Abstract

Objectives. We examined factors influencing physician practice decisions that may increase primary care supply in underserved areas.

Methods. We conducted in-depth interviews with 42 primary care physicians from Los Angeles County, California, stratified by race/ethnicity (African American, Latino, and non-Latino White) and practice location (underserved vs nonunderserved area). We reviewed transcriptions and coded them into themes by using standard qualitative methods.

Results. Three major themes emerged in relation to selecting geographic- and population-based practice decisions: (1) personal motivators, (2) career motivators, and (3) clinic support. We found that subthemes describing personal motivators (e.g., personal mission and self-identity) for choosing a practice were more common in responses among physicians who worked in underserved areas than among those who did not. By contrast, physicians in nonunderserved areas were more likely to cite work hours and lifestyle as reasons for selecting their current practice location or for leaving an underserved area.

Conclusions. Medical schools and shortage-area clinical practices may enhance strategies for recruiting primary care physicians to underserved areas by identifying key personal motivators and may promote long-term retention through work–life balance.

A critical element of improving population health in underserved areas is the adequacy and distribution of the primary care physician supply.1,2 Trends indicate that fewer medical students are choosing primary care careers, and it is becoming more difficult to recruit and retain primary care physicians in underserved communities.3 Even if the current health care reform debate increases insurance coverage, residents in areas with an inadequate physician supply will still have greater difficulty receiving timely and appropriate clinical care.4 Policymakers at state and federal levels continue to face several challenges to changing the patterns of physician supply to improve population health in underserved areas.5–8

Despite decades of multipronged efforts to address physician distribution in minority and shortage areas, strategies remain limited. Institute of Medicine reports have recommended improving health disparities, health care quality, and access to care through physician workforce solutions.9–11 Personal background, educational factors, and economic incentives influence a physician's practice location. Personal level factors that appear to increase the likelihood of choosing primary care and practicing in a physician shortage area include minority race/ethnicity,12–14 disadvantaged socioeconomic background, and having been raised in a rural area.15–17 Positive exposures to and experiences working with underserved, minority, and immigrant populations during training also increase a physician's likelihood of practicing in an underserved area.17,18 Charles Drew University and the Jefferson Medical College Physician Shortage Area Program recruit on the basis of such factors, and their graduates are more likely to practice in underserved areas.19–21 Similarly, the National Health Service Corps provides economic incentives, including participation in loan repayment programs, that effectively encourage physicians to work in shortage areas.22 Despite the success of these and other individual programs, the number of medical school graduates selecting primary care fields continues to decline and physician geographic maldistribution persists.23

Our objective in this community-based participatory research study, conducted in partnership with key stakeholders in Los Angeles County, was to identify strategies to enhance primary care physician supply in urban underserved settings. Using semistructured physician interviews, we sought to understand factors that contribute to physicians’ decisions to practice in or leave an underserved area.

METHODS

We used a community-based participatory research approach throughout the project's design and execution.24 We formed a 7-member community advisory board (CAB) composed of researchers, medical educators, physician leaders, and community clinic administrators to develop the study protocol, review the analysis, and interpret the results.

We planned 42 interviews with purposeful sampling of physicians from each racial/ethnic category and further stratified them into underserved and nonunderserved settings by using physician reports of their payer mix and practice settings. We defined underserved as working in a census tract or comprehensive clinic that the Health Resource and Service Administration had designated as a health profession shortage area.25

We contacted all physicians who had verified contact information until our study quotas were filled and conducted the one-on-one interviews in a confidential environment.26 Study-eligible physicians reported their race/ethnicity as non-Latino White, African American, or Latino; their specialty as primary care (internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics); and a current practice of more than 20 hours per week in a clinical setting. Our snowball sampling recruitment process started with the CAB for the first wave of study enrollment. To mitigate selection bias, we limited the number of referrals to fewer than 4 per CAB member or participant and excluded duplicate names. CAB members referred 26 individuals, of whom we interviewed 17 physicians on the basis of responses and eligibility. These 17 physicians referred a second wave of 24 clinicians, 18 of whom we interviewed. In the third wave, we interviewed 7 physicians who fulfilled the remaining study quotas. We contacted each referred provider by telephone, e-mail, or both, and gave each provider up to 6 weeks to decline participation or schedule an interview. Of 57 total referrals for open interview slots, 4 physicians were ineligible and 11 did not respond to requests for interviews through e-mail or telephone.

