Abstract

Background

The provision of high-quality clinical care is critical to the mission of academic and nonacademic clinical settings and is of foremost importance to academic and nonacademic physicians. Concern has been increasingly raised that the rewards systems at most academic institutions may discourage those with a passion for clinical care over research or teaching from staying in academia. In addition to the advantages afforded by academic institutions, academic physicians may perceive important challenges, disincentives, and limitations to providing excellent clinical care. To better understand these views, we conducted a qualitative study to explore the perspectives of clinical faculty in prominent departments of medicine.

Methods

Between March and May 2007, 2 investigators conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with 24 clinically excellent internal medicine physicians at 8 academic institutions across the nation. Transcripts were independently coded by 2 investigators and compared for agreement. Content analysis was performed to identify emerging themes.

Results

Twenty interviewees (83%) were associate professors or professors, 33% were women, and participants represented a wide range of internal medicine subspecialties. Mean time currently spent in clinical care by the physicians was 48%. Domains that emerged related to faculty's perception of clinical care in the academic setting included competing obligations, teamwork and collaboration, types of patients and productivity expectations, resources for clinical services, emphasis on discovery, and bureaucratic challenges.

Conclusions

Expert clinicians at academic medical centers perceive barriers to providing excellent patient care related to competing demands on their time, competing academic missions, and bureaucratic challenges. They also believe there are differences in the types of patients seen in academic settings compared with those in the private sector, that there is a “public” nature in their clinical work, that productivity expectations are likely different from those of private practitioners, and that resource allocation both facilitates and limits excellent care in the academic setting. These findings have important implications for patients, learners, and faculty and academic leaders, and suggest challenges as well as opportunities in fostering clinical medicine at academic institutions.

Introduction

Patients seek care from physicians who are highly skillful and practice in a system that is safe and accessible.1,2 Although clinical excellence is important to patients regardless of where they seek to receive their care, some patients may seek clinical care in an academic institution because of the belief that academic physicians possess expertise or access to testing that is not available to physicians practicing in a nonacademic setting.3,4 Academic physicians who are highly clinically active report lower job satisfaction and a lesser commitment to stay at academic medical centers (AMCs), largely because the missions and reward systems in these settings are weighted heavily toward research as opposed to the provision of exceptional patient care.5 Excellent patient care, while part of the academic mission, is thought to contribute less to academic promotion, probably because it has not been defined and is not systematically measured, thereby inhibiting reward or recognition along this domain.6–11

One of the major goals of AMCs is to train and inspire the next generation of doctors to meet the needs of society.12−,14 Understanding how clinical care is perceived by academic clinicians may provide important insights into factors that can be leveraged to ensure that academic institutions continue to recruit and retain the most excellent clinically active physicians to provide high-quality care that patients seek, collaborate with researchers, and lead clinical program development, including building effective and efficient models of care and role models for learners.

We conducted this qualitative study to explore academic clinicians' perspectives about the advantages and challenges in providing clinical care in AMCs.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative method was selected to explore this content area and to generate hypotheses. Individual one-on-one interviews that permit exploration in greater depth may be possible with closed-ended scales, surveys, or even focus groups.

Study Sampling

Through purposive sampling, we recruited physicians with reputations for being the most clinically excellent within the top 10 departments of medicine according to the 2006 rankings from U.S. News & World Report.15 The department chairs at these 10 institutions were asked to name 5 physicians in their department who were judged to be the most clinically excellent. To help with their selection process, the following was included in the request: “In considering this, it may help to think about which of your faculty you would ask to care for a close family member who was ill (with a diagnosis within this physician's area of expertise).” From the lists of physicians, we randomly selected 3 physicians from each AMC to interview using www.random.org. If any of these physicians were unavailable or declined participation, we proceeded to the next physician from that institution on the random order list.

The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center approved the study.

Data Collection

From March to May 2007, 2 investigators conducted audiotaped, semistructured interviews lasting about 30 minutes with participants by phone. The interviewer began by asking closed-ended questions that collected demographic information, such as division and academic rank, before switching to open-ended questions. Participants were asked if they believed there was a difference in excellent clinical care between AMC and private practice, and to describe ways in which clinical excellence is different and ways they believed it was the same. The interviewers, trained in qualitative interviewing techniques, used reflective probes to encourage respondents to clarify and expand their statements. All interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

