Abstract

The goals of the Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program (CCROPP) are to promote safe places for physical activity, increase access to fresh fruits and vegetables, and support community and youth engagement in local and regional efforts to change nutrition and physical activity environments for obesity prevention. CCROPP has created a community-driven policy and environmental change model for obesity prevention with local and regional elements in low-income, disadvantaged ethnic and rural communities in a climate of poor resources and inadequate infrastructure. Evaluation data collected from 2005–2009 demonstrate that CCROPP has made progress in changing nutrition and physical activity environments by mobilizing community members, engaging and influencing policymakers, and forming organizational partnerships.

KEY FINDINGS

▪ CCROPP took a community-driven policy and environmental change approach to obesity prevention, with local and regional components.

▪ CCROPP community partners and public health departments increased access to healthy food and physical activity opportunities through neighborhood engagement, inclusive partnerships, and local policymaking.

▪ Community resident engagement was the central strategy CCROPP used to change food and physical activity environments.

▪ CCROPP sites informed state-level policy, and disseminated their accomplishments and lessons learned through state and national networks.

CALIFORNIA'S CENTRAL Valley, one of the nation's leading agricultural regions, is also one of the poorest, where overweight and obesity occur alongside hunger, and where food deserts—places where fresh affordable produce can't be found—abound.1 The Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program (CCROPP) involved 8 counties (Fresno, Kings, Kern, Madera, Tulare, Merced, Stanislaus, and San Joaquin) with similar geographic, social, and political characteristics: few dense urban neighborhoods and many isolated small rural towns. The absence of environments that support access to healthy foods and opportunities for physical activity in the Central Valley has led to the emergence of a new type of obesity-prevention initiative that seeks to create environments that create the conditions that support individuals to adopt healthy eating and physical activity patterns.

THE CENTRAL CALIFORNIA REGIONAL OBESITY PREVENTION PROGRAM

Established by The California Endowment in 2006 as a 3-year, $10 million regional initiative (and extended through June 2010), CCROPP was administered by California State University Fresno's Central California Center for Health and Human Services, and was overseen by the Central California Public Health Partnership, a collaborative venture of the public health department directors from eight Central California counties. CCROPP was implemented in each of the sites by a partnership between the local public health department, a community-based organization, and an obesity council. CCROPP's interventions were supported by technical assistance such as intervention development and implementation, resources, training, and peer-to-peer support.

MODEL OF CHANGE

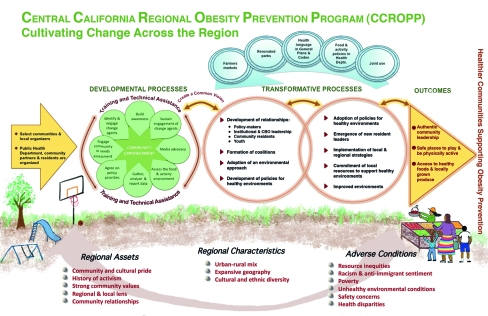

The CCROPP model of change (Figure 1) followed that of Healthy Eating, Active Communities,2 and was developed by integrating ideas and principles from multiple but complementary theoretical frames.3–7 The process included a systematic inquiry into the design and early implementation of CCROPP (M Ruwe et al, unpublished manuscript, October 2009) and an extensive review of literature regarding applications of complex systems theory to social systems3,5 and to obesity prevention.8

FIGURE 1.

Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program (CCROPP) model of change.

EVALUATION

The CCROPP evaluation measures progress on a variety of indicators reflected in local and regional logic models developed by the evaluation team and grantees (Table 1). Examples of CCROPP grantee progress on these indicators appear in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program (CCROPP) Evaluation Methodologies

| Method | Description |

| Logic models | Developed at the local and regional levels to define interventions, expected changes, and evidence of change. The logic models served as a guide for the grantees in implementing their strategies and as a guidepost for the evaluation (8 sites). |

| Public health department environmental assessments | Examined beverage and food sales and physical activity opportunities at health care institutions and public health departments (7 sites). |

| Farmers market and produce stand environmental assessments | Documented beverages and foods for sale at farmers markets and produce stands; in addition, tracked environmental features such as healthy eating signage and EBT and WIC voucher acceptance (7 sites). |

| Physical activity/built environment assessment | Examined the physical activity environment and resources in neighborhoods (6 sites). |

| Community resident focus groups | Documented community residents' perceptions of their social and built environments and their influence on health, and explored factors that engage community residents to advocate for improvements in their community (8 sites; 153 participants). |

| Elected/governmental official stakeholder interview | Documented how local elected and governmental officials are engaged in activities to change community environments to prevent childhood obesity and promote healthy eating and physical activity, including perceptions of policies and resources needed and barriers to changing community environments (8 sites, 35 interviewees). |

| Grantee reporting interviews and profiles | Annual interviews conducted with the site community and public health department leads to discuss progress, accomplishments and challenges; key successes and challenges were then summarized in a grantee profile (8 sites). |

| Community resident survey | Assessed community residents' perceptions of the obesity issue and specific policy strategies as well as government's role in making changes (350 telephone interviews conducted in English and Spanish). |

| Policymaker survey | Assessed policymaker attitudes on the obesity issue as well as strategies to affect environmental and policy change; conducted in the CCROPP counties and in the Healthy Eating Active Communities counties (206 respondents). |

Note. EBT = Electronic Benefits Transfer; WIC = Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

TABLE 2.

