Abstract

A forward genetic screen of mice treated with the mutagen ENU identified a mutant mouse with chronic motor incoordination. This mutant, named Pingu (Pgu), carries a missense mutation, an I402T substitution in the S6 segment of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kcna2. The gene Kcna2 encodes the voltage-gated potassium channel α-subunit Kv1.2, which is abundantly expressed in the large axon terminals of basket cells that make powerful axo-somatic synapses onto Purkinje cells. Patch clamp recordings from cerebellar slices revealed an increased frequency and amplitude of spontaneous GABAergic inhibitory postsynaptic currents and reduced action potential firing frequency in Purkinje cells, suggesting that an increase in GABA release from basket cells is involved in the motor incoordination in Pgu mice. In line with immunochemical analyses showing a significant reduction in the expression of Kv1 channels in the basket cell terminals of Pgu mice, expression of homomeric and heteromeric channels containing the Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit in cultured CHO cells revealed subtle changes in biophysical properties but a dramatic decrease in the amount of functional Kv1 channels. Pharmacological treatment with acetazolamide or transgenic complementation with wild-type Kcna2 cDNA partially rescued the motor incoordination in Pgu mice. These results suggest that independent of known mutations in Kcna1 encoding Kv1.1, Kcna2 mutations may be important molecular correlates underlying human cerebellar ataxic disease.

Keywords: Mouse Genetics, Mutant, Neurological Diseases, Neuron, Potassium Channels, CHO Cells, Inhibitory Post-synaptic Currents, Voltage-gated Potassium Channel Kv1.2, Missense Mutation

Introduction

Voltage-gated potassium channels play a key role in neuronal excitability and plasticity and are critical in establishing resting membrane potential and firing thresholds, repolarizing action potentials, and limiting excitability (1). Channels are unevenly distributed throughout the brain as a whole and also within individual neurons (2–10). Therefore, the particular utility of any given channel depends not only on its specific channel properties and stoichiometry but also on its particular localization and density within a cell or cellular compartment. In the cerebellum, the genes Kcna1 and Kcna2 encode the voltage-gated potassium channel subunits Kv1.1 and Kv1.2, respectively, which contribute to the low voltage-activated potassium current IKv1 and are coexpressed in the presynaptic GABAergic pinceaus of spontaneously firing basket cell interneurons that provide a strong inhibitory input to Purkinje cells (5–9). The shunting effect of this inhibitory conductance has been shown through modeling to have a steep correlation with the prolongation of Purkinje cell interspike intervals in vitro (11–13).

The cerebellum is involved in the regulation of the initiation and timing of movements and is important for maintaining balance and posture (14). At the core of the cerebellar computational circuitry, the spontaneously spiking Purkinje cells integrate cerebral cortical and sensory, excitatory and inhibitory inputs encoding relevant information in their action potential discharge and communicate the information to the deep cerebellar nuclei for the final output of the cerebellum (15). The total synaptic conductance invading a Purkinje cell effectively functions to clamp the subthreshold membrane voltage, thereby controlling the state of the active conductances that determine each Purkinje cell intrinsic pacemaking activity, which in turn shapes the tonic GABAergic inhibition targeted to the deep cerebellar nuclei (11).

Missense mutations of Kcna1 are associated with type 1 episodic ataxia (EA1)3 (16), whereas mice carrying the EA1-associated V408A mutation show stress-induced loss of motor coordination and a greater frequency and amplitude of spontaneous GABAergic IPSCs in cerebellar Purkinje cells (17). However, the effects of mutations in Kcna2 are unknown despite the fact that Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 are commonly present within the same tetramers (18, 19). To this end, we characterized the in vivo and in vitro effects of a missense mutation (I402T; Pgu allele) in the S6 segment of the Kv1.2 α-subunit in mice. Here, we report that mice carrying the Pgu mutant allele of Kcna2 exhibit dominantly inherited chronic motor incoordination, due at least in part to an enhanced GABAergic inhibitory tone from basket cells onto Purkinje cells in the cerebellum.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice and ENU Mutagenesis

Male C57BL/6J (B6) mice (The Jackson Laboratory) received three intraperitoneal injections of ENU (85 mg/kg) as previously described (20). Ten weeks after the last ENU injection, the mutagenized males were bred to untreated C3H/HeJ (C3H) female mice (The Jackson Laboratory). G1 progeny (C3HB6F1) of this cross were screened at postnatal day 28 for abnormalities in behavior or appearance using a modified SHIRPA protocol (Centre for Modeling Human Disease, Toronto Centre for Phenogenomics). A male mouse exhibiting an abnormal gait with splayed hind limbs was discovered and named Pingu (Pgu). This founder male was bred to C3H females, and the resulting G2 progeny were put through the same behavior and appearance screen as their sire. Mice exhibiting the characteristic abnormal gait of the Pgu founder were classified as “affected” and further backcrossed to C3H for four generations (G3-G6) to reduce the B6 proportion of the genetic background and facilitate genetic mapping of the mutation. To investigate the homozygous phenotype of the Pgu mutation, affected G4 mice were intercrossed. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Genetic Mapping

To localize the Pgu mutation to a specific chromosomal region, a panel of 85 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between the B6 and C3H parental strains were used to scan the entire genomes of 16 affected and 8 unaffected G2 Pgu mice at a resolution of ∼25 centimorgans. After the Pgu mutation had been mapped to a 57.4-Mb interval of chromosome 3 between SNP markers rs3680671 (84.1 Mb) and rs3699582 (141.5 Mb), additional SNPs were used to refine the critical interval to 3.3 Mb in a total of 260 G3-G6 mice. Genomic DNA was extracted from tail tissue using a standard procedure. The fluorescence polarization SNP genotyping assay was used for genotyping. PCR protocols and the SNP single base extension reaction conditions have been described previously (20).

Pgu Mutation Screen

The gene structure of mouse Kcna2 was obtained from a public data base (UCSC Genome Bioinformatics). Four pairs of PCR primers, F1 (5′-GCTTTCCTGCAGAAGCTCAG-3′) and R1 (5′-TCATCCTCCCGAAACATCTC-3′), F2 (5′-ACCTGTGAACGTGCCCTTAG-3′) and R2 (5′-CTCTGTCCCCAGGGTGATAA-3′), F3 (5′-AAAGCTGGCTTCTTCACCAA-3′) and R3 (5′-TGCTCCTCTCCCTCTGTCTC-3′), and F4 (5′-GGGGGAAGATAGTGGGTTCT-3′) and R4 (5′-CATGCAGAACCAGATGCTGT-3′), were designed from genomic DNA to amplify the coding region of mouse Kcna2 (GenBankTM accession number NM_008417). PCR products were sequenced using an automated sequencer (ABI Prism 377; Applied Biosystems). Because the Kcna2 Pgu mutation generated a BtsI restriction site, primer pair F3 and R3 and enzyme BtsI (New England Biolabs) were used for Pgu genotyping.

Transgenic Complementation of the Pgu Mutation

The Kcna2 cDNA coding region was amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of a wild-type mouse using primers F (5′-CCTGAAGCTTGCCGCCACCATGACAGTGGCTACCGGAGACC-3′) and R (5′-CATGAAGCTTTCACTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTAGACATCAGTTAACATTTTGGTAATATTC-3′). Both primers contain a HindIII site for subcloning purposes. The FLAG epitope (YYKDDDDK) was incorporated immediately upstream of the stop codon for detection of the transgene protein. The 1.5-kb PCR products of the wild-type Kcna2 coding sequence were TA-cloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen) and sequenced, then subsequently inserted into the HindIII site of the pNSE-Ex4 vector (21) (gift from Dr. Michael B. A. Oldstone, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). To prepare DNA for oocyte microinjection, the vectors were digested with SalI, and the fragments of roughly 6.5 kb were isolated and purified from an agarose gel. Transgenic mice were produced on the FVB.129P2 background at the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Institute Transgenic Core. Specific PCR primers, pNSE-F1 (5′-CTACCCACTGCAGTAACCTC-3′ (within intron 1 of the rat Eno2 gene)) and pNSE-R (5′-CTTGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGT-3′ (containing FLAG-tag sequences)) were designed for the transgenic construct so that endogenous Kcna2 DNA was not amplified. Genotyping of transgenic mice was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from mice tail snips followed by digestion of the PCR product with BtsI. The founder transgenic mouse was crossed to Pgu mutant mice with a G6 FVB.129P2 background. Total RNA was extracted from the cerebellum of transgenic mice and used to synthesize cDNA first strand using the SuperScriptTM First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). The additional specific RT-PCR primer pNSE-F2 5′-TCGCAAGCTTGCCGCCACCA-3′ (containing HindIII and Kozak sequences) was designed for the transgenic construct so that endogenous Kcna2 cDNA first strand would not be amplified.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice at the age of 6–8 weeks were deeply anesthetized with avertin and transcardially perfused with 50 ml of chilled fixative containing 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer. The brains were removed and post-fixed in the same fixative buffer overnight at 4 °C. The fixed brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline overnight at 4 °C. The frozen sagittal sections were cut at 20 μm and permeabilized in the blocking buffer containing 10% normal goat serum, 0.4% Triton X-100, and 0.02% sodium azide in 0.1 m phosphate buffer for 1–2 h at room temperature. The primary antibody used was rabbit anti-Kv1.2 polyclonal antibody (Chemicon) at 1:100 dilutions.