We analyzed transcripts using an “editing organizing style,” a qualitative analysis technique in which researchers search for “meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.”16 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data, as opposed to the application of a pre-existing template. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts, generated codes to represent the informants' statements, and created a coding template. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators successfully reached consensus after reviewing and discussing each other's coding. ATLAS.ti 5.0 software (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) was used for data management and analysis. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Following accepted qualitative methodology, we discontinued sampling after 24 interviews, when it was determined that new interviews yielded confirmatory rather than novel themes, a process called achieving thematic saturation.16 Our sample is consistent with other qualitative studies.17−,20

Results

Informant Sampling and Respondent Demographics

Two department of medicine chairs did not respond to 3 requests for the names of the most clinically excellent physicians among their faculty. Of the 40 names provided by the other 8 chairs, 24 (3 from each AMC) were randomly selected for the study. Of these, 2 individuals from 2 separate institutions were not willing to allocate time for participation. At both institutions the next physician randomly selected agreed to participate, resulting in 24 of 26 (92%) physicians approached about participating in the 30-minute interviews.

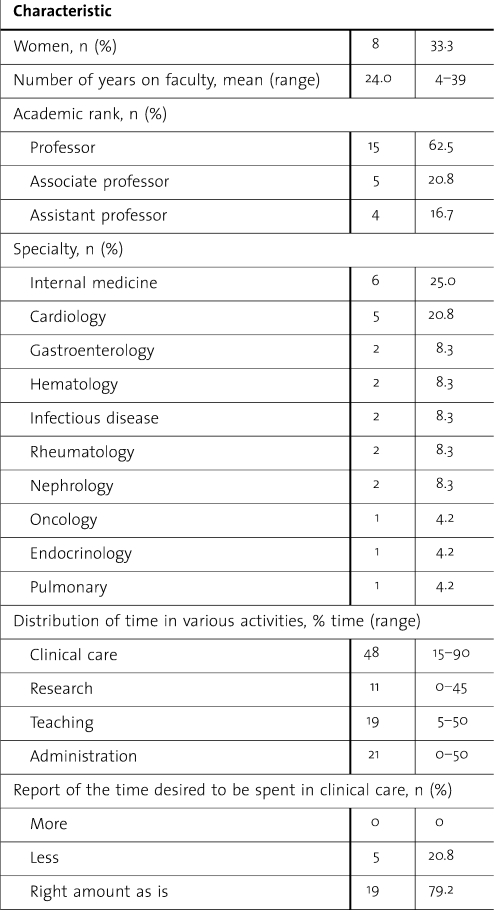

The majority (83%) of the participating physicians were senior faculty at the associate professor or professor ranks, one-third (33%) were women, and a diverse range of subspecialties within internal medicine was represented (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 24 Clinically Excellent Physicians Interviewed About Clinical Excellence From 8 Academic Institutions With Highly Rated Departments of Medicine

Overall Assessment

When asked specifically about whether they believed clinical excellence is the same or different in academic and nonacademic clinical settings, the opinions were mixed: 13 (54%) believed they were different, 2 (8%) claimed they are identical, and 9 (38%) acknowledged that there are similarities and differences in the realization of clinical excellence in these distinct settings. Open-ended follow-up questions stimulated elaborations on impressions and the detailed views described next.

Results of Qualitative Analysis

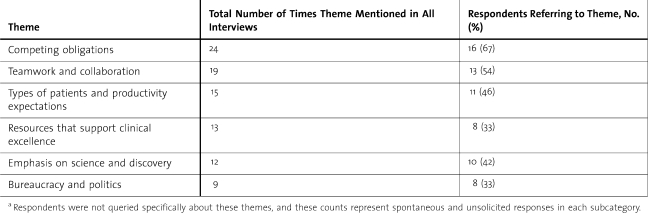

The commentaries of the physician informants were categorized into 6 major themes: competing obligations, teamwork and collaboration, the types of patients and productivity expectations, access to clinical resources, emphasis on science and discovery, and bureaucratic challenges (table 2).

Table 2.

Total Number of Times and Numbers of Respondents Referring to the Major Themes Related to the Perceptions of Clinical Care in Academic Medical Centers, From Interviews With 24 Clinically Excellent Faculty Physicians at 8 Academic Institutionsa

Competing Obligations

The theme elaborated on by the greatest number of informants was the idea that academia's tripartite mission (research, education, and patient care) can result in a diffusion of focus and energy among clinically oriented academic faculty. Some informants described real challenges with their attempts to remain clinically excellent because of the competing professional obligations and the desire to also excel as an educator and/or a researcher. Clinical faculty thought the notion of being exclusively committed to caring for patients, as is the case in most private settings, was congruent with aspirations of clinical excellence in nonacademic settings.

