Abstract

Aims

Although several cultured endothelial cell studies indicate that sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), via GTPase Rac1 activation, enhances endothelial barriers, very few in situ studies have been published. We aimed to further investigate the mechanisms whereby S1P modulates both baseline and increased permeability in intact microvessels.

Methods and results

We measured attenuation by S1P of platelet-activating factor (PAF)- or bradykinin (Bk)-induced hydraulic conductivity (Lp) increase in mesenteric microvessels of anaesthetized rats. S1P alone (1–5 µM) attenuated by 70% the acute Lp increase due to PAF or Bk. Immunofluorescence methods in the same vessels under identical experimental conditions showed that Bk or PAF stimulated the loss of peripheral endothelial cortactin and rearrangement of VE-cadherin and occludin. Our results are the first to show in intact vessels that S1P pre-treatment inhibited rearrangement of VE-cadherin and occludin induced by PAF or Bk and preserved peripheral cortactin. S1P (1–5 µM, 30 min) did not increase baseline Lp. However, 10 µM S1P (60 min) increased Lp two-fold.

Conclusion

Our results conform to the hypothesis that S1P inhibits acute permeability increase in association with enhanced stabilization of peripheral endothelial adhesion proteins. These results support the idea that S1P can be useful to attenuate inflammation by enhancing endothelial adhesion through activation of Rac-dependent pathways.

Keywords: Capillary permeability, Inflammation, Rac1, cAMP, Rap1

1. Introduction

Microvascular endothelium is the primary barrier to and regulator of solute and solvent exchange between blood and tissue. In individually perfused microvessels, various mediators induce an acute inflammatory reaction that is characterized by a transient breakdown of the barrier function of endothelium through localized loss of adhesion and transient opening of small gaps between the endothelial cells lasting on the order of 10min. Such permeability increases are a model for increased permeability in a variety of pathological states leading to oedema and compromised organ function. They also provide a useful model to investigate mechanisms that attenuate increased permeability. Reports from several laboratories including our own demonstrate that both elevated intracellular cAMP and activation of signalling pathways by sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) in endothelial cells attenuate increased permeability.1–8 Although some of the actions of elevated cAMP can be attributed to a reduction of tension development in endothelial cells after exposure to agents such as thrombin, there is increasing evidence that the principal action of cAMP and S1P to attenuate increased vascular permeability involves regulation of adhesion between endothelial cells leading to junction complex stabilization.9–12

An emerging concept is that mechanisms that strengthen endothelial cell–cell adhesion are a common and essential feature of the action of agents that protect the endothelial barrier after exposure to injury and inflammatory conditions.4,13,14 Mechanisms to strengthen adhesion involve increased polymerization of cortical actin in endothelial cells, linkage of actin-binding proteins to the cortical network, and tighter adhesion between molecular complexes associated with the peripheral actin band and molecules forming the adherens junction and the tight junction.15 We previously demonstrated that acute inhibition of the small GTPase Rac1 using bacterial toxin (Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin) causes a large increase in permeability of venular microvessels, measured as hydraulic conductivity (Lp), as well as cultured endothelial monolayers.14 The increase in permeability is associated with a reduction of F-actin content by 50% and similar fractional reduction in VE-cadherin-mediated adhesion of coated beads to endothelium. In a separate study, preferential activation of Rac by the bacterial toxin cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1 (CNF-1) significantly attenuated the increased permeability induced by platelet-activating factor (PAF).16 Our observations that activation of Rac results in the protection of the endothelial barrier against acute inflammatory mediators is consistent with several recent reports that S1P, which also activates Rac, enhances the endothelial permeability barrier in vivo,4 in situ,6 and in vitro.5