Interviewers were trained in the use of qualitative interviewing techniques27 and used an interview guide that contained open-ended questions and several time-point prompts as well as a short demographic questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and unpaid, and all participants provided verbal consent.

Data Analysis

Digital recordings of interviewers were professionally transcribed. Two research team members (K. O. W. and R. R.) independently analyzed each transcript by using standard qualitative content-analysis methods to identify meaningful quotations. We read transcripts several times in an iterative process to identify recurring concepts that represented all possible physician motivators, which we developed into codes. After independently coding transcripts, we completed between-coder comparisons and compiled the codes into a revised codebook (κ = 82.6%).

We then pile-sorted the coded quotations into smaller categories or subthemes.27 Pile-sorting is a process by which individual quotations are printed onto separate cards, placed on a large flat surface, and then sorted by content area into groups of similar statements. Within each grouping, we selected statements according to relevance and clarity of expression to the subthemes. A fourth investigator (A. F. B.) then reviewed the subthemes for relevance and consistency as the overarching themes emerged. Finally, we examined the key themes and subthemes to evaluate to what degree they were shared across practice location and race/ethnicity.

We analyzed the frequency of themes and subthemes in response to 3 specific questions derived from the pile-sorting method. First, for all physicians, we analyzed themes present in responses to the introductory question “How did you decide to work here?” to investigate factors that might influence recruitment. Next, among those who had practiced in but chose to leave an underserved area, we examined frequency of themes and subthemes present in the responses specifically to identify retention strategies, first examining the responses among those who left work in underserved areas to “Why did you leave?” Finally, among participants in underserved areas who had seriously considered leaving, we examined the frequency of themes and subthemes in their responses to “Why have you considered leaving?”

We used the Fisher exact test to determine the statistical difference between underserved and nonunderserved groups. We report the most salient themes and subthemes found along with selected quotations that exemplify the range of core topics, problems, and concerns. We used Atlas.ti software version 5.2 (Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) to facilitate data management and analysis of the text.

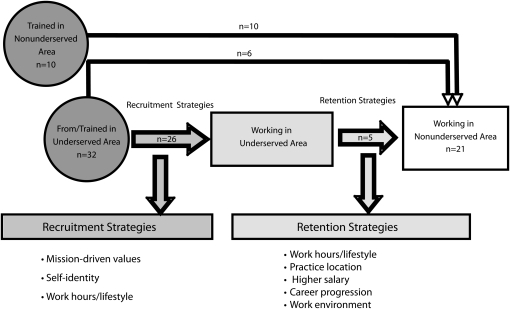

We linked data from the qualitative analysis to information on physician residency and ultimate practice location to develop a framework for factors that influence physician decisions about practice location. To create the flow diagram of the pathway into and out of underserved areas, we examined physicians’ descriptions of residency training location (underserved vs nonunderserved setting), childhood background (description of being from an underserved area or nonunderserved area), and location of positions held since residency (underserved vs nonunderserved setting). We then examined the pathways of physicians who had left underserved areas and those who had seriously considered leaving underserved areas.

RESULTS

The 42 participating primary care physicians ranged in age from 31 to 73 years (mean age 48 years; SD = 12), 45% were women, 56% had no educational debt, and 21% had a loan repayment obligation (Table 1). By specialty, 48% of participants were in internal medicine, 31% were in family medicine, 17% were in pediatrics, and 5% were in other primary care fields. Physicians who practiced in underserved areas were slightly older and were more likely to practice in a community or public clinic than were physicians who practiced elsewhere.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Participant Characteristics: Los Angeles County, CA, 2008

| Total (N = 42), Mean ±SD or % (No. of participants) | Underserved (n = 21), Mean ±SD or % (No. of participants) | Nonunderserved (n = 21), Mean ±SD or % (No. of participants) | |

