Abstract

Carbon monoxide (CO) plays a significant role in vascular functions. We here examined the molecular mechanism by which CO regulates HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1)-dependent expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is an important angiogenic factor. We found that astrocytes stimulated with CORM-2 (CO-releasing molecule) promoted angiogenesis by increasing VEGF expression and secretion. CORM-2 also induced HO-1 (hemeoxygenase-1) expression and increased nuclear HIF-1α protein level, without altering its promoter activity and mRNA level. VEGF expression was inhibited by treatment with HIF-1α siRNA and a hemeoxygenase inhibitor, indicating that CO stimulates VEGF expression via up-regulation of HIF-1α protein level, which is partially associated with HO-1 induction. CORM-2 activated the translational regulatory proteins p70S6k and eIF-4E as well as phosphorylating their upstream signal mediators Akt and ERK. These translational signal events and HIF-1α protein level were suppressed by inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), MEK, and mTOR, suggesting that the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways are involved in a translational increase in HIF-1α. In addition, CORM-2 also increased stability of the HIF-1α protein by suppressing its ubiquitination, without altering the proline hydroxylase-dependent HIF-1α degradation pathway. CORM-2 increased HIF-1α/HSP90α interaction, which is responsible for HIF-1α stabilization, and HSP90-specific inhibitors decreased this interaction, HIF-1α protein level, and VEGF expression. Furthermore, HSP90α knockdown suppressed CORM-2-induced increases in HIF-1α and VEGF protein levels. These results suggest that CO stimulates VEGF production by increasing HIF-1α protein level via two distinct mechanisms, translational stimulation and protein stabilization of HIF-1α.

Keywords: Akt PKB, ERK, Protein degradation, Translation, Ubiquitination, Carbon Monoxide (CO), Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90), Heme Oxygenase (HO), Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) alpha, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

Introduction

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a diffusible gas that has recently been found to play an important role in several biological processes, including angiogenesis and cytoprotection (1–4). CO is the product of the breakdown of heme by heme oxygenase (HO)2 enzymes (5). There are two heme oxygenase functional isoforms: an inducible form, HO-1, and a constitutive form, HO-2. CO produced from heme by the catalytic reaction of HO induces the synthesis of angiogenic mediators, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), IL-8, and stromal cell-derived factor-1, as well as decreasing the anti-angiogenic factors, namely soluble VEGF receptor-1 and soluble endoglin, resulting in the promotion of endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and anti-apoptotic responses (6–9). In addition, glutamate-induced CO in astrocytes can act as a signal or regulatory molecule that contributes to the homeostatic regulation of vascular functions such as vasodilation (10, 11).

HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor) is a transcriptional complex involved in the regulation of crucial aspects of cellular functions, such as cell proliferation, survival, invasion, and glucose metabolism (12, 13). HIF-1 is composed of two subunits, an oxygen-sensitive subunit, HIF-1α, and an oxygen-insensitive subunit, HIF-1β (14). Although HIF-1α protein level is mainly regulated by an oxygen-dependent mechanism, its protein level can also be controlled in an oxygen-independent fashion. A major oxygen-dependent regulatory mechanism is the proline hydroxylation of HIF-1α by proline hydroxylase (PHD) (15). Under normoxic conditions, two proline residues (Pro-402 and Pro-564) within the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODD) of HIF-1α are hydroxylated by PHD, which triggers binding of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL) and ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation (16–18). Under hypoxic conditions, however, PHD is inactivated, resulting in HIF-1α stabilization. The oxygen-independent regulation of HIF-1α level is based on the stimulation of HIF-1α protein synthesis through activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and MEK/ERK pathways (19). HIF-1α protein stability is also regulated in an oxygen-independent manner by the competitive binding of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), an ATPase-dependent molecular chaperone that controls folding, activation, and stabilization of several substrate proteins, including HIF-1α (20, 21). Stabilized HIF-1 translocates to the nucleus and binds to hypoxia response elements of several target genes, such as VEGF, metabolic enzymes, and erythropoietin, which are involved in the modulation of angiogenesis, ATP synthesis, oxygen supply, and cell survival (22–25).

Recent studies show that CO promotes angiogenesis via several mechanisms, including VEGF expression and IL-8 production (6, 9); however, the regulatory mechanism by which CO promotes HIF-1α activation has not been clearly elucidated at the molecular level. In this study, we investigated the effect of CO on HIF-1α protein level and VEGF expression as well as its molecular mechanism in astrocytes. We found that CO increases HIF-1α level by two distinct mechanisms, up-regulation of protein synthesis by activating the translational regulatory proteins p70 S6 kinase and eIF-4E through PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways and inhibition of HIF-1α degradation by promoting the interaction of HIF-1α with HSP90α. Thus, the CO-induced increase in HIF-1α protein level in astrocytes promoted the secretion of VEGF and the subsequent activation of adjacent and surrounding endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis. These results suggest that CO stimulates angiogenesis in a paracrine mode of action by increasing HIF-1α-mediated VEGF production in astrocytes via protein synthesis and stabilization of HIF-1α.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

MG132, rapamycin, PD98059, LY294002, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG), and proteinase inhibitor mixture were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD Chemicals). RuCl3, CORM-2 (CO-releasing molecule-2; (Ru(CO)3Cl2)2), hemin, actinomycin D (ActD), cycloheximide (CHx), deguelin, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) were purchased from Sigma. Sn(IV) protoporphyrin IX dichloride (SnPP) was purchased from Frontier Scientific.

Cell Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated from human umbilical cord veins by collagenase treatment as described previously (26) and used in passages 3–8. HUVECs were grown in M199 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Millipore), and 10 units/ml heparin (Sigma). Primary human brain astrocytes dissociated from normal human brain cortex tissue were purchased from the Applied Cell Biology Research Institute (Kirkland, WA). Primary astrocytes were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone) and used in passages 5–9. For hypoxia experiments, cells were incubated in a hypoxic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI) that maintained the cells under low oxygen tension (5% CO2 with 1% O2, balanced with N2).

Promoter Vector Construction and Luciferase Assay

The human HIF-1α (NM_001530) promoter (1202 bases) was produced by genomic PCR from human astrocyte cells. Primers used were 5′-CGGGGTACCTAGCTTGCAAAGTTGCCAAAGGCC-3′ (forward includes enzyme digestion sites for KpnI) and 5′-CCCAAGCTTGGTGAATCGGTCCCCGCGATG-3′ (reverse; for HindIII). The product was inserted into pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI). Astrocytes were transfected with a plasmid for pHIF-1α. Luciferase activity was assayed using the luciferase assay system (Promega). The relative luciferase units were normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

HO Activity Assay

HO enzyme activity in astrocyte microsomes was measured by bilirubin generation as described previously (27). Human astrocytes were pretreated with or without 50 μm SnPP for 15 min, followed by treatment with DMSO or 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. The cells were detached using trypsin/EDTA and centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was suspended in MgCl2 (2 mm) phosphate (100 mm) buffer (pH 7.4), lysed by three cycles of freezing and thawing, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was added to a reaction mixture containing NADPH (0.8 mm), mouse liver cytosol (2 mg) as a source of biliverdin reductase, the substrate hemin (10 μm), glucose 6-phosphate (2 mm), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (0.2 units) in a final volume of 400 μl. The reaction was performed in the dark for 1 h at 37 °C, and the formed bilirubin was extracted with chloroform (400 μl) and calculated by the difference in absorbance between 464 and 530 nm using the extinction coefficient of 40 mm−1 cm−1 for bilirubin. HO activity is expressed as pmol of bilirubin formed/mg of protein/h.

