Abstract

Background

We have previously observed that donor bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells successfully induce transient mixed chimerism and renal allograft tolerance following non-myeloablative conditioning of the recipient. Stem cells isolated from the peripheral blood (PBSC) may provide similar benefits. We sought to determine the most effective method of mobilizing PBSC for this approach and the effects of differing conditioning regimens on their engraftment.

Methods

A standard dose (10 μg/kg) or high dose (100 μg/kg) of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) with or without stem cell factor (SCF) was administered to the donor and PBSC were collected by leukapheresis. Cynomolgus monkey recipients underwent a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen (total body irradiation, thymic irradiation and ATG) with splenectomy (splenectomy group) or a short course of anti-CD154 antibody (aCD154) (aCD154 group). Recipients then received combined kidney and PBSC transplantation and a one-month post transplant course of cyclosporine.

Results

Treatments with either two cytokines (GCSF+SCF) or high dose GCSF provided significantly more hematopoietic progenitor cells than standard dose GCSF alone. Recipients in the aCD154 group developed significantly higher myeloid and lymphoid chimerism (p<0.0001 and p=0.0002, respectively) than those in the splenectomy group. Longer term renal allograft survival without immunosuppression was also observed in the aCD154 group, while two of three recipients in the splenectomy group rejected their allografts soon after discontinuation of immunosuppression.

Conclusions

Protocols including administration of two cytokines (GCSF + SCF) or high dose GCSF alone significantly mobilized more PBSC than standard dose GCSF alone. The recipients of PBSC consistently developed excellent chimerism and survived long-term without immunosuppression, when treated with CD154 blockade.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, nonhuman primates, tolerance, mixed chimerism, peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, leukapheresis

Introduction

Based on rodent studies (1, 2), we have previously defined a conditioning regimen that provides successful induction of renal allograft tolerance following combined kidney and donor bone marrow transplantation in nonhuman primates (NHP) (3, 4). This protocol has now been successfully extended to human recipients of HLA mismatched kidneys (5).

In the previously reported monkey studies, we transplanted donor bone marrow cells (BMC), either aspirated from the iliac crest of live donors or procured from the vertebral bones of euthanized donors. The dose of DBMC received by those recipients ranged from 0.5 – 4.0 × 108 mononuclear cells (MNC)/kg. The nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, including 3 Gy total body irradiation (TBI), 7 Gy thymic irradiation (TI) and antithymocyte globulin (ATG), successfully induced transient mixed chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in approximately 60% of treated recipients in our cynomolgus monkey model (6). We have continued to refine the protocol in the attempt to reduce the toxicity of the therapeutic regimen and to possibly increase the consistency of tolerance induction. One possible approach would be substitution of PBSC for BMC. The use of PBSC for autologous or allogeneic transplantation has several reported advantages over BMC. These include less invasive collection methods, reduced morbidity, and faster engraftment and immune reconstitution (7-9). However, in PBSC transplantation (PBSCT), the risk of recipient sensitization may be higher, since much larger doses of donor cells (10 – 100 times) are typically infused in PBSCT than in BMC transplantation. In the current study, we sought to define the efficacy of PBSCT via the following aims;

Evaluate the effect of various granulocyte stimulating factor (GCSF) and stem cell factor (SCF) therapeutic regimens on the mobilization of PBSC.

Evaluate the levels of chimerism inducible by PBSC after a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen;

Evaluate the role of splenectomy versus CD154 blockade for preventing sensitization following high-dose PBSC infusion.

Materials and Methods

Animals

27 Male cynomolgus monkeys that weighed 3 to 7 kg were used (Charles River Primates, Wilmington, MA). All surgical procedures and postoperative care of animals were performed in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of primates and were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Animal Research.

