Abstract

BRCA2 is an important tumor suppressor and functions in homologous recombination, a key genomic integrity pathway. BRCA2 interacts with RAD51, the central protein of recombination, which forms filaments on ssDNA to perform homology search and DNA strand invasion. We report the purification of full-length human BRCA2, and show that it binds to ~6 RAD51 molecules and promotes RAD51 binding to RPA-covered ssDNA in a manner that is stimulated by DSS1.

Germline mutations in the BRCA2 gene confer a highly elevated lifetime risk of developing breast, ovarian, and other cancers 1. The tumor suppressor function relates to a role of BRCA2 protein in homologous recombination 2, but the mechanistic analysis of human BRCA2 has been impeded by difficulties purifying this large protein (3,418 amino acids). BRCA2 contains 8 conserved BRC repeats and a C-terminal region that bind RAD51 with varying affinity 3,4 and is required for RAD51 localization to sites of DNA damage 5. RAD51 filament formation on ssDNA is inhibited by the binding of the ssDNA-binding protein RPA to the substrate. Filament formation requires the action of mediator proteins 6, and seminal studies of the much shorter fungal and nematode BRCA2 homologs and of isolated domains of human BRCA2 have led to a model in which BRCA2 nucleates RAD51 polymerization at DNA junctions to overcome the inhibitory effect of RPA 7–13. However, this model has not been tested yet in the context of the full-length human BRCA2 protein.

