Abstract

The current epidemics of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) all represent insulin-resistance diseases. Previous studies showed that streptozotocin, a nitrosamine-related compound, causes insulin resistance diseases including, T2DM, NASH, and AD-type neurodegeneration. We hypothesize that chronic human exposure to nitrosamine compounds, which are widely present in processed foods, contributes to the pathogenesis of T2DM, NASH, and AD. Long Evans rat pups were treated with N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA) by i.p. (x3) or i.c. (x1) injection, and 2–4 weeks later, they were evaluated for cognitive-motor dysfunction, insulin resistance, and neurodegeneration using behavioral, biochemical, and molecular approaches. NDEA treatment caused T2DM, NASH, deficits in motor function and spatial learning, and neurodegeneration characterized by insulin resistance and deficiency, lipid peroxidation, cell loss, increased levels of amyloid-β protein precursor-amyloid-β, phospho-tau, and ubiquitin immunoreactivities, and upregulated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine and pro-ceramide genes, which together promote insulin resistance. In conclusion, environmental and food contaminant exposures to nitrosamines play critical roles in the pathogenesis of major insulin resistance diseases including T2DM, NASH, and AD. Improved detection and prevention of human exposures to nitrosamines will lead to earlier treatments and eventual quelling of these costly and devastating epidemics.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, environmental toxin, neurodegeneration, nitrosamine, obesity

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence rates of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which includes metabolic syndrome, have increased exponentially over the past several decades, and thus far show few hints of plateau [1–6]. The relatively short time interval associated with dramatic shifts in age-adjusted AD morbidity and mortality is consistent with an exposure-related rather than genetic etiology. We have noted that the striking increases in AD mortality rates corrected for age, have given chase to the sharply increased consumption of processed foods, use of preservatives, and demand for nitrogen-containing fertilizers [7]. A common theme resonating from these unnecessary lifestyle trends is that we have inadvertently increased our chronic exposures to nitrosamines (R1N(-R2)-N=O) and related compounds.

Nitrosamines form by chemical reactions between nitrites and secondary amines or proteins. Nitrosamines exert their toxic and mutagenic effects by alkylating N-7 of guanine, leading to increased DNA damage [8], and generation of reactive oxygen species such as superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which result in increased lipid peroxidation, protein adduct formation, and pro-inflammatory cytokine activation [9]. However, these very same molecular and biochemical pathogenic cascades are associated with major human insulin-resistance diseases, including T2DM, NASH, and AD [10–16]. The concept that chronic injury caused by exposure to alkylating agents could result in malignancy and/or tissue degeneration is not far-fetched given the facts that: 1) chronic exposure to tobacco nitrosamines causes both lung cancer and emphysema with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and 2) exposures to streptozotocin (STZ), a nitrosamine-related compound, can cause hepatocellular or pancreatic carcinoma, T2DM, AD-type neurodegeneration, or hepatic steatosis, depending on dose and route of administration [17–25]. Therefore, although research on nitrosamine-related compounds has been largely focused on their mutagenic properties, thorough characterization of their non-neoplastic and degenerative effects is clearly warranted. In this regard, guidance may be obtained from what is already known about STZ-induced disease.

STZ, like other N-nitroso compounds, causes cellular injury and disease by functioning as: 1) an alkylating agent and potent mutagen [17]; 2) an inducer of DNA adducts, including N7-methylguanine, which lead to increased apoptosis [26]; 3) a mediator of unscheduled DNA synthesis, triggering cell death [17]; 4) an inducer of single-strand DNA breaks and stimulus for nitric oxide (NO) formation following breakdown of its nitrosamine group [19]; and 5) an enhancer of the xanthine oxidase system leading to increased production of superoxide anion, H2O2, and OH− radicals [27]. Ultimately, STZ-induced cellular injury, DNA damage, and oxidative stress cause mitochondrial dysfunction [19], ATP deficiency [28], poly-ADP ribosylation, and finally apoptotic cell death. The structural similarities between STZ and nitrosamines, including N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA) and N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) [29], together with experimental evidence that high doses of STZ cause cancer while lower doses cause diabetes or AD-type neurodegeneration with cognitive impairment [18, 19, 25], led us to hypothesize that while high doses of environmental and consumed nitrosamines cause cancer, exposure to lower, sub-mutagenic doses may promote insulin-resistance mediated degenerative diseases, including T2DM, NASH, and AD. The present study examines this hypothesis using an in vivo experimental animal model in which rats were exposed to sub-mutagenic doses of NDEA.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Experimental model

Postnatal day 3 (P3) Long Evans rat pups (mean body weight 10 g) were given a single intra-cerebral (i.c.) injection of 10 μg NDEA or vehicle using previously described methods [22,25], or 3 alternate day intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injections of 20 μg NDEA or vehicle. Upon recovery (usually within 30 seconds), the pups were returned to their dams, monitored daily, and weighed weekly. The NDEA doses were selected based on in vitro neurotoxicity studies demonstrating threshold concentrations required to cause minimal impairment of neuronal mitochondrial function, promote oxidative stress, and increase indices of neurodegeneration [30]. In addition, exploratory in vivo studies demonstrated that the protocol used had no immediate effects on behavior and did not cause mortality. On P15–P16, rats were subjected to rotarod testing of motor function, and from P25 to P28, they were subjected to Morris water maze testing of spatial learning and memory [22,25]. 5–6 rats per group were sacrificed on P10 or P17 by i.p. injection of pentobarbital (120 mg/kg) to monitor brain growth. On P30, following an overnight fast, the remaining rats (12–20 per group) were sacrificed. Blood was harvested prior to death to measure glucose, insulin, cholesterol, triglyceride, and free fatty acid levels as previously described [31,32]. Pancreas, liver, and brain were harvested immediately postmortem. Tissue samples of liver and pancreas were immersion fixed in Histochoice (Amresco, Solon, OH) and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections (5-μm thick) were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and examined under code. Pancreatic islet cross sectional areas were measured using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD), and results were used to calculate mean islet diameters in each specimen. Samples of liver were snap-frozen in a dry ice-methanol bath and stored at −80°C for molecular and biochemical assays of gene expression, lipid content, immunoreactivity, or receptor binding.

The cerebral hemispheres were sectioned in the coronal plane along standardized landmarks [22,25,31,32]. A 3-mm thick block of temporal lobe (level of hypothalamus and infundibulum), and half the cerebellum (sectioned in the mid-sagittal plane) were snap frozen and stored at −80°C for later assays of gene expression, immunoreactivity, and receptor binding. The remaining brain tissue was immersion fixed in Histochoice and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections (8-μm thick) were stained with H&E and examined under code. Adjacent sections were used for immunohistochemical staining to detect glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), ubiquitin, or 4-hydroxy-2-nonenol (HNE) immunoreactivity as indices of neurodegeneration. The brain analyses were focused on the temporal lobe and cerebellum because: 1) these regions require intact insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling mechanisms to maintain their structural and functional integrity [33,34]; 2) both are severely damaged by i.c.-STZ mediated neurodegeneration [22, 25]; and 3) the temporal lobe is a major target of neurodegeneration in AD [34]. Our experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Lifespan-Rhode Island Hospital, and it conforms to the guidelines set by the National Institutes of Health.

Rotarod testing

We used rotarod testing to assess long-term motor deficits [35] resulting from the NDEA treatments. On P15, rats were trained to remain balanced on the rotating Rotamex-5 apparatus (Columbus Instruments) at 5 rpm. On P16, rats were administered 10 trials at incremental speeds from 5 to 10 rpm, with 10 min rest between each trial. The latency to fall was automatically detected and recorded with photocells placed over the rod. However, trials were stopped after 30 seconds to avoid exercise fatigue. Data from trials 3–6 (5–7 rpm) and 7–10 (8–10 rpm) were culled and analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test for significance.

Morris water maze testing

A standard Morris water maze was used to measure learning [36]. On the first day of testing, the rats were oriented to the water maze and educated about the location of the platform. On the 3 subsequent days of testing, the platform was submerged just below the surface, and rats were tested for learning and memory by measuring the latency period required to reach and recognize the platform. The rats were allowed 120 seconds to locate the platform, after which they were guided to it. After landing on the platform, the rats were allowed to orient themselves for 15 seconds prior to being rescued. The rats were tested three times each day, with 30 min intervals between trials. The rats were placed in the same quadrant of the water maze for every trial on Days 1 and 2, but on subsequent days, the start locations were randomized to test mastery of spatial learning and memory. Data from all 3 trials on each day were analyzed by calculating the area under the curve corresponding to latency for locating and landing on the platform. Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test for significance.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assays of gene expression

RNA isolated from tissue was reverse transcribed using random primers, and the resulting cDNA templates were used in PCR amplification reactions with gene specific primers listed in Table 1. Amplified signals were detected and analyzed in triplicate using the Mastercycler ep realplex instrument and software (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) [31]. Relative mRNA abundance was calculated from the ng ratios of specific mRNA to 18S measured in the same samples, and those data were used for inter-group statistical comparisons. Control studies included analysis of: 1) template-free reactions; 2) RNA that had not been reverse transcribed; 3) RNA samples pre-treated with DNAse I; 4) samples treated with RNAse A prior to the reverse transcriptase reaction; and 5) genomic DNA.

Table 1.

