Abstract

Background

A significant body of research on minority health shows that while Hispanic immigrants experience unexpectedly favorable outcomes in maternal and infant health, their advantage deteriorates with increased time of residence in the US. This is referred to as the “acculturation paradox.”

Objective

We assess the “acculturation paradox” hypothesis that attributes this deterioration in birth and child health outcomes to negative effects of acculturation and behavioral adjustments made by immigrants while living in the US, and investigate the potential for the existence of a selective return migration.

Design

We use a sample of Mexican immigrant women living in two Midwestern communities in the US to analyze the effects of immigrant duration and acculturation on birth outcomes once controlling for social, behavioral, and environmental determinants of health status. These results are verified by conducting a similar analysis with a nationally representative sample of Mexican immigrants.

Results

We find duration of residence to have a significant and nonlinear relationship with birth outcomes and acculturation to not be statistically significant. The effect of mediators is minimal.

Conclusion

The analyses of birth outcomes of Mexican immigrant women shows little evidence of an acculturation effect and indirectly suggest the existence of a selective return migration mechanism.

Keywords: Hispanics, Latinos, Mexican immigrants, acculturation, maternal and infant health, birth outcomes, return migration, selection

Introduction

A significant body of research on minority health in the United States shows that Hispanics (hereto after the terms Hispanic and Latino are used interchangeably) experience an advantage in maternal and infant health outcomes (referred to as the “Hispanic paradox”). Indeed, birth outcomes of infants born to Hispanic immigrants are nearly equal to, or better than, birth outcomes of infants born to US-born White women (Markides and Coreil, 1986, Becerra et al., 1991, Albrecht et al., 1996, Franzini et al., 2001, de la Rosa, 2002). However, this health advantage has been found to deteriorate with each subsequent generation (Scribner and Dwyer, 1989, Guendelman et al., 1990, de la Rosa, 2002, Collins and David, 2004, Collins et al., 2006, Ruiz et al., 2006, Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2007). Most studies attribute this decline in health to the negative effects of acculturation (Scribner and Dwyer, 1989, Guendelman et al., 1990, de la Rosa, 2002), that is, the changes in tastes, preferences, and behaviors experienced by immigrants as they adapt to living in the host country. Because this finding is inconsistent with the national narrative that immigrants and subsequent generations should experience an improvement in their lives, this is referred to here as the “acculturation paradox.”

While the health advantage among Hispanics has been widely investigated, albeit not yet fully understood, research on the deterioration of Hispanic health with increased length of residence remains poorly studied and even less understood. This study fills the gap in the research on intragenerational change in Latino Health by examining the association between length of residence in the U.S. and birth outcomes of first generation Mexican immigrant women. Furthermore, whereas a few studies that have examined the change in birth outcomes within the first generation (Guendelman and English, 1995, Zambrana et al., 1997, Balcazar and Krull, 1999), a weakness has been that duration of stay and acculturation is often conflated, assuming that the former is a good indicator of the latter. The complexity of this relationship has been demonstrated by studies showing seemingly contrary results, better birth outcomes among both the least acculturated and longest residents, and among the Mexican-born and English-speaking (Balcazar and Krull 1999; English, Kharrazi, and Guendelman 1997). We accept this complexity and suggest that separate estimation of duration and acculturation effects might uncover the operation of different processes among the healthiest immigrant mothers, such as a selective return migration.

Our study investigates the effects of length of residence in the US and acculturation on birth outcomes of first generation Mexican immigrant women separately and jointly to establish those mediating mechanisms. Our objective is to assess the acculturation paradox hypothesis: that which attributes this deterioration to the negative effects of acculturation and the associated behavioral shifts made by immigrants while living in the US. In addition, this observed deterioration may also result from a process of selective return migration, whereby immigrant mothers in better health return to their home countries at higher rates than those who experience worse health. While we are unable to properly test for selective return migration in this analysis, we do investigate the potential for its existence. Thus the strength of our approach is that we are able to focus more closely on the process of acculturation and duration over a single generation to at least indirectly investigate selective return migration.

For this study, we first analyze the strength of the effects of duration and acculturation on birth outcomes using a sample of Mexican immigrant women living in two Midwestern communities in the US. This is done by controlling for several behavioral, social, and environmental factors and then examining the resulting effects on duration and acculturation. We then verify that our results are generalizable to the Mexican immigrant population more broadly by conducting a similar analysis using a national sample of this population.

Background

In the 1960s, a study by Teller and Clyburn (Teller and Clyburn, 1974) found the surprising result that the infant mortality rate among the Spanish-speaking population in Texas was only slightly higher than that of Whites. Since then, numerous studies using local, state, and national data from the US have shown that birth and health outcomes of infants (including low birth weight, prematurity, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and survival during the first year) born to Hispanics (except Puerto Ricans) in general and Mexican-origin women in particular are nearly equal to, or better than, the birth and health outcomes of infants born to US-born White women (Markides and Coreil, 1986, Becerra et al., 1991, Albrecht et al., 1996, Franzini et al., 2001, de la Rosa, 2002). This finding is commonly referred to as the Hispanic paradox because the observed high level of favorable health outcomes is unexpected, particularly when compared to other US racial and ethnic minority groups who possess a similarly low socioeconomic profile as Hispanics. There are two primary explanations for this paradox: favorable behavioral health profiles coupled with strong social support and the health selection of migration at origin and destination (Sherraden and Barrera, 1996, Palloni and Morenoff, 2001, Goldman et al., 2006, Harley and Eskenazi, 2006, Hummer et al., 2007).

Simultaneously with the Hispanic paradox it has been observed that these initial health advantages, particularly for Mexican-origin women, diminish with increased duration of residence in the US. For example, studies have found that when comparing health differences across generations, it has been found that US-born Hispanics have higher rates of infant mortality and low birth weight than non-US-born Hispanics (Scribner and Dwyer, 1989, Guendelman et al., 1990, Cobas et al., 1996, Landale et al., 1999, de la Rosa, 2002). However, according to the US public discourse and national narrative on the immigrant experience over the past century, the lives of immigrants and their descendants should improve with increased exposure to a US lifestyle (Park, 1921, Alba and Nee, 1997, Rumbaut, 1997). Given that a worsening health status among Hispanic immigrants is inconsistent with the expected immigrant experience, it is referred to here as the “acculturation paradox.” Two hypotheses that could explain this paradox—negative acculturation and selective return migration—are described below.

