Abstract

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) have partnered to initiate the Pediatrics Milestone Project to further refine the 6 ACGME competencies and to set performance standards as part of the continued commitment to document outcomes of training and program effectiveness.

Intervention

Members of the Pediatrics Milestone Project Working Group searched the medical literature and beyond to create a synopsis of models and evidence for a developmental ontogeny of the elements for 52 subcompetencies. For each subcompetency, we created a series of Milestones, grounded in the literature. The milestones were vetted with the entire working group, engaging in an iterative process of revisions until reaching consensus that their narrative descriptions (1) included all critical elements, (2) were behaviorally based, (3) were properly sequenced, and (4) represented the educational continuum of training and practice.

Outcomes

We have completed the first iteration of milestones for all subcompetencies. For each milestone, a synopsis of relevant literature provides background, references, and a conceptual framework. These milestones provide narrative descriptions of behaviors that represent the ontogeny of knowledge, skill, and attitude development across the educational continuum of training and practice.

Discussion

The pediatrics milestones take us a step closer to meaningful outcome assessment. Next steps include undertaking rigorous study, making appropriate modifications, and setting performance standards. Our aim is to assist program directors in making more reliable and valid judgments as to whether a resident is a “good doctor” and to provide outcome evidence regarding the program's success in developing doctors.

The ACGME Outcome Project Evolves Into the Milestone Project

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Outcome Project shifted the focus of the accreditation aspects of residency training from the process of education to the outcomes of programs. The Assessment Toolbox, a product of collaboration between the ACGME and the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) was offered to the graduate medical education (GME) community as a resource and to stimulate further work on assessment.1,2 Despite the availability of this and other resources, individuals and institutions continue to struggle to define the optimal method for measuring achievement in the competencies.3 Hence, the work of the ACGME Milestone Project, which seeks to take the next steps in advancing educational outcome assessment in GME, is of critical importance. These benchmarks, or milestones of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA), will document increasing mastery of the 6 competencies.2,4 The ACGME goal in creating milestones for every specialty is to ensure that programs and the ACGME will collectively be able to certify to the public that the residents are competent to practice in their specialty without direct supervision at the end of their training.

The Pediatrics Milestone Project Begins

In early 2009, the ACGME and the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) jointly launched the Pediatrics Milestone Project. The goals of the project are to (1) reframe and further define the 6 competencies in the context of the specialty of pediatrics, (2) identify markers of achievement along the continuum of GME, and (3) identify tools that could be embraced by the pediatric community as meaningful measures of performance. We assembled a 10-member working group (2 of the 10 were staff members), composed of members of the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD), 1 member of the Medicine-Pediatrics Program Directors Association (MPPDA), 2 representatives of the ACGME, and 1 resident member. We also created an advisory board, whose members were selected from the sponsoring organizations and from other highly regarded national leaders in medical education, to guide us in our work, which began in April 2009.

Foundational Work for the Project: Guiding Principles and Conceptual Considerations

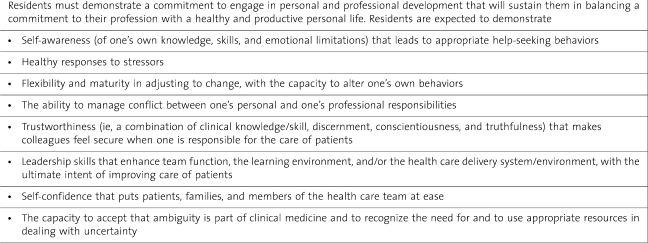

The first task of the Pediatrics Milestone Project Working Group (the authors of this article) was to construct Guiding Principles and Conceptual Considerations. These foundational documents, drafted in May 2009, provided the scaffolding for the working group, guiding us in both the approach to the work and in the actual construction of the milestones. The importance of defining the continuum, from undergraduate medical education (UME) through GME to the continuous professional development (CPD) of Maintenance of Certification (MOC), is reflected as a central goal of the working group in both of these documents (tables 1 and 2). An example of a key guiding principle is that “the ACGME competencies are necessary, but may not be sufficient, in defining milestones for professional formation of pediatricians.” Although not part of the original charge, the working group saw this reflective process to identify implicit subcompetencies that should be made explicit as the first essential step in addressing the refinement of the competencies for our specialty. As such, we began an ongoing dialogue with the membership of APPD at their spring 2009 meeting. Attendees were asked to consider possible subcompetencies that are not explicitly articulated in the current ACGME competencies. Coding responses and discerning major themes produced the personal and professional development subcompetencies displayed in table 3, which were added to the subcompetencies included in the 6 ACGME competency domains of our program requirements.

