Abstract

Prenatal alcohol exposure can lead to a range of physical, neurological, and behavioral alterations referred to as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Variability in outcome observed among children with FASD is likely related to various pre- and postnatal factors, including nutritional variables. Choline is an essential nutrient that influences brain and behavioral development. Recent animal research indicates that prenatal choline supplementation leads to long-lasting cognitive enhancement, as well as changes in brain morphology, electrophysiology and neurochemistry. The present study examined whether choline supplementation during ethanol exposure effectively reduces fetal alcohol effects. Pregnant dams were exposed to 6.0 g/kg/day ethanol via intubation from gestational day (GD) 5-20; pair-fed and lab chow controls were included. During treatment, subjects from each group received choline chloride (250 mg/kg/day) or vehicle. Physical development and behavioral development (righting reflex, geotactic reflex, cliff avoidance, reflex suspension and hindlimb coordination) were examined. Subjects prenatally exposed to alcohol exhibited reduced birth weight and brain weight, delays in eye opening and incisor emergence, and alterations in the development of all behaviors. Choline supplementation significantly attenuated ethanol’s effects on birth and brain weight, incisor emergence, and most behavioral measures. In fact, behavioral performance of ethanol-exposed subjects treated with choline did not differ from that of controls. Importantly, choline supplementation did not influence peak blood alcohol level or metabolism, indicating that choline’s effects were not due to differential alcohol exposure. These data indicate early dietary supplements may reduce the severity of some fetal alcohol effects, findings with important implications for children of women who drink alcohol during pregnancy.

Keywords: fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, ethanol, physical development, reflex development, treatment

1. Introduction

The consequences of prenatal alcohol exposure range from physical anomalies and growth retardation [35] to CNS dysfunction and behavioral alterations [59,67]. In the U.S., it is estimated that around 0.5–3.1 per 1000 births [13,45] suffer from a full blown fetal alcohol syndrome and an estimated 1 in 100 live births exhibit at least some adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure [68]. It is clear that fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), the term used to describe the range of fetal alcohol effects, constitute a serious problem throughout the world [86].

Given that women continue to drink alcohol during pregnancy, it is important to identify methods to reduce the severity of FASD. Both clinical and animal studies suggest that postnatal behavioral and environmental factors can mitigate some of ethanol’s adverse effects, and may improve outcome following prenatal alcohol exposure [28,38,40,72]. We have reported that choline supplementation during early postnatal development can also reduce the severity of some behavioral alterations associated with developmental alcohol exposure. Specifically, choline supplementation from postnatal days (PD) 2-21 reduced the severity of working memory deficits in adult rats induced by prenatal alcohol exposure [78]. Choline supplementation from PD 4-30 also significantly reduced the severity of spatial learning deficits [77], overactivity [77], trace eyeblink conditioning [81] and trace fear conditioning deficits [84], but not motor coordination deficits [79], associated with alcohol exposure during the 3rd trimester equivalent brain growth spurt (PD 4-9 in the rat is commonly accepted as a model of the 3rd trimester equivalent [17], although there is some variability among models used to compare development between rats and humans (see www.translatingtime.net)). More recently, we reported that choline supplementation from PD 10-30, during a period equivalent to postnatal development in humans, reduces the severity of learning deficits and hyperactivity associated with 3rd trimester alcohol exposure [74]. Collectively, these data suggest that choline supplementation during late gestation and/or the early postnatal period may effectively attenuate ethanol’s adverse effects on behavioral development.

Ideally, one would intervene at the time of alcohol exposure, preventing or reducing the amount of alcohol-related CNS damage. A number of potential therapeutics have been identified, primarily based on putative mechanisms of alcohol-induced teratogenesis, including neurotrophic agents [9,18,30,31,46], neuroactive peptides [10,82,91,92,99], antioxidants [11,14,29,44,55] and NMDA receptor antagonists [75,76]. The present study examines whether choline supplementation would be effective when administered during prenatal alcohol exposure. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the effects of choline supplementation coincident with prenatal alcohol exposure.

Choline is recognized as an essential nutrient by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences [8] and is necessary for fetal development [95]. In fact, choline deficiency is associated with increased neural tube defects and CNS dysfunction [3,16,19,20,48,51,71]. A growing literature indicates that prenatal choline supplementation in typically developing (non alcohol-exposed) rats leads to long-lasting enhancements in cognitive functioning, as well as changes in CNS structure and function [47,50]. Given that choline serves not only as a precursor to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, but also as a precursor to cell membrane constituents phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, and can act as a methyl donor and epigenetic factor, its effects may be quite broad. In the present study, we examined whether prenatal choline supplementation, during the ethanol exposure period, would affect a range of physical and behavioral outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

All procedures included in this study were approved by the SDSU IACUC and are in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.1 Treatment

Subjects were derived from timed births at the Center for Behavioral Teratology, San Diego State University Animal Care facilities. A Sprague-Dawley male and female were housed together overnight and the presence of a seminal plug in the morning indicated mating and designated gestational day (GD) 0. Pregnant females were then randomly assigned to one of six treatment groups in a 3 (ethanol-exposed (EtOH), yoked pair-fed (PF), or ad lib control (LC)) × 2 (choline supplementation, control) design. Each group included 10–14 dams (n’s are shown in Table I). Subjects were singly housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with access to food (LabDiet® 5001, Richmond, IN, which contains 2.25 g choline chloride/kg diet) and water. On GD 5-20, all dams were orally gavaged once a day. Ethanol-exposed dams received 6.0 g/kg/day in a 28.5% (v/v) ethanol solution (0.02675 ml/g of body weight), whereas PF dams received isocaloric maltose dextrin, and LC dams received vehicle (saline). Daily food intake was measured for EtOH dams; each pair-fed dam was matched to an EtOH dam of similar weight and food intake was yoked. Choline chloride (250 mg/kg/day) [12,93] or saline control was added to the intubation formula. Dams were weighed daily.

Table I.

Peak BAC, and Delivery Statistics: Percent of maternal body weight gained during pregnancy, length of gestation, male/female ratio, and number of litters for each prenatal treatment group

| Prenatal treatment | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC | PF | EtOH | |||||||||||

| Vehicle (n=12) | Choline (n=13) | Vehicle (n=14) | Choline (n=10) | Vehicle (n=11) | Choline (n=12) | ||||||||

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | ||

| BAC | † GD 5 | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | 191 | 26 | 221 | 19 | ||||

| † GD 20 | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | 258 | 26 | 239 | 12 | |||||

| Maternal % Body Weight Gain | * 49.6 | 2.9 | 52.8 | 2.3 | 33.9 | 1.8 | 36.5 | 1.1 | 36.7 | 3.0 | 34.7 | 2.7 | |

| Litter Size | 13.7 | 0.9 | 13.7 | 0.9 | 14.3 | 0.6 | 14.4 | 0.6 | 14.5 | 0.9 | 12.8 | 0.9 | |

| Gestational Length (days) | 21.5 | 0.1 | 21.4 | 0.1 | 21.4 | 0.2 | 21.5 | 0.2 | 21.5 | 0.2 | 21.8 | 0.2 | |

| Male Ratio | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.03 | |

Symbols:

LC significantly different from PF and EtOH, collapsed over choline treatment (p<.05)

Additional pregnant rats: EtOH-Vehicle (n=6); EtOH-Choline (n=5)

Notes: EtOH= Ethanol; PF= Pair-Fed; LC= Lab Chow; n= number of litters, SEM= Standard Error of the Mean, BAC= Blood Alcohol Concentration, GD= Gestational day

Beginning on GD 20, dams were monitored each morning for birth of pups. The day of birth (usually GD 22) was recorded as PD 0 and dams were not disturbed that day. On PD 1, litters were pseudorandomly culled to 10 pups (5 males and 5 females, if possible). Brain tissue from one extra male and one extra female pup were collected on PD 1 when possible (depending on number of pups born and male/female ratio from each litter).