| Age, y | 48 ±12 | 50 ±14 | 46 ±10 |

| Women | 45 (19) | 43 (9) | 48 (10) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 60 (25) | 57 (12) | 62 (13) |

| Single | 19 (8) | 29 (6) | 10 (2) |

| Divorced | 10 (4) | 10 (2) | 10 (2) |

| Other | 11 (5) | 4 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Income distribution | |||

| < $100 000 | 7 (3) | 5 (1) | 10 (2) |

| $100 000–$149 999 | 26 (11) | 24 (5) | 28 (6) |

| $150 000–$199 999 | 33 (14) | 38 (8) | 28 (6) |

| $200 000–$250 000 | 31 (9) | 19 (4) | 24 (5) |

| > $250 000 | 12 (5) | 14 (3) | 10 (2) |

| Educational debt | |||

| $0 | 48 (20) | 65 (13) | 33 (7) |

| < $100 000 | 29 (12) | 20 (4) | 38 (8) |

| $100 000–$180 000 | 14 (6) | 5 (1) | 24 (5) |

| > $180 000 | 7 (3) | 10 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Refused or not available | 2 (1) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Loan repayment and service obligation | 21 (9) | 24 (5) | 19 (4) |

| Medical education | |||

| California-based school | 69 (29) | 71 (15) | 67 (14) |

| Non-California public school | 76 (32) | 81 (17) | 71 (15) |

| Residency training in California | 69 (29) | 67 (14) | 71 (15) |

| Specialty distribution | |||

| Family medicine | 48 (20) | 52 (11) | 43 (9) |

| Internal medicine | 31 (13) | 19 (4) | 43 (9) |

| Pediatrics | 17 (7) | 24 (5) | 9 (2) |

| Other primary care | 5 (2) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Practice setting | |||

| Staff model HMO or Kaiser | 26 (11) | 10 (2) | 43 (9) |

| Community or public clinic | 31 (13) | 62 (13) | 0 (0) |

| University | 21 (9) | 10 (2) | 33 (7) |

| Private practice | 21 (9) | 19 (4) | 24 (5) |

Note. There were no statistical differences between underserved and nonunderserved physicians, except for practice setting, using the χ2 test (P < .05).

Themes

We identified 1361 statements and coded them into themes and subthemes from the question “How did you decide to work here?” Sample quotations show the range and frequency of the domains and themes (Table 2). Three domains emerged in relation to the selection of current practice location: (1) personal motivators, (2) career motivators, and (3) clinic support. We defined personal motivators as intrinsic influences from the physician's background and personality, personal values, and sense of obligation related to choosing their practice location. We defined career motivators as logistical, personal, and family influences related to selecting a practice location. Clinic support factors were the support that helped with executing physician responsibilities for patient care. We describe each theme in detail, followed by illustrative examples and differences in themes by physician practice location and by race/ethnicity.

TABLE 2.

Themes and Subthemes With Sample Quotations Showing Range of Participant Endorsement: Los Angeles County, CA, 2008

| Domains | Strong Endorsement | Weaker Endorsement |

| Personal growth | “At the time, it offered me the combination that I was looking for in a medical practice and teaching opportunity combined.” (underserved, White, family physician) | “Just to practice medicine and take care of patients and make people better.” (underserved, African American, family physician) |

| Self-identity | “I grew up in the East Los Angeles community … I grew up uninsured … so that was a big motivation to come back and practice in the community here.” (underserved, Latino, family physician) | “I was always irritated … that people [said] because you're not White, that's where you should work.” (nonunderserved, Latino, internist) |

| Mission-based values | “I feel like I have a moral obligation to be here.” (underserved, White, pediatrician) | “You know, I got to tell you, I guess there's a bit of guilt I feel about not being able to do more in the underserved community, but I do feel we all have to balance that out.” (nonunderserved, Latino, internist) |

| Salary and benefits | “It was more money; I was also looking for more money and so this current job paid more money.” (underserved, African American, family physician) | “In fact, I didn't even know what my starting salary was. It didn't matter.” (underserved, Latino, family physician) |

| Work hours and lifestyle | “It also had better hours; I don't have to work weekends anymore, which I did for almost 15 years, so that was an excellent benefit.” (underserved, African American, family physician) | “When we started, we were probably working about, I would say, 70 hours a week. So, it was like being residents again.” (underserved, Latino, family physician) |

