Abstract

Thirteen patients who underwent 40% to 80% removal of their livers had blood samples drawn initially and daily on postoperative days 1 to 7. The enzyme marker of heightened polyamine metabolism, ornithine decarboxylase, and the indicator of DNA synthesis, thymidine kinase, were measured. In addition, the hormones (insulin, glucagon, estradiol and androgen), which in animals are known to reflect and possibly modulate regeneration, were measured. Changes in all these indices followed the same pattern as in rats, dogs and swine but at a slower rate. Ornithine decarboxylase and estradiol increased within 24 hr, but thymidine kinase and insulin rises did not become statistically significant until 3 to 5 days. Using these plasma or serum indices as surrogate measures of biochemical events in the liver itself, regeneration reached a maximum after 4 or 5 days. By computed tomography scan analysis, restoration of hepatic cell mass was not complete until 3 wk.

Liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy proceeds at different rates in different species; the rat has been the most completely studied species. Peak regeneration is at 24 hr in the rat (1–2), 48 hr in mice (3) and 72 hr in the dog (4) and in the pig (5). This chronology has been worked out by histopathological and biochemical analyses of samples of the remaining liver fragment at successive times after standard removal of half or more of the animals’ livers. The pace of hepatic regeneration in humans has not been precisely determined because serial tissue collection is neither feasible nor ethical.

There have been four widely accepted, quantitative measures of regeneration in liver tissues: (a) the number of hepatocytes in mitosis (1–2), (b) thymidine incorporation into hepatic DNA (6), (c) hepatic thymidine kinase (TK) activity as an indicator of DNA synthesis (5) and (d) activity of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) as an index of polyamine metabolism (7–11). Two of these parameters, TK and ODC, can be measured in the blood of hepatectomized rats (12), offering a practical and noninvasive method to study liver regeneration. These regeneration parameters have been shown to occur in relation to changes observed for plasma levels of insulin and glucagon (13–16) and the sex hormones (17–18).

We report here an investigation of 13 patients who had removal of a full liver lobe or more. All of the foregoing surrogate serum or plasma markers of hepatic regeneration were measured, permitting a better understanding of the events of liver regeneration in humans.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The patients were 24 to 72 yr old (Table 1). Six had metastases from colorectal cancer, two had primary hepatic malignancies and five had benign liver lesions. Only one patient had generalized parenchymal disease (hepatitis). Except for two patients with obstructive jaundice, liver function tests were normal or near normal. In addition to the 13 resection patients, three patients were studied who underwent elective cholecystectomy. On the morning of operation 10 ml of serum was obtained (time zero), and this collection was repeated daily for the next 7 days. All of the resection patients received parenteral nutrition postoperatively consisting of 1,800 to 2,100 total calories/day until a normal diet could be resumed.

TABLE 1.

Patients treated with partial hepatectomy

| Patient No. |

Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Associated disease | Type of hepatectomy | Degree of liver resection (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | M | Metastatic C.C. | No | R. trisegmentectomy | 75 |

| 2 | 51 | M | Metastatic C.C. | Ulcerative colitis | L. lobectomy | 40 |

| 3 | 58 | M | Metastatic C.C. | Hepatitis | R. lobectomy | 60 |

| 4 | 30 | M | Multiple stones within intrahepatic bile ducts | No | R. lobectomy | 60 |

| 5 | 63 | F | Metastatic C.C. | No | R. trisegmentectomy | 75 |

| 6 | 42 | F | Focal nodular hyperplasia | No | R. trisegmentectomy | 75 |

| 7 | 67 | M | Liver metastasis from Klatskin tumor | Severe cholestasis | L. lobectomy | 60 |

| 8 | 40 | F | Cavernous hemangioma | No | R. trisegmentectomy | 80 |

| 9 | 45 | M | Metastatic C.C. | No | R. lobectomy | 50 |

| 10 | 54 | F | Hepatic adenocarcinoma | No | R. trisegmentectomy | 80 |

| 11 | 24 | F | Focal nodular hyperplasia | No | L. trisegmentectomy | 75 |

| 12 | 50 | F | Hemangioma | No | R. lobectomy | 50 |

| 13 | 61 | F | Metastatic C.C. | No | R. lobectomy | 50 |

R = Right; L = Left; C.C. = colon cancer.

The quantity of liver removed was expressed as a percent of total liver volume determined by preoperative determination of liver and mass of the resection specimen.

