Abstract

We provide a historical study of the anti-alcohol public health poster in Poland between 1948 and 1990. Our case study illuminates public health policies under communism, with the state as the dominant force in health communication. Poland has a distinctive history of poster art, moving from a Stalinist phase of socialist realism to the diverse styles of the later Polish School. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of 213 posters establishes the major themes and differentiates community approaches, which depict the drinker as a social or political deviant, from those emphasizing individual risk. Medical issues were a minor theme, reflecting public policies geared more toward confinement than treatment. However, Polish School artists used metaphor and ambiguity, and references to the contested cultural symbolism of drink, to complicate and subvert the narrow propaganda intent. Thus, although apparently unsuccessful in restraining overall consumption, these posters offer valuable lessons for policymakers on the use of visual media in health campaigns.

ALTHOUGH ITS ORIGINS LIE IN commercial advertising, the poster was used throughout the twentieth century as a medium for the dissemination of public health messages.1 Until recently, analysis by historians was limited to collection-based studies that emphasized design rather than broader context.2 However, the resurgence of public health posters during the AIDS epidemic has prompted -renewed historical interest in the form.3 More generally, historians increasingly advocate visual media as a source for exploring the contested terrain of understanding between lay audiences, medical professionals, and the state.4 We present findings drawn from a larger study of the public health poster in Poland between the country's independence in 1918 and the fall of communism in 1989. Its focus is one of the major preoccupations of propaganda posters in the postwar period: the drinking of alcohol.

There is a substantial contemporary literature both on the poster as an instrument of health communication and on the use of visual media in anti-alcohol campaigns. Evaluations of the effectiveness of health posters in modifying behavior are numerous; crudely, they show that sometimes these posters produce only limited changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practice, but at other times, especially in mixed-mode campaigns, they contribute to -improved health outcomes.5 The second approach deals with poster content, drawing on the methodological tools of cultural studies to consider how meaning is conveyed through visual images. Here, the aim is to sharpen the awareness of commissioning agents about how poster messages may be read, internalized, or rejected according to the social and cultural context in which they appear.6

Within the alcohol literature, evaluative studies are also numerous, with the poster typically considered alongside other communication media. Again, the evidence for success is mixed, suggesting that informational or persuasory campaigns typically have no direct effect on long-term consumption patterns.7 They can, however, have an impact on knowledge and attitudes, and may therefore be effective when integrated with other policies, such as drunk-driving messages alongside enhanced policing, or in preparing public opinion for more effectual environmental measures, such as advertising bans or licensing restriction.8

This equivocal evidence for success, whether of poster campaigns alone or, more broadly, of mass media health campaigns, has also prompted a more skeptical literature. Criticism centers on the concern that efforts to affect individual behavior place public health officials in a disciplinary or moralizing posture, and may serve to enforce inequalities. In areas such as obesity, alcohol, and smoking, mass media campaigns are arguably “little more than public relations exercises” on the part of the state, designed to proclaim concern while avoiding more meaningful actions at the population level that would offend vested economic interests.9 More broadly, poorly designed campaigns may stigmatize vulnerable populations through visual and textual representations, thereby creating a “counterpublic” that actively resists medical advice.10

The purpose of a historical study is to contribute to critical reflection. Although retrospective evaluation is obviously impossible, a historical perspective can be helpful in analyzing what has been called the “circuit of mass communication” in health campaigns.11 This concept embraces the range of interactions involved in the formulation and reception of health messages. These include the influences acting on the state in the preparation of campaigns, whether from medicine, nongovernmental organizations, or politicians; the content and delivery of the message, whether by advertisers, artists, or journalists; the recall, understanding, and diverse responses of viewers; and, finally, the subsequent impact on behavior and policy that completes the circuit. By concentrating on Eastern Europe under communism, we can provide an interesting contrast to previous studies, for here were societies in which the capacity of the media and of civil society to shape governmental approaches was considerably restricted. Here, too, the propaganda poster was widely and systematically deployed to mold other forms of social behavior and political loyalties according to ideological tenets.12

POLAND AS A CASE STUDY

The turbulent politics of twentieth-century Poland make it a particularly interesting subject for a study in health policy. It achieved independence in 1918 after a long period of partition between Germany, Austria, and Russia, then in World War II suffered successive invasions from Hitler's and Stalin's armies, losing one third of its population, including 2.9 million Jews.13 When the Iron Curtain descended, Poland became a Soviet satellite and was in effect, if not formally, a one-party state in which civil society was suppressed. There were periodic glimmers of liberalism—in the cultural thaw of 1956, in the student protests of 1968, and in workers’ demonstrations of 1970 and 1976. However, authoritarian control was always reestablished, and a command economy pursued growth through central planning, under the premierships of Wladyslaw Gomulka (1956–1970) and of Edward Gierek (1970–1980). In 1980, the failure of the economy to supply consumer goods and contain prices led to the rise of the Solidarity trade union and forceful demands for political reform. Martial law and dictatorship followed under General Wojciech Jaruzelski, although continuing support for trade unions ultimately rendered the communist state untenable. Political pluralism and democracy were finally restored in 1989 and 1990.14

In the communist period, then, health policy was highly centralized and aligned with political and economic imperatives. For example, an antituberculosis program was written into the Six-Year Plan (1951–1956), explicitly linking prevention with industrial production.15 Public health messages, like all forms of published communication, were subject to state censorship, which in Poland functioned “not merely as an instrument of negative suppression, but also … as a means of active propagation.”16 With respect to alcohol, the state dominated the antidrinking lobby while at the same time monopolizing the production of spirits, from which it drew substantial revenues.17 Independent Catholic and secular temperance groups were swallowed in 1948 and 1949 by a new state-controlled body, and in 1956 the officially sanctioned Central Social Anti-alcohol Committee was founded by the party. Thus, distribution and control policies were “entirely monopolized by the state apparatus.”18