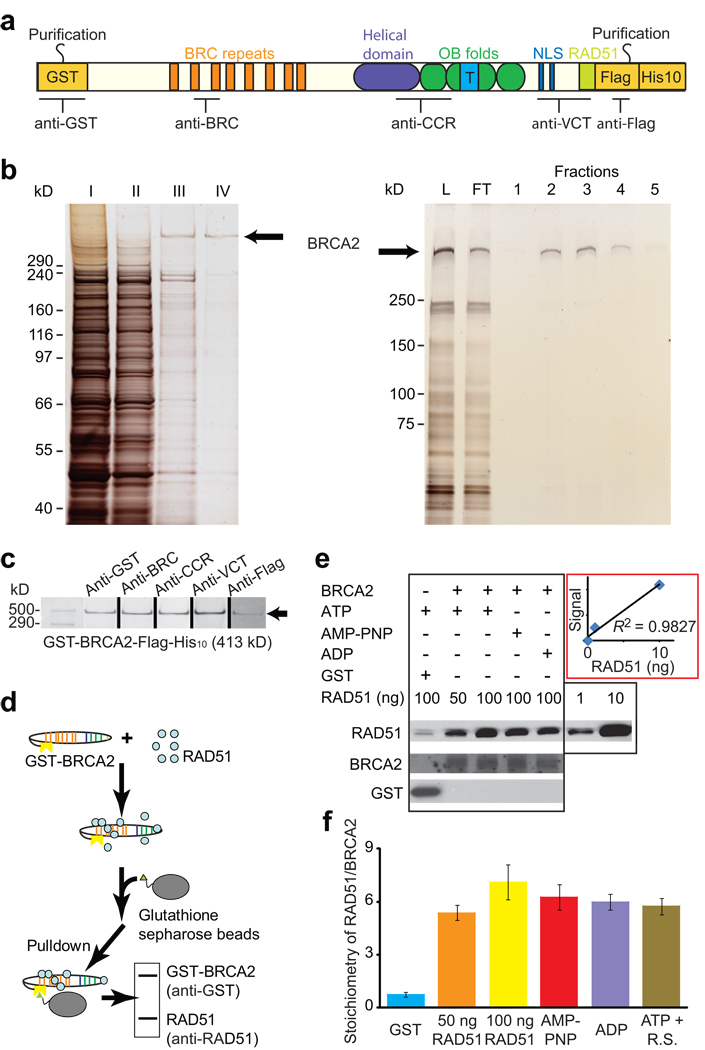

To examine the function of human BRCA2 in homologous recombination, we have purified to near homogeneity small quantities of full-length human GST-BRCA2-FLAG-His10 expressed in yeast. Using N- and C-terminal affinity tags, we selected specifically for full-length protein (Fig. 1a), with the presence of both tags verified by retention of the protein on the affinity resins (Fig. 1b) and by immunoblotting using anti-GST and anti-FLAG antibodies (Fig. 1c). Antibodies directed to interstitial regions of human BRCA2 (BRC, CCR, VCT, in Fig. 1a) confirmed the presence of these epitopes (Fig. 1c). By SDS-PAGE, purified full-length human GST-BRCA2-FLAG-His10 migrated in a manner consistent with a predicted molecular weight of 413 kDa within the limit of resolution of these gels (Fig. 1c). To further confirm the integrity of the purified protein, we resequenced the entire gene from the overproduction yeast strain after protein purification and confirmed the absence of any rearrangements or mutations. From here on, we refer to GST-BRCA2-FLAG-His10 as BRCA2.

Figure 1. Purification of human BRCA2 and interaction with RAD51.

(a) Schematic representation of purified human BRCA2 protein. (b) BRCA2 purification analysis. Left: Silver-stained fractions from purification steps: I, lysate. II, pooled fraction after ammonium sulfate precipitation. III, pooled fraction of GSTrap eluate. IV, fraction from anti-FLAG column eluate. Right: Analysis of FLAG column load (L), flow through (FT), and fractions by PAGE and silver staining. (c) Immunoblotting with antibodies spanning the full-length tagged BRCA2 protein as indicated in a. (d) GST pull-down assay design. (e) Immunoblots and (f) quantitation of the proteins in pull-down assay. The reactions contain 4.65 nM (50 ng) or 9.30 nM (100 ng) RAD51, 0.1 nM (10 ng) or no BRCA2, and 1 mM AMP-PNP, ADP, or ATP. R.S.: Regenerating system. Error bars represent s.d. of n=3.

Previous studies could not define the stoichiometry of the BRCA2-RAD51 interaction in humans, as the homologs from model organisms contain fewer BRC repeats (1 BRC repeat in the case of the best studied homolog Brh2 from Ustilago maydis 13) and the purified human domains or synthetic constructs did not contain all RAD51 binding sites or the proper structural context 7,9–12. To determine the stoichiometry of the BRCA2-RAD51 interaction, we used a GST-pull-down assay with excess RAD51 (Fig. 1d), and measured the amounts of pulled-down proteins by quantitative immunoblot (see Supplementary Methods). This analysis confirms that BRCA2 binds human RAD51 protein in solution and indicates a stoichiometry of about 6 ± 1 RAD51 per BRCA2 (Fig. 1e). This estimate hinges on the accuracy of the BRCA2 concentration, but is consistent with an independent measurement using a different full-length human BRCA2 protein 14. While RAD51 can bind different nucleotide cofactors, but we found that the RAD51-BRCA2 interaction is only marginally influenced by the nucleotide cofactor bound to RAD51 (Fig. 1f). Nucleation is the rate-limiting step for RAD51 filament formation, and single-molecule experiments have estimated that about 2–3 RAD51 protomers are sufficient for filament nucleation 15, although other estimates are higher at 4–5 protomers 16. In either case, our results indicate that BRCA2 can bind sufficient RAD51 molecules to promote RAD51 filament nucleation.