The resections are listed in Table 1. Estimated liver volumes were measured preoperatively with computed tomography (CT). Then, liver weight was estimated (19) with the formula:

The percent of liver removed was estimated by:

Plasma Insulin Assays

Immunoreactive insulin was determined by RIA using a kit obtained from Serono Diagnostic SA, Coinsins, Switzerland. The detection limit of this assay in our laboratory is 5 µU/ml, and the coefficient of variation for replicate samples is 8.4%.

Plasma Glucagon Assays

Immunoreactive glucagon was determined with a kit that has known accuracy, precision and specificity (Serono Diagnostic SA). One milliliter of blood was collected in chilled tubes containing 500 units of aprotinin (Trasylol, a trypsin inhibitor) and 1.2 mg sodium EDTA. The detection limit for this assay in our laboratory is 15 pg/ml, and the coefficient of variation is 9.6%. In representative blood samples obtained from each patient, a gel filtration technique (20) was used to subdivide the IRG into that with molecular weights of 3,500, 7,000 and 40,000 Da. The gel filtration studies demonstrated that the IRG found in these patients was predominantly the form having a molecular weight of 3,500 Da, which is the most biologically active form (21).

Assays of Serum Estradiol and Testosterone

Levels were determined with 125-I solid phase direct RIA kits (lmmunochern Corp., Carson, CA). The sensitivity for the estradiol kit and for the testosterone kit is 10 pg and 0.2 ng, respectively. The intraassay coefficient of variation (CV) in our laboratory is 6% for estradiol and 10.9% for the testosterone assay. The interassay CV was 11.3% for the estradiol kit and 11.2% for the testosterone kit.

Enzyme Assays of Plasma ODC

Five milliliters of blood was collected in a tube containing 1 00 µl of the following solution: 5 mmo/L pyridoxal phosphate, 100 mmo/L 1,4-dithiothreitol, 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, and 5 µl TWEEN/80:. ODC was determined (22) by measurement of the amount of putrescine formed in vitro from l-(2m-3-3H)-ornithine as substrate with specific activity of 50.4 Ci/mmol from New England Nuclear (Boston, MA).

Enzyme Assays of TK

The enzyme activity was determined in 25 µl serum by measuring the rate of conversion of 125I-iododeoxycitidine. This assay is more sensitive than the traditional one that used thymidine and is more accurate when small serum samples are used (23).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were performed using a least squares regression and Student’s t test; a value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are required as the mean ± S.E.M.

RESULTS

The patients with resection and the three who had cholecystectomy recovered without serious complications. They were stable medically throughout the period of the study. The restoration of original hepatic mass in the resection patients required approximately 3 wk as estimated from weekly CT scans.