2.2 Blood Alcohol Level

Blood alcohol levels were measured in a separate group of adult pregnant rats, to determine if choline supplementation influenced blood alcohol level. Subjects were treated with 6.0 g/kg ethanol with or without 250 mg/kg choline supplementation. Forty microliters of blood were drawn from a tail clip from each subject at 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 8.0 and 24 hours after the alcohol gavage on GD 5 and 20. Blood samples were analyzed using the Analox Alcohol Analyzer (Model AM1, Analox Instruments; Lunenburg, MA).

2.3 Physical development

On PD 1-21, physical signs of development were monitored and recorded daily for all pups. The physical signs included body weight, onset of eye opening, ear unfurling and tooth eruption. Body weight was recorded in grams (g). Eye opening was defined as a full slit length break in the membrane covering the eyes. Ear unfurling was defined as unfolding of external pinnae of both ears to the fully erect position and tooth eruption was recorded at the first break in gum for both upper incisors and lower incisors [22,39].

2.4 Behavioral testing

To reduce the possibility of carryover effects and excessive handling [21], different sex pairs within each litter were tested on the various behavioral tasks. One sex pair was tested on the reflex battery and was sacrificed on PD 21. The other sex pairs underwent testing on other behavioral tasks (motor coordination and balance, open field activity, spatial learning, working memory), which will be presented in a separate report.

2.5 Reflex development

On PD 2-18, one sex pair per litter was tested on a series of reflex development tasks to examine sensorimotor maturation [22]: righting reflex, geotactic reflex, cliff avoidance, grip strength and hindlimb coordination. Righting reflex was evaluated on PD 2-7. On a warm heating pad, each pup was placed in the supine position and the latency to right, defined by the four paws touching the floor, was recorded. A maximum of 30 seconds was provided for task completion; pups were tested for two trials per day. Maturation of this response was reached when the pup successfully righted itself in less than five seconds during both trials.

Subjects were tested for geotactic reflexes on PD 7-15. During this task, each pup was placed facing downward on a rough board held at a 45° slant. Latency to rotate 180 degrees was measured with a maximum of 3 minutes given per trial, with two trials per day. Success was considered when the pup performed a 180-degree turn within the allotted time.

Cliff avoidance was evaluated on PD 6-12, with two trials per day. Each rat pup was placed with its head and front paws over a ledge. The latency to retract the body 1.5 cm from the edge was recorded. Subjects were given a maximum of 30 sec per trial.

Finally, on PD 12-20, grip strength and hindlimb coordination were measured. Each pup was suspended by its forefeet from a wire, 2-mm in diameter. A cage filled with bedding was placed under the wire should the pup fall. Subjects were given a maximum of 30 seconds per trial, for 2 trials per day. A successful grasp trial was recorded if the rat pup was able to hold on to the wire for 30 sec. A successful coordination trial was recorded if the pup was able to place one of its hindlimbs on the wire.

Developmental evaluations were sequentially performed on the same sex pair from each litter. Subjects were first evaluated in the earlier reflexes and each new test was added at the end of the sequence. The intertrial interval between the two trials in each test was 5–10 sec. Time between reflex tests varied from 5–30 mins, depending on the number of subjects evaluated on a particular day (5–30 min).

2.6 Data Analyses

Data were analyzed with ANOVAs, using SPSS software. Prenatal treatment (Ethanol, Pair-fed, Lab Chow), choline (choline, vehicle), and sex served as between-subject factors on all measures. Dependent variables recorded across time were analyzed with repeated measures. Because within-litter variability is different from between-litter variability [34], for body weight and physical development data, the mean from each litter was determined and used as one data point. In addition, these data were also analyzed using litter as a nested factor. Body weight data were analyzed with day as a repeated measure. Follow-up comparisons were conducted with LSD post-hoc analyses with p <.05. For the reflex development measures where a criterion was established, the percent of subjects per group reaching criterion was calculated day by day. Fisher exact probability tests for independent samples were performed to compare percentage of subjects reaching criterion each day (p<.05).

3. Results

3.1 Gestation and birth variables

Maternal body weight during gestation was significantly affected by the prenatal ethanol treatment. No significant differences were observed in the body weight of the dams on gestational day 0 (GD 0) (p > 0.1). Analysis of the percent body weight gained during pregnancy showed that LC dams gained significantly more weight than PF and EtOH-treated dams relative to their initial body weight (data collapsed across choline treatment) [F(2, 66) = 28.61; p<.005] (Table I). Choline treatment did not significantly affect dam body growth. As seen in Table I, neither litter size nor sex ratio of pups were significantly affected by ethanol or choline treatments.

3.2 Blood Alcohol Concentrations (BAC)

Choline administration during prenatal ethanol treatment did not significantly affect the peak BAC or alcohol metabolism within the parameters of the present experiment. Data were statistically analyzed using a mixed ANOVA with choline treatment as a between subject factor and gestational day and time as repeated measures. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of Time [F(4,36) = 74.6; p<.001], as alcohol concentration reached a peak within 2–4 hours after the intubation, declined significantly after 8 hours and approached 0 24 hrs after the ethanol intubation. There were no significant main or interactive effects of gestational day, although peak blood alcohol levels tended to be higher on GD 20 (see Table I for peak blood alcohol concentrations). Importantly, there were no significant effects of choline on BAC at any time, indicating that choline did not alter ethanol metabolism.

3.3 Body Weight

All pups in the litter were weighed daily from PD 1-21 and the means for males and females within each litter were used as the unit of analyses (Table II). An overall ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of EtOH [F(2, 132) = 11.5; p<.001], as pups in the Ethanol and PF groups had significantly lower body weights than LC controls, as well as EtOH × Day [F(40, 2640) = 3.3; p<.001] and EtOH × Choline × Day [F(40, 2640) = 2.0; p<.001] interactions. There were also effects of Day [F(20, 2640)=13881; p<.001], Sex [F(1, 132)=8.0; p<.01], and a Day × Sex [F(20, 2640) = 5.4; p<.001] interaction due to faster growth among males compared to females.

Table II.

Mean and SEM for body weights during lactation.

Data collapsed across sex and presented at three-day intervals

| Postnatal Day | Prenatal treatment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC | PF | EtOH | ||||||||||

| Vehicle | Choline | Vehicle | Choline | Vehicle | Choline | |||||||

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| 1 | 7.3 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 6.7 | 0.1* | 6.9 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 0.1* | 6.9 | 0.1*** |

| 3 | 10.1 | 0.2 | 10.2 | 0.2 | 9.1 | 0.1* | 9.5 | 0.2 | 8.4 | 0.2** | 8.8 | 0.2 |

| 6 | 15.1 | 0.3 | 15.3 | 0.3 | 14.1 | 0.2* | 14.5 | 0.3 | 13.0 | 0.2** | 13.6 | 0.3 |

| 9 | 21.3 | 0.4 | 21.3 | 0.5 | 19.8 | 0.3* | 20.4 | 0.4 | 18.8 | 0.4** | 19.8 | 0.5 |

| 12 | 27.9 | 0.5 | 27.9 | 0.6 | 26.5 | 0.3* | 26.7 | 0.5 | 25.1 | 0.5** | 26.4 | 0.6 |

