Abstract

Objectives. We estimated the use of preventive dental care services by the US Medicare population, and we assessed whether money spent on preventive dental care resulted in less money being spent on expensive nonpreventive procedures.

Methods. We used data from the 2002 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey to estimate a multinomial logistic model to analyze the influence of predisposing, enabling, and need variables in identifying those beneficiaries who used preventive dental care, only nonpreventive dental care, or no dental care in a multiple-variable context. We used regression models with similar controls to estimate the influence of preventive care on the utilization and cost of nonpreventive dental care and all dental care.

Results. Our analyses showed that beneficiaries who used preventive dental care had more dental visits but fewer visits for expensive nonpreventive procedures and lower dental expenses than beneficiaries who saw the dentist only for treatment of oral problems.

Conclusions. Adding dental coverage for preventive care to Medicare could pay off in terms of both improving the oral health of the elderly population and limiting the costs of expensive nonpreventive dental care for the dentate beneficiary population.

For many retirees, paying for dental care treatment can be difficult.1–3 According to the 2006 Health and Retirement Study, out-of-pocket dental expenditures over the previous 2-year period for persons aged 51 years and older averaged $776 for those with insurance coverage and $1126 for those without insurance coverage, among those with a dental visit during that period.4 These amounts are not trivial, especially for those who live on a fixed income. Seventy percent of persons aged 65 years and older in 2004 were not covered by any dental insurance.5 Without assistance, older Americans who are poorer may choose to delay or forgo dental care, but postponing dental care may lead to expensive complications.6,7 As recently reported in the New York Times, “Left unchecked, a small cavity that would cost about $100 to fill can easily turn into a $1000 root canal. Skip those $80 cleanings each year, and you may be looking at $2000 worth of gum disease.”8

Studies of the impact of preventive dental care visits have primarily focused on younger populations.9–11 Insufficient attention has been paid to the possibility that preventive dental care may limit expensive nonpreventive dental care procedures among an older population. Previous research on preventive dental care has either not focused strictly on the elderly12 or has not used nationally representative data.13

To fill these gaps in the literature, we sought to identify the characteristics of older adults who used preventive and nonpreventive dental care as well as those who used no dental care at all. Previous studies have found patterns of increasing dental care use over the life span,14 as well as differences in racial/ethnic background, education, and income levels in the use of dental care among elderly populations.15,16 Data from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey show similar differences in the use of preventive services over the entire community-based population.17

We then assessed dental care use and costs for beneficiaries who received preventive care during the year, and we compared those figures with dental care use and costs for those who did not receive preventive care to determine whether investing in preventive care can affect costs related to more expensive nonpreventive procedures.

METHODS

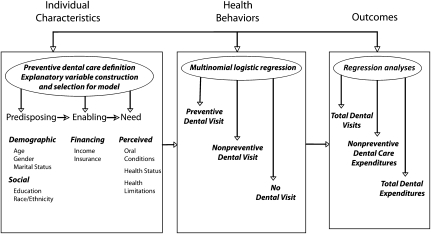

The Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) is a continuous, multipurpose survey of a nationally representative sample of aged, disabled, and institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries.18 MCBS, which is sponsored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, is the only comprehensive source of information on the health status, health care use, health insurance coverage, and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the entire spectrum of Medicare beneficiaries.18 MCBS-sampled persons are interviewed 3 times a year over a 4-year period to form a continuous profile of their health care experiences. Interviews are conducted regardless of whether the respondent resides at home or in a long-term care facility but do use the version of the questionnaire appropriate to the respondent's setting.18 For the current study, we excluded beneficiaries who resided in long-term care facilities during the entire survey year. We included beneficiaries who were in the community-dwelling population for the entire survey year, in addition to beneficiaries who were in the community population for part of the year, although we excluded data for the portion of the year when they were in a long-term care facility. The model and analytic decision-making process for this study are summarized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Behavioral model of dental services use and analytic framework for determining cost impact of preventive dental care.

Note. Boldface and italicized text represents primary characteristics, factors, and analyses used in this adaptation of the Andersen and Davidson model.

