Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma accounts for about 80–90% of all liver cancer and is the fourth most common cause of cancer mortality. Although there are many strategies for the treatment of liver cancer, chemoprevention seems to be the best strategy for lowering the incidence of this disease. Therefore, this study has been initiated to investigate whether thymoquinone (TQ), Nigella sativa derived-compound with strong antioxidant properties, supplementation could prevent initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis-induced by diethylnitrosamine (DENA), a potent initiator and hepatocarcinogen, in rats. Male Wistar albino rats were divided into four groups. Rats of Group 1 received a single intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection of normal saline. Animals in Group 2 were given TQ (4 mg/kg/day) in drinking water for 7 consecutive days. Rats of Group 3 were injected with a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). Animals in Group 4 were received TQ and DENA. DENA significantly increased alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and total nitrate/nitrite (NOx) and decreased reduced glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx), glutathione-s-transferase (GST) and catalase (CAT) activity in liver tissues. Moreover, DENA decreased gene expression of GSHPx, GST and CAT and caused severe histopathological lesions in liver tissue. Interestingly, TQ supplementation completely reversed the biochemical and histopathological changes induced by DENA to the control values. In conclusion, data from this study suggest that: (1) decreased mRNA expression of GSHPx, CAT and GST during DENA-induced initiation of hepatic carcinogenesis, (2) TQ supplementation prevents the development of DENA-induced initiation of liver cancer by decreasing oxidative stress and preserving both the activity and mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes.

Key words: diethylnitrosamine, thymoquinone, hepatic carcinogenesis, gene expression

Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world.1 The major risk factors in liver cancer includes hepatitis viral infection, food additives, alcohol, aflatoxins, environmental and industrial toxic chemicals, air and water pollutants.2,3 Diethylnitrosamine (DENA) is a well known hepatocarcinogenic agent present in tobacco smoke, water, cured and fried meals, cheddar cheese, agriculture chemicals and cosmetics and pharmaceutical products.4–6 DENA is known to induce liver cancer in experimental animal models through inhibition of many enzymes involved in DNA repair mechanism.7 In rats, DENA is a potent hepatocarcinogen influencing the initiation stage of carcinogenesis during a period of enhanced cell proliferation accompanied by hepatocellular necrosis and induces DNA carcinogen adducts, DNA-strand breaks and in turn hepatocellular carcinomas without cirrhosis through the development of putative preneoplastic focal lesions.8 Although there are many strategies for the treatment of liver cancer,9–11 its therapeutic outcome remains very poor. Therefore, prevention seems to be the best strategy for lowering the incidence of this disease. In this regard, many compounds have been tested and proved efficacy against experimentally- induced hepatocarcinogenesis including morin,12 silymarin, 13 garlic,14 star anise,15 ganfujian granule,1 apigenin16 and the crude extracts of agarcus blazei.17

Thymoquinone (TQ), the main constituents of the volatile oil from Nigella sativa seeds is reported to protect laboratory animals against chemical toxicity and induction of carcinogenesis. In this regard, earlier studies have demonstrated that TQ has a considerable protective effect against reactive oxygen species (ROS) generating agents including carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity,18 doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity19 and gentamicin-induced nephropathy.20 Several studies reported that TQ supplementation in drinking water resulted in significant suppression of forestomach tumor induced by benzo(α) pyrene21 and 2-methyclonathrene.22 Recently, Nagi et al.18 reported that oral administration of TQ is a promising prophylactic agent against chemical carcinogenesis and toxicity in liver tissues by increasing the activities of quinone reductase and glutathione transferase. Taken together, this prompted us to initiate this study to gain insights into the possibility of mechanism-based protection by TQ supplementation against DENA-induced initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis.

Results

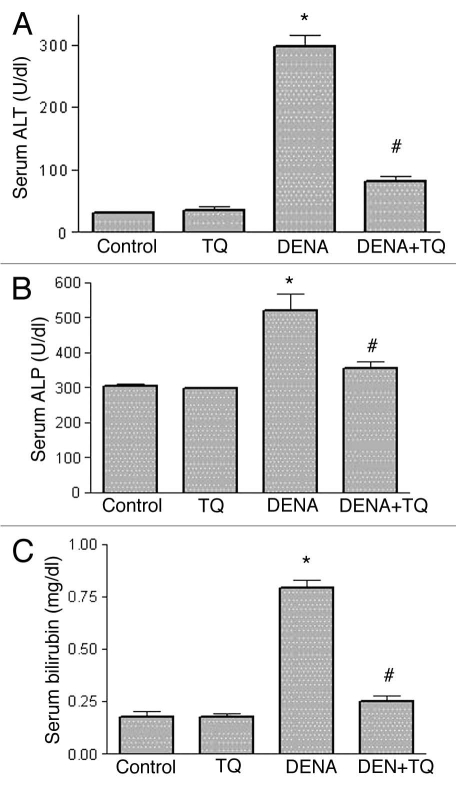

Figure 1 shows the effects of DENA, TQ and their combination on the indices of serum liver function, ALT (Fig. 1A), ALP (Fig. 1B) and total bilirubin (Fig. 1C). DENA resulted in a significant 858%, 71% and 364% increase in serum ALT, ALP and bilirubin, respectively, as compared to the control group. TQ supplementation alone for 7 days showed non-significant change. Interestingly, administration of TQ in combination with DENA resulted in a complete reversal of DENA-induced increase in serum ALT, ALP and bilirubin to the control values.