| 13 | 30.1 | 0.5 | 29.7 | 0.6 | 28.5 | 0.4* | 28.9 | 0.6 | 27.0 | 0.4** | 28.7 | 0.6*** |

| 15 | 34.5 | 0.5 | 33.8 | 0.6 | 32.8 | 0.4* | 33.1 | 0.7 | 31.3 | 0.5** | 32.9 | 0.7 |

| 18 | 40.9 | 0.6 | 40.2 | 0.7 | 39.2 | 0.5* | 39.0 | 0.8 | 37.3 | 0.6** | 39.0 | 0.9 |

| 21 | 52.5 | 0.8 | 52.0 | 0.9 | 50.6 | 0.8* | 50.6 | 0.8 | 47.1 | 0.9** | 49.6 | 1.1 |

significantly different from LC vehicle;

significantly different from LC and PF vehicle,

significantly different from EtOH vehicle

Follow-up analyses examined the EtOH × Choline × Day interaction. Analyses of saline-treated subjects demonstrated a significant effect of EtOH [F(2, 68) = 13.5], day [F(20,1360) = 8216, p<.001] and an EtOH × day interaction [F(40, 1360) = 5.1, p<.01]. At birth, ethanol-exposed and pair-fed controls weighed significantly less than lab chow controls. By PD 2, the ethanol-exposed subjects weighed less than pair-feds, which weighed significantly less than lab chows and this trend continued through PD 21. In contrast, there was no effect of ethanol exposure on body weights among choline-treated subjects, only an effect of day [F(20, 1280) = 5930, p<.001]. Two-way ANOVAs (Choline × Day) were also used to determine the choline effect within each ethanol treatment group. Analysis of the ethanol-exposed groups showed significant main effects of Day [F(20, 880) = 3424; p<.001], and a Day × Choline interaction [F(20, 880)= 2.18; p<.005]. The main effect of Choline approached significance [F(1, 44) = 3.23; p=.08]. Daily analyses of body weights of the pups prenatally exposed to ethanol revealed that on PD 1, EtOH pups weighed significantly less than EtOH + Choline pups [F(1, 44) = 5.9; p<.05] (Table II). On subsequent days, this tendency was maintained, although, with the exception of PD 13, the difference between these two groups did not reach statistical significance.

Similar analyses for each of the control groups failed to show any effect of choline on the body weight of the pups. As expected, a significant main effect of day was evident in both PF and LC treatment groups, revealing the pups’ growth across days (F(20, 920) = 5103; p<.001 and F(20, 960) = 5817; p<.001, respectively).

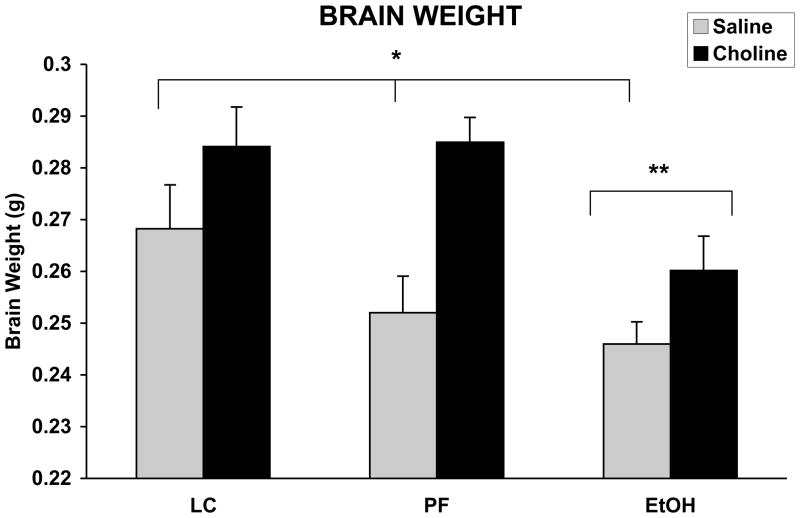

3.4 Brain Weight

Brains were collected from approximately 50–75% litters from each treatment group (EtOH n = 8/12, EtOH + Choline n = 7/13, PF n = 7/14, PF + Choline n = 6/10, LC n = 6/11, LC + Choline n = 10/12). Prenatal ethanol exposure significantly reduced brain weight, whereas choline supplementation significantly increased brain weight on PD 1 pups (see Figure 1). The ANOVA revealed significant main effects of EtOH [F(2,90) = 5.8; p< .05] and Choline [F(1,90) = 14.3; p< .05] treatments. When collapsed across choline treatment, brain weights of ethanol-exposed subjects were significantly lower than controls. Overall, brain weights of choline-treated pups were heavier than vehicle treated controls. No significant interactions were revealed in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Mean (+ SEM) brain weight on PD 1. Brains of ethanol-exposed weighed significantly less than both control groups and choline significantly increased brain weight in all groups. There was no significant interaction between ethanol and choline treatment. * = vehicle treated groups significantly different from choline treated groups, ** = EtOH significantly different from both control groups

3.5 Physical Development

The day of emergence of physical features is illustrated in Table III. Data on eye opening from 2 litters (one PF and one EtOH + C) were not collected due to experiment error. Prenatal alcohol exposure significantly delayed the eye opening of the pups compared to both control groups. The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of EtOH [F(2,128) = 17.8; p<.001], but no Choline effect was observed. Similarly, prenatal ethanol delayed the emergence of incisors.

Table III.

Physical Development. Days of age for the appearance of the following physical features: ears unfolded, upper and lower incisors cutting the gums and eyes opening

| Physical Feature | Prenatal treatment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC | PF | EtOH | ||||||||||

| Vehicle | Choline | Vehicle | Choline | Vehicle | Choline | |||||||

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| Ears Unfolded | 3.1 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Lower Incisors | *** 10.3 | 0.4 | 9.6 | 0.4 | 9.8 | 0.3 | 9.8 | 0.3 | **11.1 | 0.3 | 10.2 | 0.3 |

| Upper Incisors | *** 10.6 | 0.2 | 10.1 | 0.2 | 10.6 | 0.2 | 10.4 | 0.2 | **11.6 | 0.3 | 11.2 | 0.2 |

| Eyes Opened | 14.1 | 0.2 | 14.1 | 0.2 | 14.2 | 0.2 | 14.4 | 0.1 | **14.9 | 0.2 | 14.9 | 0.2 |

EtOH significantly different from both control groups,

choline treatment significantly different from vehicle

The ANOVA revealed that the lower incisors emerged significantly earlier than upper incisors for all pups [F(1,132) = 31.6; p<.001]. There were also significant main effects of EtOH [F(2,132) = 18.9; p<.001] and Choline [F(1,132) = 10.4; p<.05] on incisor emergence. Follow-up analyses illustrated that both upper and lower incisors emerged significantly later in pups prenatally exposed to alcohol, compared to both control groups. In contrast, incisors emergence was observed earlier in subjects that received prenatal choline supplementation. Finally, ear unfolding was not significantly affected by either prenatal EtOH or Choline treatments. There were no main or interactive effects of sex on any measures. Similar results were obtained when analyzing the data with litter as a nested factor on all dependent variables.