Negative acculturation

The acculturation hypothesis proposes that changes in behaviors and social conditions for immigrants, due to acculturation and adjustment, result in negative effects on maternal and infant health outcomes. Acculturation refers to the process by which immigrants’ tastes, preferences, and behaviors become more similar to that of the native population as they adapt to living in the host country. Studies have found that after settling in the US, changes in tastes, preferences, and health-related behaviors may have deleterious effects on the health of Hispanic immigrants (Scribner and Dwyer, 1989, Guendelman et al., 1990, Guendelman and Abrams, 1994, Guendelman and Abrams, 1995, Cobas et al., 1996, English et al., 1997). The immigrant enters the US having left contexts that supply protective social relations and promote behaviors and practices associated with favorable infant health outcomes (Kana’iaupuni et al., 2005).

As they settle into a new life, some of these traits and environments are lost and replaced by others with more dubious health benefits, such as changes in dietary habits; increased levels of smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy; and, in some cases, less access to preventative healthcare. National studies provide evidence that first generation Mexican immigrant women have healthier nutrient intake, including higher levels of protein, vitamins A and C, folic acid, and calcium than do second generation Mexican American women or White women of childbearing age, even after controlling for a number of confounders (Abrams and Guendelman, 1995, Guendelman and Abrams, 1995, Cobas et al., 1996). Research on smoking, alcohol consumption, and substance abuse finds significant differences between US-born and non-US-born Mexican-origin women. Increased smoking and alcohol consumption are correlated with acculturation and higher-order generations among Mexican-origin women (Haynes et al., 1990, Balcazar et al., 1991, Cobas et al., 1996).

Social support and exposure to stress have also been hypothesized to influence maternal and infant health (Zambrana et al., 1997, Balcazar et al., 2001, Harley and Eskenazi, 2006). In particular, this line of research argues that the erosion of traditional social support resulting from the act of migration itself and its effects, such as isolation and physical segregation, undermines one’s ability to cope with a pregnancy in a healthy manner. The experience of living in the US, frequently in low-income, high-crime, segregated communities and with language barriers or racial discrimination surely augment the already stressful experience of migration. Thus, prenatal stress is found to be greatest among Hispanics with higher levels of acculturation and integration and also associated with increased substance use and low social support (Zambrana et al., 1997).

Selection via return migration

Studies have also shown that a selection bias may produce a significant effect on immigrant health status (Jasso et al. 2004; Palloni and Ewbank 2004; Palloni and Morenoff 2001), although one study suggests otherwise (Akresh and Frank 2008). The selective return migration hypothesis proposes that the effect of acculturation is an artifact of higher rates of return migration among the healthiest mothers (and their families). That is, on average women who are in ill health or whose children experience health problems are less likely to return to their home country than others, perhaps as a consequence of needed health services either anticipated or received. In such a case, one will observe a negative gradient of health outcomes with respect to length of stay. The gradient will be sharper if the rate of return is inversely associated with acculturation and/or duration. This phenomenon produces the illusion of initially favorable health outcomes among immigrants and of a subsequent deterioration among those remaining in the US entirely that is accounted for by a health-selected return migrant stream. As a result, at longer durations the composition of the remaining immigrant population will be disproportionately represented by those with poorer health outcomes. Such a pattern is consistent with studies that show, on average, a higher level of healthcare utilization among Mexican immigrants with a longer duration in the US (LeClere et al., 1994, Durden, 2007).

Although a negative gradient of health outcomes due to selection bias is a plausible scenario, the reverse situation has been invoked more frequently in studies of adult Hispanic mortality. That is, Hispanic adults in ill health are more likely to return to Mexico because the adverse conditions they experience are insufficiently serviced in the US healthcare system (Abraido-Lanza et al., 1999, Palloni and Arias, 2004). However, if this scenario dominates among childbearing-aged Hispanic women, one would expect to find better health outcomes among those who remain in the US for longer durations, not worse as predicted by the selective return migration hypothesis for maternal health. Furthermore, a recent study has found that Mexican immigrant mothers experiencing infant mortality with newborns of less than one month old were very unlikely to have returned to Mexico (Hummer et al., 2007) as would be predicted by studies on Hispanic adult mortality.

Previous research has not addressed the possible effect of selective return migration as an explanation for the acculturation paradox since the bulk of this work focuses on differences in health status across first and higher-order generations. Arguably, for this type of research the issue of return migration is of rather muted importance. However, when one studies health status changes within a single generation, the effect of return migration cannot be ignored, particularly since rates of return migration are not trivial. The streams of migrants returning to Mexico each year is significant, yielding cumulated rates of return of up to 50% after 2 years in the US and as high as 70% after 10 years (Reyes, 2001, Massey et al., 2002, Massey and Singer 1995). In addition, the return migration rate varies by characteristics of the migrant, including gender, legal status, and proximity to the US-Mexico border. Migrants who are male, undocumented, or living in states close to the US-Mexico border are more likely to return than migrants who are female, documented, or living in states farther from the border. This suggests that the potential of selective return migration influencing the health status distribution of remaining immigrants is significant. Given these facts, selective return migration on the negative gradient of health outcomes must be considered.

Model and framework

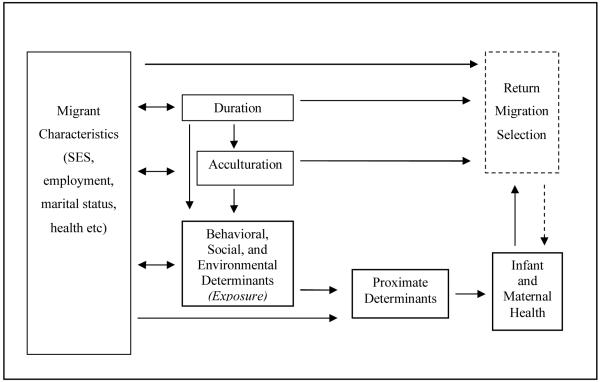

The conceptual model guiding this analysis is illustrated in Figure 1. It includes the mediating influences of socio-cultural determinants—mechanisms through which duration and acculturation affect infant and maternal health in general and birth outcomes in particular. We hypothesize that the acculturative and adaptive process operates through social, behavioral, and environmental conduits (Scribner and Dwyer, 1989, Guendelman et al., 1990, Palloni and Morenoff, 2001). These processes may involve changes in culture (language adoption), tastes and preferences (diet), behaviors (consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs), density of social support, and environmental exposure (living conditions, occupational exposure). Each of these is influenced by, among other factors, duration of residence and the degree to which immigrants are either willing or required to alter tastes and behaviors for adapting to the host country. These factors in turn influence the proximate determinants that directly affect maternal and infant health such as substandard nutrition, smoking, alcohol consumption, and timing and uptake of prenatal care during pregnancy (Coonrod et al., 1995, Cobas et al., 1996, Zambrana et al., 1997).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the effect of duration and acculturation on infant and maternal health.