Transient Transfection and Conditioned Medium Preparation

Astrocytes were transiently transfected with HO-1 vector (provided by Dr. Jozef Dulak, Jagiellonian University) or with pcDNA3.1/HIF-1α vector or pcDNA3.1/HIF-1α DM vector (provided by Dr. Gregg L. Semenza, The Johns Hopkins University) using Lipofectamine and Plus reagent (Invitrogen). All transfections were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. After a 48-h transfection, cells were collected. For preparation of conditioned medium (CM), cells were cultured with serum-free DMEM for different time periods, and CM was collected and concentrated through a centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Beverly, MA). Protein levels of CM were determined by Western blot analysis. For preparation of CM for endothelial cell migration, cells were cultured with M199 containing 5% FBS, and CM was collected and concentrated (3×) through a centrifugal filter device (3 kDa cut-off; Millipore).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Human astrocytes were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, washed gently, blocked, and incubated with the HIF-1α primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor antibody (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained using DAPI (Molecular Probes). Images were obtained with a confocal microscope (Olympus FV300).

Extraction of Nuclear Proteins

Nuclear proteins were extracted as follows. Human astrocytes were incubated with RuCl3 or CORM-2 for 8 h and then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were scraped into buffer A (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.1 mm EDTA, 10 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EGTA) and centrifuged briefly. The cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A plus 0.1% Nonidet P-40. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min, the nuclear pellet was resuspended in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9) containing 0.4 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm EGTA and lysed by three cycles of freezing and thawing. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the nuclear lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was obtained, and the protein concentrations were measured using a Coomassie Protein Assay kit (Pierce).

Western Blot Analysis

Cellular proteins from transfected astrocytes and secreted proteins in conditioned medium were analyzed by Western blot. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (28). We used antibodies specific for HIF-1α (BD Biosciences), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (EMD Chemicals, NJ), HO-1 (Stressgen, Ann Arbor, MI), phospho-p70S6K, p70S6K, phospho-ERK, ERK, phospho-AKT, AKT, phospho-eIF-4E, eIF-4E (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), HSP90 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), VEGF (Thermo Scientific or Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), ubiquitin (Invitrogen), or actin (Sigma).

Immunoprecipitation

Cellular proteins from astrocytes were incubated with an antibody for HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals) or HSP90 (Stressgen or Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) in TEG buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, containing 150 mm NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100) with constant rotation overnight at 4 °C. Immune complexes were collected by centrifugation following incubation with protein G-Sepharose and washed three times with TEG buffer. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blot using the indicated antibodies.

RNA Interference

Oligonucleotides of human HIF-1α-specific siRNAs and the control non-silencing RNA were designed by Dharmacon Inc. The sequence of human HIF-1α siRNA was 5′-CTGGACACAGTGTGTTTGA-3′. The human HO-1 siRNA was purchased from Sigma (sc-44306), and the human HSP90α siRNA was purchased from Dharmacon (siGENOME SMART pool M-005186-02). Astrocytes were grown to 70% confluence, and siRNA was transfected into the cells using Lipofectamine and Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PHD Activity Assay

Human astrocytes were lysed in HEB buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2) containing protease inhibitor mixtures. [35S]Methionine-labeled VHL protein was synthesized by in vitro transcription and translation using pcDNA3.1/hygro-VHL plasmid, according to the instruction manual (Promega). GST-ODD (amino acids 401–603 of human HIF-1α) was purified from cell lysate of Escherichia coli transfected with pGEX-4T-1/HIF-1α-ODD plasmid. Resin-bound GST-ODD (200 μg of protein/∼80 μl of resin volume) was incubated in the presence of 2 mm ascorbic acid, 100 μm FeCl2, and 5 mm α-ketoglutarate with the indicated amounts of enzyme in 200 μl of NETN buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) with mild agitation for 90 min at 30 °C. The reaction mixture was centrifuged and washed three times with 10 volumes of NETN buffer. Resin-bound GST-ODD was mixed with 10 μl of 35S-labeled VHL in 500 μl of EBC buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mm NaCl, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40). After mild agitation at 4 °C for 2 h, the resin was washed three times with 1 ml of NETN buffer, and proteins were eluted in SDS sample buffer, fractionated by 12% SDS-PAGE, and detected by autoradiography. The amount of each sample loaded was monitored by staining the GST-ODD with Coomassie Blue.

RT-PCR

Total RNAs were isolated from the indicated cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RT-PCR analysis was performed as described previously (29). The following sets of primers were used: 5′-AGTCGGACAGCCTCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCTGCCTTGTATAGGA-3′ (reverse) for human HIF-1α; 5′-CAGGCAGAGAATGCTGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTTCACATAGCGCTGCA-3′ (reverse) for human HO-1; 5′-GAGAATTCGGCCTCCGAAACCATGAACTTTCTGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGCATGCCCTCCTGCCCGGCTCACCGC-3′ (reverse) for VEGF; 5′-CAGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TAGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′ (reverse) for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). PCR products were analyzed on 1.2% agarose gels, and the gels were digitally imaged (BioImaging System).

Polysome Assay

Polysome analysis was performed as described previously (30). Human astrocytes were lysed in 400 μl of lysis buffer (0.3 m NaCl, 15 mm MgCl2, 15 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide, 200 units of Superase-In (Ambion, Foster City, CA)). After centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 5 min, heparin (a broad range RNase inhibitor) was added to the supernatant and made up to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. After debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, the cytoxolic supernatants were laid on a 20–50% sucrose gradient (total volume, 5 ml) and centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 120 min in a Beckman SW-55Ti rotor at 4 °C. Fractions (0.2 ml) were collected and monitored for absorbance at the 254-nm wavelength. Each absorbance was calculated by subtracting the absorbance from blank-containing lysis buffer laid on a sucrose gradient. For RNA isolation from fractions (1.2 ml), samples were precipitated with an equal volume of isopropyl alcohol at −80 °C overnight and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. After precipitants were washed with 85% ethanol, pellets were resuspended in 40 μl of Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0) and precipitated by adding 4 μl of 3 m sodium acetate (pH 5.3) and 100 μl of 100% ethanol. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) water, added to 100 μl of Tris-buffered phenol/chloroform, and mixed well. Samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min, and the aqueous (upper) phase was transferred to a new tube. Then, lithium chloride (LiCl) was added to a final concentration of 2 m to remove heparin, a potent RT-PCR inhibitor. After incubation at −20 °C overnight and centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min, pellets were washed with 75% ethanol. Precipitants were resuspended in 20 μl of DEPC water and precipitated by adding 2 μl of 3 m sodium acetate (pH 5.3) and 60 μl of 100% ethanol. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min and washed with 75% ethanol. After all ethanol was removed, samples were resuspended in 10 μl of DEPC water and analyzed by RT-PCR using HIF-1α and GAPDH primers.

