Abstract

Aseptic loosening of orthopaedic implants is induced by wear particles generated from the polymeric and metallic components of the implants. Substantial evidence suggests that activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) may contribute to the biological activity of the wear particles. Although pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) produced by Gram-positive bacteria are likely to be more common in patients with aseptic loosening, prior studies have focused on LPS, a TLR4-specific PAMP produced by Gram-negative bacteria. Here we show that both TLR2 and TLR4 contribute to the biological activity of titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris. In addition, lipoteichoic acid, a PAMP produced by Gram-positive bacteria that activates TLR2, can, like LPS, adhere to the particles and increase their biological activity, and the increased biological activity requires the presence of the cognate TLR. Moreover, three lines of evidence support the conclusion that TLR activation requires bacterially derived PAMPs and that endogenously produced alarmins are not sufficient. First, neither TLR2 nor TLR4 contribute to the activity of “endotoxin-free” particles as would be expected if alarmins are sufficient to activate the TLRs. Second, noncognate TLRs do not contribute to the activity of particles with adherent LPS or lipoteichoic acid as would be expected if alarmins are sufficient to activate the TLRs. Third, polymyxin B, which inactivates LPS, blocks the activity of particles with adherent LPS. These results support the hypothesis that PAMPs produced by low levels of bacterial colonization may contribute to aseptic loosening of orthopaedic implants.

Keywords: Bone, Inflammation, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Pathogen-associated Molecular Pattern (PAMP), Toll-like Receptors (TLR)

Introduction

Osteoimmunology is a newly emerging field that refers to bi-directional interactions between the skeletal system and the immune system (1). One example of regulation of the skeletal system by the immune system is inflammatory osteolysis, which is the local bone loss induced by inflammation in response to pathogens or nonpathogenic stimuli (1). Inflammatory osteolysis in response to either pathogens or nonpathogenic stimuli can contribute to loosening of orthopaedic implants and the resultant need to replace the implant. For example, implant infection is a devastating complication that often necessitates implant removal and long term intravenous treatment with antibiotics (2). In contrast, “aseptic loosening” results from inflammation induced by polymeric and metallic wear particles derived from the implant components in the absence of any clinical signs of infection (3, 4). The primary events involved in this process include: phagocytosis of the wear particles by macrophages; activation of the macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines; stimulation of bone resorptive cytokines, such as RANKL, in response to the pro-inflammatory cytokines; stimulation of osteoclast differentiation by the resorptive cytokines; and local osteolysis caused by the increased number of osteoclasts (3–5).

Subclinical levels of bacteria may contribute to wear particle-induced inflammation, and therefore aseptic loosening may result from inflammatory osteolysis caused by a combination of nonpathogenic and pathogenic stimuli (6–11). For example, the rate of aseptic loosening is reduced by prophylactic antibiotics (12), and we and many other investigators have shown that adherent LPS increases the biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles both in cell culture and in animal models (10). Moreover, detectable levels of LPS exist in peri-prosthetic tissue of a subset of aseptic loosening patients (13), and LPS accumulates in the tissue surrounding implanted wear particles (14, 15). We and others have also showed that TLR4,2 the primary receptor for LPS, contributes to the biological activity of wear particles in both cell culture and murine model systems (16, 17). Consistent with this, macrophages in peri-prosthetic tissue of patients with aseptic loosening express TLR4 (18–20) as well as its co-receptor, CD14 (21). Despite those findings, it is likely that PAMPs other than LPS are more common in patients with aseptic loosening because a Gram-positive biofilm exists on many of their implants (22–25). Macrophages in peri-prosthetic tissue express a complete panel of TLRs, including the primary receptors for most PAMPs (18–20). Although PAMPs other than LPS have not previously been studied on orthopaedic wear particles, lipoteichoic acid (LTA), a PAMP that activates TLR2 and is a major constituent of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria, can adhere to other materials and retain its biological activity (26). The goals of this study were therefore to determine whether PAMPs other than LPS, such as LTA, increase the biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles and to determine whether the effects are due to TLR activation by the adherent PAMPs. For this purpose, we compared responses in wild type mice, TLR2−/− mice, TLR4−/− mice, and mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4 as well as in macrophages isolated from each type of mouse. Initial experiments measured the biological activity of titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris. To examine the effects of specific bacterial PAMPs, we also measured the biological activity of titanium particles with adherent LTA and titanium particles with adherent LPS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris (34 endotoxin units/109 particles) were obtained from Johnson Matthey (Ward Hill, MA; catalogue number 00681, lot F06Q16) as we have previously described (27). “Endotoxin-free” titanium particles (<0.3 endotoxin unit/109 particles) were prepared without altering their size or shape as previously described (27). Titanium particles with adherent LPS (15 endotoxin units/109 particles) or adherent LTA were prepared by incubating endotoxin-free particles with highly purified 50 μg/ml LPS from Escherichia coli (0111:B4) or 500 μg/ml LTA from Staphylococcus aureus (both from InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for 4 days in, respectively, PBS containing 1.1 mm CaCl2 (28), or PBS without divalent cations. Particles with adherent PAMPs were washed 10 times in PBS with or without CaCl2 to remove any unbound PAMP. Adherent LPS on the particles was measured using the high sensitivity version of the chromogenic limulus amebocyte lysate assay with all of our technical precautions (29). All of the cell culture media and supplements were tested for LPS (29) and were from lots that contained the lowest amount of LPS available.