Mobilization of PBSC

Four cytokine protocols consisting of standard dose (10 μg/kg) or high dose (100 μg/kg) recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF, Filgastrim, Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA) with or without porcine stem cell factor 500 μg/kg (SCF; Biotransplant Inc, Charlestown, MA) were tested in the donor animals. The growth factors were administered daily for 7 days by subcutaneous injections into the flanks.

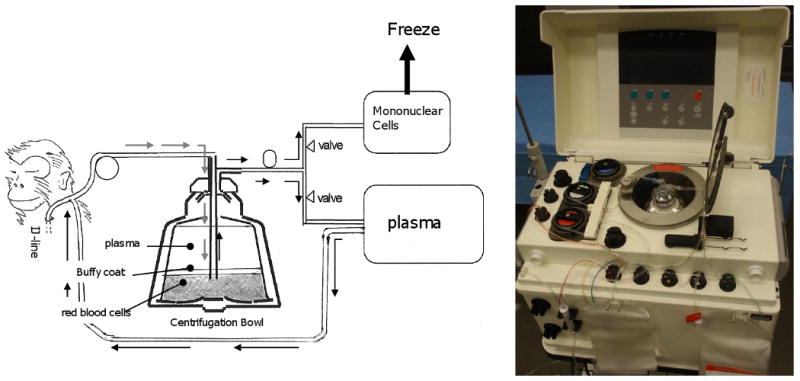

Leukapheresis (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. Leukapheresis procedure.

Vascular access for leukapheresis was achieved using a 9 Fr single lumen catheter placed in the internal jugular vein. The Haemonetics MCS + LN9000 Blood Cell Separator (Haemonetics Corp, Braintree, MA) was used to collect the PBSC. The apheresis kit was primed with 120 ml of irradiated, citrated ABO compatible monkey blood. Prior to initiating the leukapheresis, 100 U/kg of heparin was administered to the donor monkey. The monkey blood collected in the bowl was centrifuged at 5500 rpm and blood components and other solutions were separated to their specific gravity. Automated recovery of mononuclear cells was performed and other blood components were returned to the animal (one recovery cycle). Procedure was continued until four recovery cycles were completed. Collected mononuclear cells were frozen and stored at -72°C.

Vascular access for leukapheresis was achieved using a 9 Fr. single lumen catheter placed in the right internal jugular vein. The Haemonetics MCS + LN9000 Blood Cell Separator (Haemonetics Corp, Braintree, MA) was used to collect the PBSC. The apheresis kit was primed with 120 ml of irradiated, citrated ABO compatible monkey blood. Prior to initiating the leukapheresis, 100 U/kg of heparin was administered to the donor monkey. An automated MNC recovery was then performed at 20 ml/min for 4 recovery cycles (1800 ml – 2500 ml). Frequent vital sign monitoring was performed throughout the procedure and if hypotension developed, intravenous dopamine was infused. At the completion of each cycle, red blood cells and plasma were re-infused into the donor during the next cycle. After completion of the last cycle, red blood cells in the bowl were retrieved and infused back into the donor, after which the internal jugular and the peripheral catheters were removed.

Colony Forming Cell (CFC) Assays

To evaluate hematopoietic progenitor cells, we employed the CFC assay. Mononuclear cells were isolated from the leukapheresis product by gradient centrifugation over freshly prepared 60% isotonic Percol (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Contaminated red blood cells were removed by standard water-shock treatment. Cell counts and viability were assessed by eosin dye exclusion. Mononuclear cells were added to methylcellulose medium with recombinant cytokines (Methocult GF + H4435, Stem Cell Technologies Inc., Vancouver, Canada) in a 1:10 ratio. After mixing well, the medium was dispensed into Petri dishes (1 ml/dish) and the cells incubated for 14 days in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Colony types were counted and evaluated using an inverted microscope and gridded scoring dishes. The colony-forming units-granulocyte/macrophage (CFU-GM) was expressed as a mean value of CFU-cells detected per million cells plated (± standard errors).

CFU/ml in the leukapheresis product was calculated as; CFU/ml=MNC (million)/ml × CFU/million MNC plated.

