Abstract

Objectives:

The aims of this study were to investigate the predictive value of an elevated level of alanine transaminase (ALT) for biliary acute pancreatitis (AP) and to reconsider the role of abdominal ultrasound (AUS).

Methods:

All patients admitted to Christchurch Public Hospital with AP between July 2005 and December 2008 were identified from a prospectively collected database. Peak ALT within 48 h of presentation was recorded. Aetiology was determined on the basis of history, AUS and other relevant investigations.

Results:

A total of 543 patients met the inclusion criteria. Patients with biliary AP had significantly higher median (range) ALT than those with non-biliary causes (200 units/l [63–421 units/l] vs. 33 units/l [18–84 units/l]; P < 0.001). An ALT level of >300 units/l had a sensitivity of 36%, specificity of 94%, positive predictive value of 87% and positive likelihood ratio of 5.6 for gallstones. An elevated ALT and negative AUS had a probability of 21–80% for gallstones.

Conclusions:

An elevated ALT strongly supports a diagnosis of gallstones in AP. Abdominal ultrasound effectively confirms this diagnosis; however, a negative ultrasound in the presence of a raised ALT does not exclude gallstones. In some patients consideration could be given to proceeding to laparoscopic cholecystectomy based on ALT alone.

Keywords: alanine transaminase, cholecystectomy, pancreatitis

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common surgical presentation. Gallstones and excessive alcohol consumption are the most frequent causes of AP and together account for approximately 80% of underlying aetiology.1 Up to 60% of all presentations of AP are secondary to gallstones.2 Other aetiologies are diverse and include pancreatic divisum, malignancy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), hypercalcaemia, drug use and infection.3

The pathophysiology of biliary AP (BAP) remains unclear; however, common theories of causes include: increased ductal pressure secondary to a stone lodged in the ampulla of Vater leading to autodigestion by pancreatic enzymes; reflux of bile into the pancreas, and sphincter of Oddi incompetence and reflux of duodenal contents into the pancreatic duct with subsequent damage to the pancreatic parenchyma.4

The clinical severity of AP ranges from mild to severe, with an overall mortality of about 10%.4 It is important that biliary pancreatitis is promptly diagnosed, as specific interventions such as endoscopic sphincterotomy and cholecystectomy can avoid complicated and recurrent disease.5

The standard first-line investigation in centres with or without endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) facilities to determine a biliary aetiology in AP is abdominal ultrasound (AUS). In uncomplicated cholecystolithiasis, AUS has a sensitivity for gallstones of 92–98%.6,7 However, in the presence of pancreatitis with associated ileus and bowel distension, the sensitivity for cholecystolithiasis drops to 67–87%.2 The sensitivity of AUS for choledocholithiasis has been reported to be as low as 20–50%.2 It has been proposed that alanine transaminase (ALT) may be a more useful predictor of gallstones in AP than AUS.8 Although EUS is more sensitive and specific for gallstones and microlithiasis in AP than AUS,7 this investigation is not widely available in New Zealand. In fact, at the time of writing there was only one unit in the whole country.

Several biochemical investigations have been proposed to identify a biliary aetiology, including bilirubin, ALT, alkaline phosphatase and aspartate transaminase. An elevated ALT is widely considered the most useful of these markers. A 1994 meta-analysis found that an ALT level of >150 units/l had a positive predictive value (PPV) for gallstone pancreatitis of 95%.9 Other studies using variable thresholds for ALT identified PPVs of 78.8–100%.8,10,11 A prospective study of 269 patients with BAP found that 12.3% had a normal ALT and 16.7% had an elevation of less than three times the upper limit of normal.12

Thus, the aims of this study were to determine the predictive value of a raised ALT in determining a biliary aetiology in patients presenting with AP and, in particular, by focusing on the pre- and post-test probability of a biliary aetiology following AUS, to clarify the usefulness of AUS in clinical decision making in patients presenting with AP.