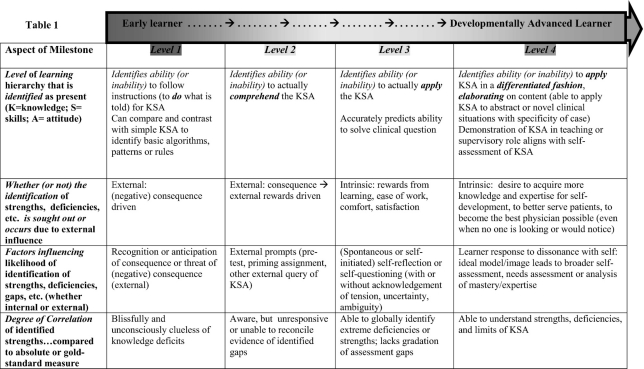

Table 1.

Table 1 is meant to serve as a guide for the continuum of learner identification of level of knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSA), including deficiencies and areas of strength. Because the acquisition of achievement of this milestone involves multiple areas of development, achievement of this milestone may be best determined by achievement across multiple elements. Scoring of this item may not result in the simple sum of scores (progress) within each continuum (row in Table 1), rather there may be compensatory elements (content achieved in rows) that "make up" for slower progress in other elements (content in rows)

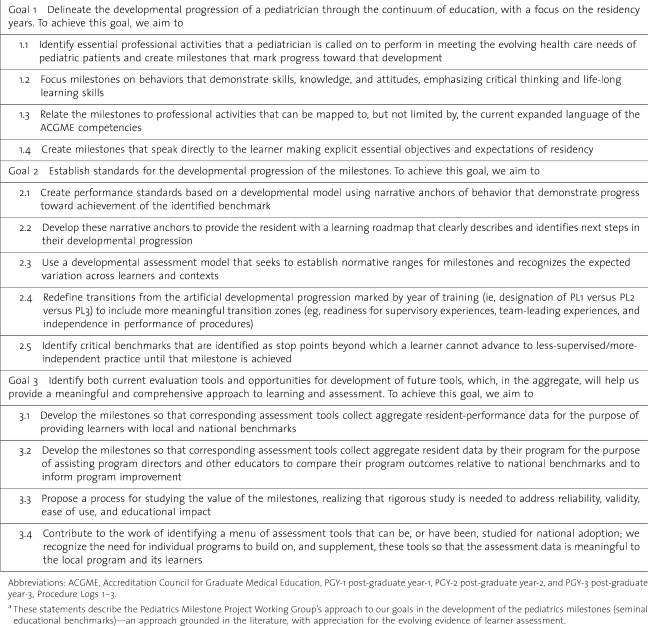

Table 2.

Conceptual Considerations in the Framing of the Pediatrics Milestonesa

Table 3.

Personal and Professional Development

A key area of focus for the conceptual considerations was a developmental model, both in creating the milestones and in setting performance standards. We anticipated creating narrative anchors of behaviors to serve as a learning roadmap for trainees and to contribute to the establishment of normative ranges of behaviors to help educators define performance standards, recognizing that there would be some variation across learners and contexts.

Establishing the Scholarly Approach for the Development of the Pediatrics Milestones

The Pediatrics Milestone Project Working Group's approach was grounded, in part, by Glassick's second standard for assessing scholarship, calling for adequate preparation whereby scholars show their understanding of existing scholarship in the field.5 For our work, this translated to grounding the milestones in the literature. Specifically, we searched the literature for conceptual frameworks6—theories or models that represent or inform the approach to the developmental progression of KSA within a subcompetency.