Conditioning regimen for Kidney / PBSC Transplantation

The nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen consisted of a nonmyeloablative dose of TBI (1.5 GyX2) on days -6 and -5; TI (7 Gy) on day -1; and equine ATG (ATGAM, Pharmacia and Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI, 50 mg/kg/day on days -2, -1 and 0). Splenectomy was performed in three recipients (Splenectomy group). Anti-CD154 mAb (aCD154, American Type Culture Collection catalog number 5c8.33, 20 mg/kg) was administered on days 0 and 2 in an additional three recipients (aCD154 group) in place of splenectomy. All recipients underwent combined kidney / PBSC transplantation on day 0. Kidney transplantation was performed intra-peritoneally with end-to-side anastomosis between donor renal vessels (vein / artery) and recipient cava / aorta. The donor ureter was then anastomosed to the recipient bladder in extravesical fashion. (10). The recipients also underwent unilateral native nephrectomy and ligation of the contralateral ureter on day 0. This approach provides a means to rescue the recipient, by untying the native ureter, if prolonged acute tubular necrosis (ATN) develops in the transplanted kidney. The remaining native kidney was removed later, between 60 – 80 days after transplantation. All recipients were treated with a one-month post transplant course of subcutaneously administered cyclosporine (CyA) (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) (tapered from an initial dose of 15 mg/kg/day) to maintain therapeutic serum levels (>200 ng/ml). CyA was discontinued on day 28 post-transplant, after which serum CyA levels typically became undetectable by day 60.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

After standard water shock treatment, peripheral blood cells were first stained with donor-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAb) chosen from a panel of mouse anti-human HLA class I mAbs that cross-react with cynomolgus monkeys. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C, and then washed twice. Cell-bound mA b was detected with fluorescein isothiothianate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse immunoglobulin IgG2a mAb (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), which was incubated for 30 min at 4°C, followed by two washes and analysis on FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). In all experiments, the percentage of cells that stained with each mAb was determined from one color fluorescence histogram and was compared with those obtained from donor and pretreatment frozen recipient cells, which were used as positive and negative controls. The percentage of cells considered positive was determined with a cutoff chosen as the fluorescence level at the beginning of the positive peak for the positive control stain and by subtracting the percentage of cells stained with an isotype control. By using forward and 90° light scatter (FSC and SSC, respectively) dot plots, lymphocyte (FSC- and SSC-low), granulocyte (SSC-high), and monocyte (FSC-high but SSC-low) populations were gated, and chimerism was determined separately for each population. Nonviable cells were excluded by propidium iodide staining.

