkship. Teaching attributes were associated with preclerkship career interest, suggesting that neither residents nor faculty favored, with more intensive or higher quality teaching, those students who wished to pursue obstetrics and gynecology.

Students' interactions with and perceptions of the residents were more consistently influential than either the quality or quantity of faculty interactions or the amount and type of participation in deliveries and surgical procedures. Students' feelings of being part of a team were likely the result of a sense of inclusion and camaraderie from the residents within that clinical team. The high association between perception of residents as good professional role models and postclerkship career interest suggests that students may be placing value on the personalities and characteristics of the practitioners and advanced learners in the specialty. Should a student choose to enter into the field of obstetrics and gynecology, residents would represent the most immediate colleagues and peers. When considering whether to pursue a career in obstetrics and gynecology, students may be making judgments regarding whether they share qualities, characteristics, and values with this group.

Students' perceptions of the residents' teaching behavior (eg, their inclusion of students in the clinical team, the clarity with which they communicated what they expected from the students, and their professionalism) were significantly associated with career interest at the end of the clerkship. Students' perception of the residents as “effective educators” trended toward significance, with a P value of .053.

Our study has several limitations. Our participants consisted of one class of medical students at a single medical school, and thus our results cannot be generalized to other institutions with clerkships differing in characteristics and structure.

While study participation was high (89%), we have no information about students who did not choose to participate and therefore we cannot assess for potential confounders. Our sample does have a slightly higher proportion of female students (57%) than the usual sex distribution in our medical school classes, which introduces the possibility of sampling bias. Despite our attempts to implement multiple methods of protecting participants' identity, the timing of survey completion—after a practice-based learning session and before the end of the clerkship—may have introduced some reporting bias. However, the fact that 14% of the students indicated that their interest in obstetrics and gynecology had decreased during the clerkship suggests that this was not the case. Time and funding limitations did not allow us to compare these clerkship experiences and students' interest levels with those of other clerkships and other specialties. Finally, owing to the anonymous nature of the surveys, we could not follow up with participants to assess their final career choices and determine whether their postclerkship interest was associated with entry into the field of obstetrics and gynecology. We do know that 9 female students from that class did match in obstetrics and gynecology.

Our study contributes to the literature in the field because, to our knowledge, no prior study has examined with the same level of detail the association between clerkship experience and specialty choice; instead, prior research has focused primarily on students' characteristics and the number and type of other clerkships completed.

Conclusion

Residents and faculty should make students feel that they are part of the clinical team. Helping clerkship students to become invested in the care of the patients in the obstetrics and gynecology service may in turn generate greater student interest for the specialty. This can be achieved by providing the student with an active and contributing role in the clinical team as well as allowing the student to participate more directly in patient examinations and procedures.

We offer 2 recommendations. Obstetrics and gynecology clerkship directors and residency program directors need to emphasize to residents their role as educators and professional role models for medical students. As suggested by leaders of the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, medical student educators—residents as well as attending physicians—need to be rewarded and recognized for their contributions and efforts.1,3,20 While at first glance faculty educators may be discouraged that their interactions with students were not as significant as students' interactions with residents, faculty can continue to serve as teachers and educators to residents by helping them to develop their teaching skills and styles as they further their learning of the field of obstetrics and gynecology. Residents may also benefit from attending training workshops on how to be effective teachers. Student clerkship evaluations have been shown to significantly improve after residents participate in teaching skills workshops.11 Future research is needed to explore whether these various efforts to improve the students' clerkship experiences will lead to more students pursuing a career in obstetrics and gynecology.

Footnotes

Judy C. Chang, MD, MPH, is Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Michele R. Odrobina, MD, is Practicing Physician, Obstetrics and Gynecology, at Medina Memorial Health Care System; and Kathleen McIntyre-Seltman, MD, is Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, and Advisory Dean, Office of Student Affairs, at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Dr Odrobina was participating in her residency training during the time of the study and performed this study as her senior residency research project.

Funding: This project was supported by funding from the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh. Dr Chang's efforts were sponsored by the BIRCWH award (NIH/NICHD 5 K12 HD43441-04) and the Agency for Research Healthcare and Quality (1 K08 HS13913-01A1).

References

- 1.Gibbons J. M., Jr Springtime for obstetrics and gynecology: will the specialty continue to blossom? Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(3):443–445. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire Results: All School Report. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bienstock J. L., Laube D. W. The recruitment phoenix: strategies for attracting medical students into obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5, pt 1):1125–1127. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000162532.62399.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke W. M., Williams J. A., Fenner D. E., Hammoud M. M. The obstetrics and gynecology clerkship: building a better model from past experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(5):1772–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Signer M. M., Beran R. L. Results of the National Resident Matching Program for 2003. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):653–656. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Signer M. M., Beran R. L. National Resident Matching Program. Results of the National Resident Matching Program for 2004. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):610–612. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Residency Matching Program. Results and Data: 2007 Main Residency Match. Washington, DC: National Residency Matching Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin M. A., Daugherty S. R., Rose W. H., Goodman L. J. Specialty choice during the clinical years: a prospective study. Acad Med. 1993;68(10 suppl):S55–S57. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199310000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellsbury K. E., Carline J. D., Irby D. M., Stritter F. T. Influence of third-year clerkships on medical student specialty preferences. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1998;3(3):177–186. doi: 10.1023/A:1009748211832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gariti D. L., Zollinger T. W., Look K. Y. Factors detracting students from applying for an obstetrics and gynecology residency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammoud M. M., Stansfield R. B., Katz N. T., Dugoff L., McCarthy J., White C. B. The effect of the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship on students' interest in a career in obstetrics and gynecology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(5):1422–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fogarty C. A., Bonebrake R. G., Fleming A. D., Haynatzki G. Obstetrics and gynecology—to be or not to be: factors influencing one's decision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(3):652–654. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00880-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert E. M., Holmboe E. S. The relationship between specialty choice and gender of U.S. medical students, 1990–2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):797–802. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metheny W. P., Blount H., Holzman G. B. Considering obstetrics and gynecology as a specialty: current attractors and detractors. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(2):308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanfey H. A., Saalwachter-Schulman A. R., Nyhof-Young J. M., Eidelson B., Mann B. D. Influences on medical student career choice: gender or generation? [discussion in Arch Surg. 2006;141(11):1094; erratum in Arch Surg. 2007;142(2):197; comment in Arch Surg. 2007;142(11):1110] Arch Surg. 2006;141(11):1086–1094. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnuth R. L., Vasilenko P., Mavis B., Marshall J. What influences medical students to pursue careers in obstetrics and gynecology? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(3):639–643. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz R. W., Haley J. V., Williams C., et al. The controllable lifestyle factor and students' attitudes about specialty selection. Acad Med. 1990;65(3):207–210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199003000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz R. W., Jarecky R. K., Strodel W. E., Haley J. V., Young B., Griffen W. O., Jr Controllable lifestyle: a new factor in career choice by medical students. Acad Med. 1989;64(10):606–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard M. H., Autry A. M., Brown H. L., et al. A multicenter study to determine motivating factors for residents pursuing obstetrics and gynecology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1835–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ernest J. M., Kellner K. R., Thurnau G., Metheny W. Rewarding medical student teaching. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):853–857. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00256-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]