The aim of the present experiments was to further evaluate the mechanisms whereby S1P modulates both baseline and elevated permeability in intact venular microvessels. Several important questions remain unanswered. For example, the most detailed investigations of S1P-dependent modulation of endothelial cell–cell adhesion have been carried out in cultured endothelial monolayers which have less well-formed junctions than intact mammalian microvessels. We therefore investigated changes in the distribution of VE-cadherin, occludin, and cortactin in intact microvessels in the control state and after exposure to inflammatory agents with and without the presence of S1P. Furthermore, preliminary investigations showed that S1P only partially attenuated increased permeability, in contrast with the action of elevated cAMP. cAMP acts via many pathways including activation of Rap117 which may induce actin stabilization via Rac1.18–20 To address the mechanism of S1P action, we demonstrated activation of Rac in a cultured endothelial cell system and correlated Rac activation with stabilization of peripheral cytoskeletal components, and then, we used nearly identical solutions and conditions to test for comparable cytoskeletal response in intact microvessels. We found using intact microvessels that S1P blocked the acute permeability response to both bradykinin (Bk) and PAF and that it induced a moderate reduction in baseline Lp. Only at the highest concentration tested (10 µM), did S1P moderately increase permeability. The permeability experiments as well as our immunofluorescence investigations were consistent with the hypothesis that the primary action of S1P is to stabilize the endothelial adhesion complex of intact microvessels through activation of Rac-dependent pathways and its effectiveness was not compromised except at very high concentration.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal preparation and measurements to characterize vessel wall permeability

Experiments were carried out on male rats anaesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg body weight, sc) and maintained by giving additional pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, sc) as needed. At the end of experiments, animals were euthanized with saturated KCl. The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Animal protocols (07-13052) were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis, CA, USA. Experiments were performed on venular mesenteric microvessels (ca. 25–35 µm dia.). Hydraulic conductivity (Lp) was measured to characterize vessel wall permeability. Experiments were based on the modified Landis technique, which measures the volume flux of water crossing the wall of a microvessel perfused via a glass micropipette following occlusion of the vessel. Assumptions and limitations have been evaluated in detail.1,21 See Supplementary material online for further details.

2.2. Confocal microscopy of immunolabelled mesenteries

Mesenteries were flooded with ice-cold fixative, incubated with primary antibodies against VE-cadherin, occludin, and cortactin, labelled with fluorescent secondary antibodies, and then mounted for confocal microscopy. Tissues were mounted whole to retain the three-dimensional structure of the vessels and, when possible, to enable separate collection of either front (near to lens) or rear half of each vessel. Stacks were projected onto a single plane for analysis. See Supplementary material online for further details.

2.3. Solutions and reagents

The following stock solutions were prepared: PAF (1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; Calbiochem 511075) (1 mM) in EtOH, Bk (Sigma, B3259) (1 mM) in water, and S1P (1 mM) in EtOH.

2.4. Cell culture

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC; Clonetics) were seeded at high density (near confluence) on collagen-coated tissue culture-treated polystyrene and cultured for up to 3 days. Immunofluorescence: HMVEC were serum starved for 16 h prior to treatment with S1P, then cells were fixed in freshly depolymerized paraformaldehyde and labelled with anti-VE-cadherin and anti-cortactin.

2.5. Rac activation assay

HMVEC were serum starved for 16 h prior to treatment with S1P or vehicle. Relative level of RacGTP was determined using a colorimetric ELISA-based assay (Rac1,2,3 activation assay, Cytoskeleton). Samples were processed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.6. Analysis and statistics

To examine the modulation of response to PAF or Bk, we tested the response in each vessel twice, first in the absence of other agents and second in the presence of a test reagent. Therefore, each vessel acted as its own control. Throughout, averaged Lp values were reported as mean ± SEM. The indicated statistical tests were performed assuming significance for probability levels <0.05.

3. Results

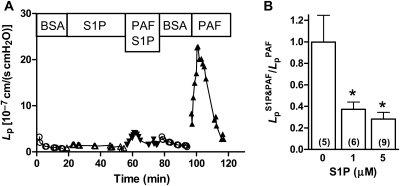

3.1. S1P inhibits inflammatory response to PAF

Representative experimental data from an individual experiment show Lp measured over 120 min (Figure 1A). After initial perfusion with vehicle solution, the vessel was pre-treated by perfusion with S1P (1 µM) for 30 min. Responsiveness to PAF (10 nM) was then tested in the continued presence of S1P and a small response was noted. After the Lp returned to near baseline during perfusion with vehicle solution, the response to PAF of the same vessel was tested in the absence of S1P and a much larger response was recorded. Some vessels were tested initially with PAF alone and then treated with S1P prior to a second PAF test. The results showed inhibition due to S1P comparable to those seen in Figure 1A and were pooled for analysis. A further group of experiments demonstrated that repeated PAF treatments in the absence of S1P elicited similar Lp peaks; the ratio of the first peak to the second peak was 1.00 ± 0.25 (first column of Figure 1B). The inhibition of the PAF response measured as the ratio of peak Lp in the presence of S1P to the peak Lp in the absence of S1P is summarized in Figure 1B. S1P at either 1 or 5 µM significantly attenuated the Lp response to near 35% of the peak Lp measured without inhibition.