Western Blotting

20 μg of protein extracted from the cerebellum of 6–8 week-old mice was subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with polyclonal antibodies rabbit anti-Kv1.2 (Chemicon), rabbit anti-Kv1.1 (Abcam), and rabbit anti-β-tubulin III polyclonal antibody (Sigma) in accordance with the vendor's instructions. Densitometry analysis of scanned film (measured as arbitrary units) using ImageJ Version 1.37 software (rsb.info.nih.gov) was undertaken to quantify the visualized bands. Mutant and wild-type immunoreactivity levels, expressed as (Kv1.2 or Kv1.1 signal/β-tubulin III signal) × 100, were compared using Student's two-sample t test. For the transgenic mouse study, 10 μg of protein extracted from the cerebellum of 6–8-week-old mice was used.

Motor Behavioral Tests

Mice at the age of 8–12 weeks were placed on an accelerating rotarod (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) and were observed at an initial speed of 4 rpm for 30 s. The rod was then gradually accelerated at a rate of 0.2 rpm/second. The latency to fall was recorded with a cutoff time of 3 min. Mice were given three trials each day with 30 min rests between trials for 3 consecutive days. The latency to fall for each mouse was counted by averaging over the three trials in each day. The beam-walking test was performed on a round beam (1.8-cm diameter × 90 cm long) suspended 50 cm above bedding. Mice were trained to traverse the length of the beam in four successive trials the day before testing. On the day of the test, mice were given one trial across the beam. The time for a mouse walking across the beam and the number of hind feet missteps were recorded. Footprint analyses were performed by placing the mice hind feet into ink and recording walking patterns, whereas the mice walked continuously across the runway. Footprints software Version 1.2 (22) was used to measure stride length, stride width, and the distance between toes 1–5, toes 2–4, and toe 3 to heel (foot length). The grip strength of four limbs and forelimbs was determined in adult females using a grip strength meter (San Diego Instruments). A mouse was held by the tail and lowered over the mesh grid until it could easily grip the grid with four limbs or forelimbs. The tail was then steadily and horizontally pulled away from the mesh grid until the mouse released its grip. The maximal force in grams required to relieve this grip was recorded manually. Each mouse was subjected to three trials with 5-min rests between trials. The average score (grams) of the three trials for each mouse was reported.

Drug Administration

Acetazolamide (Sigma) was administered by intraperitoneal injection at a volume of 0.01 ml/g. Acetazolamide was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl (1 m NH4OH) to produce a 50 mg/ml stock solution and was injected at a dosage of 30 mg/kg 30 min before motor behavioral tests. In the accelerating rotarod test, mice were given three training trials for three consecutive days and tested on the fourth day for three trials. In the beam-walking test, mice were trained as described previously and were given one test trial after administration of the drug.

Cloning and Expression in CHO Cells

Mouse wild-type or I402T mutation Kcna2 cDNA coding sequence was subcloned into pEGFP-C3 as an XhoI/HindIII fragment. Mouse wild-type Kcna1 cDNA coding sequence was subcloned into pDsRed2-C1 as an XhoI/HindIII fragment. The clones were sequenced to confirm the presence of the wild-type or I402T mutant cDNA coding sequence. CHO cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic at 37 °C. Cells were split and seeded on poly-d-lysine (50 μg/ml)-coated glass coverslips in 6-well plates 1 day before transfection in a manner such that the confluence reaches 50% at the time of transfection. In each well, 0.5 μg of each DNA plasmid, respectively, was transfected using Attractene reagent (Qiagen). Medium was changed 3–4 h later. Recordings were performed 48–72 h post-transfection.

Electrophysiology

Slicing and Slice Solutions

Parasagittal slices of 3.5–6-week-old mouse cerebella were cut at a thickness of 250–300 μm using a vibrating microtome (Leica VT 1000S, Wetzlar, Germany) in ice-cold solution containing 81.2 mm NaCl, 23.4 mm NaHCO3, 69.9 mm sucrose, 23.3 mm glucose, 2.4 mm KCl, 1.4 mm Na2HPO4, 6.7 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm CaCl2 at a pH of 7.3 when bubbled in 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The slices were incubated in the same solution at 34 °C for 30 min after which time the slices were incubated for an additional 30 min at 34 °C in a solution containing 125 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 10 mm glucose, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 2 mm sodium pyruvate, 3 mm myo-inositol, 0.5 mm ascorbic acid, 26 mm NaHCO3, 1 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm CaCl2 at a pH of 7.3 when bubbled in 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and then stored at room temperature. During action potential recordings slices were superfused with the above solution, and to facilitate IPSC recording 10 μm NBQX was included. For synaptic experiments in Purkinje cells, the pipette solution contained 50 mm potassium gluconate, 80 mm CsCl, 5 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm MgCl2, and 3 mm lidocaine N-ethyl bromide (QX314) (an intracellular blocker of Na+ currents), pH 7.3. For cell-attached recordings, the above pipette solution was used but without the inclusion of QX314. Reagents were purchased from Sigma, Tocris, and Alomone Labs.

Slice Recording and Perfusion Techniques

Parasagittal slices were transferred to a continuously perfused recording chamber, with a flow-rate set at approximately (1 ml/min), mounted on an Olympus microscope with Nomarski optics and a 60× water immersion objective. Purkinje cell bodies were identified by their large size, layered arrangement, and large dendritic tree. In the voltage-clamp mode spontaneous Purkinje cell IPSCs were recorded at −60 mV, as were mIPSCs in the presence of tetrodotoxin (1 μm). In the cell-attached mode, action potentials at the soma generated action currents that were detected with the holding potential at the pipette set at 0 mV. Basket cells were identified by their size and location in the innermost one-third of the molecular layer within a distance of ∼40 μm from the Purkinje cell body layer. The few recordings that did not give action potentials were discarded and were assumed to be from Bergmann glial cells.

CHO Cell Recording

Glass coverslips were removed from the 6-well plates and placed in a recording chamber filled with recording solution, mounted on an Olympus microscope with Normarski optics and a 60× water immersion objective. Visually healthy cells, which were isolated and not in contact with other cells, were selected for whole cell recording. Fluorescence microscopy was used to determine the expression of either enhanced green fluorescent protein and/or DsRed. The recording solution contained 145 mm NaCl, 2.8 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm d-glucose, and 10 mm HEPES at a pH of 7.3. For whole cell current recordings in CHO cells, the pipette solution contained 97.5 mm N-methyl-d-glucamine, 32.5 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 5 mm EGTA, and 1 mm MgCl2 at a pH of 7.3. N-Methyl-d-glucamine was used as a non-permeable cationic ion to minimize clamp errors by reducing current amplitude.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Data were acquired online using PATCHMASTER software and an EPC10 patch clamp amplifier (Heka Electronics Inc.), filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10–50 kHz, and analyzed off-line with pClamp9 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and Mini Analysis software (Synaptosoft, Inc., Decater, GA). Results were compiled, and statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and GraphPad (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). All experiments were performed at room temperature. Values are given as the means ± S.E., and confidence limits were determined using Student's t tests.

RESULTS

Derivation of the I402T Kv1.2 Mutation

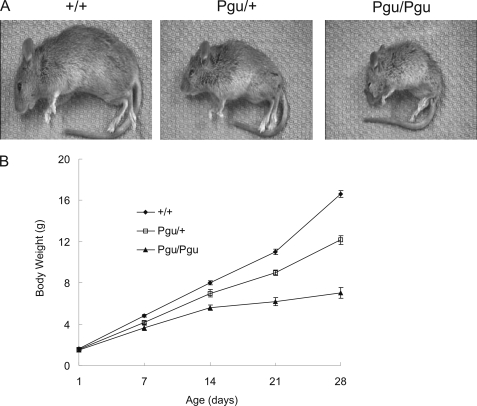

The founder Pgu mutant was identified on the basis of its abnormal gait in a behavior and appearance screen of 3733 C3HB6F1 hybrid progeny of ENU-mutagenized B6 males and untreated C3H females. Heterozygous Pgu/+ mice were recognizable at postnatal day 21 (P21) by their smaller body (Fig. 1A) and an abnormal gait with a higher stance and splayed hind limbs. Of 152 intercross progeny of G4 Pgu/+ mutants, 74 (48.7%) mice were smaller than their healthy littermates at P21 and exhibited an abnormal gait similar to that of their Pgu/+ parents; 37 (24.3%) mice had a recognizably smaller body size at P7 compared with their wild-type littermates (+/+) and exhibited a hind limb grasping reflex in response to tail suspension and a more severe gait abnormality at P10, whereas 41 (27%) mice appeared phenotypically normal. These phenotypic proportions demonstrate that the abnormal phenotype in Pgu mutants was inherited as an autosomal semi-dominant trait. Heterozygous Pgu/+ mice had a normal life-span like their +/+ littermates. Approximately 50% of homozygous Pgu/Pgu mice (B6C3H hybrid background) died between their third and sixth weeks of life (P15 to P35). Homozygotes surviving beyond 6 weeks of age have been maintained for more than 12 months. The motor incoordination of Pgu mice did not progressively worsen with age. The body weight of Pgu mice and their +/+ littermates was not significantly different on the day of birth (P1), but the growth of Pgu mutants was significantly delayed from P7 to P28 (Fig. 1B). No abnormalities of neuronal migration were noted in the cortex of Pgu mice.