Cell Migration Assay

For a migration assay using the co-culture system, astrocytes were seeded on 24-well plates and cultured until reaching 90% confluence. Cells were pretreated with several chemical inhibitors for 30 min and incubated with 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. Media were removed and replaced with M199 containing 5% FBS for 20 h. The chemotactic motility of HUVECs was measured using Transwell plates (6.5-mm diameter, 8.0-μm pore size). The lower surface of the Transwell plates was coated with 10 μg of gelatin. HUVECs (1 × 105 cells) were loaded on the upper well. After a 4-h incubation, migrated cells were fixed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Non-migrating cells on the upper surface of the well were removed by wiping with a cotton swab, and migratory cells were observed by using an inverted phase-contrast microscope.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Quantification of protein band intensity obtained by Western blot was analyzed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and normalized to the density of the actin or Coomassie staining band. All data are presented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical comparisons between groups were done using Student's test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

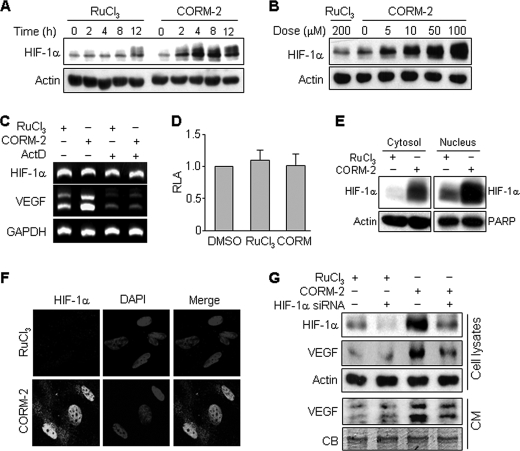

CO Induces VEGF Production by Increasing HIF-1α Protein Level

To evaluate whether human astrocytes exposed to CO affect angiogenesis of endothelial cells through a paracrine mechanism, in vitro angiogenesis assays were performed. CM from astrocytes treated with the CO-releasing molecule-2 (CORM-2) for 8 h significantly increased HUVEC proliferation, migration, and tube formation (supplemental Fig. S1). Because VEGF is one of the most potent angiogenic factors known (24), the potential role of VEGF in CO-induced angiogenesis was explored. CM-induced increases in endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation were significantly inhibited by treatment with a VEGF-neutralizing antibody but not by the addition of human IgG as a control (supplemental Fig. S1). These results suggest that paracrine-mediated angiogenic effects of CO-treated cells are derived from VEGF production. HIF-1α is necessary and sufficient for the hypoxia-induced expression of multiple angiogenic growth factors, including VEGF (13). We next examined the effect of CO on HIF-1α expression in human astrocytes. CORM-2 treatment significantly increased HIF-1α protein level in a time-dependent manner in comparison with the noncarbonyl inert control RuCl3, and maximal HIF-1α protein level was detected after 8 h of CORM-2 treatment (Fig. 1A). Exposure of astrocytes to concentrations of CORM-2 between 5 and 100 μm for 8 h resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in HIF-1α expression (Fig. 1B). We further examined whether ActD, a transcription inhibitor, had an effect on HIF-1α and VEGF mRNA levels. The HIF-1α mRNA level was not altered by treatment with CORM-2 alone or in combination with ActD. However, VEGF mRNA level was significantly increased in CORM-2-treated astrocytes, and this increase was blocked by co-treatment with ActD (Fig. 1C). We next examined whether CO regulates HIF-1α promoter activity. CORM-2 treatment did not affect HIF-1α promoter activity, compared with the solvent DMSO or negative control RuCl3 (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that CO promotes HIF-1α protein level without affecting transcriptional induction of HIF-1α and stimulates VEGF expression at the transcriptional step. HIF-1α is a well known transcription factor that easily translocates into the nucleus, where it regulates the transcription of various genes, including VEGF (22). Therefore, we examined the effect of CO on the translocation of HIF-1α into the nucleus. Western blot (Fig. 1E) and immunocytochemical analysis (Fig. 1F) showed that HIF-1α accumulated in the nuclear fraction and nuclei in CORM-2-treated cells, indicating that CO causes an increase in HIF-1α protein level in astrocytes, particularly in the nuclei. Furthermore, we examined the role of HIF-1α in VEGF expression in astrocytes treated with CORM-2. CORM-2 increases the protein levels of HIF-1α and VEGF, and these effects were blocked by specific knockdown of HIF-1α using siRNA (Fig. 1G). In addition, CORM-2 treatment enhanced the secretion of VEGF into culture medium, and this enhancement was reduced by transfection with HIF-1α siRNA (Fig. 1G). These results demonstrate that CORM-2 induces VEGF production by up-regulating HIF-1α protein level without affecting transcriptional induction of HIF-1α.

FIGURE 1.

CORM-2 up-regulates VEGF production via the augment of HIF-1α protein level. A and B, astrocytes were exposed to the indicated concentrations of RuCl3 and CORM-2 for various time periods (A) and for 8 h (B). HIF-1α and actin in cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. C, cells were pretreated with or without 1 μg/ml ActD for 30 min and exposed to RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) for 6 h. Cells were harvested, and total mRNAs were isolated. HIF-1α and VEGF mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-PCR. D, cells were transfected with pGL3-basic-pHIF-1α (0.4 μg) and pCMV-β-gal (0.4 μg) in 6-well plates. Transfected cells were incubated in fresh medium for 24 h and incubated with DMSO, RuCl3 (200 μm), and CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. Cell lysates were obtained, and relative luciferase activity (RLA) was determined using a luminometer. E, cells were treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. The cytosolic and nuclear fractions were isolated, and HIF-1α levels were detected by Western blotting. Actin and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) were used for internal controls. F, cells were treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min. Cells were immunostained with an antibody against HIF-1α (green) and DAPI (blue). Fluorescent images were obtained using a confocal microscope. G, astrocytes were transfected with control or HIF-1α siRNA (100 nm), cultured in fresh medium for 40 h, and then treated with 200 μm RuCl3 or 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. Cells were harvested, and cell lysates were prepared. The cellular levels of HIF-1α and VEGF were analyzed by Western blotting. For CM preparation, cells were transfected with control or HIF-1α siRNA (100 nm) and cultured in fresh medium for 16 h, followed by treatment with 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. The media were replaced with FBS-free M199 and cultured for 24 h. CM were collected and concentrated through a centrifugal filter device. VEGF protein level in CM was determined by Western blotting. CB, a Coomassie Blue-stained protein band as an internal control. Error bars, S.D.