Figure 1.

(A) S1P inhibits acute Lp response to PAF. Representative data from one experiment show that treatment with S1P (1 µM) inhibits the first test with PAF (10 nM), whereas a second test in the absence of S1P after recovery to baseline shows a typical PAF response. (B) Dose–response relation for inhibition of PAF by S1P. The ratio of the peak Lp response to PAF (10 nM) in the presence of S1P to the peak value in the absence of S1P is shown. Both 1 and 5 µM S1P inhibit about 65% of the acute Lp peak response. Control value shows that repeated treatment with PAF yields comparable peaks (*different from control, P < 0.05, Wilcoxon's signed-rank test, n for each group shown in parentheses).

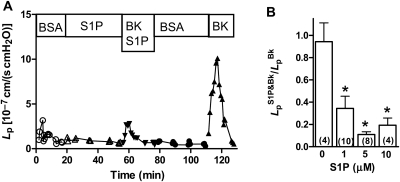

3.2. S1P also inhibits inflammatory response to Bk

To test the generality of S1P inhibition, Bk was used as a second inflammatory mediator that also induces a transient Lp increase in perfused venules. Data from a representative experiment show that S1P produces a strong inhibition of the Lp response to Bk (Figure 2A). Data averaged from several experiments indicate that S1P (1 µM) inhibits about 65% of the peak Lp response to Bk (10 nM); in a separate set of experiments using higher concentrations of S1P (5 and 10 µM), the response to Bk was more strongly attenuated (Figure 2B). In the absence of S1P, repeated Bk treatments induced comparable Lp peaks in control experiments; the ratio of the first peak to the second peak was 0.94 ± 0.17 (first column of Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) S1P inhibits acute Lp response to Bk. Using the same experimental design as in Figure 1 for PAF experiments, S1P (1 µM) is shown to partially inhibit the acute peak Lp response to Bk (10 nM) during the first Bk test Lp these data from a representative vessel. After recovery to baseline, the second Bk test responds with a typical rapid increase and recovery. (B) Dose–response relation for S1P inhibition of Bk. S1P at 1, 5, and 10 µM strongly reduces the peak Lp response to Bk (10 nM), but even at the highest concentration it does not fully block the response. Repeated tests in the absence of S1P show that multiple Bk tests yield similar peaks (*different from control, P < 0.05, Wilcoxon's signed-rank test, n for each group shown in parentheses).

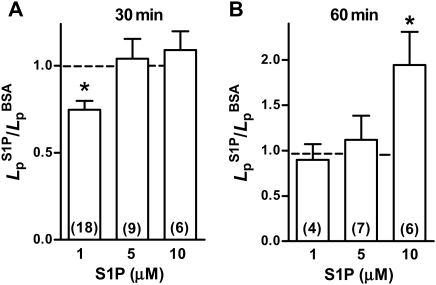

3.3. Effect on baseline Lp

One published report using cultured endothelial cells indicated that S1P at high concentration (≥5 µM) induced a loss of barrier function in endothelial cells.22 This was in contrast to reports that physiological concentrations of S1P (10 nM to 2 µM) improved barrier function.4 Therefore, we tested whether S1P alone had an effect on baseline Lp. At the lowest concentration (1 µM), S1P after 30 min induced a small but statistically significant decrease in Lp (Figure 3A). We observed no change in Lp with either 5 or 10 µM S1P after 30 min. Only after 60 min of continuous perfusion with S1P at the highest concentration tested (10 µM), was there an approximate doubling of the Lp from 1.0 ± 0.2 × 10−7 cm/(scmH2O) to 1.9 ± 0.4 × 10−7 cm/(scmH2O) (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon's matched pairs test; n = 6). After 60 min of perfusion with either 1 or 5 µM S1P, there was no difference from initial control values.

Figure 3.

Effect of S1P on baseline Lp. (A) The ratio of Lp measured after 30 min of S1P relative to the value measured with vehicle solution alone is shown. Only at 1µM is the Lp significantly reduced to about 70% of control. At higher concentrations, there was no significant difference from control (*different from value of 1; P < 0.05, Wilcoxon's signed-rank test, n for each group shown in parentheses). (B) The ratio of Lp measured after 60 min of S1P relative to the Lp in the absence of S1P is shown. With 1 or 5 µM, there was no change from control. At 10 µM, S1P Lp increased by about two-fold (*different from value of 1; P < 0.05, Wilcoxon's signed-rank test, n for each group shown in parentheses).