Excessive consumption of vodka has a long history in Poland, which had been a significant producer of the spirit since the eighteenth century.19 Historically, vodka drinking had positive associations: it marked religious and communal celebrations, signified hospitality, and was used as a reciprocal gesture accompanying mutual aid. However, twentieth-century urbanization removed the customary constraints operating in rural society and exposed drinkers to more plentiful availability.20 In the postwar period, if measured in liters of pure alcohol per capita (among those aged 15 years and older), consumption rose from 4.2 liters in 1950 to 5.7 liters in 1960, 7.0 liters in 1970, and 9.1 liters in 1975 before peaking (following a small dip in 1978 and 1979) at 11.1 liters in 1980. Rationing was introduced during the political and economic crisis of 1981, after which levels fell to 9.4 liters in 1985 and 9.3 liters by 1989.21

Trends in vodka, wine, and beer drinking mirrored this pattern, although beer consumption began to diminish slightly earlier.22 In comparative terms, the Polish experience was unexceptional: of the 29 countries for which Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development data on per capita alcohol consumption for 1981 to 2001 are available, Poland ranked below the United States and the United Kingdom and was substantially behind France and Spain.23 Poles, however, tended toward heavy drinking at a single session.24

Analysis of the medical effects, such as hospital admissions for alcoholism or alcohol psychoses or mortality rates for cirrhosis of the liver, unambiguously demonstrates the close relationship between consumption and disease.25 Similarly, crime statistics chart the escalation of alcohol-fueled social problems, such as road accidents caused by drunk drivers and homicides and rapes committed while intoxicated. Rates of alcohol-related public order offenses actually fell beginning in the mid-1950s, although this reflected the less punitive strategy, introduced in 1956, of overnight detention without charge in a “sobering station.”

In essence, government policy emphasized the institutional confinement of alcoholics while simultaneously encouraging the supply of alcohol to the population at large. The 1956 legislation also inaugurated a network of alcohol treatment centers in which courts could compulsorily detain alcoholics, a policy that deterred those seeking care voluntarily. Institutionalization therefore served to isolate and contain, but not to offer medical or psychiatric interventions beyond exploitative regimes of work therapy, through which patients provided cheap labor for local employers.26 Meanwhile, the government made only limited attempts to use price levers to curb drinking and pursued a liberal approach toward licensing and sales, a key factor driving up consumption in the 1960s and 1970s.27 Only in 1981 were tighter controls on supply imposed, as both Solidarity and the (teetotaler) General Jaruzelski adopted anti-alcohol policies in the struggle for moral superiority between trade union and state.28 Through most of the period under review, then, the policy context of anti-alcohol poster campaigns was one of increasing exposure of the population to alcohol, coupled with a disciplinary and deterrent response to alcoholism.

Finally, Poland's suitability for study also arises from the distinctive history of its poster art, typically dated to the emergence of a new graphic style in interwar Warsaw.29 After 1945, this gave way to Soviet influence and censorship, ushering in the artistic doctrine of “socialist realism,” whose unsophisticated, narrative style of propaganda sought to mold a “new, socialistic people.”30 Further profound changes followed Stalin's death in 1953 and the subsequent thaw, which saw the emergence of the internationally acclaimed Polish School of posters. Associated mainly with theater, circus, and film advertising, the movement fostered high artistic values, drawing on symbolism, macabre imagery, and a wide range of styles, including surrealism, expressionism, formalism, and pop art.31 Realism was rejected as artists now strove to create a poster that was “a reflection, sign, symbol, which calls forth a reaction and stimulates the imagination.”32 This penchant for metaphor and ambiguity also created a space for critique and subversion, and in the 1980s the poster became an instrument of democratic propaganda, supporting the Solidarity movement.33

We begin by detailing the methodology we apply to the analysis of the posters. We then present an overview of the themes of the collection and the nature of the appeals, and an exploration of the changing styles and content through the postwar period. Here, we consider the implications for health messages of the artistic innovations of the Polish School. We conclude by suggesting that at the population level, the anti-alcohol poster appears to have been broadly ineffectual. Indeed, study of its content reveals an ideal of socialist citizenship that the authoritarian state wished to project but that proved ultimately unachievable. We also highlight the symbolic power of alcohol and the scope that this symbolism provided for artists of the Polish School to undermine or complicate the messages intended by those who commissioned the posters.

POSTER ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY

We surveyed more than 50 major national and local repositories in which visual artifacts are collected and identified 995 public health posters. A total of 259 had an anti-alcohol theme, of which we viewed 213.34 A literature search elicited relevant secondary material that placed the production of anti-alcohol posters within its epidemiological, political, and socioeconomic context. We then carried out a quantitative analysis, following the methodology proposed by Emmison and Smith. They argued that quantification can legitimately be applied to visual material, provided the sampling frame is robust and the coding categories are consistent throughout the period surveyed.35 We believe that we have a reasonably comprehensive sample, first because our major archive, the Wilanow Poster Museum, is a repository dedicated to Poland's national and local poster history, and second because those located in the smaller archives mostly duplicated those already recorded.

We categorized the posters according to their main and subsidiary themes and, where possible, by commissioning body. To explore long-term change, we organized the collection into 4 periods: 1945 to 1956, the Stalinist era; 1957 to 1968, the Gomulka years and the cultural thaw; 1960 to 1979, the Gierek years and the dash for economic growth; and 1980 to 1989, the period of Solidarity, military rule, and the ultimate collapse of communism. Such time-series data also provide a basis for the generation of hypotheses, as well as guiding selection for qualitative work.37

We then used this overview to address 2 existing historical interpretations of Polish anti-alcohol propaganda, hitherto based principally on textual sources. Amsterdamska has argued that this propaganda served the needs of the state, with alcoholism first represented as political deviance, before the emphasis moved to the financial cost to families as central planning sought to promote economic growth.38 Laskowska-Otwinowska saw instead a shift from community-oriented persuasion—emphasizing themes such as reconstruction and national unity—to more individualized messages in the 1990s.39 Our analysis builds on these insights, but argues that both are too narrow to capture the thematic range and intended recipients of the anti-alcohol poster.