Source. Adapted from Andersen and Davidson.7

Definition of Preventive Dental Care

The rationale for separating beneficiaries with dental use into those with preventive care and those without preventive care is that elective, preventive services are a better proxy for placing a high priority on good oral health than are nonelective services (such as fillings, crowns, and root canals). Beneficiaries who do not obtain at least 1 cleaning during the year but appear in the dentist's office for a diagnostic procedure (e.g., examination or x-ray), are most likely there for a nonelective procedure. Such nonelective users may differ from dental users seeking elective, preventive services because they place a lower priority on oral health care and may also have better access to dental care than nonusers of any dental care.19

Similar to Swank, Vernon, and Lairson,12 we defined preventive dental care as having at least 1 dental visit during the survey year (2002) involving a cleaning. We considered more restrictive definitions including exams, X-rays, or at least 2 cleanings during the year; but the most restrictive of these definitions reduced the sample of those with preventive dental care by nearly 60% and produced a nearly 4-fold increase in the sample of those with dental care use but without any preventive care. Statistical comparisons using z tests across the wide range of beneficiary attributes discussed below found that (1) the characteristics of those using preventive dental care did not differ markedly across alternative definitions of preventive care, and (2) the beneficiary group with dental use but without any cleanings was distinctly different from those with at least 1 cleaning and from those without any dental care. Data on the type of service received at a dental visit were collected in question DU7 in the 2002 MCBS dental utilization and event questionnaire.20

Construction of Explanatory Variables

We began with a core group of beneficiary characteristics from the MCBS by working within Andersen's conceptual framework.7 These core characteristics were self-reported data on predisposing factors for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, household size, and community status (full year vs part year); an enabling factor for income; and a need factor for health status. Additional need and predisposing factors were constructed for smoking behavior; self-reported difficulty eating solid food because of teeth problems; health conditions ever diagnosed by a physician; and limitations in specific activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental ADLs (IADLs), and physical functioning. An enabling variable was constructed to measure dental insurance coverage, but only for beneficiaries who saw a dentist during the year.

Model Testing

Preliminary model testing for the likelihood of using preventive dental care with the core set of explanatory variables described above confirmed the addition of variables for smoking behavior and self-reported difficulty eating solid food because of teeth problems to the core model. We did not include the dental coverage variable among the explanatory variables in the model because of its high correlation with dental care utilization. Correlation within and across the 4 sets of general health care status categories for difficulties with ADLs, IADLs, physical limitations, and medical conditions necessitated additional model testing to determine which among the 4 measures provided the largest contribution to the model's explanatory power. To reduce the correlation within each group of health limitation variables, we constructed dummy variables for the number of conditions or limitations within each group. On the basis of our preliminary testing, we selected the number of physical function limitations for the multinomial logistic model.

Model Estimation

We then estimated a multinomial logistic model to analyze the influence of predisposing, enabling, and need variables in identifying those using preventive dental care, those using only nonpreventive dental care, or those using no dental care. A Wald test for combining alternatives in Stata21 confirmed the split of the sample into 3288 beneficiaries using preventive care, 1265 using only nonpreventive care, and 6029 not using dental services. Finally, we estimated the impact of preventive dental care in regression models of total and nonpreventive dental care use and expenditure. In computing all estimates and statistics reported, we used the software packages Stata (version 7, StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SUDAAN (version 6.4, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) to take into account the complex sampling design of the MCBS.21,22

RESULTS

There were 10 582 total participants in the 2002 MCBS, representing 33 725 756 Medicare beneficiaries in the community-based population. Among those surveyed, more than half of the unweighted participants were female (55%; n = 5847). Ten percent (n = 1080) of the participants were non-Hispanic Blacks, and 7% (n = 792) were Hispanic. About half (n = 5275) of the participants were aged 75 years or older, 15% (n = 1621) were aged 64 years or younger, and 35% (n = 3686) were aged 65 to 74 years. Seven percent (n = 755) were part-year community dwellers.

Characteristics of Sample Population

Beneficiaries who used preventive dental care.