In this search, we sought the ontogeny of behaviors that would represent the does level in the Miller pyramid.7 Although difficult, it was important to identify and define constructs, or observable traits that help to represent components of real world performance, for each subcompetency considered. In addition, case specificity,8 one's inability to translate learner performance from one context to another, contributed a layer of complexity to the design of the milestones. The complexity of case specificity contributed an additional challenge to the design of the milestones. Therefore, we intentionally wrote the milestones as generic items with the addition of examples of behavioral descriptors in a specific clinical setting, providing real-world context. We recognize that assessment using the specific examples offered in each milestone would yield outcomes that may not be transferable to another context.8

In searching the literature to inform the development of the milestones, the primary authors came to appreciate the paucity of evidence for defining the ontogeny of the development of KSAs for many milestones. This resulted in an iterative process of (1) piecing together various theories and models to address the different facets of a subcompetency, (2) translating the models and theories gleaned from the literature into behaviors that marked development over time, (3) testing the sequence of behaviors against our own empirical evidence gained from years of working with learners, and (4) often starting the process over again when vetting within our working group added a different lens to the primary author's work. This resulted in the construction of each milestone through a process using a “succession of lenses,” as Harris9 describes in the deliberative inquiry approach to curriculum design. This iterative approach of searching the literature, building on relevant theories and models, and then revising to accommodate the perspectives or lenses of the working group is a critical contribution to the construct validity of the Pediatrics Milestone Project.10

Construction of a Pediatrics Milestone

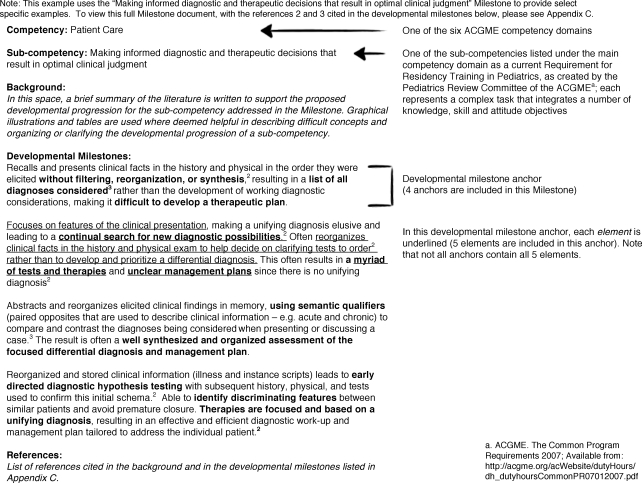

For each subcompetency, we created a milestone document that features a background or synopsis of the literature with references and a sequence of narrative descriptions of observable behaviors at advancing levels of development across the educational continuum of training and practice. Of note, we intentionally did not label (eg, novice, competent) these descriptors, wanting the focus to be on the behavior and not on the label. Illustration of the format for the Pediatrics Milestones is shown in the figure The Anatomy of a Pediatrics Milestone.

Figure.

Anatomy of a Pediatrics Milestone

Note: This example uses the Making Informed Diagnostic and Therapeutic Decisions That Result in Optimal Clinical Judgment milestone to provide select specific examples. To view this full milestone document, with the references 2 and 3 cited in the developmental milestones below, please see Appendix E online.

Initial Work in the Development of a Pediatrics Milestone

As discussed in the section on scholarship, authors initiated the development of milestones through a thorough literature search to identify relevant theories or models that would help to identify a sequence of observable behaviors that would illustrate the essential KSA embodied in the specific subcompetency.

For example, in the Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) subcompetency of “identify strengths, deficiencies and limits in one's knowledge, and expertise” (see appendix A online), the primary author first looked at literature regarding residents' abilities to identify their own level of understanding, knowledge, and expertise. The exploration of the literature on this subject reached back to the original theory constructed by John Dewey,11 moved through the learning theories of Kolb,12 and explored the more recent literature by Davis13 regarding the significant limitations to self-assessment.

As a second step, the primary author then reframed what was gleaned from the literature in the context of clinical practice to make it meaningful to learners, faculty, and program directors. For example, in the PBLI subcompetency discussed above, the author used a set of questions that stimulates specific elements of critical thinking14 when describing progression of developmental milestones about “the learner's ability to identify strengths, deficiencies and limits in one's knowledge and expertise” (see appendix A online).