Our qualitative methodology is an adaptation of that developed by Johnny and Mitchell in their study of cross-cultural readings of AIDS posters.40 Drawn from visual communication theorists deconstructing commercial advertisements, this approach follows the Barthean distinction between the “denoted” meaning (the image as analog of reality) and the “connoted” meaning (cultural resonances that lend significance to the viewer).41 Their method moves from consideration of the poster's “narrative” (the surface “story”) to the “intended meaning” (the informational or exhortatory purpose), the “ideological meaning” (the implicit values and social assumptions), and finally the “oppositional reading” (unintended alternative interpretations that some spectators might impose).42

The peculiarities of the Polish case necessitate 3 further considerations. First, in decoding connoted meanings, the usual critical intent in the West is to expose assumptions prevalent in market institutions about, for example, class, gender, or the economic order. In our study, it was the bureaucratic socialist state that acted either as direct or de facto commissioning agent for the poster and that, through direct or indirect censorship, constrained its content. We may therefore expect that, at the level of both intent and ideology, posters will be expressions of the state's political project.

Second, it is also possible that there are encoded meanings attributable to the artist, and potentially running counter to official ideology; as one artist put it, “The slogan and the requirements … belong to the customer, the artistic arrangement to me.”43 This was because the Polish School and its successors shunned literalism in favor of signs and metaphors whose import might escape the censor or commissioner. Its essence was “not to make the viewer look, but to make him think and perceive … the more interpretative possibilities there are, the more diverse the responses it evokes.”44

Third, this potential for multiple readings is enhanced by the symbolic resonance of drinking in Polish literary and political culture. Amsterdamska's study of alcohol in fiction and poetry demonstrated that drunkenness functioned as a “polysemic trope,” deployed as both “symbol and symptom of a sick political reality.”45 A readiness to confer political meaning on drinking arose partly from a long-standing theme of Polish temperance literature, that those in power (from feudal landlords to the partitioning powers to the Nazis) had deliberately “pushed” alcohol onto the people, both for profit and to dull resistance.46 Indeed, the political opposition of the 1980s condemned drinking as part of the machinery of oppression.47 In the Gdansk shipyard strike that heralded the arrival of Solidarity, a policy of strict temperance was enforced to project an image of “calm, moderation and discipline.”48 Solidarity's program later called for a strong anti-alcohol policy, accusing the state of “pushing” drink so the nation could be “controlled and manipulated.”49 Conversely, the state periodically used the charge of “drunken hooliganism” to discredit political opposition—for example, in the student demonstrations of 1968 and the workers’ protests in the 1970s.50 Therefore, any attempt to “read” images of alcohol, even in the banal context of public service posters, must be undertaken with these plural and ambiguous connotations in mind.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

Our quantitative findings are based on the 213 anti-alcohol posters that we were able to view directly (Table 1). The sample included major poster artists, such as Marian Bogusz and Bronislaw Linke from the socialist realist phase, and several leading exponents of the Polish School and its successors, such as Waldemar Swierzy, Jan Sawka, Roslaw Szaybo, Jerzy Czerniawski, Maciej Urbaniec, Andrzej Pagowski, and Wojciech Freudenreich. Thus, the public health theme may legitimately be situated within the broader history of the Polish poster. Of the commissioning bodies identified, the most significant was the Central Social -Anti-alcohol Committee (64 posters), with the “WAG”—the Graphical Artistic Publishing House—also significant (31). A lesser role was played by the Ministry of Health and its institutes (10), the Central Committee of the Trade Unions (13), the Society of Sobriety for Drivers (12), and the Polish Red Cross (6). It should be stressed that these last 3 bodies cannot be viewed as independent voluntary associations on the Western model. We found only 2 posters from nongovernmental agencies, both produced by the Catholic church in the 1980s.

TABLE 1.

Number of Anti-alcohol Posters, by Time Period and Theme: Poland, 1945–1989

| 1945—56 | 1957—68 | 1969—79 | 1980—89 | Total | |

| Family | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 13 |

| Individual | |||||

| Medical | 2 | 6 | 23 | 10 | 41 |

| Behavior | 9 | 19 | 7 | 35 | |

| Community | |||||

| Economic | 2 | 15 | 15 | 2 | 34 |

| Accidents | 6 | 12 | 14 | 5 | 37 |

| Violence | 1 | 7 | 2 | 10 | |

| Social | 15 | 10 | 5 | 30 | |

| Youth | 8 | 5 | 13 | ||

| TOTAL | 13 | 78 | 89 | 33 | 213 |

Note. Themes covered are as follows: under “family,” impact on children and family life, and eugenics; under “individual, medical,” physical, sexual, and mental health, illicit alcohol risk, and mortality risk; under “individual, behavior,” morality, career, and status; under “community, economic,” poverty and consumption and national productivity; under “community, accident,” road, workplace, and home; under “community, violence,” domestic violence and disorder; under “community, social,” leisure, sports, tourism, national image, and crime; under “community, youth,” fashion, leisure, and impact on education.

Most of the posters in our study were produced in the 1960s and 1970s. Assuming that the relative scarcity of posters in the earlier and later phases is not an artifact of archiving trends, it seems likely that anti-alcohol work was a lesser priority in the Stalinist phase, when consumption was comparatively low, and also in the 1980s, when policy switched to constraining supply. Poster production was therefore most abundant in the period of liberal drinking policies and rising consumption.