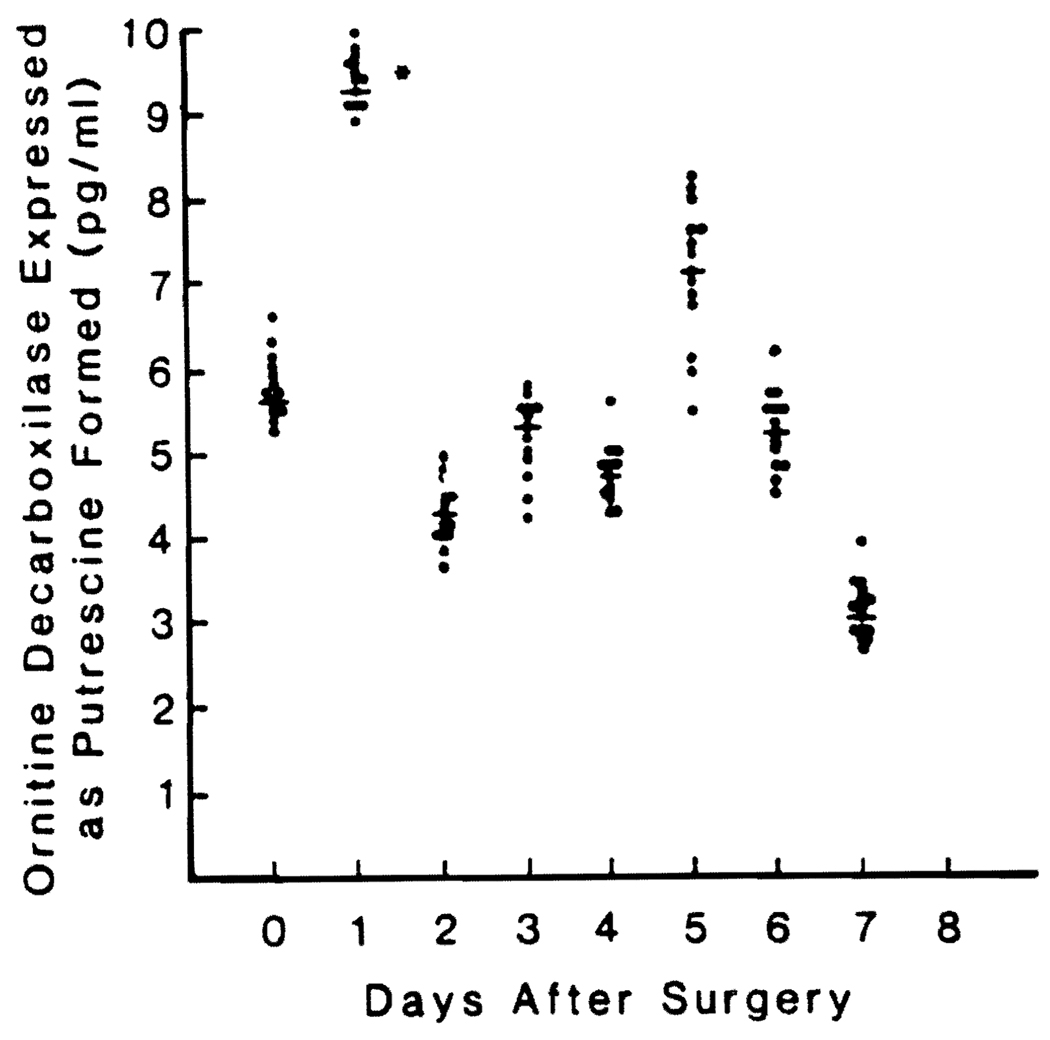

Changes in Plasma ODC Levels

There was a significant increase in plasma ODC within 24 hr (Fig. 1) followed by a return to preoperative values by the end of the second postoperative day. There was a second short-lived increase on the fifth postoperative day that was not significant.

FIG. 1.

Preoperative and postoperative ODC blood levels in 13 patients undergoing major liver resection. Values are reported as means ± S.D. *Significantly different from control value, p < 0.05.

ODC did not change in the three control patients, being similar to the preoperative values.