TLR2−/− and TLR4−/− mice were obtained from S. Akira (30, 31). Mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4 were generated in house (32, 33). Mouse genotypes were confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA isolated from tail clips (supplemental Fig. S1A). Wild type C57BL/6 mice matched for genetic background, age, and gender were obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). All of the animal experiments were approved by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Particle-induced osteolysis was assessed as previously described (34). For this purpose, 8 × 108 titanium particles suspended in 40 μl of PBS were implanted on the parietal bones of 6–8-week-old female mice, and osteolytic areas were quantified after 7 days by histomorphometry of microradiographs (Faxitron model 8050-10).

Bone marrow macrophages were isolated by differential adherence to tissue culture plastic as previously described (35). Thus, marrow cells (3.4 × 105 cells/cm2) were cultured for 24 h in serum-containing medium supplemented with either macrophage colony-stimulating factor (10 ng/ml; catalogue number 416-ML, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or 20% L929 fibroblast-conditioned medium harvested after 2–3 days of culture. Nonadherent cells were plated (2 × 105 cells/cm2) in fresh tissue culture dishes and cultured in serum-containing medium supplemented with either macrophage colony-stimulating factor or L929-conditioned medium. After 72 h, nonadherent cells were removed by rinsing twice with serum-free medium, and the adherent cells were cultured in fresh serum-containing medium supplemented with either macrophage colony-stimulating factor or L929-conditioned medium for 20–24 h. Adherent cells were then incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of 6.6 × 107 titanium particles/cm2, heat-killed E. coli K12 (3.3 × 106/ml; Invitrogen), or IL-1β (10 ng/ml; R & D Systems) as previously described (35). RNA was isolated using the ToTALLY RNA kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), and TNFα mRNA was measured by real time RT-PCR, using standard curves as we previously described (35, 36). TNFα mRNA levels were normalized to levels of GAPDH mRNA. The phenotype of macrophages isolated from the single and double knock-out mice was confirmed by incubation with soluble LPS, LTA, heat-killed E. coli, or IL-1β, as a positive control (supplemental Fig. S1B).

RAW264.7 macrophages (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in Petri dishes as previously described (35). For experiments, nonadherent cells were plated (4.1 × 104 cells/cm2) in tissue culture dishes and cultured in serum-containing medium. The following day, the cells were 60–70% confluent, and they were incubated for 90 min in the absence or presence of titanium particles (3.4 × 106 particles/cm2 unless otherwise indicated) or the indicated concentrations of heat-killed E. coli K12 (Invitrogen) or heat-killed E. coli 0111:B4 (InVivogen) as previously described (35). In selected experiments, the indicated concentrations of polymyxin B (Sigma) were preincubated with the cells for 30 min prior to stimulation with particles or bacteria. The TNFα levels secreted into the medium were measured as previously described (16).

All of the cell culture experiments were repeated for the indicated number of times, and the results are presented as the means + S.E. of multiple experiments. The results of in vivo experiments are reported as the means of individual parietal bones + S.E. The statistical analyses were by one-way repeated measures analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc tests (StatView 3.0, SPSS).

RESULTS

Biological Responses to Particles with Adherent Bacteria and to Endotoxin-free Particles