While duration and acculturation are likely to be highly correlated, they are different dimensions and should be treated separately. One could think of acculturation as a stock that accumulates over time based on the individual’s rate of acculturation and the length of residence. The rate of acculturation is a function of both the propensity and the ability to acculturate and these, in turn, depend on a number of individual characteristics (including migration cohort, level of education, social class of origin, facility with language, neighborhood of residence, and original aspirations). Thus, while long duration is not a precondition for acculturation, all things equal, it works in its favor. Furthermore, there is the possibility that acculturation itself promotes longer duration, so that those who acculturate more rapidly may tend to stay longer. For these reasons we treat duration and acculturation separately, so that duration is associated with behavioral, social, and environmental determinants that need not be due to acculturation. Furthermore, duration influences and is influenced by migrant characteristics such as socioeconomic status, employment, marital status, and health. It also directly affects the likelihood of return migration: the longer the duration, the lower the rate of return migration.

In order to properly assess the effects of duration and acculturation, this framework suggests we must control for conditions (migrant characteristics) that can influence both of them. If we do not do so, we will face endogeneity problems and could mistakenly attribute effects to duration and acculturation that result from health-relevant migrant characteristics. The model also suggests that to understand the mediating pathways through which duration and acculturation influence health status we must identify effects associated with behavioral, social, and environmental determinants as well as the more proximate determinants of health status. Finally, the conceptual model highlights the unobserved process of return migration that is implicated in the observed outcome. Return migration is affected by both duration and acculturation via the behavioral, social, and environmental determinants, as well as migrant characteristics. While we are unable to address selective return migration explicitly in this analysis, we do investigate its effects indirectly. In a separate siblings analysis of this data (Ceballos and Palloni 2010a) we find indirect evidence that this process may be operating,

Methods

Description of the data

We use data from a survey of Mexican-origin women living in two predominantly Mexican communities located in two large Midwestern cities, Chicago and Milwaukee. Several features of the survey data make them unique and optimal for this study of duration, acculturation, and health. First, the data were collected in collaboration with two community clinics that are well-established local health providers, offering comprehensive medical services to large and growing Spanish-speaking communities. Second, the data contain information on infant and maternal health before, during, and after the pregnancy, including birth outcomes, the mother’s pregnancy history and previous pregnancies. Third, the data include information on a range of characteristics associated with infant and maternal health, including maternal health behaviors, socioeconomic status, socio-demographic characteristics, migration history, and acculturation.

The information was collected on two random samples (one in each community) with a total of 539 women drawn from the rosters of two prenatal clinics between 1999 and 2001. Eligible women included all those who were pregnant at the time of the interview or who had just completed a pregnancy immediately prior to the interview. The same survey questionnaire was administered by trained staff members of both clinics, thereby reassuring respondents of confidentiality, improving the reliability of the responses, and increasing the rate of response (only eight potential respondents refused to participate in the study). We were also given access to medical records of the pregnancy and birth.

Clinic staff with ties to the community reported that the clientele is representative of the two Latino communities from these areas because both clinics provide free prenatal services to low-income mothers, employ Spanish-speaking staff with strong community-based ties, and draw broadly from the populations within the communities, including from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Hence, we are confident that the sample is broadly representative of the sociodemographic characteristics of this population. Indeed, interviews with clients and clinic personnel strongly suggest that there were very few women, if any, with impaired health and high-risk pregnancies living in the communities who would choose to bypass the clinics’ services to receive prenatal care directly from the local hospitals. We also conduct a replication analysis below with nationally representative data to further determine applicability of these results to the general Latino population.

We find the sample to have significantly healthier birth outcomes (2% vs. 5% low birth weight and 4% vs. 11% pre-term birth delivery) than the national averages for the Mexico-born population. This may be due to the significantly higher level of prenatal care received by the sample respondents as compared to the national averages: 87% as compared to 61% received adequate levels of prenatal care. Furthermore, the clinics focus on prenatal education that targets the Spanish-speaking population may also have contributed positively to the birth outcomes of the clients.

The sample is limited to Mexican-origin women living in the US who were born in Mexico and who had complete information on all relevant variables. Altogether we retain a sample size of 404 women out of 539. Table 1 describes the variables to be analyzed. While it is useful to compare the characteristics of both samples, because of small sample size, there is not sufficient statistical power to compare them meaningfully. However, a comparison of these two Latino populations with national data shows (analysis not shown here) that aside from age, these two populations are not significantly different on the characteristics of birth outcomes, parity, prenatal care, marital status, and education. Therefore, both samples will be analyzed together. To address any potential differences in the main model, a dichotomous variable distinguishing the two communities is included. Finally, a comparison of characteristics between deleted (cases with missing on the dependent variable) and included cases (cases without missing on both the dependent and independent variables) reveals that while there were significant differences in three variables namely maternal health, parity, and age, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the main model (Appendix, Table A.1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables (n = 404)

| Variable | mean | s.d. | min | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth outcomea (favorable = 1) |

0.91 | 0 | 1 | |

| Years lived in the US | 6.63 | 5.09 | 1 | 28 |

| Acculturation scale | −0.15 | 0.66 | −0.5 | 3.10 |

| Diet (healthy = 1) | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | |

| Tobacco, alcohol, drugs | 0.07 | 0 | 1 | |

| Social support | 0.14 | 0 | 1 | |

| Stress | 0.73 | 0 | 1 | |

| Prenatal care | 0.86 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mother’s health (excellent/very good = 1) |

0.43 | 0 | 1 | |

| Parity (zero parity = 1) | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mother’s age | 26.56 | 5.56 | 15 | 45 |

| Marital status (married = 1) |

0.63 | 0 | 1 | |

| Schooling (10+ years) | 0.38 | 0 | 1 | |

| Income (≥ 150% of poverty level) |

0.14 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mother employed | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | |

| Sample location (Chicago = 1) |

0.87 | 0 | 1 |

Birth outcome is measured by the combination of birth weight, gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and the fetal growth ratio.