Figure 1.

Effects of diethylnitrosamine (DENA), thymoquinone (TQ) and their combination on the indices of serum liver function, alanine transaminase (ALT) (A), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (B) and total bilirubin (C). Rats were randomly divided into 4 different groups of 10 animals each: Control, TQ, DENA and TQ plus DENA. Initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis was induced by administration of a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). TQ (4 mg/kg/day) was supplemented in drinking water for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after DENA. Blood samples were drawn from the orbital venous plexus 48 hours after administration of DENA and serum ALT, ALP and total bilirubin were measured. Data are presented as the mean ± SE M. * and # indicate significant change from control and DENA, respectively, at p < 0.05 using ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer as a post ANOVA test.

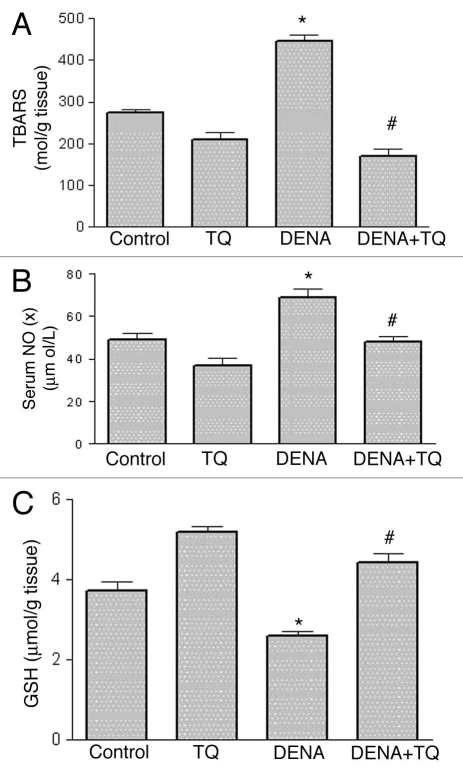

The effects of DENA, TQ and their combination on the oxidative and nitrosative stress biomarkers, TBARS (Fig. 2A), NOx (Fig. 2B) and GSH (Fig. 2C), in liver tissues are shown in Figure 2. DENA resulted in a significant 62 and 41% increase in TBARS and NOx, respectively and a significant 33% decrease in GSH as compared to the control group. Pretreatment with TQ resulted in a complete reversal of DENA-induced increase in TBARS and NOx and decrease in GSH in liver tissues to the control values.

Figure 2.

Effects of diethylnitrosamine (DENA), thymoquinone (TQ) and their combination on the oxidative and nitrosative stress biomarkers, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) (A), nitrate/nitrite (NOx) (B) and reduced glutathione (GSH ) (C). Rats were randomly divided into 4 different groups of 10 animals each: Control, TQ, DENA and TQ plus DENA. Initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis was induced by administration of a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). TQ (4 mg/kg/day) was supplemented in drinking water for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after DENA Nitrate/nitrite (NOx) was measured in serum, whereas TBARS and GSH were determined in liver tissue homogenates 48 hours after administration of DENA. Data are presented as the mean ± SE M. * and # indicate significant change from control and DENA, respectively, at p < 0.05 using ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer as a post ANOVA test.

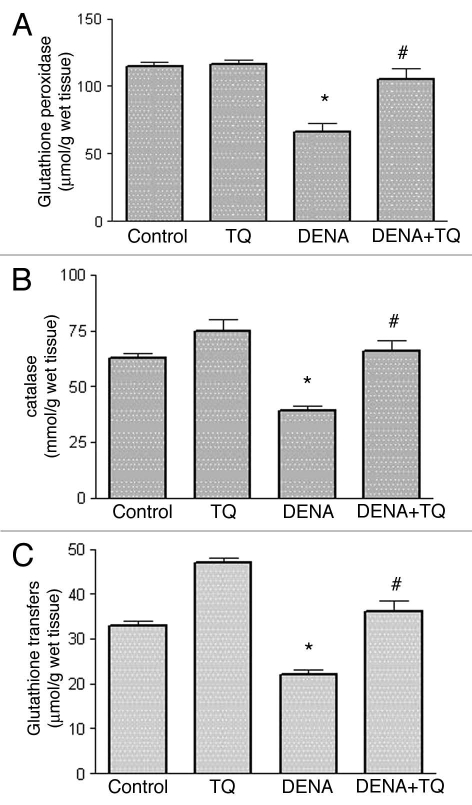

Figure 3 shows the effects of DENA on the activity of the antioxidant enzymes, GSHPx (Fig. 3C), CAT (Fig. 3C) and GST (Fig. 3C), in liver tissues from normal and TQ-supplemented rats. DENA resulted in a significant 43, 38 and 33% decrease in the activity of GSHPx, CAT and GST, respectively, as compared to the control group. In TQ supplemented rats, TQ resulted in a complete reversal of DENA-induced decrease in GSHPx, CAT and GST in liver tissues to the control values.