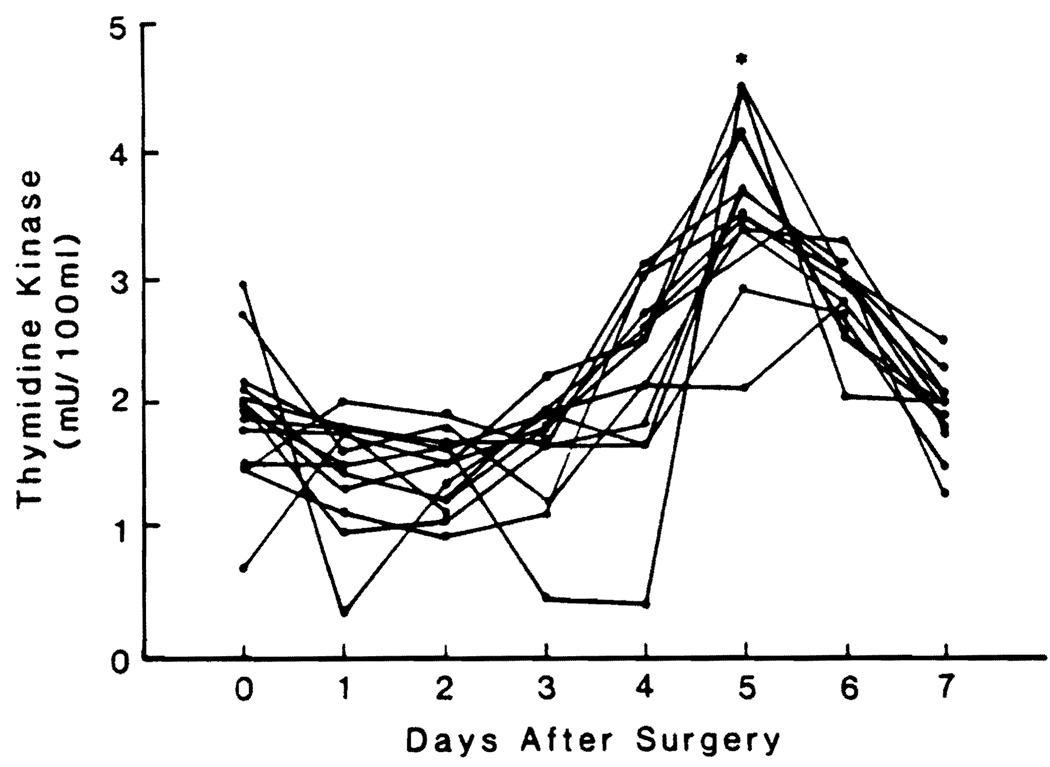

Changes in Plasma TK Activities

TK activity did not begin to increase until day 3, and the increase usually lasted for 3 or 4 days (Fig. 2). For the whole group, the TK rise was significant only on day 5.

FIG. 2.

Preoperative and postoperative TK blood levels in 13 patients undergoing major liver resection. Values are reported as means ± S.D. *Significantly different from control value, p < 0.05.

TK did not change in the three control patients.

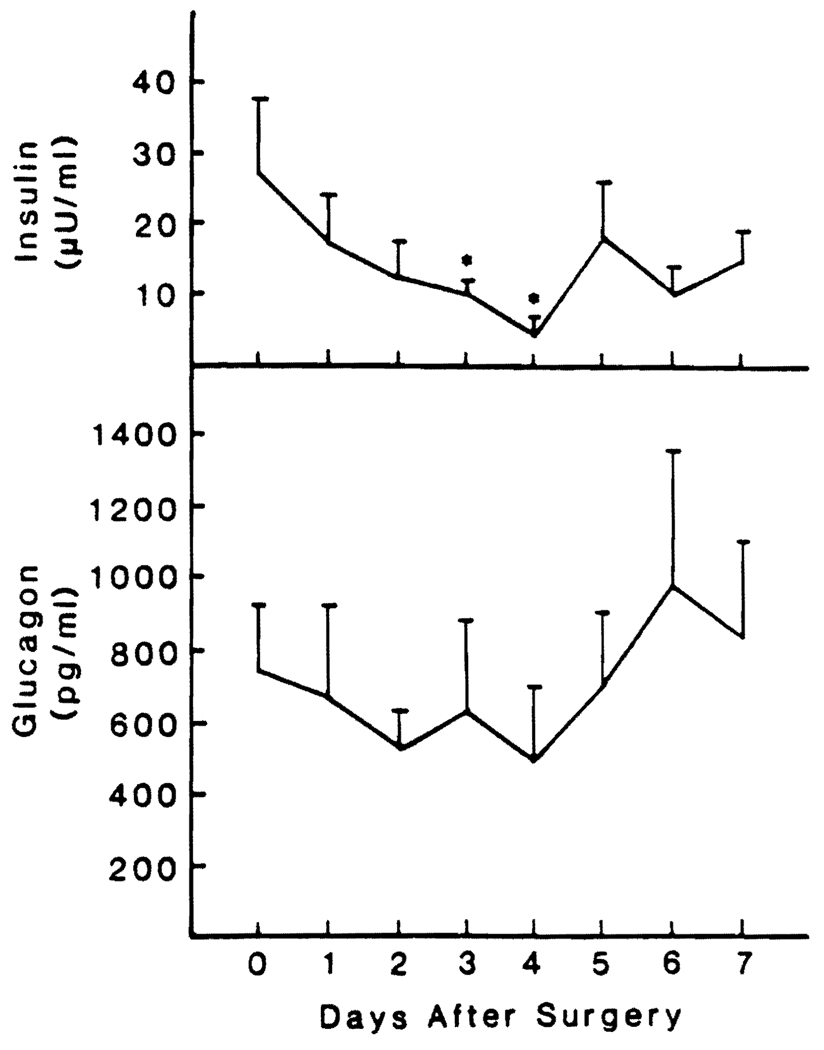

Changes in Insulin and Glucagon Levels

The insulin levels were in the normal range before operation and decreased slowly during the first 4 days after hepatic resection. The reductions were significant at 72 hr and 96 hr (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Preoperative and postoperative insulin and glucagon blood levels in 13 patients undergoing major liver resection. The values are reported as means ± S.D. *Significantly different from control value, p < 0.05.

