Abstract

Cambodians in Lowell, Massachusetts, experience significant health disparities. Understanding the trauma they have experienced in Cambodia and as refugees has been the starting point for Lowell Community Health Center's whole community approach to developing community-based interventions. This approach places physical-psychosocial-spiritual needs at the center of focus and is attentive to individual and institutional barriers to care. Interventions are multilevel. The effect of the overall program comes from the results of each smaller program, the collaborations and coordination with the Cambodian community and community-based organizations, and the range and levels of services available through the health center.

KEY FINDINGS

▪ This whole community model is applicable to other refugee and immigrant populations because of its culturally centered approach that recognizes that trust and relationship building and change are processes occurring over time through repeated doses of information.

▪ The effect and strength of the approach come from the results of each program and from the collaborations, coordination, and range of services available through the health center. The practice model's effect on the community is greater than simply the sum of its parts.

▪ Multiple gateways to care and cross-referrals among the programs and to medical and behavioral health care have successfully linked Cambodian patients to the whole community of services. Community health centers are particularly well suited for such an approach.

▪ Securing funding to maintain the full scope of the whole community model is continuous. Some of the services have been adapted to be reimbursable, and the web of care is such that parts of the system can temporarily take over for other parts that may have diminished funding. The challenge of securing ongoing funding can be a weakness of the approach.

▪ Evaluation challenges were numerous: limited literacy in the community presented difficulties in design and implementation of data collection tools and evaluation plans, community health workers generally had little experience with scientific methods of evaluation and required significant training, and the evaluation plan evolved over time because of changes from the funders and developing understanding of the community.

LOWELL, MASSACHUSETTS, is home to the second largest Cambodian population in the United States; 16.5% of Lowell's population of 105 167 is Asian.1 However, based on Massachusetts Departments of Education and Public Health data, city officials and Lowell Community Health Center staff estimate that Cambodians represent 25% of Lowell's population.

Lowell Community Health Center (LCHC) is a federally qualified health center, recognized for its cultural competence and use of Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Service standards for cultural, linguistic access to care.2 In 2008, 22% of its 32 000 patients were Cambodian.

LCHC's approach to health disparities begins with understanding the trauma experienced by Cambodians under the Khmer Rouge regime. Many Cambodians starved, witnessed killings, and experienced torture and sexual assault. Those who escaped to refugee camps often found further starvation, disease, and violence.3,4 Sequelae to refugee torture and trauma, including posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, are associated with health risk behaviors5 and play a role in chronic disease management and ability to seek care.6

DISPARITIES

Cambodian Americans face poverty, limited education, and health disparities in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, related risk factors, and mental health, including posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, which influence their ability to practice prevention and obtain treatment.7–12

Cambodian women in Lowell have the highest rates of inadequate prenatal care of all Massachusetts women, and they often report domestic violence to center staff.13 Cambodian adults have relatively limited HIV prevention knowledge.12

Factors and behaviors placing Lowell's Cambodian youths at risk include disproportionate rates of adolescent pregnancy, gang involvement, sexually transmitted disease infection, substance abuse, and effects of second-generation trauma.14

Cambodian and Laotian Buddhist Monks Bless the Lowell Community Health Centers. Source: Metta Health Center Web Site.

WHOLE COMMUNITY APPROACH AND MODEL

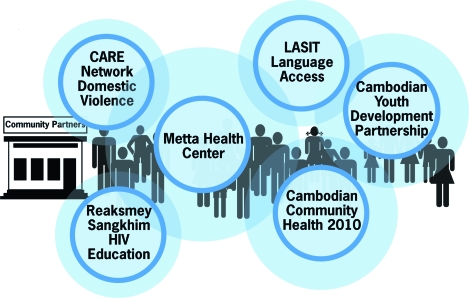

Programs addressing disparities are welcomed in this refugee community if they are part of a whole community approach (Figure 1) that focuses on collaborations, coordination, and a range of multilevel services.15,16

FIGURE 1.

The Whole Community Model: Lowell, MA

This approach places physical-psychosocial-spiritual needs at its center and is based on relationship building to promote change and recognition of generational differences and the critical role of bilingual, bicultural community health workers. This model is attentive to individual and institutional barriers to care: language, health beliefs, and limited literacy, trust levels, and understanding of US health care.

Services included in this model are as follows:

Metta Health Center: Integrates Eastern and Western approaches for primary medical, mental health, and substance abuse care, with Buddhist monks' consultations. Its largely Cambodian staff interprets, bridges cultural gaps, provides direct care, and gains patients' trust.

Cambodian Community Health 2010: Funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Cambodian Community Health 2010 offered education, support, and advocacy services on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Interventions included outreach, peer support, stress management, case management, and media programs. Cambodian Community Health 2010 evolved into the Cambodian Health Access Program, which uses a group disease self-management model and integrates community health workers into clinical care.

Cambodian Youth Development Partnership: This partnership reduces HIV transmission and substance abuse among Cambodian American youths through engagement as peer leaders and teaching assistants and involvement of parents and community partners.

Reaksmey Sangkhim: This HIV/AIDS prevention and education program provided prevention services to Cambodian adults. Interventions include outreach, a culturally adapted curriculum, and local cable advertisements.