Figure 3.

Effects of diethylnitrosamine (DENA) on the activity of the antioxidant enzymes, glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx) (A), catalase (CAT) (B) and glutathione transferase (GST) (C), in liver tissues from normal and thymoquinone (TQ)-supplemented rats. Rats were randomly divided into 4 different groups of 10 animals each: Control, TQ, DENA and TQ plus DENA. Initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis was induced by administration of a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). TQ (4 mg/kg/day) was supplemented in drinking water for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after DENA. GSHPx, CAT and GST activities were determined in liver tissue homogenates 48 hours after administration of DENA. Data are presented as the mean ± SE M. * and # indicate significant change from control and DENA, respectively, at p < 0.05 using ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer as a post ANOVA test.

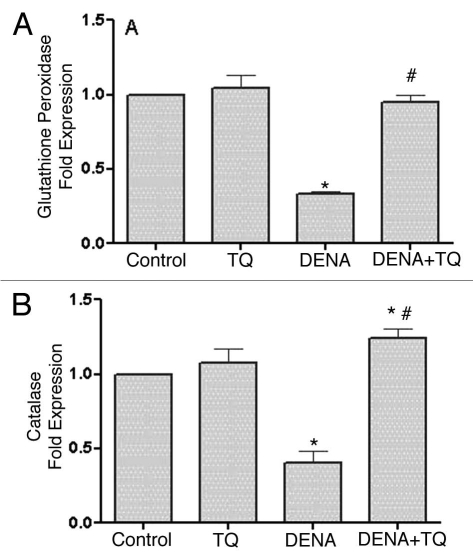

Figure 4 shows the effect of DENA on the mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes, GSHPx (Fig. 4A), CAT (Fig. 4B) and GST (Fig. 4C), in liver tissues of normal and TQ-supplemented rats. DENA resulted in a significant 32, 40 and 52% decrease in GSHPx, CAT and GST, respectively, as compared to the control group. On the other hand, TQ supplementation resulted in a complete reversal of DENA-induced decrease in mRNA expression of GSHPx, CAT and GST in liver tissues to the control values.

Figure 4.

Effects of diethylnitrosamine (DENA) on the mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes, glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx) (A), catalase (CAT) (B) and glutathione transferase (GST) (C), in liver tissues of normal and TQ-supplemented rats. Rats were randomly divided into 4 different groups of 10 animals each: Control, TQ, DENA and TQ plus DENA. Initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis was induced by administration of a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). TQ (4 mg/kg/day) was supplemented in drinking water for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after DENA. GSHPx, CAT and GST mRNA expression were determined in liver tissues 48 hours after administration of DENA. Data are presented as the mean ± SE M. * and # indicate significant change from control and DENA, respectively, at p < 0.05 using ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer as a post ANOVA test.

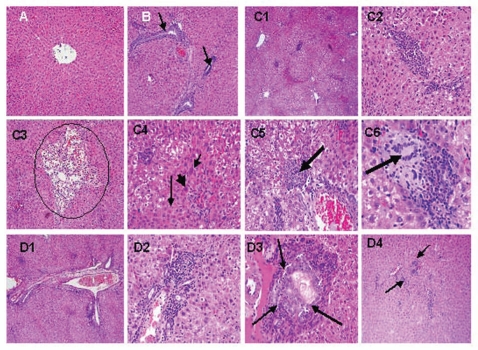

Figure 5 shows the histopathological changes in liver tissues induced by DENA in normal and TQ-supplemented rats. Liver from control rat showed normal liver histology with no signs of liver injury (total score: 2) manifested as normal hepatic nodules and central vein (Fig. 5A). Liver from rat treated with TQ alone showed no significant hepatic injury (total score: 3) manifested as areas with minimal vascular congestion and focal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, most of which are seen around bile ducts (Fig. 5B). Liver from rat treated with DENA alone showed clear signs of severe hepatic injury (total score: 14) manifested as area with periportal and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates with diffuse ballooning degeneration, intra-acinar lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear infiltrates with adjacent hepatocytes exhibiting feathery degeneration and regenerative cellular changes, proliferation of vascular channels are also noted in several areas, binucleation, acidophilic bodies and nuclear enlargement are some of the regenerative cellular changes noted in most of the sections, granuloma formation accompanied by hepatocytes exhibiting ballooning degeneration and multinucleated giant cells are seen, within some of the granulomas (Fig. 5C). Liver from rat treated with TQ plus DENA showed mild hepatic injury (total score: 6) manifested as periportal inflammation with conspicuously dilated blood vessels and ballooning degeneration, mononuclear infiltrates associated with regenerative cellular changes of the adjacent hepatocytes, mild bile duct proliferation and intra-acinar inflammatory cell infiltrates.