The average plasma concentration of IRG was four times normal preoperatively and was not changed significantly during the observation period (Fig. 3).

The three control patients who underwent a cholecystectomy did not have significant changes in the glucagon and insulin levels (data not shown).

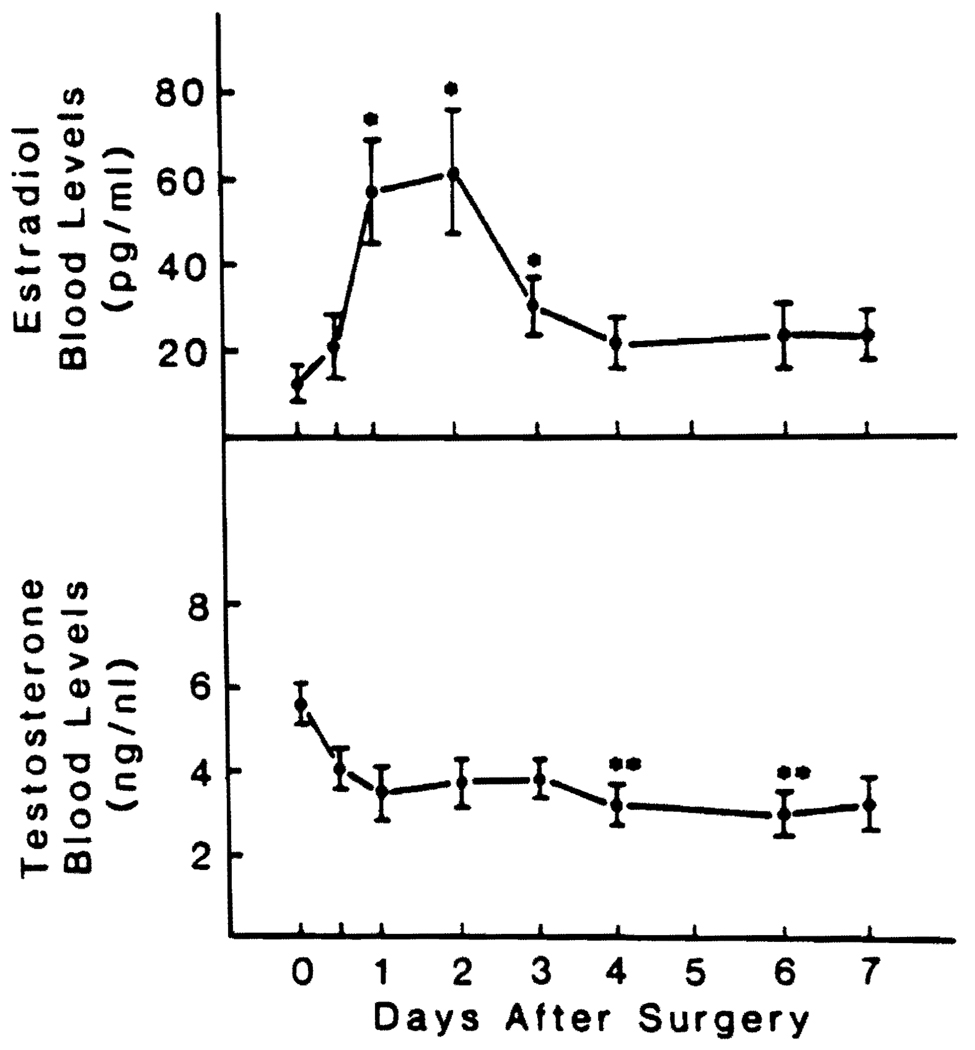

Changes in Estradiol and Testosterone Levels

Seven of the patients were men. Their estradiol levels rose sharply and peaked at 48 hr (Fig. 4). The estradiol increases were significant (p < 0.05) 24, 48 and 72 hr after resection. Testosterone decreased significantly (p < 0.02) at 92 and 144 hr (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Preoperative and postoperative E2 and testosterone blood levels in seven men undergoing major liver resection. Values are reported as means ± S.D. *Significantly different from control value, p < 0.05. **Significantly different from control value, p < 0.02.

The six women that had partial hepatectomy had widely different serum estradiol levels that reflected their considerable variability in age (Table 2). The partial hepatectomy did not lead to a statistically significant change, either in the E2 or in testosterone plasma levels.

TABLE 2.