Primer Pairs Used for qRT-PCR Assays

| Primer* | Direction | Sequence (5′→3′) | Position (mRNA) | Amplicon Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | For | TTC TAC ACA CCC AAG TCC CGT C | 145 | 135 |

| Insulin | Rev | ATC CAC AAT GCC ACG CTT CTG C | 279 | |

| Insulin Receptor | For | TGA CAA TGA GGA ATG TGG GGA C | 875 | 129 |

| Insulin Receptor | Rev | GGG CAA ACT TTC TGA CAA TGA CTG | 1003 | |

| IGF-I | For | GAC CAA GGG GCT TTT ACT TCA AC | 65 | 127 |

| IGF-I | Rev | TTT GTA GGC TTC AGC GGA GCA C | 191 | |

| IGF-I Receptor | For | GAA GTC TGC GGT GGT GAT AAA GG | 2138 | 113 |

| IGF-I Receptor | Rev | TCT GGG CAC AAA GAT GGA GTT G | 2250 | |

| IGF-II | For | CCA AGA AGA AAG GAA GGG GAC C | 763 | 95 |

| IGF-II | Rev | GGC GGC TAT TGT TGT TCA CAG C | 857 | |

| IGF-II Receptor | For | TTG CTA TTG ACC TTA GTC CCT TGG | 1066 | 91 |

| IGF-II Receptor | Rev | AGA GTG AGA CCT TTG TGT CCC CAC | 1156 | |

| IRS-1 | For | GAT ACC GAT GGC TTC TCA GAC G | 604 | 134 |

| IRS-1 | Rev | TCG TTC TCA TAA TAC TCC AGG CG | 737 | |

| IRS-2 | For | CAA CAT TGA CTT TGG TGA AGG GG | 255 | 109 |

| IRS-2 | Rev | TGA AGC AGG ACT ACT GGC TGA GAG | 263 | |

| IRS-4 | For | ACC TGA AGA TAA GGG GTC GTC TGC | 2409 | 132 |

| IRS-4 | Rev | TGT GTG GGG TTT AGT GGT CTG G | 2540 | |

| Hu | For | CAC TGT GTG AGG GTC CAT CTT CTG | 271 | 50 |

| Hu | Rev | TCA AGC CAT TCC ACT CCA TCT G | 320 | |

| MAG-1 | For | AAC CTT CTG TAT CAG TGC TCC TCG | 18 | 63 |

| MAG-1 | Rev | CAG TCA ACC AAG TCT CTT CCG TG | 80 | |

| GFAP | For | TGG TAA AGA CGG TGG AGA TGC G | 1245 | 200 |

| GFAP | Rev | GGC ACT AAA ACA GAA GCA AGG GG | 1444 | |

| AIF-1 | For | GGA TGG GAT CAA CAA GCA CT | 168 | 158 |

| AIF-1 | Rev | GTT TCT CCA GCA TTC GCT TC | 325 | |

| IL-1β | For | CAG CAG CAT CTC GAC AAG AG | 233 | 60 |

| IL-1β | Rev | CTT CTC CAC AGC CAC AAT GA | 292 | |

| TNF-α | For | ATG TGG AAC TGG CAG AGG AG | 26 | 84 |

| TNF-α | Rev | AGA AGA GGC TGA GGC ACA GA | 109 | |

| IL-6 | For | ATG TTG TTG ACA GCC ACT GC | 116 | 51 |

| IL-6 | Rev | GTC TCC TCTCCG GAC TTG TG | 166 | |

| ChAT | For | TCA CAG ATG CGT TTC ACA ACT ACC | 478 | 106 |

| ChAT | Rev | TGG GAC ACA ACA GCA ACC TTG | 583 | |

| AChE | For | TTC TCC CAC ACC TGT CCT CAT C | 420 | 123 |

| AChE | Rev | TTC ATA GAT ACC AAC ACG GTT CCC | 542 | |

| APP | For | GCA GAA TGG AAA ATG GGA GTC AG | 278 | 199 |

| APP | Rev | AAT CAC GAT GTG GGT GTG CGT C | 476 | |

| Tau | For | CGC CAG GAG TTT GAC ACA ATG | 244 | 65 |

| Tau | Rev | CCT TCT TGG TCT TGG AGC ATA GTG | 308 | |

| SPTLC-1 | For | CTAACCTTGGGCAAATCGAA | 2581 | 96 |

| SPTLC-1 | Rev | TGAGCAGGGAGAAGGGACTA | 2676 | |

| SPTLC-2 | For | GGA CAG TGT GTG GCC TTT CT | 1823 | 50 |

| SPTLC-2 | Rev | TCA CTG AAG TGT GGC TCC TG | 1872 | |

| CERS-1 | For | TGC GTG AAC TGG AAG ACT TG | 947 | 98 |

| CERS-1 | Rev | CTT CAC CAG GCC ATT CCT TA | 1044 | |

| CERS-2 | For | CTC TGC TTC TCC TGG TTT GC | 698 | 82 |

| CERS-2 | Rev | CCA GCA GGT AGT CGG AAG AG | 779 | |

| CERS-4 | For | CGA GGC AGT TTC TGA AGG TC | 1240 | 72 |

| CERS-4 | Rev | CCA TTG GTA ATG GCT GCT CT | 1311 | |

| CERS-5 | For | GAC AGT CCC ATC CTC TGC AT | 1254 | 92 |

| CERS-5 | Rev | GAG GTT GTT CGT GTG TGT GG | 1345 | |

| UGCG | For | GAT GCT TGC TGT TCA CTC CA | 2682 | 67 |

| UGCG | Rev | GCT GAG ATG GAA GCC ATA GG | 2748 | |

| SMPD-1 | For | CAG TTC TTT GGC CAC ACT CA | 1443 | 65 |

| SMPD-1 | Rev | CGG CTC AGA GTT TCC TCA TC | 1507 | |

| SMPD-3 | For | TCT GCT GCC AAT GTT GTC TC | 2704 | 98 |

| SMPD-3 | Rev | CCG AGC AAG GAG TCT AGG TG | 2801 |

Abbreviations: IGF = insulin-like growth factor; IRS = insulin receptor substrate; MAG = myelin associated glycoprotein; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; AIF = allograft inhibitory factor; IL = interleukin; TNF = tumor necrosis factor; ChAT = choline acetyltransferase; AChE = acetylcholinesterase; APP = amyloid precursor protein; SPTLC = serine palmitoyl transferase; CERS = ceramide synthase; UGCG = UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferae; SMPD = sphingomyelinase; bp = base pair.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA)

Tissue homogenates were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, as previously described [32]. Direct ELISAs were performed in 96-well plates (Nunc, Rochester, NY) as described [37]. In brief, proteins (40 ng/100 μl) adsorbed to well bottoms by overnight incubation at 4°C were blocked for 3 hours with 3% BSA in Tris buffered saline (TBS), then incubated with primary antibody (0.01–0.1 μg/ml) for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10000; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and Amplex Red soluble fluorophore (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) [37]. Amplex Red fluorescence was measured (Ex 579/Em 595) in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Binding specificity was determined from parallel negative control incubations with non-relevant antibodies or with the primary or secondary antibody omitted. Levels of immunoreactivity were normalized to protein content in parallel wells as determined with the NanoOrange Protein Quantification Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Receptor binding assays

Competitive equilibrium binding studies were used to examine effects of NDEA exposure on insulin and IGF-I receptor binding in liver, cerebellum, and temporal lobe, i.e., assess liver and brain insulin/IGF resistance as previously described [38]. To measure total binding, NP-40 lysis buffer homogenates were incubated with 50 nCi/ml of [125I] (2000 Ci/mmol; 50 pM) insulin or IGF-I in binding buffer (100 mM HEP-ES, pH 8.0, 118 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 8.8 mM dextrose, 5 mM KCl, 1% bovine serum albumin). To measure non-specific binding, identical reactions were prepared with the addition of 0.1 μM unlabeled (cold) ligand. After 16-hours incubation at 4°C, reactions were vacuum harvested (Corning, Lowell, MA) onto 96-well GF/C filter plates that had been pre-soaked in 0.33% polyethyleneimine. The filters were vacuum washed with 50 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4, 500 mM Na-Cl, and 0.1% BSA. [125I]-bound insulin or IGF-I was measured in a TopCount (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA). Specific binding was calculated by subtracting non-specifically bound from the total bound isotope [32].

Sources of reagents

Human recombinant [125I]-Insulin and IGF-I were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Boston, MA). Unlabeled human insulin and recombinant IGF-I were obtained from Bachem (Torrance, CA). QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Mix was obtained from (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA). Rabbit, mouse, or goat generated monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies to ubiquitin, tau, phospho-tau, GFAP, HNE, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), amyloid-β protein precursor-amyloid-β peptide (AβPP-Aβ), and β-actin, were purchased from Chemicon (Tecumsula, CA), CalBiochem (Carlsbad, CA), or Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). All other fine chemicals were purchased from either CalBiochem (Carlsbad, CA) or Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical analysis

Data depicted in the graphs and tables represent the means ± S.E.M. for each group, with 8–10 samples included per group. Inter-group comparisons were made using Student t-tests or the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and either the Tukey-Kramer or Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test for significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Computer software generated significant P-values are shown over the graphs.