Materials and methods

Patients admitted with their first presentation of pancreatitis between July 2005 and December 2008 were identified from a prospectively collected database. Data retrieved included demographics, predicted severity using Apache (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation) II scores, investigations performed, surgical treatment and aetiology. Data on peak ALT during the first 48 h after admission were sourced from the hospital's electronic clinical information system.

The diagnosis of gallstones was made by AUS, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Acute pancreatitis secondary to alcohol consumption was diagnosed in patients who reported drinking >40 units of alcohol per week and in whom gallstones were excluded on AUS.

The centre at which this study was performed does not have access to EUS and therefore AUS has been the primary imaging modality used to investigate postulated biliary pancreatitis.

The database had previously met the definition of an audit and quality assurance tool as per New Zealand national ethics committee guidelines and therefore its use did not require specific ethical committee review.13

Statistics and analysis

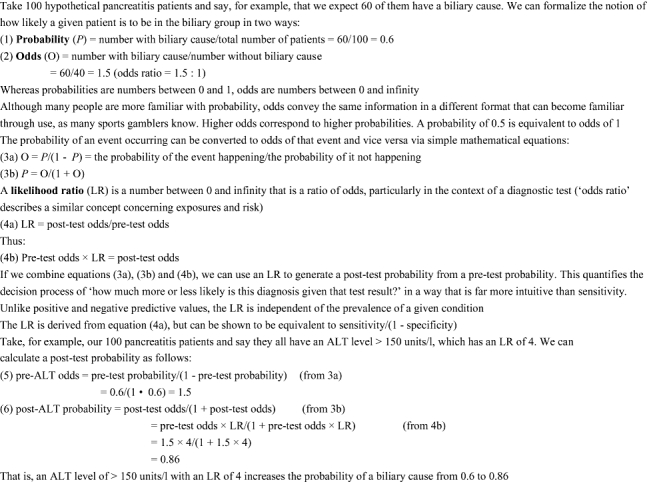

The group of patients with BAP was compared with a combined group of patients with AP of non-biliary causes. Continuous variables are presented as median and range; categorical variables are shown as a percentage of the total study population. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous variables. The chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Multivariate analysis was carried out using logistic regression. The prevalence of gallstones within the study population was used as the pre-ALT probability of gallstones. Likelihood ratios (LRs) for ALT predicting gallstones in AP at various thresholds were calculated and used to generate post-ALT probabilities for specific subgroups. Likelihood ratios for BAP based on positive and negative AUS were derived from a recent review study, listing sensitivity of 67–87%, specificity of 93%, PPV of 100% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 75%.2 This review paper provided similar data to those seen in earlier review articles, which listed sensitivity as 62–95%.14,15 The post-AUS probability of a biliary cause for AP was calculated using the post-ALT probability of BAP at various ALT thresholds as the pre-AUS probability. To calculate the post-test probability using the LR, the pre-test probability (expressed as a value between 0 and 1) was converted into odds (pre-test probability/[1 – pre-test probability]) and multiplied by the LR to calculate the post-test odds. This was then converted to the post-test probability (post-test odds/[1 + post-test odds]). A working example and an explanation of these calculations are given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

An example of probability, odds and likelihood ratio. ALT, alanine transaminase

Results

A total of 609 patients were identified on the database for the period of July 2005 to December 2008. Sixty patient admissions were excluded as they represented recurrent presentations to hospital with AP; five were excluded because an ALT was not performed, and one was excluded as the national hospital index number was stored inaccurately on the database. This left a total of 543 patients for analysis. Demographics and investigations are shown in Table 1. The use of MRI is not shown as it was not specifically recorded in the database. The relative frequencies of the various aetiologies are shown in Table 2. Univariate analyses comparing biliary vs. non-biliary aetiologies are shown in Table 3. Logistic regression identified age (P < 0.001), ALT (P < 0.001) and gender (P= 0.0412) as independent predictors of a biliary cause in AP.

Table 1.