This was eloquently described by a cardiologist who explained:

The difficult thing about clinical excellence in academia is you have to manage all the other aspects of your academic life and still perform at a pretty high level clinically whereas people that are not so active clinically can just show up at a clinic a day a week and that's their clinic commitment. If you want to be really good clinically, you have to be able to see urgent consults; you have to be available for urgent questions and procedures. In the community, that's what you do all the time and you don't have all these other constraints.

A gastroenterologist commented on the some of the nonclinical roles and expectations that may be different between academic and nonacademic clinicians:

I think that they care for their patients and I think we care for our patients too, the difference between the 2 of us lies in areas where the private person spends hours and hours balancing the books and documenting things for insurance companies. We do somewhat less of it, we have to provide proof of scholarly work in order to be promoted and everything else.

Another interviewee emphasized the multiple hats worn in academic centers:

I think a major difference is the connection of clinical excellence to teaching and research… Not only the opportunity but really the obligation to interact and to share and learn from other people.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Many of the physician informants highlighted the “public” nature to the practice of clinical medicine in academia, mentioning that it often involved an interdisciplinary team, was observed by learners, and not infrequently was formally and informally shared with colleagues. They opined that cooperation around cases added value to the care delivered to patients. Discussion about cases and sharing with colleagues and learners was thought to be indispensable.

A clinician who also spends 25% of his time teaching described the intersection between teaching and clinical care in the academic setting:

…the presence of learners and people constantly observing your interactions and diagnostic thought process and learning from that is far more prevalent in the academic setting than it would be in the private or primary practice setting…whereas, in a practice setting…the main people that are learning from you are the patients, and to some extent, your support staff…

A rheumatology professor described how clinicians in academia need to refine their skills related to coordinating a team within a large and complex system:

In academics, your clinical excellence has to be, in part, measured by the interactions that you have with the house staff and the patients that are being seen by a team. There has to be a skill set having to deal with heading up a diagnostic and therapeutic team, not just a single one-on-one communication.

Another clinician who spends 60% of his time in clinical care described how the team nature of care in academics not only benefited the learners, but also supported the attending physician:

I think the way I work in academia is as part of a team, and taking care of patients also involves a learning experience for me and the people I'm working with. I think if I were in practice, I think it would be quite different. I would be working alone…. So I think it's a different orientation; probably less learning as part of a team in community practice than in academia.

Types of Patients Seen and Expectations About Productivity

Interviewees believed that, in terms of severity of illness and complexity, there are differences in the types of patients cared for in academic and nonacademic settings. They also conveyed the view that differences in terms of productivity expectations influence how clinical excellence may be distinctly realized in these settings.

One participant provided a description of how he thought patients were different in the 2 settings:

Patients are more complex, they have multiple organ system abnormalities, more immune-suppression, more interaction of different disease processes—that tends to happen more in the academic setting than in the practice setting. So I think the differential diagnosis is different. I think you wrestle with uncertainty a little bit more in the academic setting when you are deciding on clinical decisions.

Another clinician explained that socioeconomic and insurance disparities were a factor that influenced her preference for practicing in an academic setting:

…many times we are seeing patients who might not have access to care. To me, that is an important reason that I am in academics.

A doctor who spends 45% of his time in clinical work but who had previously worked in private practice compared the types of illnesses seen in the 2 settings:

There are differences in the patient population that you see. When I was in private practice, I saw many more acute problems that evolved for hours before I saw them. In academics, the patients that you see are much more “consultated,” meaning that they have seen other physicians. I think the diagnostic difficulties in academics are different.

Similarly, another participant who had begun her career in private practice and then became an academic pulmonologist commented:

We receive the sickest of the sick, the patients that the community pulmonologist generally won't manage and then a lot of uninsured patients. So, I think that the complexity of the University practice is laboriously more than a private practice.

An infectious disease clinician emphasized that many patients come to academic institutions later in the course of illness:

In an academic setting, I think that you have to be able to deal with complexities of patients that are not necessarily seen in the community setting, or they've been seen in the community setting and now they come here with stacks of charts. Time wise, we are allowed to spend a whole lot more time on our patients in academics than I would be allowed to if I wanted to make any money out in the community practice. So I view that as a luxury….

Resources That Support Clinical Excellence

Informants highlighted perceived differences in resources that support provision of excellent clinical care in the 2 settings. Having easy access to expert consultants was noted as being highly advantageous. Clinical trials assessing new therapeutics and state-of-the-art technology, particularly with respect to imaging, were thought to be more available to clinicians practicing in academia.