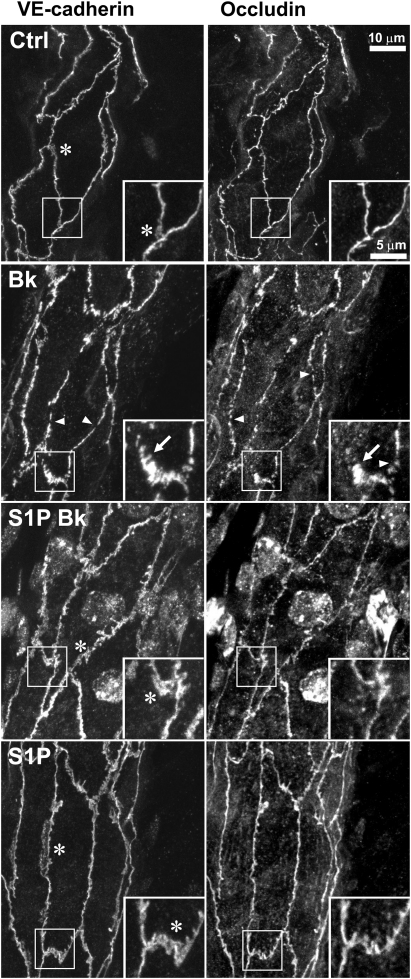

3.4. Localization of junction components VE-cadherin and occludin in vivo

We previously documented that the elevated permeability state induced by PAF was associated with small discontinuities (ca. 1 µm) and rearrangement of both VE-cadherin and occludin revealed by immunofluorescence in rat mesentery microvessels.1 Figure 4 shows that Bk induces similar rearrangement of these two junction molecules and that pre-treatment with S1P inhibits the rearrangement. Treatment with S1P alone did not produce any noticeable change from the continuous peripheral distribution of VE-cadherin or occludin that is seen in control images.

Figure 4.

S1P prevents rearrangement of VE-cadherin and occludin in vivo. Segment of a vessel wall dual labelled for VE-cadherin and occludin from a vessel perfused with vehicle solution (Ctrl) shows continuous label for both proteins. (The images are projections from stacks of images taken of three-dimensional vessel wall so that some junctions appear to be incomplete where they pass out of the collection volume.) A representative vessel that was perfused with Bk (10 nM, 5 min) shows discrete gaps (arrowheads) in both VE-cadherin and occludin, as well as spikes oriented perpendicularly to the junction (arrows). The Lp of the Bk-treated vessel was 14 × 10−7 cm/(s cmH2O) immediately before fixation (Lp values of Ctrl, S1P-Bk, and S1P vessels were 1.2, 1.4, and 0.8, respectively, i.e. they were low and normal). In vessels pre-treated with S1P (5 µM, 30 min) prior to Bk, there were no prominent gaps or rearrangements of the junction protein patterns (S1P-Bk). Vessels treated with S1P alone (5 µM, 30 min) looked very similar to vehicle controls with continuous junctions and exhibited broad areas of VE-cadherin (asterisks).