Demographics of and investigations performed in the study population (n= 543)

| Demographics and investigations | |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 57 (40–72) |

| Female, n (%) | 283 (52) |

| Abdominal ultrasound, n (%) | 448 (84) |

| Computed tomography, n (%) | 156 (29) |

Table 2.

Aetiology of acute pancreatitis in patients presenting with first episodes of acute pancreatitis at Christchurch Hospital between July 2005 and December 2008 (n= 543)

| Aetiology | Patients, n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gallstones | 292 | 53.8 |

| Unknown | 131 | 24.1 |

| Alcohol | 53 | 9.8 |

| Other | 39 | 7.2 |

| ERCP | 14 | 2.6 |

| SOD | 7 | 1.3 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 3 | 0.6 |

| Pancreatic divisum | 2 | 0.4 |

| Trauma | 2 | 0.4 |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; SOD, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

Table 3.

Demographics, alanine transaminase (ALT), predicted severity and outcome in patients with biliary and non-biliary acute pancreatitis (BAP)

| BAP | Non-BAP | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 292 (54) | 251 (46) | |

| Median age, years (range) | 63 (44–75) | 51 (34–68) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 168 (58) | 115 (46) | 0.006 |

| Median ALT, units/l (range) | 200 (63–421) | 33 (18–84) | <0.001 |

| Median Apache II score, (range) | 6 (3–9) | 5 (2–7) | <0.001 |

| Median C-reactive protein, mg/l (range) | 104 (18–222) | 82 (11–223) | 0.413 |

| C-reactive protein > 150 mg/l, n (%) | 118 (40) | 91 (36) | 0.269 |

| Any necrosis on CT, n (%) | 27 (9.3) | 16 (6.4) | 0.217 |

| CT necrosis < 30%, n (%) | 16 (5.5) | 7 (2.8) | 0.121 |

| CT necrosis > 30%, n (%) | 11 (3.8) | 9 (3.6) | 0.911 |

| Death prior to discharge, n (%) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (1.1) | 0.996 |

CT, computed tomography

Table 4 demonstrates the diagnostic value of age, gender and ALT at different thresholds using sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and LRs. Table 5 uses the pre-ALT test probabilities for the study population and relevant subgroups, and the LRs generated at different ALT thresholds, to determine the post-ALT test probability of gallstones in AP. Table 6 demonstrates the probability of a biliary cause for AP at various ALT thresholds in the presence of a positive or negative AUS, based on the sensitivity and specificity of AUS in a review paper.2

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood ratio (LR) for gender, age and alanine transaminase (ALT) in biliary acute pancreatitis

| Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % | Positive LR | Negative LR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 58 | 54 | 59 | 52 | 1.26 | 0.78 |

| Male | 42 | 46 | 48 | 41 | 0.78 | 1.26 |

| Age > 50 years | 67 | 49 | 60 | 56 | 1.31 | 0.67 |

| Age > 60 years | 54 | 67 | 66 | 56 | 1.64 | 0.69 |

| ALT < 30 units/l | 14 | 53 | 25 | 35 | 0.29 | 1.64 |

| ALT > 100 units/l | 66 | 79 | 79 | 67 | 3.20 | 0.43 |

| ALT > 150 units/l | 59 | 84 | 81 | 64 | 3.70 | 0.49 |

| ALT > 300 units/l | 36 | 94 | 87 | 56 | 5.66 | 0.68 |

| ALT > 500 units/l | 20 | 98 | 92 | 51 | 9.84 | 0.82 |

Table 5.