Figure 5.

Effects of diethylnitrosamine (DENA), thymoquinone (TQ) and their combination on histopathological changes in liver tissues. Rats were randomly divided into four different groups of 10 animals each: Control, TQ, DENA and TQ plus DENA. Initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis was induced by administration of a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). TQ (4 mg/kg/day) was supplemented in drinking water for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after DENA. Liver specimens from each group were removed to be examined histopathologically, they were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, sectioned at 3 µm and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E) stain for light microscopic examination. (A) Liver from control rat showing normal liver histology with normal hepatic nodules and central vein (X10). (B) Liver from rat treated with thymoquinone (TQ) showing areas with minimal vascular congestion and focal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, most of which are seen around bile ducts. (arrows, 10X). (C) Liver from rat treated with diethylnitrosamine (DENA) showing area with periportal and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, with diffuse ballooning degeneration. (C1, X10), intra-acinar lymphoplasmacytic and polymorphonuclear infiltrates, with adjacent hepatocytes exhibiting feathery degeneration and regenerative cellular changes (C2, X40), proliferation of vascular channels (circle) are also noted in several areas (C3, X10), binucleation (short thin arrow), acidophilic bodies (long thin arrow) and nuclear enlargement (thick arrow) are some of the regenerative cellular changes noted in most of the sections (C4, X40), granuloma formation (arrow) accompanied by hepatocytes exhibiting ballooning degeneration (C5, X20) and multinucleated giant cells (arrow) are seen, within some of the granulomas (C6, X40). (D) Liver from rat treated with thymoquinone (TQ) plus diethylnitrosamine (DENA) showing periportal inflammation with conspicuously dilated blood vessels and ballooning degeneration ((D1, X10), mononuclear infiltrates associated with regenerative cellular changes of the adjacent hepatocytes (D2, X40), mild bile duct proliferation (D3, 40X) and intra-acinar inflammatory cell infiltrates (D4, 10X).

Discussion

Chemoprevention is defined as the use of naturally occurring and/or synthetic compounds in cancer therapy in which the occurrence of cancer can be entirely prevented, slowed or reversed.13 Number of investigations are being conducted worldwide, to discover natural products that can suppress or prevent the process of carcinogenesis.23–26 Research on plants helped in the identification of compounds with anticancer activity from non-traditionally used plants that clinically used as useful drugs.27 The current study has been initiated to investigate whether TQ supplementation could inhibit the initiation stage of hepatic carcinogenesis induced by DENA in rats.

Data presented in the current study demonstrate that DENA increased serum indices of liver function including ALT, ALP and total bilirubin (Fig. 1) and caused severe histopathological lesions (total score: 14) in liver tissues (Fig. 5). It is well known that the elevation of ALT and ALP is credited to hepatocellular damage and reflects the pathological alteration in biliary flow.12,28 In the current study, this observed increase in serum indices of liver function by DENA could be a secondary event following DENA-induced lipid peroxidation of hepatocyte membranes with the consequent increase in the leakage of ALT, ALP and total bilirubin from liver tissues. An elevated level of serum indices of hepatocellular damage has been previously reported in many models of DENA-induced hepatocellular degeneration. 7,12,17,24,29 Fascinatingly, TQ supplementation prevented the increase in hepatic enzymes, suggesting that TQ may have potential protective effect against DENA-induced liver damage. This effect could be due to stabilization of hepatocyte membranes by TQ with the consequent decrease in the leakage of liver enzymes.

Catalase and GSHPx act as supporting antioxidant enzymes by converting hydrogen peroxide to water, thereby providing protection against reactive oxygen species.30 The reduction in activity of these enzymes may be caused by the increase in free radical production during DENA metabolism. Data from this study revealed that DENA significantly increased NOx and TBARS and decreased, GSHPx, CAT and GST activity and mRNA expression in liver tissues, suggesting that reactive oxygen and nitrogen species induced by DENA play an important role in DENAinduced initiation of hepatic carcinogenesis. The contribution of oxidative stress during development of hepatocarcinogenesis and promotion of liver cancer has been recently confirmed.31–36 Therefore, quenching lipid peroxidation and enhancing endogenous enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant status by chemopreventive compounds represent an effective strategy to prevent hepatocarcinogenesis.32–37 Increased oxidative stress biomarkers and depletion of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants have been reported in cancer patients and other human diseases.38,39 Glutathione peroxidase is endogenous antioxidant selenoprotein present in the cytosol and mitochondrial matrix that participates in the defense mechanism. It is generally activated before the initiation of chronic oxidative stress and catalyzes the reduction of lipid and non-lipid hydroperoxides using two molecules of GSH and thereby curtails the quantity of biomolecules having destructive properties.40 Similarly, GST is a soluble protein located in cytosol and plays an important role in detoxification and excretion of xenobiotics.7 Induction of xenobiotic detoxifying enzymes is an additional mechanism by which antioxidant rich extracts may act as anticarcinogens as they compete with steps in xenobiotic activation and metabolize toxic compounds to non-toxic ones.41 As the activity of GST increased in TQ-treated rats, it appears that TQ induces greater coupling of electrophilic intermediates with GSH. Increased generation of reactive oxygen species and decreased antioxidant enzymes in liver tissues has been reported in many models of DENA-induced hepatocellular carcinoma.12–15 It has been reported that reactive oxygen species play a major role in tumor promotion through interaction with the critical macromolecules including lipids, DNA and DNA repair systems.42 Moreover, NOx is known to inhibit DNA repair proteins, thereby inhibiting the ability of the cell to repair damaged DNA.43,44 Treatment of rats with TQ resulted in upregulation of the GSHPx, CAT and GST genes with the consequent elevation of hepatic GSHPx, CAT and GST levels to overcome oxidative stress induced during DENA metabolism. Our results are consistent with recent studies which have demonstrated that TQ supplementation increases the expression of antioxidant genes, GSHPx, CAT and GST, in rat liver and induces quinone reductase in mice liver which may protect against chemical carcinogenesis and toxicity.41,45