3.6 Reflex Ontogeny

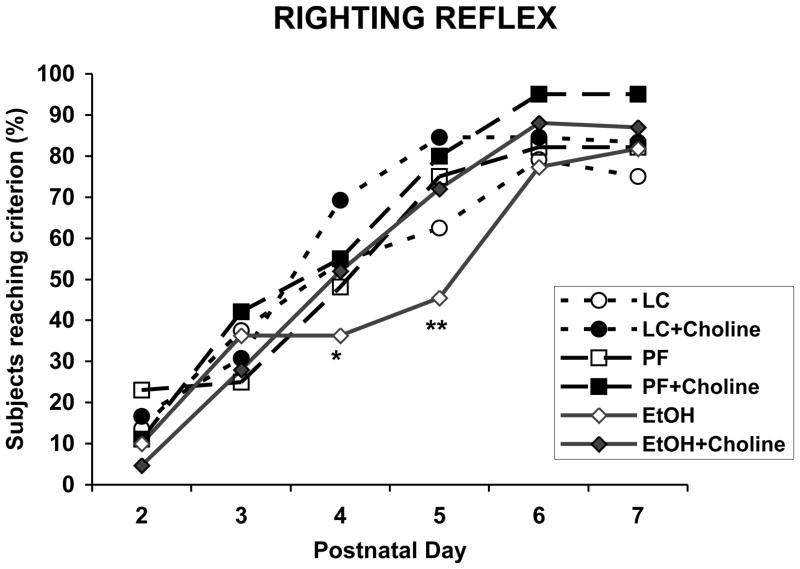

3.6.1 Surface righting reflex

Prenatal ethanol exposure significantly delayed the age of maturation of the surface righting reflex (Figure 2), an effect that was mitigated with choline supplementation. On PD 4, the percent of EtOH + Vehicle subjects showing a mature surface righting reflex (able to right themselves within 5 sec for 2 trials) began to lag and was significantly lower than that of the LC + Choline group. By PD 5, the percent of EtOH + Vehicle subjects was significantly lower than all other groups, including the EtOH + Choline group, with the exception of the LC group [Fisher’s p’s<.05]. In fact, EtOH + Choline subjects showed a maturation rate similar to and not significantly different from that observed in control groups. There were no longer significant differences among groups by PD 6.

Figure 2.

Percent of subjects who exhibited a mature surface righting reflex across PD 2-7. Fewer EtOH + Vehicle subjects showed a mature response compared to the LC + Choline subjects on PD 4 and compared to all other groups except the LC + Vehicle group on PD 5. * = significantly different from LC + Choline; ** = significantly different from all other groups except LC + Vehicle group

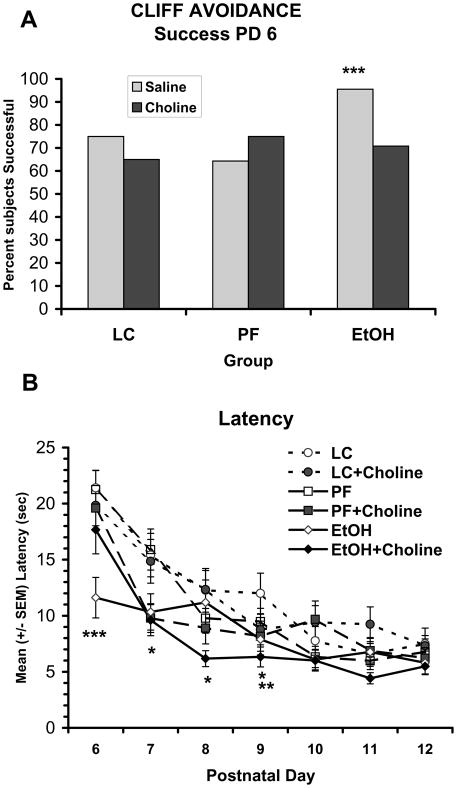

3.6.2 Cliff avoidance

Prenatal ethanol exposure significantly affected the latency to retract from the edge at the beginning of testing. On PD 6, ethanol-exposed subjects treated with vehicle were more successful in retracting compared to other groups [Fisher’s p’s <.05] (Figure 3A). In addition, prenatally alcohol-exposed subjects treated with vehicle exhibited shorter latencies than all other groups, whereas prenatally alcohol-exposed subjects that received choline supplementation performed similar to control subjects (Figure 3B). An overall ANOVA on latency to retract revealed significant main effects of EtOH [F(2, 132) = 7.7; p<.001], Day [F(6, 792) = 59.4; p<.001], and the interactions EtOH × Choline × Day [F(12, 792) = 1.9; p<.01] and Choline × Day [F(6, 792) = 2.9; p<.01]. Follow-up analyses were conducted for each testing day to further investigate these interactions. On PD 6, performance of the EtOH + Vehicle group was significantly different from all other groups, producing an EtOH × Choline [F(2,138) = 2.9, p<.05] interaction and main effect of EtOH [F(2,138) = 3.9, p<.05]. Follow-up analyses confirmed that ethanol-exposed subjects treated with vehicle were faster than those treated with choline [F(1,44) = 8.0; p<.01]), whereas ethanol-exposed subjects treated with choline did not differ from controls. There were also main effects of ethanol treatment on PD 7 [F(2,138) = 3.2; p<.05], PD 8 [F(2,138) = 3.0; p=.05], and PD 9 [F(2,138) = 3.7, p<.05], as subjects prenatally exposed to ethanol responded faster than LC controls. Additionally, choline-treated animals showed significantly shorter latencies than vehicle-treated subjects on PD 9 [main effect of choline; F(1, 138) = 6.1, p<.05].

Figure 3.

Percent of subjects successful on PD 6 (A) and mean (+/− SEM) latency to retract from the cliff over testing days (B). On PD 6, subjects exposed to prenatal alcohol and treated with vehicle were more successful and had significantly shorter latencies compared to all other groups. On subsequent days (PD 7-9), ethanol-exposed subjects were faster than LC controls and on PD 9, choline-treated subjects were faster than vehicle-treated subjects (Panel B). *** = EtOH + Vehicle significantly different from all other groups, * = EtOH significantly different from LC, ** = choline significantly different from vehicle

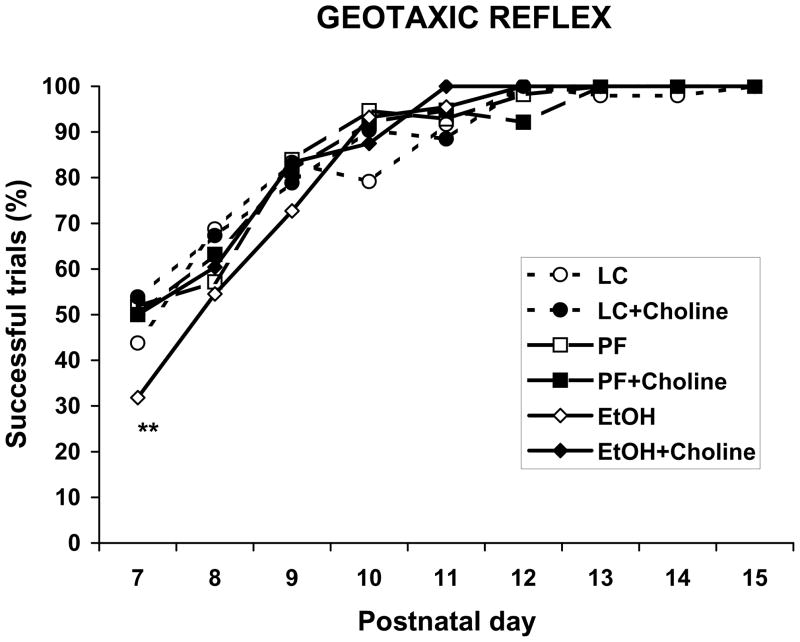

3.6.3 Negative Geotaxis

Prenatal ethanol exposure significantly affected the number of subjects that exhibited the negative geotaxic reflex on PD 7. The percent of EtOH + Vehicle subjects showing successful responses on PD 7 was significantly lower than the percentage of subjects in the EtOH + Choline group as well as all control groups (Fisher p’s <.05) with the exception of the LC + Vehicle group (see Figure 4). No significant differences were observed during the following days of testing.