Statistical methods

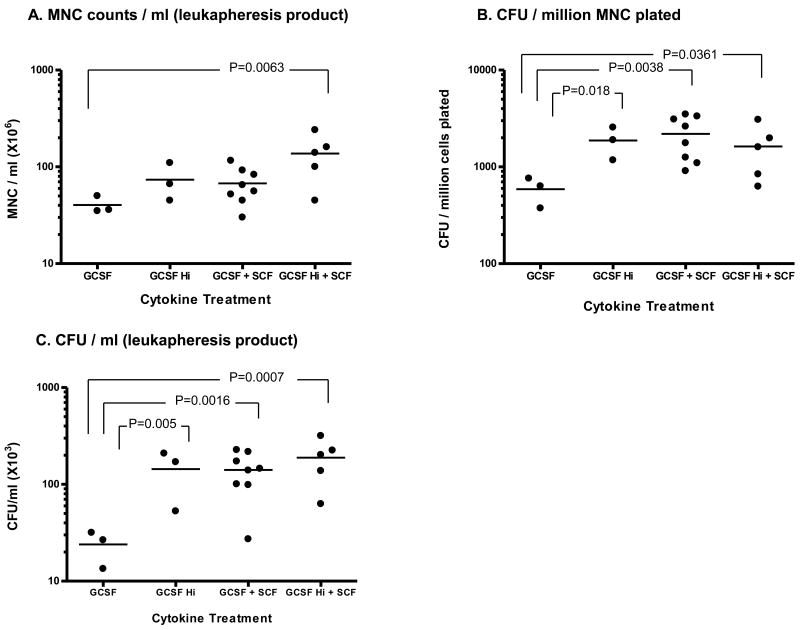

CFU Assays (Fig. 2): We analyzed the data using a log transformation to make the data normally distributed. Then, two way analysis of variance was used to evaluate the effects of each factor, dose of GCSF (High vs. Standard), and the use of SCF (Yes vs. No). We tested for the effects of each factor (GCSF and SCF) and for the interaction between the two factors. Pairwise differences of the four treatment groups were also calculated.

Figure 2. MNC counts and CFU yield in leukapheresis product.

Leukapheresis was performed seven days after cytokine treatment and MNC and CFU counts in the leukapheresis product were measured.

A: The average MNC count was significantly higher in the high GCSF+SCF group (137 ± 32.4 × 106 /ml) than in the standard dose GCSF alone group (p=0.0063). The GCSF and the GCSF+SCF regimens provided somewhat lower MNC counts but these were not significantly different.

B: CFU / million MNC was significantly higher in two cytokine protocols (GCSF Hi+SCF, GCSF+SCF) and high dose GCSF, comparing with the standard dose GCSF alone group, (p=0.0361, 0.0038 and 0.018, respectively).

C: CFU/ml leukapheresis product was significantly higher in two cytokine protocols (GCSF+SCF, GCSF Hi+SCF) and high dose GCSF than in the standard dose GCSF alone group (p=0.0007, 0.0016 and 0.005, respectively).

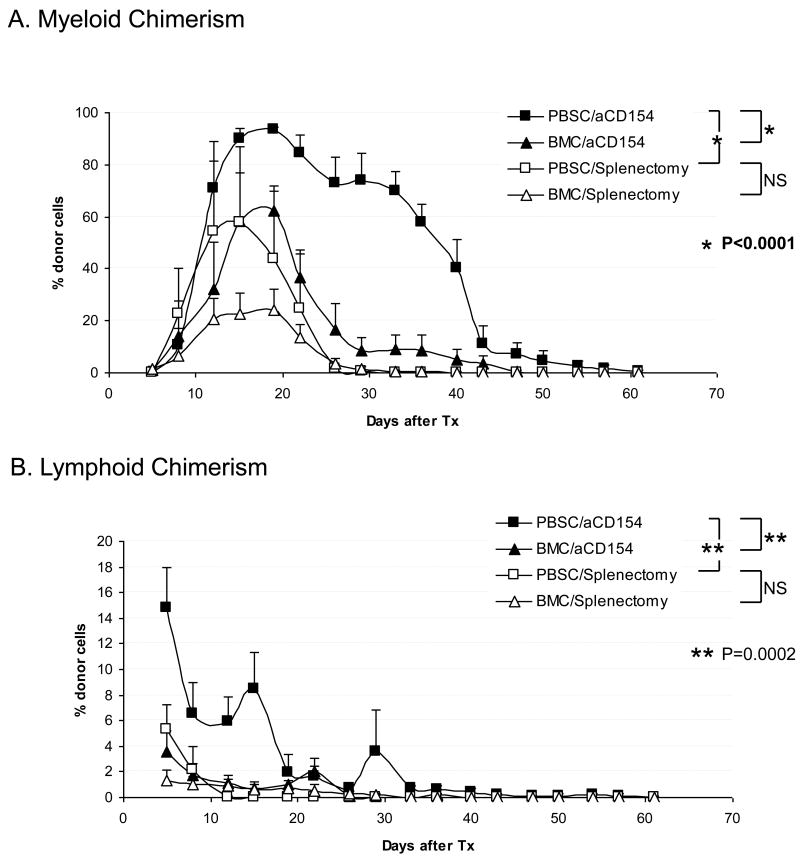

Chimerism Data (Fig. 3): Generalized estimating equations were used to test whether there was difference between splenectomy vs. aCD154 groups or BMC vs. PBSC over the whole time course of the experiment (11). The two factors were PBSC vs. BMC and aCD154 vs. Splenectomy.