Methods

Animals.

Adult male Wistar albino rats, weighing 180–200 g, were obtained from the Experimental Animal Care Center, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University (KSU), Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and were housed in metabolic cages under controlled environmental conditions (25°C and a 12 h light/dark cycle). Animals had free access to pulverized standard rat pellet food and tap water unless otherwise indicated. The protocol of this study has been approved by Research Ethics Committee of College of Pharmacy, KSU, Riyadh, KSA.

Materials.

Diethylnitrosamine (DENA) and Thymoquinone (TQ) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., (St. Louis, MO). DENA was dissolved in saline and injected in a single dose (200 mg/kg, I.P.) to initiate hepatic carcinogenesis. TQ was given in drinking water (50 mg/L) for 7 consecutive days. The calculated doses of TQ, based on the average daily water intake, were 4 mg/kg/day according to Badary et al.46 All other chemicals used were of the highest analytical grade.

Experimental design.

In the current study, the dose of DENA and the time required to study initiation stage of hepatic carcinogenesis in rats were adopted from Barbisan et al.17 To achieve the ultimate goal of this study, a total of 40 adult male Wistar albino rats were divided into four groups of 10 animals each. Rats of Group 1 (control group) received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of normal saline (2.5 ml/kg) for 7 consecutive days. Animals in Group 2 (TQ-supplemented) were given TQ (4 mg/kg/day) in drinking water for 7 consecutive days. Rats of Group 3 (DENA group) were injected with the same doses of normal saline for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). Animals in Group 4 (TQ supplemented-DENA group) were received the same doses of TQ for 5 consecutive days before and 2 days after a single dose of DENA (200 mg/kg, I.P.). Forty-eight hours after administration of DENA, animals were anesthetized with ether and blood samples were drawn from the orbital venous plexus. Serum was separated by centrifugation for 5 min at 1,500 g and stored at −20°C until analysis. This was used for the determination of ALT, ALP activities, total bilirubin and total nitrate/nitrite (NOx). All animals were then sacrificed by decapitation and their livers were rapidly excised, weighed, washed with saline, blotted with a piece of filter paper and homogenized in normal saline to yield a 10% (w/v) tissue homogenate, using a Branson sonifier (250 VWR Scientific, Danbury, CT). Liver specimens from each group were removed to be examined histopathologically, they were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, sectioned at 3 µm and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E) stain for light microscopic examination.

Histopathological examination of liver tissues.

To avoid any type of bias, the slides were coded and examined by a histopathologist who was blinded to the treatment groups. Grading of injury was according to the following parameters: (1) Degeneration and intracellular accumulation (% of liver parenchyma involvement with ballooning degeneration, feathery degeneration, swelling of hepatocytes and steatosis): None = 0, <25% of the liver parenchyma involved = +1, 25–50% of the liver parenchyma involved = +2, 50–75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +3 and >75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +4; (2) Necrosis and apoptosis (ischemic coagulation necrosis, centrilobular necrosis and apoptotic cell death: None = 0, <25% of the liver parenchyma involved = +1, 25–50% of the liver parenchyma involved = +2, 50–75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +3 and >75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +4 (3) Inflammation (injury to the liver associated with an influx of acute or chronic inflammatory cells (usually periportal): None = 0, one focus of periportal inflammation per section = +1, 2–4 foci of periportal inflammation per section = +2, 5 or more foci of periportal inflammation with concomitant interstitial inflammation = +3; (4) Regeneration (mitosis and thickening of hepatocyte cords): None = 0, <25% of the liver parenchyma involved = +1, 25–50% of the liver parenchyma involved = +2, 50–75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +3, >75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +4; (5) Fibrosis (proliferation of dense fibrous connective tissue, usually seen surrounding liver lobules, associated with disruption of normal liver architecture): None = 0, <25% of the liver parenchyma involved = +1, 25–50% of the liver parenchyma involved = +2, 50–75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +3, >75% of the liver parenchyma involved = +4. The scoring system used was according to the following scale: (A) No hepatotoxicity: 0–3, (B) Mild hepatotoxicity: 4–8, (C) Moderate hepatotoxicity: 9–13, (D) Severe hepatotoxicity: 14–19.