Refugee and Immigrant Safety and Empowerment Network: This network focuses on supporting Cambodian domestic violence victims, working within a network of service providers.

Language Access System Improvement Team: This team improves access to interpreter services for patients through in-house cultural competency training, signage, and patient input.

RESULTS

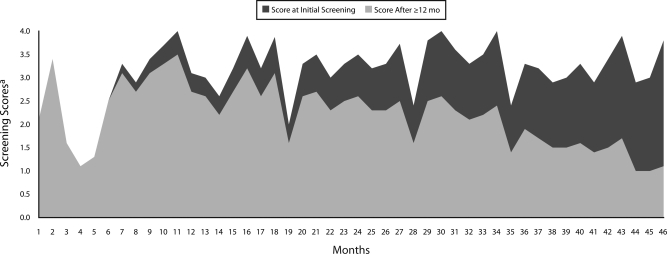

Health outcomes were made possible by building trusting relationships. The LCHC Metta Health Center improvements in depression among its patients as a result of counseling are presented in Figure 2. In the Cambodian Community Health 2010 program, all 50 diabetic patients participating in case management showed improvements over baseline: 62% in blood pressure, blood glucose, and dietary habits for disease management; 30% in medication compliance; and 11% in ability to communicate proficiently with health care providers. Participants in the Reaksmey Sangkhim program reported teaching their family, friends, and even a village in Cambodia about HIV and condom use, as well as increasing their own use of condoms. Buddhist monks now provide some HIV education to the community. Risk management assessments showed that the Language Access System Improvement Team led to an 85% reduction in risk related to medical interpreter services. More than 1000 health professionals completed cultural competence and Cambodian health beliefs training. A sample of 297 professionals completed pretest and posttest evaluations; 96% were able to identify at least 3 of 5 elements of cultural competence. In conclusion, these highlighted program results, along with additional results not discussed, establish the efficacy of the individual programs and of the whole community model of care

FIGURE 2.

Change in depression screening scores among Cambodians in treatment from intake to 12 months or more later: Lowell Community Health Center's Metta Health Center, 2008–2009.

aHopkins Symptoms Checklist 25. A score of 1.75 or higher out of 4.0 signifies symptoms of clinical depression and anxiety disorder.

Acknowledgments

George Nugent provided graphics and photographs as well as design assistance. Pat Lathrop provided the figures.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was obtained from University of Massachusetts Lowell for the Cambodian Community Health 2010 project.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau American Fact Finder: Lowell city, Massachusetts. 2000. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html?_lang=en. Accessed April 15, 2009

- 2.Putsch R, SenGupta I, Sampson A, Tervation M. Reflections on the CLAS standards: best practices, innovations and horizons. Available at: http://www.omhrc.gov/assets/pdf/checked/reflections.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2009

- 3.Chan S. Survivors Cambodian Refugees in the United States. Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinton-Davis L, Fassil Y. Health and social problems of refugees. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:507–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1075–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russon JE, Hirsch IB. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptoms reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massachusetts Department of Public Health A profile of health among Massachusetts adults, 2007: results from the behavior risk surveillance system. 2008. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/Eeohhs2/docs/dph/behavioral_risk/report_2007.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2009

- 8.NORC REACH 2010 Risk Factor Survey: Year 4 Data Report. Chicago, IL: NORC; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massachusetts Department of Public Health Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile: cardiovascular health report for Lowell. 2009. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/?pageID=eohhs2terminal&L=5&L0=Home&L1=Researcher&L2=Community+Health+and+Safety&L3=MassCHIP&L4=Instant+Topics&sid=Eeohhs2&b=terminalcontent&f=dph_masschip_r_cardio&csid=Eeohhs2. Accessed July 27, 2010

- 10.Massachusetts Department of Public Health Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile: diabetes report for Lowell. 2009. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/?pageID=eohhs2terminal&L=5&L0=Home&L1=Researcher&L2=Community+Health+and+Safety&L3=MassCHIP&L4=Instant+Topics&sid=Eeohhs2&b=terminalcontent&f=dph_masschip_r_diabetes&csid=Eeohhs2. Accessed July 27, 2010

- 11.Massachusetts Department of Public Health Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile: race/Hispanic mortality data for Lowell. 2009. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/?pageID=eohhs2terminal&L=5&L0=Home&L1=Researcher&L2=Community+Health+and+Safety&L3=MassCHIP&L4=Instant+Topics&sid=Eeohhs2&b=terminalcontent&f=dph_masschip_r_race_hispanic_mortality&csid=Eeohhs2. Accessed July 27, 2010

- 12.Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliot MN, Berthold AM, Chun C. Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. JAMA. 2005;294:571–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massachusetts Department of Public Health Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile: Perinatal report for Lowell. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/Eeohhs2/docs/dph/masschip/perinatal/perinatalcity_townlowell.rtf. Accessed December 29, 2008

- 14.Daud A, Skoglund E, Rydelius PA. Children in families of torture victims: transgenerational transmission of parents' traumatic experiences to their children. International Journal of Social Welfare. 2005;14:23–32 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simons-Morton BG, Greene WH, Gottlieb NH. Introduction to Health Education and Health Promotion. 2nd ed.Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland; 1995 [Google Scholar]