| Career satisfaction | “I love my job. I love coming here. The other thing that's very amenable here is that I'm able to do 10-hour days. I don't come here every day.” (nonunderserved, White, internist) | “People may leave for that. I think people usually leave because they burn out. They burn out, or they can't change the system, and it's just time to move on, or they want to do something different.” (nonunderserved, White, internist) |

| Family | “I would have left Los Angeles a long time ago if it wasn't for my parents. My parents’ health needs, they need help.” (nonunderserved, African American, internist) | “I also didn't have a family; I was single. I didn't have children, so I didn't have anybody depending on my income, so I could basically do whatever it was that my heart told me.” (nonunderserved, White, family physician) |

| Geography | “No, I'm from California so I wasn't moving or leaving… . I mean, it did mean a longer drive … but I was used to that.” (underserved, Latino, family physician) | “Probably the only downside of my job is the commute, it's a little bit further than I'd like with the gas prices, but other than that, I'm pretty happy.” (nonunderserved, African American, family physician) |

| Loan repayment programs | “I was involved in a loan repayment program to work at the community health center.” (underserved, African American, family physician) | “They didn't have any loan repayment for this job. That was called, me—pay it with your own check.” (nonunderserved, African American, internist) |

| Work environment | “Respect, a positive work environment—and that includes the physical facility … one needs to make it as soothing, as comforting and as warm and friendly as possible.” (nonunderserved, White, pediatrician) | “I'm currently doing very similar things to what I was doing when the hospital was opened, but … I'm doing it in trailers that used to be personnel trailers … so I've been working in this facility for a while.” (underserved, White, pediatrician) |

| Provider team | “There's also tons of receptionists, there's tons of education coordinators, there's a disability coordinator … so the physician is just kind of guiding the care and to me, that has been a fantastic model.” (nonunderserved, African American, family physician) | “We're not overly staffed. We can't afford it … we kind of just get by with and do whatever we have to do.” (underserved, Latino, family physician) |

| Reimbursement | “In the county system, I had to really see what was the bare minimum I could do for the patients to actually get them to be somewhere in a positive state of health. Here, I have more options because they have coverage… . I have less obstacles in care.” (nonunderserved, Latino, family physician) | “I always know how good I have it because I don't have to worry about a person having a plastic card … I know I have to sometimes really advocate/fight for resources for my patients, but at least they can get in the door, and these people are the most in need.” (underserved, Latino, family physician) |

| Information support | “We have a fantastic electronic record where someone's labs can be forwarded to me easily and I don't need to pull a chart … so I don't necessarily need to be in the office to do those things.” (nonunderserved, African American, family physician) | “ … with the implementation of our electronic medical record … but it also is a lot slower than the old paper records … I think it is eating into a lot of personal time and causes stress and has caused some people to leave.” (nonunderserved, White, family physician) |

Note. Themes and subthemes were developed from respondents’ answers to study protocol questions, including “How did you decide to work here?” and questions asked for 3 scenarios: before you worked here, while you worked here, and whether you stayed or considered leaving, including “What was your motivation for working here at this location? What are your career expectations and how have they changed? What are the support mechanisms here? How has your family influenced your decisions? How does your background influence your decisions? How does your patient population affect your decision to work here? What advice and recommendations do you have for recruiting more doctors to underserved areas?”

Personal Motivators

Personal motivators attracted participants to certain practice settings and indicate how intrinsic factors met individual interests, such as working in specific roles or patient settings. The most frequently mentioned subtheme was the opportunity for personal growth, mentioned 166 times, followed by self-identity (143 times) and mission-based values (83 times).

Personal growth opportunities.

Opportunities to extend job responsibilities, develop new skills, and augment one's career as a factor in physician career decisions presented as the most salient subtheme. A White family physician in a nonunderserved area mentioned, “I was ready to make a change; so this offered research and also something different.”

Self-identity.

Some physicians cited their self-identity, such as their language, personal, family, cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic backgrounds, as a driving force for decision making. “My patients remind me of my cousins and my aunts and my uncles,” said a Latino family physician.