We also estimated our main models using all cases and imputing missing values of variables among the deleted cases. Even in extreme cases, where the missing values were the dependent variables (health outcomes), estimation alternatively imputing favorable and unfavorable outcomes resulted in estimates of effects that were almost identical to those obtained from the reduced sample. Hence, from here on we will only work with the reduced sample (for a complete description of the analysis see Ceballos and Palloni, 2010b).

Assessing health outcomes

The literature on the epidemiological and acculturation paradoxes relies primarily on measuring birth outcomes using birth weight, gestational age, or infant mortality. In this study we use a combined approach that includes intrauterine growth, birth weight, and gestational age (Frisbie et al., 1996). First, we construct the indicator of fetal growth ratio (FGR) (Balcazar, 1993) to determine cases with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). An IUGR birth equals zero if FGR is less than the 0.85 threshold, and one if not. Second, we construct a zero/one indicator using birth weight with the conventional 2500 grams set as a cut-off point (zero equals low birth weight). Third, we define a binary variable for gestational age using 37 weeks as the cut-off point (zero equals a preterm birth). Births in the sample are then assigned to one of two classes: favorable health (one) and unfavorable health (zero). A birth outcome is assigned as favorable (dependent variable equal to one) if all of the aforementioned indicators are assigned a value of one and unfavorable (dependent variable equal to zero) otherwise. Ninety-one percent of the sample has favorable outcomes (see Table 1).

Independent variables

The two main independent variables of interest are length of time lived in the US and acculturation. Duration is based on the respondents reported date of entry and the number of years living in the US. The average duration lived in the US is 6.6 years, with over half of the sample having lived in the US for less than 6 years.

We develop an acculturation scale based on the Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area (LAECA) scale using 13 items measuring language usage, proficiency, and fluency in addition to ethnic identity (Burnam et al., 1987). The scale is based on questions asked of the respondents about the language they rely upon (Spanish only, English and Spanish, English only) in various settings, including with immediate family, close relations, and community members; while reading magazines or newspapers; and watching television or listening to the radio. Mean imputation was conducted for those scale items in which 1% to 17% of the cases were missing with no significant effect on the overall results of the main model. The scale also includes the respondent’s ethnic identification: Mexican American or Chicano, Hispanic or Latino, or Non-Hispanic. The items of the scale are standardized and range from −0.5 to 3.1 with an average score of −0.15. The Cronbach alpha score of 0.94 provides evidence of a high level of reliability for this scale. Although we present results obtained when the continuous score of acculturation is used, all results are invariant if one had used instead a dichotomous variable capturing some of the clustering detected in the sample. Furthermore, while the ability to explain most of the variance of acculturation is considered a strength of language-based scales, we also acknowledge its limitations due to the complexity and multi-dimensionality of the concept (Marin, 1992, Marin and Gamba, 1996, Lara et al., 2005).

To control for the behavioral, social, and environmental determinants and the migrant characteristics in the model (see Figure 1), our analysis also includes variables reflecting conditions associated with duration and the acculturation process, including diet, health and health behaviors, levels of stress, social support, and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (Scribner and Dwyer, 1989, Guendelman et al., 1990, Coonrod et al., 1995, Cobas et al., 1996, Zambrana et al., 1997, Palloni and Morenoff, 2001). Diet is based on responses to questions of daily dietary habits. It is measured as a dichotomous variable distinguishing healthy from unhealthy diets (1 if a healthy diet and 0 otherwise). A healthy diet consists of routine consumption of foods rich in protein, calcium, and vitamins such as dairy products; fruits and vegetables; and beef, poultry, and fish. Forty-eight percent of the respondents reported having a healthy diet. Because the use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs is a rare event among pregnant Mexican-origin women in these two communities, we created a composite variable to measure high-risk behaviors for pregnant mothers. The variable equals one if the respondent used or was exposed to smoking tobacco or marijuana, or consumed alcohol during or after the focal pregnancy and zero otherwise. As expected these high risk behaviors are rare (7%) in this sample of Mexican immigrant mothers. Social support measures whether or not the respondent receives help with childcare and housework from her spouse or partner and/or her parents. A binary variable is created measuring whether the respondent reported having at least four such experiences of support (1 if yes, 0 otherwise). Fourteen percent reported experiencing this level of social support. The stress variable is based on a sum of scores assigned to the response (always, sometime, never) to questions probing for feelings or experiences of isolation and loneliness, contempt by others, threat, unfair treatment, or being surrounded by unfriendly people. A dichotomous measure is created where one equals having ever experienced any one of these feelings and zero otherwise. Seventy-three percent of the respondents reported experiencing at least one of these feelings.

Prenatal care is measured by the timing of prenatal care services received during the pregnancy, based on the Kotelchuck Adequacy of Initiation of Prenatal Care scale (Kotelchuck, 1994). A dichotomous variable is constructed with 1 equaling a level of “adequate” prenatal care according to the Kotelchuck scale and 0 otherwise. In this sample 43% report being in very good to excellent health, 26% report this as their first birth, and 86% report receiving adequate prenatal care. Mean imputation was conducted for missing values of 4% of this latter variable using several related prenatal care measures with no significant effect on the main results. To measure maternal health we use the respondent’s own health assessment: 1 if her health is excellent to very good, 0 otherwise. Maternal parity is measured with a dichotomous variable for mothers indicating that this was their first pregnancy (1 if first pregnancy, 0 otherwise).

Age may also moderate the relationship between duration and birth outcomes. According to the “weathering hypothesis,” racial minorities, including Latinos, experience increasing prenatal risks with age due to a cumulative deterioration in health as a consequence of socioeconomic inequality, racial discrimination, and exposure to environmental hazards (Geronimus, 1992, Geronimus, 1996, Rich-Edwards et al., 2003). Thus, deterioration in birth outcomes may be associated with maternal age. Studies have also found age and birth outcomes to be curvilinearly related, the youngest and oldest mothers experience worse outcomes (Reichman and Pagnini 1997). Finally, age may also be positively related to duration, those immigrants with longest residence may also be older than the average immigrant. However, analysis of age, duration, and birth outcomes showed no statistically significant relationship among these variables (result not shown here). Hence, mother’s age is included in the model as a continuous variable. The average age of the respondents is 26.6 years.

Finally, other demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental measures included in the model are the mother’s marital status, 63% are married (1 = married, and 0 = unmarried), schooling, 38% have at least 10 years of schooling (10 years of schooling or greater = 1, and 0 = less than 10 years), and employment status, 47% of the mothers are employed (employed = 1, not employed = 0). The family income variable measures the level of income relative to the poverty level, 14% reported having income that is 150% or greater than the poverty level (150% or greater than the poverty level equals 1, and 0 otherwise). Because of high levels of missing values in this variable (27%), mean imputation was conducted based on related economic variables. There was little significant difference in the results of the main model with and without the imputation. Finally, we also include a dummy variable to distinguish the two surveyed communities (Chicago = 1, and Milwaukee = 0). Eighty-seven percent of the sample lived in Chicago.