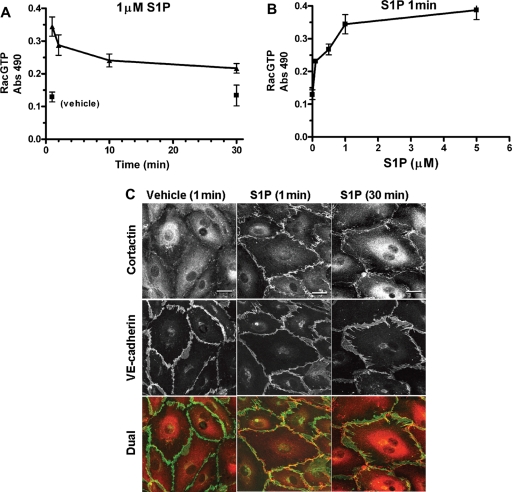

3.5. Effect of S1P on Rac activation and cortactin localization in HMVEC culture

For cultured endothelium, S1P increases RacGTP (Rac1 activation) and induces peripheral actin.5 Although we had no assay for Rac activation that could be used for the perfused microvessels in situ, we wanted to test for cortactin localization in microvessels using S1P treatment conditions similar to those which activate Rac in cultured endothelial cells (see below). In order to establish the parallel treatments, we first tested the S1P effect on Rac activation and cortactin localization using cultured human dermal microvascular endothelium (HMVEC). The time and concentration dependence of Rac activation in these cells using S1P is shown in Figure 5. There was a strong Rac activation within 1 min relative to vehicle control that declined slowly, but remained above control for 30 min (Figure 5A). The S1P concentration dependence at 1 min showed a pronounced and nearly equal response for 1 and 5 µM (Figure 5B); both 1 and 5 µM S1P produce strong inhibition of the Lp response to Bk (Figure 2). We then used 1 µM S1P to test for effects on cortactin and VE-cadherin localization in HMVEC (Figure 5C). Quiescent cells showed very slight and incomplete peripheral cortactin and continuous peripheral VE-cadherin. Treatment with S1P for 1 min stimulated a strong peripheral localization of cortactin that remained well above control for 30 min. Distribution of VE-cadherin was not changed by S1P treatment in monolayers that were fully confluent and serum starved. These results confirm previous observations that S1P induces Rac activation associated with enhanced peripheral endothelial cortactin localization in cultured endothelial cells. The same S1P stock solutions, final concentration, and timing were used to treat mesenteric microvessels below.

Figure 5.

Effects of S1P on cultured HMVEC. (A) Rac activation, shown over time when exposed to S1P (1 µM), rapidly rises relative to vehicle treatment and remains elevated for at least 30 min (mean ± SEM). (B) Dose–response relationship for Rac activation in the presence of S1P (1 min) shows that level of activation at 1 µM is nearly equal to that at 5 µM. (C) Representative cultures of HMVEC double labelled for cortactin and VE-cadherin show that treatment with 1 µM S1P induces strong peripheral cortactin at both 1 and 30 min relative to vehicle control. VE-cadherin after S1P treatment was not different from fully confluent, quiescent monolayers. Scale bar 20 µm.

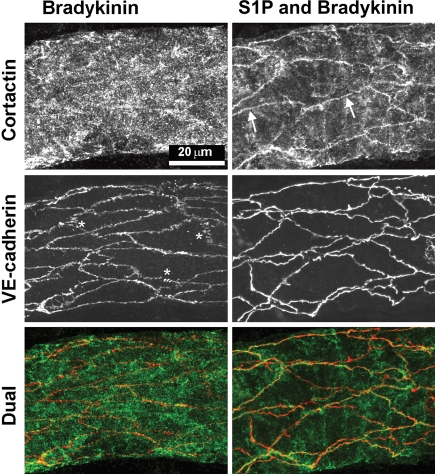

3.6. Effect of S1P on cortactin localization in microvessels

To examine the effects of S1P on the localization of cortactin in intact vessels, we compared Bk inflammatory stimulation (10 nM Bk, 5 min) with Bk stimulation in the presence of S1P (Figure 6). In Bk-treated vessels, we were unable to find peripheral cortactin; the VE-cadherin was peripheral, but had numerous small gaps and many lateral spikes as described above and similar to PAF treatment. In contrast, when vessels were pre-treated with S1P (5 µM, 30 min) and then exposed briefly to Bk (in continued presence of S1P), the cortactin was readily seen to be peripheral (Figure 6, arrows). We also examined control vessels treated with S1P alone and found that cortactin was peripherally located (data not shown). In summary, Bk-treated vessels lose peripheral cortactin; S1P prevents the rearrangement that we otherwise see with Bk.

Figure 6.

S1P localizes cortactin to periphery in vivo. Representative vessels, perfused with Bk (10 nM) and pre-treated with S1P (5 µM, 30 min) prior to Bk, respectively, were dual labelled for cortactin and VE-cadherin. The Bk vessel [final Lp was 34 × 10−7 cm/(scmH2O)] shows distinctive gaps and lateral spikes (asterisks) in VE-cadherin, whereas the vessel pre-treated with S1P prior to Bk [final Lp was 2 × 10−7 cm/(scmH2O)] had continuous VE-cadherin. Cortactin was diffuse in the vessel wall of the Bk vessel, but in the S1P pre-treated vessel, cortactin was clearly enhanced at the periphery of many endothelial cells (arrows) where it is seen near the VE-cadherin in the dual label image. (When these specimens were mounted, the vessels collapsed and therefore the labelled endothelial junctions from opposite sides of the vessel appear to cross one another.)