An endocrinologist who spends 50% of his time in clinical care related how the additional resources available in academic medicine made providing excellent care easier:

I think the University endocrinologist has the edge and the main reason is that endocrinology depends to a really great extent on support services like the department of radiology, nuclear medicine, endocrine surgery, laboratories. One advantage of an academic endocrinologist is that the individual is working closely with these various departments, whereas I think the community endocrinologist is more isolated in a community practice, not rubbing shoulders on a daily basis with people in the other support areas which are critical to the practice of endocrinology.

A cardiologist who spends 55% of his time in providing clinical care described the culture supporting safety at AMCs that may be different from many private settings:

If there is really a difficult problem in any kind of regard, I think that if you have very bright people around, that not only share the good results but can help keep you from doing stupid things.

Emphasis on Science and Discovery

As AMCs continue to emphasize the tripartite mission of teaching, discovery, and clinical care, several academic physicians described how their practices were influenced by the emphasis on research.

One physician described that the clinical thought process in academia more overtly drives clinical research questions. One oncologist at the associate professor level stated:

An academic clinician, I think, needs to go a step further and not just know guidelines, but know what's on the horizon, know the directions.

A professor of hematology thought that clinical excellence in academia is constantly challenging the way things are done in an effort to improve:

I think in an academic model you have to still maintain an academic interest which I would define as not just wanting a status quo, but wanting to always get better and also having that interest of developing better practices or better systems of researching what you're doing.

Bureaucracy and Politics That Interfere With Clinical Excellence

Informants described significant bureaucratic and political challenges that hindered the provision of excellent clinical care in the academic setting. This idea is summarized by a professor who is 50% clinically active:

If I had to compare a large academic medical center such as this, maybe with a smaller community hospital, I would probably say it's tougher in a large medical center because everything is so big…. To get one's concerns heard may be a little more difficult. I think it's just a reflection of size more than anything else…. It just takes a lot of time, whereas if you were in a private office, you can hire and fire.

A cardiologist expressed frustrations with the bureaucracy in academics:

We are in a very, very big place where we have no control over things that patients are concerned about—traffic flow, lack of parking, who their bed mate's going to be in the next room or the next bed…. We get this all the time, “We love you as a doctor but we don't want ever come to your hospital again.”

Discussion

In this qualitative study, 6 major themes emerged regarding clinical care in the academic setting according to faculty identified by their department chairs as being clinically excellent. Excellent clinicians described eloquently the features of providing clinical care in the academic setting, including facilitators (eg, more human and technical resources), challenges (eg, competing demands on time), and differences from care in the private sector (eg, need to collaborate with an interdisciplinary team). These perceptions may be useful in understanding why physicians choose to practice in AMCs and how to better support those who do; they also may provide important inferences for how to manage the culture in AMCs to improve the quality medical care and the careers of clinicians striving to deliver that care. According to academic clinicians, physicians who tend to enjoy practicing medicine in a more “public” fashion may enjoy the perceived enhanced teamwork and collaboration found in academic settings, but will also need a different skill set to work effectively in the presence of learners and to manage larger care teams.

Likewise, the responses to our study imply that clinicians who prefer to have the “first crack” at making a diagnosis may not enjoy the academic setting as much as a nonacademic venue because these clinicians believed that patients in academic settings often may have had diagnostic evaluations before the patient came to the AMC. Notably, three-fourths of the respondents were subspecialists in this study, and whether primary care physicians in academics would agree with this belief is unknown from our analysis. The culture of challenging the status quo in academics may be perceived as exciting or frustrating, depending on one's fondness for change. Understanding the perceived barriers and facilitators to providing excellent clinical care in the academic setting may have implications for academia's ability to recruit and retain clinician role models and may prove useful in planning strategies and systems to promote high-quality care in the academic setting.

Understanding the perceptions of clinical faculty likely is useful in supporting the mental and physical health of academic faculty members. In a recent review of a book on this topic, the author of the review asserted, “If one accepts the book's assumption that being a faculty member introduces additional pressures and responsibilities above and beyond those of a physician, the lack of research evidence specific to faculty members is a serious deficiency.”21 Our study begins to address the gap in knowledge about such pressures.

Our study has several limitations. First, it relied exclusively on self-report. However, this is considered to be the most direct approach for understanding attitudes and beliefs. Second, our qualitative study is limited to clinically excellent physicians in departments of medicine at 8 AMCs, and as such our findings may not apply to other institutions, departments, or to clinical excellence in the private sector. Two physicians spontaneously commented that they had experience working in a nonacademic setting for some time during their careers, but the majority did not have this firsthand perspective. Third, 2 physicians declined participation and it is possible that their perspectives may have been different. Fourth, the data were analyzed by 2 academic physicians who value clinical excellence in academia, so bias could have been introduced in extraction of themes; however, interviews were transcribed verbatim to minimize this possibility. Finally, it is important to note that the responses to the open-ended questions emerged spontaneously. Qualitative analysis does not allow us to know whether “teamwork and collaboration” was a more important theme than “emphasis on discovery” merely because it was mentioned more frequently. If all subjects were specifically asked about each theme, the number of comments related to each would certainly be much higher.