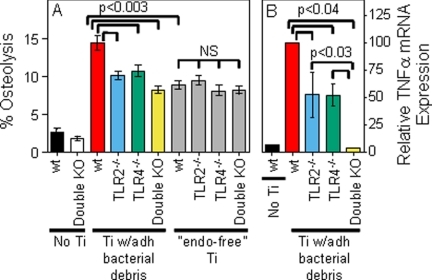

We have previously shown that the biological responses to titanium particles with adherent bacteria are reduced in mice with an inactivating mutation in TLR4 as well as in macrophages isolated from those mice (16). The current study confirmed this finding in TLR4−/− mice and extended it to examine TLR2−/− mice as well as double knock-out mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4. In the in vivo murine calvarial model of particle-induced osteolysis, particles with adherent bacterial debris induced significantly less osteolysis in TLR2−/− or TLR4−/− mice than in wild type mice (compare blue and green bars with red bar in Fig. 1A). Similarly, macrophages isolated from either TLR2−/− or TLR4−/− mice show significantly less TNFα mRNA induction in response to these particles than do wild type macrophages (compare blue and green bars with red bar in Fig. 1B). Moreover, macrophages lacking both TLR2 and TLR4 show significantly less TNFα mRNA induction than macrophages isolated from either of the single knock-out mice (compare yellow bar with blue and green bars in Fig. 1B). These cell culture experiments focused on TNFα because it is produced more rapidly than other pro-inflammatory cytokines and is the pro-inflammatory cytokine that has most conclusively been linked to aseptic loosening (reviewed in Ref. 35). We have previously demonstrated that the cell culture effects of the particles with adherent bacterial debris are not caused by release of LPS from the particles (35). The cell culture and in vivo results both show that TLR2 and TLR4 contribute to the biological activity of orthopaedic particles with adherent bacterial debris.

FIGURE 1.

Biological responses induced by titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris or by endotoxin-free titanium particles. A, osteolysis was measured in wild type mice, TLR2−/− mice, TLR4−/− mice, or double knock-out mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4. The results (means ± S.E. of 36–46 parietal bones/group) are presented as percentages of parietal bone contained within osteolytic regions. B, TNFα mRNA expression was measured in bone marrow macrophages isolated from wild type mice, TLR2−/− mice, TLR4−/− mice, or double knock-out mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4. The results (means ± S.E. of five experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα expression following incubation of wild type macrophages with titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris. Ti, titanium; wt, wild type; KO, knock-out; adh, adherent; “endo-free”, endotoxin-free; NS, not significant.

We have also previously shown that endotoxin-free titanium particles induce less osteolysis than the titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris (15, 16, 37). The current study confirmed those findings and demonstrated that the in vivo biological activity of the endotoxin-free particles does not depend on TLR2 and/or TLR4 (gray bars in Fig. 1A). Similar experiments were not possible in cell culture because the endotoxin-free particles do not induce significant responses by the bone marrow macrophages (compare gray and black bars in Figs. 2 and 3, A and B) (16, 38). Nonetheless, the in vivo experiments show that neither TLR2 nor TLR4 are required for the biological activity of the endotoxin-free particles.

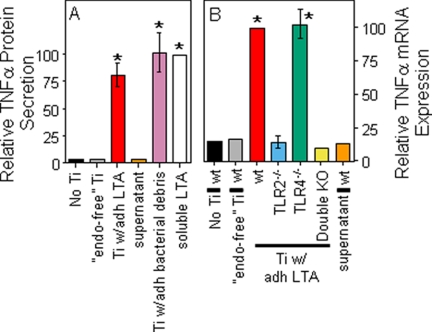

FIGURE 2.

Biological responses induced by titanium particles with adherent LTA. Control stimuli included the supernatant obtained by centrifuging the titanium particles with adherent LTA. A, TNFα protein secretion was measured in cultures of RAW264.7 cells. The results (means ± S.E. of three experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα protein secretion following stimulation with soluble LTA (S. aureus, 2 μg/ml). The asterisks denote p < 0.001 compared with groups without asterisks. B, TNFα mRNA expression was measured in bone marrow macrophages isolated from wild type mice, TLR2−/− mice, TLR4−/− mice, or double knock-out mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4. The results (means ± S.E. of three experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα expression following stimulation with titanium particles with adherent LTA. The asterisks denote p < 0.001 compared with groups without asterisks. Ti, titanium; wt, wild type; KO, knock-out; adh, adherent; “endo-free”, endotoxin-free.

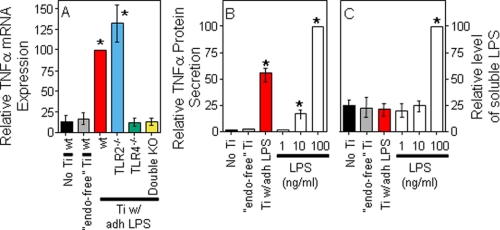

FIGURE 3.