Our sample allowed us to evaluate Laskowska-Otwinowska's differentiation of the “community” from the “individual” poster. Focusing only on the narrative and intended meanings, we distinguished posters that addressed the viewer as individual or family member from those that appealed to him as part of broader society (the gendered pronoun is deliberate: women were rarely represented, appearing only as victims of abuse or as idealized figures designed to incentivize male sobriety). Just over 40% were in the “family” and “individual” categories, and these appear throughout the period 1945 to 1989. Laskowska-Otwinowska is therefore incorrect to suggest that the transformation to individualized propaganda occurred only after 1990. Similarly, Amsterdamska's emphasis on the themes of political deviance and financial cost alone is inadequate.

Our statistical analysis also permits the identification of major and minor themes and their trends over time. First, it is striking how marginal purely medical appeals to abstention are. Only 31 posters deal with physical health, including personal accidents, and all but 4 are post-1968; a further 7 directly address psychiatric impacts, even though the problem of alcohol psychosis was known. Addiction also barely features, although it is obliquely tackled in metaphorical works such as Jasinski's 1977 image of a cognac glass in which a spider's web is suspended.51 Government anti-alcohol strategies were geared to containing disorder, so this relative absence mirrored and legitimized a policy with little capacity for medical or self-help responses.

Conversely, then, many posters represented the drinker as social deviant, whether at the intended or ideological level of meaning. Of these, 35 accused the drunk of failing to contribute to the economy, either as industrial producer (only 2 address farmers) or as consumer; these were predominantly from the Gomulka–Gierek years. A recurrent theme was the opportunity cost of expenditure on drink, often with representations of forgone material goods: food and small items in the 1940s and 1950s, motorbikes and apartments in the 1960s. The irony here was that although the economy consistently failed to meet the appetite for consumer goods, drinking remained comparatively cheap and easily available. Recreation provided another field in which the drinker was depicted as antisocial, with sport and -tourism the concern in the 1960s and rural leisure pursuits in the 1970s. Another example is drink-associated violence, which emerged as a theme in the mid-1960s; a textual addition to one poster suggests that this was triggered by the pace of urban migration by young men.52

Beyond this, there were also many posters whose ideological content was less overt. Drunk-driving posters were particularly numerous (14% of the sample) and served principally to communicate the risk as dramatically as possible. The number of these posters peaked in the 1970s, the subject shifting from the truck driver to the private motorist. A recurrent characteristic of the genre was a funereal black background and sparse imagery of motor vehicles, often accompanied by skeletal hands or a skull as a somber memento mori.53 Many of the other posters encouraging behavior change eschewed messages about social status or conformity in favor of direct appeals, whether focused on risk of injury or the emotional stresses associated with alcoholism. As we will now see, in all these genres Polish poster artists used the medium of public health messages to explore the diverse social meanings of drink.

CONTENT ANALYSIS

Socialist realism: 1945–1956

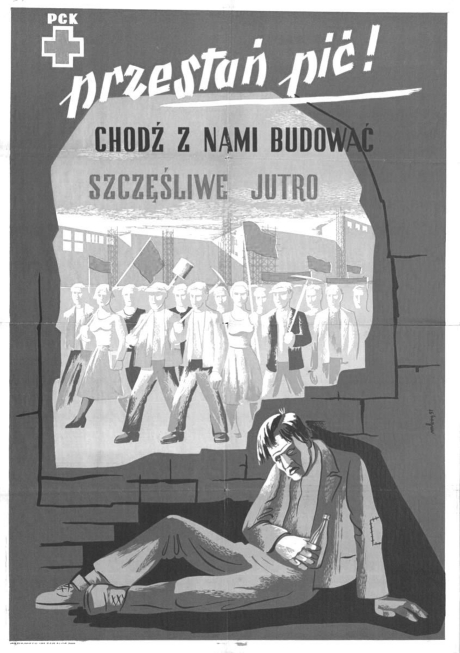

Cultural policy in the immediate postwar period was under direct Soviet influence, and the officially sanctioned style was socialist realism. This rejected expressionism in favor of unmediated representation and simple narrative, whether in cartoon strip or picture format. The assumption was that proletarian art must abandon high aesthetics in favor of easily understood messages whose purpose was to advance socialism. Bogusz's Stop Drinking! (Figure 1) epitomizes this aim of yoking the health message to political imperatives. The narrative is of the alcoholic as shirker, with the intended meaning conveyed through the binary opposition of light and shade that signal the drinker's moral failure. Ideological meaning is expressed by the landscape of flags, factories, and marching workers representing the national reconstruction effort that the alcoholic evades. Linke's image Vodka Causes Poverty similarly demonized the drinker, although here economic indolence was in the home, where a brutalized wife and child emphasized the otherness of the alcoholic's squalid world.

FIGURE 1.

Marian Bogusz, Stop Drinking! Come With Us and Build a Better Tomorrow, 1952.

Source. Jagiellonian Library, Krakow.

Realism, however, was not always used to depict the drinker as pariah or to advance a political agenda. Romanowicz, for example, used a comic strip style to issue simple, didactic warnings to the individual against drunk driving, or the risks faced by the children of alcoholics. The eugenic message in his work harks back to a prewar theme of Polish temperance.54 Thus, the Stalinist period was characterized by friction between the newer Soviet-influenced model emphasizing national productive imperatives and earlier indigenous anti-alcohol messages.

Impact of the Polish School of poster: 1956–1968

The design revolution in the cultural thaw following Stalin's death marked a decisive break from realist representation. Stylistic eclecticism was the Polish School's hallmark, as 2 examples demonstrate. Dziatlik's The -Return of Daddy (Figure 2) revisits the narrative theme of family breakdown, but from a startlingly original perspective. Now the viewer sees through the child's eyes and must impose her or his own meaning, whether around the stupefaction of the irresponsible father or the terror of domestic violence. Ideological meanings are also unfixed: the caption is the title of a celebrated work by the 19th-century romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, in which the prayers of his children bring a father safely home. This adds both a level of irony and a religious connotation in a nation which remained deeply Catholic despite official secularism. The poster's references therefore hold an oppositional significance at a juncture when Polish communism was distancing itself from Soviet dominance; indeed, in 1968 the banning of a play by Mickiewicz was to trigger the student protests.55

FIGURE 2.