Table 1 shows the sample means of selected variables by type of dental care use. Users of preventive dental care were generally more likely than the other 2 beneficiary groups to be aged 65 to 79 years and generally less likely to be aged younger than 65 years or older than 80 years. Compared to the other 2 groups, users of preventive dental care were better educated; had higher incomes; were more likely to be nonsmokers, White, non-Hispanic, and married; and were more likely to have very good or excellent health, no teeth problems, and fewer health conditions and limitations. Compared with beneficiaries who used only nonpreventive dental care, preventive care users were more likely to have dental insurance coverage, and they visited the dentist more often during the year (2.83 vs 2.49 visits), but they visited less often for more expensive nonpreventive procedures (0.83 vs 1.58 visits). As a result, preventive care users paid less in total ($560 vs $822, on average) and out-of-pocket ($408 vs $623) expenses for their total dental care and less in total ($263 vs $581) and out-of-pocket ($189 vs $433) expenses for nonpreventive dental care than did users of nonpreventive care only.

TABLE 1.

Means of Selected Participant Variables, by Use of Dental Care: Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), 2002

| Variables | All Beneficiaries | Population Receiving Preventive Dental Care | Population Receiving Only Nonpreventive Dental Care | Population Receiving No Dental Care |

| Number of beneficiariesa | 33 725 756 | 10 948 187 | 4 053 975 | 18 723 595 |

| Age, y, % | ||||

| < 65 | 12.48 | 8.15y | 15.96 | 14.25 |

| 65–69 | 16.68 | 18.50x | 15.97 | 15.77 |

| 70–74 | 24.29 | 27.35y | 24.26 | 22.51 |

| 75–79 | 20.89 | 23.67y | 19.30 | 19.61 |

| ≥ 80 | 25.66 | 22.34x | 24.50x | 27.86 |

| Women, % | 55.71 | 57.10y | 52.61 | 55.57 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9.34 | 2.76y | 8.92x | 13.28 |

| Hispanic | 7.49 | 4.27y | 9.72 | 8.90 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 78.96 | 90.03y | 76.19 | 73.09 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 3.99 | 2.72y | 4.94 | 4.53 |

| Annual personal income, % | ||||

| ≤ $10 000 | 20.16 | 8.36y | 18.85x | 27.35 |

| $10 001–$20 000 | 29.92 | 20.68y | 29.96x | 35.31 |

| $20 001–$35 000 | 32.21 | 38.67y | 33.05x | 28.26 |

| > $35 000 | 17.70 | 32.29y | 18.14x | 9.08 |

| Education, % | ||||

| Some or no high school | 32.08 | 13.61y | 28.35x | 43.68 |

| High school graduate | 50.09 | 54.65x | 52.86x | 46.51 |

| College graduate | 17.64 | 31.60y | 18.54x | 9.28 |

| Marital status, % | ||||

| Married | 52.03 | 61.07y | 54.96x | 46.10 |

| Widowed/divorced | 42.06 | 33.76y | 39.63x | 47.44 |

| Never married | 5.87 | 5.13x | 5.35 | 6.41 |

| Household size, % | ||||

| 1 | 34.89 | 31.65x | 33.01 | 37.20 |

| 2 | 49.90 | 58.37y | 50.56x | 44.81 |

| 3 or more | 15.18 | 9.98x | 16.43 | 17.96 |

| Health status, % | ||||

| Fair/poor | 27.14 | 17.02y | 28.08x | 32.86 |

| Good | 31.35 | 31.00 | 33.91 | 31.01 |

| Excellent/very good | 40.04 | 51.27y | 37.02 | 34.13 |

| Part-year community resident, % | 5.45 | 2.50x | 3.27x | 7.73 |

| Difficulty eating solid foods because of teeth problems, % | 12.19 | 6.15y | 20.10x | 14.01 |