Using the multiple literature sources searched, the experience with learners at different levels of education and training, and the conceptual framework that had been formed, the authors' next step was to construct a developmental progression of the individual elements of the developmental milestones (table 2 of appendix A). Careful consideration was given to constructing the spectrum of behaviors for each element of a given subcompetency. This spectrum was ultimately the judgment of the primary author, based on her understanding of the subject of self-assessment and other relevant literature and experience with learners at each developmental stage. Even with later vetting of these judgments with the working group, it became clear early in this process that the initial iteration of milestones would require expert input regarding these judgments.

For the more complex milestones, an example was often constructed to illustrate each developmental level. Where possible, a consistent context for these examples was used along the continuum of levels within a given milestone to aid in clarity. It is hoped that such examples may be built on as we move forward and compile resources, such as standardized patients or video recordings to train and calibrate raters. These same resources could be used for faculty development efforts.

At the end of these first 3 steps, the primary author would then develop a written document, the components of which are illustrated in the figure.

Working Group Vetting of a Pediatrics Milestone

Once the primary author had finished the initial development of a milestone, this document was distributed to the entire working group, and the process of vetting took place during every two weeks phone calls and occasional face-to-face meetings during the past 18 months.

In vetting the milestones, the working group applied a modified standard-setting approach.15 In this process, judgments about scoring of the developmental milestone anchors within each milestone are constantly compared to the known or familiar population of learners as they develop from undergraduate medical education through the level of being ready to perform without direct supervision (graduating third-year residents) and beyond into practice. This included defining and describing minimum cutoffs for acceptable beginning-intern performance and the endpoints for GME, at which the absolute minimum readiness to practice without direct supervision is achieved.

Other important considerations during the vetting process are included in paragraphs 1 through 5 below.

-

Close examination of the developmental milestone anchors in the milestone document reveals that each embraces a number of different behavioral elements. Careful consideration was given to these clusters of elements and whether they develop synchronously or asynchronously, whether some elements are ordinal (yes or no; present or absent), or whether some elements take large jumps across anchors versus changing in small, granular ways within a given anchor or among anchors.16 The nature of developmental progression for each element was important to consider because not all elements would progress along their specific trajectories at the same rate. Furthermore, all elements may not be measurable in quantitative terms. Much like the Denver Developmental Screening Test for assessing elements of fine motor, gross motor, language, and social development of children,17 progress along 1 element of development may take place at a different rate than progress on other elements. The measure of the learner's performance may also fall between specified behavioral descriptions because the milestones represent points along a continuum.

For example, we found in the milestone addressing Competency in the Performance of Procedures that development in some cognitive aspects of procedures (knowing some of the steps it takes to perform a procedure, such as contraindications, indications, risks, benefits, etc) may develop before the psychomotor procedural skills are developed.

-

The working group considered whether elements within a developmental milestone anchor were required elements and were necessary in defining a particular developmental stage.

For example, the milestone of Making Informed Diagnostic and Therapeutic Decisions That Result in Optimal Clinical Judgment (Appendix C online) speaks directly to the concept of clinical reasoning, on which much has been written in the literature.18–21 Incorporating well-studied and delineated concepts from this literature was thought to be a requirement and necessary for defining particular developmental stages, and this milestone includes a number of these concepts, including analytic reasoning to describe the earliest stage in clinical reasoning22 and the use of semantic qualifiers18 (paired opposites to describe clinical information, such as acute and chronic) and illness scripts (narrative scripts in which the characteristic features of specific illnesses form clinical patterns in memory) to describe components of more advanced stages.21,23

The working group also considered whether some behavioral elements within a given cluster of a milestone are compensatory in nature and thus, if present, would allow a rater to assign that particular anchor level, even if other elements of that level were not met. The subcompetency addressing patient and family education provides an illustration of where some elements of an anchor might not be met but the resident would still be able to pass to the next developmental level. For example, if a resident struggles with oral communication with families, often finding it difficult to translate complex medical concepts into simple language that can be understood by the family, but that resident has very strong skills in graphical representation of information, that resident may be very effective in explaining the diagnosis and treatment options through drawings or other graphical representations of the situation. Thus, this resident could achieve a milestone that describes oral communication skills leading to patient and family understanding, without the possession of superior oral communication skills. Caution should be applied when allowing for compensatory scoring; that is, one should be sure that what one is considering as compensatory is truly part of the construct of that individual milestone and not a character trait, impression, or other subjective element giving favor to the resident in the eyes of the assessor (a halo effect).24