Biological responses induced by titanium particles with adherent LPS. A, TNFα mRNA expression was measured in bone marrow macrophages isolated from wild type mice, TLR2−/− mice, TLR4−/− mice, or double knock-out mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4. The results (means ± S.E. of three experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα expression following stimulation with titanium particles with adherent LPS. The asterisks denote p < 0.005 compared with groups without asterisks. B and C, TNFα protein and soluble LPS were measured following incubation of RAW264.7 cells with endotoxin-free titanium particles, titanium particles with adherent LPS, or highly purified soluble LPS (E. coli 0111:B4; InvivoGen). The results (means ± S.E. of three experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα protein (B) or soluble LPS (C) following stimulation of RAW264.7 cells with 100 ng/ml LPS. The asterisks denote p < 0.001 compared with groups without asterisks. Ti, titanium; wt, wild type; KO, knock-out; adh, adherent; “endo-free”, endotoxin-free.

Biological Responses to Particles with Adherent PAMPs

Particles with adherent LTA induced significantly larger TNFα responses than endotoxin-free particles from both RAW264.7 macrophages and wild type bone marrow macrophages (compare red bars with gray bars in Fig. 2). The magnitude of this response is similar to that induced by particles with adherent bacterial debris or by 2 μg/ml of soluble LTA (purple and white bars in Fig. 2A). Moreover, the response is due to adherent rather than unbound LTA because the particle-free supernatant obtained by centrifugation of the particle suspension induced negligible responses (orange bars in Fig. 2). Finally, this response depends on TLR2 because it does not occur in macrophages from TLR2−/− mice (blue bar in Fig. 2B), whereas TLR4 deficiency does not affect the response (green bar in Fig. 2B). The results in this paragraph show that adherent LTA increases the biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles by activating TLR2.

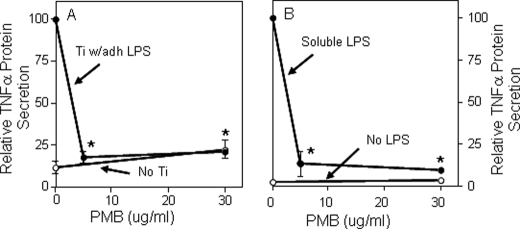

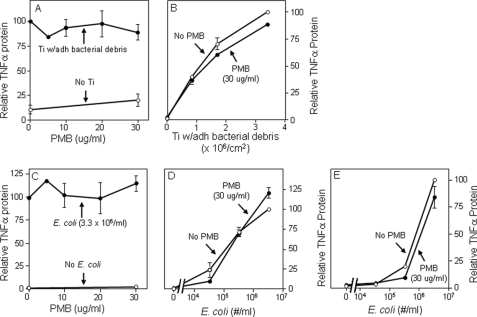

Particles with adherent LPS also induced significantly larger TNFα responses than endotoxin-free particles from both wild type bone marrow macrophages and RAW264.7 macrophages (compare red bars with gray bars in Figs. 3, A and B). The magnitude of this response is similar to that induced by 100 ng/ml of soluble LPS (white bars in Fig. 3B). Moreover, the response is not due to release of LPS from the particles during the experiments because particles with adherent LPS induced substantial TNFα production (red bar in Fig. 3B) but did not release detectable amounts of LPS into the culture media (red bar in Fig. 3C). Finally, this response depends on TLR4 because it does not occur in macrophages from TLR4−/− mice (green bar in Fig. 3A), whereas TLR2 deficiency does not affect the response (blue bar in Fig. 3A). Polymyxin B binds and inactivates LPS (39–41). We found that polymyxin B blocks the biological activity of particles with adherent LPS (Fig. 4A) and, as expected, of soluble LPS (Fig. 4B). The results in this paragraph show that adherent LPS increases the biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles by activating TLR4. In contrast to the results in Fig. 4A, we and others found that polymyxin B does not substantially inhibit the biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles with adherent bacterial debris (Fig. 5, A and B) (42). However, we also found that polymyxin B does not substantially inhibit the biological activity of LPS when it is embedded in bacterial membranes (Fig. 5, C–E). Thus, polymyxin B experiments are only interpretable when particles with purified LPS are examined rather than particles with adherent bacterial debris.

FIGURE 4.

Polymyxin B (PMB) inhibits responses to titanium particles with adherent LPS (A, solid symbols) and responses to soluble LPS (B, solid symbols). A, TNFα secretion was measured in cultures of RAW264.7 cells stimulated with titanium particles with adherent LPS. The results (means ± S.E. of three experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα secretion induced in the absence of PMB. The asterisks denote p < 0.001 compared with groups without PMB. B, TNFα secretion was measured in cultures of RAW264.7 cells stimulated with soluble LPS (E. coli K12, 100 ng/ml; Invitrogen). The results (means ± S.E. of three experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα secretion induced in the absence of PMB. The open symbols depict controls in the absence of titanium particles. The asterisks denote p < 0.001 compared with groups without asterisks. Ti, titanium; adh, adherent.

FIGURE 5.