Results

We describe two sets of results. The first corresponds to estimates from the sample of mothers in both communities and the second compares the estimates of this sample with those obtained using the Mexican-origin population included in the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). This analysis will test the conceptual model that explains the mediating effects of social and cultural determinants through which duration and acculturation affect infant and maternal health. We first estimate the effects of duration and acculturation on birth outcomes. Since no significant relationship was found between acculturation and birth outcomes (results not shown here) we begin first with the estimate of duration on the birth outcomes variable alone, in Model A, to determine if its effects are mediated by acculturation in Model B. We will then test the mediation of the variables representing the acculturation hypothesis: health behaviors (diet, smoking, alcohol and drug consumption), social support, and stress in Model C. This hypothesis would predict that the inclusion of these measures will reduce the effect of duration and acculturation on birth outcomes. Lastly we add control variables measuring maternal health (prenatal care, maternal health, parity, and age) in Model D, and socioeconomic, demographic, and community determinants (marital status, schooling, income, employment, and sample location) in Model E.

Maternal-infant models estimated in the two communities

Preliminary linear regression analysis provided initial evidence of a nonlinear pattern between years of residence and birth weight (results not shown here). Further analysis was conducted to determine if this relationship persists when using the composite birth outcome variable and to locate the precise duration intervals in which the pattern occurs. The following three intervals were found to be significant and are used in the final analysis: 0 to 3 years, (32% of the sample), 4 to 12 years (57%), and 13 or more years (11%).

Table 2 displays estimates of effects (and associated standard errors) from alternative logistic regression models with the composite birth outcome variable. In all cases the dependent variable is zero for unfavorable health outcomes and one otherwise. Thus, odds ratios less than one indicate the contribution to unfavorable health. Model A shows that mothers of shortest (less than 4 years) and longest (more than 12 years) durations of stay in the US are approximately two-thirds more likely (OR = 0.35 and OR = 0.32, respectively) to experience poorer outcomes than those with intermediate durations, that is, the effects of duration are concave downward. The inclusion of the indicator for acculturation (Model B) does nothing to change this pattern and, in addition, reveals that acculturation leads to somewhat better health status, although the magnitude of the effect is not statistically significant. A bivariate analysis (results not shown here) with acculturation alone was also found not to be statistically significant, and the magnitude of the effect differed little (OR = 1.33) from that shown in Model B.

Table 2.

Logistic regression odds ratio estimates of favorable birth outcomea on duration, acculturation, and behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of the sample data.b

| Variable | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-3 years in the US (4-12 years omitted) |

0.35 ** (0.14) |

0.37 * (0.15) |

0.36 * (0.15) |

0.35 * (0.16) |

0.29 ** (0.14) |

| 13+ years in the US | 0.32 * (0.17) |

0.28 * (0.15) |

0.32 * (0.19) |

0.28 * (0.17) |

0.26 * (0.17) |

| Acculturation scale | 1.38 (0.48) |

1.33 (0.51) |

1.37 (0.53) |

1.56 (0.70) |

|

| Diet (healthy = 1) | 2.25 * (0.88) |

2.24 * (0.88) |

2.73 * (1.15) |

||

| Tobacco, alcohol, drugs | 0.46 (0.26) |

0.48 (0.28) |

0.49 (0.30) |

||

| Social support | 6.10 † (6.30) |

6.78 † (7.11) |

5.34 (5.74) |

||

| Stress | 0.49 (0.25) |

0.45 (0.24) |

0.42 (0.24) |

||

| Prenatal care | 0.70 (0.37) |

0.66 (0.38) |

|||

| Mother’s health (excellent/very good = 1) |

1.16 (0.44) |

1.22 (0.49) |

|||

| Parity (zero parity = 1) | 1.34 (0.62) |

1.18 (0.59) |

|||

| Mother’s age | 1.02 (0.04) |

1.00 (0.04) |

|||

| Marital status (married = 1) | 2.21 † (0.90) |

||||

| Schooling (10+ years) | 0.96 (0.39) |

||||

| Income (≥ 150% of poverty level) |

0.22 ** (0.12) |

||||

| Mother em ployed | 2.40 † (1.09) |

||||

| Sample location (Chicago = 1) |

3.20 * (1.55) |

||||

| Log likelihood | −116.91 | −116.40 | −109.53 | −109.06 | −100.75 |

| Likelihood Ratio χ2 | 8.96 † | 9.97 † | 23.73 ** | 24.66 † | 41.28 *** |

| Degrees of freedom | 2 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 16 |

p<=.10

p<=.05

p<=.01

p<=.001.

Birth outcome is measured by the combination of birth weight, gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and the fetal growth ratio.

Standard errors are in parentheses, n = 404.

So far we have established one fact: birth outcomes are initially unfavorable, improve within a few years of having migrated, and then deteriorate sharply after 12 years of residence. We stated before that while duration and acculturation may be highly correlated they reflect different dimensions. The results in Table 2 show that these different dimensions are expressed as different health effects; duration benefits health over the short term but impairs it over the long term, while acculturation is broadly beneficial, although not statistically significant. What can we say about the mediating mechanisms?

Model C includes those social and behavioral factors that are hypothesized to be associated with acculturation and health, including healthy diet; tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use; social support; and stress. The effects associated with each of them are in the expected direction, but only two variables are significant: healthy diet is at the .05 level and social support is marginally significant at the 0.10 level. Hence, controlling for the intermediate pathways enhances the direct effects of duration (at short durations) and leaves the effects of acculturation unchanged. The fact that the gross effects of duration and acculturation are not attenuated upon controlling for intermediate pathways suggests that these variables are not the most important mediators. A test of the mediation using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) showed no statistically significant mediation occurring between duration and birth outcomes by any of the behavioral variables (results not shown here).

Adding maternal characteristics in Model D and socioeconomic and demographic variables in Model E shows that while some of these variables are significantly associated with birth outcomes (including marital status, income, employment status, and sample location) they do not attenuate the effects of duration and acculturation.