RESULTS

Rotarod tests performance

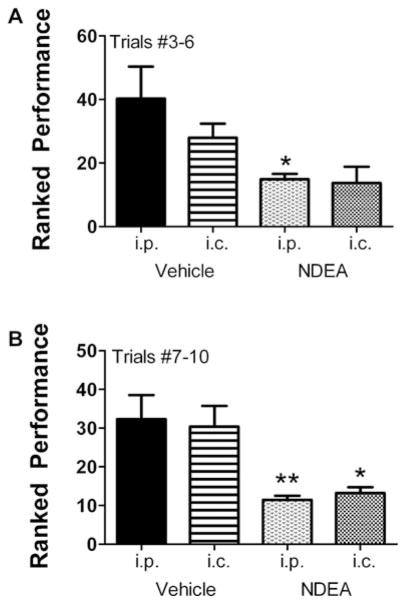

The rotarod test is used to assess sensorimotor coordination and provides a highly sensitive index of damage to the cerebellum [39]. Rotarod test results were analyzed by grouping performance for Trials 3–6 and Trials 7–10, in which the rotation speeds were incremented from 5 to 7 rpm, and 8 to 10 rpm, respectively. Results from Trials 1 and 2 were not included since they were regarded as part of the training. The mean ± S.E.M. latency to fall periods were calculated separately for the i.c. and i.p. vehicle- or NDEA-treated rats. For the earlier (lower speed) set of trials, the NDEA-treated rats exhibited lower mean latencies to fall relative to the control groups, but the differences from corresponding controls were significant only for rats injected with NDEA i.p., because the S.E.M. for the i.c.-NDEA-treated group data was high (Fig. 1A). For the higher speed, i.e., later trials, the mean latencies to fall were significantly shorter in both the i.p. and i.c. NDEA-treated groups relative to corresponding controls (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

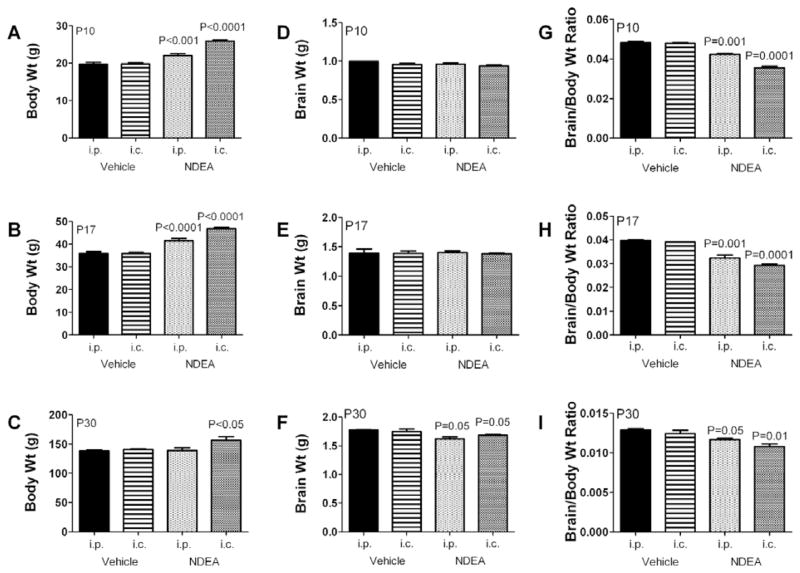

NDEA increases body mass and reduces brain weight. Long Evans rats were treated with either 1–10 μg intra-cerebral (i.c.) or 3–20 μg alternate day intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of NDEA or vehicle, from postnatal day 3 (P3). The mean body weight on P3 was 10 g. Graphs depict the means ± S.E.M. for body weight [A,D,G], brain weight [B,E,H], and calculated brain/body weight ratio [C,F,I] obtained on P10, P17, or P30. We sacrificed 6 or 7 rats per group to obtain brain weights on P10 and P17. Results were analyzed statistically using repeated measures ANOVA and the post-hoc Dunn’s test. Significant P-values relative to i.p. vehicle-injected controls are indicated over the bars.

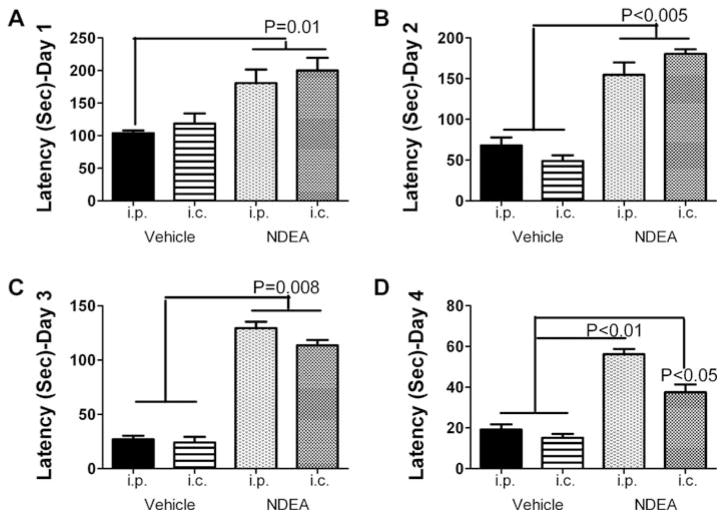

Morris water maze performance

The Morris water maze is a behavioral test that assesses spatial memory and detects degeneration or injury in the hippocampus and temporal cortex [40–42]. NDEA treatment by either the i.c. or i.p. route significantly impaired performance on the Morris water maze test. Although the mean (area under curve) latencies for locating and landing on either the platform declined over the time period of testing in all groups, the mean latencies were consistently higher in rats treated with NDEA versus vehicle on each of the test days (Fig. 2). We were surprised to find that rats injected with NDEA i.c. were somewhat less impaired than those injected by the i.p. route, particularly on Day 4 of testing (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

NDEA treatment impairs motor learning. Long Evans rats treated with NDEA or vehicle by i.p. or i.c. injection (see Figure Legend 1; N = 12/group), were trained to remain balanced on the rotating Rotamex-5 apparatus (Columbus Instruments) at 5 rpm. On P16, rats were administered 10 trials at incremental speeds from 5 to 10 rpm, with 10 minutes rest between each trial. However, trials were stopped after 30 seconds to avoid exercise fatigue. The latency to fall was automatically detected and recorded with photocells placed over the rod. Mean ± S.E.M. of results from [A] Trials #3–6 (5–7 rpm) and [B] Trials #7-10 (8–10 rpm) are depicted graphically. Data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test for significance (*P < 0.01; * * P < 0.001 relative to i.p. vehicle treated control group).

Effects of NDEA treatment on body and brain weight

Body and brain weights among i.p. and i.c. vehicle-or NDEA-treated rats were measured at 3 different time points: postnatal day (P) 10, P17, and P30 (Fig. 3). In addition, we calculated mean brain/body weight ratios to further illustrate the long-term impact of the early life NDEA exposure. Mean body weights were similar prior to treatment (data not shown). On P10 and P17, the mean body weights were significantly higher in rats injected with NDEA, either i.p. or i.c., relative to vehicle (Figs 3A–3B). On P30, the i.c. NDEA treated rats still had a significantly increased mean body weight, but the i.p. NDEA treated rats had a “normalized” mean body weight relative to control (Fig. 3C). Mean brain weights were similar among all groups on P10 and P17, but they were significantly reduced at P30 in both i.p. and i.c. NDEA-treated relative to control groups (Figs 3D–3F). The calculated mean brain/body weight ratios were significantly lower in i.p. and i.c. NDEA-treated relative to controls at P10, P17, and P30 (Figs 3G–3I). Note the significantly reduced brain/body weight ratios at P30 occurred vis-à-vis nearly normalized mean body weight in the NDEA-treated groups. Because the effects of i.c. and i.p. NDEA were so similar, we simplified the subsequent data presentation by focusing on the effects of i.p. NDEA treatment. In addition to minimizing potentially confounding effects of the i.c. injections, the i.p. route of NDEA administration was deemed more relevant to human exposures because ingested NDEA reaches target organs, including brain, liver, kidney, lung and spleen via the circulation [43], and drugs or toxins delivered i.p. eventually enter the blood supply [44].

Fig. 3.

NDEA treatment impairs spatial learning and memory. Long Evans rats treated with vehicle or NDEA by i.p. or i.c. injection (N = 12/group), were subjected to Morris water maze testing on 4 consecutive days beginning at age P24. On Day 1 of testing, the platform was visible, but on Days 2–4, the platform was submerged, and on Days 3–4, the water entry quadrant was randomized. On each testing day, rats were given 3 trials, with a maximum of 120 seconds allowed to land on the platform, beyond which they were guided. Area under curve (AUC) was calculated for each series of trials each day. Graphs depict the mean ± S.E.M. AUC latencies for each group on each day of testing. Data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA and Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test for significance. Significant P-values are indicated over the bars.

NDEA-induced T2DM and NASH (Tables 2 and 3)

Table 2.

NDEA Effects on Serum Glucose, Insulin, and Lipid

| Assay* | Control (N = 10) | NDEA (N = 11) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 103.3 ± 1.45 | 128.3 ± 3.69 | < 0.0001 |

| Insulin (μIU/ml) | 5.21 ± 2.02 | 28.42 ± 6.11 | 0.001 |

| Nile Red (FLU) | 254.5 ± 15.0 | 257.8 ± 4.7 | NS |

| Triglycerides | 0.403 ± 0.05 | 0.437 ± 0.03 | NS |

| Free Fatty Acids | 0.150 ± 0.002 | 0.114 ± 0.011 | NS |

Nile red and cholesterol assays were measured in fluorescence light units (FLU). Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using Student T-tests.

Table 3.

NDEA Effects on Hepatic Lipid Content and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine mRNA Expression

| Assay* | Control (N = 8) | NDEA (N = 8) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nile Red (FLU) | 180.0 ± 17.1 | 238.5 ± 20.70 | 0.013 |

| Cholesterol (FLU) | 1533.2 ± 52.40 | 1799.9 ± 115.7 | 0.016 |

| Trig/μg Protein | 46.4 ± 80.3 | 69.7 ± 4.40 | 0.007 |

| Cytokine** | |||

| IL-1β | 0.084 ± 0.011 | 0.118 ± 0.010 | 0.048 |

| IL-6 | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.008 ± 0.002 | NS |

| TNF-α | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | NS |

Nile red and cholesterol assays were measured in fluorescence light units (FLU); Trig = triglyceride.

IL = Interleukin; TNF = tumor necrosis factor; All mRNA values normalized to 18s rRNA. Results show mean ± S.E.M. relative mRNA levels (×10−6). Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using Student T-tests.

In P30 rats, the mean fasting blood glucose and serum insulin levels were significantly higher in the i.p. NDEA treated relative to vehicle-treated controls (Table 2). However, NDEA treatment did not cause hyper-lipidemia, as demonstrated with the Nile Red assay for neutral lipids, and assays of serum triglyceride and free fatty acids (Table 2). In contrast, the livers of NDEA-treated rats had significantly increased total lipid (Nile Red assay), cholesterol, and triglyceride (calculated with respect to protein concentration or tissue weight) content relative to control livers (Table 3). Since hepatic steatosis can be associated with inflammation and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [45], we also measured interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in liver by qRT-PCR. Those studies revealed significantly higher mean levels of IL-1β mRNA in NDEA-treated relative to control livers, but similar levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in both groups (Table 3).