Post-alanine transaminase (ALT) probability of biliary cause for acute pancreatitis based on ALT in the total population and in subgroups

| Population probability. % |

Subgroup probability, % |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Age > 50 years | Age > 60 years | Female > 50 years | Female > 60 years | |||

| Pre-test | 54 | 59 | 48 | 60 | 66 | 63 | 66 | |

| Probability | ||||||||

| ALT, units/l | Positive likelihood ratio | |||||||

| <30 | 0.29 | 25 | 29 | 21 | 30 | 36 | 33 | 36 |

| >50 | 2.3 | 72 | 76 | 68 | 77 | 81 | 79 | 82 |

| >100 | 3.2 | 79 | 82 | 75 | 83 | 86 | 84 | 86 |

| >150 | 3.7 | 81 | 84 | 77 | 85 | 88 | 86 | 88 |

| >200 | 4.3 | 83 | 86 | 80 | 87 | 89 | 88 | 89 |

| >300 | 5.6 | 87 | 89 | 84 | 89 | 92 | 91 | 92 |

| >400 | 7.5 | 90 | 91 | 87 | 92 | 94 | 93 | 94 |

| >500 | 9.8 | 92 | 93 | 90 | 94 | 95 | 94 | 95 |

Table 6.

Post-abdominal ultrasound (AUS) probability of biliary cause for acute pancreatitis at various alanine transaminase (ALT) thresholds, based on likelihood ratios for AUS derived from the literature (2)

| ALT, units/l | Population pre-AUS probability, % | Post-positive AUS probability, % | Post-negative AUS probability, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 25 | 76–80 | 4–10 |

| >30 | 65 | 95–96 | 21–40 |

| >50 | 72 | 96–97 | 26–47 |

| >100 | 79 | 97–98 | 34–57 |

| >150 | 81 | 98 | 37–60 |

| >200 | 83 | 98 | 41–63 |

| >250 | 87 | 98–99 | 48–70 |

| >300 | 87 | 98–99 | 48–70 |

| >350 | 89 | 99 | 53–74 |

| >400 | 90 | 99 | 56–76 |

| >450 | 92 | 99 | 62–80 |

| >500 | 92 | 99 | 62–80 |

Discussion

The current study has demonstrated that a raised ALT within 48 h of presentation to hospital is strongly predictive of a biliary origin in AP. The higher the ALT, the more likely a biliary cause becomes. This finding is supported by a number of previous studies which found that the predictive value of ALT is even greater than that demonstrated by this study. In the present cohort of patients, an ALT of >150 units/l had a PPV for gallstones of 81%, compared with a 1994 meta-analysis which found a PPV of 95% for the same ALT level.9 More recent studies have found that ALT levels that are three times the normal level or >150 units/l have PPVs for gallstones of 92–93%.16,17 Another study found that an ALT of >60 units/l had a PPV for gallstones in AP of 78.8%.18 Other studies have not presented data for higher ALT thresholds.

Consistent with previous studies,16,17 female gender (P= 0.0417) and increasing age (P < 0.0001) were shown to be independent risk factors for gallstones in AP. Thus, combining these factors with ALT results in a modest increase in the predictive power for gallstones in AP (Table 5).

The positive and negative predictive values of a test are related not only to its sensitivity (NPV) and specificity (PPV), but also to the incidence or prevalence of a condition within the population. Thus, in a population in which the incidence of a biliary aetiology is 54% and the pre-AUS test probability of gallstones in those with an elevated ALT is 65–92% (Table 6), the post-AUS test probability approaches 100% for patients with a positive AUS, but patients with a negative AUS still have a 21–80% probability of their underlying aetiology being biliary (Table 6). Thus, one could argue that cholecystectomy be considered in all patients with an elevated ALT.

Although AUS carries no risk and is inexpensive and readily available, it risks the possibility that a negative result will be interpreted as a reason not to perform cholecystectomy, although 21–80% of these patients will have a biliary aetiology depending on the level of ALT. This risk is further underlined by data indicating that untreated BAP has been associated with recurrent attacks in 13% of patients within 1 month of hospital discharge and in 17% at a median of 18 weeks after the initial episode.19,20 In addition, recurrent admissions for BAP tend to increase in length and are associated with greater morbidity.20,21 Thus, omitting cholecystectomy in the presence of occult biliary disease can be associated with significant morbidity, whereas early intervention with laparoscopic cholecystectomy is safe and effectively reduces recurrence rates.22

If cholecystectomy is not performed in patients with a high ALT and negative AUS, a number of invasive, expensive and resource-limited investigations are required, all of which can lead to significant delays in definitive treatment. Yet, a significant proportion of these patients will subsequently be found to have a biliary cause and hence require cholecystectomy. A formal cost-effectiveness analysis would be particularly useful to determine the most appropriate approach.