Figure 4.

Percentage of successful responses on the geotaxic reflex task over testing days. On PD 7, ethanol-exposed subjects treated with vehicle were less successful compared to all groups except the LC + vehicle group.

** = significantly different from all groups except LC + vehicle

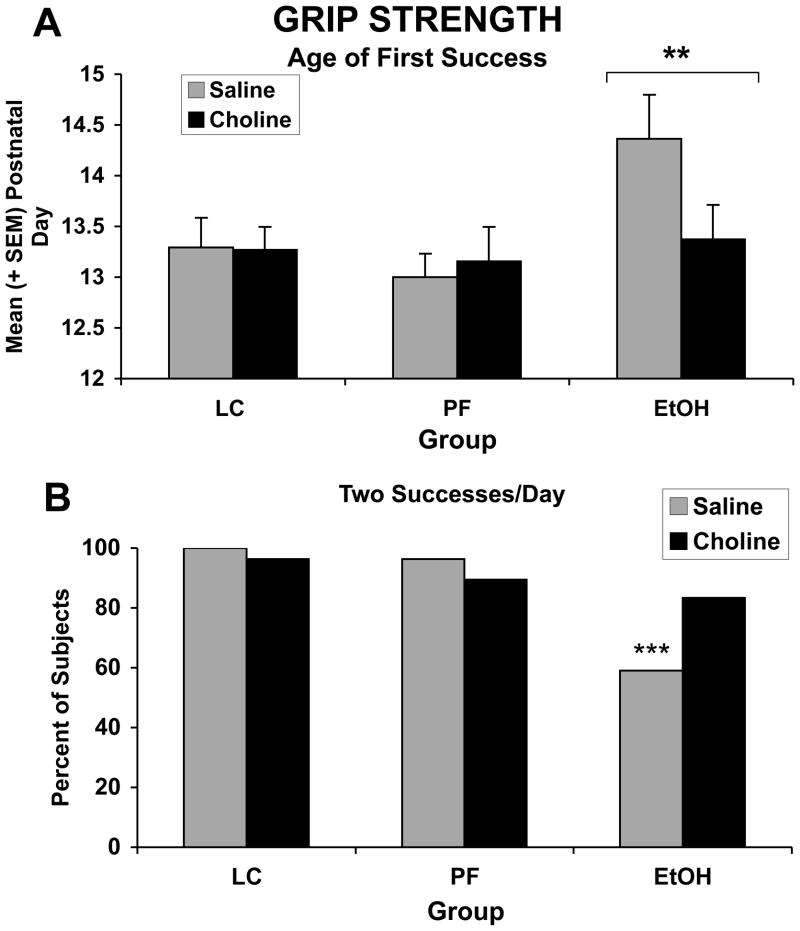

3.6.4 Grip Strength

The ANOVA revealed that the age when the ethanol-exposed pups acquired the ability to hold onto the wire was significantly delayed compared to the control groups (F(2,130) = 3.01; p<.05). As can be observed in Figure 5, this effect of EtOH treatment was mainly driven by the EtOH + Vehicle subjects. Nevertheless, no significant EtOH × Choline interaction was evident on this measure. In contrast, when examining the percent of subjects able to hold onto the wire for 2 consecutive trials/day over the course of testing, ethanol-exposed subjects treated with vehicle were significantly impaired compared to all other groups, including the ethanol-exposed group treated with choline [Fisher’s exact probabilities, p’s<.05].

Figure 5.

Age of first successful grip (A) and percent of subjects successful for 2 trials/day over the course of training (B). Ethanol delayed the ability to grip the bar for 30 seconds. Although ethanol-exposed subjects treated with choline exhibited this behavior earlier, there was no significant interaction of alcohol and choline. In contrast, fewer subjects exposed to ethanol and treated with vehicle were successful for 2 trials/day compared to all other groups, including the ethanol-exposed subjects treated with choline. *** = significantly different from all other groups, ** = significantly different from both control groups

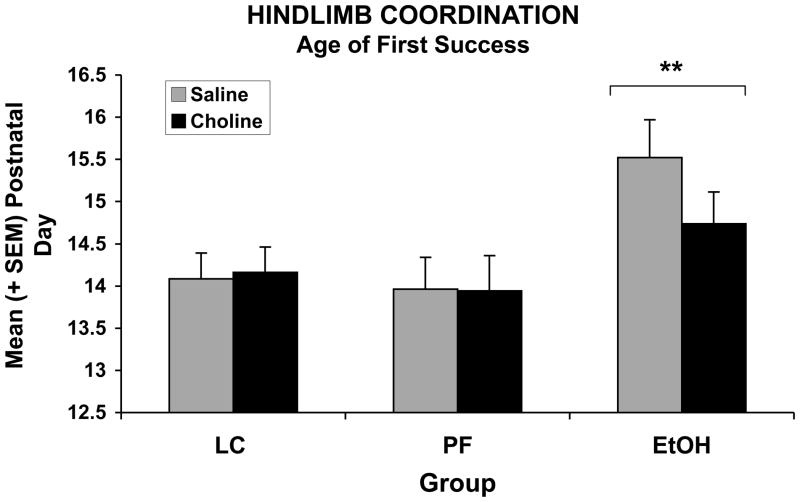

3.6.5 Hindlimb coordination

Prenatal exposure to ethanol significantly delayed the age of first success for hindlimb coordination (Figure 6). Four subjects were never successful (1 EtOH, 1 EtOH + Choline, 1 PF + Choline, and 1 LC + Choline). The ANOVA of the age to first success for the hindlimb coordination test revealed a significant main effect of EtOH [F(2,126) = 5.71; p<.05]. Although prenatal choline supplementation showed a tendency to reduce this deficit in ethanol exposed subjects, no significant interaction was observed.

Figure 6.

Ethanol exposure significantly delayed hindlimb coordination and choline did not significantly mitigate this effect.

** = EtOH significantly different from both control groups

4. Discussion

The present study is the first report that prenatal choline supplementation can prevent some of the adverse consequences of prenatal alcohol exposure on early physical and behavioral development. Specifically, prenatal choline reduced the severity of alcohol-related birth and brain weight deficits, delays in incisor emergence, and alterations in reflex development. These data indicate that nutritional variables may modify the expression of fetal alcohol effects.

First, prenatal choline supplementation significantly attenuated alcohol-related birth weight reductions, but did not significantly influence body weights among controls, consistent with the findings of Meck and colleagues [49]. Interestingly, although there was a trend, choline did not significantly increase body weights among the pair-fed controls, suggesting that choline was not simply mitigating a nutritional deficiency related to food intake, but rather influenced ethanol’s specific effects on physical development. Prenatal choline also increased brain weight at birth among all groups, suggesting that choline influences brain development in both alcohol-exposed and control subjects. One important caveat to this finding is that brain weights at birth were only collected from litters with more than 10 pups. Although there were no differences in the percent of litters sampled from each treatment condition, this finding does overrepresent large litters and it is possible that choline only has this effect when there are a larger number of pups competing for prenatal nutritional factors.