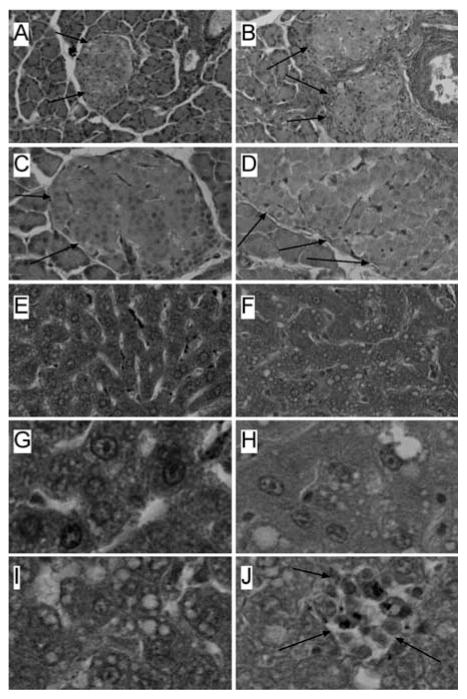

NDEA treatment causes pancreatic islet hypertrophy and NASH

Histopathologic studies of pancreas and liver were performed using P30 rats. The pancreases from NDEA-treated rats had conspicuously enlarged islets (Figs 4A, 4C) relative to controls (Figs 4B, 4D). Correspondingly, image analysis using Image Pro Plus 3 software (EPIX, Inc. Buffalo Grove, IL), demonstrated a significantly greater mean diameter of pancreatic islets in NDEA-treated (284.2 ± 11.6 μm) relative to control (207.9 ± 10.7 μm) rats (P = 0.0001). The mean diameter of the control pancreatic islets is comparable to the findings in a previous report [46]. We did not detect abnormalities in exocrine pancreatic tissue, or increased inflammation or necrosis associated with islet hypertrophy in NDEA-treated rats.

Fig. 4.

NDEA-induced pancreatic islet hypertrophy and NASH. Long Evans rats were treated by i.p. injection of NDEA or vehicle (see details in legend to Fig. 1), and then sacrificed on P30. Pancreas and liver tissue samples were immersion fixed and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections were stained with H&E. Photomicrographs depict (A, C) Control and (B, D) NDEA-exposed pancreases at low (original-x100; A, B) and high (original-x400; C, D) magnifications. Note hypertrophied islets in pancreases from NDEA-treated relative to control rats (arrows point to islets). Image analysis confirmed that the mean diameter of islets in NDEA-treated rats was significantly greater than control (P < 0.001). (E, G) Control livers displayed regular cord-like architecture with uniform nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and no evidence of steatosis, inflammation, or necrosis. In contrast, (F, H, I, J) NDEA-exposed livers exhibited loss of hepatic cord architecture, (F, H, I) micro-steatosis with clusters of cytoplasmic vacuoles, and (J) scattered foci of lymphomononuclear cell inflammation and necrosis. (Colours are visible in the electronic version of the article at www.iospress.nl)

Control livers displayed a regular cord-like architecture with minimal or no evidence of inflammation, steatosis, or apoptosis (Figs 4E, 4G). In contrast, livers of NDEA-treated rats exhibited micro-steatosis, disorganization of the hepatic cord architecture, scattered foci of inflammation composed of lymphomononuclear cells, and small foci of necrosis, or individual cell apoptosis (Figs 4F, 4H-4J). These features correspond with the hepatic pathology associated with STZ treatment in rats [47–49], and are highly consistent with NASH [1, 12,50]. None of the livers from NDEA-treated rats showed evidence of malignant transformation, i.e., tumors, nodules, or foci of anaplasia.

Neuropathology of NDEA exposure

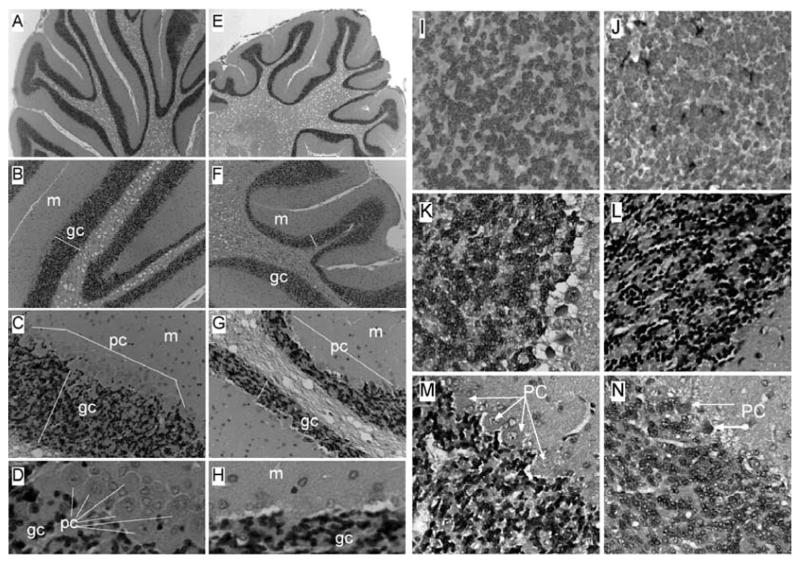

H&E stained sections of control cerebella revealed relatively long, thin, and uniform folia with well-populated internal granule and Purkinje cell cortical layers (Figs 5A–5D). In contrast, cerebella from NDEA-treated rats had blunted, shallow folia with conspicuous irregularities in thickness and cellularity of the internal granule and Purkinje cell layers. Broad stretches of neuronal loss were evident in the Purkinje cell layer (Figs 5E–5H). The prominent and somewhat selective NDEA-mediated degeneration of the cerebellar cortex rendered the white matter appearance to be excessive or expanded (Figs 5E–5F). Adjacent histological sections were immunostained to detect GFAP (Figs 5I–5J), HNE (Figs 5K–5L), or ubiquitin (Figs 5M–5N) as indices of gliosis, lipid peroxidation/oxidative stress, and cellular degeneration, respectively. Corresponding with the histopathologic studies, NDEA treatment resulted in increased GFAP and HNE immunoreactivity in the granule cell layer, and increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity in the Purkinje cell layer relative to control cerebella (Figs 5I–5N).

Fig. 5.

Cerebellar degeneration in NDEA-treated rats. Long Evans rats were injected i.p. with vehicle or NDEA (N = 12/group) beginning on P3, and sacrificed on P30. Brains were preserved in Histofix and paraffin-embedded sections (8 microns) were stained with H&E and examined by light microscopy. Panels depict increasing magnification images of cerebella from (A–D) vehicle- or (E–H) NDEA-treated rats. Note long, slender folia with thin white matter cores, and well-populated granule cell (gc) and Purkinje cell (pc) layers in control cerebella, compared with the (E) shorter, blunted folia with broad white matter cores, thinner, less populated gc and pc layers, (G, H) broad zones of pc absence, and a thinner molecular layer (m) in NDEA-treated rats. (I–N) Histological sections were immunostained to detect (I, J) glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), (K, L) 4-hydroxy-2-nonenol (HNE), or (M, N) ubiquitin. Immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex reagents, and DAB as the chromogen (brown precipitate). Sections were counterstained lightly with Hematoxylin. Panels depict cerebellar cortex of (I, K, M) vehicle- or (J, L, N) NDEA-treated rats. In NDEA-exposed rats, increased GFAP immunoreactivity was detected in scattered cells within the granule cell layer, abundant HNE immunoreactivity was observed throughout the granule cell layer, as well as the molecular layer (not shown), and increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity was observed in Purkinje cells. (Colours are visible in the electronic version of the article at www.iospress.nl)

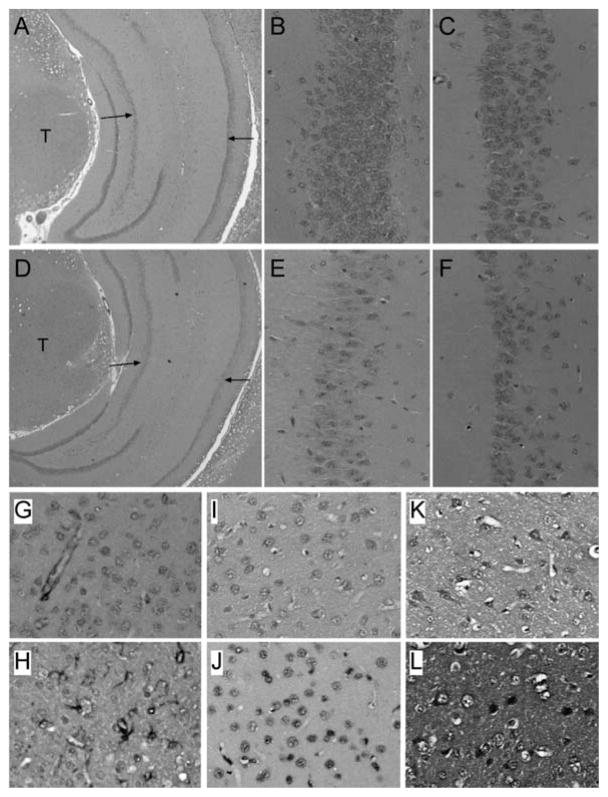

In the temporal lobe, the most striking effects of NDEA exposure were observed in the hippocampal formation. H&E stained sections demonstrated that all four segments of Ammon’s horn (CA1-CA4) of the hippocampal formation were richly populated by neurons in control brains. In contrast, in NDEA-exposed rats, neuronal loss was conspicuously evident in CA1-CA3 (Figs 6A–6F). NDEA-mediated cell loss was not overtly evident in the temporal cortex. However, immunohistochemical staining demonstrated prominently increased levels of GFAP, HNE, and ubiquitin in NDEA-treated relative to control temporal lobes (Figs 6G–6L). GFAP immunoreactivity was localized in the cytoplasm and coarse fibrils of glia, whereas HNE and ubiquitin immunoreactivities were detected in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and/or fine neuropil fibers of glia (small oval vesicular or round hyperchromatic nuclei corresponding to astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, respectively) and neurons (large nucleolated cortical cells) in NDEA-exposed brains.