Mission-based values.

Physicians described a sense of responsibility or commitment to a particular community, a defined patient population, or a moral obligation. For example, a White pediatrician practicing in an underserved area put it this way, “You have to find people that are dedicated to serve this community.”

Career Motivation

Career motivators focused on career satisfaction, work hours, loan repayment, and geography. The most common subtheme described was salary and benefits (mentioned 166 times), followed by work hours and lifestyle (131), career satisfaction (102), family (86), geography (73), and loan repayment programs (52).

Salary and benefits.

Participants described salary, health benefits, retirement funds, and educational support as important career motivators, particularly if participants had greater educational debt. An African American physician complained that by working in an underserved area, he was doing “double work for less money.”

Work hours and lifestyle.

Participants described work's effect on time spent with family, pursuing hobbies, and making other lifestyle choices as an important reason for choosing a practice location by the majority of physicians. As 1 Latino internist stated simply, “No weekends, no pager.”

Career satisfaction.

This category included descriptions of greater continuity of care, patient care, enriching experience, and emotional satisfaction, as well as low career satisfaction from boredom, burnout, and lack of stability. A Latino internist in a nonunderserved setting admitted, “I think the practice, the way I'm running it, really limits [burnout]. It allows me time to control my schedule.”

Family.

Many physicians described the importance of family (i.e., spouse, children, and extended family) as an important career motivator and specifically cited life events, such as having a baby, marriage, and divorce, that influenced career choices. A Latino family physician in an underserved area said, “I didn't want to leave because it was where my family was.”

Geography.

The physicians often described the geographic location of their practice as important, mentioning particularly the length of the commute and the desirability of living close to work. A Latino family physician in a nonunderserved area explained, “The location—it's only about 4 or 5 miles from my house.”

Loan repayment programs.

Twenty-one percent of the physicians had some type of loan repayment program or service obligation, such as the National Health Service Corps, Public Health Service, or military service, which influenced their decision to practice in underserved settings.

Clinic Support

Clinic support factors included work environment (mentioned 135 times), provider team (111), reimbursement (92), and information technology (48).

Work environment.

One strong motivator for the majority of physicians was being in a positive work environment, described as working with others who were part of the team and valued high-quality work. A White pediatrician in a nonunderserved area stressed, “When someone is working 8 or 10 hours a day in an environment, one needs to make it as soothing, as comforting, and as warm and friendly as possible.”

Provider team.

Provider team was a subtheme describing a cohort of individuals that included specialists, mental health providers, social service providers, and ancillary service providers. An African American physician emphasized, “But it's really more of … colleagues that keep me here.”

Reimbursement.

Financial remuneration and payment streams were linked to physicians’ time and energy spent on billing and insurance reimbursement mechanisms.

Information technology.

Information technology included descriptions of having electronic charting, laboratory orders, and results. An African American family physician in a nonunderserved setting shared his vision,

Not to mention electronic medical records is no longer the wave of the future; it's the wave of now… . I saw a patient even today who had 2 appointments this morning… . The person that she saw … already chart closed. I saw everything.

Differences in Themes by Chosen Practice Area and by Race/Ethnicity

Physicians who worked in underserved areas were significantly more likely to emphasize mission-based values (P < .001) and self-identity (P = .02) as reasons for choosing their practice location (Table 3). By contrast, physicians who practiced in nonunderserved areas were significantly more likely than were those in underserved areas to emphasize work hours and lifestyle as the main reasons for choosing their practice location (P = .05). Physicians ranked other themes similarly in both practice settings.

TABLE 3.