The working group next reviewed all developmental milestone anchors to be sure they were written as observable or demonstrable (even if not measurable) statements. These anchors may or may not relate directly to the learning objectives for an associated curriculum. A simple Tylerian approach, where evaluation is linked to specified curricular learning goals and objectives, was not desired.25 Many subcompetencies address learning that takes place through the hidden (or implicit) curriculum or through the explicit curriculum. However, even in the latter case, the objectives themselves may not be explicitly stated. Therefore, although people are accustomed to assessing discrete objectives, we appreciate that, for the milestones to be meaningful, it is necessary to embrace and capture the complexity that is present in performing and assessing these complex tasks. The working group, therefore, acknowledged the importance of the milestones as a roadmap to learning for residents. Although the milestones are being constructed for the purpose of program outcomes, they are intended to measure the individual resident performance and, as such, should be carefully written to be useful as a guide to the learner. The working group thus reflected on how the milestone document, especially the developmental anchors, were written to speak to learners in an understandable, meaningful, and nonthreatening manner.

For some milestones, the working group looked for critical transition points in the middle section of the range of developmental milestone anchors, from the beginning intern to the graduating resident. These stopping points reflect the developmental level that would need to be reached before the resident could perform certain duties, such as supervise more junior residents or care for patients without direct (in-house or immediately available) supervision.

An example of such a stopping point is illustrated in the Trustworthiness milestone (Appendix B, box), where a specific level of discernment or conscientiousness26 (terms defined in the milestone) must be met before the resident could move to a less directly supervised setting.

Further Refinement of the Pediatrics Milestone by the Primary Author

After thoughtful vetting by the entire working group, the primary author would revise the milestone based on written (e-mail) review and input from discussion (via conference call or face-to-face meeting). The process of discussion, editing, and revising was repeated for many milestones, illustrating the highly iterative nature of our work.

box Pediatrics Milestone Project Working Group Principles

The working group of the Pediatrics Milestone Project seeks to (1) delineate the developmental progression of a pediatrician through the continuum of education, with a focus on the residency years; (2) establish standards for that developmental progression; and (3) identify both current evaluation tools and opportunities for development of future tools that in the aggregate will help us provide a meaningful and comprehensive approach to learning and assessment.

The outcome of the Pediatrics Milestone Project will be the first step in what we hope will be an iterative process of quality improvement in residency training within the evolving context of the continuum of medical education. It represents a starting point rather than an end point, a new way of thinking about medical education using a developmental approach.

Below are critical assumptions and beliefs that are central to helping us navigate the Pediatrics Milestone Project:

Creating the Milestones

Our ultimate goal and driving force is meeting societal needs for quality patient care and safety through better education and training as measured, where possible, through patient care outcomes.

The Pediatrics Milestone Project will focus on core skills but recognizes the pediatrician of tomorrow will need some flexibility in training to achieve skills in the context of their specific career paths.

We will engage the patient to inform the development of the milestones.

The Pediatrics Milestone Project strives to develop a work product that recognizes the natural tension between the values of autonomy and personal ownership associated with the privilege of caring for patients and the increasing focus on interdependence and teamwork necessary for optimal care.

Professional formation requires the development of behaviors through deliberate practice, which define a “good doctor” as well as longitudinal assessment to ensure that these behaviors become habits.

Embedding the Milestones in the Context of Medical Education

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies are a necessary, but not sufficient, framework for our work. For example, not all competencies are created equal, and they are inseparable in real world practice.

In developing the products of the Pediatrics Milestone Project, we will look to the continuum of undergraduate medical education, Graduate Medical Education, and Continuing Professional Development to inform our work.