Estradiol and testosterone blood levels in women undergoing major hepatectomy

| A | Estradiol blood levels (pg/mI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days before and after surgery | |||||||||

| Patient no. | Age | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 6 | 42 | 91.2 | 116.0 | 99.1 | 115.2 | 124.2 | 96.0 | 150.0 | 130.0 |

| 8 | 40 | 209.0 | 95.5 | 150.1 | 240.8 | 220.0 | 148.0 | 108.0 | 121.0 |

| 10 | 54 | 39.7 | 84.8 | 84.6 | 45.8 | 48.8 | 49.4 | 42.1 | 40.1 |

| 11 | 24 | 241.6 | 56.3 | 84.1 | 119.3 | 50.0 | 56.5 | 116.0 | 140.0 |

| 12 | 50 | 82.4 | 95.0 | 36.6 | 44.5 | 101.4 | 60.6 | 32.2 | 62.8 |

| 13 | 61 | 80.0 | 85.0 | 40.1 | 50.3 | 70.1 | 72.3 | 48.8 | 70.1 |

| B | Testosterone blood levels (pg/mI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days before and after surgery | |||||||||

| Patient no. | Age | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 6 | 42 | 0.27 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.38 |

| 8 | 40 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 1.62 | 0.87 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.43 |

| 10 | 54 | 0.5 | 2.62 | 2.51 | 2.07 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.50 | 1.25 |

| 11 | 24 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.91 | 0.65 |

| 12 | 50 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.21 |

| 13 | 61 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.45 |

None of the three patients having a cholecystectomy had a significant change in their serum sex hormone levels.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated (12) that ODC and TK plasma levels are a reliable mirror of what is happening in the liver of the rat, offering a practical and noninvasive method for a complete study of liver regeneration in humans. In the patients studied, a significant increase of ODC, an enzyme required for increased polyamine synthesis, was seen 24 hr after partial hepatectomy (8–10). The increase of ODC was followed 3 or 4 days later by a significant increase of TK, a marker of DNA synthesis. The sequential appearance in the blood of ODC and TK was similar to that in animals, differing only quantitatively. It has been anticipated that such might be possible recently by Koch and Leffert (24). In rats, the rapidity with which regeneration occurs makes the interval short between the early activity of ODC and the subsequent increases of TK (12). The dog (4) and pig (5) have a slower progression of these changes, and in the human studies reported herein, 3 or 4 days seem to exist between the initial events signaled by the ODC and the wave of DNA synthesis measured with TK. This slower pace of regeneration was also reflected by the CT scan studies that showed that regeneration was not complete until 3 wk as opposed to 8 to 10 days in the rat (2) and 14 days in the dog (4).

The pancreatic hormone changes observed followed a more protracted schedule in humans. Avid insulin-binding to hepatocytes with a subsequent decline in plasma insulin levels occurs within 12 hr in rats (15–16) but was not seen in the patients studied over 3 days. Hyperglucagonemia, which is seen early in animals (4), was not observed in the patients studied, possibly because the baseline glucagon levels were four times greater than normal, possibly as a result of the underlying liver disease. In contrast, changes in the sex hormones in men occurred briskly after hepatectomy and were already evident within a few hours. These alterations in sex hormone levels were not seen in women who already have high levels of estradiol. We have speculated before that for regeneration to occur in Inale animals, the liver must first become feminized (25).

In this preliminary investigation no attempt to assay tumor growth factor activity in blood was attempted because no assay for substances was available to us. Clearly in the future an attempt to measure tumor growth factor in such cases would be of considerable interest based on the recent studies of Brenner, Koch and Leffert (26) and Mead and Fausto (27).

The slow-motion nature of the regeneration process in humans could make possible the separation of the Initiating, augmenting and permission factors that are required for the full expression of the regeneration potential. The use of the surrogate markers of regeneration that we have used in our studies may make it possible to more completely characterize mechanisms of liver regeneration in humans.