FIGURE 1.

Pgu mice showed severe postnatal growth retardation. A, shown are the body sizes of a heterozygous Pgu/+, a homozygous Pgu/Pgu mouse, and their +/+ littermate at postnatal day 21. B, shown is a comparison of the body weight between Pgu/+, Pgu/Pgu mice, and +/+ controls from P1 to P28 (supplemental Table 1).

The Pgu mutation was mapped to a 3.3-Mb nonrecombinant interval of chromosome 3 between SNP markers rs13477313 (106.6 Mb) and rs3712218 (109.9 Mb) (Fig. 2A). Sequencing of the candidate genes within this interval, including a cluster of potassium channel genes, identified a T-to-C transition at nucleotide 1886 of Kcna2 in Pgu mutants that causes an isoleucine to threonine substitution at residue 402 in the S6 transmembrane domain of Kv1.2 (Fig. 2B). Given the conservation of I402 within the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1 subfamily (Fig. 2C), we postulated that the I402T mutation causes a similar phenotype to Kv1.1 missense mutations, which have been associated with human ataxia.

FIGURE 2.

Positional cloning of the Pgu mutation. A, high resolution haplotype mapping of Pgu mutation on mouse chromosome 3 (Chr. 3) is shown. White squares indicate C3H homozygotes; gray squares indicate B6/C3H heterozygotes. The SNPs defining the minimal interval are shown in bold text. Map positions are in accordance with the public mouse genome assembly (Ensembl). B, shown is sequencing of mouse candidate Kcna2 cDNA revealed a T-to-C transition at nucleotide residue 1886, leading an isoleucine to threonine substitution at residue 402 in Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice. C, shown is a protein sequence alignment of the S6 transmembrane domain (bold text) of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1 subfamily in human and mouse genome. The Pgu I402T mutation is indicated by an arrow.

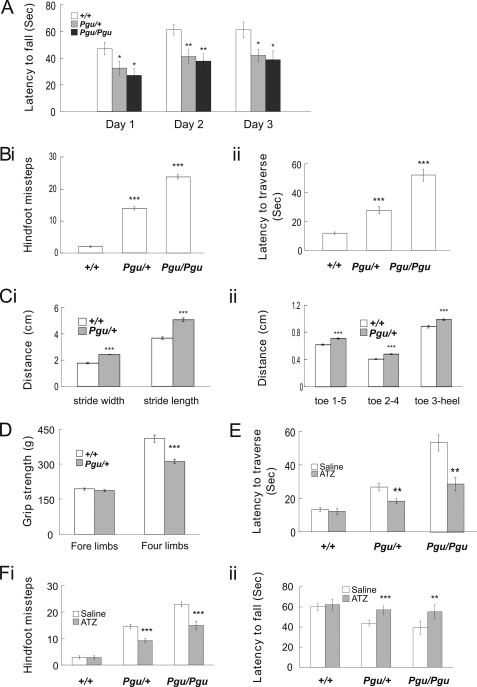

Motor Coordination Deficits in Pgu Mice

In the accelerating rotarod test, Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice had difficulty remaining on the rotating rod and had markedly shorter latency to fall than +/+ mice (Fig. 3A). The rotarod deficit was not significantly different between Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice. In the balance beam-walking test, both Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice performed poorly and exhibited flattened posture, severe tremors, myoclonic jerks, and ataxic movement when walking across the beam. Pgu/Pgu mice had more difficulty than Pgu/+ mice in performing this task. The numbers of hind-foot slips (Fig. 3Bi) and the latency to traverse the beam (Fig. 3Bii) were both significantly increased in Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice compared with +/+ mice. Footprint analysis revealed that Pgu/+ mice had a significantly increased stride length and stride width of the hind limbs compared with +/+ mice (Fig. 3Ci). Interestingly, Pgu/+ mice also showed a significantly increased toe spread between toes 1 and 5, toes 2 and 4, and toe 3 and the heel compared with +/+ mice (Fig 3Cii). Despite Pgu/+ mice having a smaller body size than +/+ littermates, direct measurement of the distances between toes 1 and 5, toes 2 and 4, and toe 3, and the heel in live mice showed no significant differences between the two groups (data not shown). This suggests that Pgu/+ mice spread their toes further apart to maintain stability and balance. In a grip strength test, Pgu/+ mice exhibited significantly reduced grip strength when using all four limbs (311.9 ± 9.4 g, n = 13) compared with +/+ mice (409.3 ± 15.1 g, n = 11; p = 1.21 × 10−5). However, the grip strength of the forelimbs alone showed no significant difference between Pgu/+ (186.1 ± 3.66 g) and +/+ mice (193.2 ± 14.1 g; p = 0.603) (Fig. 3D). The disparity between these two measures would suggest significantly lower grip strength in the hind limbs of Pgu/+ mice. Pgu/Pgu mice, as expected, showed significantly poorer gait performance and lower grip strength than Pgu/+ and +/+ mice (data not shown). However, because of the significantly smaller body size as well as the large variations in body size, exhibited in Pgu/Pgu mice, meaningful statistical comparison was difficult, and therefore, the data were not included.

FIGURE 3.

Motor coordination deficits in Pgu mice. A, latency to fall off the accelerating rotarod is shown. Results were averaged over three trials each day for three consecutive days (supplemental Table 2). Hind-foot missteps on the balance beam (Bi) and latency to traverse the beam (Bii) are shown (supplemental Table 2). Hind-limb footprint analysis of stride width (Ci) and stride length and toe spread (Cii) are shown (supplemental Table 3). D, grip strength of the fore limbs and all four limbs is shown. E, intraperitoneal injection of ATZ significantly increased the latency to fall in Pgu mutant mice compared with the injection of saline (supplemental Table 4). F, i and ii, balance beam performance improved in Pgu mice after injection of ATZ compared with injection of saline is shown (supplemental Table 4). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Acetazolamide (ATZ), a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, is used empirically to reduce the severity and frequency of attacks of ataxia in episodic ataxia patients (23, 24) and has been shown to ameliorate the stress-induced loss of motor coordination in a mouse model of EA1 (17). Injection of ATZ before the motor coordination tests abolished the reduction in latency of Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice to fall from the accelerating rotarod (Fig. 3Fi). Similarly, ATZ significantly reduced the number of hind-foot slips and the latency to traverse the beam of Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice (Fig. 3Fii). This behavioral data suggests that Kcna2 Pgu mutants share common pathological traits with typical cerebellar ataxia, which can be partially rescued by ATZ.

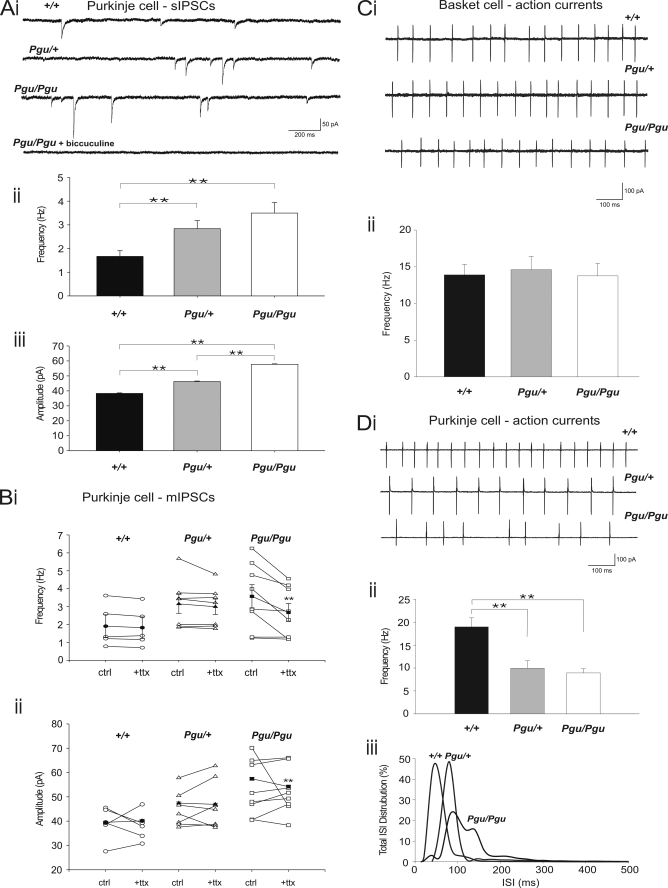

Increased Spontaneous GABAergic IPSCs and Larger Miniature IPSCs in Pgu Mice

The primary localization of Kv1.2 in the GABAergic pinceaus of basket cells in the cerebellum (6–10) suggests that the motor behavioral impairments in Kcna2 Pgu (Kv1.2 I402T) mutants could be affected at least in part by a change in GABAergic transmission from basket cells to Purkinje cells. Whole cell voltage-clamp recordings from Purkinje cells in acute cerebellar slice were used to monitor the cellular effects of the Kv1.2 I402T substitution on the spontaneous inhibitory GABAergic tone seen by Purkinje cells. At a holding potential of −60 mV, in the presence of the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX (10 μm), spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs) were routinely observed (Fig. 4Ai). Inclusion of the γ-aminobutyric acid, type A blocker bicuculline (10 μm) blocked all events, confirming their identity as inhibitory GABAergic postsynaptic currents. These recordings revealed that both the frequency (Fig. 4Aii) and the amplitude (Fig. 4Aiii) of sIPCS were significantly higher in Pgu mutants compared with +/+ mice. Between Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice, the amplitude of sIPSCs was significantly higher (Pgu/+ versus Pgu/Pgu p < 0.001), but there was no significant change in the frequency of sIPSCs (Pgu/+ versus Pgu/Pgu p = 0.3).