Choline was also effective in mitigating many of ethanol’s effects on physical and reflex development. First, prenatal alcohol led to delays in eye opening and incisor emergence, consistent with previous reports [24,43,65,83]. Although choline did not influence eye opening, it did advance incisor emergence across all groups, ethanol-exposed and control. To our knowledge, this is the first report of changes in physical maturation associated with prenatal choline supplementation. Similar to previous reports, prenatal alcohol exposure also delayed righting reflex [24,56,62], negative geotaxis [27,36], grip strength [27], and motor coordination. In contrast, prenatal alcohol advanced and enhanced cliff avoidance. This differs from some reports of delayed maturation of this reflexive response [56], but it is likely related to increased arousal and/or activity level. Notably, ethanol-exposed subjects eventually performed at control levels. While it is possible that repeated testing and/or handling masked alcohol effects after the first days of testing, many studies suggest that alcohol alters maturation on these tasks, rather than leading to long-lasting impairments. Importantly, choline normalized behavioral development among ethanol-exposed subjects on all measures, with the exception of hindlimb coordination.

Most studies investigating the interactions of nutrition and alcohol have examined the effects of undernutrition as a provocative factor. Several animal studies have shown that the teratogenic effects of alcohol, including low birth weight [90], physical anomalies [88], brain damage [85] and reduced IGF levels [70], are more severe when consumed with suboptimal nutrition; however, often blood alcohol levels are higher among malnourished subjects. Conversely, nutritional supplements can attenuate the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure, although the effectiveness depends on many factors, including the level of alcohol exposure and the outcome measure [87]. The present study indicates that choline is among these supplements. Importantly, choline supplementation did not influence blood alcohol levels, so effects were not related to reductions in fetal alcohol exposure. However, it is not yet known if ethanol leads to changes in choline levels, either by reducing nutritional intake or by altering choline absorption or metabolism. It is possible that ethanol exposure creates a choline deficiency, which could impair brain and behavioral development. Nevertheless, the growing literature on the effects of choline supplementation among non-alcohol-exposed subjects suggests that choline can have beneficial effects on CNS and behavioral development, even when there is no choline deficiency.

Choline plays a number of important roles during development. First, choline contains three methyl groups and, therefore, acts as a methyl donor, influencing the methionine-homocysteine cycle [98]. Choline methylates homocysteine to form methionine; reductions in choline lead to increased homocysteine concentrations, which are associated with increased risk for birth defects [32]. Choline also serves as an epigenetic factor by influencing DNA methylation and subsequent gene expression [41,63]. In addition, choline acts as a precursor to phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, major constituents of cell membranes, allowing choline to influence the structural integrity and signaling functions of cell membranes [96,97]. Finally, choline also acts as a precursor to acetylcholine which not only serves as a neurotransmitter but also a neurotrophic factor. In fact, choline can act directly as a nicotinic receptor agonist [5,6,53]. Thus, choline has several potential modes of action on the developing fetus. Interestingly, prenatal alcohol may influence methionine absorption [64] and DNA methylation [23], can alter neuronal membrane phospholipids profiles [89] and disrupt cholinergic functioning [15,61,73], although choline does not necessarily need to be influencing the same targets as alcohol to alter the course of physical and behavioral development among alcohol-exposed subjects.

Much of what is known of prenatal choline supplementation on brain development is focused on the hippocampus and cortex, areas also known to be adversely affected by prenatal alcohol [7,54]. Choline supplementation from GD 11-17 increases cell division in the neuroepithelial layer of the hippocampus and septum, changes the timing of migration, and increases differentiation of hippocampal neurons [1,2,4,16], leading to long-lasting increases in cell size and basal dendritic arborization in CA1 pyramidal neurons [42]. Prenatal choline supplementation also increases nerve growth factor (NGF) in both the hippocampus and cortex [69], as well as insulin-like growth factor (IGF) 2 and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) I gene expression in the cortex [52]. Long-lasting functional changes are also evident. Perinatal choline supplementation enhances N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor neurotransmission [57], excitability of CA1 pyramidal cells [42], and long-term potentiation (LTP) [37,66] in adult rats. Thus, it is clear that choline supplementation during development can lead to long-lasting changes in hippocampal and cortical function and this is reflected as changes in cognitive performance that are evident even in old age [47].

Unfortunately, the effects of prenatal choline supplementation on other brain regions or the peripheral nervous system have not been extensively examined. The present study suggests that choline may influence neural systems outside the hippocampus, at least in the alcohol-damaged CNS. Although the neural substrates of the reflexes tested in the present study have not been fully elucidated, they do involve motor systems. Interestingly, we have previously reported that choline supplementation during early postnatal development (PD 4-30) reduces the severity of behavioral alterations that rely on the functional integrity of the hippocampus, but not the cerebellum. Specifically, choline failed to improve performance on a parallel bar motor coordination task, in which subjects must traverse two parallel steel rods to a safety platform [79]. However, a study using a mouse model of Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by severe motor dysfunction, reported that choline supplementation in the drinking water of the nursing dams from PD 1-22 improved motor coordination on a rotarod task in males and grip strength in females (there were no effects of choline on controls) [60]. It is likely that the sites of choline’s action depend on the developmental timing of administration and may also depend on the functional integrity of neural systems.

Neuroprotective effects of choline supplementation have been reported with other insults as well. Choline supplementation mitigates the effects of early postnatal maternal separation and undernutrition in rats on emotional and cognitive development [80]. Using slice culture, it has also been shown that choline protects against hippocampal toxicity induced by NMDA as well as cortisol-related exacerbation of NMDA-induced toxicity [58]. Not only is choline neuroprotective during an insult, but perinatal choline has also been shown to protect against neuropathology even when administered weeks before the insult. For example, prenatal choline supplementation protects against neurotoxicity induced by MK-801, an NMDA receptor antagonist, administered during adolescence [25] or adulthood [26], as well as seizure-induced neurotoxicity in 40-day-old rats [94]. Conversely, choline supplementation may also have beneficial effects when administered after an insult. Holmes et al (2002) [33] demonstrated that four weeks of choline supplementation was neuroprotective when administered immediately after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Similarly, we have shown that choline supplementation that commences after early alcohol exposure reduces the severity of cognitive deficits [74,81]. Thus, it is clear that choline supplementation can protect against a variety of insults at various developmental stages.

In sum, these data illustrate that prenatal choline supplementation may effectively reduce the severity of some fetal alcohol effects, both physical and behavioral. These findings suggest that choline supplementation may effectively protect against ethanol’s teratogenic effects, an important finding in the search to prevent the adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIAAA grant AA12446.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement for Authors