Assessing the Milestones

Evaluation and assessment of residents is optimized when it is practical, flexible, and done with, rather than to, the learner.

In the assessment of performance, there needs to be balance between deconstructing the complex tasks of a physician into discrete learning objectives and reconstructing these objectives to capture how they are integrated into a complex task.

Implementing the Milestones

The Pediatric Milestone Project will strive to develop work products that can be successfully implemented by all program directors, other educators, and learners at the grassroots level.

We will need to incorporate ongoing assessment of the project into the implementation process.

We will engage stakeholders throughout the pediatrics and lay communities into the implementation phase.

Emerging Themes and Discoveries

The development of each milestone prompted the working group to consider the curriculum design that would prepare a pediatric resident to make progress in demonstrating the desired behaviors captured in the milestones. Often, the chosen conceptual framework for the elements of the milestones was derived from published literature describing the rationale for a curricular design.

-

There were consistent themes in the developmental ontogeny of many milestones, elaborated in a recent article by the Pediatrics Milestone Project Working Group.27 Some are listed here:

a. The developing physician moves from a dependent learner to a more independent learner.

b. The developing physician becomes more intrinsically motivated or directed as he or she matures.

c. The development of an appreciation of the need for teamwork and dependency on resources outside of self allows the mature learner to practice without direct supervision (but with awareness of the need for assistance).

d. There is a developmental progression of comfort with uncertainty and development of effective strategies to manage ambiguity.

It is important to make explicit the implicit goal that the development of personal and professional growth is an essential domain for the physician entrusted with the care of children and adolescents.28

The elements of one subcompetency often overlap with the elements of another, making the achievement of one subcompetency interdependent on the other.

None of the milestones, by themselves, will speak to the consistency or habit with which a resident demonstrates the behaviors of that milestone. Individual milestones capture observable behaviors for only 1 specified time and context. Consistency, habits, and professionalism are optimally inferred from performance data across a number of contexts and observations over time.

Challenges and Next Steps

Although every attempt was made to construct the pediatrics milestones using the best evidence for assessment of the competencies, the working group's expertise is limited by the education and experiences of the group and the literature we explored. Outcome evidence or assessment results that provide the type of reassurance that residents, programs, the ACGME, and the public expect will require further work on the milestones themselves and on the approach to measurement and reporting. The Pediatrics Milestone Working Group looks forward to the opportunity to collaborate with a variety of experts to improve this first iteration of the pediatric milestones. We hope to consult content experts for the more complex milestones, where the ontogeny of skill development was difficult to frame. We also look forward to engaging in discussion with a newly appointed ACGME Advisory Group on Assessment that is dedicated to the Milestone Project.

A guiding principle that directed our development of the behavioral narrative anchors stated, “in the assessment of performance, there needs to be balance between deconstructing the complex tasks of a physician into discrete learning objectives and reconstructing these objectives to capture how they are integrated into a complex task.” The latter presented the greatest challenge. To accomplish this in measurement and reporting efforts, we plan to embrace the complexity and capture the continuum of behaviors that underlie the developmental progression through a series of developmental milestones rather than focus only on the 4 to 5 milestones in a series as discrete anchors.

Another challenge that we face is reporting achievement of milestones. Our plan is to weigh all of the elements of a milestone that describe a given subcompetency, so that, rather than reporting yes or no to the question of achievement, we will be able to report proximity to a target of the aggregated elements within a series of developmental milestones. In a subsequent article, we will share ideas for next steps as we work to not only improve the pediatrics milestones but also to hopefully contribute in a meaningful way to the milestones work for many other specialties through the lessons learned from our own work.