| Smoking status, % | ||||

| Former smoker | 47.51 | 49.96x | 48.43 | 45.82 |

| Current smoker | 13.73 | 7.76y | 13.82x | 17.20 |

| Never smoked | 38.76 | 42.46y | 37.65 | 36.75 |

| Dental insurance coverage, %b | 20.63 | 46.14y | 40.07x | 1.50 |

| Limitations in physical functioning | ||||

| No. of difficulties with ADLsc | 0.70 | 0.45y | 0.74 | 0.84 |

| No. of difficulties with IADLsd | 1.14 | 0.75y | 1.13x | 1.37 |

| No. of conditions ever diagnosed by physiciane | 2.84 | 2.58y | 3.02 | 2.95 |

| No. of physical limitationsf | 2.18 | 1.75y | 2.25x | 2.43 |

| Dental care in past y | ||||

| No. of dental events | 1.22 | 2.83z | 2.49 | 0 |

| No. of dental cleaning events | 0.53 | 1.63 | 0 | 0 |

| No. of dental events not cleaning, exam, or X-rays | 0.46 | 0.83z | 1.58 | 0 |

| Dental costs in past y, $ | ||||

| All dental events | 280.62 | 560.22z | 821.60 | 0 |

| Dental cleaning events | 66.28 | 204.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Dental events not cleaning, exam, or X-rays | 155.12 | 262.61z | 581.25 | 0 |

| Out-of-pocket dental costs in past y, $ | ||||

| All dental events | 207.22 | 407.57z | 623.19 | 0 |

| Dental cleaning events | 47.60 | 146.62 | 0 | 0 |

| Dental events not cleaning, exam, or X-rays | 113.48 | 189.32z | 432.77 | 0 |

Note. ADLs = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living. Sample includes only full-year or part-year community-dwelling beneficiaries.

Includes Medicare beneficiaries with missing values for race/ethnicity, education, marital status, household size, and health status.

Limitations in the survey data limit the ability of the MCBS to estimate dental insurance coverage reliably for Medicare beneficiaries who did not see a dentist during the year.

Activities of daily living are bathing/showering, dressing, eating, getting in/out of bed/chair, walking, and using the toilet.

Instrumental activities of daily living are using the telephone, doing light housework, doing heavy housework, preparing meals, shopping for personal items, and managing money.

The list of conditions is as follows: hardening of the arteries, hypertension/high blood pressure, myocardial infarction/heart attack, angina pectoris/coronary heart disease, other heart conditions, stroke/brain hemorrhage, skin cancer, other (nonskin) cancer, diabetes/high blood sugar, rheumatoid arthritis, mental retardation, osteoporosis/soft bones, broken hip, Parkinson's disease, emphysema/asthma/cardiopulmonary disease, complete/partial paralysis, and lost arm or leg.

Physical limitations are defined as any difficulty with stooping/crouching, kneeling, lifting/carrying 10 pounds, extending arms above shoulders, writing/handling objects, or walking ¼ mile or 2 to 3 blocks.

Indicates that the mean in the column is significantly different from the mean for the population with no dental care (P ≤ .05).

Indicates that the mean in the column is significantly different from the mean for the population with only nonpreventive dental care and the mean for the population with no dental care (P ≤ .05).

Indicates that the mean in the column is significantly different from the mean for the population with only nonpreventive dental care (P ≤ .05).

Beneficiaries who used only nonpreventive dental care.

Beneficiaries who used only nonpreventive dental care differed from those with no dental care by many of the characteristics that distinguished nonpreventive care users from preventive care users. Compared with nonusers, beneficiaries who used only nonpreventive care were less likely to have physical limitations and less likely to be aged 80 years or older, a part-year community dweller, Black, non-Hispanic, a current smoker, or in fair or poor health. Nonpreventive care users were more likely than were nonusers to be married, to have difficulty eating because of teeth problems, to have a high school or college education, and to have a higher income.

Regression Analysis

The multinomial logistic regression results in Table 2 show the estimated odds of community-dwelling beneficiaries being in the preventive dental care group (second column) or in the nonpreventive dental care–only group (fourth column), relative to being in the nonuser group, after control for characteristics distinguishing the 3 groups of beneficiaries. We also performed a second multinomial logistic regression with the same explanatory variables as the first one, but the second regression specified beneficiaries who used only nonpreventive dental care as the base case. This equation provides the estimated odds of being in the preventive dental care group relative to being in the nonpreventive care–only group (third column). These regressions also provided a test for the separation of the sample into 3 groups on the basis of the beneficiary characteristics examined in our study.

TABLE 2.