These results show that birth outcomes experience an initial improvement in the short run and deterioration over the longer term. While they provide some similarities with previous studies on birth outcomes among the first generation, a positive (Balcazar and Krull, 1999) and negative (Guendelman and English, 1995, Zambrana et al., 1997) association between duration and birth outcomes, the difference is that our study shows a curvilinear relationship rather than a linear one. This unique outcome is due in part to the availability of disaggregated duration data and use of a nonlinear methodology. Of course, the effects of duration may also be concealing migration cohort effects: that is, those associated with characteristics of migrants who entered the US at different dates. As the study focuses on the effects of duration, we do not address cohort effects in the present analysis.

Furthermore, we are unable to identify mediating pathways through which these effects take place. There is no attenuation of the estimates of duration or acculturation when measures of behavioral profile, exposure to stress, social relations, maternal characteristics, and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are added to the model. This absence of effects of acculturation and the lack of evidence for effective mediating pathways are entirely consistent with the return migration conjecture. We next determine the generalizability of these results by conducting a similar analysis using a nationally representative sample.

Comparisons with estimates from a national sample of Mexicans in the US

To ensure that our inferences are not overly dominated by the uniqueness of the samples we use, we conducted a comparable analysis using data from a national sample: the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth Cycle V (NSFG V), a complex sample survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NSFG V survey includes data on family growth, formation, dissolution, and reproductive history, maternal health and social characteristics, including duration in the US and language for 10,847 women from age 15 to 44 years (Mosher, 1998). The sample includes 1553 Latinas from nearly every state and all of the largest metropolitan areas in the US. In this analysis we select all Mexican-origin mothers with children 0-9 years old—a total of 190 mothers representing a population of 724,621 (based on the STATA 10.1 estimates for a complex survey design with weighted data that contain 4 strata and 51 probability sampling units).

There are important differences between the selected NSFG V population of mothers and those from our sample of the two Midwestern communities. Unlike the communities’ sample, the NSFG V infant birth data is based on retrospective information and might conceivably be affected by recall errors. As recall errors should increase with the age of the child, inferences drawn using a subsample of the most recently born should lead to more robust inferences. However, in an analysis with such a subsample (results not shown here) we found no differences in the results when compared with the entire sample. In addition, while those in the national sample have on average lower levels of favorable birth outcomes (82% vs. 91%), possibly as a result of a longer average duration of residence in the US (10 years vs. 6.6 years) they also have characteristics associated with more favorable outcomes: a higher level of education (46% vs. 38% have completed some high school); a higher rate of marriage (76% vs. 63%); and a lower level of first parity pregnancies (14% vs. 26%). Thus, we may expect the relationship of birth outcomes to duration may be attenuated in the interval with more favorable birth outcomes.

Table 3 displays estimates using the NSFG V data of a model analogous to those in Table 2. All available indicators used in the national sample were constructed to maximize similarity to the variables used in the analysis of our main sample. The results show remarkable similarities in the association between US residential duration and birth outcomes. While the duration intervals used are not the exact same as those of the community sample analysis, this nevertheless is a strong indication of the existence of a nonlinear relationship between duration and birth outcomes among Mexican immigrants. In particular, the effects of duration are concave downward and negative at both the shortest and longest duration, as in our local sample, and similarly, the indicator of acculturation is positively associated with birth outcomes, but is not statistically significant. Finally, adding behavioral and social measures has little effect on the main model and the effect of the shortest and longest durations on birth outcomes becomes statistically significant after controlling for other covariates.. In sum, the direction and magnitude of effects as well as all the inferences drawn from this national sample are either the same or broadly consistent with those obtained from the two communities. This provides support for the generalizability of the results from our study’s samples.

Table 3.

Logistic regression odds ratio estimates of birth outcomea on duration, acculturation, and social determinants of 1995 NSFG V sample.b

| Variable | Model A | Model B | Model C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-6 Years in the U.S. (7-10 years omitted) |

0.33 (0.23) |

0.34 (0.24) |

0.26 * (0.17) |

| 11+ Years in the U.S. | 0.38 (0.24) |

0.36 † (0.21) |

0.25 * (0.16) |

| Acculturation (medium/high = 1) |

1.54 (0.63) |

1.64 (0.66) |

|

| Smoking | 0.67 (0.40) |

||

| Stress | 0.83 (0.42) |

||

| Parity (zero parity = 1) | 0.29 ** (0.12) |

||

| Marital status (married = 1) | 2.26 (1.20) |

||

| Schooling (10+ years) | 0.91 (0.27) |

||

| F-distribution | 1.43 | 3.76 * | 4.92 *** |

| Design degrees of freedom | 2 | 3 | 8 |

p<=.10

p<=.05

p<=.01

p<=.001.

Birth outcome is measured by the combination of birth weight, gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and the fetal growth ratio. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Based on the STATA 10.1 estimates for complex survey design with weighted data, that contain 4 strata and 51 probability sampling units, the sample represent a population = 724,621. The model contains design degrees of freedom equal to 47 and linearized standard errors (in parentheses), n = 190.

Discussion

This study assesses the hypotheses explaining the deterioration in the apparent health advantage experienced by Hispanic immigrants in the United States through an examination of changes in birth outcomes during the first generation. In particular, we investigate the effects of duration, acculturation and the potential existence of selective return migration.

Using data collected in two predominantly Mexican-origin communities located in the Midwest, we found evidence of a nonlinear relationship between duration in the US and birth outcomes. Mexican immigrant women who had lived in the US for 13 or more years were approximately 75% less likely to have favorable birth outcomes as those who had lived in the US for 4 to 12 years. In addition, women who had lived in the US fewer than 4 years were nearly 70% less likely to have favorable birth outcomes as compared to the reference group.

To evaluate the generalizability of our results from the two local samples, we conducted a confirmatory analysis using a national sample of Mexican immigrants. In the national sample, women living in the US less than 7 years and more than 10 years were also approximately 75% less likely to have favorable birth outcomes as were those who had lived in the US 7 to 10 years. The results from this analysis provide support for the representativeness of our finding of the curvilinear association of duration and birth outcomes in our local samples of the Mexican immigrant population.

While our analysis of cross-sectional data from the two local samples and one national sample of Mexican immigrant mothers support the pattern of the acculturation paradox (the idea that at longer durations, health outcomes deteriorate), we find no evidence to support the idea that unfavorable birth outcomes are caused or mediated by conditions that are normally thought to accompany the acculturation process. Controlling for the effects of behavioral and social determinants does not reveal evidence that these variables attenuate the effect of duration or acculturation on birth outcomes. Rather, these results indirectly suggest a selective return migration based on health status.