Fig. 6.

Hippocampus and temporal lobe degeneration following NDEA treatment. Long Evans rats were injected i.p. with vehicle or NDEA (N = 12/group) beginning on P3, and then sacrificed on P30 to harvest brains. Brains were preserved in Histofix, embedded in paraffin, and histological sections (8 microns) were (A–F) stained with H&E, or immunostained to detect (G, H) GFAP, (I, J) HNE, or (K, L) ubiquitin (see Methods and Figure 5 legend). Panels D–F demonstrate reduced cellularity in Ammon’s horn (arrows) of the hippocampus in NDEA-exposed rats relative to control (A–C). Note conspicuously reduced neuronal densities in both the (E) CA3 and (F) CA1 regions of the hippocampus of NDEA-treated relative to (B, C) corresponding regions of control hippocampus. T = thalamus; left arrow = CA3, right arrow = CA1. Panels G–L depict temporal cortex of (G, I, K) vehicle- or (H, J, L) NDEA-treated rats. In NDEA-exposed rats, increased GFAP immunoreactivity was detected in (H) small clusters of activated astrocytes within the cortex versus (G) confinement to the perivascular regions in controls. Increased (I, J) HNE and (K, L) ubiquitin immunoreactivity were localized to nuclei and cytoplasm of neurons (large cells with nucleoli), as well as smaller non-neuronal cells in (J, L) NDEA-treated relative to (I, K) control. Ubiquitin immunoreactivity was also increased in neuropil fibers of (L) NDEA-treated relative to (K) control temporal cortex. (Colours are visible in the electronic version of the article at www.iospress.nl)

NDEA-treatment causes sustained abnormalities in gene expression in brain

We used qRT-PCR analysis and ELISAs to quantify long-term effects of i.p. NDEA treatment on mR-NA and protein expression in brain. The qRT-PCR studies demonstrated that NDEA treatment significantly reduced the mean mRNA levels of myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG-1; P = 0.026), GFAP, and ChAT (P < 0.0001) in the cerebellum. NDEA exposure also marginally impaired cerebellar Hu neuronal gene expression (P = 0.058), but had no significant effect on the levels of allograft inhibitory factor-1 (AIF-1; corresponding to activated microglia), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), or 18S rRNA (Table 4A). With regard to the temporal lobe, NDEA exposure significantly reduced the mean mRNA levels of MAG-1 (P = 0.045) and ChAT (P = 0.0006), and increased the mean mRNA levels of GFAP (P = 0.025) and AChE (P = 0.0016). However, it did not significantly alter temporal lobe RNA levels of Hu, AIF-1, or 18S (Table 4B).

Table 4A.

NDEA-Mediated Neurodegeneration-Cerebellum qRT-PCR

| mRNA* | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HU | 1.004 ± 0.082 | 0.807 ± 0.056 | 0.0576 |

| MAG-1 | 7.775 ± 0.559 | 6.023 ± 0.498 | 0.0261 |

| GFAP | 0.075 ± 0.006 | 0.035 ± 0.004 | < 0.0001 |

| AIF-1 | 0.248 ± 0.017 | 0.247 ± 0.019 | |

| ChAT | 3.480 ± 0.337 | 1.545 ± 0.130 | < 0.0001 |

| AChE | 3.712 ± 0.393 | 3.828 ± 0.302 | |

| 18S | 2.346 ± 0.059 | 2.303 ± 0.066 |

Table 4B.

NDEA-Mediated Neurodegeneration-Temporal Lobe qRT-PCR

| mRNA* | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HU | 0.641 ± 0.044 | 0.629 ± 0.051 | |

| MAG-1 | 0.026 ± 0.005 | 0.012 ± 0.005 | 0.045 |

| GFAP | 0.263 ± 0.016 | 0.453 ± 0.042 | 0.025 |

| AIF-1 | 0.105 ± 0.011 | 0.092 ± 0.008 | |

| ChAT | 1.279 ± 0.083 | 0.869 ± 0.066 | 0.0006 |

| AChE | 0.992 ± 0.123 | 1.530 ± 0.130 | 0.0016 |

| 18S | 2.85 ± 0.15 | 2.689 ± 0.089 |

ELISA studies of cerebellar tissue demonstrated that NDEA exposure significantly increased the mean levels of tau (P = 00006), phospho-tau (P = 0.0003), and AβPP-Aβ (P = 0.0001), and reduced the mean levels of ChAT (P = 0.026). In addition, GFAP immunoreactivity was marginally increased, while AChE and β-actin immunoreactivity were unaffected in cerebella of NDEA-exposed rats (Table 4C). With regard to the temporal lobe, ELISA studies revealed significantly higher mean levels of GFAP (P < 0.0001), AβPP-Aβ (P = 0.018), and AChE (P = 0.0008), reduced levels of ChAT (P = 0.04), but no significant alterations in the levels of tau, phospho-tau, or β-actin in the NDEA-treated group (Table 4D).

Table 4C.

NDEA-Mediated Neurodegeneration-Cerebellum ELISA

| Protein** | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFAP | 1741.47 ± 89.93 | 1987.02 ± 176.99 | 0.11 |

| Tau | 2147.51 ± 83.64 | 2748.15 ± 136.76 | 0.0006 |

| p-tau | 2402.24 ± 259.55 | 4470.15 ± 436.07 | 0.0003 |

| AβPP-Aβ | 2329.94 ± 237.59 | 4490.18 ± 429.37 | 0.0001 |

| ChAT | 4966.14 ± 573.62 | 3684.24 ± 244.35 | 0.0259 |

| AChE | 10386.97 ± 745.20 | 10624.12 ± 478.27 | |

| β–ACTIN | 1626.31 ± 42.18 | 1580.41 ± 55.41 |

Table 4D.

NDEA-Mediated Neurodegeneration-Temporal Lobe ELISA

| Protein** | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFAP | 997.53 ± 11.45 | 1124.10 ± 15.57 | < 0.0001 |

| Tau | 970.20 ± 13.48 | 976.27 ± 8.20 | |

| p-tau | 546.65 ± 3.11 | 544.55 ± 2.28 | |

| AβPP-Aβ | 576.54 ± 3.38 | 667.90 ± 2.01 | 0.0178 |

| ChAT | 986.23 ± 8.54 | 925.82 ± 10.77 | 0.0440 |

| AChE | 1027.67 ± 15.46 | 1101.42 ± 14.74 | 0.0008 |

| β–ACTIN | 1626.31 ± 42.18 | 1580.41 ± 55.41 |

mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR with values normalized to 18s rRNA (×106). Results show mean ± S.E.M. for each group.

Immunoreactivity was measured by direct binding ELISA with levels normalized to protein content in the wells. Values shown are in arbitrary fluorescence light units (FLU). Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using T-test analyses. See abbreviations list in Table 1 legend.

NDEA exposure impairs insulin and IGF signaling mechanisms and causes hepatic and brain insulin/IGF resistance (Table 5)

Table 5A.

NDEA Treatment Alters Expression of Genes Mediating Hepatic Insulin and IGF Signaling

| mRNA* | Control (N = 8)* | NDEA (N = 7)* | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor | 0.425 ± 0.069 | 0.978 ± 0.058 | 0.001 |

| IGF-I Receptor | 0.032 ± 0.005 | 0.043 ± 0.007 | |

| IGF-II Receptor | 0.183 ± 0.058 | 0.201 ± 0.023 | |

| Insulin | 0.011 ± 0.003 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.03 |

| IGF-I | 30.91 ± 3.817 | 34.65 ± 3.715 | |

| IGF-II | 0.073 ± 0.015 | 0.141 ± 0.015 | 0.003 |

| IRS-1 | 0.281 ± 0.050 | 0.507 ± 0.061 | 0.005 |

| IRS-2 | 0.147 ± 0.028 | 0.186 ± 0.022 | |

| IRS-4 | 0.002 ± 0.0004 | 0.004 ± 0.0004 | 0.01 |

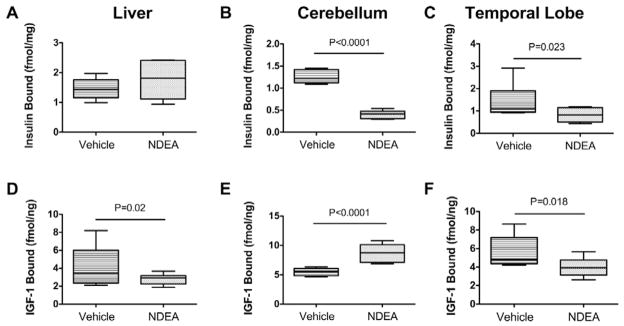

qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that NDEA exposure significantly increased insulin receptor (P = 0.001), IGF-II (P = 0.003), IRS-1 (P = 0.005), and IRS-4 (P = 0.01), and decreased insulin gene (P = 0.03) expression in liver (Table 5A). In addition, IGF-I receptor, IGF-II receptor, IGF-I, and IRS-2 were all marginally higher in NDEA-treated relative to control livers, but those inter-group differences did not reach statistical significance. With regard to the cerebellum, NDEA treatment resulted in significantly reduced mR-NA levels of insulin receptor (P = 0.004), IGF-I receptor (P = 0.02), and insulin (P = 0.0004), and increased levels of IGF-II receptor (P < 0.0001), IRS-1 (P = 0.001), IRS-2 (P = 0.003), and IRS-4 (P < 0.0001) (Table 5B). With regard to the temporal lobe, NDEA treatment significantly reduced insulin receptor (P = 0.0003), IGF-II receptor (P = 0.001), IGF-I (P = 0.001), and IRS-2 (P = 0.0003), and increased IRS-1 (P < 0.0001) expression levels. Finally, competitive equilibrium binding assays demonstrated that NDEA treatment significantly reduced insulin receptor binding in the temporal lobe and cerebellum, and IGF-I binding in liver and temporal lobe (Fig. 7). In contrast, IGF-I receptor binding was significantly higher in the NDEA-exposed relative to control cerebella (Fig. 7E). Since these impairments in ligand-receptor binding were not consistently correlated with reduced expression of the corresponding receptors and/or trophic factors, additional mechanisms of insulin/IGF resistance had to be explored.