PMB does not inhibit responses to titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris (A and B) or to heat killed E. coli (C–E). TNFα protein secretion was measured following incubation in the presence or absence of PMB of RAW264.7 cells with titanium particles with adherent bacteria (A and B), heat-killed E. coli K12 (Invitrogen) (C and D), or heat-killed E. coli 0111:B4 (InVivogen) (E). The results (means ± S.E. of three or four experiments) are presented as percentages of TNFα secretion induced in the absence of PMB. In A, the solid symbols depict groups stimulated with titanium particles, and the open symbols depict controls without stimulation. In B, D, and E, the solid symbols depict groups incubated in the presence of PMB, and the open symbols depict controls without PMB. In C, the solid symbols depict groups stimulated with E. coli, and the open symbols depict controls without stimulation. None of the groups with PMB are statistically different from the matched group without PMB. Ti, titanium; adh, adherent.

DISCUSSION

The primary conclusions of this study are that 1) PAMPs adhere to the titanium particles, 2) adherent PAMPs increase the biological activity of the particles, and 3) the PAMPs do this by activating their cognate TLRs. These conclusions are consistent with the hypothesis that PAMPs produced by subclinical levels of bacteria contribute to particle-induced osteolysis in aseptic loosening of orthopaedic implants (6–10). Limitations of this study include that we only examined two PAMPs (LPS and LTA) and two TLRs (TLR2 and TLR4). Further studies will therefore be needed to determine whether other PAMPs and other TLRs can also contribute to the biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles. Future studies would also be needed to assess the potential role of other PAMP-binding receptors, such as Nod1 and Nod2 (43).

Deficiency of either TL2 or TLR4 significantly reduced the biological activity of titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris both in vitro and in vivo. The dependence on TLR4 is consistent with our previous demonstration that the bacterial debris adherent to these particles contains high levels of LPS from Gram-negative bacteria (27). The dependence on TLR2 could be caused by debris from either Gram-negative or Gram-positive bacteria (44). Additional evidence that the biological activity of the particles with adherent bacterial debris is dependent on both TLR2 and TLR4 is provided by the finding that these particles had no detectable effect on macrophages lacking both TLR2 and TLR4, which was similar to the lack of effect of the endotoxin-free particles on wild type macrophages. Similarly, the particles with adherent bacterial debris had in vivo effects on mice lacking both TLR2 and TLR4 that were equivalent to the effects of endotoxin-free particles on wild type mice.

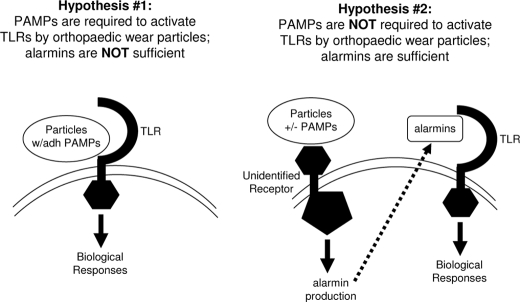

Our results support the hypothesis that TLRs are activated by wear particles with adherent PAMPs during aseptic loosening of orthopaedic implants (Hypothesis #1 depicted in Fig. 6). However, in addition to recognizing PAMPs, TLRs also act as receptors for a variety of endogenous molecules known as alarmins or endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns (45, 46). One of the best studied alarmins is heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60). It has been reported that orthopaedic wear particles induce monocytes to release Hsp60 (17), and the authors of that study proposed that the released Hsp60 may be responsible for activation of TLRs during aseptic loosening and that PAMPs are not required (Hypothesis #2 in Fig. 6). When assessing that hypothesis, it is important to take into account that at least some of the effects of many alarmins, including Hsp60, on TLR activation are due either to contamination of the preparations with bacterial PAMPs or to interactions between alarmins and PAMPs (47–52). Nonetheless, whether PAMPs or alarmins are primarily responsible for TLR activation in aseptic loosening remains controversial (17, 19). Three lines of evidence from our study argue strongly against the second hypothesis. First, if alarmins produced in response to the particles are sufficient to activate the TLRs and PAMPs are not required, then TLRs should contribute to the activity of endotoxin-free particles. However, we found that osteolysis is induced equivalently by endotoxin-free particles in wild type mice and in mice lacking TLR2 and/or TLR4 (gray bars in Fig. 1A). Thus, alarmins are not sufficient to activate these TLRs in the murine calvarial model system. Similar experiments were not possible in cell culture because the endotoxin-free particles do not induce significant responses by the bone marrow macrophages (Figs. 2 and 3, A and B) (16, 38). Second, if alarmins produced in response to the particles are sufficient to activate the TLRs and PAMPS are not required, then noncognate TLRs should contribute to the activity of particles with adherent PAMPs. However, we found that particles with adherent LTA, the TLR2 ligand, induce similar responses by wild type macrophages and macrophages lacking TLR4 (red and green bars in Fig. 2B). Similarly, particles with adherent LPS, the TLR4 ligand, induce similar responses by wild type macrophages and macrophages lacking TLR2 (red and blue bars in Fig. 3A). Thus, alarmins produced in response to the particles are not sufficient to activate either TLR2 or TLR4 in these cell cultures. Third, if alarmins produced in response to the particles are sufficient to activate the TLRs and PAMPs are not required, then polymyxin B, which binds and inactivates LPS (39–41), should not affect the biological activity of particles with adherent LPS. However, we found that polymyxin B blocks the biological activity of particles with adherent LPS (Fig. 4A). Thus, all three lines of evidence argue against the hypothesis that alarmins are sufficient for TLR activation during aseptic loosening (Hypothesis #2 in Fig. 6) and instead support the hypothesis that PAMPs are required for TLR activation during aseptic loosening (Hypothesis #1 in Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Summary of hypotheses depicting TLR activation by orthopaedic wear particles. See text for details.