Dziatlik, The Return of Daddy, 1957.

Source. Jagiellonian Library, Krakow.

Urbaniec's classical rendition of an Olympic athlete (Figure 3) also speaks to a familiar theme of anti-alcohol propaganda: the harmful effects of drinking on sport and leisure pursuits. The surface intent is to promote abstention through the message that drinking undermines sporting prowess, but the choice of the heroic athlete as subject also invokes ideological associations. Sporting achievement had long figured in Soviet and Polish political propaganda, because it asserted both the competitive superiority of Eastern Bloc nations and the centrality of physical culture to the building of socialist society.56 Drawing on Leninist ideas about the importance of the healthy body to the happy citizen-worker, state policies promoted “fitzkultura” as a civic duty to strengthen its military and industrial workforce.57 The sporting hero was a modern icon, typically represented in a frontal pose, brimming with triumphal optimism.58

FIGURE 3.

Maciej Urbaniec, Don't Drink Away All You Have Achieved, 1964.

Source. Wilanow Poster Museum, Warsaw.

Urbaniec, however, presents an inverted posture, with the face in shadow, as if to deny the conventional ideological meaning. Is he signaling Polish rejection of Soviet dominance? The international sporting arena was, after all, somewhere Poles could legitimately express national pride independently of the Soviet Union, and the year of production, 1964, saw their unprecedented success at the Olympic Games. Or does he intend to reclaim sporting achievement for individualistic aspiration? His own view was

Sport and art are united by one of the most luminous humanistic ideas. Striving for perfection, attainment and the transcending of the limits of human powers lie at the core of that idea.59

Legacy of the Polish School: 1968–1980

Even though the claims for free expression made by students and intellectuals in 1968 were quickly swept aside, poster art lost none of its diversity, ebullience, and fondness for loaded symbolism. Both the early members of the Polish School and the postwar generation they trained continued to produce innovative work of stylistic variety. Western influences such as psychedelia and pop art were now at the fore in the output of artists such as Cesarska and Swierzy.60 At the ideological level, such posters signaled the state's tolerant incorporation of the Western counterculture in marketing conformist messages to the young. But, arguably, they also expressed oppositional elements, alluding to drugs, sex, and rock music at a time when censors forbade all mention of the “hippie movement” that was not “unequivocally -critical.”61

Other artists explored the use of metaphor, often in photomontage, to convey risk or damage to the individual: a half-burnt candle, a drunk slumped astride an outsize wheel, a man walking underwater, a face made up of distorted concentric circles, and so on.62 There was also a return to figurative work and more painterly styles by the “Wroclaw Quartet” of New Wave poster artists.63 Holidays and outdoor pursuits provided a popular subject in this vein, with colorful scenes of bucolic relaxation. The reasons for this propaganda focus are not clear, although the provision of revitalizing leisure time for the worker was a long-standing socialist promise, now being fulfilled as paid holidays increased.64 At the ideological level, then, these posters represented both national prosperity and a benevolent compact between state and people, although their theme is more often private and familial pleasures.

The system in collapse: 1980–1989

Work from the 1980s provides various examples of more overt oppositional meanings encoded in alcohol posters. The political salience of drinking became the subject of public debate in 1980, when Solidarity leaders accused the state of “pushing” alcohol and aligned their protest with abstention. Thus, the familiar theme of sobriety in the workplace took on a different ideological import, as the earlier productivist message rang hollow in the face of economic disaster. Janowski's depiction of a worker's gloved hand sealing an open vodka bottle, under the caption “Be a friend,” surely represents Solidarity, with the hand's outsized perspective indicating the power of numbers over a dangerous opponent.

The political potency of anti-alcohol imagery is also illustrated by Jacek Cwikla's untitled work (Figure 4), an image whose checkered history was described to us by the artist. This originated as an apolitical image recognizably within the traditions of the genre, which Cwikla intended as a concise metaphor for the mortality risks of alcohol, devoid of ideological implications. The -censor, however, interpreted it as an inflammatory work. Political tensions were running high following the murder of pro-Solidarity priest Father Popieluszko, and the concern was that the poster might invite graffiti from dissidents hostile to the Jaruzelski regime. Publication was duly suspended, although eventually the censor relented and the poster appeared. So, as the fall of communism approached, the diverse connotations surrounding the imagery of drinking could elude even the artist himself. Such was the hall of mirrors that was the Polish anti-alcohol poster.

FIGURE 4.

Jacek Cwikla, Untitled, 1984.

Source. Central Medical Library, Warsaw.

EFFECTS OF POLISH ANTI-ALCOHOL POSTERS

Returning now to the circuit of mass communication, what does this history of the anti-alcohol poster reveal of how health messages develop and interact with the public? Polish health propaganda did not emerge within the context of political pluralism, as in the West,65 but within a one-party state working through organizations staffed by the nomenklatura system, which guaranteed the appointment of loyal officials approved by the communist party. Alternative channels of public discourse about alcohol's social effects were unavailable, as censorship of the press muzzled both serious discussion and even minor reportage that might undermine faith in socialist achievement.66 Nor, until 1979, was sustained academic research on the nature and impact of alcoholism commissioned, and even then its findings were only narrowly disseminated.67