Factors That Influence Practice Location: Ranking for “How did you decide to work here?” Among Underserved and Nonunderserved Physician by Practice Location and Race/Ethnicity: Los Angeles County, CA, 2008

| Theme | Underserved, Rank (Frequency) | Nonunderserved, Rank (Frequency) | White, Rank (Frequency) | African American, Rank (Frequency) | Latino, Rank (Frequency) | Overall, No. (% of Participants) |

| Mission-based values*** | 1 (16) | 8 (2) | 3 (4) | 1 (14) | 2 (7) | 18 (43) |

| Personal growth | 2 (13) | 1 (12) | 1 (14) | 2 (7) | 3 (7) | 25 (60) |

| Self-identity** | 3 (10) | 9 (2) | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 5 (6) | 12 (29) |

| Geography | 4 (8) | 2 (9) | 2 (5) | 3 (4) | 1 (8) | 17 (40) |

| Family | 5 (7) | 4 (6) | 5 (4) | 7 (3) | 5 (6) | 13 (31) |

| Work environment | 6 (5) | 3 (8) | 4 (4) | 6 (3) | 3 (6) | 13 (31) |

| Loan repayment programs | 7 (3) | 10 (1) | 8 (1) | 10 (1) | 8 (2) | 4 (10) |

| Career satisfaction | 8 (1) | 6 (5) | 7 (2) | 5 (3) | 10 (1) | 6 (14) |

| Salary and benefits | 9 (1) | 7 (3) | … | 9 (2) | 9 (2) | 4 (10) |

| Work hours and lifestyle* | 10 (1) | 5 (6) | … | 4 (4) | 7 (3) | 7 (17) |

| Provider team | 11 (0) | 11 (1) | … | 11 (1) | … | 1 (2) |

Note. We used the Fisher exact test to test for group differences between theme frequencies for underserved and nonunderserved groups. Ellipses indicate theme not mentioned when asked, “How did you decide to work here?”

*P = .05; **P = .02; ***P < .001.

There were no differences among African American, Latino, and White physicians in the top 3 reasons for choosing their practice location: mission-based values, personal growth, and geography. Compared with non-Latino Whites, African American physicians described a greater breadth of reasons for choosing a position. Both African Americans and Latinos gave higher rank to salary and benefits and work hours and lifestyle as reasons for choosing their current position.

Identifying Retention and Recruitment Strategies by Themes

From the themes and participant training characteristics, we developed a conceptual framework to illustrate how and why physicians practice in their current settings (Figure 1). We examined the pathways of physicians who had left underserved areas and those who considered leaving and quantified the number of participants in each stage, noted by the individual counts. Physicians noted that they worked in underserved areas because of mission-driven values, self-identity, and work hours and lifestyle. Among the physicians who left, at least 1 physician listed each of the following reasons: work hours and lifestyle, practice location, higher salary, career progression, and work environment. Of all 42 physicians, 10 both trained and worked in a nonunderserved area. Of the 32 physicians who trained or were from an underserved area, 26 physicians (81%) worked in an underserved setting. At the time of the interview, 21 physicians (50%) worked in underserved settings, and 5 (24%) had left an underserved setting to work in nonunderserved settings. No physicians who trained in a nonunderserved setting went to work in an underserved setting.

FIGURE 1.

Pathways to increasing physician supply in underserved areas: Los Angeles County, California, 2008.

Note. The diagram shows the pathways of physicians into and out of underserved practice locations using physicians’ descriptions of residency training location (underserved vs nonunderserved setting); childhood background (description of being from an underserved area or nonunderserved area); and positions held since residency (underserved vs nonunderserved).

Among the 5 physicians who left practices in underserved communities, the most salient subtheme mentioned for leaving the underserved area concerned work hours and lifestyle (3 of 5 physicians). Other reasons for leaving mentioned by at least 1 physician were salary and benefits, geography, clinic support, and provider team. Among the 5 physicians practicing in underserved areas who had seriously considered leaving, the most salient subthemes mentioned were work hours and lifestyle and geography (3 of 5 physicians). At least 1 physician also considered leaving because of 1 of the following reasons: salary and benefits, personal growth, career satisfaction, and environment. The experiences of the physicians in our sample suggest that residents who train in a nonunderserved community are unlikely to practice in underserved settings. By contrast, physicians who complete residency training in underserved areas are more likely to work in underserved settings.