Figure 3. Chimerism induction.

A Myeloid chimerism; The levels of myeloid chimerism observed were significantly higher in the PBSC/aCD154 group than in the PBSC/splenectomy group (p<0.0001). When compared with our previous results observed in recipients treated with BMC (4), no statistically significant difference was seen between PBSC/Splenectomy (n=3) and BMC/Splenectomy (n=11) groups. There was, however, a significant difference (p<0.0001) between PBSC/aCD154 (n=4) and BMC/aCD154 (n=4) in the levels of myeloid chimerism.

B. Similar to the observations with myeloid chimerism, levels of lymphoid chimerism were significantly greater in the PBSC/aCD154 group than the PBSC/Splenectomy group (p=0.0002). In comparison with our previous results with BMC, (PBSC/aCD154) recipients developed significantly higher (p=0.0002) lymphoid chimerism than the BMC/aCD154 recipients. There was no significant difference observed between the recipients receiving PBSC versus BMC and treated with the Splenectomy regimen.

Results

Cytokine treatment and PBSC yield by leukapheresis

Leukapheresis was performed on day 7 after cytokine therapy. Typically 65 to 75 ml of leukapheresis product was obtained with 4 cycles. To evaluate the effect of the different cytokine protocols, we first counted mononuclear cells (MNC) (million cells/ml) in each leukapheresis product (Fig.2A) and then an aliquot of MNC was added to methylcellulose medium with recombinant cytokines (see method). After incubation for 14 days, the number of colonies was counted (CFU-cells detected per million cells plated, Fig.2B). Finally, CFU per one ml of the leukapheresis product was calculated by multiplying MNC counts by CFU/million MNC (Fig. 2C).

The average MNC count (Fig. 2A) was greatest in the high GCSF+SCF group (137 ± 32.4 × 106 /ml), which was significantly higher (p=0.0063) than MNC counts in the standard dose GCSF alone group. The two way analysis of variance showed a significant independent effect of GCSF dose (p=0.02) and a nearly significant effect of SCF (p=0.052)

CFU / million MNC (Fig. 2B) was significantly higher in two cytokine protocols and high dose GCSF alone group than in the standard dose GCSF alone group (1622 ± 437 in GCSF Hi+SCF, 2192 ± 375 in GCSF+SCF and 1875 ± 400 in GCSF Hi vs. 588 ± 114 in GCSF, p=0.0361, 0.0038 and 0.018, respectively).

CFU per one ml of the leukapheresis product (Fig. 2C) was significantly higher in the two cytokine protocols (188.6 ± 42.5 in GCSF Hi+SCF × 103, 140.9 ± 23.3 × 103 in GCSF+SCF and 188.6 ± 42.6 × 103 in high dose GCSF + SCF) than in the GCSF alone group (23.9 ± 5.5 × 103) (p=0.0007, 0.0016 and 0.005, respectively), The two way analysis of variance showed significant independent effect in both GCSF dose and SCF use (p=0.0069 and p=0.0076 respectively). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the high dose GCSF group and two cytokine groups (GCSF+SCF or high dose GCSF+SCF).

Induction of mixed chimerism after PBSCT

Six renal allograft recipients received PBSC transplantation mobilized in the donor by two cytokine (either GCFS+SCF or high dose GCFS + SCF) protocols. These results with PBSC were also compared with the previously reported results with BMC (3, 4, 12).