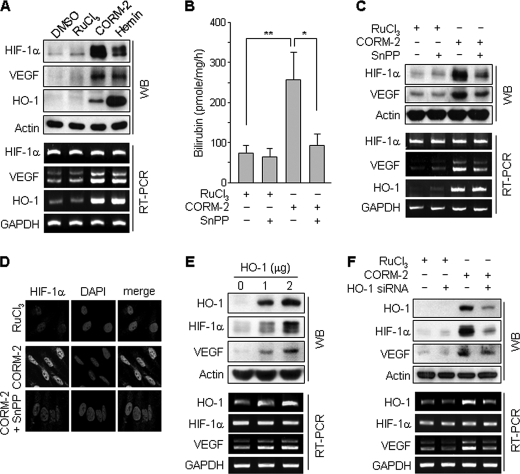

CO-induced Increases in HIF-1α and VEGF Expression Are Partially Mediated by HO-1 Induction

Because CO, produced by exogenous sources or catabolism of heme by HO-1, induces HO-1 expression in hepatoma cells (31), we examined a role of HO-1 in CORM-2-induced increases in HIF-1α protein and VEGF expression. Treatment of human astrocytes with CORM-2 or the HO inducer hemin resulted in an increase in the protein levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, and HO-1 (Fig. 2A). Treatment with CORM-2 or hemin increased mRNA levels of VEGF and HO-1 but not HIF-1α (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, HO enzyme activity was significantly increased in CORM-2-treated cell lysates, as determined by in vitro bilirubin production, and this increase was blocked by co-treatment with the HO inhibitor, SnPP (Fig. 2B). The CO-induced enhancement of VEGF mRNA and protein levels was blocked by co-treatment with SnPP (Fig. 2C). This inhibitor also inhibited CORM-2-induced increases in protein levels of HIF-1α (Fig. 2, C and D). These data suggest that up-regulation of HIF-1α protein level and VEGF induction by CORM-2 partially results from endogenous CO production via the induction of HO-1. We next examined the effect of endogenous CO on the regulation of HIF-1α and VEGF expression in astrocytes following transfection with an HO-1 expression vector and HO-1 siRNA. HO-1 overexpression increased the protein levels of HIF-1α and VEGF, as well as elevating the mRNA level of VEGF but not HIF-1α (Fig. 2E). In addition, CO-induced HIF-1α and VEGF protein levels were down-regulated by transfection with HO-1 siRNA (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that CO endogenously generated by HO-1 induction plays a role in the induction of HIF-1α and VEGF similar to CORM-2 and hemin treatment.

FIGURE 2.

CORM-2-induced HIF-1α and VEGF expressions are regulated by HO-1 activity. A, astrocytes were treated with DMSO, RuCl3 (200 μm), CORM-2 (100 μm), and hemin (10 μm) for 8 h. B, astrocytes were transfected with mock or HO-1 expression vector and cultured in fresh medium for 48 h. HO activity was assayed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data shown are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. C, astrocytes were treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h in the presence or absence of SnPP (50 μm). The protein and mRNA levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, and HO-1 were analyzed by Western blotting and RT-PCR. D, cells treated with RuCl3 (200 μm), CORM-2 (100 μm), or CORM-2 plus SnPP (50 μm) for 8 h were immunostained with an antibody against HIF-1α (green) and DAPI (blue). Fluorescent images were obtained by a confocal microscope. E, astrocytes were transfected with mock or HO-1 expression vector and cultured in fresh medium for 48 h. F, astrocytes were transfected with control or HO-1 siRNA (50 nm), cultured in fresh medium for 40 h, and then treated with 200 μm RuCl3 or 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. E and F, the protein and mRNA levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, and HO-1 were analyzed by Western blotting and RT-PCR. Error bars, S.D. WB, Western blot.

CO Increases HIF-1α Protein Level by Activating the Translational Pathway

Because Fig. 1 showed that CORM-2 treatment caused a significant increase in the protein level of HIF-1α without altering HIF-1α mRNA level, we examined whether CO affects HIF-1α translation or protein stability. Fig. 3A shows that CORM-2 induced a progressive accumulation of HIF-1α protein in astrocytes exposed to a nontoxic level of the 26 S proteasome inhibitor MG132 for up to 4 h compared with control cells, suggesting that CO enhances translation activity of HIF-1α. Indeed, treatment with the translation inhibitor CHx reduced the CORM-2-induced increase in HIF-1α protein level (Fig. 3B), suggesting that CO promotes HIF-1α translation. The PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK pathways have been shown to be involved in HIF-1α protein synthesis via functional activation of the translational regulatory proteins p70S6K and eIF-4E in various cells (13, 19, 32). We therefore examined whether CO stimulates HIF-1α synthesis through activation of these two pathways. CORM-2-induced increase in HIF-1α protein level was significantly reduced by co-treatment with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and the MEK inhibitor PD98059, whereas these inhibitors did not affect HIF-1α mRNA levels (Fig. 3C). Treatment of astrocytes with CORM-2 for 20 min effectively increased the phosphorylation of Akt and ERK, compared with control cells treated with RuCl3, which were inhibited by LY294002 and PD98059, respectively (Fig. 3D). Similar inhibitory effects of these inhibitors were also observed in cells treated with CORM-2 for 8 h (data not shown). CORM-2 treatment promoted the phosphorylation of both p70S6K (Thr-389 and Thr-421/Ser-424) and eIF-4E (Ser-206), and the phosphorylation of both proteins was effectively blocked by LY294002 and partially inhibited by PD98059 (Fig. 3E). Akt has been shown to activate mTOR, which plays an important role in protein synthesis (33). We next examined a role of mTOR in CO-induced phosphorylation of p70S6K and eIF-4E. Treatment with rapamycin, an mTOR kinase inhibitor, significantly reduced the CORM-2-induced protein level of HIF-1α and phosphorylation of p70S6K and eIF-4E (Fig. 3F), confirming that the Akt/mTOR pathway is involved in HIF-1α protein synthesis. We next examined the effect of CO on translation efficiency using sucrose gradient to isolate polysome fractions and RT-PCR to detect complex formation of HIF-1α mRNA with polysomes. In CORM-2-treated cells, high molecular weight polysomes were found deep in the sucrose gradient compared with RuCl3-treated control cells (Fig. 3G), indicating that CORM-2 enhanced protein synthesis. The polysome profile in fraction 17 showed that the increased translation in CORM-2-treated cells was inhibited when cells were pretreated with the MEK inhibitor (PD98059), PI3K inhibitor (LY294002), or mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) (Fig. 3H). HIF-1α mRNA levels in two high molecular weight polysome fractions (fractions 13–18 and fractions 19–24) in CORM-2-treated cells was increased, compared with control, and this increase was blocked by co-treatment with PD98059 (PD), LY294002 (LY), or RapM (Fig. 3I). These results suggest that the CO-induced up-regulation of HIF-1α protein level results from the activation of translational machinery through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways.

FIGURE 3.