FIGURE 4.

Increased frequency and amplitude of sIPSCs and reduced AP firing rates in cerebellar Purkinje cells from Pgu mice in the cerebellar slice. Ai, representative traces from cerebellar Purkinje cells show sIPSCs in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice and block of sIPSCs in a Pgu/Pgu mouse with bicuculline (10 μm). Data were recorded in the presence of NBQX (10 μm). Holding potential was −60 mV. Scale bar, 50 pA, 200 ms. Aii, frequency of sIPSCs in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice is shown (+/+ 1.67 ± 0.24 Hz, n = 13 versus Pgu/+ 2.84 ± 0.34 Hz, n = 14, p = 0.008; +/+ versus Pgu/Pgu 3.50 ± 0.45 Hz, n = 20, p = 0.003). Aiii, amplitude of sIPSCs in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice (+/+ 38.27 ± 0.37 pA, n = 13 versus Pgu/+ 46.22 ± 0.35 pA, n = 14, p < 0.0001; +/+ versus Pgu/Pgu 57.77 ± 0.32 pA, n = 20, p = 0.001). Bi, frequency of sIPSCs (ctrl) compared with mIPSCs (+ttx) recorded in the presence of NBQX (10 μm) in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice frequency is shown (+/+ sIPSCs 1.90 ± 0.64 Hz, n = 6 versus mIPSCs 1.83 ± 0.60 Hz, n = 6, p = 0.21; Pgu/+ sIPSCs 3.15 ± 0.53 Hz, n = 7 versus mIPSCs 2.99 ± 0.43 Hz, n = 7, p = 0.8; Pgu/Pgu sIPSCs 3.57 ± 0.65 Hz versus mIPSCs 2.67 ± 0.50 Hz, n = 8, p = 0.007). Bii, amplitude of sIPSCs (ctrl) compared with mIPSCs (+ttx) in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice (+/+ sIPSCs 39.51 ± 0.47 pA, n = 6 versus mIPSCs 40.12 ± 0.49 pA, n = 6, p = 0.37; Pgu/+ sIPSCs 47.43 ± 0.45 pA, n = 7 versus mIPSCs 46.9 ± 0.47, n = 7, p = 0.415; Pgu/Pgu sIPSCs 57.4 ± 0.5 pA versus mIPSCs 54.2 ± 0.58 pA, n = 8, p < 0.0001). Ci, representative traces are shown of cell-attached action currents from cerebellar basket cells in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice. Holding potential, −60 mV. Scale bar, 100 pA, 100 ms. Cii, frequency of action currents from cerebellar basket cells in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice. Di, representative traces are shown of cell-attached action currents from cerebellar Purkinje cells in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice. Holding potential was −60 mV. Scale bar, 100 pA, 100 ms. Dii, frequency of action currents from cerebellar Purkinje cells in +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice is shown. Diii, interspike interval distribution for +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice. *, p = 0.05, **, p < 0.005.

Next we compared the amplitude and frequency of mIPSCs after blocking spontaneous action potential firing in basket cells. Experiments were performed in the presence of NBQX (10 μm) to block AMPA receptor-mediated events and TTX (1 μm) to block sodium channel-dependent action potentials. To eliminate cell-to-cell variability in responses and to ensure accurate comparisons between sIPSCs and mIPSCs, control data (sIPSCs, without TTX) were collected for each cell before the addition of TTX (mIPSCs). Under these conditions, mIPSCs recorded from +/+ and Pgu/+ mice were not statistically different compared with sIPSCs in frequency (Fig. 4Bi) or amplitude (Fig. 4Bii). These results suggest that the size and frequency of sIPSCs onto Purkinje cells in both +/+ and Pgu/+ are action potential-independent as neither was significantly affected by the addition of TTX.

In contrast, mIPSCs recorded from Pgu/Pgu mice, however, showed a significant reduction after TTX in both their frequency (Fig. 4Bi) and amplitude (Fig. 4Bii) compared with sIPSCs. Despite the small decrease in amplitude for mISPCS compared with sIPSCs recorded from Pgu/Pgu mice, mIPSCS from Pgu/Pgu mice are still significantly larger than mIPSCS recorded from both +/+ and Pgu/+ mice (Pgu/Pgu versus +/+, p < 0.0001; Pgu/Pgu versus Pgu/+, p < 0.0001).

These results in both Pgu/Pgu and Pgu/+ mice are best explained by an increase in the excitability of the basket cell terminal as a whole, leading to an increase in the amplitude of IPSCs that does not require action potentials. Additionally, Pgu/Pgu mice also appear to have an increase in the number of action potentials reaching the basket cell terminal, as there was a significant reduction in mIPSC frequency compared with sIPSC frequency, suggesting that alteration of Kv1 current at the terminal allows spontaneous spiking of basket cell pinceaus.

Unaffected Basket Cell Firing Rate and Reduced Purkinje Cell Action Potential Firing Frequency in Pgu Mice

An alternative mechanism that could account for the increase in sIPSCs in Purkinje cells of Pgu mutants is an increase in the intrinsic firing rate of basket cells. Cell-attached recordings from basket cell bodies were used as a minimally invasive means to monitor the spiking behavior of +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice. Under voltage-clamp cell-attached configuration, each spike was registered as a compound current with inward and outward deflections from the base line (Fig. 4Ci). There was no statistical difference in the frequency of recorded spikes from basket cell bodies between all three genotypes (+/+ 13.89 ± 1.42 Hz, n = 5 versus Pgu/+ 14.60 ± 1.82 Hz, n = 5, p = 0.77; +/+ versus Pgu/Pgu 13.75 ± 1.71 Hz, n = 5, p = 0.95; Pgu/+ versus Pgu/Pgu p = 0.74, Fig. 4Cii). This observation is in line with direct electrophysiological evidence showing an absence of Kv1.2 mediated current at the basket cell soma (25, 26) and also suggests that spatially segregated Kv1.2 α-subunit-containing channels within the nerve terminal can compartmentalize their distal actions to the pinceau independent of the somatic excitability and firing behavior of basket cells, as it does in other synapses (27). An increase in the frequency and amplitude of sIPSCs without any change in the basket cell intrinsic spiking rate suggests that effects of the Pgu mutation are restricted to the presynaptic terminal.

To determine whether the increased GABAergic transmission from basket cells to Purkinje cells in Pgu mutants has an effect on Purkinje cell spiking behavior, we conducted non-invasive cell-attached voltage-clamp recordings to observe the firing patterns of +/+, Pgu/+, and Pgu/Pgu mice (Fig. 4Di). The frequency of spikes in +/+ mice was significantly higher than in Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice (+/+ 18.96 ± 1.99 Hz, n = 17 versus Pgu/+ 9.93 ± 1.65 Hz, n = 12, p = 0.002; +/+ versus Pgu/Pgu 8.93 ± 0.89 Hz, n = 14, p = 0.0001, Fig. 4Dii). The raw frequencies of spikes were not significantly different between Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice (p = 0.6). To further quantify the effects of the Pgu mutation on Purkinje cell spike output, we looked at the inter-spike interval distribution for the three different genotypes. These distribution histograms clearly display a Gaussian-like distribution with a long tail for +/+ and Pgu/+ mice. The Pgu/Pgu mice, however, had a much more irregular ISI distribution (Fig. 4Diii) that highlighted a more variable and sparse spiking pattern for these Purkinje cells. These findings demonstrate that the increase in GABAergic tone from basket cells to Purkinje cells, due to the Kv1.2 I402T Pgu mutation, alters the sole efferent output of the cerebellum.