Key Preliminary Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program (CCROPP) Evaluation Results, Selected Counties, California, 2006–2009

| Key Preliminary Evaluation Results by Indicators | ||||

| County | Public Health Department Capacity | Community Engagement and Partnerships | Changes to Nutrition and Physical Activity Environments | Policy Change Strategies |

| San Joaquin | Community residents conducted CX3 (Communities of Excellence in Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity Prevention) community health assessments in partnership with public health departments to determine priority interventions; community residents drove setting of priorities | |||

| Stanislaus | Completed a community health assessment | Grassroots community members trained as “block leaders” to become neighborhood organizers | Established farmers market that accepts WIC and EBT vouchers; created Walking School Bus program at 2 elementary schools | Public health department developed a countywide employee worksite wellness policy |

| Merced | Conducted public health department and community meetings on addressing health disparities based on “Unnatural Causes” program | In collaboration with the breastfeeding coalition, developed and implemented breastfeeding- friendly practices at a local hospital; in collaboration with WIC, increased the number of families applying for food stamps | Implemented the acceptance of food stamp EBT at 2 farmers markets; sales of EBT usage increased from $750 in November 2007 to $7500 in March 2008 | Developed and implemented worksite wellness policy at Livingston Medical Group |

| Madera | Continuation of farmers market with multiple partners including the public health department and First 5 Commission; WIC coupons accepted | Youth presented Photovoice and CX3 findings to Madera Vision (City Council, Art Council, school board, chief of police, Parks and Recreation); resident-led Fairmead community council is in the process of becoming a nonprofit organization | School district–wide use of air quality flags; creation of maps of walking trails, biking trails and park spaces in the county; installed equipment at Fairmead toddler park | Community lead was appointed to the general plan committee and ensures that health language is incorporated into the general plan |

| Fresno | New public health department strategic plan objectives aligned with CCROPP goals; public health partner held an Urban Sprawl: What's Health Got To Do With It? forum; developed a built environment and air quality strategic plan with the City and County of Fresno and transportation managers | Created strategic plans with city council and planning departments regarding the built environment and health | Public health department implemented a worksite wellness policy; Burroughs Neighborhood Council worked with city council to secure a covered bus shelter, repaint curbs and crosswalks, and install digital radar speed limit signs at local elementary school | Passage of local farmers market ordinance allowing farmers markets in residential and commercial zoning areas |

| Tulare | Public health department providing health language for city general plan | The public health department's worksite wellness policy was adopted by the Tulare County Health and Human Services Agency; residents advocated for walking, biking, and stroller accessibility for road along Pixley Park | Installed a soccer field and made other structural improvements at local park; school gates at local school left open after hours; established a low-cost fruit and vegetable stand at elementary school | Conducted successful advocacy to prevent closure of and ensure continued funding of the WIC clinic in Earlimart |

| Kings | Passed healthy foods policy at public health department for meetings; walking routes established for public health department staff | The Kettleman City Community Council trained on advocacy and involved in decision making with the Local Assessment Committee | Converted a convenience store into a market to provide more fresh produce | All unincorporated areas now have general plans that include health language |

| Kern | Public health department received a local built environment grant through the California Physical Activity Center to hold roundtable with the planners; senior public health department epidemiologist co-led the Kern County Network of Children GIS taskforce to map factors impacting childhood obesity | Greenfield Walking Group, now a self-sustaining community resident group, advocated for creation of a new walking path at Stiern Park; public health department provided technical assistance to other public health departments and hospitals interested in establishing farmers markets | Breastfeeding policy passed and implemented at the public health department; WIC fruit and vegetable coupon redemption rate at farmers market increased by 25% | Public health department developing health language for city general plan |

Note. EBT = Electronic Benefits Transfer; GIS = geographic information system; WIC = Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

REGIONAL APPROACH

The regional approach united the CCROPP communities and created a forum where strategies and lessons learned can be shares and disseminated widely. The local and regional features of the CCROPP model worked together to accelerate change at both levels. Although the region shared an identity, variation across communities required the ongoing identification and pursuit of shared interests and opportunities. Jurisdictional and administrative barriers may have restricted regional level strategies and prevented policy change. CCROPP provides a model and impetus for overcoming these limitations through the interconnectivity of the grantees' experiences.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND PARTNERSHIPS

Community engagement has been a central element to the CCROPP initiative.9 CCROPP grantees engaged community residents and youth in conducting community nutrition and physical activity environmental assessments, in determining priorities for action, and in acting as advocates for community improvement (Table 2). However, the absence of community infrastructure and resources, presence of language barriers, and fears of immigration status were a few of the challenges faced by Central Valley community residents as they advocated for healthier communities.