Alcohol policy, just as in the West, was therefore influenced not by public health considerations but rather by commercial interests—here, particularly those of agricultural producers and catering concerns, and by the state's own perception of the importance of alcohol to economic stability.68 It therefore embodied a fundamental contradiction. Excessive drinking must be curbed because it transgressed the ideals of socialist citizenship, yet the production and consumption of alcohol must be encouraged because it was fundamental to the socialist economy. Crucially, the spirits industry was a linchpin of the state's revenue, generating some 9% of its budget by the 1970s.69 This meant that the posters discussed here were not an element of a broader public health strategy—quite the contrary, given the policy context.70

Thus, although detailed retrospective evaluation is beyond the historian's ambit, these anti-alcohol posters can reasonably be judged to have been a failure at the population level. Although they conceivably may have slowed the rate of increase in consumption, they did not halt its upward trend, which fell only with the supply-side changes of the 1980s. It is ironic that the rate of poster production was highest in the era of the most liberal supply policies, and although deliberate intent is unlikely, this effectively provided a smokescreen, signaling the state's -concern while obscuring its complicity. A similar argument has been made about the communist propaganda poster more generally: that it chiefly operated as “a legitimating discourse … a field for the regime to picture themselves to themselves and their people.”71 The ideological content conjured an idealized reality, where industrial workers willingly labored to meet planners’ goals, where shops were filled with consumer goods and where populations gladly engaged in sport and exercise to fulfill personal and patriotic ends. We have as yet located no evidence of the viewers’ reception of these works, beyond the commonplace observation that Poles were weary of censorship and fundamentally skeptical of instructional propaganda. Therefore, just as in the Western examples noted in the introduction, the Polish case suggests that where alcohol education is undertaken in the absence of other control strategies, the result is widespread resistance to its messages.

That said, our content analysis, and our contextualization of the genre within the broader history of Polish poster art, suggests that it was open to highly complex and diverse readings that went beyond the ideological intent of commissioning bodies. The “drinker as deviant” approach never predominated, and throughout the period there were commonalities with noncommunist societies in the posters that directly addressed the individual. Subject matter ranged from risk of accidents and drunk driving to the depredations of alcohol on behavior, family life, and mental stability. The commissions also offered Polish poster artists a considerable degree of latitude in the creative process. Anti-alcohol messages presented them with a subject whose cultural and political resonance went far beyond the narrow public health intent. They could therefore bring to bear the same panoply of styles and symbolism deployed in their more celebrated works for theater and cinema, and give full rein to their proclivity for unfixed, sometimes subversive, meanings.

This raises the possibility that although population-level impacts are not discernible in the 1960s and 1970s, the steady presence of visual messages may have played a part in shifting the climate of public opinion. Perhaps the combination of individual appeals and politically tinged images underpinned Solidarity's temperance position and indirectly contributed to the curbs of the 1980s. That said, the “rapid and substantial increase in alcohol consumption” that followed market deregulation in the 1990s suggests that such a reading is overoptimistic.72

Ultimately, then, the absence of contemporary evaluations means that speculation about positive effects of anti-alcohol posters must remain uncertain. Perhaps the most striking lesson of the Polish case is that even the most elaborate and accomplished visual exhortations need to be accompanied by economic policies that limit exposure if they are to have an impact. This history also provides a reminder, were it needed, that those planning preventive campaigns must be fully alert to the diverse cultural and political meanings that drinking holds for the populations they seek to influence.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust under its International Collaborative Research Grants scheme and by the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland (NN-2-006/07); it was also partially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Republic of Poland (0031/B/P01/2009/37).

We express our gratitude to the Jagiellonian Library, the Wilanow Poster Museum, the Central Medical Library, Warsaw, and Jacek Cwikla for their help and permission to publish the posters -illustrating this article.

Endnotes

- 1. D. Crowley, “The Propaganda Poster,” in The Power of the Poster, ed. M. Timmers, (London: V & A Publications, 1998), 101–145, see 103, 110–111; M. Sappol, An Iconography of Contagion (Bethesda, Maryland: National Academy of Sciences, 2008)

- 2. M. Robert-Sterkendries and P. Julien, Posters of Health (Brussels: Therabel, 1996)

- 3. S. Gilman, Picturing Health and Illness: Images of Identity and Difference (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 115–172.

- 4. V. Berridge and K. Loughlin, “Smoking and the New Health Education in Britain 1950s–1970s,” American Journal of Public Health 95, no. 6 (2005): 956–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. For recent examples, see D. Ashe, P. A. Patrick, M. M. Stempel, Q. Shi, and D. A. Brand, “Educational Posters to Reduce Antibiotic Use,” Journal of Paediatric Health Care 20, no. 3 (2006): 192–197; O. Bankole, G. Aderinokun, and O. Denloye, “Evaluation of a Photo-Poster on Nurses’ Perceptions of Teething Problems in South-Western Nigeria,” Public Health 119, no. 4 (2005): 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. L. Johnny and C. Mitchell, “ ‘Live and Let Live’: An Analysis of HIV/AIDS-Related Stigma and Discrimination in International Campaign Posters,” Journal of Health Communication 11, no. 8 (2006): 755–767; T. Rhodes and R. Shaughnessy, “Selling Safer Sex: AIDS Education and Advertising,” Health Promotion International 4, no. 1 (1989): 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. G. Edwards, P. Anderson, T. Babor, et al., Alcohol Policy and the Public Good (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1994), 172–175, 180; K. Jochelson, “Nanny or Steward? The Role of Government in Public Health,” Public Health 120 (2006): 1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. For example, see W. deJong, “The Role of Mass Media Campaigns in Reducing High-Risk Drinking Among College Students,” Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement 14 (2002): 182–192; G. Agnostelli and J. W. Grube, “Alcohol Counter Advertising and the Media: A Review of Recent Research,” Alcohol Research and Health 26, no. 1 (2002): 15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. D. Lupton, The Imperative of Health: Public Health and the Regulated Body (London: Sage, 1995), 124–130, quote on 129.