Acknowledgments

Supported by awards from the Veterans Administration and project grants No. AM-29961, AM-30001 and AM-31577 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland and by grant No. 87/0129144 from the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinbren K. Regeneration of the liver. Gastroenterology. 1959;37:657–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bucher NLR, Malt RA. Morphological and biological aspects. In: Bucher NLR, Malt RA, editors. Regeneration of liver and kidney. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.; 1971. p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimura S, Ramada N. Effect of cyclosporin A on liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy in the mouse. Transplant Proc. 1989;21:911–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francavilla A, Porter KA, Benichou J, Jones AF, Starzl TE. Liver regeneration in dogs: morphologic and chemical changes. J Surg Res. 1978;25:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(78)80005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn D, Stadler J, Terblanche J, Van Hoorn-Hickman R. Thymidine kinase: an inexpensive index of liver regeneration in a large animal model. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:907–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giles KW, Myers A. An improved diphenylamine method for the estimation of deoxyribonucleic acid. Nature. 1965;206:93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGowan JA, Fausto N. Ornithine decarboxylase activity and the onset of deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in regenerating liver. Biochem J. 1978;170:123–127. doi: 10.1042/bj1700123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCann PP. Regulation of ornithine decarboxylase in eukaryotes. In: Gauges JM, editor. Polyamines in biomedical research. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachrach U. The induction of ornithine decarboxylase in normal and neoplastic cells. In: Gauges JM, editor. Polyamines in biomedical research. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell DR. Ornithine decarboxylase as a biological and pharmacological tool. Pharmacology. 1980;20:117–129. doi: 10.1159/000137355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bello LS. Regulation of thymidine kinase synthesis in human cells. Exp Cell Res. 1974;89:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(74)90790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polimeno L, Azzarone A, Dell'Aquila P, Amoruso C, Barone M, Angelini A, Van Thiel DR, et al. Relationship between plasma and hepatic cytosolic levels of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and thymidine kinase (TK) in 70% hepatectomized rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1990 doi: 10.1007/BF01318198. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morley CGD, Kuku S, Rubenstein HN, Boyer SL. Serum hormone levels following partial hepatectomy in rat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;67:663–668. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leffert H, Alexander NM, Faloona G, Rubalcava B, Unger R. Specific endocrine and hormonal receptor changes associated with liver regeneration in adult rats. Proe Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4033–4036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.10.4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pezzino V, Vigneri R, Cohen 0, Goldifine ID. Regenerating rat liver, insulin and glucagon serum levels and receptor binding. Endocrinology. 1981;108:2163–2169. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-6-2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leffert HL, Koch KS, Moran T, Rubalcava B. Hormonal control of rat liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:1470–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francavilla A, DiLeo A, Eagon PI, Wu SQ, Ove P, Van Thiel DR, Starzl TE. Regenerating rat liver: correlations between estrogen receptor localization and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:552–557. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francavilla A, Gavaler JS, Makowka L, Barone M, Mazzaferro V, Ambrosino G, Iwatsuki S, et al. Estradiol and testosterone levels in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy: a possible signal for hepatic regeneration? Dig Dis Sci. 1989;6:818–822. doi: 10.1007/BF01540264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Thiel DH, Hagler NG, Schade RR, Skolnick ML, Heyl AP, Rosenblum E, Gavaler JS, et al. In vivo hepatic volume determination using sonography and computed tomography. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1812–1817. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny AJ, Say RR. Glucagon like activity extractable from the gastrointestinal tract of man and other animals. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:1–7. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0250001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dudley FS, Alford FP, Chisholm OJ, Findlay OM. Effect of portasystemic venous shunt surgery on hyperglucagonaemia in cirrhosis: varied studies of pre- and post-shunted subjects. Gut. 1979;20:8817–8824. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.10.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber LWD. A practicable variant of the ion exchange method for the radiometric estimation of ornithine decarboxylase activity. Experientia. 1974;43:176–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01942841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gronowitz JS, Kallander CFR. Optimized assay for thymidine kinase and its application to the detection of antibodies against herpes simplex virus type 1- and 2-induced thymidine kinase. Infect Immun. 1980;29:425–434. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.2.425-434.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch KS, Leffert HL. Do transplanted human livers regenerate? HEPATOLOGY. 1989;9:789–793. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francavilla A, Eagon PI, Di Leo M, Polimeno L, Panella C, Aquilino AM, Ingrosso M, et al. Sex hormone-related functions in regenerating male rat iiver. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(86)80026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenner DA, Koch KS, Leffert HL. Transforming growth factor-alpha stimulates proto-oncogene c-jun expression and a mitogenic program in primary cultures of adult rat hepatocytes. DNA. 1989;8:279–285. doi: 10.1089/dna.1.1989.8.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mead JE, Fausto N. Transforming growth factor alpha may be a physiological regulator of liver regeneration by means of an autocrine mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1558–1562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]