4. Discussion

Our principal results indicate that S1P attenuated the acute Lp response that was induced by either PAF or Bk in the venular microvessels of rat mesentery. The attenuation of the Lp response corresponded to an inhibition of the rearrangement of VE-cadherin and occludin that was otherwise induced by PAF or Bk. Treatment with S1P also preserved peripheral cortactin localization during Bk challenge in endothelial cells of the mesenteric microvessels. Treatment of microvessels with S1P at 1 µM for up to 30 min induced a partial decrease in baseline Lp, whereas higher concentrations showed no change in Lp. However, in vessels that were perfused with 10 µM S1P for 60 min, the Lp did increase about two-fold. These observations confirm and extend previous reports to show that S1P inhibits the acute permeability from increasing the effects of inflammatory modulators in intact vessels and that this is associated with an enhanced stabilization of peripheral actin-associated junction components. Further, under conditions of our experiments, S1P moderately increases permeability only at the highest concentration used (10 µM) and when present for 60 min.

This study provides further tests using intact microvessels of the hypothesis that stabilization of the endothelial–endothelial adhesion complex can protect against permeability increasing the effects of inflammatory modulators. Activation of Rac1 by action of S1P on endothelial receptors has been reported to both strengthen cultured endothelial monolayers and protect vascular permeability barriers in vivo.4,6,8,23 The bacterial toxin CNF-1 is known to activate Rac1 in endothelial cells and we previously demonstrated in perfused microvessels that CNF-1 (300 ng/mL, 120 min) pre-treatment results in strong inhibition of the Lp response to PAF.16 Our present results demonstrate comparable attenuation of PAF-induced increases in permeability by S1P and CNF-1, even though these two agents act via different signalling pathways leading to Rac1 activation. In contrast, we note that one recent study suggests that Rac1 activation via a PAF receptor-activated pathway is associated with barrier breakdown in a cultured human umbilical vein model.24 A weakness of our present results is that we did not demonstrate directly in vivo that Rac1 was activated as a result of S1P treatment. However, the strength of our approach was that we demonstrated, using endothelial cell culture, that the same stock solution of S1P (also dilutions and timing of treatment) that induced strong Rac activation and promoted cortactin localization in culture was also effective in vivo to block the acute Lp increase that otherwise was induced by either PAF or Bk.

We also demonstrated that S1P promoted peripheral cortactin localization and prevented re-organization of either VE-cadherin or occludin. This observation corresponds to previous studies showing that cortactin is translocated to the endothelial cell periphery in cultured cells by direct activation of Rac,16 by treatment with S1P,25 and by increased cAMP.26 Specifically, cortactin translocation and interaction with Arp2/3 in lamellipodia in endothelial migration has been shown to depend on interaction of S1P1 with Akt kinase.27 To our knowledge, the present data are the first to demonstrate S1P-dependent cortactin translocation to the endothelial cell periphery in intact microvessels. Thus, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that S1P protects the vascular permeability barrier in vivo through stabilization of the adhesion complex.

On the basis of extensive cultured endothelial cell studies, S1P ligation of receptor S1P1 activates a Gi/PI3kinase/Akt-dependent pathway leading to Rac1-dependent stabilization of the peripheral actin cytoskeleton and enhanced endothelial cell–cell adhesion that provides attenuation of acute inflammatory stimulation.4,27 In the present results, S1P alone provided an incomplete attenuation of the Lp response to PAF or Bk relative to the nearly complete inhibition that we, and others, have demonstrated by stimulation of cAMP (using a combination of rolipram and forskolin), suggesting that cAMP affects additional pathways not stimulated by S1P.1,6,28 cAMP activates multiple signalling pathways including a Rap1 pathway and the well-known PKA-dependent pathways to both stabilize endothelial adhesion and strongly inhibit inflammatory stimuli.9,11 The Rap1 pathway may also induce actin stabilization by interaction with the Rac1 pathway by inducing localization near the endothelial periphery of the Rac1 guanine nucleotide exchange factors Tiam1 and Vav2, thus further inducing inflammatory inhibition.18,19,29 Although these data suggest that activation of the Epac/Rap1 pathway in addition to the S1P/Gi/PI3kinase/Akt/Rac1 pathway could provide inhibition equal to that of cAMP, they do not exclude the possibility of converging effects of cAMP on both PKA- and Epac-regulated mechanisms.26,29 One interpretation of these results is that signalling pathways that stabilize tight junctions between endothelial cells act in parallel with Rac-dependent pathways that stabilize actin and adherens junctions. Alternative actions of cAMP have been suggested,30 in which specific phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) acts to further stabilize endothelial barrier by facilitating Rac1 activation possibly within a scaffolding complex31 or phosphor-VASP may contribute to junction stability through integrin recruitment to the cell periphery.32 The action of cAMP to attenuate contractile mechanisms is not likely to be significant in these acute inflammatory responses as we have shown that inhibition of myosin light chain kinase, myosin ATPase, and Rho kinase do not block PAF-induced increases in permeability.1 We speculate that regulation of Rac1 and Rap1 is modified in endothelial cells during chronic inflammation to induce an endothelial phenotype with reduced capacity to maintain normal permeability. In the absence of chronic inflammation, stabilization of junctions via cAMP pathways or S1P-dependent Rac1 activation provides strong inhibition against the acute permeability increases stimulated by PAF or Bk.