- 10. C. L. Briggs, “Why Nation States and Journalists Can't Teach People to Be Healthy: Power and Pragmatic Miscalculation in Public Discourses on Health,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17, no. 3 (2003): 287–321. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. D. Miller, J. Kitzinger, K. Williams, and P. Beharrell, The Circuit of Mass Communication (London: Sage, 1998)

- 12. J. Aulich and M. Sylvestrova, Political Posters in Central and Eastern Europe 1945–95 (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1999)

- 13. N. Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland, Volume II (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2005), 344, 365.

- 14. A. Kemp-Welch, Poland Under Communism (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

- 15. B. Markiewicz, “Tuberculosis in Poland, 1945–1995: Images of a Disease,” in Images of Disease: Science, Public Policy and Health in Post-War Europe, ed. I. Lowy and J. Krige (Luxembourg: European Communities, 2001), 257–290, see 267.

- 16. Davies, God's Playground, 406.

- 17. J. Moskalewicz, “The Monopolization of the Alcohol Arena by the State,” Contemporary Drug Problems 12 (Spring 1985): 117–128, see 122–123.

- 18. K. Moczarski, History of Alcoholism and the Fight Against It (Warsaw: SKP, 1980), 15; Moskalewicz, “Monopolization of the Alcohol Arena,” 125–126, quote on 126.

- 19. B. Rok, “Counteraction Against Alcoholism in Religious Letters of 18th Century [in Polish],” Medycyna Nowozytna 6, no. 2 (1999): 62–77. [PubMed]

- 20. Here we assume that findings from Imperial Russia apply to pre-independence Poland; K. Transchel, Under the Influence: Working-Class Drinking, Temperance And Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1895–1932 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006), 37, 123, 152; P. Herlihy, The Alcoholic Empire: Vodka and Politics in Late Imperial Russia (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2002), 92–93, see 140; M.-R. Rialand, L'alcool et les Russes (Paris: Institut des Etudes Slaves, 1989), 71–72.

- Data for 1950 to 1980 are from J. Morawski, “Alcohol-Related Problems in Poland, 1950–81,” in Consequences of Drinking: Trends in Alcohol Problem Statistics in Seven Countries, ed. N. Giesbrecht, M. Cahannes, J. Moskalewicz, E. Österberg, and R. Room (Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation, 1983), 2; data for 1985 and 1989 are from “OECD Health Data 2009—Selected Data: Risk Factors,” available at http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CSP2009 (accessed October 16, 2009)

- J. Moskalewicz and J. Sierosławski, “Differentiation in Alcohol Consumption in Poland in the 1980s [in Polish],” Problemy Medycyny Społecznej 8 (1986): 252–255.

- 23. Taking the mean of figures for 1981 through 2001, odd years only; OECD Health Data 2009.

- 24. J. Moskalewicz, Social Policies Related to Alcohol in Poland, 1944–1982 [in Polish] (Warsaw: State Agency of Alcohol Related Problems, 1998), 46.

- 25. All data are from Morawski, “Alcohol-Related Problems” and I. Wald and J. Moskalewicz, “Alcohol Policy in a Crisis Situation,” British Journal of Addiction 79 (1984): 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. J. Moskalewicz and G. Swiatkiewicz, “Deviants in a Deviant Institution: A Case Study of a Polish Alcohol Treatment Hospital,” Contemporary Drug Problems 16 (Summer 1989): 157–176.

- 27. J. Moskalewicz, “Alcohol as a Public Issue: Recent Developments in Alcohol Control in Poland,” Contemporary Drug Problems 10 (Spring 1981): 11–21, see 11–12; I. Wald et al., Raport o problemach polityki wobec alkoholu (Warsaw: Instytut Wydawniczy Zwiazków Zawodowych, 1981)

- 28. I. Wald and J. Moskalewicz, “Alcohol Policy in a Crisis Situation,” British Journal of Addiction 79 (1984): 331–335, see 335; J. Moskalewicz, “Lessons to Be Learnt From Poland's Attempt at Moderating Its Consumption of Alcohol,” Addiction 88 (Supplement 1993): S135–S142, see S139. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. M. Kurpik, “Time, Artists and the Poster,” in Posters From the Poster Museum at Wilanow Collection, ed. M. Kurpik and A. Szydolska (Warsaw: Muzeum Narodowe w Warsazawie, 2008): 26–51; J. Barnicoat, Posters: A Concise History (London: Thames and Hudson, 1972): 135, 145–146.

- 30. Aulich and Sylvestrova, Political Posters, 23–25; A. Szydolska 2008, “Posters of the Stalinist Period in Poland: From Socialist Realism to Pop Culture,” in Posters From the Poster Museum at Wilanow Collection, 196–201.

- 31. S. Wrede, The Modern Poster (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988), 37; Kurpik, “Time, Artists and the Poster.”.

- 32. J. Lenica, “Documentacja Obrad Sympozium Zorganizowanego z Okazji 1 Miedzynarodowego Biennale Plakatu, Warszawa,” 1966, cited in Posters From the Poster Museum at Wilanow Collection, 88.

- Crowley, “The Propaganda Poster,” 133–134.

- 34. Locations are as follows: 479 posters in the Wilanow Poster Museum and 150 in the Central Medical Library, Warsaw; 243 in the Jagiellonian Library and 37 in the Academy of Fine Arts, Krakow; and 86 in the Silesian Library, Katowice.

- 35. M. Emmison and P. Smith, Researching the Visual: Images, Objects and Interactions in Social and Cultural Inquiry (London: Sage, 2000), 61–63.

- 36. D. Parszewska, “Poster Museum at Wilanow—Genesis, Form and Function,” in Posters From the Poster Museum at Wilanow Collection, 10–17.

- 37. Emmison and Smith, Researching the Visual, 58–63.

- 38. O. Amsterdamska, “Drinking as a Political Act: Images of Alcoholism in Polish Literature, 1956–89,” in Images of Disease. Science, Public Policy and Health in Post-War Europe, ed. I. Lowy and J. Krige (Luxembourg: European Communities, 2001), 309–327, see 325.