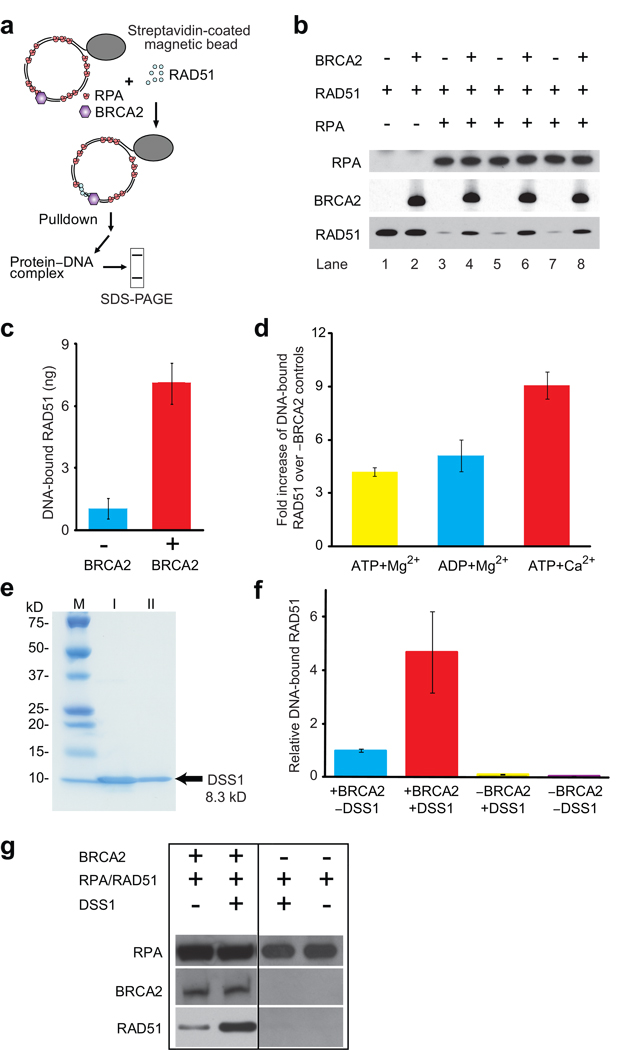

The assembly of the RAD51-ssDNA filament is inhibited by RPA, and mediator proteins, including BRCA2, are thought to overcome this inhibition to facilitate the formation of RAD51 filaments on RPA-coated ssDNA 6. To test this model with full-length human BRCA2 protein, we used a magnetic bead-based pull-down assay to measure the binding of RAD51 to RPA-coated ssDNA (Fig. 2a). In the presence of saturating amounts of RPA fully occupying the available ssDNA (1 RPA per 10 nt), we observed little RAD51 binding. Addition of BRCA2 resulted in a 7-fold stimulation of RAD51 binding to RPA-coated ssDNA (Fig. 2b, c). Use of the purified, full-length BRCA2 protein was critical, as preparations containing BRCA2 truncation/degradation products inhibited rather than stimulated RAD51 binding to RPA-coated ssDNA (data not shown). BRCA2-mediated stimulation of RAD51 binding to RPA-coated ssDNA occurred at a sub-stoichiometric ratio of 1 BRCA2 molecule to 33 RAD51 protomers. Non-specific binding of RAD51 to dsDNA or to the bead can be ruled out, as the BRCA2 effect is dependent on the presence of RPA (Fig. 2b; lanes 1, 2). The amount of RAD51 bound to ssDNA is not expected to lead to an appreciable decrease in bound RPA, because of the small amounts of BRCA2 and RAD51 present in the reactions and the limited cooperativity of RAD51.

Figure 2. BRCA2 promotes RAD51 binding to RPA-covered gapped DNA.

(a) Assay design. (b) Immunoblots of the proteins bound to immobilized gapped DNA substrates. Reactions contain 0.2 µM (nt concentration) ssDNA, 0 or 20 nM RPA, 13.3 nM RAD51 (1 RAD51 per 15 nucleotides), and 0 or 0.4 nM (25 ng) BRCA2. (c) Quantitation of DNA-bound RAD51 shown in b. (d) Quantitation of DNA-bound RAD51 in the presence of different nucleotide cofactors. BRCA2 was 0.32 nM (20 ng), all other components were as in b. Plotted is fold increase over controls lacking BRCA2. (e) Purification of human DSS1 protein. I, pooled fraction of chitin column eluate. II, pooled fraction of Mono-Q column eluate. (f) Immunoblots of the proteins bound to immobilized gapped DNA substrates. Reaction contained 0.2 µM (nt concentration) ssDNA, 20 nM RPA, 13.3 nM RAD51 (1 RAD51 per 15 nucleotides), 0 or 4 nM DSS1, and 0 or 0.08 nM (5 ng) BRCA2. (g) Quantitation of DNA-bound RAD51 shown in b. Plotted is fold increase over absence of DSS1. Error bars represent s.d. of n=3, and in one case n=2.