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest related to this project.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Albright CD, Friedrich CB, Brown EC, Mar MH, Zeisel SH. Maternal dietary choline availability alters mitosis, apoptosis and the localization of TOAD-64 protein in the developing fetal rat septum. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;115:123–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright CD, Mar MH, Craciunescu CN, Song J, Zeisel SH. Maternal dietary choline availability alters the balance of netrin-1 and DCC neuronal migration proteins in fetal mouse brain hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;159:149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albright CD, Tsai AY, Friedrich CB, Mar MH, Zeisel SH. Choline availability alters embryonic development of the hippocampus and septum in the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;113:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albright CD, Tsai AY, Mar MH, Zeisel SH. Choline availability modulates the expression of TGFbeta1 and cytoskeletal proteins in the hippocampus of developing rat brain. Neurochem Res. 1998;23:751–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1022411510636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albuquerque EX, Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Castro NG, Schrattenholz A, Barbosa CT, Bonfante-Cabarcas R, Aracava Y, Eisenberg HM, Maelicke A. Properties of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: pharmacological characterization and modulation of synaptic function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:1117–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Cortes WS, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Choline is a selective agonist of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat brain neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:2734–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman RF, Hannigan JH. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the hippocampus: spatial behavior, electrophysiology, and neuroanatomy. Hippocampus. 2000;10:94–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<94::AID-HIPO11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, Biotin, and choline. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonthius DJ, Karacay B, Dai D, Pantazis NJ. FGF-2, NGF and IGF-1, but not BDNF, utilize a nitric oxide pathway to signal neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects against alcohol toxicity in cerebellar granule cell cultures. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;140:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SY, Charness ME, Wilkemeyer MF, Sulik KK. Peptide-mediated protection from ethanol-induced neural tube defects. Dev Neurosci. 2005;27:13–9. doi: 10.1159/000084528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SY, Dehart DB, Sulik KK. Protection from ethanol-induced limb malformations by the superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic, EUK-134. Faseb J. 2004;18:1234–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0850fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng RK, Meck WH, Williams CL. alpha7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and temporal memory: synergistic effects of combining prenatal choline and nicotine on reinforcement-induced resetting of an interval clock. Learn Mem. 2006;13:127–34. doi: 10.1101/lm.31506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarren SK, Randels SP, Sanderson M, Fineman RM. Screening for fetal alcohol syndrome in primary schools: a feasibility study. Teratology. 2001;63:3–10. doi: 10.1002/1096-9926(200101)63:1<3::AID-TERA1001>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen-Kerem R, Koren G. Antioxidants and fetal protection against ethanol teratogenicity. I. Review of the experimental data and implications to humans. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa LG, Guizzetti M. Muscarinic cholinergic receptor signal transduction as a potential target for the developmental neurotoxicity of ethanol. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:721–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craciunescu CN, Albright CD, Mar MH, Song J, Zeisel SH. Choline availability during embryonic development alters progenitor cell mitosis in developing mouse hippocampus. J Nutr. 2003;133:3614–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endres M, Toso L, Roberson R, Park J, Abebe D, Poggi S, Spong CY. Prevention of alcohol-induced developmental delays and learning abnormalities in a model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1028–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher MC, Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Sadler TW. Inhibitors of choline uptake and metabolism cause developmental abnormalities in neurulating mouse embryos. Teratology. 2001;64:114–22. doi: 10.1002/tera.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher MC, Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Sadler TW. Perturbations in choline metabolism cause neural tube defects in mouse embryos in vitro. Faseb J. 2002;16:619–21. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0564fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabriel KI, Johnston S, Weinberg J. Prenatal ethanol exposure and spatial navigation: effects of postnatal handling and aging. Dev Psychobiol. 2002;40:345–57. doi: 10.1002/dev.10023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallo PV, Weinberg J. Neuromotor development and response inhibition following prenatal ethanol exposure. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1982;4:505–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garro AJ, McBeth DL, Lima V, Lieber CS. Ethanol consumption inhibits fetal DNA methylation in mice: implications for the fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:395–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottesfeld Z, Silverman PB. Developmental delays associated with prenatal alcohol exposure are reversed by thyroid hormone treatment. Neurosci Lett. 1990;109:42–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90535-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo-Ross SX, Clark S, Montoya DA, Jones KH, Obernier J, Shetty AK, White AM, Blusztajn JK, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal choline supplementation protects against postnatal neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-j0005.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo-Ross SX, Jones KH, Shetty AK, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal dietary choline availability alters postnatal neurotoxic vulnerability in the adult rat. Neurosci Lett. 2003;341:161–3. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannigan JH. Effects of prenatal exposure to alcohol plus caffeine in rats: pregnancy outcome and early offspring development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:238–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannigan JH, O’Leary-Moore SK, Berman RF. Postnatal environmental or experiential amelioration of neurobehavioral effects of perinatal alcohol exposure in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heaton MB, Mitchell JJ, Paiva M. Amelioration of ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in the neonatal rat central nervous system by antioxidant therapy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:512–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heaton MB, Mitchell JJ, Paiva M. Overexpression of NGF ameliorates ethanol neurotoxicity in the developing cerebellum. J Neurobiol. 2000;45:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaton MB, Paiva M, Swanson DJ, Walker DW. Modulation of ethanol neurotoxicity by nerve growth factor. Brain Res. 1993;620:78–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90273-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobbs CA, Cleves MA, Melnyk S, Zhao W, James SJ. Congenital heart defects and abnormal maternal biomarkers of methionine and homocysteine metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:147–53. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmes GL, Yang Y, Liu Z, Cermak JM, Sarkisian MR, Stafstrom CE, Neill JC, Blusztajn JK. Seizure-induced memory impairment is reduced by choline supplementation before or after status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2002;48:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holson RR, Pearce B. Principles and pitfalls in the analysis of prenatal treatment effects in multiparous species. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992;14:221–8. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90020-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, Kodituwakku P, Gossage JP, Trujillo PM, Buckley DG, Miller JH, Aragon AS, Khaole N, et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics. 2005;115:39–47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janicke B, Coper H. The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the behavior of rats during their life span. Journal of Gerontology. 1993;48:156–167. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.b156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones JP, Meck WH, Williams CL, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Choline availability to the developing rat fetus alters adult hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;118:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kable JA, Coles CD, Taddeo E. Socio-cognitive habilitation using the math interactive learning experience program for alcohol-affected children. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1425–2434. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly SJ, Hulsether SA, West JR. Alterations in sensorimotor development: relationship to postnatal alcohol exposure. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1987;9:243–51. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(87)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klintsova AY, Scamra C, Hoffman M, Napper RM, Goodlett CR, Greenough WT. Therapeutic effects of complex motor training on motor performance deficits induced by neonatal binge-like alcohol exposure in rats: II. A quantitative stereological study of synaptic plasticity in female rat cerebellum. Brain Res. 2002;937:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovacheva VP, Mellott TJ, Davison JM, Wagner N, Lopez-Coviella I, Schnitzler AC, Blusztajn JK. Gestational choline deficiency causes global and Igf2 gene DNA hypermethylation by up-regulation of Dnmt1 expression. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31777–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Q, Guo-Ross S, Lewis DV, Turner D, White AM, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Dietary prenatal choline supplementation alters postnatal hippocampal structure and function. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1545–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.00785.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-Tejero D, Ferrer I, Herrera LLME. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on physical growth, sensory reflex maturation and brain development in the rat. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1986;12:251–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1986.tb00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marino MD, Aksenov MY, Kelly SJ. Vitamin E protects against alcohol-induced cell loss and oxidative stress in the neonatal rat hippocampus. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22:363–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.May PA, Gossage JP. Estimating the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome. A summary. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:159–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McAlhany RE, Jr, West JR, Miranda RC. Glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) prevents ethanol-induced apoptosis and JUN kinase phosphorylation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:209–16. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCann JC, Hudes M, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relationship between dietary availability of choline during development and cognitive function in offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:696–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKeon-O’Malley C, Siwek D, Lamoureux JA, Williams CL, Kowall NW. Prenatal choline deficiency decreases the cross-sectional area of cholinergic neurons in the medial septal nucleus. Brain Res. 2003;977:278–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02599-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meck WH, Smith RA, Williams CL. Pre- and postnatal choline supplementation produces long-term facilitation of spatial memory. Dev Psychobiol. 