CORM-2 regulates HIF-1α translation via the PI3K- and MEK-dependent pathways. A, astrocytes were treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) in the presence of MG132 (2.5 μm) for the indicated time periods, and cellular levels of HIF-1α and actin were determined by Western blotting. B, astrocytes were pretreated with or without 0.5 μg/ml CHx for 15 min and then incubated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. The cellular levels of HIF-1α were determined by Western blotting. C, cells were pretreated with 25 μm PD98059 (PD) or 10 μm LY294002 (LY) for 15 min and then treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. HIF-1α protein and mRNA levels were analyzed by Western blotting and RT-PCR, respectively. D, cells were treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or 100 μm CORM-2 in the presence or absence of 25 μm PD98059 or 10 μm LY294002 for 20 min. The cellular levels of phospho-Akt (p-Akt) and phospho-ERK (p-ERK) were determined by Western blotting. E and F, cells pretreated with 25 μm PD98059, 10 μm LY294002, or rapamycin (RapM; 100 and 200 nm) for 15 min and incubated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. The levels of phospho-p70s6k (p-p70s6k), phospho-eIF-4B (p-eIF-4B), p70s6k, eIF-4B, and HIF-1α were determined by Western blot analyses. G–I, cells pretreated with 25 μm PD98059, 10 μm LY294002, or 100 nm rapamycin for 15 min and incubated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or 100 μm CORM-2 for 8 h. G, 20–50% sucrose gradients were separated in 24 fractions (0.2 ml), which were collected and monitored for absorbance at a 254-nm wavelength. Each absorbance was calculated by subtracting the absorbance from blank-containing lysis buffer without cell extract. The average absorbance from three independent experiments is shown. H, the average absorbance of fraction 17 (arrowhead in G) was monitored from three independent experiments. #, p < 0.005 versus untreated control; *, p < 0.05 versus CORM-2 alone. I, RNA was extracted from fractions (a, fractions 13–18; b, fractions 19–24) indicated in G, and HIF-1α and GAPDH mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR. Shown are representative data from three independent experiments.

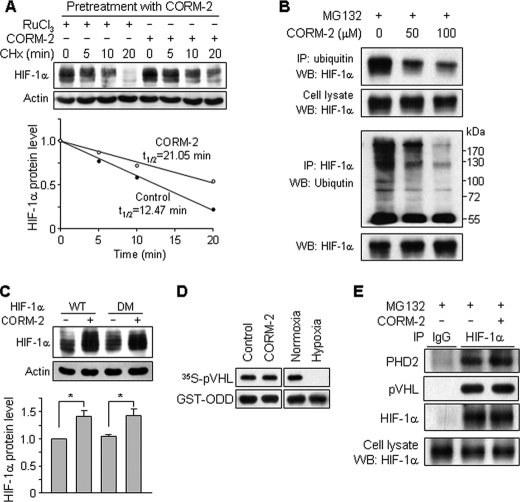

CO Increases HIF-1α Stability through the PHD-independent Pathway

We next determined whether CO regulates the stability of HIF-1α protein following treatment of astrocytes with CORM-2 for 8 h to induce HIF-1α expression and subsequent incubation with the translation inhibitor CHx with or without CORM-2. CHx treatment rapidly decreased pretreated CORM-2-induced HIF-1α protein level with a half-life of 12.5 min, and the increased protein level slowly disappeared with a half-life of 21.0 min by additional treatment with CORM-2 (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that the HIF-1α degradation pathway can be inhibited by CO. Because HIF-1α is degraded mainly through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway following PHD-dependent hydroxylation at proline residues 402 and 564 within ODD of HIF-1α (16–18), we next examined whether CO regulates ubiquitination of HIF-1α. Treatment of astrocytes with CORM-2 resulted in a decrease in HIF-1α ubiquitination, as determined by an immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 4B), suggesting that CO can prevent HIF-1α degradation by inhibiting ubiquitination of HIF-1α. We next examined whether CO regulates HIF-1α degradation through the hydroxylation at proline residues 402 and 564. Cells were transfected with wild-type HIF-1α or the double mutated HIF-1α vector (P402A/P564G), which introduces mutations at oxygen-dependent proline hydroxylation sites of HIF-1α, and HIF-1α protein levels were then measured following exposure of cells to CORM-2. Treatment of wild-type HIF-1α-transfected cells with CORM-2 caused an increase in protein levels of HIF-1α, which was not different from that of mutant HIF-1α-transfected cells (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the protein level of HIF-1α elevated by CO is not associated with hydroxylation at the proline residues within its ODD. We further examined whether CO regulates PHD activity by measuring interaction of 35S-labeled pVHL to GST-ODD (amino acids 401–603) as a substrate of hydroxylation. CORM-2 treatment did not affect the interaction between 35S-labeled pVHL and GST-ODD compared with control, whereas the interaction was completely blocked by low oxygen levels (hypoxia) compared with normoxia (Fig. 4D), indicating that CO does not regulate PHD activity. In addition, the interaction of HIF-1α with PHD2 and pVHL was not changed by CORM-2 compared with control (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that CO promotes HIF-1α stability by inhibiting HIF-1α ubiquitination through the PHD-independent pathway.

FIGURE 4.

CORM-2 increases HIF-1α protein stability. A, astrocytes were pretreated with CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h to increase HIF-1α protein level and further treated with RuCl3 (200 μm) or CORM-2 (100 μm) followed by CHx (0.5 μg/ml) treatment for the indicated time periods. The cellular levels of HIF-1α protein were determined by Western blot analysis. The relative protein levels of HIF-1α were calculated from the intensities of protein bands. B, astrocytes were treated with the indicated concentrations of CORM-2 combined with MG132 (10 μm) for 4 h, and cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using antibodies against ubiquitin and HIF-1α. Ubiquitinated HIF-1α was detected by immunoblotting (WB) these immunoprecipitates with antibodies against HIF-1α and ubiquitin. C, cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) HIF-1α or double-mutated (DM) (P402A/P564G) HIF-1α vector, cultured in fresh medium for 40 h, and then treated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. HIF-1α protein level was assessed by Western blotting (n = 6). *, p < 0.05. D, cells were treated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) for 4 h in the presence of MG132 (10 μm). Cell extracts were prepared and used for the PHD activity assay described under “Experimental Procedures.” Extracts prepared from cells cultured under normoxic and hypoxic conditions were used as controls. E, cells were treated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) in the presence of MG132 (10 μm) for 4 h. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an anti-HIF-1α antibody. Immunoprecipitates were separated by electrophoresis, and the protein levels of PHD2, pVHL, and HIF-1α were determined by Western blotting.

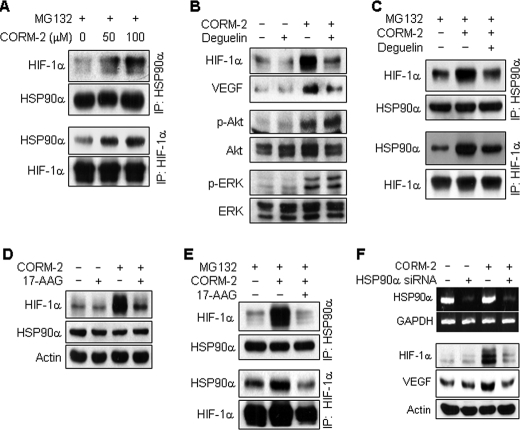

CO Increases HIF-1α Stability by Increasing Interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90α

Because HSP90α physically interacts with HIF-1α and inhibits HIF-1α ubiquitination, leading to the protection of HIF-1α from oxygen-independent degradation (12, 20, 21), we next investigated the effect of CORM-2 on the interaction between HSP90α and HIF-1α. Treatment of astrocytes with CORM-2 enhanced the interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90α in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Treatment of astrocytes with deguelin, a specific HSP90 inhibitor (21), caused a significant decrease in CO-induced increases in HIF-1α and VEGF protein levels, whereas this inhibitor did not affect Akt and ERK phosphorylation responsible for HIF-1α translation (Fig. 5B). The interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90α enhanced by CORM-2 was significantly reduced by co-treatment with deguelin (Fig. 5C). In addition, treatment with another HSP90 inhibitor, 17-AAG, reduced CORM-2-induced HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 5D) and decreased the CORM-2-enhanced interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90α (Fig. 5E). We further examined the effect of HSP90α-specific knockdown on the CO-induced increase in HIF-1α protein using an siRNA approach. When cells were transfected with HSP90α siRNA, CORM-2-induced increases in HIF-1α and VEGF protein levels were suppressed (Fig. 5F). These results suggest that CO can stabilize HIF-1α by promoting interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90α, which results in the inhibition of HIF-1α ubiquitination.