Footnotes

Patricia J. Hicks, MD, is Director of the Pediatric Residency Program at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and Professor of Clinical Pediatrics in the Department of Pediatrics at University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Daniel J. Schumacher, MD, is a Clinical Fellow in Emergency Medicine at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; Bradley J. Benson, MD, is Med-Peds Program Director at the University of Minnesota Amplatz Children's Hospital and Director of the Division of General Internal Medicine and Associate Professor of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine; Ann E. Burke, MD, is Director of the Pediatric Residency Program at Wright State University, Boonshoft School of Medicine and in the Department of Pediatrics, at the Dayton Children's Medical Center; Robert Englander, MD, MPH, is Senior Vice President of Quality and Patient Safety at the Connecticut Children's Medical Center and Professor of Pediatrics at University of Connecticut School of Medicine; Susan Guralnick, MD, is designated institutional official (DOI) and Director of Graduate Medical Education at Winthrop University Hospital, Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Winthrop University Hospital, and Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Stony Brook University School of Medicine. Stephen Ludwig, MD, is designated institutional official (DOI) and Chairman of Graduate Medical Education at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and Professor of Pediatrics and Professor of Emergency Medicine at University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Carol Carraccio, MD, MA, is Associate Chair for Education at University of Maryland Hospital for Children, and Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland School of Medicine.

The working group would like to thank Ms Lisa Johnson and Dr Jerry Vasilias for their support and constant encouragement of the group. Their commitment to the Milestones Project has been invaluable.

Editor's Note: The online version (63.5KB, doc) of this article contains 3 appendices (137KB, doc) on practice-based learning, personal and professional development, and patient care (90KB, doc) , respectively.

References

- 1.[ACGME/ABMS] Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education/American Board of Medical Specialties. Toolbox of assessment methods. http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/assess/Toolbox.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2010.

- 2.[ACGME] Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The ACGME outcome project: an introduction. http://www.acgme.org/outcome. Accessed June 1, 2010.

- 3.Lurie S. J., Money C. J., Lyness J. M. Measurement of the general competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):301–309. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasca T. CEO's Welcoming Address at the ACGME Annual Educational Conference, 2010. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/newsReleases/newsRel_3_23_10_1.asp. Accessed June 1, 2010.

- 5.Glassick C. E. Boyer's expanded definition of scholarship, the standards of assessing scholarship and the elusiveness of the scholarship of teaching. Acad Med. 2000;75(9):877–880. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordage G. Conceptual frameworks to illuminate and magnify. Med Educ. 2009;43(4):312–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller G. E. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(suppl 9):563–567. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norman G., Bordage G., Page G., Keane D. How specific is case specificity? Med Educ. 2006;40(7):618–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris I. B. Deliberative inquiry: the art of planning. In: Short E. C., editor. Forms of Curriculum Inquiry. Albany, NY: State University of New York; 1991. pp. 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downing S. M. Validity: on the meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37(9):830–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewey J., editor. How We Think? A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. Boston, MA: DC Heath & Co; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolb D. A. Experiential Learning as the Science of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis D. A., Mazmanian P. E., Fordis M., Van Harrison R., Thorpe K. E., Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King A. Designing the instructional process to enhance critical thinking across the curriculum. Teach Psychol. 1995;22(1):13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cizek C. J., editor. Setting Performance Standards: Concepts, Methods and Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downing S. M., Yudkowsky R. Assessment in Health Professions Education. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. Developmental surveillance and screening of infants and young children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):192–196. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bordage G. Prototypes and semantic qualifiers: from past to present. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1117–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coderre S., Mandin H., Harasym P. H., Fick G. H. Diagnostic reasoning strategies and diagnostic success. Med Educ. 2003;37(8):695–703. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen J. L. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(21):2217–2225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt H. G., Rikers R. M. How expertise develops in medicine: knowledge encapsulation and illness script formation. Med Educ. 2007;41(12):1133–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt H. G., Boshuizen H. P. A. On acquiring expertise in medicine. Educ Psychol Rev. 1993;5(3):205–221. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt H. G., Norman G. R., Boshulzen H. P. A cognitive perspective on medical expertise: theory and implications. Acad Med. 1990;65(10):611–621. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199010000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downing S. M., Yudkowsky R. Validity and Its Threats: Assessment in Health Professions Education. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stufflebeam D. L., Shinkfield A. J. Evaluation Theory, Models and Applications. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy T. J., Rehehr G., Baker G. R., Lingard L. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008;83(suppl 10):S89–S92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Englander R., Hicks P., Benson B., et al. Pediatric milestones: a developmental approach to the competencies. Pediatrics. 2010. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Cooke M., Irby D. M., O'Brien B. C. Educating Physicians—A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]