Odds Ratios Comparing Participant Variables of Interest, by Use of Dental Care: Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), 2002

| Odds Ratio Point Estimatesa |

|||

| Population Characteristics | Preventive Dental Care vs No Dental Care | Preventive Dental Care vs Only Nonpreventive Dental Care | Only Nonpreventive Dental Care vs No Dental Care |

| Intercept | 5.46** | 8.65** | 0.63** |

| Age, y | |||

| < 65 | 1.14 | 0.84 | 1.35* |

| 65–69 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 0.90 |

| 70–74 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.93 |

| 75–79 | 1.18* | 1.20 | 0.98 |

| > 79 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 0.72** | 0.72** | 1.00 |

| Women (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.32** | 0.38** | 0.84 |

| Hispanic | 0.74* | 0.55** | 1.35* |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.62** | 0.63* | 1.00 |

| White, non-Hispanic (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00) |

| Annual personal income | |||

| ≤ $10 000 | 0.19** | 0.40** | 0.46** |

| $10 001–$20 000 | 0.27** | 0.50** | 0.55** |

| $20 001–$35 000 | 0.49** | 0.71** | 0.69** |

| > $35 000 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Education | |||

| Some or no high school | 0.21** | 0.50** | 0.42** |

| High school graduate | 0.49** | 0.74** | 0.66** |

| College graduate (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Marital status | |||

| Widowed/divorced | 0.85 | 1.01 | 0.85 |

| Never married | 1.32* | 1.63* | 0.81 |

| Married (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Household size | |||

| 1 | 1.46** | 1.29 | 1.13 |

| 2 | 1.31** | 1.27 | 1.03 |

| 3 or more (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Difficulty eating solid food because of teeth problems | |||

| Has difficulty | 0.69** | 0.35** | 1.93** |

| Does not have difficulty (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Health status | |||

| Fair/poor | 0.74** | 0.80 | 0.92 |

| Good | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.94 |

| Excellent/very good (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Physical limitations | |||

| 3 or moreb | 0.71** | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| 2 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 1.09 |

| 1 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.05 |

| 0 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smoker | 0.44** | 0.61** | 0.71* |

| Former smoker | 0.86* | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| Never smoker (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Community resident | |||

| Part year | 0.34** | 0.83 | 0.41** |

| Full year (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. The sample, which only includes full-year or part-year community-dwelling beneficiaries, consists of 9760 observations and excludes 822 persons with missing values for any independent variable from the initial analytic sample. Odds ratios are derived by multinomial logistic regression. The base case for the equation in the second and fourth columns is beneficiaries who did not visit the dentist during the year. The base case for the equation in the third column is beneficiaries who had only nonpreventive dental care. Pseudo-R2 = 0.13.

Odds ratio point estimates in second and fourth columns are estimates of (probability of preventive dental visit [or only nonpreventive dental care]/probability of no dental care) for persons with row characteristic divided by (probability of preventive dental visit [or only nonpreventive care]/probability of no dental care) for omitted characteristic from a multinomial logistic equation, with beneficiaries without dental care as the reference group. Estimates in third column are estimates of (probability of preventive dental visit/probability of only nonpreventive dental care) for persons with row characteristic divided by (probability of preventive dental visit/probability of only nonpreventive dental care) for omitted characteristic from a similar multinomial logistic equation, except with beneficiaries with only nonpreventive dental care as the reference group.

Physical limitations are defined as any difficulty with stooping/crouching, kneeling, lifting/carrying 10 pounds, extending arms above shoulders, writing/handling objects, or walking 0.25 miles or 2 to 3 blocks.

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01.

As an example of interpretation of the estimated odds ratios in Table 2, the estimate for men in the second column (0.72) indicates that the odds of a male beneficiary having a preventive dental visit were 72% of the odds of a female beneficiary having a preventive dental visit, after adjusting for other covariates, where the odds are defined as the probability of a preventive dental visit divided by the probability of not having any dental visit during the year. This means that holding other attributes constant, men were about 70% as likely as women to have their teeth cleaned in the dentist's office rather than going without seeing a dentist during the year.

Preventive dental care versus no dental care.