Measurements of liver function.

The activities of ALT and ALP as well as total bilirubin in serum were determined using Randox commercially available kits (Randox Laboratories Ltd., Diamond Road, Crumlin, Co., Antrim, UK).

Determination of reduced glutathione and lipid peroxidation in liver tissues.

The tissue levels of the acid soluble thiols, mainly GSH, were assayed spectrophotometrically at 412 nm, according to the method of Ellman,47 using a Shimadzu (Tokyo, Japan) spectrophotometer. The contents of GSH were expressed as mmol/g wet tissue. The degree of lipid peroxidation in liver tissues was determined by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in the supernatant tissue from homogenate Ohkawa et al.48 The homogenates were centrifuged at 1,500 g and supernatant was collected and used for the estimation of TBARS. The absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm and the concentrations were expressed as nmol TBARS/g wet tissue.

Determination of total nitrate/nitrite concentrations in serum.

Total nitrate/nitrite (NOx), an index of nitric oxide (NO) production, was measured as stable end product, nitrite, according to the method of Miranda et al.49 The assay is based on the reduction of nitrate by vanadium trichloride combined with detection by the acidic griess reaction. The diazotization of sulfanilic acid with nitrite at acidic pH and subsequent coupling with N-(10 naphthyl)-ethylenediamine produced an intensely colored product that is measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm.

Determination of glutathione peroxidase, catalase and glutathione transferase activity and mRNA expression in liver tissues.

The activity of glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx) was determined according to the method of Lawrence and Burk,50 The changes in the absorbance at 340 nm were recorded at 1 min interval for 5 min and the results were expressed as µmol/min/g tissue. The catalase (CAT) activity was determined spectrophotometrically by the method of Higgins et al.51 which is the assay of hydrogen peroxide. The activity was expressed as µmol/min/g tissue using the molar absorbance of 43.6 for hydrogen peroxide. Glutathione transeferase activity was assayed as previously described by Habig et al.52 using 1-chloro-2, 4-dinitrobenzene and the results were expressed as nmol/min/mg protein.

Total RNA extraction.

The expression of glutathione peroxidase, catalase and glutathione transferase was determined by real rime PCR Applied biosystem. Total RNA were extracted from liver tissue by Trizol method according to the standard protocol as previously described by Chomczynski.53 In Brief, RNA was extracted by homogenization (Polytron; Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland) in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) at maximum speed for 90–120 s. The homogenate was incubated for 5 min at room temperature. A 1:5 volume of chloroform was added, and the tube was vortexes and subjected to centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min. The aqueous phase was isolated, and one-half of the volume of isopropanol was added to precipitate the RNA. After centrifugation and washing the total RNA was finally eluted in DEPC-treated H2O, and the quantity and integrity were characterized using a UV spectrophotometer (UVmini1240 SHIMADZU). RNA was electrophoresed on ethidium bromide stained agarose gel. The isolated RNA has an A 260/280 ratio of 1.9–2.1.

First-strand cDNA synthesis using superScript II RT.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA by reverse transcription with a SuperScript™ first-strand synthesis system kit (Invitrogen, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

EVAgreen polymerase chain reaction.

The genes levels were measured using qPCR GreenMaster with UNG/ROX (Jena Bioscience, Germany) with EvaGreen dye and the 2-ΔΔCt method. We used GAPDH gene as the housekeeping gene. Briefly, a standard 25 µl reaction mixture contained in final concentration of 1x AMV/TF1 reaction buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs mix, 3 mM MgSO4, 0.1 U AMV reverse transcriptase, 0.1 U Tf1 DNA polymerase, 0.8 U RNase inhibitor (Jena Bioscience Germany), 0.5 µM of each reverse and forward primers GPX R. AGA GCG GGT GAG CCT TCT and F. GGG CAA AGA AGA TTC CAG GTT, GHST R. GTC AGC CTG TTC CCT ACA AG and F. GCC TTC TAC CCG AAG ACA CCT T and CAT R. GTA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG ACA CGA GGT CCC AGT TAC CAT and F. AGG TGA CAC TAT AGA ATA GTG GTT TTC ACC GAC GAG AT (Jena Bioscience, Germany), 100 ng of cDNA and RNase free water. Target genes were amplified in low-profile 0.2 ml tube stripes (Axygen, CA). The amplification was performed in Applied biosystem (Applied biosystem, USA). No template control (NTC) was used as a negative control. The cycling programme consists of pre-denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing/extension temperature at 60°C for 1 min. Finally, a melting curve analysis was undertaken from 60 to 95°C. The real time PCR yields a value (Ct) having the threshold cycle of specific target gene amplification at which the PCR products are first detected via flouorescence.

Melting curve and agarose gel electrophoresis analysis.