- 39. J. Laskowska-Otwinowska, “Community and Individual Changes in Propaganda Against Alcoholism,” in Images of Disease, 329–352, see 332–338.

- 40. Johnny and Mitchell, “Live and Let Live.”.

- 41. R. Barthes, Image Music Text, trans. S. Heath (London: Fontana, 1977), 17–18, 33–37; K. Toland Frith, “Undressing the Ad: Reading Culture in Advertising,” in Undressing the Ad: Reading Culture in Advertising, ed. K. Toland Frith (New York: Peter Lang, 1998), 1–17, 131–149.

- 42. Johnny and Mitchell, “Live and Let Live,” 760, 766.

- 43. J. Zielecki, “Andrzej Pagowski,” in Andrzej Pagowski, ed. M. Kurasiak (Warsaw: Foundation of Polish Culture, 1989), 9–13, quote at 12.

- 44. Aulich and Sylvestrova, Political Posters, 175, 177; Kurpik, “Time, Artists and the Poster,” 40.

- Amsterdamska, “Drinking as a Political Act”; Images of Disease, 309, 325.

- Moskalewicz, “Monopolization of the Alcohol Arena,” 117–120; Herlihy, Alcoholic Empire, 131–133; Transchel, Under the Influence, 35–36.

- 47. N. Andrews, Poland 1980–81: Solidarity Versus the Party (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1985), 177.

- 48. A. Bielewicz and J. Moskalewicz, “Temporary Prohibition: The Gdansk Experience August 1980,” Contemporary Drug Problems 11 (Fall 1982): 367–381, 369–371; “Solidarity Strike Bulletin no. 8,” in The Solidarity Sourcebook, ed. S. Perky and H. Flam (Vancouver: New Star, 1982), 88.

- 49. Quoted in Moskalewicz, “Lessons to Be Learnt,” 139; J. Moskalewicz, “Alcohol as a Public Issue: Recent Developments in Alcohol Control in Poland,” Contemporary Drug Problems 10 (Spring 1981): 11–19, 16.

- 50. Bielewicz and Moskalewicz, “Temporary Prohibition,” 373; Moskalewicz, “Lessons to Be Learnt,” 137; Kemp-Welch, Poland Under Communism, 210.

- 51. Jarosław Jasinski, Have the Courage to Say No, 1977, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 19954.

- 52. Witold Janowski, He Wanted to Be a Good Friend, 1966, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 5167.

- 53. For example, see Zbigniew Słomczynski and Gustaw Majewski, Vodka, 1956, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 2808/1-3; Marek Mosinski, Untitled, 1968, Jagiellonian Library, XVI 5'68.

- 54. M. Gawin, “Progressivism and Eugenic Thinking in Poland, 1905–1939,” in Blood and Homeland: Eugenics and Racial Nationalism in Central and Southeast Europe, 1900–1940, ed. M. Turda and P. Weindling (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2007), 167–183.

- 55. Kemp-Welch, Poland Under Communism, 148–157.

- 56. M. O'Mahony, Sport in the USSR: Physical Culture—Visual Culture (London: Reaktion, 2006), 16–17.

- 57. Ibid, 15–20, 55–56, 138–139, 176–178.

- 58. Ibid, 43–50, 121; M. Lafont, Soviet Posters (London: Prestel, 2007), 111, 117, 121, 125, 131, 136, 154, 169, 170, 172, 191.

- 59. Cited in Aulich and Sylvestrova, Political Posters, 151.

- 60. Danuta Cesarska, Its Cool to Party Without Alcohol, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 19085; Waldemar Swierzy, Alcohol Can Also Transmit Venereal Diseases, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 15368.

- 61. The Black Book of Polish Censorship, ed. J. Leftwich Curry (New York: Random House, 1984), 152.

- 62. Tomasz Jura, Do Not Drink Away Your Life, 1970, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 14792; Janusz Wiktorowski, The Drunken Loafer, 1973, Jagiellonian Library, XVI 5'73; Wojciech Freudenreich, Watch Out, Alcohol Is Dangerous, 1976, Jagiellonian Library, XVI 5'76; Marek Freudenreich, 1970, Alcohol Disturbs Precision of Thought, Wilanow Poster Museum, Pl. 14615.

- Kurpik, “Time, Artists and the Poster,” 45; Aulich and Sylvestrova, Political Posters, 55.

- 64. W. Roszkowski, The New Polish History (Warsaw: Puls Publications, 1991), 932.

- 65. See D. Miller and K. Williams, “The AIDS Public Education Campaign, 1986–90”; Miller et al., Circuit of Mass Communication, 13–45.

- 66. Black Book of Polish Censorship, 5, 214–218; Moskalewicz, “Alcohol as a Public Issue,” 14.

- Moskalewicz, “Lessons to Be Learnt,” 137; I. Wald, J. Morawski, and J. Moskalewicz, “Alcohol and Alcohol Problems Research, 12. Poland,” British Journal of Addiction 81 (1986): 729–734. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68. J. Moskalewicz and J. Simpura, “The Supply of Alcoholic Beverages in Transitional Conditions: The Case of Central and Eastern Europe,” Addiction 95, Supplement 4 (2000): S505–S522, S509–S510. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moskalewicz, “Lessons to Be Learnt,” 136.

- Moskalewicz, “Alcohol as a Public Issue,” 11–12.

- 71. Aulich and Sylvestrova, Political Posters, 3.

- 72. B. Wojtyniak, J. Moskalewicz, J. Stokwiszewski, and D. Rabczenko, “Gender-Specific Mortality Associated With Alcohol Consumption in Poland in Transition,” Addiction 100 (2005): 1779–1789, quote on 1786. [DOI] [PubMed]