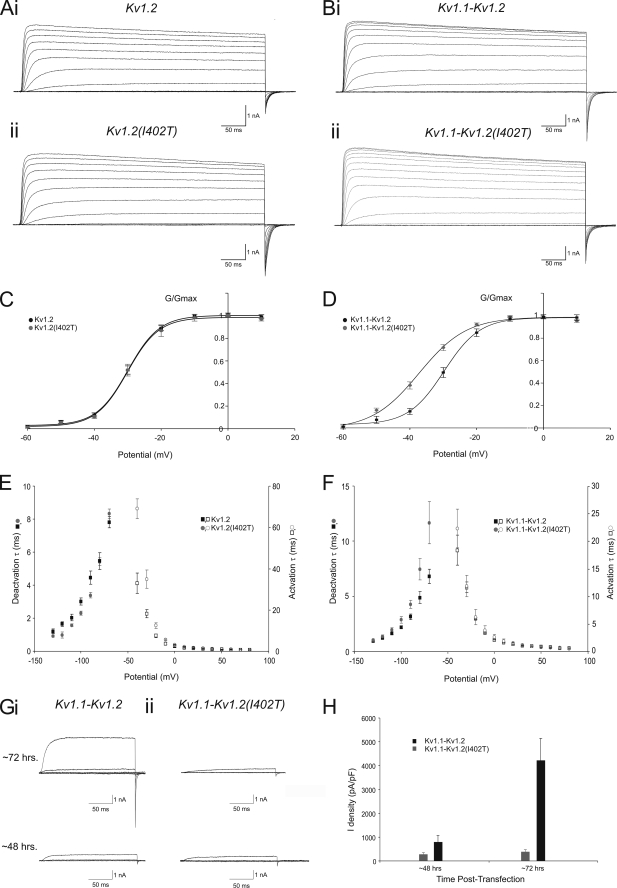

The I402T Missense Mutation Significantly Reduces the Amount of Functional Kv1.2 α-Subunit-containing Channels but Only Induces Subtle Changes in Their Biophysical Properties

To investigate possible changes in Kv1.2 channel function due to the I402T missense mutation in the highly conserved S6 domain, CHO cells were transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein-tagged cDNAs coding for either wild-type Kv1.2 α-subunits or Kv1.2 α-subunits that contain the I402T missense mutation (Kv1.2(I402T)). CHO cells were chosen for these experiments as they have very little native outward potassium current (28). Beginning 48 h after transfection, visually healthy CHO cells exhibiting uniform fluorescence were voltage-clamped in the whole cell configuration. Currents were obtained from a holding potential of −90 mV, through a series of incrementing voltage steps (+10 mV) up to +60 mV (Fig. 5A). To reduce current amplitude and help ensure the quality of the voltage clamp, low internal potassium was used (32.5 mm) in combination with the non-permeable cationic ion N-methyl-d-glucamine. Even in these conditions some very large currents were elicited (>75 nA) that made accurate voltage control impossible. To avoid voltage-clamp errors, only cells that had potassium currents that were <20nA were used for voltage dependence and kinetic analysis.

FIGURE 5.

The Kv1.2 I402T missense mutation results in gating, kinetic, and surface expression level changes in homomeric and heteromeric channels that contain the Kv1. 2(I402T) α-subunit in CHO cells. A, shown are representative currents, recorded from a CHO cell expressing either Kv1.2 (Ai) or Kv1.2(I402T) (Aii) 48 h post-transfection using +10-mV incrementing steps to +60 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV. Scale bar, 1 nA, 50 ms. B, representative currents, recorded from a CHO cell expressing either Kv1.1 (Bi) and Kv1.2 or Kv1.1 and Kv1.2(I402T) (Bii) 48 h post-transfection using +10-mV incrementing steps to +60 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV. Scale bar, 1 nA, 50 ms. C, shown are the mean g/gmax-voltage relationship for whole cell, voltage-clamped CHO cells expressing Kv1.2 (n = 10, black squares) or Kv1.2(I402T) (n = 10, grey circles). The Boltzmann functions shown superimposed on the data points gave the V½ and slope values quoted under “Results.” D, shown are the mean g/gmax-voltage relationship for whole cell, voltage-clamped CHO cells expressing Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 (n = 10, black squares) α-subunits or Kv1.1 and Kv1.2(I402T) (n = 10, grey circles). The Boltzmann functions shown superimposed on the data points gave the V½ and slope values quoted under “Results.” E, shown are the mean activation and deactivation time constants from whole cell, voltage-clamped CHO cells expressing Kv1.2 (n = 8, black squares) or Kv1.2(I402T) (n = 8, grey circles). F, shown are the mean activation and deactivation time constants from whole cell, voltage-clamped CHO cells expressing Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 (n = 8, black squares) or Kv1.1 and Kv1.2(I402T) (n = 8, grey circles). G, shown are representative currents, recorded from CHO cells expressing either Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 (Gi) or Kv1.1 and Kv1.2(I402T) (Gii) ∼48 and ∼72 h post-transfection using +10-mV incrementing steps to −30 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV. Scale bar, 1 nA, 50 ms. H, shown are mean maximum current density from whole cell, voltage-clamped CHO cells expressing Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 (n = 8, black bars) or Kv1.1 and Kv1.2(I402T) (n = 8, grey bars) after ∼48 and ∼72 h post-transfection.

To establish their G/Gmax-voltage(V) relationships, conductance (G) was calculated for each cell by dividing the individual steady state currents by the driving force (V-Erev), which was measured with tail currents. The conductance was then plotted against voltage and fit with a first-order Boltzmann function to determine Gmax. For whole cell currents recorded from CHO cells transfected with wild-type Kv1.2 α-subunits, the curve-fitting yielded a V½ = −29.9 ± 0.3 mV (n = 10; Fig. 5C) and slope factor of 4.7 ± 0.2 mV (n = 12). Threshold for current activation was approximately −60 mV. Kv1.2(I402T) mutant channels displayed virtually identical properties to wild-type channels (V½ = −30.3 mV, p = 0.57; slope factor of 4.4 ± 0.5mV, p = 0.60; threshold for current activation was approximately −60 mV (n = 10), as illustrated by the overlap of their respective G/Gmax-V curves (Fig. 5C). Potassium current activation kinetics were voltage-dependent and well fitted with a single exponential function (not shown) (Fig. 5E). The mean potassium current activation time constants were significantly slower between −40 and +20 mV (e.g. at −40 mV: 33.0 ± 4.9 ms for Kv1.2, n = 5 versus 69.1 ± 4.8 ms for Kv1.2(I402T), n = 8, p = 0.004) but not significantly different above +20 mV (e.g. at +40 mV: 1.03 ± 0.11 ms Kv1.2, n = 9 versus 1.02 ± 0.05 ms for Kv1.2(I402T), n = 10, p = 0.2, Fig. 5E). Deactivation kinetics were studied by depolarizing CHO cells from −100 to +30 mV and then stepping back down to hyperpolarized levels, starting at −130 mV, in incrementing steps (+10 mV) to −70 mV. The resulting tail currents were rapid, voltage-dependent, and well fitted with a single exponential (Fig. 5E). The mean deactivation time constants were significantly faster for the steps between −120 and −90 mV (e.g. −100 mV: 3.06 ± 0.2 ms for Kv1.2, n = 7 versus 2.31 ± 0.1ms for Kv1.2(I402T), n = 7, p = 0.02) but not significantly different for the steps to −130, −80, and −70 mV (e.g. −70 mV: Kv1.2 7.8 ± 0.3 ms, n = 7 versus Kv1.2(I402T) 8.3 ± 0.3 ms, n = 7, p = 0.27). The tail current reversed at approximately −60 mV for both Kv1.2 and Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit containing channels.