1988;21:339–53. doi: 10.1002/dev.420210405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meck WH, Williams CL. Metabolic imprinting of choline by its availability during gestation: implications for memory and attentional processing across the lifespan. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:385–399. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meck WH, Williams CL. Simultaneous temporal processing is sensitive to prenatal choline availability in mature and aged rats. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3045–51. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709290-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mellott TJ, Follettie MT, Diesl V, Hill AA, Lopez-Coviella I, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal choline availability modulates hippocampal and cerebral cortical gene expression. Faseb J. 2007;21:1311–23. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6597com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mike A, Castro NG, Albuquerque EX. Choline and acetylcholine have similar kinetic properties of activation and desensitization on the alpha7 nicotinic receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2000;882:155–68. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02863-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller MW. Effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol on neocortical development: II. Cell proliferation in the ventricular and subventricular zones of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;287:326–38. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell JJ, Paiva M, Heaton MB. The antioxidants vitamin E and beta-carotene protect against ethanol-induced neurotoxicity in embryonic rat hippocampal cultures. Alcohol. 1999;17:163–8. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molina JC, Hoffman H, Spear LP, Spear NE. Sensorimotor maturation and alcohol responsiveness in rats prenatally exposed to alcohol during gestational day 8. Neurotox Teratol. 1987;9:121–128. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(87)90088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montoya D, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal choline supplementation alters hippocampal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated neurotransmission in adult rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;296:85–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01660-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mulholland PJ, Self RL, Harris BR, Littleton JM, Prendergast MA. Choline exposure reduces potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate toxicity by corticosterone in the developing hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;153:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.NIAAA. 10th Special Report to US Congress on Alcohol and Health. National Institute of Health; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nag N, Berger-Sweeney JE. Postnatal dietary choline supplementation alters behavior in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagahara AH, Handa RJ. Fetal alcohol-exposed rats exhibit differential response to cholinergic drugs on a delay-dependent memory task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1999;72:230–43. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ness JW, Franchina JJ. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on rat pups’ ability to elicit retrieval behavior from dams. Dev Psychobiol. 1990;23:85–99. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Niculescu MD, Craciunescu CN, Zeisel SH. Dietary choline deficiency alters global and gene-specific DNA methylation in the developing hippocampus of mouse fetal brains. Faseb J. 2006;20:43–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4707com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polache A, Martin-Algarra RV, Guerri C. Effects of chronic alcohol consumption on enzyme activities and active methionine absorption in the small intestine of pregnant rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1237–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Potter BM, Berntson GG. Prenatal alcohol exposure: effects on acoustic startle and prepulse inhibition. Neurotox Teratol. 1987;9:17–21. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(87)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pyapali GK, Turner DA, Williams CL, Meck WH, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal dietary choline supplementation decreases the threshold for induction of long-term potentiation in young adult rats. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1790–6. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riley EP, McGee CL. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview with emphasis on changes in brain and behavior. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:357–65. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Little RE, Clarren SK, Dehaene P, Hanson JW, Graham JM., Jr Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Teratology. 1997;56:317–26. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199711)56:5<317::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sandstrom NJ, Loy R, Williams CL. Prenatal choline supplementation increases NGF levels in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of young and adult rats. Brain Res. 2002;947:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shankar K, Hidestrand M, Liu X, Xiao R, Skinner CM, Simmen FA, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. Physiologic and genomic analyses of nutrition-ethanol interactions during gestation: Implications for fetal ethanol toxicity. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:1379–97. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Yang W, Selvin S, Schaffer DM. Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betaine and neural tube defects in offspring. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:102–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O’Malley K, Young JK. Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:228–38. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Swanson DJ, King MA, Walker DW, Heaton MB. Chronic prenatal ethanol exposure alters the normal ontogeny of choline acetyltransferase activity in the rat septohippocampal system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1252–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas JD, Biane JS, O’Bryan KA, O’Neill TM, Dominguez HD. Choline supplementation following third-trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure attenuates behavioral alterations in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:120–30. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas JD, Fleming Sl, Riley EP. MK-801 can exacerbate or attenuate behavioral alterations associated with neonatal alcohol exposure in the rat, depending on the timing of administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:764–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomas JD, Garcia GG, Dominguez HD, Riley EP. Administration of eliprodil during ethanol withdrawal in the neonatal rat attenuates ethanol-induced learning deficits. Psychopharmacology. 2004;175:189–195. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomas JD, Garrison M, O’Neill TM. Perinatal choline supplementation attenuates behavioral alterations associated with neonatal alcohol exposure in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomas JD, La Fiette MH, Quinn VR, Riley EP. Neonatal choline supplementation ameliorates the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on a discrimination learning task in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:703–11. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thomas JD, O’Neill TM, Dominguez HD. Perinatal choline supplementation does not mitigate motor coordination deficits associated with neonatal alcohol exposure in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tonjes R, Hecht K, Brautzsch M, Lucius R, Dorner G. Behavioural changes in adult rats produced by early postnatal maternal deprivation and treatment with choline chloride. Experimental and clinical endocrinology. 1986;88:151–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1210590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tran T, Thomas JD. Perinatal choline supplementation mitigates trace eyeblink conditioning deficits associated with 3rd trimester alcohol exposure in rats. Society for Neuroscience; San Diego, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vink J, Auth J, Abebe DT, Brenneman DE, Spong CY. Novel peptides prevent alcohol-induced spatial learning deficits and proinflammatory cytokine release in a mouse model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:825–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vorhees CV, Fernandez K. Effects of short-term prenatal alcohol exposure on maze, activity, and olfactory orientation performance in rats. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1986;8:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wagner AF, Hunt PS. Impaired trace fear conditioning following neonatal ethanol: reversal by choline. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:482–7. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wainwright P, Fritz G. Effect of moderate prenatal ethanol exposure on postnatal brain and behavioral development in BALB/c mice. Exp Neurol. 1985;89:237–49. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Warren KR, Calhoun FJ, May PA, Viljoen DL, Li TK, Tanaka H, Marinicheva GS, Robinson LK, Mundle G. Fetal alcohol syndrome: an international perspective. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:202S–206S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weinberg J. Effects of ethanol and maternal nutritional status on fetal development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1985;9:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weinberg J, D’Alquen G, Bezio S. Interactive effects of ethanol intake and maternal nutritional status on skeletal development of fetal rats. Alcohol. 1990;7:383–8. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90020-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wen Z, Kim HY. Alterations in hippocampal phospholipid profile by prenatal exposure to ethanol. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1368–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wiener SG, Shoemaker WJ, Koda LY, Bloom FE. Interaction of ethanol and nutrition during gestation: influence on maternal and offspring development in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;216:572–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilkemeyer MF, Chen SY, Menkari CE, Brenneman DE, Sulik KK, Charness ME. Differential effects of ethanol antagonism and neuroprotection in peptide fragment NAPVSIPQ prevention of ethanol-induced developmental toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8543–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wilkemeyer MF, Menkari CE, Spong CY, Charness ME. Peptide antagonists of ethanol inhibition of l1-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2002;303:110–116. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams CL, Meck WH, Heyer DD, Loy R. Hypertrophy of basal forebrain neurons and enhanced visuospatial memory in perinatally choline-supplemented rats. Brain Res. 1998;794:225–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang Y, Liu Z, Cermak JM, Tandon P, Sarkisian MR, Stafstrom CE, Neill JC, Blusztajn JK, Holmes GL. Protective effects of prenatal choline supplementation on seizure-induced memory impairment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0006.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zeisel SH. Choline: critical role during fetal development and dietary requirements in adults. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006;26:229–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zeisel SH. The fetal origins of memory: the role of dietary choline in optimal brain development. J Pediatr. 2006;149:S131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeisel SH, Blusztajn JK. Choline and human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:269–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zeisel SH, Niculescu MD. Perinatal choline influences brain structure and function. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou FC, Sari Y, Powrozek TA, Spong CY. A neuroprotective peptide antagonizes fetal alcohol exposure-compromised brain growth. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;24:189–99. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:2:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]