This study describes how clinically excellent academic physicians perceive their roles, obligations, rewards, and limitations to providing clinical care in the academic settings, with several important themes emerging. It is likely that the perceptions of clinically excellent academicians are highly influential to learners exposed to them and could influence career decisions of those learners interested in clinical care. These opinions may also be informing regarding the culture surrounding clinical care in AMCs and, as perceptions, may or may not be factually accurate. As perceptions, these findings are provocative and deserve further investigation.

Footnotes

All authors are at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Colleen Christmas, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Divisions of Geriatrics; Samuel C. Durso, MD, MBA, is Mason F. Lord Professor of Medicine, Divisions of Geriatrics; Steven J. Kravet, MD, MBA, is President of Johns Hopkins Community Physicians and Assistant Professor of Medicine, General Internal Medicine; and Scott M. Wright, MD, is Arnold P. Gold Foundation Associate Professor of Medicine, General Internal Medicine.

All authors are Miller-Coulson Family Scholars and this work is supported by the Miller-Coulson family through the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine.

References

- 1.Bendapudi N. M., Berry L. L., Frey K. A., Parish J. T., Rayburn W. L. Patients' perspectives on ideal physician behaviors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):338–344. doi: 10.4065/81.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arora R., Singer J., Arora A. Influence of key variables on the patients' choice of a physician. Qual Manag Health Care. 2004;13(3):166–173. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Junod Perron N., Favrat B., Vannotti M. Patients who attend a private practice vs a university outpatient clinic: how do they differ? Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134(49–50):730–737. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harewood G. C., Lieberman D. A. Prevalence of advanced neoplasia at screening colonoscopy in men in private practice versus academic and Veterans Affairs medical centers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(10):2312–2316. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckley L. M., Sanders K., Shih M., Hampton C. L. Attitudes of clinical faculty about career progress, career success and recognition, and commitment to academic medicine: results of a survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2625–2629. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S. W. The decline of academic medicine. Lancet. 2006;368(9532):284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levinson W., Rubenstein A. Mission critical—integrating clinician-educators into academic medical centers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(11):840–843. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909093411111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levinson W., Branch W. T., Jr, Kroenke K. Clinician-educators in academic medical centers: a two-part challenge. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(1):59–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-1-199807010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey R. M., Wheby M. S., Reynolds R. E. Evaluating faculty clinical excellence in the academic health sciences center. Acad Med. 1993;68(11):813–817. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones R. F., Gold J. S. Faculty appointment and tenure policies in medical schools: a 1997 status report. Acad Med. 1998;73(2):212–219. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199802000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beasley B. W., Simon S. D., Wright S. M. A time to be promoted: the Prospective Study of Promotion in Academia (Prospective Study of Promotion in Academia) [published online ahead of print December 7, 2005] J Gen Intern Med. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wright S. What do residents look for in their role models? Acad Med. 1996;71(3):290–292. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199603000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright S., Wong A., Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):53–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.12109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder S. A., Zones J. S., Showstack J. A. Academic medicine as a public trust. JAMA. 1989;262(6):803–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.America's best graduate schools, 2006. U.S. News & World Report. Available at: http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools. Accessed July 21, 2010.

- 16.Crabtree B. F., Miller W. L. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schonberg M. A., Ramanan R. A., McCarthy E. P., Marcantonio E. R. Decision making and counseling around mammography screening for women aged 80 or older. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):979–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green M. L., Ruff T. R. Why do residents fail to answer their clinical questions? A qualitative study of barriers to practicing evidence-based medicine. Acad Med. 2005;80(2):176–182. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200502000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratanawongsa N., Teherani A., Hauer K. E. Third-year medical students' experiences with dying patients during the internal medicine clerkship: a qualitative study of the informal curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):641–647. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright S. M., Carrese J. A. Excellence in role modeling: insight and perspectives from the pros. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):638–643. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruppen L. D. reviewer. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1343–1344. Review of: Cole TR, Goodrick TJ, Gritz ER, eds. Faculty Health in Academic Medicine: Physicians, Scientists, and the Pressures of Success. [Google Scholar]