The curvilinear relationship between duration and birth outcomes found in this study differs from the findings of previous intragenerational studies of Mexican immigrants that have found linear relationships with both positive (Balcazar and Krull, 1999) and negative (Guendelman and English, 1995, Zambrana et al., 1997) associations between length of stay and birth outcomes. The unique outcomes of our study can be explained in part by a nonlinear analysis of disaggregated duration data. It may also be that we have captured two different processes operating simultaneously. Perhaps at shorter durations immigrants go through an adjustment period as newcomers, experiencing higher levels of stress and having far less access to resources that contribute to a healthy pregnancy and birth, whereas at the longer durations such lower birth outcomes may be due to health selective return migration. It may also be the case that there are two different return migration selection mechanisms occurring over time: at short durations, those with poor health are more likely to return to Mexico because more dependable sources of social support and healthcare are available to them, but at longer durations, they are more likely to remain in the US, having improved healthcare access over time. In addition, the decline in birth outcomes over the longer duration may also be due to negative acculturation effects that were unable to be unaccounted for in this analysis. Finally, the curvilinear relationship may be a combination of each of these processes.

Several limitations to this study must be noted. As this evidence is indirect the acculturation process cannot be entirely ruled out. The lack of a mediation effect from behavioral and social determinants may be associated with inadequately measured or omitted variables. For example, language and ethnic identity-based acculturation measures may inadequately capture the complexity and multidimensionality of the concept. Furthermore, the fact that this is a study of a healthy segment of the population in which poor outcomes are rare, the sample size may influence the result. To gain more variance in the birth outcome variable, future studies would benefit by the inclusion of a broader measure of neonatal health, such as, heart rate lung sounds; abdominal and neurological examinations; muscle tone; and ability to suckle.

A final caveat is important to consider. All of our results are based on first generation migrants. Therefore, they do not run counter to previous studies of the acculturation paradox, which primarily considered the effects across generations. Indeed, it is unlikely the deterioration in birth outcomes across generations would be due to selective return migration, since return migration is improbable among second or higher-order generation immigrants.

This study provides evidence that when considering the relationship of health status and length of residence among first generation Latinos in the United States, the acculturation hypothesis alone may be an insufficient explanation. Our results provide indirect support of the return migration hypothesis and points to the necessity for further research to better understand the changing health status among Hispanic immigrants in the US and its relationship to acculturation and selective return migration.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. SES-0082704), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant No. 3-F31-HD08740-02), funding from the International Migration Program of the Social Science Research Council with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors acknowledge appreciation for the contribution to this project by Robert E. Jones, Jeffrey Morenoff, Mary Sommers, Shawn Kanaiaupuni, and Kristin Espinosa, and for comments on earlier versions by Gustavo Carlo, Lory J. Dance, Marcela Raffaelli, Kimberly A. Tyler, and J. Allen Williams. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of these individuals, agencies, or foundations.

Appendix

Table A.1.

Comparisona of variable means for missing and non-missing cases

| Variable | Missing cases | Non-missing cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | n | mean | n | |

| Years lived in the US | 6.50 | 58 | 6.96 | 437 |

| Acculturation scale | −0.21 | 58 | −0.10 | 436 |

| Diet (healthy = 1) | 0.47 | 57 | 0.47 | 417 |

| Tobacco, alcohol, drugs | 0.12 | 59 | 0.08 | 437 |

| Social support | 0.15 | 59 | 0.14 | 435 |

| Stress | 0.78 | 58 | 0.72 | 436 |

| Prenatal care | 0.88 | 59 | 0.87 | 437 |

| Mother’s health (excellent/very good = 1) |

0.21 *** | 58 | 0.43 | 427 |

| Parity (zero parity = 1) | 0.12 * | 59 | 0.28 | 437 |

| Mother’s age | 27.73 * | 59 | 26.41 | 437 |

| Marital status (married = 1) | 0.61 | 59 | 0.62 | 436 |

| Schooling (10+ years) | 0.32 | 59 | 0.38 | 437 |

| Income (≥ 150% of poverty level) |

0.07 | 58 | 0.14 | 437 |

| Mother employed | 0.43 | 58 | 0.49 | 437 |

p<=.10

p<=.05

p<=.01

p<=.001.

Comparing means of missing cases relative to non-missing cases using T-test (for continuous variables) and Fisher’ Exact test (for dichotomous variables).

References

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” And healthy migrant hypotheses. American journal of public health. 1999;89(10):1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams B, Guendelman S. Nutrient intake of Mexican American and non-Hispanic white women by reproductive status: results of two national studies. Journal of the American dietetic association. 1995;95(8):916–918. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(95)00253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Soobader M-J, Berkman LF. Low birthweight among us Hispanic/Latino subgroups: the effect of maternal foreign-born status and education. Social science & medicine. 2007;65(12):2503–2516. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akresh IR, Frank R. Health selection among mew immigrants. American journal of public health. 2008;98(11):2058–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba R, Nee V. Rethinking assimilation theory for a new era of immigration. International migration review. 1997;31(4):826–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht SL, Clarke LL, Miller MK, Farmer FL. Predictors of differential birth outcomes among Hispanic subgroups in the United States: The role of maternal risk characteristics and medical care. Social science quarterly. 1996;77(2):407–433. [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H. Mexican Americans’ intrauterine growth retardation and maternal risk factors. Ethnicity & disease. 1993;3(2):169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Aoyama C, Cai X. Interpretative views on Hispanics’ perinatal problems of low birth weight and prenatal care. Public health reports. 1991;106(4):420–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Krull JL. Determinants of birth-weight outcomes among Mexican-American women: examining conflicting results about acculturation. Ethnicity & disease. 1999;9(3):410–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Krull JL, Peterson G. Acculturation and family functioning are related to health risks among pregnant Mexican American women. Behavioral medicine. 2001;27(2):62–70. doi: 10.1080/08964280109595772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra JE, Hogue CJR, Atrash HK, Perez N. Infant-mortality among Hispanics - a portrait of heterogeneity. Journal of the american medical association. 1991;265(2):217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam AM, Hough RL, Telles CA, Karno M, Escobar JI. Measurement of acculturation in a community population of Mexican Americans. Hispanic journal of behavioral science. 1987;9(2):105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos M, Palloni A. Center for Demography and Ecology Working Paper. University of Wisconsin – Madison; 2010a. Selective return migration and the maternal and infant health of the Mexican-origin population in the United States: A siblings’ analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos M, Palloni A. Center for Demography and Ecology Working Paper. University of Wisconsin – Madison; 2010b. Maternal and infant health of the Mexican-origin population in the United States: the role of acculturation, duration, and selection. [Google Scholar]