Cerebellar basket cell pinceau terminals are thought to express potassium channels that contain only Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 α-subunits (18). To study the possible effects of the Kv1.2 I402T missense mutation on Kv1.1-Kv1.2 heteromeric channels, we simultaneously transfected CHO cells with enhanced green fluorescent protein-tagged cDNAs coding for either Kv1.2 or Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunits and DsRed-tagged cDNAs coding for the Kv1.1 α-subunit, with equal amounts of cDNA for each specific α-subunit. Beginning 48 h after transfection, CHO cells exhibiting uniform fluorescence for both enhanced green fluorescent protein and DsRed were voltage-clamped in the whole cell configuration, and currents were evoked using the same protocol described previously (Fig. 5B). For whole cell currents recorded from CHO cells transfected with wild-type Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 α-subunits, the mean G/Gmax -V curve was fitted with a single Boltzmann function with a V½ = −37.2 ± 0.7mV (n = 9; Fig. 5D) and slope factor of 7.08 ± 1.0 mV (n = 9). Threshold for current activation was approximately −60 mV. For currents generated by Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunits, we found a significant leftward shift in their G/Gmax -V curve (∼8 mV) and 3-mV reduction in the slope factor (V½ = −29.6 ± 0.3 mV, p < 0.0001; slope factor of 5.49 ± 0.3 mV, p = 0.0375, n = 10, Fig. 5D). The activation time constants were not significantly different between Kv1.1-Kv1.2 α-subunit and Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit containing heteromeric channels at all voltages tested (e.g. at −40 mV: 18.4 ± 2.7 ms for Kv1.1-Kv1.2, n = 7 versus 22.4 ± 3.5 ms for Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T), n = 8, p = 0.4; e.g. at +40 mV: 1.02 ± 0.03 ms for Kv1.1-Kv1.2, n = 7 versus 1.06 ± 0.1 ms for Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T), n = 8, p = 0.8), but deactivation time constants were significantly different between Kv1.1-Kv1.2 α-subunit and Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit containing heteromeric channels for the steps below −100 mV (e.g. −110 mV: 1.66 ± 0.2 ms for Kv1.1-Kv1.2, n = 8 versus 1.97 ± 0.5 ms for Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T), n = 7, p = 0.2; e.g. −70 mV: Kv1.1-Kv1.2 6.8 ± 1.83 ms, n = 8 versus Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) 11.7 ± 5.1 ms, n = 7, p = 0.04, Fig. 5F). The reversal potential of tail currents was approximately −60 mV for both Kv1.1-Kv1.2 α-subunit and Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit-containing heteromeric channels. It should be noted that the activation threshold for homo- or heteromeric Kv1 channels in CHO cells is substantially more positive than that of the native channels in the basket cell terminal measured with direct patch clamp experiments (26). This is not unexpected as the exact stoichiometry of both the α- and β- subunits in native tissues likely differ from CHO cells and that the internal solution for recording CHO cells contained low potassium to reduce current amplitude and ensure adequate voltage clamp.

The leftward shift in G/Gmax-V relationship in Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) channels and slower deactivation kinetics would predict more effective repolarization of the membrane potential at the nerve terminal and, hence, a reduction in GABA release, opposite to what we have observed at the basket cell-Purkinje cell synapse. To search for an alternative mechanism, we next explored whether this missense mutation would affect the cell surface expression of these heteromeric channels. To quantify the effect of the I402T missense mutation on cell surface expression we compared the mean current density between CHO cells expressing Kv1.1-Kv1.2 α-subunits and Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunits. Current density for individual cells was measured as the maximal current in a given cell divided by its capacitance. The same sets of cultured CHO cells were examined 48 and 72 h after they were transfected (Fig. 5Gi). We found the current density for the two populations of CHO cells after 48 h was not significantly different (Kv1.1-Kv1.2 776.8 ± 301.3 pA/pF, n = 8 versus Kv.1-Kv1.2(I402T) 262.3 ± 61.1 pA/pF, n = 7, p = 0.17; Fig. 5Gii). However, 72 h after transfection, current density was approximately an order of magnitude greater in Kv1.1-Kv1.2 α-subunit containing CHO cells (Kv1.1-Kv1.2: 4172.3 ± 968.7 pA/pF, n = 8 versus Kv.1-Kv1.2(I402T): 387.3 ± 87.8 pA/pF, n = 7, p = 0.006). Furthermore, current density values for Kv1.1-Kv1.2 α-subunit containing CHO cells was significantly higher at 72 h post transfection than at 48 h (p = 0.005), whereas the current density for Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit-containing CHO cells was not significantly different (p = 0.27). Taken together, these results indicate that this mutation produces subtle changes in the biophysical properties of homomeric and heteromeric Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunit containing channels, but dramatically decreases the number of functional channels, therefore, reducing the density of Kv1 channel current.

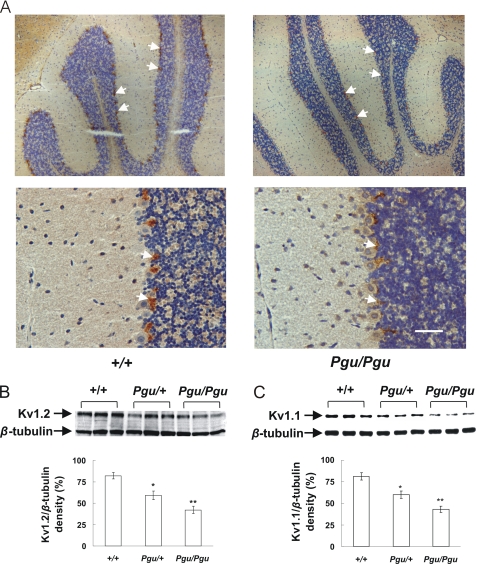

Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 Protein Levels Are Decreased in the Cerebellum of Pgu Mice

We next wanted to determine whether Kv1.2 protein levels were similarly reduced in the cerebellum of Pgu mutants. The overall cytoarchitecture and cerebellar morphology of Pgu adult mouse brain appeared normal, but the intensity of Kv1.2 antibody staining within the cerebellum was significantly reduced in Pgu/Pgu mice compared with +/+ mice (Fig. 6A). Western blotting showed a decreased expression level of Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 proteins in cerebellum from adult Pgu mice (Fig. 6, B and C). Quantitative analysis of Kv1.2/β-tubulin and Kv1.1/β-tubulin densitometry revealed a significant reduction in Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 proteins of 28 and 26% in Pgu/+ and 48 and 47% in Pgu/Pgu mice, respectively, compared with the wild-type level. The decreased levels of Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 proteins in the cerebellum were not significantly different between Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mutants (p = 0.075, p = 0.068 respectively). This result is in line with our observations that there is a significant decrease in the current density of Kv.1-Kv1.2(I402T) channels expressed in CHO cells.

FIGURE 6.

Reduced expression level of Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 proteins in the cerebellum of Pgu mice. A, polyclonal antibody rabbit anti-Kv1.2 staining of the cerebellum of +/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice, indicated by white arrows, showed a decreased intensity of Kv1.2 antibody staining, within the basket cell axon plexus terminals surrounding the Purkinje cells in Pgu/Pgu mice (the staining in Pgu/+ mice is not shown). B and C, Western blot of the protein extracted from the cerebellum of the adult Pgu mice and +/+ controls and quantitative analysis of the Kv1.2 or Kv1.1/β-tubulin densitometer showed a significant reduction of Kv1.2 and Kv1.1 proteins in Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice by 28, 26, 48%, and 47%, respectively, compared with +/+ controls (mean ± S.E., n = 6 for each genotype. Kv1.2: +/+ 81.6 ± 3.69 versus Pgu/+ 58.8 ± 5.33, p = 0.024; +/+ versus Pgu/Pgu 42.5 ± 4.26, p = 0.0023. Kv1.1: +/+ 80.9 ± 4.03 versus Pgu/+ 59.6 ± 4.16, p = 0.032; +/+ versus Pgu/Pgu 42.8 ± 3.97, p = 0.0048). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. The scale bar indicates 50 μm.

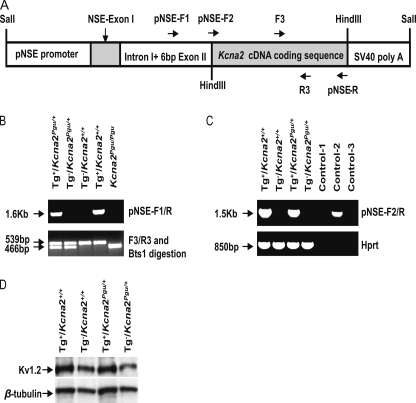

Increase in Expression of Kv1.2 Protein Partially Rescues the Impaired Motor Coordination in Pgu Mice

The Kcna2 Pgu mutation reduced the Kv1.2 protein level in the cerebellum and exhibited a phenotype characterized by chronic motor coordination deficits. To genetically confirm that the Kcna2 Pgu (Kv1.2 I402T) mutation contributes to the motor dysfunction in Pgu mice, we investigated whether the transgenic overexpression of a wild-type Kcna2 gene could reduce the motor incoordination in Pgu mice. We created a transgenic mouse line that carries exogenous mouse wild-type Kcna2 cDNA coding sequences under the control of the neuron-specific enolase (NSE) promoter. A schema of the DNA construct used for the production of the transgenic mice is shown in Fig. 7A. Genotype analysis showed incorporation of 1.6 kb of exogenous DNA containing Kcna2 cDNA coding sequences in transgenic-positive mice (Fig. 7B). Expression of the exogenous Kcna2 mRNA in the cerebellum of transgenic positive (Tg+) mice was verified by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 7C). Western blot demonstrated a higher level of Kv1.2 protein expression in the cerebellum of transgenic positive mice compared with control mice (Fig. 7D).

FIGURE 7.