Apart from the gender effect, the second column of Table 1 shows that the odds of using preventive dental care relative to no dental care were lower for minority racial/ethnic groups than for non-Hispanic Whites and lower for groups with less income and education than for groups with more income and education. We also found a lower likelihood of using preventive dental care among beneficiaries with difficulty eating solid food because of teeth problems than among those with no such difficulty. This likelihood suggests that improved oral hygiene, including annual cleanings at a dentist's office, offers protection against oral health problems. Compared with beneficiaries who had no physical limitations, those who had 3 or more physical limitations were less likely to use preventive dental care and were more likely not to visit the dentist during the year for any reason. The same relationships held true for those in excellent or very good health compared with those in fair or poor health; for those who had never smoked compared with those who were current or former smokers; and for full-year community dwellers compared with part-year community dwellers.

Curiously, the odds of using preventive dental care were half again as high for never-married beneficiaries as the odds for married beneficiaries. The relatively strong positive effects of household sizes of 1 and 2 persons, compared with sizes of 3 persons and larger, might be masking marital-status effects because of correlation between these variables.

Preventive dental care versus only nonpreventive care.

In general, the third column of Table 2 shows that the characteristics that distinguish preventive dental care users from nonusers of dental care also distinguish preventive care users from beneficiaries who only go to the dentist for nonpreventive procedures such as crowns, fillings, and root canals. This holds true across racial/ethnic background, income, education, gender, marital status, difficulty eating because of teeth problems, and smoking status. There were no differences between the 2 groups on the basis of age, household size, physical limitations, health status, and part-year community status.

Only nonpreventive dental care versus no dental care.

The last column of Table 2 identifies characteristics that differentiated beneficiaries who went to the dentist only for oral problems from those who did not visit a dentist's office during the year. As one might expect, if a person reported a problem eating because of their teeth, the odds of having an oral problem treated were nearly twice as high as the odds of not going to the dentist. Interestingly, the odds of having an oral problem treated were also higher for beneficiaries aged younger than 65 years than for elderly beneficiaries (aged 80 years or older), and higher for Hispanics than for non-Hispanic Whites. The odds of having an oral problem treated were lower for groups with lower levels of income and education than for groups with higher levels of income and education; lower for current smokers than for those who had never smoked; and lower for part-year community residents than for full-year community residents.

Dental use and expense.

For preventive dental care to be a good investment, preventive care should help beneficiaries avoid or at least minimize costly nonpreventive dental procedures such as inlays, crowns, bridges, extractions, and root canals. The descriptive results in Table 1 show that beneficiaries who used preventive dental care had more dental visits—but fewer visits for expensive nonpreventive procedures and lower dental expenses—than did beneficiaries who only had oral problems treated at the dentist. The findings in Table 3 confirm these results, after controlling for other influences on beneficiaries' dental use and expenditures. Six regression equations were restricted to a sample of beneficiaries using dental care and were estimated in natural logarithm form for the number of events and for total and out-of-pocket expenses for both total and nonpreventive dental events. The key explanatory variable in the equations was a binary variable indicating that the beneficiary had had at least 1 dental visit with a cleaning during the year. Other covariates in the model were the same as in the multinomial logistic models in Table 2, with the exception of an additional variable indicating dental insurance coverage.

TABLE 3.

Estimates of Effects of Preventive Dental Care on Dental Care Use, Dental Care Expenses, and Out-of-Pocket Payments, for Participants With Dental Care Use: Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 2002

| Dental Care Use or Payments | Coefficient for Preventive Dental Care, b (SE) | Sample Size | R2 |

| Total dental events | |||

| Log of number of events | 0.176** (0.026) | 4284 | 0.118 |

| Log of expense | –0.328** (0.052) | 4228 | 0.095 |

| Log of out-of-pocket payments | –0.416** (0.063) | 3906 | 0.051 |

| Nonpreventive dental events | |||

| Log of number of events | –0.060* (0.030) | 2094 | 0.085 |

| Log of expense | –0.250** (0.065) | 2064 | 0.071 |

| Log of out-of-pocket payments | –0.279** (0.083) | 1893 | 0.050 |

Note. The sample only includes full-year or part-year community-dwelling beneficiaries. The reference group for preventive dental care is beneficiaries with only nonpreventive dental care. Other covariates in the equations are: age dummies, male, race/ethnicity categories, income categories, education categories, marital status, household size, difficulty eating solid food because of teeth problems, health status, physical limitation categories, smoking status, dental coverage, and part-year community resident.

*P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01.