In the myeloid lineage (Fig. 3A), PBSC recipients treated with aCD154 developed significantly higher levels of chimerism than those observed in PBSC recipients with splenectomy (p<0.0001). In the recipients treated with aCD154, PBSC induced significantly higher chimerism (p<0.0001) than BMC, while no such difference was found in recipients treated with splenectomy. There was also a significant interaction of the two factors (PBSC vs. BMC and aCD154 vs. Splenectomy) (p<0.0336). Similar significant differences (p=0.0002) were also observed in the lymphoid lineage (Fig.3B).

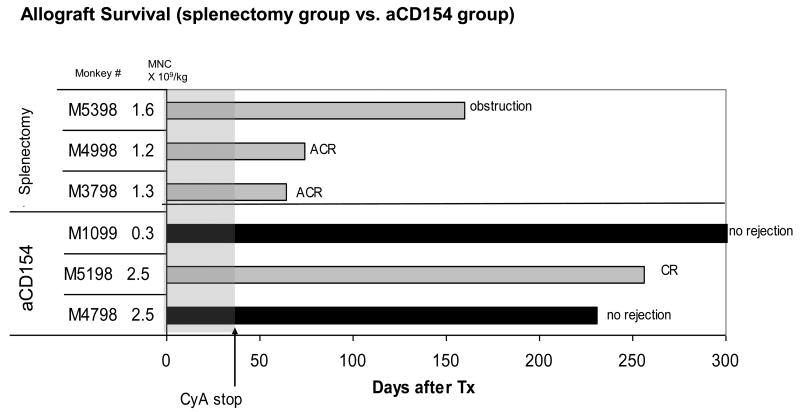

Renal allograft survival after PBSCT

Two of three PBSCT recipients in the splenectomy group acutely rejected their allografts soon after discontinuation of CyA. The third recipient in this group survived until day 160 without rejection but died due to urinary obstruction caused by a urethral stone. In contrast, two of three PBSCT recipients in the aCD154 group survived long-term without rejection after discontinuation of CyA. The third monkey in this group also survived long-term, but eventually developed anti-donor antibody and succumbed to chronic rejection (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Renal allograft survival after PBSCT.

Leukapheresis product with the MNC dose up to 2.5 × 109/kg was infused in the splenectomy group (n=3) or aCD154 group (n=3). In the splenectomy group, only one recipient (M5398) survived long-term without rejection (died due to ureteral stone). Two other recipients rejected their renal allografts soon after discontinuation of CyA. In the aCD154 group, all three recipients survived long-term after discontinuation of CyA. Two of them have never developed anti-donor antibody and survived long-term without rejection. The third recipient (M5198) developed anti-donor antibody and eventually rejected the renal allograft with chronic rejection.

Discussion

In the current study, the initial step was to evaluate the efficacy of various cytokine regimens for mobilizing PBSC. We tested GCSF and SCF, since both cytokines have been reported in less detailed studies to effectively mobilize PBSC in rhesus monkeys and baboons (13, 14). Probably because of limited cross reactivity of human cytokines with cynomolgus monkey receptors, we found that the usual human dose of recombinant GCSF was not sufficient to effectively mobilize PBSC in our monkeys but that a higher dose (100 μg/kg) or addition of SCF was effective. We show that SCF acted synergistically with GCSF, mobilizing significantly more PBSC than the standard dose GCSF alone (Fig. 1). However, there was no significant difference between high dose GCSF and the two cytokine protocol (either GCSF + SCF or high dose GCSF + SCF), leading us to conclude that high dose GCSF treatment alone may be sufficient to mobilize PBSC, if one desires to avoid the use of SCF.