Table 5B.

NDEA Treatment Alters Expression of Genes Mediating Cerebellar Insulin and IGF Signaling

| mRNA* | Control (N = 8)* | NDEA (N = 16)* | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor | 8.706 ± 0.957 | 5.065 ± 0.868 | 0.004 |

| IGF-I Receptor | 5.827 ± 0.479 | 3.890 ± 0.771 | 0.02 |

| IGF-II Receptor | 2.692 ± 0.315 | 8.718 ± 1.180 | < 0.0001 |

| Insulin | 0.133 ± 0.013 | 0.071 ± 0.009 | 0.0004 |

| IGF-I | 0.581 ± 0.068 | 0.519 ± 0.084 | |

| IGF-II | 37.37 ± 11.37 | 38.69 ± 9.63 | |

| IRS-1 | 1.415 ± 0.223 | 3.271 ± 0.498 | 0.001 |

| IRS-2 | 2.045 ± 0.203 | 4.095 ± 0.669 | 0.003 |

| IRS-4 | 0.095 ± 0.014 | 0.274 ± 0.036 | < 0.0001 |

Fig. 7.

NDEA exposure leads to impaired insulin and IGF receptor binding in liver and/or brain. Competitive equilibrium binding studies were performed with 8 samples each of liver, cerebellum, or temporal lobe protein homogenates from i.p. vehicle- or NDEA-treated rats. Reactions were incubated with 50 nCi/ml of [125I] (2000 Ci/mmol; 50 pM) insulin or IGF-I in binding buffer in the presence or absence of 0.1 μM unlabeled ligand. Radiolabeled bound ligand was harvested onto 96-well GF/C filter plates and measured in a TopCount. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting non-specifically bound from the total bound isotope. Box plots depict mean ± S.D. of specific binding for (A–C) insulin and (D–F) IGF-I measured in (A, D) liver, (B, E) cerebellum, and (C, F) temporal lobe. Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using Student T-Tests. Significant P-values are shown within the panels.

NDEA-mediated increases in pro-ceramide gene expression

We investigated the potential role of increased pro-ceramide gene expression as a mediator of liver and brain insulin/IGF resistance because ceramides: 1) can be generated in liver and brain [51–54]; 2) cause insulin resistance [54]; 3) are cytotoxic [54]; 4) increase in the CNS with various dementia-associated diseases, including AD [51,55–57]; and 5) are lipid soluble and therefore likely to readily cross the blood-brain barrier. Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that increased ceramide gene expression in liver correlates with neurodegeneration associated with obesity, T2DM, and NASH [31], and that in vitro ceramide exposure causes neurodegeneration [30]. We measured mRNA levels of several pro-ceramide genes including ceramide synthases (CerS), UDP glucose ceramide glycosyltransferase (UGCG), serine palmitoyltransferase (SPTLC), and sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase (SM-PD) because of their relevance to neurodegeneration and/or NASH [30,31]. Those studies demonstrated that NDEA exposure significantly increased the mean mR-NA levels of CerS4 (P = 0.019), UGCG (P < 0.0001), SMPD1 (P = 0.02), and SPTLC1 (P = 0.002) in liver, and CerS2 (P = 0.013) and SMPD3 (P = 0.023) in the temporal lobe (Table 6).

Table 6A.

NDEA Activation of Ceramide Genes in Liver

| mRNA* | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CerS2 | 17.93 ± 1.88 | 21.9 ± 1.86 | |

| CerS4 | 0.09 ± 0.013 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | 0.019 |

| CerS5 | ND | ND | |

| UGCG | 1.71 ± 0.136 | 3.16 ± 0.24 | < 0.0001 |

| SMPD1 | 7.16 ± 0.95 | 10.6 ± 1.24 | 0.02 |

| SMPD3 | ND | ND | |

| SPTLC1 | 0.32 ± 0.028 | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 0.002 |

| SPTLC2 | ND | ND |

DISCUSSION

Herein, we examined the degree to which limited NDEA exposure causes the triad of major human insulin-resistance diseases, namely, T2DM, NASH, and AD, whose prevalence rates have literally soared over the past several decades. Our over-arching hypothesis is that the epidemiological trends corresponding to these diseases fit exposure rather than genetic models, and that shifts in lifestyles and economics have increased human exposures to agents that cause organ-system degeneration with insulin resistance. The pivotal point enabling us to narrow our considerations with respect to potential pathogenic agents was the fact that ample existing experimental evidence showed that STZ, a nitrosamine-related chemical, is mutagenic in high doses [17], but causes insulin-resistance disease at lower doses and limited durations of exposure [18–25, 58]. Since STZ is not generally available to consumers, we considered the possibility that nitrosamines and related compounds that do exist in our environment, serve as constant sources of human exposure, and thereby account for the observed changes in the prevalence rates of insulin resistance diseases.

The in vivo model of NDEA exposure was designed to mimic the STZ exposure model that produced both T2DM and neurodegeneration [22,25]. Since the STZ causes central nervous system (CNS) neuronal injury, degeneration, and death in structures that express high levels of insulin and IGF receptors, e.g., cerebellum and temporal lobe [33,34], we characterized the effects of NDEA treatment on the structural and functional integrity of these brain regions, and the long-term neurobehavioral consequences of the abnormalities produced. Although one could argue that some of the neuropathology and CNS molecular and biochemical abnormalities detected in the STZ and NDEA models are developmental in nature, in fact the abnormalities are progressive [59], post-mitotic neurons in the temporal lobe are significantly affected, and at least with respect to STZ, similar neurodegenerative effects have been produced in adult rats [60–65].

The knowledge that: 1) human nitrosamine exposures occur through many sources including, consumption of processed and preserved foods, smoking tobacco (direct or second hand), use of nitrate-containing fertilizers, and manufacturing; and 2) nitrosamines are mutagenic and cause tissue injury in manners similar to STZ [17,19,27,29], begged the question as to whether nitrosamines have pathogenic roles in our insulin resistance diseases epidemic. To test this hypothesis, we generated an in vivo model in which rat pups were treated with NDEA at doses that were 5-fold to 500-fold lower than the cumulative doses used to produce cancer in experimental animals [66–69]. Although experiments were conducted by administering NDEA by either i.c. or i.p. injection, the effects were similar. Nonetheless, we focused on results obtained with i.p. injected rats to simplify the data presentation, and also because the model is more relevant to the types of exposures humans endure. The use of young rats enabled us to examine effects of NDEA exposure on later motor and cognitive functions, and for comparison with previous observations in the i.c.-STZ model [34].

NDEA treatment significantly increased body weight relative to age-matched controls during the first 3 weeks of life. Although their body weights had nearly normalized by P30 (sacrifice), the NDEA treated rats still had T2DM, characterized by fasting hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and pancreatic islet hypertrophy[70, 71]. Moreover, the livers of NDEA treated rats displayed steatohepatitis with hepatocellular disarray and foci of necrosis or apoptosis by histopathological examination, increased lipid content, including triglycerides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids by biochemical measurements, impaired binding to the insulin receptor by competitive equilibrium binding assays, and increased IL-1β and reduced insulin mRNA expression by qRT-PCR analysis. This constellation of steatohepatitis with hepatic insulin resistance and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine expression fulfills criteria for NASH. Since the insulin receptor and IRS molecules relay insulin-stimulated signals, the associated upregulation of these genes in NDEA-exposed livers could represent a compensatory response to impaired insulin signaling.

The NDEA treatments caused significant cognitive and motor deficits with structural, biochemical, and molecular abnormalities in the brain. Impairments in rotarod performance were associated with cerebellar hypoplasia and/or degeneration with evidence of persistent cell loss, gliosis, lipid peroxidation and degeneration (ubiquitin immunoreactivity) in the granule and Purkinje cell layers of cortex. The qRT-PCR analyses demonstrated reduced expression of genes corresponding to glial and neuronal elements. ELISA studies demonstrated that NDEA treatment chronically increased the levels of tau, phospho-tau and AβPP-Aβ. Both qRT-PCR and ELISA studies provided evidence that NDEA exposure causes sustained disturbances in cholinergic neurotransmitter homeostasis characterized by reduced levels of ChAT and increased levels of AChE. Further studies demonstrated that NDEA treatment significantly reduced insulin, IGF-I, and IGF-II receptor binding, and insulin, insulin receptor, and IGF-I receptor gene expression in the cerebellum.

NDEA treatment also impaired spatial learning and memory as demonstrated by Morris water maze testing. Correspondingly, the temporal lobe had striking histopathological abnormalities in the hippocampal formation where neuronal loss was conspicuous. In addition, immunohistochemical staining revealed increased gliosis, lipid peroxidation, and ubiquitin immunoreactivity in the temporal neocortex, similar to the findings in the cerebellar cortex. The qRT-PCR analyses demonstrated reduced expression of MAG-1 and ChAT, but increased levels of GFAP and AChE, indicating disturbances in oligodendroglial and cholinergic functions. ELISA results revealed increased GFAP, AβPP-Aβ, and AChE, and reduced ChAT immunoreactivity, confirming that NDEA-mediated neurodegeneration increases AβPP-Aβ immunoreactivity and disturbs cholinergic homeostasis, similar to the effects of i.c.-STZ [22,25,34]. Molecular and biochemical studies demonstrated NDEA-mediated inhibition of IGF-I, insulin receptor, and IGF-II receptor expression, and insulin and IGF-I receptor binding in the temporal lobe. Therefore, NDEA causes both insulin and IGF resistance manifested by decreased receptor and IRS gene expression and/or reduced receptor binding, similar to the effects of i.c.-STZ [22,25,34].