Creation of Kcna2 transgenic mice. A, shown is a scheme of a full-length DNA construct used for the generation of transgenic mice showing regions of rat NSE promoter with NSE exon I, intron I, and 6 bp of exon II, wild-type mouse Kcna2 cDNA coding sequence, and a SV40 polyadenylation signal sequence. B, PCR amplification of genomic DNA using the specifically designed primer pair pNSE-F1 and pNSE-R yielded a 1.6-kb DNA product in transgenic positive mice. Genotyping of Kcna2 Pgu mutant was performed by PCR amplification of genomic DNA using the primer pair F3 and R3 followed by digestion of the PCR product with the Bts1 restriction enzyme, yielding DNA fragments of 539 and 466 bp in Pgu/+ mice, 539 bp in wild-type mice, and 466 bp in Pgu/Pgu mice. C, Kcna2 transgenic expression is shown. RNA from the cerebellum was used for RT-PCR analysis using the specific primers pNSE-F2 and pNSE-R for the transgenic Kcna2 mRNA. Transgenic Kcna2 mRNA was expressed in Tg+/Kcna2+/+ and Tg+/ Kcna2Pgu/+ mice but not in non-transgenic mice. Control-1 indicates a PCR reaction using Tg+/ Kcna2Pgu/+ RNA without reverse transcriptase. The genomic DNA from Tg+/ Kcna2Pgu/+ was used as a positive control in control-2. Control-3 is water. Hprt cDNA was amplified as a positive control for cDNA quality. D, shown is a Western blot analysis of cerebellum homogenates obtained from transgenic and non-transgenic wild-type and Kcna2 Pgu/+ mice. β-Tubulin III immunoreactivity was used to ensure that equal amounts of protein were loaded. The quantitative analysis of the Kv1.2/β-tubulin densitometer revealed that Kv1.2 protein in the cerebellum of Tg+/Pgu increased by 50% compared with Tg−/Pgu mice (mean ± S.E., Tg+/Pgu 96.22 ± 6.89, n = 4 versus Tg−/Pgu 64.13 ± 7.29, n = 4, p = 0.017). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

10-Week-old transgenic-positive Pgu/+ (Tg+/Kcna2Pgu/+; Tg+/Pgu), transgenic negative Pgu/+ (Tg−/Kcna2Pgu/+; Tg−/Pgu), and +/+ (Tg−/Kcna2+/+; Tg−/wt) littermates were examined in the accelerating rotarod, balance beam-walking, and footprint tests, which showed that Tg+/Pgu mice significantly improved their impaired motor coordination compared with Tg−/Pgu mice. The latency to fall from the accelerating rotarod significantly increased in Tg+/Pgu mice compared with Tg−/Pgu mice (Fig. 8A). The numbers of hind-foot slips (Fig. 8Bi) and the latency to traverse the beam (Fig. 8Bii) were significantly reduced in Tg+/Pgu mice compared with Tg−/Pgu mice. The hind-limb prints of Tg+/Pgu mice showed significant reduction in the span between toes 1 and 5, toes 2 and 4, toe 3, and the heel compared with Tg−/Pgu mice (Fig. 8Ci). The reduced stride length and stride width in Tg+/Pgu mice were not significantly different from Tg−/Pgu mice (Fig. 8Cii). There were no significant differences in the results of the footprint analysis between Tg+/Pgu mice and Tg−/wt controls. Tg+/Pgu mice exhibited significant improvement in motor coordination but still showed motor coordination deficits in the accelerating rotarod and balance beam-walking tests compared with Tg−/wt mice (Fig. 8, A and B). This suggests that the Kv1.2 gene underlies motor deficits in Pgu mutant mice, as the transgenic expression of the wild-type Kcna2 gene was able to partially rescue the impaired motor coordination in Pgu mice. However, higher expression of Kv1.2 may be required to override residual effects of mutant Kv1.2 channels to achieve a complete rescue.

FIGURE 8.

Transgenic wild-type Kcna2 cDNA partially rescues the motor incoordination in Pgu mice. A, latency to fall off the accelerating rotarod is shown. Results were averaged over three trials each day for three consecutive days. (supplemental Table 5). Hind-foot missteps on the balance beam (Bi) and latency to traverse the beam (Bii) are shown. (supplemental Table 5). Hind-limb footprint analysis of toe spread (Ci) and stride width and stride length (Cii) are shown. (supplemental Table 6). *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The amino acid residue I402 is located within the large cavity of the ion-conducting pore of the Kv1 potassium channel and is highly conserved in the Kv1 subfamily of mammals (Fig. 2C) and in the Kv channels of Drosophila melanogaster and squid (29–31). The analogous position, Ile-470, within the Shaker H4 channel has been widely studied due to the fact that mutation at this site can lead to changes in channel gating and kinetics (29, 30, 32). Surprisingly, we found that homomeric channels comprised of Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunits, expressed in CHO cells, showed subtle changes in their G/Gmax-V relationship and kinetics compared with wild-type homomeric Kv1.2 channels.

The Kv1.2 I402T substitution could affect the changes observed in Pgu mice in a number of other ways besides changing the gating and kinetic properties of the Kv1.2 α-subunit itself. These could include altering the density and location of Kv1.2 α-subunits in the basket cell terminal and/or perturbing the preferred stoichiometry of native Kv1.2 α-subunit containing channels. The total expression level of both Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 α-subunit protein in Pgu/+ and Pgu/Pgu mice was significantly reduced in the cerebellum by ∼30 and ∼50%, respectively, which correlates with the degrees of cerebellar ataxia exhibited by these genotypes. This could be the result of poor folding and/or low stability of the mutant protein as well as poor oligomerization of mutant subunits leading to retention within the ER and subsequent degradation (33, 34). This reduction in Kv1 protein level would have a dramatic effect on the ability of basket cell terminals to generate the necessary number of channels with the preferred stoichiometry (35), which is comprised solely of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 α-subunits. This dramatic reduction in potassium channel number would elevate the resting potential of the nerve terminal, which could have dramatic effects on transmitter release. Action potential-evoked release is extremely sensitive to background or residual Ca+2 in the terminal (36) and can be greatly facilitated by even small increases in membrane potential that allow voltage-sensitive cation channel opening and Ca+2 influx (37). The reduction in the total amount of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 α-subunit protein seen in the cerebellum is in line with the ∼10-fold reduction in current density in CHO cells transfected with Kv1.1-Kv1.2(I402T) versus Kv1.1-Kv1.2 cDNA. This finding illustrates that CHO cells struggle to incorporate potassium channels containing Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunits into the lipid bilayer. It is reasonable to suggest, therefore, that the highly regulated and controlled process of expression of potassium channels at the basket cell terminal would also be significantly affected by the presence of Kv1.2(I402T) α-subunits, resulting in perturbations in the location and density of potassium channels (38).

A major electrophysiological effect of the Kv1.2 I402T substitution in Pgu mice was an increase in both the frequency and the amplitude of Purkinje cell sIPSCs. These sIPSCs originate from GABAergic interneurons, including stellate and basket cells. Kv1.2 α-subunits have not been found in stellate cells (9) but are present primarily in the axonal structures of basket cells, with the highest concentrations in their terminals, where they are uniquely positioned to affect distal excitability (6–9). Electrophysiological recordings in mice ruled out any contribution of Kv1.2-mediated somatic potassium currents in either the presynaptic basket cell or the postsynaptic Purkinje cell (25, 26). We have also shown directly that the Kv1.2 I402T substitution does not alter the intrinsic spiking rate of basket cells. Kv1.2 subunits exert their effects at the basket cell terminal without affecting axonal repolarization (39); therefore, they are most likely involved in propagating action potentials along the presynaptic axon as well as clamping the terminal resting membrane potential, thereby controlling spike threshold and basal [Ca]i levels. These factors can effectively influence the probability that a vesicle will be released and its contents subsequently bound by a postsynaptic target, thereby increasing the strength of this tonic inhibitory synaptic connection, as seen in Pgu/Pgu mice. Consistent with this idea, blockade of low-threshold potassium currents in basket cell terminals has been shown to result in a 20–30-mV leftward shift in the activation of the remaining unblocked potassium current, resulting in an increase in the frequency and amplitude of sIPSCs (25, 26). Future studies involving the patch-clamping of the terminal itself, although extremely technically challenging, would be able to directly compare the changes in Kv1 terminal current due to the I402T substitution and make an even stronger argument for its role in the phenotypes observed in Pgu mice.

Changes in strength at a synaptic connection must in the end also modify the ability of that synapse to influence postsynaptic spike output for alterations in synaptic strength to be read out and transmitted further in the network. Ultimately, to influence the functioning of this cerebellar circuit, the increase in the synaptic strength of this tonic GABAergic connection must be able to alter the Purkinje cell spike output. Consistent with this, in the in vitro acute slice preparation, we showed that the Kv1.2 I402T substitution resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency as well as an overall broadening of the inter-spike interval distribution of the action potential firing of Purkinje cells. The Kv1.2 I402T substitution in Pgu mice perturbs and reduces in several ways the normal spike output of Purkinje cells, which encodes important timing information necessary for coordinated movement. It disrupts the normal ratio of excitatory and inhibitory tonic asynchronous conductances, which alters the subthreshold membrane potential at which the neuron is clamped and, therefore, the activation of the intrinsic conductances that generate the natural pace-making activity of the Purkinje cell. Also, the relationship between the inhibitory postsynaptic potential amplitude measured at the soma and the interspike interval prolongation is steep (11–13); therefore, the increase in the number and size of IPSPs reaching the soma of Purkinje cells in Pgu mice will act to effectively reduce spiking. As well as affecting the balance of asynchronous sIPSCs invading the Purkinje cell, it also alters the ratio of behaviorally relevant excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs generated by the feed-forward inhibitory circuit that impinge on Purkinje cells, effectively reducing the signal to noise ratio.