Although our results argue against the hypothesis that alarmins are sufficient to activate TLRs during aseptic loosening (Hypothesis #2 in Fig. 6), they do not exclude the possibility that alarmins might act together with the PAMPs and TLRs during aseptic loosening or that alarmins might contribute to the osteolysis induced by the endotoxin-free particles that was independent of TLR activation or to the residual osteolysis that occurred in the TLR-deficient mice in response to the particles with adherent bacterial debris (Fig. 1A). One potential mechanism is that alarmins might directly stimulate post-translational processing of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 by the inflammasome (53). However, it has been demonstrated recently that phagocytosis of a wide variety of types of particles directly activates inflammasome processing by causing disruption of phagosomal membranes (21, 53–57). In those studies, priming with soluble PAMPs was required to induce transcription and translation and thereby generate the pro-cytokines to be processed by the inflammasome. A possible exception to this paradigm is that endotoxin-free monosodium urate crystals have been reported to directly stimulate TLR2 and TLR4 (58). However, other workers have reported conflicting data (59), and a third group has reported intermediate results (60). Irrespective of whether monosodium urate crystals directly activate TLRs, orthopaedic wear particles with adherent PAMPs may be able to perform both functions by stimulating TLR signaling to induce transcription and translation and by activating inflammasome processing. Indeed, one of the studies of phagosomal disruption showed that LPS incorporation into the surface of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) particles substantially increased stimulation of IL-1β secretion (55). Although inflammasome processing was not examined in the current study, we have previously shown that secretion of mature IL-1β is substantially increased by adherence of PAMPs to orthopaedic wear particles and that this depends on TLR activation (16), and other investigators have shown that stimulation of IL-1β secretion by orthopaedic wear particles depends on inflammasome processing (61, 62). An interesting variation on this model is reflected in the recent demonstration that TLR2 is activated by alkane polymers released into peri-prosthetic tissue by particles of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene, whereas the ultra high molecular weight polyethylene particles themselves disrupt phagosomal membranes and thereby activate inflammasome processing (21, 63). Because ultra high molecular weight polyethylene particles are the predominant type of particles in most aseptic loosening patients (64), the released alkane polymers may act together with bacterially derived PAMPs to activate TLRs in these patients.

Our results also demonstrate that the LPS accumulation induced by implantation of endotoxin-free particles (14, 15) is not required for the osteolysis that occurs within 7 days in murine calvaria because it is not reduced in mice that lack TLRs (gray bars in Fig. 1A). Nonetheless, LPS accumulation may contribute to osteolysis that occurs over a longer time frame, for example in other animal models or in patients with aseptic loosening.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that TLR activation by PAMPs such as LPS and LTA contributes to inflammatory responses induced by orthopaedic wear particles in cell culture and murine models of aseptic loosening of orthopaedic implants. Future studies are needed to determine the relative importance of PAMPs and TLR activation in patients with aseptic loosening.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lindsay Bonsignore for designing the figures. We are grateful to S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) for the gift of TLR2- and TLR4-deficient mice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant T32 AR07505 (to M. A. B.). This work was also supported by a grant from the Sulzer Medical Research Trust Fund (to E. M. G. and V. M. G.).