Following amplification, melting curve analysis was performed to verify the correct product according to its specific melting temperature (Tm). The melting curve analysis software of applied biosystem analyzed the results. Amplification plots and Tm values were routinely analyzed to confirm the specificities of the amplicons for EvaGreen PCR amplification. Agarose gel electrophoresis for analyzing the product of GAPDH, Catalase, Glutathione S transferase and Glutathione peroxidase amplification indicates the existence of a single band for each gene.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between obtained values (mean ± SEM, n = 10) were carried out by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. A p value of 0.05 or less was taken as a criterion for a statistically sig.

Conclusions

Data from this study suggest that: (1) decreased mRNA expression of GSHPx, CAT and GST during DENA-induced initiation of hepatic carcinogenesis, (2) TQ supplementation prevents the development of DENA-induced initiation of liver cancer by a mechanism related, at least in part, to the ability of TQ to decrease oxidative stress and preserve the activity and expression of antioxidant enzymes. This will open new perspectives for the use of TQ alone or in combination with other natural chemopreventive compounds to prevent, slow or reverse the occurrence of liver cancer.

Acknowledgements

The present work was supported by operating grant from Research Center, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University (CPRC 232).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oximed/article/12714

References

- 1.Qian Y, Ling CQ. Preventive effect of Ganfujian granule on experimental hepatocarcinoma in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:755–757. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farazi PA, Depinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JL. N-Nitrosamines. Occup Med. 1999;14:839–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ, Stershic MT, Keefer Lk. Acceleration of N-nitrosation reactions by electrophiles. IARC Sci Publ. 1991:370–374. doi: 10.1002/chin.199210322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reh BD, Fajen JM. Worker exposures to nitrosamines in a rubber vehicle sealing plant. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1996;57:918–923. doi: 10.1080/15428119691014431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansal AK, Bansal M, Soni G, Bhatnagar D. Protective role of Vitamin E pre-treatment on N-nitrosodiethylamine induced oxidative stress in rat liver. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;156:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tatematsu M, Mera Y, Inoue T, Satoh K, Sato K, Ito N. Stable phenotypic expression of glutathione S-transferase placental type and unstable phenotypic expression of gamma-glutamyltransferase in rat liver preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:215–220. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu PC, Buxton JA, Tu AW, Hill WD, Yu A, Krajden M. Publicly funded pegylated interferon-alpha treatment in British Columbia: disparities in treatment patterns for people with hepatitis C. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:359–364. doi: 10.1155/2008/243607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemoine A, Azoulay D, Jezequel-Cuer M, Debuire B. [Hepatocellular carcinoma] Pathol Biol. 1999;47:903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young KJ, Lee PN. Intervention studies on cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8:91–103. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivaramakrishnan V, Shilpa PN, Praveen Kumar VR, Niranjali Devaraj S. Attenuation of N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocellular carcinogenesis by a novel flavonol-Morin. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;171:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramakrishnan G, Raghavendran HR, Vinodhkumar R, Devaki T. Suppression of N-nitrosodiethylamine induced hepatocarcinogenesis by silymarin in rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;161:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kweon S, Park KA, Choi H. Chemopreventive effect of garlic powder diet in diethylnitrosamine-induced rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Life Sci. 2003;73:2515–2526. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00660-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav AS, Bhatnagar D. Chemo-preventive effect of Star anise in N-nitrosodiethylamine initiated and phenobarbital promoted hepato-carcinogenesis. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;169:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh JP, Selvendiran K, Banu SM, Padmavathi R, Sakthisekaran D. Protective role of Apigenin on the status of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defense against hepatocarcinogenesis in Wistar albino rats. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:309–314. doi: 10.1078/0944711041495254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbisan LF, Scolastici C, Miyamoto M, Salvadori DM, Ribeiro LR, Da Eira AF, et al. Camargo. Effects of crude extracts of Agaricus blazei on DNA damage and on rat liver carcinogenesis induced by diethylnitrosamine. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2:295–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagi MN, Alam K, Badary OA, Al-Shabanah OA, Al-Sawaf HA, Al-Bekairi AM. Thymoquinone protects against carbon tetrachloride hepatotoxicity in mice via an antioxidant mechanism. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1999;47:153–159. doi: 10.1080/15216549900201153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagi MN, Mansour MA. Protective effect of thymoquinone against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats: a possible mechanism of protection. Pharmacol Res. 2000;41:283–289. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayed-Ahmed MM, Nagi MN. Thymoquinone supplementation prevents the development of gentamicin-induced acute renal toxicity in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:399–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badary OA, Al-Shabanah OA, Nagi MN, Al-Rikabi AC, Elmazar MM. Inhibition of benzo(a)pyrene-induced forestomach carcinogenesis in mice by thymoquinone. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8:435–440. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badary OA, Gamal El-Din AM. Inhibitory effects of thymoquinone against 20-methylcholanthrene-induced fibrosarcoma tumorigenesis. Cancer Detect Prev. 2001;25:362–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manthey JA, Guthrie N. Antiproliferative activities of citrus flavonoids against six human cancer cell lines. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5837–5843. doi: 10.1021/jf020121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SM, Li ML, Tse YC, Leung SC, Lee MM, Tsui SK, et al. Radix, a Chinese herbal extract, inhibit hepatoma cells growth by inducing apoptosis in a p53 independent pathway. Life Sci. 2002;71:2267–2277. