In their article on HIV/AIDS mortality, Rubin et al. approvingly cite Braveman's definition of a health inequality as “a difference in which disadvantaged social groups … systematically experience worse health or greater health risks than more advantaged social groups.”1(p1053) Later in her work, Braveman discusses two common effect measures used when comparing two groups, the rate ratio and the rate difference, and observes that “both absolute and relative differences can be meaningful.”2(p178) She also recommends that any systematic approach to studying health inequalities should calculate both rate ratios and rate differences, and examine how they change over time.

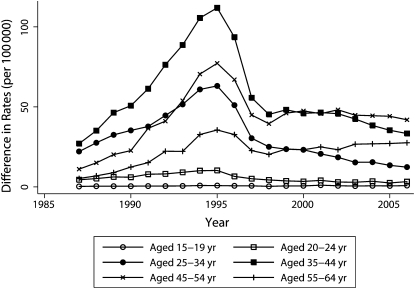

Rubin et al. only partially followed Braveman's recommendations in their research, concluding that the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) led to “significant exacerbations of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality by both SES [socioeconomic status] and race.”1(p1057) Although this is true for the rate ratios, as Figure 1 demonstrates, the introduction of HAART reduced absolute mortality inequalities by race, particularly among those aged 25 to 54 years, the group with the highest pre-HAART mortality. One can observe similar reductions in absolute inequalities by SES.

FIGURE 1.

Black–White rate difference in HIV/AIDS mortality: United States, 1987–2005.

While Rubin et al. note that socioeconomic and racial rate differences decreased during this time period, they argue that

we are concerned about relative rates, which grew much larger between the pre- and post-HAART periods … because we think policy and practice should address inequalities by ensuring everyone benefits equally from treatments like HAART.1(p1057)

This contention is supportable only if one already defines inequality exclusively in relative terms. If inequality is defined in absolute terms, then the introduction of HAART had a greater beneficial impact on Blacks and the socioeconomically disadvantaged. Although there has been some debate on the matter,3,4 there is no definitive epidemiologic or statistical reason to prefer one measure to another, nor do Rubin et al. attempt to provide one.5

Rubin et al. also conclude that

if similar patterns are replicated for other lifesaving discoveries, the cumulative effect of the maldistribution of such benefits will leave our society with enduring, perhaps even growing, health inequalities.1(p1057)

Again, this contention is supportable only if one looks at relative inequality alone. By contrast, one might conclude that the introduction of HAART led to a net gain in terms of social justice, reducing mortality among all groups, harming none, reducing the number of excess deaths among Blacks and low-SES groups, and reducing absolute inequalities. To be sure, unacceptable levels of inequality are still present, but only in an exclusively relative sense have they “grown.”

We agree with Rubin et al.'s recommendation that public health policies strive for an equitable distribution of resources, but we disagree with the assertion that HAART has unambiguously increased inequalities. This interpretation requires strict allegiance to the relative comparison without any attention to the actual number of lives saved or lost. As such, it is at best only half of the story. Like Braveman, we recommend that health inequalities researchers strive for transparency by presenting their data in both absolute and relative terms and by explicitly stating the philosophical or political values that underlie their preference for one or another.5 Doing so will make for a clearer and more complete representation of the data, and therefore better health policy.

References

- 1.Rubin MS, Colen CG, Link BG. Examination of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States from a fundamental cause perspective. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1053–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):167–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Low A, Low A. Importance of relative measures in policy on health inequalities. BMJ. 2006;332(7547):967–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet. 2000;356(9235):1093–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper S, King NB, Meersman SC, Reichman ME, Breen N, Lynch J. Implicit value judgments in the measurement of health inequalities. Milbank Q. 2010;88(1);4–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]