Each CCROPP site was engaged in building partnerships with city planners, law enforcement, local businesses, hospitals and clinics, schools, policymakers, and other partners. Through these partnerships, parks were renovated, joint use agreements were adopted with schools, and health language was incorporated into the general plans adopted by cities and counties to guide growth, land development, and zoning.

Chief of Pediatrics Robert Savio of Highland General Hospital spearheaded a campaign to transform the food environment at this public hospital, including subsidizing free or reduced-price produce boxes from West Oakland's Peoples Grocery for low-income patients' families, through a partnership developed by the Healthy Eating, Active Communities program. Photo by Tim Wagner for Partnership for Public's Health. Available at http://www.twagnerimages.com. Printed with permission.

PUBLIC HEALTH DEPARTMENT CAPACITY

The CCROPP public health departments engaged staff in healthy eating and physical activity and adoption of worksite wellness policies, including nutrition standards for foods and beverages, physical activity standards, and breastfeeding policies. The departments conducted trainings on health disparities for staff. Other examples of changes in public health department capacity for improving nutrition and physical activity environments included aligning each public health department's strategic plan objectives with CCROPP's goals, working closely with community partners on establishing farmers markets and introducing health language into general plans. (Table 2)

CHANGES TO NUTRITION AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY ENVIRONMENTS

CCROPP's interventions to change nutrition environments led to the establishment of new farmers markets and produce stands, increased collaboration between communities, schools, public health departments, and farmers and vendors, and increased WIC (Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) coupon redemption and Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) for food stamps in some farmers markets.10

Physical Activity Environments and Built Environments

CCROPP grantees worked to improve access to physical activity (Table 2). Although each CCROPP site pursued different physical activity and built environment changes, a shared goal was increasing pedestrian safety and decreasing crime by partnering with community residents, neighborhood groups, planners, policymakers, and police officers. For example, the Greenfield Walking Group (Kern County), now a self-sustaining community resident group, worked with planners and local elected officials to install a new walking path at a park.

POLICY CHANGE

The CCROPP grantees and community residents engaged school board members, superintendents, planning directors, mayors, and county supervisors in changing policy to support healthy eating and physical activity. Examples include incorporation of health language into general plans and passage of ordinances allowing farmers markets (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The CCROPP experience demonstrates that it is possible to change nutrition and physical activity environments in historically disadvantaged and under-resourced communities. The local obesity prevention strategies of this initiative informed the regional strategies; in turn, the regional framework contributed to the strengthening of local efforts, and provided a trajectory for statewide policy advocacy.

Although the CCROPP grantees have made progress in implementing their interventions and changing nutrition and physical activity environments, more time is required to achieve measurable outcomes. It will be important to continue to evaluate the impact of policy change on Central California environments and the health of community residents.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was funded by The California Endowment to Samuels & Associates for the evaluation of The Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program (CCROPP). The CCROPP evaluation is being conducted with the assistance of the Central Valley Health Policy Institute, Field Research Corporation, and Abundantia Consulting.

The authors wish to thank Ellen Braff-Guajardo, JD, former Program Officer, The California Endowment, and Genoveva Islas-Hooker, MPH, Regional Program Coordinator, Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program, for their contributions to the conceptualization of this research.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was obtained for the community resident focus groups from the California State University Fresno institutional review board. Approval was not sought for the other methodologies because participation in the research did not put participants at risk for harm. All responses were kept confidential.

References

- 1.Bengiamin M, Capitman JA, Chang X. Healthy People 2010. A 2007 Profile Of Health Status. : The San Joaquin Valley: Central Valley Health Policy Institute. Fresno: California State University; 2008. Available at: http://www.csufresno.edu/ccchhs/institutes_programs/CVHPI/publications/_CSUF_HealthyPeople2010_A2007Profile.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samuels S, Craypo L, Boyle M, et al. The California Endowment's Healthy Eating Active Communities (HEAC) program: a midpoint review. Am J Public Health. 2010:100(11):2114–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Yam Y. Unifying Principles in Complex Systems. Cambridge, MA: New England Complex Systems Institute; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Checkland PB. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Checkland P. Soft systems methodology: a thirty year retrospective. Syst Res Behav Sci. 2000;17(1):S11–S58 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weick KE, Quinn RE. Organizational change and development. Annu Rev Psychol. 1999;50:361–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeler D. A Theory of Social Change and Implications for Practice, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation: Community Development Resource Association. Cape Town, South Africa: CDRA; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond RA. A Complex Systems Approach to Understanding and Combating the Obesity Epidemic. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuels S, Schwarte L, Clayson Z, Casey M. Engaging Communities in Changing Nutrition and Physical Activity Environments. Available at: http://samuelsandassociates.com/samuels/upload/ourlatest/HEAC_CCROPP_EngagingCommunities.Updated5.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2010

- 10.Samuels S, Schwarte L, Hutchinson K, Griffin N. Increasing Access to Healthy Food in the Central Valley through Farmers Markets and Produce Stand. Available at: http://samuelsandassociates.com/samuels/upload/ourlatest/CCROPP_Increasing_ACCESS_FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2010