FIGURE 5.

CORM-2 increases HIF-1α protein stability by promoting its interaction with HSP90α. A, astrocytes were treated with or without CORM-2 in the presence of MG132 (10 μm) for 4 h, and cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using antibodies against HSP90α and HIF-1α. Immunoprecipitates were separated by electrophoresis, and protein levels of HIF-1α and HSP90 were determined by Western blotting. B, astrocytes were pretreated with 100 nm deguelin for 15 min and incubated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. The levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, phospho-Akt (p-Akt), and phospho-ERK (p-ERK) were determined by Western blot analyses. C, astrocytes pretreated with 100 nm deguelin for 15 min were incubated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) in the presence of MG132 (10 μm) for 4 h. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies against HSP90α and HIF-1α. Immunoprecipitates were separated by electrophoresis, and the levels of HIF-1α or HSP90 were determined by Western blotting. D, cells pretreated with or without 10 μm 17-AAG for 15 min were incubated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h, and the levels of HIF-1α or HSP90 were determined by Western blotting. E, cells pretreated with 10 μm 17-AAG for 15 min and incubated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) in the presence of MG132 (10 μm) for 4 h. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an antibody against HSP90α or HIF-1α. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against HIF-1α and HSP90. F, cells were transfected with control or HSP90 siRNA (75 nm), cultured in fresh medium for 40 h, and then treated with or without CORM-2 (100 μm) for 8 h. HSP90α and GAPDH mRNA levels were determined by RT-PCR, and protein levels of HIF-1α and VEGF were detected by Western blot analyses.

Inhibitors Regulating HIF-1α Protein Level Affect CO-mediated Angiogenic Activity

We next examined whether treatment of astrocytes with CO affects endothelial cell migration as an in vitro angiogenic indicator by VEGF expression via the regulation of translation and stability of HIF-1α protein. Astrocytes were pretreated with CORM-2 in the absence or presence of inhibitors of PI3K, MEK, HO, and HSP90 for 8 h, followed by replacement with fresh medium and co-culture with HUVECs in Transwell plates. Astrocytes treated with CORM-2 caused a significant increase in endothelial cell migration compared with control cells, and this effect was significantly reduced in astrocytes co-treated with LY294002, PD98059, SnPP, 17-AAG, or deguelin (Fig. 6A). Western blot analysis showed that CORM-2 caused a marked increase in VEGF secretion in astrocytes, which was significantly suppressed by co-treatment with those inhibitors (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that astrocytes exposed to CO elicit angiogenesis in a paracrine manner via HIF-1α-dependent VEGF expression and secretion by increasing both translation activity and protein stability of HIF-1α.

FIGURE 6.

CORM-2-treated astrocytes promote EC migration. A, astrocytes were pretreated with 25 μm PD98059 (PD), 10 μm LY294002 (LY), 50 μm SnPP (Sn), 10 μm 17-AAG (AA), or 100 nm deguelin (DG) in the lower chamber of Transwell plates for 15 min and treated with CORM-2 (COR; 100 μm) for 8 h. Cells were further cultured in fresh M199 containing 5% FBS for 20 h. HUVECs (1 × 105 cells) were seeded on the upper chamber of Transwell plates. After a 4-h incubation, endothelial cell migration was detected by counting migrated endothelial cells after staining with hematoxylin and eosin using an optical microscope. Upper panel, microscopic image; lower panel, statistical data with the mean ± S.D. (n = 4). #, p < 0.001 versus untreated control; **, p < 0.01 versus CORM-2 alone. B, astrocytes pretreated with indicated inhibitors for 15 min and treated with CORM-2 for 8 h. Cells were further incubated with FBS-free DMEM for 24 h. Culture media were used for analyzing the levels of VEGF by Western blotting. CB, a Coomassie Blue-stained protein band as an internal control. Top, a representative immunoblot; bottom, statistical data with the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). #, p < 0.001 versus untreated control; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus CORM-2 alone.

DISCUSSION

The present study was undertaken to elucidate the potential effect and molecular mechanism of CO on HIF-1α-dependent VEGF expression and angiogenesis. We found that astrocytes exposed to the CO donor CORM-2 elicited angiogenic activity by increasing VEGF production and secretion through the augmentation of HIF-1α protein level. These phenomena were correlated with stimulation of Akt- and ERK-dependent signaling pathways responsible for increasing translational activity of HIF-1α and elevation of HSP90 function associated with HIF-1α stability. The results demonstrate, for the first time, that CO increases HIF-1α-dependent VEGF expression in astrocytes by dual mechanisms: the de novo protein synthesis of HIF-1α through activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways responsible for activation of translational machinery and the stabilization of HIF-1α protein through the functional activation of HSP90, which inhibits proteasomal degradation of its interacting proteins, including HIF-1α.

CO is endogenously generated from heme by the catalytic reaction of HO-1 and HO-2. HO-1 is strongly induced in almost all cell types by cellular stressors, such as heat shock, heavy metals, UV, natural products, and oxidative stress (6). HO-2 is constitutively expressed and concentrated in the brain. Like the well known neuronal signal molecule nitric oxide (NO) synthesized by neuronal nitric-oxide synthase, CO produced by HO-2 acts as a neurotransmitter and vasodilator in the nervous system by activation of heme-containing soluble guanylyl cyclase to generate the second cellular messenger cGMP (34). HO-2 is selectively localized to neurons of the myenteric plexus in the gut and is highly co-localized with neuronal nitric-oxide synthase in these neurons (35, 36). NO and CO share similar functions in the neuronal system and blood vessels, such as neurotransmission, vasorelaxation, and angiogenesis. Like NO (37), CO can induce HO-1 expression and subsequent increase in CO production, which diffuses to adjacent endothelial cells and elicits phosphorylation-dependent activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase, resulting in increased production of NO in the vasculature (38). These observations indicate that there is cross-talk between endothelial nitric-oxide synthase/NO and HO-1/CO pathways in regulating the function of neurons and vasculature. This evidence demonstrates the notion that CO is a biologically active signaling molecule for vascular functions, such as vascular remodeling and angiogenesis (39).