DISCUSSION

This exploratory study of a diverse group of physicians from Los Angeles County provides important insights into the roles of how personal background, altruism, individual values, and lifestyle factors influence career choices. The physicians we interviewed who practiced in underserved areas were more likely to report mission-based values (i.e., a sense of responsibility or moral obligation to a particular community or a defined patient population) and self-identity (including race, language, and personal or family background) as motivators. We also found that work hours and lifestyle were important for all physicians but that these factors appeared to play a particularly important role for physicians who had left or considered leaving an underserved area. Regardless of their race or ethnicity, the majority of physicians who practiced in underserved areas reported feeling a unique connection to the particular community in which they practiced. Our finding that none of the physicians who trained in a nonunderserved setting went to work in an underserved setting underscores the importance of training in underserved locations as a predictor of long-term practice in such settings.

This study makes several contributions to the literature on physician practice choices. Through intensive interviews, we were able to obtain more details on reasons for selecting or staying in a practice location than were obtained in previous studies, which have generally relied on surveys or administrative data. This approach allowed us to explore complex personal factors beyond race and socioeconomic background that influenced physicians’ decisions to work in underserved areas. The approach also provided insight into tradeoffs between lifestyle factors and mission-based values that some physicians sometimes make: lifestyle was a very large factor for some physicians, but for others lifestyle was secondary to mission-based values. We shared these themes with the CAB members as a potential area for future work.

Little research has explored personal factors that motivate physicians to seek out work. Previous research has provided few solutions, beyond increasing physician diversity, that could address shortages in underserved areas. Our study suggests that examining humanistic- and intrinsic-level factors in greater detail earlier in the medical education selection process may be an important strategy for identifying physicians who are motivated to practice in underserved areas. This work also suggests that clinic administrators should consider modified work hours and lifestyle factors to retain a greater number of physicians who possess a strong commitment to serve underserved populations.

Figure 1 shows the many opportunities for improving recruitment and retention of primary care doctors in underserved areas. We recognize that this process begins first with the development of a dynamic recruitment process that both assesses academic achievement and explores deeper student commitment to working with underserved populations. Next, residency opportunities must exist in diverse and underserved settings that model future practice opportunities in underserved settings. Finally, workplace settings must develop retention policies that incorporate modified work hours and lifestyle considerations to complement a competitive salary and benefits package.

Limitations

These analyses have some limitations. Semistructured interviews are useful in identifying major themes but are sensitive to the interpretations of researchers. We used several strategies to reduce potential bias. First, members of the study team with different areas of expertise independently reviewed transcripts. We also used standard qualitative methods, including pile-sorting and multiple investigator review, to develop the primary themes. Another potential limitation is that we recruited our physician participants through referrals from the CAB and a subsequent snowball sampling process. Thus, the experiences and opinions described in the transcripts may not be representative of physicians from other areas. Fisher's exact test may not be appropriate for a nonrandom sample frame. In addition, findings from a state such as California, which has a higher proportion of physicians in staff model health maintenance organizations than the national average, may not be generalizable to other states. Our finding of the importance of work hours and lifestyle factors may reflect the higher number of physicians in a staff model health maintenance organization, but we saw no difference in responses between physicians in this setting and those in academic or private settings. However, our findings generate multiple hypotheses for future exploration and lay the groundwork for more nationally representative analyses to identify a broader array of strategies for improving physician supply in underserved areas.

Much of the recent activity in workforce policy has focused on increasing medical student slots in the hope that some of these doctors will focus on undeserved areas.28 However, simply increasing the number of physicians does not address other important deficiencies, such as specialty distribution or physician recruitment strategies to benefit underserved areas. Selecting mission-driven medical students from underserved areas and encouraging them throughout their training to pursue residency training and professional opportunities in underserved settings would efficiently increase the number of physicians in underserved areas. Further research is needed to characterize humanistic- and intrinsic-level factors among premedical students that are linked to eventual practice in underserved areas.

To address the health care needs of vulnerable and minority populations, we need both policies that support a larger primary care workforce and incentives that encourage physicians to practice in shortage areas. In addition, more opportunities are needed to educate medical students from underserved, minority, and immigrant populations, since individuals with these backgrounds may be among the most mission-based physicians.17,18 As fewer medical students choose primary care specialties, we must also examine how best to support primary care physicians who practice in underserved areas to retain them in those communities.7,29 Scholarship and loan repayment opportunities have been effective, but primary care payment reform may be another important mechanism for sustaining long-term practice commitments30 as educational debt loads rise.