It is probable that this current study significantly under-diagnoses the incidence of gallstones in AP. Firstly, routine access to EUS is not possible. Several studies have shown that EUS has a greater sensitivity and specificity for BAP than AUS and reduces the number of patients diagnosed with idiopathic disease. In the current study, 24% of patients were of unknown aetiology, compared with 7–11% in studies using EUS. One of these studies found that EUS diagnosed cholecystolithiasis or choledocholithiasis in 15% of patients with a negative AUS and CT.2,10,16,17 It was difficult to assess the predictive value of AUS in the current study as the investigation represents part of the reference standard such that the result of the AUS influences the final diagnosis and decision for further investigations. The second reason for an underestimation of the true prevalence of biliary pancreatitis is that a negative initial AUS may have falsely reassured the investigating clinician and the patient may not have been followed up with further investigations. Although magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has been shown to have similar accuracy to ERCP in diagnosing BAP,23,24 this investigation is not employed routinely in patients with a negative AUS and resolving AP because of its limited availability. An underestimation of the true prevalence of BAP may explain why the PPV for ALT produced in this study is lower than that reported in other similar papers. If a number of the patients with a raised ALT were misdiagnosed as having non-biliary aetiology, the sensitivity and PPV of the test would be underestimated.

In addition, ALT within the normal range reduces the likelihood of gallstones in AP to 25%. The results of a recent review article indicate that the LR for BAP associated with a negative AUS is 0.14–0.35.2 Applying this to the current study population, a normal ALT combined with a negative AUS reduces the likelihood of gallstones to 4–10% (Table 6). Using the combination of these two factors in the clinical setting would therefore reduce the need for unnecessary cholecystectomy, thus reducing surgical workloads and hospital waiting lists, as well as enabling a more rapid investigation into alternative causes for the presenting pancreatitis.

It would have been useful to exclude patients with a history of excessive alcohol consumption in order to increase the predictive power of ALT for gallstones by increasing the pre-test probability. However, this was not possible from the data available, which did not separate a history of alcohol misuse from the final diagnosis, which was based on history and appropriate investigations to exclude other causes.

The study cohort includes all first episodes of AP presenting to Christchurch Public Hospital between July 2005 and December 2008 and therefore accurately reflects the characteristics of the local population. The study data and results may be generalized to other communities with similar genetic and lifestyle risks for pancreatitis and with comparable hospital facilities (Western world diet and genetics, low incidence of ethanol [EtOH]-induced pancreatitis, and a resource-limited, state-funded hospital system).

In conclusion, this large prospective study confirmed that ALT is a useful marker for predicting gallstones in AP and that there is a positive correlation between increasing ALT and likelihood of BAP. Older age and female gender are also independent risk factors for gallstones in AP. Abdominal ultrasound is highly specific, but has poor sensitivity for BAP and so is limited in its ability to completely exclude this diagnosis. Thus, for patients in whom ALT is elevated, proceeding to cholecystectomy without further investigation should be considered. In addition, a combination of positive AUS and elevated ALT gives an almost 100% confirmatory diagnosis of BAP.