Astrocytes perform many significant functions by acting as sensors of neuronal activity and providing a link between neurons and vessels (40). We found that human astrocytes constitutively express HO-2 (data not shown) and induce HO-1 expression following exposure to CORM-2. This indicates that CO can modulate HO-1 expression by a positive feedback mechanism (supplemental Fig. S2). Therefore, we hypothesized that neural and autocrine sources of CO can continuously stimulate astrocytes, which in turn stimulate the production of CO-induced angiogenic factors, including VEGF, the most potent angiogenic factor (24). In this study, we found that astrocytes exposed to CORM-2 promoted VEGF expression and that their angiogenic activity was completely blocked by a VEGF-neutralizing antibody, indicating that CO-mediated angiogenic activity is directly associated with production of VEGF. VEGF is a major target gene of the transcription factor HIF-1 and is considered a pivotal factor for vascular remodeling and angiogenesis (13, 22, 41). Our results showed that knockdown of HIF-1α by siRNA suppressed the enhancement of VEGF expression and secretion in astrocytes treated with CORM-2. This finding indicates that CO-induced angiogenesis is due to HIF-1α-dependent up-regulation of VEGF expression. Although the endogenous level of CO produced by HO-1 induction has not been reported in physiological and pathological conditions, the formation of blood vessels during wound healing is impaired in HO-1 knock-out mice (42), indicating that endogenously produced CO plays an important role in pathophysiological angiogenesis. Considering our finding that the gain-of-function and loss-of-function of HO-1 by transfection with the HO-1 gene and its siRNA oppositely regulate expression of HIF-1α and VEGF, endogenous concentration of CO generated by HO-1 would be sufficient to give the feed-forward effect on in vivo angiogenesis.

It has been demonstrated that the protein level of HIF-1α can be regulated by three different steps, such as transcription, translation, and protein stability (12). We tested whether CORM-2 up-regulates HIF-1α mRNA and HIF-1α promoter activity in human astrocytes cells because Chin et al. (43) showed that CO exposure to macrophage cells rapidly induced HIF-1α protein via up-regulation of its promoter activity. Our data revealed that CORM-2 increased VEGF mRNA and protein levels without changes in the steady-state level of HIF-1α mRNA and its promoter activity, indicating that CO did not affect transcription and stability of HIF-1α mRNA. This difference between our data and the result of Chin et al. (43) may be ascribed to the type or origin of cells used in these studies.

The rate of HIF-1α protein synthesis can be increased by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways (19, 44). These pathways phosphorylate and activate the translational regulatory proteins 4E-BP1 (eIF-4E-binding protein 1), p70S6K, and eIF-4E. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 disrupts its inhibitory interaction with eIF-4E, whereas activated p70S6K phosphorylates the 40 S ribosomal protein S6, leading to an increase in HIF-1α protein synthesis (13). Our data showed that CORM-2 increased phosphorylation-dependent activation of p70S6K and eIF-4E, which were suppressed by inhibitors of PI3K, mTOR, and MEK. In addition, these inhibitors also effectively blocked CORM-2-induced increase in HIF-1α mRNA translational efficiency assessed by a polysome assay. These results suggest that CO elevates HIF-1α protein synthesis via the activation of translational machinery.

A critical regulatory mechanism for HIF-1α stability is its rapid proteasomal degradation. In the presence of oxygen, proline hydroxylation of HIF-1α by PHD activity is a critical step for regulating its protein level. PHD belongs to an α-ketoglutarate (2-oxoglutarate)-dependent dioxygenase superfamily (45), which uses O2 as a co-substrate to add a hydroxyl group to specific proline residues within HIF-1α ODD (46). This enzyme requires ferrous iron (Fe2+) to assemble into its active conformation, and the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ loses the catalytic activity of PHD (47). Therefore, the oxidizing agents, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), inhibit PHD activity via the oxidation of iron, whereas reductants or antioxidants, such as ascorbate and cysteine, reduce the Fe3+ back to Fe2+ in order for the enzyme to be recycled (48, 49). Therefore, cellular redox potential can affect PHD activity and HIF-1α-dependent VEGF expression. Macrophages exposed to CO increase HIF-1α protein level through transient bursts of ROS arising from the mitochondria, and this increase is abrogated in the presence of catalase and superoxide dismutase (43, 50). This evidence suggests that the effect of CO on HIF-1α accumulation is attributable to the inhibition of PHD activity via generation of ROS from mitochondria. In this study, however, CORM-2-induced HIF-1α and VEGF protein expression in human astrocytes was not reduced by treatment with N-acetylcysteine, a ROS scavenger (data not shown). Our data showed that CORM-2 did not affect PHD activity and the interaction of HIF-1α with PHD2 or pVHL. These data indicate that CO increases HIF-1α protein level without altering PHD-dependent hydroxylation at proline residues within HIF-1α ODD. Recent studies demonstrated that HSP90α directly interacts with HIF-1α and protects it from oxygen- and PHD-independent ubiquitination and degradation (20, 21, 51, 52), resulting in the elevation of HIF-1α protein level and VEGF expression. In this study, CORM-2 increased HIF-1α stability by enhancing its interaction with HSP90α, consequently inhibiting HIF-1α ubiquitination. However, mechanisms by which CO regulates the interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90α should be further investigated.

VEGF secreted from astrocytes diffuses to adjacent or surrounding cells, including endothelial cells, and activates its cognate receptor(s), which is responsible for angiogenic processes (24, 53). We found that astrocytes exposed to CORM-2 accumulated significantly high levels of VEGF in conditioned medium, which increased the angiogenic process of endothelial cell migration. These events were significantly diminished by inhibitors of PI3K, MEK, and HSP90. We also found that CO-mediated increases in VEGF production were reduced by the transfection of HO-1 siRNA, indicating that CO-induced VEGF expression is in part mediated by HO-1 expression. It has also been demonstrated that VEGF stimulates HO-1 induction, which is required for VEGF-dependent angiogenesis because HO inhibitors abrogate the formation of blood (54). Therefore, our results suggest that there is a positive feedback circuit in the HO-1/CO/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling axis.

In conclusion, our present data demonstrate that CORM-2 increases HIF-1α protein level in astrocytes through the collaborative action of two mechanisms: activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways responsible for the translational activation of HIF-1α protein and functional activation of HSP90, which leads to an increase in protein stability and interaction of HIF-1α.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jozef Dulak (Jagiellonian University, Poland) for the gift of pcDNA/HO-1 vector, Dr. Gregg L. Semenza (The Johns Hopkins University) for the gifts of pcDNA3.1/HIF-1α vector and pcDNA3.1/HIF-1α DM vector, and Dr. Hyunsung Park (University of Seoul) for providing pcDNA3.1/hygro-VHL plasmid and pGEX-4T-1/HIF-1α-ODD plasmid. We thank Elaine Por for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Korea Science and Engineering Foundation Grant 2009-0062785 and a grant from the Korea Research Foundation (Regional Research Universities Program/Medical and Bio-Materials Research Center) funded by the Korean government.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- HO