The second objective of this study was to evaluate the levels of chimerism induced by PBSC infusions. The leukapheresis product obtained following cytokine mobilization was infused into 6 recipients of the nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen including either splenectomy or aCD154. The levels of mixed chimerism were significantly higher after PBSCT than the chimerism observed in our previous studies after BMT (3,4,12) when treated with aCD154 (Fig 3). Nevertheless, as in the previous private studies, permanent mixed chimerism was not achieved in these recipients. This contrasts with the observations that have been reported in swine, where the mixed chimerism induced after high-dose PBSCT was more durable (15). It should be emphasized, however, that, in the swine model, stable chimerism was achieved by infusing 1 – 5 × 1010 MNC/kg. This significantly higher dose of PBSC (10 times greater than in our private studies)) was obtained by selecting adult pigs (30-40kg) as donors and young pigs (<10kg) as recipients to take advantage of the significant size discrepancies. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that more than 1 × 1010 MNC/kg might also induce stable hematopoietic chimerism in primates.

This possibility is supported by studies in nonhuman primates, by Kean et al., who reported longer term mixed chimerism following PBSCT in rhesus monkeys (16). Their conditioning protocol consisted of busulfan, anti-CD25R mAb, costimulatory blockade (anti-CD28 / CD154), sirolimus and donor specific transfusion. With this more intensive and more prolonged immunosuppressive protocol and higher doses of MNC (up to 6.8 × 109/kg), they observed chimerism for as long as 196 days. Nevertheless, stable chimerism following discontinuation of immunosuppression was never achieved.

To collect the apparently required higher doses of hematopoietic progenitor cells, additional donor leukaphereses could be attempted. In our study, we used the Haemonetics MCS + LN9000 Blood Cell Separator to collect PBSC. This automated system was easy to use but required more than 250 ml of volume to prime the circuit. Thus, priming the system with irradiated 3rd party blood and careful monitoring during the procedure were necessary for the small cynomolgus monkey, in which the estimated blood volume is less than 500 ml (55-75 ml/kg). In the studies by Kean et al. or by Ageyama et al., the Cobe Spectra (Gambo BCT, Lakewood, CO) was used to collect PBSC. Although Cobe Spectra has a similar priming volume (285ml), its constant extracorporeal flow may provide increased safety for these relatively small animals undergoing multiple leukaphereses.

The last aim of this study was to evaluate whether PBSC can induce long-term renal allograft survival, comparable to that achieved by BMC in our previous studies. In those initial studies, two of three recipients of the standard conditioning regimen but without splenectomy rejected their renal allografts shortly after discontinuation of CyA (12). The spleen represents the largest lymphoid tissue site of the body, accounting for about 25% of the total body lymphocyte pool. When a large number of donor cells are infused in non-splenectomized recipients, most of the donor cells are probably sequestered in the spleen, where donor antigens are presented effectively to both T and B cells (17, 18). We concluded that the effective T-B cell collaboration in the spleen resulted in production of anti-donor antibody, leading to antibody mediated rejection of the allograft Our further studies showed that splenectomy is an effective approach in preventing antibody mediated rejection (12) in recipients whose dose of infused donor cells was up to around 2 × 108 cells/kg. The observations in the current study, however, suggest that splenectomy is not sufficient to prevent sensitization when a larger dose of donor cells (more than 109 /kg) are infused. Another approach to preventing antibody mediated rejection in our mixed aneurysm protocols has been incorporation of a short course of CD154 blockade into the conditioning regimen in place of splenectomy. We have shown this to be effective in recipients of combined kidney and BMC transplantation (4). In contrast to the negative results (2/3 early rejection) observed in recipients of PBSC and treated with splenectomy, evaluation of PBSCT in recipients of a CD154 resulted in long-term survival in all 3 recipients after discontinuation of CyA. Thus, a short course of CD154 blockade appears to be more effective than splenectomy in preventing sensitization after infusion of large numbers of donor cells. Additional studies of monkeys will be undertaken to validate these preliminary results.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that PBSC can be effectively mobilized by either high dose GSF or the combined cytokine treatment with GCSF and SCF. Transplantation of PBSC with doses up to 2.5 × 109 cells/kg induced significantly improved levels of transient mixed chimerism than BMT but failed to induce long-term stable chimerism. PBSCT also demonstrated comparable results to those using BMC with respect to prolonged renal allograft survival, when used along with CD154 blockade. Further advantages of PBSCT in our mixed chimerism approach remain to be tested with even larger doses of PBSC.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by 5U19DK080652-02 NHL-BI, POI-HL18646, NIH-NIAID, ROIA137692 and NIH/NIAID 5R01 AI50987-03.