References

- 1.Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG. Aetiology and pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis: current concepts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:343–356. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexakis N, Lombard M, Raraty M, Ghaneh P, Smart HL, Gilmore I, et al. When is pancreatitis considered to be of biliary origin and what are the implications for management? Pancreatology. 2007;7:131–141. doi: 10.1159/000104238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang GJ, Gao CF, Wei D, Wang C, Ding SQ. Acute pancreatitis: aetiology and common pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1427–1430. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West D, Adrales GL, Schwartz RW. Current diagnosis and management of gallstone pancreatitis. Cur Surg. 2002;59:296–298. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7944(01)00615-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayub KSJ, Imada R, Slavin J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD003630. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003630.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooperberg PL, Burhenne HZ. Real-time ultrasonography. Diagnostic technique of choice in calculous gallbladder disease. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1277–1279. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198006053022303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chak A, Hawes RH, Cooper G, Hoffman B, Catalano M, Herbener T, et al. Prospective assessment of the utility of EUS in the evaluation of gallstone pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:599–604. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ammori B, Boreham B, Lewis P, Roberts S. The biochemical detection of biliary aetiology of acute pancreatitis on admission: a revisit in the modern era of biliary imaging. Pancreas. 2003;26:32–35. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenner S, Dubner H, Steinberg W. Predicting gallstone pancreatitis with laboratory parameters: a meta-analysis. Am Coll Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1863–1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson B, Neoptolemas JP, Leese T, Carrlocke D. Biochemical prediction of gallstones in acute pancreatitis: a prospective study of three systems. Br J Surg. 1988;75:213–215. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazmierczak S, Catrou PG, Van Lente F. Enzymatic markers of gallstone-induced pancreatitis identified by ROC curve analysis, discriminant analysis, logistic regression, likelihood ratios, and information theory. Clin Chem. 1995;41:523–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dholakia K, Pitchumoni CS, Agarwal N. How often are liver function tests normal in acute biliary pancreatitis? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:81–83. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health National Ethics Advisory Committee. Ethical guidelines for observational studies: observational research, audits and related activities. c2006 [updated 11 June 2008; cited 24 June 2008]. http://www.newhealth.govt.nz/neac/

- 14.Larson SD, Nealon W, Evers BM. Management of gallstone pancreatitis. Adv Surg. 2006;40:265–284. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner MA. The role of US and CT in pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(Suppl):241–245. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, Fan ST, Lo C, Tso W, Wong Y, Poon R, et al. Clinico-biochemical prediction of biliary cause of acute pancreatitis in the era of endoscopic ultrasonography. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:423–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy P, Boruchowicz A, Hastier P, Pariente A, Thevenot T, Frossard J, et al. Diagnostic criteria in predicting a biliary origin of acute pancreatitis in the era of endoscopic ultrasound: multicentre prospective evaluation of 213 patients. Pancreatology. 2005;5:450–456. doi: 10.1159/000086547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neoptolemos J, Hall AW, Finlay D, Berry J, Carr-Locke D, Fossard D. The urgent diagnosis of gallstones in acute pancreatitis: a prospective study of three methods. Br J Surg. 1984;71:230–233. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez V, Pascual L, Almela P, Anan R, Herreros B, Sanchiz V, et al. Recurrence of acute gallstone pancreatitis and relationship with cholecystectomy or endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;99:2417–2423. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito K, Hiromichi I, Whang E. Timing of cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis: do the data support current guidelines? J Gastrointest Surg. 12:2164–2170. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0603-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alimoglu O, Ozkan OV, Sahin M, Akcakaya A, Bas G. Timing of cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis: outcomes of cholecystectomy on first admission and after recurrent biliary pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2003;27:256–259. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uhl W, Muller CA, Krähenbühl L, Schmid S, Scholzel S, Buchler M. Acute gallstone pancreatitis: timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild and severe disease. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1070–1076. doi: 10.1007/s004649901175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aube C, Delorme B, Yzet T, Burtin P, Lebigot J, Pessaux P, et al. MR cholangiopancreatography versus endoscopic sonography in suspected common bile duct lithiasis: a prospective, comparative study. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:55–62. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ainsworth A, Rafaelsen SR, Wamberg P, Durup J, Pless T, Mortensen M. Is there a difference in diagnostic accuracy and clinical impact between endoscopic ultrasonography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography? Endoscopy. 2003;35:1029–1032. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]