BRCA2-mediated stimulation of RAD51 binding to RPA-coated ssDNA was highest with ATP + Ca2+, a condition that stabilizes the active, ATP-bound form of RAD51 on ssDNA 17 (Fig. 2d). This is consistent with previous data showing that the BRC4 peptide inhibited the RAD51 ATPase activity 11, thereby maintaining the active form of RAD51 17.

Previous studies have suggested that BRCA2 orthologs show a preference for binding single-stranded/double-stranded DNA junctions 8. However, when we compared the binding of BRCA2 to an ssDNA circle or a gapped DNA substrate containing 9 junctions (five 5’ and four 3’ junctions), no significant difference was seen (Supplementary Fig. 1) consistent with findings in ref. 14. It is possible that other proteins (PALB2, RAD51 paralogs) impart junction specificity.

BRCA2 associates with the small (70-amino acid) DSS1 protein, which is required for recombinational repair but whose mechanism has been enigmatic 18–20. Addition of purified human DSS1 (Fig. 2e) alone did not stimulate RAD51 binding to RPA-covered ssDNA (Fig. 2f,g). In contrast, in the presence of BRCA2, RAD51 binding to RPA-covered ssDNA was stimulated about 5-fold by DSS1 above that observed by BRCA2 alone. These results indicate a direct, positive role of DSS1 in recombinational DNA repair and are consistent with genetic data in human cells and model organisms showing that DSS1 is required in vivo for recombinational DNA repair, RAD51 focus formation, and genomic stability 19,20.

Purification of full-length human BRCA2 and DSS1 represents a critical breakthrough that sets the stage for structural and functional studies of this important human tumor suppressor complex in its native context and allows for direct examination of the molecular defects associated with BRCA2 or DSS1 polymorphisms or mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Marc Wold (University of Iowa) and Patrick Sung (Yale University) for antibodies and overexpression vectors, and Steve Kowalczykowski for sharing unpublished results and helpful comments, as well as Neil Hunter, Kirk Ehmsen, Erin Schwartz, William Wright, Xiao-Ping Zhang, Damon Meyer, Jessica Sneeden, and Clare Fasching for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from TRDRP (17FT-0046), NIH (GM58015, CA92276), DoD (DAMD17-00-1-0187), the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (BCTR0201259), and the UC Davis Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available.

Author contributions

J.L. designed, performed, analyzed all experiments, and helped write the manuscript. T.D., J.L., and B.G. purified BRCA2 and DSS1. W.D.H. conceived the project, designed experiments, contributed to data analysis and wrote the manuscript with J.L. with contributions from all authors.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Wooster R, et al. Nature. 1995;378:789–791. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moynahan ME, Pierce AJ, Jasin M. Mol Cell. 2001;7:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00174-5. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong AKC, Pero R, Ormonde PA, Tavtigian SV, Bartel PL. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31941–31944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esashi F, et al. Nature. 2005;434:598–604. doi: 10.1038/nature03404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan SSF, et al. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3547–3551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.San Filippo J, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11649–11657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601249200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang HJ, et al. Science. 2002;297:1837–1848. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5588.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang HJ, Li QB, Fan J, Holloman WK, Pavletich NP. Nature. 2005;433:653–657. doi: 10.1038/nature03234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies AA, et al. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esashi F, Galkin VE, Yu X, Egelman EH, West SC. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:468–474. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreira A, et al. Cell. 2009;136:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.019. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saeki H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8768–8773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojic M, Kostrub CF, Buchman AR, Holloman WK. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen RB, Carreira A, Kowalczykowski SC. Nature. 2010;xxx:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1038/nature09399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilario J, Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Kowalczykowski SC. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:361–368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811965106. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Heijden T, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5646–5657. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bugreev DV, Mazin AV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9988–9993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402105101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marston NJ, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4633–4642. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kojic M, Yang HJ, Kostrub CF, Pavletich NP, Holloman WK. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudmundsdottir K, Lord CJ, Witt E, Tutt ANJ, Ashworth A. EMBO Reports. 2004;5:989–993. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.