Table 3 displays only the coefficient estimates for the preventive dental care variable. The value of Table 3 is that it confirms the cost savings of preventive dental care found in the descriptive results after introducing controls for potentially confounding influences on dental care use and expense. In all cases, the estimates are statistically significant and in the direction that is consistent with the descriptive findings. Such results suggest that Medicare beneficiaries who use preventive dental care have more dental visits but pay less out of pocket and in total for dental care, both overall and for expensive nonpreventive procedures, than do users of nonpreventive care only.

DISCUSSION

We characterized beneficiaries who did use and did not use preventive dental care, and we further identified the characteristics that split the second group between those who received no dental care and those who only saw a dentist to treat oral problems. We also explored whether diagnostic care should be packaged with preventive care, on the grounds that examinations or X-rays could detect oral disease. We found that among the 1265 beneficiaries in the group classified as nonpreventive dental users, there were 733 beneficiaries with at least 1 dental visit during the year with an examination or an X-ray. We relied on the Wald test for comparing alternatives to determine that these 733 beneficiaries should not be grouped with the 3288 beneficiaries in the preventive group nor left as a separate group, but that the 733 should instead be merged with the other 532 beneficiaries in the nonpreventive dental care group.

Our results are consistent with previous studies confirming dental access problems for minority racial/ethnic groups and for persons with lower income and educational levels.15,16 We also found that beneficiaries in worse overall health status, with more physical and health limitations and difficulties with daily activities, were concentrated in the group that did not visit the dentist for any reason. Compounding such access problems are the limited supply of both dentists and public financing for underserved populations.23 Community outreach through the provision of transportation services, clinics, and provider networks targeted toward the elderly may be required to bring missing dental services to nonusers, much like similar programs targeted toward rural communities.24 Notably, those beneficiaries who visited the dentist only for treatment of oral problems displayed fewer attributes that predict access problems, which are typical of the group of nonuser beneficiaries.

For those beneficiaries who used dental care during the year, our results suggest that preventive dental care reduced their dental bills and out-of-pocket payments, primarily because preventive care is associated with fewer expensive nonpreventive dental procedures. Our descriptive analysis shows that if the beneficiary group receiving preventive dental care required the same nonpreventive dental care as those who received only nonpreventive care, preventive care users would have paid $216 more per capita ($2.4 billion more in total) out of their own pockets for their dental bills in 2002. This analysis does not account for the majority of community-dwelling beneficiaries, who did not see a dentist during the year.

Data were not available from the MCBS to identify the general oral health status of the nonuser group or the percentage of nonusers who were missing their teeth (edentulous). Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the nonuser group suggest that the prevalence of edentulous beneficiaries in this group is higher than the national average of about one third of noninstitutionalized adults aged 65 years and older.16,25 Our limited use–driven measure of dental coverage also did not provide a clear indication of how many nonusers lacked insurance coverage, which is a strong correlate with dental use.5,26 We were only able to identify dental coverage if the beneficiary either (1) received third-party payments for dental expenses or (2) reported having a “dental only” private or public insurance plan. Beneficiaries were not asked directly in the MCBS whether they had dental insurance coverage, so the MCBS was unable to measure dental coverage accurately for persons who did not see a dentist during the survey year. Only 6% of those with dental coverage were identified by having a “dental only” plan, and 1.3% of nonusers were identified as being covered by such a plan.

Limitations of our model include potential omission of relevant variables that could bias model coefficients, such as oral health status, dentate status, and provider supply. The potential for selection bias exists in the dental use and expenditure models from the limited dental coverage variable. Future plans to use MCBS longitudinal data to model the effect of preventive dental care should offer more insight into this study's findings.

The dentate portion of the nonuser group may well consider their lack of preventive dental care a good strategy because they have no dental expenses. However, it is unclear how many of them currently have untreated oral problems or will ultimately develop oral problems in the future that will either diminish their quality of life or will eventually require expensive treatments. Douglas et al. found relatively high percentages of untreated coronal decay, root caries, and severe periodontal pocketing among a representative sample of community-dwelling elders aged 70 years and older living in 6 New England states.27 To provide more definitive answers to the questions we explored, longitudinal data should be used to determine whether periodic preventive dental care in the dentist's office pays off in terms of fewer expensive problems and procedures over time. In the meantime, our limited short-term duration study suggests that it does. The policy implication of our study is that, at a minimum, adding coverage for preventive dental care to Medicare could pay off in terms of both improving the oral health of the elderly population and limiting the costs of expensive nonpreventive dental care for the dentate beneficiary population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health (grant 1R03DE016850-01A2, Preventive Dental Care Services and General Health Care).

