Abstract

Glutamine is an essential nutrient for cancer cells. In this issue of Cancer Cell, Wang et al. show that malignant transformation by Rho GTPases leads to activation of glutaminase, which converts glutamine to glutamate to fuel cancer cell metabolism. Inhibition of glutaminase by a small compound effectively suppresses oncogenic transformation.

It has been known for a long time that cancer cells have elevated aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) and exhibit increased dependency on glutamine for growth and proliferation. The active utilization of glucose by cancer cells constitutes the biochemical basis for 18fluoro-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) used in clinical diagnose of cancer. Glutamine, although classified as a non-essential amino acid, is known for decades to be a key ingredient in the culture medium to support cancer cell growth. However, the molecular mechanisms that link malignant transformation and altered metabolism remain to be elucidated. Recent studies have revealed some of the underlying mechanisms. For instance, both HIF-1 and c-Myc have been shown to transcriptionally upregulate multiple glycolytic enzymes, while the enhancement of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) by HIF1 leads to inhibition of pyruvate entry into the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) through phosphorylation and inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (Dang et al., 2008). AKT activation is known to promote membrane localization of glucose transporters (GLUTs), activate phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK2), and increase hexokinase II association with mitochondria to facilitate glucose uptake (Robey and Hay, 2009). The tumor suppressor p53 exerts its effect on energy metabolism by regulating PGM, TIGAR, and SCO2 (Shaw, 2006). The increased dependency of cancer cells on glycolysis has been considered as the Achilles heel that may be targeted for therapeutic purpose (Pelicano et al., 2006).

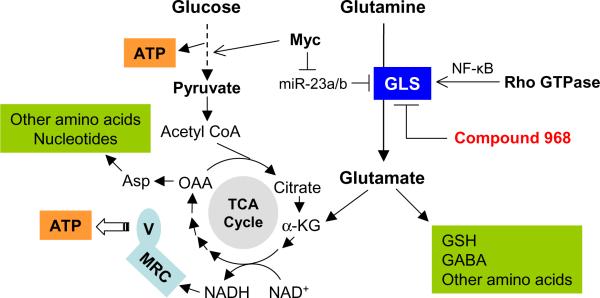

Although the glycolytic pathway generates ATP and produces metabolic intermediates for cancer cells, glucose can only provide carbon source. Glutamine is another essential nutrient for cancer cells, and is an abundant amino acid in the serum. Essential functions of glutamine include its conversion to glutamate as a metabolic intermediate to be channeled into the TCA cycle, and its function as a precursor for the biosynthesis of nucleic acids, certain amino acids, and glutathione (Figure 1). The mitochondrial enzyme glutaminase (GLS) catalyzes the conversion of glutamine to glutamate. Increased expression of glutaminase is often observed in tumor and rapidly dividing cells. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that c-Myc enhanced GLS expression through suppression of miR-23a/b (Gao et al., 2009), thus providing a molecular link between oncogenic signal and glutamine metabolism.

Figure 1.

Effect of oncogenic signals on glutamine metabolism through regulation of glutaminase. The interconnection between glutamine metabolism and glucose metabolism is also shown. Inhibition of glutaminase by compound 968 suppresses oncogenic transformation induced by Rho GTPases. GLS, glutaminase; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; MRC, mitochondrial respiratory chain; V, mitochondrial respiratory complex V; OAA, oxaloacetate; Asp, aspartate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate.

In this issue of Cancer Cell, Wang et al report the identification of another class of oncogenic molecules, Rho GTPases, which can promote glutamine metabolism through activation of glutaminase in a NF-κB-dependent manner (Wang, et al., 2010). Using a focus-formation assay to screen for compounds that might suppress the transforming capacity of Rho GTPases activated by the oncogenic molecule Dbl (Diffused B cell lymphoma), the authors identified a tetrahydrobenzo[a] derivative (compound 968) capable of blocking Rho GTPase-induced transformation in fibroblasts and inhibiting cancer cell growth. They then used a biotinylated compound in combination with streptavidin beads to pull down the molecules that bind to the active moiety of compound 968, and identified the target protein as the mitochondrial glutaminase (kidney-type, or KGA). Specific knocking down of KGA by siRNA suppressed colony-formation of cells with constitutively activated Rho GTPase and strongly inhibited breast cancer cell proliferation in soft agar, confirming the important role of glutaminase in cancer cell metabolism. The authors further showed that glutaminase activity was elevated in Dbl-transformed cells, and that such increase in the enzyme activity was NF-κB-dependent, likely through affecting the expression of a yet unidentified molecule that might promote the phosphorylation of glutaminase. Interestingly, when cells were supplied with a cell-permeable analog of α-ketoglutarate, the inhibitory effect of compound 968 was reversed, suggesting that the conversion of glutamine to glutamate then to α-ketoglutarate for replenishment of the TCA cycle may be critical for cancer cell growth.