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal BB, Kumar A, Bharti AC. Anticancer potential of curcumin: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:363–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng YL, Chang WL, Lee SC, Liu YG, Chen CJ, Lin SZ, et al. Acetone extract of Angelica sinensis inhibits proliferation of human cancer cells via inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Life Sci. 2004;75:1579–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinghorn AD, Su BN, Jang DS, Chang LC, Lee D, Gu JQ, et al. Natural inhibitors of carcinogenesis. Planta Med. 2004;70:691–705. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulle F, Mavier P, Zafrani ES, Preaux AM, Lescs MC, Siegrist S, et al. Mechanism of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase release in serum during intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholestasis in the rat: a histochemical, biochemical and molecular approach. Hepatology. 1990;11:545–550. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha WS, Kim CK, Song SH, Kang CB. Study on mechanism of multistep hepatotumorigenesis in rat: development of hepatotumorigenesis. J Vet Sci. 2001;2:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasquez-Garzon VR, Arellanes-Robledo J, Garcia-Roman R, Aparicio-Rautista DI, Villa-Trevino S. Inhibition of reactive oxygen species and pre-neoplastic lesions by quercetin through an antioxidant defense mechanism. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:128–137. doi: 10.1080/10715760802626535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gayathri R, Priya DK, Gunassekaran GR, Sakthisekaran D. Ursolic acid attenuates oxidative stress-mediated hepatocellular carcinoma induction by diethylnitrosamine in male Wistar rats. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:933–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Rejaie SS, Aleisa AM, Al-Yahya AA, Bakheet SA, Alsheikh A, Fatani AG, et al. Progression of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic carcinogenesis in carnitinedepleted rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1373–1380. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taha MM, Abdul AB, Abdullah R, Ibrahim TA, Abdelwahab SI, Mohan S. Potential chemoprevention of diethylnitrosamine-initiated and 2-acetylaminofluorene-promoted hepatocarcinogenesis by zerumbone from the rhizomes of the subtropical ginger (Zingiber zerumbet) Chem Biol Interact. 2010;186:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizukami S, Ichimura R, Kemmochi S, Wang L, Taniai E, Mitsumori K, et al. Tumor promotion by copper-overloading and its enhancement by excess iron accumulation involving oxidative stress responses in the early stage of a rat two-stage hepatocarcinogenesis model. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;185:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janani P, Sivakumari K, Geetha A, Ravisankar B, Parthasarathy CJ. Chemopreventive effect of bacoside A on N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:759–770. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0715-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang L, Dong W, Yan F, Ren X, Hao X. Recombinant bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor protects the liver from carbon tetrachloride-induced acute injury in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;62:332–338. doi: 10.1211/jpp.62.03.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darvesh AS, Bishayee A. Selenium in the prevention and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10:338–345. doi: 10.2174/187152010791162252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta A, Bhatt ML, Misra MK. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oxid med Cell Longev. 2009;2:68–72. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.2.8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher-Wellman K, Bell HK, Bloomer RJ. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanisms linked to exercise during cardiopulmonary and metabolic disorders. Oxid med Cell Longev. 2009;1:43–51. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.1.7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh BN, Singh BR, Sarma BK, Singh HB. Potential chemoprevention of N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis by polyphenolics from Acacia nilotica bark. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;181:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ismail M, Al-Naqeep G, Chan KW. Nigella sativa thymoquinone-rich fraction greatly improves plasma antioxidant capacity and expression of antioxidant genes in hypercholesterolemic rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michiels C, Raes M, Toussaint O, Remacle J. Importance of Se-glutathione peroxidase, catalase and Cu/Zn-SOD for cell survival against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wink DA, Cook JA, Christodoulou D, Krishna MC, Pacelli R, Kim S, et al. Nitric oxide and some nitric oxide donor compounds enhance the cytotoxicity of cisplatin. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:88–94. doi: 10.1006/niox.1996.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe KI, Hess A, Bloch W, Michel O. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitor suppresses the ototoxic side effect of cisplatin in guinea pigs. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:401–406. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200006000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagi MN, Almakki HA. Thymoquinone supplementation induces quinone reductase and glutathione transferase in mice liver: possible role in protection against chemical carcinogenesis and toxicity. Phytother Res. 2009;23:1295–1298. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badary OA, Nagi MN, Al-Shabanah OA, Al-Sawaf HA, Al-Sohaibani MO, Al-Bekairi AM. Thymoquinone ameliorates the nephrotoxicity induced by cisplatin in rodents and potentiates its antitumor activity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:1356–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawrence RA, Burk RF. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:952–958. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins CP, Baehner RL, Mccallister J, Boxer LA. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte species differences in the disposal of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1978;158:478–481. doi: 10.3181/00379727-158-40230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Habig WH, PabstM I, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7130–7139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chomczynski P. A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechniques. 1993;15:532–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]