The cerebellum is involved in the regulation of the initiation and timing of movements and is important for maintaining balance and posture, and as such, it seems logical that the constellation of movement disorders associated with the Pgu mutation, which includes ataxia, myoclonic jerks, tremors and flattened posture, involve the cerebellum. However, even though Kv1.2 is most highly enriched in cerebellar basket cell terminals and is clearly important in normal cerebellar function and output, it is also expressed at lower levels throughout the central and peripheral nervous system (40). Cortical, subcortical, and peripheral dysfunction, due to the alteration of Kv1.2 channel function, location, and density, may also contribute to the observed motor disorders. To more accurately determine the level to which the cerebellum is involved in the Pgu phenotype, further experiments would need to be carried out, such as site-specific cerebellar rescue.

Kv1.2 subunits are colocalized with Kv1.1 subunits in the cerebellar basket cell axon plexus terminals and often form heteromeric channels (6, 7, 18). Kv1.1 missense mutations underlie human EA1 (16). Although electrophysiological changes in cerebellar Purkinje cells in Pgu mice resemble the electrophysiological changes described for the Kv1.1 V408A EA1 mutation knock-in mice (17), the neurobehavioral differences between these two channelopathies are remarkably distinct. The homozygous Kv1.1 V408A mutation is embryonic lethal, whereas the homozygous Kv1.2 I402T mutation is viable. Heterozygous Kv1.1 V408A/+ mice showed normal motor behavior in the accelerating rotarod and the balance beam tests, and their motor impairments had to be induced by the combination of injection of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol and exercise, whereas heterozygous Kv1.2 I402T/+ mice intrinsically exhibited chronic motor dysfunction. Similarly, Kcna2 null mice have greater seizure susceptibility and a lower life span than Kcna1 null mice (41, 42). These findings suggest that Kv1.2 subunits may play an important, if not more dominant, role than Kv1.1 in the control of cerebellar motor function during and after postnatal development, whereas Kv1.1 subunits are probably more important than Kv1.2 during early embryonic development. This is consistent with the first strong up-regulation of Kv1.2 expression in the second postnatal week (41, 43) and a strong transient embryonic expression of Kv1.1 (44).

Heterozygous Kv1.2 I402T (Pgu/+) mutants had chronic motor incoordination, whereas heterozygous Kv1.2 null mice appeared to have normal motor behavior despite a 50% reduction of Kv1.2 protein in the brain (41). Homozygous Kv1.2 I402T (Pgu/Pgu) mutants exhibited severe motor incoordination from P10, whereas homozygous Kv1.2 null mice do not show abnormal phenotype until P15 (41). This is similar to the dominant-negative effects of the Kv1.1 V408A EA1 mutation in the knock-in mouse (17). The embryonic lethality of the homozygous Kv1.1 V408A mutation limits the use of this model to further study the malfunction of Kv1 channels in vivo. The viability of homozygous Kv1.2 Pgu mutants, thus, provide an ideal mouse model for comprehensive in vivo study of this novel Shaker family voltage-gated potassium channelopathy and any related neurological disorders as well as potential strategies for treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Centre for Modeling Human Disease, directed by Janet Rossant and coordinated by Ann Flenniken, for producing the ENU mice and Sabine Cordes for helpful discussion and Zikai Zhou and Zhengping Jia for assistance with recombinant expression work in CHO cells.

This work was supported by Canadian Institute of Health Research Grants CIHR MOP-77809 (to J. C. R.) and MOP-143867and MOP-14692 (to L.-Y. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1–6.

- EA1

- type 1 episodic ataxia

- IPSC

- inhibitory postsynaptic current

- sIPSC

- spontaneous IPSC

- mIPSC

- miniature IPSC

- ATZ

- acetazolamide

- GABA

- γ-aminobutyric acid

- NSE

- neuron-specific enolase

- SNP

- single nucleotide polymorphism

- TTX

- tetrodotoxin

- pF

- picofarads

- NBQX

- 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione

- Mb

- megabase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hille B. (2001) Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, Sinauer, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trimmer J. S. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 10764–10768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drewe J. A., Verma S., Frech G., Joho R. H. (1992) J. Neurosci. 12, 538–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang P. M., Glatt C. E., Bredt D. S., Yellen G., Snyder S. H. (1992) Neuron 8, 473–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang P. M., Fotuhi M., Bredt D. S., Cunningham A. M., Snyder S. H. (1993) J. Neurosci. 13, 1569–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H., Kunkel D. D., Martin T. M., Schwartzkroin P. A., Tempel B. L. (1993) Nature 365, 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H., Kunkel D. D., Schwartzkroin P. A., Tempel B. L. (1994) J. Neurosci. 14, 4588–4599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNamara N. M., Muniz Z. M., Wilkin G. P., Dolly J. O. (1993) Neuroscience 57, 1039–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNamara N. M., Averill S., Wilkin G. P., Dolly J. O., Priestley J. V. (1996) Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 688–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng M., Tsaur M. L., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1994) J. Neurosci. 14, 2408–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaeger D., De Schutter E., Bower J. M. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 91–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaeger D., Bower J. M. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 6090–6101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter J. T., Alviña K., Womack M. D., Chevez C., Khodakhah K. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 9, 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton S. M., Bastian A. J. (2007) Cerebellum 6, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bower J. M. (2002) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 978, 135–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browne D. L., Gancher S. T., Nutt J. G., Brunt E. R., Smith E. A., Kramer P., Litt M. (1994) Nat. Genet. 8, 136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herson P. S., Virk M., Rustay N. R., Bond C. T., Crabbe J. C., Adelman J. P., Maylie J. (2003) Nat. Neurosci. 6, 378–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch R. O., Wanner S. G., Koschak A., Hanner M., Schwarzer C., Kaczorowski G. J., Slaughter R. S., Garcia M. L., Knaus H. G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27577–27581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes K. J., Strassle B. W., Monaghan M. M., Bekele-Arcuri Z., Matos M. F., Trimmer J. S. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 8246–8258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie G., Clapcote S. J., Nieman B. J., Tallerico T., Huang Y., Vukobradovic I., Cordes S. P., Osborne L. R., Rossant J., Sled J. G., Henderson J. T., Roder J. C. (2007) Genes Brain Behav. 6, 717–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mucke L., Masliah E., Johnson W. B., Ruppe M. D., Alford M., Rockenstein E. M., Forss-Petter S., Pietropaolo M., Mallory M., Abraham C. R. (1994) Brain Res. 666, 151–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klapdor K., Dulfer B. G., Hammann A., Van der Staay F. J. (1997) J. Neurosci. Methods 75, 49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zasorin N. L., Baloh R. W., Myers L. B. (1983) Neurology 33, 1212–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gancher S. T., Nutt J. G. (1986) Mov. Disord. 1, 239–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Southan A. P., Robertson B. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 948–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southan A. P., Robertson B. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 114–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dodson P. D., Forsythe I. D. (2004) Trends Neurosci. 27, 210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu S. P., Kerchner G. A. (1998) J. Neurosci. Res. 52, 612–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmgren M., Smith P. L., Yellen G. (1997) J. Gen. Physiol. 109, 527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Holmgren M., Jurman M. E., Yellen G. (1997) Neuron 19, 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhalla T., Rosenthal J. J., Holmgren M., Reenan R. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hackos D. H., Chang T. H., Swartz K. J. (2002) J. Gen. Physiol. 119, 521–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu J., Watanabe I., Gomez B., Thornhill W. B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39419–39427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurtley S. M., Helenius A. (1989) Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 5, 277–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manganas L. N., Trimmer J. S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29685–29693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felmy F., Neher E., Schneggenburger R. (2003) Neuron 37, 801–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Awatramani G. B., Price G. D., Trussell L. O. (2005) Neuron 48, 109–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shamotienko O., Akhtar S., Sidera C., Meunier F. A., Ink B., Weir M., Dolly J. O. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 16766–16776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan Y. P., Llano I. (1999) J. Physiol. 520, 65–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arroyo E. J., Xu Y. T., Zhou L., Messing A., Peles E., Chiu S. Y., Scherer S. S. (1999) J. Neurocytol. 28, 333–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brew H. M., Gittelman J. X., Silverstein R. S., Hanks T. D., Demas V. P., Robinson L. C., Robbins C. A., McKee-Johnson J., Chiu S. Y., Messing A., Tempel B. L. (2007) J. Neurophysiol. 98, 1501–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smart S. L., Lopantsev V., Zhang C. L., Robbins C. A., Wang H., Chiu S. Y., Schwartzkroin P. A., Messing A., Tempel B. L. (1998) Neuron 20, 809–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu H., Dixon J. E., Barry D. M., Trimmer J. S., Merlie J. P., McKinnon D., Nerbonne J. M. (1996) J. Gen. Physiol. 108, 405–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallows J. L., Tempel B. L. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 5682–5691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.