The authors wish to thank Pat Stewart and Diane McNally of Pharmaceutical Research Computing, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, for their analytical and programming support.

Human Participant Protection

This project has received an exemption from the University of Maryland institutional review board (appendix 4). The Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) is a nationally representative sample of aged, disabled, and institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries and is sponsored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Data from the MCBS are released to the public in 2 annual data file series: the “Access to Care”series and the “Cost and Use” series. Participation is voluntary, and confidentiality is assured. This exemption is consistent with exemption 4: research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens, if these sources are publicly available or if the information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects.

References

- 1.Marcus M, Schoen MH, May S. An alternative method for financing care for the non-institutionalized geriatric patient. Gerodontology. 1984;3(4):219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bomberg TJ, Ernst NS. Improving utilization of dental care services by the elderly. Gerodontics. 1986;2(2):57–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manski RJ, Goodman HS, Reid BC, Macek MD. Dental insurance visits and expenditures among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):759–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manski RJ, Moeller JF, Chen H, et al. Dental care expenditures and retirement. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(2):148–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manski RJ, Brown E. Dental Use, Expenses, Private Dental Coverage, and Changes, 1996 and 2004. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. MEPS chartbook 17 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shay K. Infectious complications of dental and periodontal diseases in the elderly population. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(9):1215–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen RM, Davidson PL. Ethnicity, aging, and oral health outcomes: a conceptual framework. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11(2):203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konrad W. How to manage dental costs, with or without insurance. New York Times. September 5, 2009:B6 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis C, Teeple E, Robertson A, Williams A. Preventive dental care for young, Medicaid-insured children in Washington State. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):e120–e127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis C, Mouradian W, Slayton R. Dental insurance and its impact on preventive dental care visits for US children. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138(3):369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenney GM, McFeeters JR, Yee JY. Preventive dental care and unmet dental needs among low-income children. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(8):1360–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swank ME, Vernon SW, Lairson DR. Patterns of preventive dental behavior. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(2):175–184 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Branch LG, Antczak AA, Stason WB. Toward understanding the use of dental services by the elderly. Spec Care Dentist. 1986;6(1):38–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manski RJ, Moeller JF, Maas WR. Dental services: an analysis of utilization over 20 years. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(5):655–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson PL, Andersen RM. Determinants of dental care utilization for diverse ethnic and age groups. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11(2):254–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vargas CM, Kramarow EA, Yellowitz JA. The Oral Health of Older Americans. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Aging Trends 3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manski RJ, Moeller JF. Use of dental services: an analysis of visits, procedures, and providers, 1996. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(2):167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey overview. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MCBS/. Accessed July 30, 2010

- 19.Dolan TA, Atchison K, Huynh TN. Access to dental care among older adults in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(9):961–974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MCBS main study - round 34, Fall 2002 community component. DU. Dental utilization and events. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MCBS/Downloads/2002_CCQ_du.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2010

- 21.Stata [computer program]. Version 7.0 College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.SUDAAN [computer program]. Version 6.4 Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertz E, O'Neil E. The growing challenge of providing oral health care services to all Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):65–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration Something to smile about: preventive dental care project for Garrett County. : Rural Health Demonstration Projects 1999 to 2002. Rockville, MD: Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2003:57–59 The Outreach Sourcebook; vol 9 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcus SE, Kaste LM, Brown LJ. Prevalence and demographic correlates of tooth loss among the elderly in the United States. Spec Care Dentist. 1994;14(3):123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manski RJ, Macek MD, Moeller JF. Private dental coverage: who has it and how does it influence dental visits and expenditures? J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(11):1551–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douglass CW, Jette AM, Fox CH, et al. Oral health status of the elderly in New England. J Gerontol. 1993;48(2):M39–M46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]