In contrast to the prominent inhibitory effect on acute inflammatory mediators, we found mixed results for the effect of S1P on basal Lp. At the lowest concentration (1 µM), there was a 30% decrease in Lp over 30 min relative to the initial vehicle control, whereas neither 5 nor 10 µM changed Lp over that time. Moreover, in experiments that ran to 60 min, the Lp of the 1 µM group returned to equal the vehicle control value, whereas the 10 µM group increased to twice the vehicle control (as discussed below). The 30% decrease measured with the 1 µM, 30 min treatment is similar to the decrease in Lp previously reported that is induced by increasing intracellular cAMP by treatment with a combination of rolipram (inhibitor of cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase 4) and forskolin (activator of adenylate cyclase).9 In the present study, we excluded vessels with a basal vehicle Lp greater than 2.5 × 10−7 cm/(scmH2O) as being abnormally high. We found no correlation of the decrease in Lp using S1P (1 µM, 30 min) with the initial basal Lp. In contrast, the only other study of Lp in single vessels found no effect on basal Lp for vessels in the normal range, but did find that S1P was able to reduce the Lp of vessels having higher than normal basal Lp.6 Using a variety of cultured endothelial cell types, it was reported that S1P reduces basal permeability (measured as trans-monolayer electrical resistance).5 However, this effect in cultured cells appears to be in large part due to induction of cell spreading not associated with cell–cell adhesion.33

We found that S1P treatment did not induce any change in the basal distribution of VE-cadherin or occludin in the intact microvasculature. Similarly, we recently found that neither cAMP (either stimulated by forskolin and rolipram) nor the cAMP analogue that preferentially activates the Epac/Rap1 pathway induces any change in the basal distribution of VE-cadherin or occludin.9 We interpret this to mean that for non-activated in situ endothelium, these adhesion proteins are maximally localized to the junctions. This is in contrast to reports that S1P increases the localization of VE-cadherin in cultured cells with treatments ranging from 10 to 60 min.33–35 It is known that in many cell culture preparations, the basal state is not as tight as in situ endothelium and there is the ability to modulate the permeability to either lower or higher values. We were unable to find any change due to S1P treatment in the basal VE-cadherin distribution in our cultured HMVEC monolayers. The one element of our culture conditions that seemed ultimately to produce the best monolayers was to seed the cells at very high density (near confluence). Another possible explanation of the difference is that the dermal microvascular cells respond better to culture conditions than the cell types used in the studies mentioned above. If there were any increase in peripheral VE-cadherin (in response to S1P) in either our basal condition cultured monolayers or our in situ endothelium, it was small enough to be not detectable by immunofluorescence.

However, we also noted that when S1P was perfused at the highest concentration (10 µM) for 60 min, the Lp was moderately (about two-fold), but significantly, increased. One speculation is that down-regulation of S1P receptors could account partially for the increase in Lp at 60 min. We also note that Rac1 activation is an essential step in NADPH oxidase-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS),36 which may be associated with endothelial barrier compromise.37 If the latter is significant, then one predicts that scavenging ROS might prevent an increase in Lp due to the high S1P treatment. Whatever the mechanism, these data indicate that S1P increases permeability if given at a high enough concentration and, if generally true, would limit the potential utility of S1P in clinical therapy. Previous studies suggested that S1P at concentrations above 2 µM induced increased permeability and was associated with activation of stress fibres in cultured endothelial cells.22 Because the 10 µM concentration is well above that necessary to inhibit PAF or Bk, it appears not to compromise the potential utility of S1P to provide a protective effect on the endothelial barrier.