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of John B. Morrill, Ph.D.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- PAMP

- pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- LTA

- lipoteichoic acid

- PMB

- polymyxin B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lorenzo J., Horowitz M., Choi Y. (2008) Endocr. Rev. 29, 403–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanssen A. D., Spangehl M. J. (2004) Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 420, 63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt G., Murnaghan C., Reilly J., Meek R. M. (2007) Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 460, 240–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenfield E. (2006) in Encyclopedia of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering (Wnek G., Bowlin G. eds) pp. 1–8, Taylor Francis, New York [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenfield E. M., Bi Y., Ragab A. A., Goldberg V. M., Van De Motter R. R. (2002) J. Orthop. Res. 20, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfield E. M., Bi Y., Ragab A. A., Goldberg V. M., Nalepka J. L., Seabold J. M. (2005) J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 72, 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson C. L., McLaren A. C., McLaren S. G., Johnson J. W., Smeltzer M. S. (2005) Clin. Orthop. 437, 25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundfeldt M., Carlsson L. V., Johansson C. B., Thomsen P., Gretzer C. (2006) Acta. Orthop. 77, 177–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neut D., van der Mei H., Bulstra S., Busscher H. (2007) Acta Orthop. 78, 299–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenfield E., Bechtold J.Implant Wear Symposium 2007 Biologic Working Group, (2008) J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surgeons 16, (suppl.) S56–S62 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoenders C. S., Harmsen M. C., van Luyn M. J. (2008) J. Biomed. Mater Res. B Appl. Biomater. 86, 291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engesaeter L. B., Lie S. A., Espehaug B., Furnes O., Vollset S. E., Havelin L. I. (2003) Acta Orthop. Scand. 74, 644–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nalepka J. L., Lee M. J., Kraay M. J., Marcus R. E., Goldberg V. M., Chen X., Greenfield E. M. (2006) Clin. Orthop. 451, 229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing Z., Pabst M. J., Hasty K. A., Smith R. A. (2006) J. Orthop. Res. 24, 959–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatro J. M., Taki N., Islam A. S., Goldberg V. M., Rimnac C. M., Doerschuk C. M., Stewart M. C., Greenfield E. M. (2007) J. Orthop. Res. 25, 361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bi Y., Seabold J. M., Kaar S. G., Ragab A. A., Goldberg V. M., Anderson J. M., Greenfield E. M. (2001) J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 2082–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao H. N., Zheng B., Nasser S., Ren W., Latteier M., Wooley P., Morawa L. (2010) J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 92, 1373–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takagi M., Tamaki Y., Hasegawa H., Takakubo Y., Konttinen L., Tiainen V., Lappalainen R., Konttinen Y., Salo J. (2007) J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 81, 1017–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lähdeoja T., Pajarinen J., Kouri V. P., Sillat T., Salo J., Konttinen Y. T. (2010) J. Orthop. Res. 28, 184–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamaki Y., Takakubo Y., Goto K., Hirayama T., Sasaki K., Konttinen Y. T., Goodman S. B., Takagi M. (2009) J. Rheumatol. 36, 598–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maitra R., Clement C. C., Scharf B., Crisi G. M., Chitta S., Paget D., Purdue P. E., Cobelli N., Santambrogio L. (2009) Mol. Immunol. 47, 175–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tunney M. M., Patrick S., Curran M. D., Ramage G., Hanna D., Nixon J. R., Gorman S. P., Davis R. I., Anderson N. (1999) J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 3281–3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neut D., van Horn J. R., van Kooten T. G., van der Mei H. C., Busscher H. J. (2003) Clin. Orthop. 413, 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dempsey K. E., Riggio M. P., Lennon A., Hannah V. E., Ramage G., Allan D., Bagg J. (2007) Arthritis Res. Ther. 9, R46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trampuz A., Piper K. E., Jacobson M. J., Hanssen A. D., Unni K. K., Osmon D. R., Mandrekar J. N., Cockerill F. R., Steckelberg J. M., Greenleaf J. F., Patel R. (2007) N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 654–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deininger S., Traub S., Aichele D., Rupp T., Baris T., Möller H. M., Hartung T., von Aulock S. (2008) Immunobiology 213, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ragab A. A., Van De Motter R., Lavish S. A., Goldberg V. M., Ninomiya J. T., Carlin C. R., Greenfield E. M. (1999) J. Orthop. Res. 17, 803–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashwood P., Thompson R. P., Powell J. J. (2007) Exp. Biol. Med. 232, 107–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nalepka J. L., Greenfield E. M. (2004) BioTechniques 37, 413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeuchi O., Hoshino K., Kawai T., Sanjo H., Takada H., Ogawa T., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) Immunity 11, 443–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Sanjo H., Ogawa T., Takeda Y., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 3749–3752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillette-Ferguson I., Daehnel K., Hise A. G., Sun Y., Carlson E., Diaconu E., McGarry H. F., Taylor M. J., Pearlman E. (2007) Infect. Immun. 