- Cobas JA, Balcazar H, Benin MB, Keith VM, Chong YN. Acculturation and low-birthweight infants among Latino women: a reanalysis of HHANES data with structural equation models. American journal of public health. 1996;86(3):394–396. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW, Jr., David RJ. Pregnancy outcome of Mexican-American women: The effect of generational residence in the United States. Ethnicity & disease. 2004;14(3):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JW, David RJ, Mendivil NA, Wu SY. Intergenerational birth weights among the direct female descendants of US-born and Mexican-born Mexican-American women in Illinois: An exploratory study. Ethnicity & disease. 2006;16(1):166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod DV, Balcazar H, Brady J, Garci S, Van Tine M. Smoking, acculturation, and family cohesion in Mexican American women. Ethnicity and disease. 1995;9(3):434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa IA. Perinatal outcomes among Mexican Americans: A review of an epidemiological paradox. Ethnicity & Disease. 2002;12(4):480–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durden TE. Nativity, duration of residence, citizenship, and access to health care for Hispanic children. International migration review. 2007;41(2):537–545. [Google Scholar]

- English PB, Kharrazi M, Guendelman S. Pregnancy outcomes and risk factors in Mexican Americans: the effect of language use and mother’s birthplace. Ethnicity & Disease. 1997;7(3):229–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethnicity & disease. 2001;11(3):496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbie WP, Forbes D, Pullum SG. Compromised birth outcomes and infant mortality among racial and ethnic groups. Demography. 1996;33(4):469–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & disease. 1992;2(3):207–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Social science & medicine. 1996;42(4):589–97. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Kimbro RT, Turra CM, Pebley AR. Socioeconomic gradients in health for white and Mexican-origin populations. American journal of public health. 2006;96(12):2186–2193. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Abrams B. Dietary, alcohol, and tobacco intake among Mexican-American women of childbearing age: results from HHANES data. American journal of health promotion. 1994;8(5):363–372. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-8.5.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Abrams B. Dietary intake among Mexican-American women: generational differences and a comparison with white non-Hispanic women. American journal of public health. 1995;85(1):20–25. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, English PB. Effect of United States residence on birth outcomes among Mexican immigrants: an exploratory study. American journal of epidemiology. 1995;142(9 Suppl):S30–S38. doi: 10.1093/aje/142.supplement_9.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, Gould JB, Hudes M, Eskenazi B. Generational differences in perinatal health among the Mexican American population: findings from HHANES 1982–84. American journal of public health. 1990;80(Suppl.):61–65. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley K, Eskenazi B. Time in the United States, social support and health behaviors during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent. Social science and medicine. 2006;62(12):3048–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SG, Harvey C, Montes H, Nickens H, Cohen BH. Patterns of cigarette smoking among Hispanics in the United States: Results from HHANES 1982–84. American journal of public health. 1990;80(Suppl.):47–53. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Powers DA, Pullum SG, Gossman GL, Frisbie WP. Paradox found (again): Infant mortality among the Mexican-origin population in the United States. Demography. 2007;44(3):441–457. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G, Massey DS, Rosenzweig MR, Smith JP. Immigrant health: selectivity and acculturation. In: Bulatao RA, Cohen B, Anderson NB, editors. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2004. pp. 227–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana’iaupuni SM, Donato KM, Thompson-Colon T, Stainback M. Counting on kin: social networks, social support, and child health status. Social forces. 2005;83(3):1137–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed adequacy of prenatal care utilization index. American journal of public health. 1994;84(9):1414–1421. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Gorman BK. Immigration and infant health: Birth outcomes of immigrant and native-born women. In: Hernandez DJ, editor. Children of immigrants: health, adjustment, and public assistance. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 244–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual review of public health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclere FB, Jensen L, Biddlecom AE. Health care utilization, family context, and adaptation among immigrants to the United States. Journal of health and social behavior. 1994;35(4):370–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G. Issues in the measurements of acculturation among Hispanics. In: Geisinger KF, editor. Psychological testing of Hispanics. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1992. pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measure of acculturation for Hispanics: the bidimensional scale for Hispanics. Hispanic journal of behavioral science. 1996;18(3):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public health reports. 1986;101(3):253–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey D, Durand J, Malone NJ. Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2002. Breakdown: Failure in the post-1986 US immigration system; pp. 105–141. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Singer A. New estimates of undocumented Mexican migration and the probability of apprehension. Demography. 1995;32(2):203–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher WD. Design and operation of the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Family planning perspectives. 1998;30(1):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41(3):385–415. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Ewbank DC. Selection processes in the study of racial and ethnic differentials in adult health and mortality. In: Bulatao RA, Cohen B, Anderson NB, editors. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2004. pp. 171–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Morenoff JD. Interpreting the paradoxical in the Hispanic paradox: demographic and epidemiologic approaches. Annals of the New York academy of sciences. 2001;954:140–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park RE, Burgess EW. Introduction to the science of sociology. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman Nancy E., Pagnini Deanna L. Maternal age and birth outcomes: Data from New Jersey. Family planning perspectives. 1997;29(6):268–272. 295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BI. Immigrant trip duration: the case of immigrants from western Mexico. International migration review. 2001;35(4):1185–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Buka SL, Brennan RT, Earls F. Diverging associations of maternal age with low birthweight for black and white mothers. International journal of epidemiology. 2003;32(1):83–90. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz RJ, Dolbier CL, Fleschler R. The relationships among acculturation, biobehavioral risk, stress, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and poor birth outcomes in Hispanic women. Ethnicity & disease. 2006;16(4):926–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Assimilation and its discontents: between rhetoric and reality. International migration review. 1997;31(4):923–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Dwyer JH. Acculturation and low birthweight among Latinos in the Hispanic HHANES. American journal of public health. 1989;79(9):1263–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden MS, Barrera RE. Maternal support and cultural influences among Mexican immigrant mothers. Families and society: the journal of contemporary human services. 1996;77(M4):298–313. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological methodology. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Teller CH, Clyburn S. Trends in infant mortality. Texas business review. 1974;48:240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana RE, Scrimshaw SC, Collins N, Dunkel-Schetter C. Prenatal health behaviors and psychosocial risk factors in pregnant women of Mexican origin: the role of acculturation. American journal of public health. 1997;87(6):1022–1026. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]