We thank Dr. Elizabeth Smoot for statistical analysis, Patricia Della Pelle for pathological analysis and Drs. Michael Duggan and Elisabeth Moeller for anesthesia and postoperative care.

Abbreviations

- PBSC

peripheral blood stem cells

- PBSCT

peripheral blood stem cell transplantation

- DBMC

donor bone marrow cell

- BMC

bone marrow cells

- BMT

bone marrow transplantation

- MNC

mononuclear cells

- GCSF

granulocyte colony simulating factor

- CFU

colony forming unit

- CFU-GM

colony forming unit-Granulocute/Monocyte

- SCF

stem cell factor

- NHP

nonhuman primates

- TBI

total body irradiation

- TI

thymic irradiation

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sharabi Y, Sachs DH. Engraftment of allogeneic bone marrow following administration of anti-T cell monoclonal antibodies and low-dose irradiation. Transplant Proc. 1989;21(1 Pt 1):233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sykes M, Sachs DH. Mixed chimerism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1409):707. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Colvin RB, et al. Mixed allogeneic chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 1995;59(2):256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawai T, Sogawa H, Boskovic S, et al. CD154 blockade for induction of mixed chimerism and prolonged renal allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(9):1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Spitzer TR, et al. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimikawa M, Sachs DH, Colvin RB, Bartholomew A, Kawai T, Cosimi AB. Modifications of the conditioning regimen for achieving mixed chimerism and donor-specific tolerance in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 1997;64(5):709. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199709150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyer J, Schwella N, Zingsem J, et al. Hematopoietic rescue after high-dose chemotherapy using autologous peripheral-blood progenitor cells or bone marrow: a randomized comparison. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(6):1328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann O, Le Corroller AG, Blaise D, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell and bone marrow transplantation for solid tumors and lymphomas: hematologic recovery and costs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(8):600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitz N, Linch DC, Dreger P, et al. Randomised trial of filgrastim-mobilised peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation versus autologous bone-marrow transplantation in lymphoma patients. Lancet. 1996;347(8998):353. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosimi AB, Delmonico FL, Wright JK, et al. Prolonged survival of nonhuman primate renal allograft recipients treated only with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. Surgery. 1990;108(2):406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai T, Poncelet A, Sachs DH, et al. Long-term outcome and alloantibody production in a non-myeloablative regimen for induction of renal allograft tolerance. Transplantation. 1999;68(11):1767. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199912150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews RG, Briddell RA, Knitter GH, et al. In vivo synergy between recombinant human stem cell factor and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in baboons enhanced circulation of progenitor cells. Blood. 1994;84(3):800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donahue RE, Kirby MR, Metzger ME, Agricola BA, Sellers SE, Cullis HM. Peripheral blood CD34+ cells differ from bone marrow CD34+ cells in Thy-1 expression and cell cycle status in nonhuman primates mobilized or not mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and/or stem cell factor. Blood. 1996;87(4):1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchimoto Y, Huang CA, Yamada K, et al. Mixed chimerism and tolerance without whole body irradiation in a large animal model. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(12):1779. doi: 10.1172/JCI8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kean LS, Adams AB, Strobert E, et al. Induction of chimerism in rhesus macaques through stem cell transplant and costimulation blockade-based immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(2):320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford WL. Lymphocyte migration and immune responses. Prog Allergy. 1975;19:1. doi: 10.1159/000313381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprent J, Miller JF, Mitchell GF. Antigen-induced selective recruitment of circulating lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1971;2(2):171. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(71)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]