75, 5908–5915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hise A. G., Daehnel K., Gillette-Ferguson I., Cho E., McGarry H. F., Taylor M. J., Golenbock D. T., Fitzgerald K. A., Kazura J. W., Pearlman E. (2007) J. Immunol. 178, 1068–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaar S. G., Ragab A. A., Kaye S. J., Kilic B. A., Jinno T., Goldberg V. M., Bi Y., Stewart M. C., Carter J. R., Greenfield E. M. (2001) J. Orthop. Res. 19, 171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beidelschies M. A., Huang H., McMullen M. R., Smith M. V., Islam A. S., Goldberg V. M., Chen X., Nagy L. E., Greenfield E. M. (2008) J. Cell. Physiol. 217, 652–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai J. C., He P., Chen X., Greenfield E. M. (2006) Bone 38, 509–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taki N., Tatro J. M., Nalepka J. L., Togawa D., Goldberg V. M., Rimnac C. M., Greenfield E. M. (2005) J. Orthop. Res. 23, 376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bi Y., Collier T. O., Goldberg V. M., Anderson J. M., Greenfield E. M. (2002) J. Orthop. Res. 20, 696–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morrison D. C., Jacobs D. M. (1976) Immunochemistry 13, 813–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duff G., Atkins E. (1982) J. Immunol. Methods 52, 333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao J. J., Xue Q., Zuvanich E. G., Haghi K. R., Morrison D. C. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 751–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearl J., Huang Z., Ma T., Smith R., Goodman S. (2008) Trans. Orthop. Res. Soc. 33, 1936 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inohara N., Chamaillard M., McDonald C., Nuñez G. (2005) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 355–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. (2003) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matzinger P. (2007) Nat. Immunol. 8, 11–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bianchi M. E. (2007) J. Leukocyte Biol. 81, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warger T., Hilf N., Rechtsteiner G., Haselmayer P., Carrick D. M., Jonuleit H., von Landenberg P., Rammensee H. G., Nicchitta C. V., Radsak M. P., Schild H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22545–22553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian J., Avalos A. M., Mao S. Y., Chen B., Senthil K., Wu H., Parroche P., Drabic S., Golenbock D., Sirois C., Hua J., An L. L., Audoly L., La Rosa G., Bierhaus A., Naworth P., Marshak-Rothstein A., Crow M. K., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Kiener P. A., Coyle A. J. (2007) Nat. Immunol. 8, 487–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Youn J. H., Oh Y. J., Kim E. S., Choi J. E., Shin J. S. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 5067–5074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osterloh A., Kalinke U., Weiss S., Fleischer B., Breloer M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4669–4680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsan M. F., Gao B. (2009) J. Leukocyte Biol. 85, 905–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lyle D. B., Breger J. C., Baeva L. F., Shallcross J. C., Durfor C. N., Wang N. S., Langone J. J. (2010) J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 94, 893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bryant C., Fitzgerald K. A. (2009) Trends Cell Biol. 19, 455–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hornung V., Bauernfeind F., Halle A., Samstad E. O., Kono H., Rock K. L., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 847–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Demento S. L., Eisenbarth S. C., Foellmer H. G., Platt C., Caplan M. J., Mark Saltzman W., Mellman I., Ledizet M., Fikrig E., Flavell R. A., Fahmy T. M. (2009) Vaccine 27, 3013–3021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharp F. A., Ruane D., Claass B., Creagh E., Harris J., Malyala P., Singh M., O'Hagan D. T., Pétrilli V., Tschopp J., O'Neill L. A., Lavelle E. C. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 870–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halle A., Hornung V., Petzold G. C., Stewart C. R., Monks B. G., Reinheckel T., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Moore K. J., Golenbock D. T. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 857–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu-Bryan R., Scott P., Sydlaske A., Rose D. M., Terkeltaub R. (2005) Arthritis Rheum. 52, 2936–2946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen C. J., Shi Y., Hearn A., Fitzgerald K., Golenbock D., Reed G., Akira S., Rock K. L. (2006) J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2262–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gasse P., Riteau N., Charron S., Girre S., Fick L., Pétrilli V., Tschopp J., Lagente V., Quesniaux V. F., Ryffel B., Couillin I. (2009) Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 179, 903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caicedo M. S., Desai R., McAllister K., Reddy A., Jacobs J. J., Hallab N. J. (2009) J. Orthop. Res. 27, 847–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.St. Pierre C. A., Chan M., Iwakura Y., Ayers D. C., Kurt-Jones E. A., Finberg R. W. (2010) J. Orthop. Res., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maitra R., Clement C. C., Crisi G. M., Cobelli N., Santambrogio L. (2008) PloS. One 3, e2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marshall A., Ries M. D., Paprosky W. (2008) J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surgeons 16, (Suppl. 1) S1–S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.