Conclusions

Ultimately, a concerted health care workforce policy can address distribution disparities in underserved areas and can comprehensively address such challenging issues as benefits, salary, lifestyle, work schedule, and physician specialty distribution. By using enlightened and informed recruitment strategies that seek out and develop a corps of motivated, mission-driven, and committed primary care physicians and retaining them by employing strategies to improve work–life balance, we can meet the challenge of disparities in care among the underserved. The current health care reform debate provides unique opportunities to develop and implement such strategies.

Acknowledgments

K. Odom Walker received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program at UCLA and the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly under National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (grant P30AG021684). A. Brown received support from the Beeson Career Development Award (K23 AG26748), the UCLA Resource Center in Minority Aging Research (grant AG02004), and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant P20MD00148).

We would like to acknowledge our CAB members, including Charles Drew University, Community Clinic Association of Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, and Healthy African American Families, Los Angeles County Medical Association, Latino Medical Policy Institute, and Region VI of the National Medical Association. We would also like to thank Trudy Singzon, MD, MPH, and Sharon L. Hayes for their assistance with data collection and preparation.

Human Participant Protection

We obtained approval from the RAND institutional review board, Santa Monica, CA.

References

- 1.Basu J, Clancy C. Racial disparity, primary care, and specialty referral. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 Pt 2):64–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Probst JC. More may be better: evidence of a negative relationship between physician supply and hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(4):1148–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeAngelis CD. Commitment to care for the community. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1929–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pear R. Shortage of doctors an obstacle to Obama goals. New York Times. April 27, 2009:A1 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal D. New steam from an old cauldron—the physician-supply debate. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1780–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper RA, Getzen TE, McKee HJ, et al. Economic and demographic trends signal an impending physician shortage. Health Aff. 2002;21(1):140–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper RA. It's time to address the problem of physician shortages: graduate medical education is the key. Ann Surg. 2007;246(4):527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitcomb ME. Physician supply revisited. Acad Med. 2007;82(9):825–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Smedley BD, Stith AY, et al. Unequal Treatment. Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the US Healthcare Workforce. In the Nation's Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Nation's Healthcare Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, et al. Primary care physicians who treat Blacks and Whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brotherton SE, Stoddard JJ, Tang SS. Minority and nonminority pediatricians’ care of minority and poor children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(9):912–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of Black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care to underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen JA, Conaway MR, Bailey BA, et al. Predicting rural practice using different definitions to classify medical school applicants as having a rural upbringing. J Rural Health. 2007;23(2):133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabinowitz H, Diamond J, Markham F, et al. A program to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas: impact after 22 years. JAMA. 1999;281(3):255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Veloski JJ, et al. The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians’ care of underserved populations. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1225–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman JS, Campbell EG, Gokhale M, et al. Residents’ preferences and preparation for caring for underserved populations. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):535–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko M, Heslin KC, Edelstein RA, et al. The role of medical education in reducing health care disparities: the first ten years of the UCLA/Drew Medical Education Program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):625–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko M, Edelstein RA, Heslin KC, et al. Impact of the University of California, Los Angeles/Charles R: Drew University Medical Education Program on medical students’ intentions to practice in underserved areas. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):803–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabinowitz HK. Recruitment, retention, and follow-up of graduates of a program to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(13):934–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porterfield DS, Konrad TR, Porter CQ, et al. Caring for the underserved: current practice of alumni of the National Health Service Corps. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2003;14(2):256–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman J, Ferrer RL, Greiner KA. Viewpoint: developing a physician workforce for America's disadvantaged. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, Hall B. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services Shortage Designation: HPSA, MUAs, and MUPs. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage. Accessed November 30, 2009

- 26.Trost JE. Statistically nonrepresentative stratified sampling: a sampling technique for qualitative studies. Qual Sociol. 1986;9(1):54–57 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper RA. Scarce physicians encounter scarce foundations: a call for action. Health Aff. 2004;23(6):243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich EC, Liebow M, Srinivasan M, et al. Medicare financing of graduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(4):283–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron RJ. The chasm between intention and achievement in primary care. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1922–1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]