- heme oxygenase

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ODD

- oxygen-dependent degradation domain

- pVHL

- von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein

- PHD

- proline hydroxylase

- CM

- conditioned media

- HSP90

- heat shock protein 90

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- ActD

- actinomycin D

- CHx

- cycloheximide

- SnPP

- Sn(IV) protoporphyrin IX dichloride

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- 17-AAG

- 17-demethoxygeldanamycin

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- DEPC

- diethylpyrocarbonate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otterbein L. E., Zuckerbraun B. S., Haga M., Liu F., Song R., Usheva A., Stachulak C., Bodyak N., Smith R. N., Csizmadia E., Tyagi S., Akamatsu Y., Flavell R. J., Billiar T. R., Tzeng E., Bach F. H., Choi A. M., Soares M. P. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauveau C., Bouchet D., Roussel J. C., Mathieu P., Braudeau C., Renaudin K., Tesson L., Soulillou J. P., Iyer S., Buelow R., Anegon I. (2002) Am. J. Transplant. 2, 581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foresti R., Bani-Hani M. G., Motterlini R. (2008) Intensive Care Med. 34, 649–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouard S., Otterbein L. E., Anrather J., Tobiasch E., Bach F. H., Choi A. M., Soares M. P. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1015–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenhunen R., Marver H. S., Schmid R. (1968) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 61, 748–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulak J., Deshane J., Jozkowicz A., Agarwal A. (2008) Circulation 117, 231–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cudmore M., Ahmad S., Al-Ani B., Fujisawa T., Coxall H., Chudasama K., Devey L. R., Wigmore S. J., Abbas A., Hewett P. W., Ahmed A. (2007) Circulation 115, 1789–1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deramaudt B. M., Braunstein S., Remy P., Abraham N. G. (1998) J. Cell. Biochem. 68, 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Józkowicz A., Huk I., Nigisch A., Weigel G., Dietrich W., Motterlini R., Dulak J. (2003) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 5, 155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabrese V., Stella A. M., Butterfield D. A., Scapagnini G. (2004) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 6, 895–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leffler C. W., Parfenova H., Fedinec A. L., Basuroy S., Tcheranova D. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H2897–H2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semenza G. L. (2007) Sci. STKE 2007, cm8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semenza G. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang G. L., Jiang B. H., Rue E. A., Semenza G. L. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5510–5514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein A. C., Gleadle J. M., McNeill L. A., Hewitson K. S., O'Rourke J., Mole D. R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M. I., Dhanda A., Tian Y. M., Masson N., Hamilton D. L., Jaakkola P., Barstead R., Hodgkin J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001) Cell 107, 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaakkola P., Mole D. R., Tian Y. M., Wilson M. I., Gielbert J., Gaskell S. J., Kriegsheim Av., Hebestreit H. F., Mukherji M., Schofield C. J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001) Science 292, 468–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salceda S., Caro J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 22642–22647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivan M., Kondo K., Yang H., Kim W., Valiando J., Ohh M., Salic A., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2001) Science 292, 464–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda R., Hirota K., Fan F., Jung Y. D., Ellis L. M., Semenza G. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38205–38211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong X., Lin Z., Liang D., Fath D., Sang N., Caro J. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2019–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh S. H., Woo J. K., Yazici Y. D., Myers J. N., Kim W. Y., Jin Q., Hong S. S., Park H. J., Suh Y. G., Kim K. W., Hong W. K., Lee H. Y. (2007) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99, 949–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxwell P. H., Dachs G. U., Gleadle J. M., Nicholls L. G., Harris A. L., Stratford I. J., Hankinson O., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 8104–8109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ema M., Taya S., Yokotani N., Sogawa K., Matsuda Y., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4273–4278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millauer B., Wizigmann-Voos S., Schnürch H., Martinez R., Møller N. P., Risau W., Ullrich A. (1993) Cell 72, 835–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraisl P., Mazzone M., Schmidt T., Carmeliet P. (2009) Dev. Cell 16, 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffe E. A., Nachman R. L., Becker C. G., Minick C. R. (1973) J. Clin. Invest. 52, 2745–2756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balla G., Jacob H. S., Balla J., Rosenberg M., Nath K., Apple F., Eaton J. W., Vercellotti G. M. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 18148–18153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon E. J., Jeong C. H., Jeong J. W., Kim K. R., Yu D. Y., Murakami S., Kim C. W., Kim K. W. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 382–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee M. S., Moon E. J., Lee S. W., Kim M. S., Kim K. W., Kim Y. J. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 3290–3293 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koritzinsky M., Wouters B. G. (2007) Methods Enzymol. 435, 247–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee B. S., Heo J., Kim Y. M., Shim S. M., Pae H. O., Kim Y. M., Chung H. T. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 343, 965–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson R. T., Desai B. N., Hardwick J. S., Schreiber S. L. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4438–4442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunavala-Dossabhoy G., Fowler M., De Benedetti A. (2004) BMC Mol. Biol. 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verma A., Hirsch D. J., Glatt C. E., Ronnett G. V., Snyder S. H. (1993) Science 259, 381–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Battish R., Cao G. Y., Lynn R. B., Chakder S., Rattan S. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 278, G148–G155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zakhary R., Poss K. D., Jaffrey S. R., Ferris C. D., Tonegawa S., Snyder S. H. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 14848–14853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pae H. O., Oh G. S., Choi B. M., Kim Y. M., Chung H. T. (2005) Endocrinology 146, 2229–2238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwer C. I., Mutschler M., Stoll P., Goebel U., Humar M., Hoetzel A., Schmidt R. (2010) Mol. Pharmacol. 77, 660–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryter S. W., Morse D., Choi A. M. (2004) Sci. STKE 2004, RE6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbott N. J., Rönnbäck L., Hansson E. (2006) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikeda E., Achen M. G., Breier G., Risau W. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19761–19766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deshane J., Chen S., Caballero S., Grochot-Przeczek A., Was H., Li Calzi S., Lach R., Hock T. D., Chen B., Hill-Kapturczak N., Siegal G. P., Dulak J., Jozkowicz A., Grant M. B., Agarwal A. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 605–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chin B. Y., Jiang G., Wegiel B., Wang H. J., Macdonald T., Zhang X. C., Gallo D., Cszimadia E., Bach F. H., Lee P. J., Otterbein L. E. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5109–5114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laughner E., Taghavi P., Chiles K., Mahon P. C., Semenza G. L. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3995–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruick R. K., McKnight S. L. (2001) Science 294, 1337–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirsilä M., Koivunen P., Günzler V., Kivirikko K. I., Myllyharju J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30772–30780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan Y., Mansfield K. D., Bertozzi C. C., Rudenko V., Chan D. A., Giaccia A. J., Simon M. C. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 912–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Counts D. F., Cardinale G. J., Udenfriend S. (1978) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 2145–2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerald D., Berra E., Frapart Y. M., Chan D. A., Giaccia A. J., Mansuy D., Pouysségur J., Yaniv M., Mechta-Grigoriou F. (2004) Cell 118, 781–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veal E. A., Day A. M., Morgan B. A. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isaacs J. S., Jung Y. J., Mimnaugh E. G., Martinez A., Cuttitta F., Neckers L. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29936–29944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Y. V., Baek J. H., Zhang H., Diez R., Cole R. N., Semenza G. L. (2007) Mol. Cell 25, 207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee S. W., Kim W. J., Choi Y. K., Song H. S., Son M. J., Gelman I. H., Kim Y. J., Kim K. W. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 900–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bussolati B., Ahmed A., Pemberton H., Landis R. C., Di Carlo F., Haskard D. O., Mason J. C. (2004) Blood 103, 761–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.