The work by Wang et al and the results from another study (Gao et al., 2009) suggest that different oncogenic signals (Rho GTPase and c-Myc) may cause similar metabolic consequences through activation of glutaminase, leading to an increase in glutamine utilization by cancer cells. Interestingly, two recent studies showed that the tumor suppressor p53 could transcriptionally activate the liver-type glutaminase (GLS2), promoting glutamine metabolism and glutathione generation (Hu et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2010). The authors suggested that the increase in antioxidant capacity due to elevated glutathione might contribute to the tumor suppression function of p53. Since GLS and GLS2 have different enzyme kinetics and may be subjected to different regulatory mechanisms, the roles of these two types of glutaminases in cancer metabolism required further investigation. Nevertheless, the elevated glutamine catabolism appeared to play a major role in supporting malignant transformation, since suppression of glutaminase by the chemical inhibitor 968 or siRNA strongly blocked the oncogene-induced transformation. As such, the increased glutamine consumption by cancer cells should not be considered merely as a metabolic symptom or a by-product of transformation.

Since glutamine can be metabolized to produce ATP or function as a precursor for the synthesis of protein, nucleotides, and lipid (DeBerardinis et al., 2007), it is important to determine if inhibition of glutaminase would lead to ATP depletion or suppression of biomass synthesis. Furthermore, since glucose, through glycolysis and the TCA cycle, can also provide ATP and metabolic intermediates as the building blocks for cancer cells (Figure 1), it would be interesting to test what impact of Rho-GTPase activation might have on glucose metabolism and determine the relative roles of these two nutrients in fueling the transformed cells. To the cancer cells, is glutamine sweeter than glucose? The answer to this question is likely cell context-dependent. The metabolic profiles of different cancer cells may likely be determined by their genotypes and the microenvironment they reside. For instance, c-Myc may promote both glucose and glutamine utilization due to its ability to upregulate the glycolytic enzymes and to activate GLS. In contrast, certain papillomavirus-transformed cervical cancer cells (HeLa) may mainly use glutamine as the major energy source (Reitzer et al., 1979). Thus, a detail understanding of the complex effect of oncogenic signals and tissue microenvironment on cancer cell metabolism is essential for the design of effective metabolic intervention strategies for different types of cancers. Targeting cancer metabolism seems to hold great promise for cancer treatment and has been gaining momentum in the recent years. It is important to identify the critical molecules that are preferentially used by cancer cells to maintain their altered metabolism and are not essential for the normal cells. The study by Wang et al suggests that glutaminase seems to be a promising therapeutic target. Pre-clinical and clinical studies are required to further test this possibility.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Dang CV, Kim JW, Gao P, Yustein J. The interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, Dang CV. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–U100. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Zhang C, Wu R, Sun Y, Levine A, Feng Z. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7455–7460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelicano H, Martin DS, Xu RH, Huang P. Glycolysis inhibition for anticancer treatment. Oncogene. 2006;25:4633–4646. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzer LJ, Wice BM, Kennell D. Evidence that glutamine, not sugar, is the major energy source for cultured HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:2669–2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey RB, Hay N. Is Akt the “Warburg kinase”?-Akt-energy metabolism interactions and oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ. Glucose metabolism and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:598–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Tanaka T, Poyurovsky MV, Nagano H, Mayama T, Ohkubo S, Lokshin M, Hosokawa H, Nakayama T, Suzuki Y, et al. Phosphate-activated glutaminase (GLS2), a p53-inducible regulator of glutamine metabolism and reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7461–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J-B, Erickson JW, Fuji R, Ramachandran S, Gao P, Dinavah R, Wilson KF, Ambrosio ALB, Dias SMG, Dang CV, Cerione RA. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.009. This issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]