In essence, NDEA-induced neuro-cognitive deficits with neurodegeneration were associated with neuronal loss, persistent oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, increased levels of phospho-tau, GFAP, and AβPP-Aβ, impairments in cholinergic function, and CNS insulin/IGF resistance and/or deficiency. These abnormalities are quite similar to the effects of both i.c. STZ treatment in rats and sporadic AD neurodegeneration in humans [34]. NDEA-mediated neuronal loss, oligodendroglial dysfunction, and impairments in acetylcholine homeostasis were likely mediated by insulin/IGF resistance and attendant perturbations in downstream signaling since neuronal and oligodendroglial survival and function and ChAT expression are regulated by insulin/IGF signaling mechanisms [34]. The NDEA-mediated persistent oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and increased levels of phospho-tau and AβPP-Aβ, correspond with our recent in vitro experimental results where, neurons treated with NDEA had virtually the same responses, in addition to increased DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction [30]. The NDEA-associated increases in AβPP-Aβ may have been mediated by persistent oxidative stress, since previous studies showed that oxidative stress was sufficient to cause AβPP-Aβ formation and accumulation in neurons [72]. The absence of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in brains of NDEA-treated rats may represent a limitation or differential feature of this model relative to human disease, or else, those specific pathological lesions may require prolonged periods of observation, and possibly aging. Nonetheless, the biochemical and molecular assay results and associated impairments in neuro-cognitive function indicate that NDEA causes neurodegeneration with several features in common with AD [34], and equally important, the adverse CNS effects of NDEA exceed those arising secondary to obesity and T2DM [31,32].

The finding that both i.c. and i.p. administrations of NDEA caused neurodegeneration with neuro-cognitive dysfunction was not unexpected because NDMA and NDEA are lipid soluble [73,74], and therefore likely to cross the blood-brain barrier. Moreover, there is experimental evidence that after ingestion, NDEA and NDMA enter the circulation and can be detected in brain [43]. However, in exploratory studies, we observed greater severities of neuro-cognitive deficits and neurodegeneration following i.p. compared with i.c. administration of NDEA (data not shown). This suggests that secondary effects, possibly related to hepatic metabolism or hepatotoxicity contributed to NDEA-induced neurodegeneration. The fact that NDEA treatment also caused NASH, led us to investigate whether toxic lipids stemming from NASH-related injury could contribute to NDEA-mediated neurodegeneration. Since pro-ceramide genes are increased in experimental models of NASH [51,54,56,75], and ceramides cause neurodegeneration, pro-inflammatory cytokine activation, and insulin resistance [4,30,31, 51,54–56,76,77], we measured mRNA levels of pro-ceramide genes in liver and brain. Those studies revealed strikingly increased levels of several genes involved in ceramide generation via both biosynthesis and degradation pathways in liver, and relatively smaller but nonetheless statistically significant increases in pro-ceramide genes in brain. In addition, recent preliminary studies demonstrated that the i.p. NDEA treatments resulted in increased levels of ceramides in both liver and blood, as by dot blot analysis (data not shown). Since both NDEA and ceramides are lipid soluble and therefore likely to readily cross the blood-brain barrier, NDEA exposure could cause CNS insulin resistance and chronic injury by dual mechanisms: 1) causing direct neurotoxic injury; and 2) promoting hepatic ceramide synthesis leading to the establishment of a liver-brain axis of neurodegeneration.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated experimentally that limited exposure to sub-mutagenic doses of NDEA causes a triad of insulin-resistance diseases including T2DM, NASH, and AD-type neurodegeneration with sustained cognitive-motor deficits. The molecular and biochemical abnormalities detected are quite reminiscent of both human disease, and the effects of experimental i.c. STZ treatment [34]. These results raise serious concerns about our chronic, daily exposures to nitrosamines, either via environmental or dietary sources in relation to the growing epidemics of insulin resistance diseases. Since the effects of low-dose exposures are cumulative, further research is needed to characterize biomarkers and molecular/biochemical signatures of NDEA and other nitrosamine exposures in relation to insulin-resistance diseases in humans.

Table 5C.

NDEA Treatment Alters Expression of Genes Mediating Temporal Lobe Insulin and IGF Signaling

| mRNA* | Control (N = 8)* | NDEA (N = 16)* | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor | 4.364 ± 0.556 | 2.521 ± 0.238 | 0.0003 |

| IGF-I Receptor | 2.650 ± 0.277 | 2.980 ± 0.168 | |

| IGF-II Receptor | 2.349 ± 0.203 | 1.439 ± 0.118 | 0.0001 |

| Insulin | 0.038 ± 0.004 | 0.041 ± 0.004 | |

| IGF-I | 1.241 ± 0.286 | 0.634 ± 0.057 | 0.001 |

| IGF-II | 10.11 ± 1.823 | 12.31 ± 0.995 | |

| IRS-1 | 0.432 ± 0.047 | 0.677 ± 0.033 | < 0.0001 |

| IRS-2 | 3.996 ± 0.266 | 2.769 ± 0.183 | 0.0003 |

| IRS-4 | 0.142 ± 0.050 | 0.162 ± 0.034 |

mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR and values were normalized to 18s rRNA. Results depict the mean ± S.E.M. (×10−6) for each group. Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using T-test analyses. See abbreviations list in Table 1 legend.

Table 6B.

NDEA Activation of Ceramide Genes in Cerebellum

| mRNA* | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CerS2 | 2.91 ± 0.25 | 4.68 ± 0.51 | 0.002 |

| CerS4 | 0.95 ± 0.10 | 1.70 ± 0.20 | 0.001 |

| CerS5 | 4.85 ± 0.43 | 5.93 ± 0.80 | |

| UGCG | 7.72 ± 0.56 | 10.63 ± 1.37 | 0.029 |

| SMPD1 | 7.36 ± 0.80 | 10.00 ± 1.29 | 0.046 |

| SMPD3 | 2.90 ± 0.20 | 4.13 ± 0.53 | 0.018 |

| SPTLC1 | 0.027 ± 0.005 | 0.040 ± 0.006 | 0.049 |

| SPTLC2 | 0.385 ± 0.058 | 0.492 ± 0.056 |

Table 6C.

NDEA Activation of Ceramide Genes in Temporal Lobe

| mRNA* | Control | NDEA | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CerS2 | 4.08 ± 0.62 | 8.56 ± 1.50 | 0.013 |

| CerS4 | 2.28 ± 0.31 | 2.61 ± 0.26 | |

| CerS5 | 6.37 ± 0.91 | 7.87 ± 1.21 | |

| UGCG | 29.9 ± 2.83 | 32.6 ± 5.96 | |

| SMPD1 | ND | ND | |

| SMPD3 | 7.78 ± 1.50 | 15.4 ± 3.23 | 0.023 |

| SPTLC1 | ND | ND | |

| SPTLC2 | 2.09 ± 0.17 | 1.88 ± 0.27 |

mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR and values were normalized to 18s rRNA. Results depict the mean ± S.E.M. (×10−6) for each group. Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using T-test analyses. See abbreviations list in Table 1 legend. ND = not done because expression levels were too low.

Acknowledgments

Supported by AA-02666, AA-02169, AA-11431, AA-12908, and K24-AA-16126 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Wei Y, Ibdah JA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome: an update. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:185–192. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pradhan A. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes: inflammatory basis of glucose metabolic disorders. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S152–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Launer LJ. Next steps in Alzheimer’s disease research: interaction between epidemiology and basic science. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:141–143. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G, Silva J, Dasgupta S, Bieberich E. Long-chain ceramide is elevated in presenilin 1 (PS1M146V) mouse brain and induces apoptosis in PS1 astrocytes. Glia. 2008;56:449–456. doi: 10.1002/glia.20626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delgado JS. Evolving trends in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nugent C, Younossi ZM. Evaluation and management of obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:432–441. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Monte SM, Neusner A, Chu J, Lawton M. Epidemiological trends strongly suggest exposures are etiologic agents in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1070. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swann PF, Magee PN. Nitrosamine-induced carcinogenesis. The alklylation of nucleic acids of the rat by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea, dimethylnitrosamine, dimethyl sulphate and methyl methanesulphonate. Biochem J. 1968;110:39–47. doi: 10.1042/bj1100039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espey MG, Miranda KM, Thomas DD, Xavier S, Citrin D, Vitek MP, Wink DA. A chemical perspective on the interplay between NO, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen oxide species. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;962:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquier F, Boulogne A, Leys D, Fontaine P. Diabetes mellitus and dementia. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolls MR. The clinical and biological relationship between Type II diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2004;1:47–54. doi: 10.2174/1567205043480555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh MM, Brunt EM. Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:837–847. doi: 10.1309/RTPM1PY6YGBL2G2R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchesini G, Marzocchi R. Metabolic syndrome and NASH. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:105–117. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papandreou D, Rousso I, Mavromichalis I. Update on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pessayre D. Role of mitochondria in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(Suppl 1):S20–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei Y, Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Ibdah JA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mitochondrial dysfunction. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:193–199. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolzan AD, Bianchi MS. Genotoxicity of streptozotocin. Mutat Res. 2002;512:121–134. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossini AA, Like AA, Chick WL, Appel MC, Cahill GF., Jr Studies of streptozotocin-induced insulitis and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:2485–2489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szkudelski T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol Res. 2001;50:537–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doi K. Studies on the mechanism of the diabetogenic activity of streptozotocin and on the ability of compounds to block the diabetogenic activity of streptozotocin (author’s transl) Nippon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi. 1975;51:129–147. doi: 10.1507/endocrine1927.51.3_129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwai S, Murai T, Makino S, Min W, Morimura K, Mori S, Hagihara A, Seki S, Fukushima S. High sensitivity of fatty liver Shionogi (FLS) mice to diethylnitrosamine hepatocarcinogenesis: comparison to C3H and C57 mice. Cancer Lett. 2007;246:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Lester-Coll N, Plater M, Jr, Wands JR. Therapeutic rescue of neurodegeneration in experimental type 3 diabetes: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;10:89–109. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyer S. Causes and consequences of disturbances of cerebral glucose metabolism in sporadic Alzheimer disease: therapeutic implications. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;541:135–152. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8969-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoyer S, Lannert H, Noldner M, Chatterjee SS. Damaged neuronal energy metabolism and behavior are improved by Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) J Neural Transm. 1999;106:1171–1188. doi: 10.1007/s007020050232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lester-Coll N, Rivera EJ, Soscia SJ, Doiron K, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Intracerebral streptozotocin model of type 3 diabetes: relevance to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:13–33. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murata M, Takahashi A, Saito I, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA methylation and apoptosis: induction by diabetogenic streptozotocin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:881–887. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nukatsuka M, Sakurai H, Yoshimura Y, Nishida M, Kawada J. Enhancement by streptozotocin of O2- radical generation by the xanthine oxidase system of pancreatic beta-cells. FEBS Lett. 1988;239:295–298. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80938-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West IC. Radicals and oxidative stress in diabetes. Diabet Med. 2000;17:171–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robbiano L, Mereto E, Corbu C, Brambilla G. DNA damage induced by seven N-nitroso compounds in primary cultures of human and rat kidney cells. Mutat Res. 1996;368:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1218(96)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de La Monte SM, Tong M. Mechanisms of nitrosamine-mediated neurodegeneration: potential relevance to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1098. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyn-Cook LE, Lawton M, Tong M, Silbermann E, Longato L, Jiao P, Mark P, Wands JR, Xu H, de la Monte SM. Hepatic ceramide mediates brain insulin resistance and neurodegeneration in obesity with type 2 diabetes mellitus and Non-alcoholoic steatohepatitis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;16:715–729. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moroz N, Tong M, Longato L, Xu H, de la Monte SM. Limited Alzheimer-type neurodegeneration in experimental obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:29–44. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Review of insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression, signaling, and malfunction in the central nervous system: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:45–61. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Alzheimer’s Disease is Type 3 Diabetes: Evidence Reviewed. J Diabetes Science Tech. 2008;2:1101–1113. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamm RJ, Pike BR, O’Dell DM, Lyeth BG, Jenkins LW. The rotarod test: an evaluation of its effectiveness in assessing motor deficits following traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 1994;11:187–196. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickey RW, Akino M, Strausbaugh S, De Courten-Myers GM. Use of the Morris water maze and acoustic startle chamber to evaluate neurologic injury after asphyxial arrest in rats. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:77–84. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen AC, Tong M, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor resistance with neurodegeneration in an adult chronic ethanol exposure model. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1558–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soscia SJ, Tong M, Xu XJ, Cohen AC, Chu J, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Chronic gestational exposure to ethanol causes insulin and IGF resistance and impairs acetylcholine homeostasis in the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2039–2056. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heck DH, Zhao Y, Roy S, LeDoux MS, Reiter LT. Analysis of cerebellar function in Ube3a-deficient mice reveals novel genotype-specific behaviors. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2181–2189. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burwell RD, Saddoris MP, Bucci DJ, Wiig KA. Corticohippocampal contributions to spatial and contextual learning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3826–3836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0410-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duva CA, Floresco SB, Wunderlich GR, Lao TL, Pinel JP, Phillips AG. Disruption of spatial but not object-recognition memory by neurotoxic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:1184–1196. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.6.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirkby DL, Higgins GA. Characterization of perforant path lesions in rodent models of memory and attention. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:823–838. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinuma K, Matsuda J, Tanida N, Hori S, Tamura K, Ohno T, Kano M, Shimoyama T. N-nitrosamines in the stomach with special reference to in vitro formation, and kinetics after intragastric or intravenous administration in rats. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1990;25:417–424. doi: 10.1007/BF02779329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pec EA, Wout ZG, Johnston TP. Biological activity of urease formulated in poloxamer 407 after intraperitoneal injection in the rat. J Pharm Sci. 1992;81:626–630. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600810707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cave M, Deaciuc I, Mendez C, Song Z, Joshi-Barve S, Barve S, McClain C. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: predisposing factors and the role of nutrition. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sujatha SR, Pulimood A, Gunasekaran S. Comparative immunocytochemistry of isolated rat & monkey pancreatic islet cell types. Indian J Med Res. 2004;119:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cong WN, Tao RY, Tian JY, Liu GT, Ye F. The establishment of a novel non-alcoholic steatohepatitis model accompanied with obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Life Sci. 2008;82:983–990. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirsch R, Clarkson V, Verdonk RC, Marais AD, Shephard EG, Ryffel B, de la MHP. Rodent nutritional model of steatohepatitis: effects of endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) and tumor necrosis factor alpha deficiency. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:174–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshimatsu M, Terasaki Y, Sakashita N, Kiyota E, Sato H, van der Laan LJ, Takeya M. Induction of macrophage scavenger receptor MARCO in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis indicates possible involvement of endotoxin in its pathogenic process. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakhuja P, Malhotra V. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis–a histological perspective. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alessenko AV, Bugrova AE, Dudnik LB. Connection of lipid peroxide oxidation with the sphingomyelin pathway in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:144–146. doi: 10.1042/bst0320144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laviad EL, Albee L, Pankova-Kholmyansky I, Epstein S, Park H, Merrill AH, Jr, Futerman AH. Characterization of ceramide synthase 2: tissue distribution, substrate specificity, and inhibition by sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5677–5684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah C, Yang G, Lee I, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Samad F. Protection from high fat diet-induced increase in ceramide in mice lacking plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13538–13548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709950200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Summers SA. Ceramides in insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:42–72. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Altered Lipid Metabolism in Brain Injury and Disorders. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:241–268. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katsel P, Li C, Haroutunian V. Gene expression alterations in the sphingolipid metabolism pathways during progression of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a shift toward ceramide accumulation at the earliest recognizable stages of Alzheimer’s disease? Neurochem Res. 2007;32:845–856. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakane M, Kubota M, Nakagomi T, Tamura A, Hisaki H, Shimasaki H, Ueta N. Lethal forebrain ischemia stimulates sphingomyelin hydrolysis and ceramide generation in the gerbil hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2000;296:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiland D, Mondon CE, Reaven GM. Evidence for multiple causality in the development of diabetic hypertriglyceridaemia. Diabetologia. 1980;18:335–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00251016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease–is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grunblatt E, Koutsilieri E, Hoyer S, Riederer P. Gene expression alterations in brain areas of intracerebroventricular streptozotocin treated rat. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:261–271. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoyer S, Lannert H. Inhibition of the neuronal insulin receptor causes Alzheimer-like disturbances in oxidative/energy brain metabolism and in behavior in adult rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;893:301–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoyer S, Lee SK, Loffler T, Schliebs R. Inhibition of the neuronal insulin receptor. An in vivo model for sporadic Alzheimer disease? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:256–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lannert H, Hoyer S. Intracerebroventricular administration of streptozotocin causes long-term diminutions in learning and memory abilities and in cerebral energy metabolism in adult rats. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1199–1208. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Planel E, Tatebayashi Y, Miyasaka T, Liu L, Wang L, Herman M, Yu WH, Luchsinger JA, Wadzinski B, Duff KE, Takashima A. Insulin dysfunction induces in vivo tau hyperphosphorylation through distinct mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13635–13648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3949-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tahirovic I, Sofic E, Sapcanin A, Gavrankapetanovic I, Bach-Rojecky L, Salkovic-Petrisic M, Lackovic Z, Hoyer S, Riederer P. Reduced brain antioxidant capacity in rat models of betacytotoxic-induced experimental sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes mellitus. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1709–1717. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lijinsky W, Reuber MD, Riggs CW. Dose response studies of carcinogenesis in rats by nitrosodiethylamine. Cancer Res. 1981;41:4997–5003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lijinsky W, Saavedra JE, Reuber MD. Induction of carcinogenesis in Fischer rats by methylalkylnitrosamines. Cancer Res. 1981;41:1288–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bansal AK, Bansal M, Soni G, Bhatnagar D. Protective role of Vitamin E pre-treatment on N-nitrosodiethylamine induced oxidative stress in rat liver. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;156:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clapp NK, Craig AW, Toya RE., Sr Diethylnitrosamine oncogenesis in RF mice as influenced by variations in cumulative dose. Int J Cancer. 1970;5:119–123. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iizuka S, Suzuki W, Tabuchi M, Nagata M, Imamura S, Kobayashi Y, Kanitani M, Yanagisawa T, Kase Y, Takeda S, Aburada M, Takahashi KW. Diabetic complications in a new animal model (TSOD mouse) of spontaneous NIDDM with obesity. Exp Anim. 2005;54:71–83. doi: 10.1538/expanim.54.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Figueroa CD, Taberner PV. Pancreatic islet hypertrophy in spontaneous maturity onset obese-diabetic CBA/Ca mice. Int J Biochem. 1994;26:1299–1303. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen GJ, Xu J, Lahousse SA, Caggiano NL, de la Monte SM. Transient hypoxia causes Alzheimer-type molecular and biochemical abnormalities in cortical neurons: potential strategies for neuroprotection. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:209–228. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pylypiw HM, Zubroff JR, Magee PN, Harrington GW. The metabolism of N-nitrosomethylaniline. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1984;108:66–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00390975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singer GM, Taylor HW, Lijinsky W. Liposolubility as an aspect of nitrosamine carcinogenicity: quantitative correlations and qualitative observations. Chem Biol Interact. 1977;19:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(77)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Han MS, Park SY, Shinzawa K, Kim S, Chung KW, Lee JH, Kwon CH, Lee KW, Park CK, Chung WJ, Hwang JS, Yan JJ, Song DK, Tsujimoto Y, Lee MS. Lysophosphatidylcholine as a death effector in the lipoapoptosis of hepatocytes. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:84–97. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700184-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holland WL, Knotts TA, Chavez JA, Wang LP, Hoehn KL, Summers SA. Lipid mediators of insulin resistance. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]