In summary, S1P appears to act in vivo by stimulation of Rac-dependent pathways to stabilize the peripheral endothelial adhesion complex. Although it blocks the acute permeability response to multiple inflammatory mediators, it does not do so as effectively as stimulation of intracellular cAMP. Only at high concentration and with long exposure, does S1P increase permeability. These results from intact microvessels provide further support for the general hypothesis that inflammation can be modulated by enhancing or maintaining endothelial adhesion and support the idea that S1P-dependent pathways are appropriate targets for inflammatory modulation.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

Supported by the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number HL28607).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Adamson RH, Zeng M, Adamson GN, Lenz JF, Curry FE. PAF- and bradykinin-induced hyperpermeability of rat venules is independent of actin-myosin contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H406–417. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00021.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia JG, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:510–522. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630311. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041630311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW. Targets for pharmacological intervention of endothelial hyperpermeability and barrier function. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39:257–272. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00014-4. doi:10.1016/S1537-1891(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McVerry BJ, Garcia JG. In vitro and in vivo modulation of vascular barrier integrity by sphingosine 1-phosphate: mechanistic insights. Cell Signal. 2005;17:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.08.006. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, Birukova A, Dechert MA, Gerthoffer WT, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:689–701. doi: 10.1172/JCI12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minnear FL, Zhu L, He P. Sphingosine 1-phosphate prevents platelet-activating factor-induced increase in hydraulic conductivity in rat mesenteric venules: pertussis toxin sensitive. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H840–844. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00026.2005. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00026.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stelzner TJ, Weil JV, O'Brien RF. Role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in the induction of endothelial barrier properties. J Cell Physiol. 1989;139:157–166. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041390122. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041390122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JF, Gordon S, Estrada R, Wang L, Siow DL, Wattenberg BW, et al. Balance of S1P1 and S1P2 signaling regulates peripheral microvascular permeability in rat cremaster muscle vasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H33–H42. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00097.2008. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00097.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamson RH, Ly JC, Sarai RK, Lenz JF, Altangerel A, Drenckhahn D, et al. Epac/Rap1 pathway regulates microvascular hyperpermeability induced by PAF in rat mesentery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1188–H1196. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00937.2007. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00937.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogatcheva NV, Verin AD. The role of cytoskeleton in the regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kooistra MR, Corada M, Dejana E, Bos JL. Epac1 regulates integrity of endothelial cell junctions through VE-cadherin. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4966–4972. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.080. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. doi:10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullere X, Shaw SK, Andersson L, Hirahashi J, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function by Epac, a cAMP-activated exchange factor for Rap GTPase. Blood. 2005;105:1950–1955. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1987. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-05-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waschke J, Baumgartner W, Adamson RH, Zeng M, Aktories K, Barth H, et al. Requirement of Rac activity for maintenance of capillary endothelial barrier properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H394–H401. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00221.2003. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00221.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dejana E, Orsenigo F, Lampugnani MG. The role of adherens junctions and VE-cadherin in the control of vascular permeability. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2115–2122. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017897. doi:10.1242/jcs.017897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waschke J, Burger S, Curry FR, Drenckhahn D, Adamson RH. Activation of Rac-1 and Cdc42 stabilizes the microvascular endothelial barrier. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;125:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0080-2. doi:10.1007/s00418-005-0080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:733–738. doi: 10.1038/nrm1197. doi:10.1038/nrm1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arthur WT, Quilliam LA, Cooper JA. Rap1 promotes cell spreading by localizing Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:111–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404068. doi:10.1083/jcb.200404068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumer Y, Spindler V, Werthmann RC, Bunemann M, Waschke J. Role of Rac 1 and cAMP in endothelial barrier stabilization and thrombin-induced barrier breakdown. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:716–726. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21819. doi:10.1002/jcp.21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birukova AA, Zagranichnaya T, Alekseeva E, Bokoch GM, Birukov KG. Epac/Rap and PKA are novel mechanisms of ANP-induced Rac-mediated pulmonary endothelial barrier protection. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:715–724. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21354. doi:10.1002/jcp.21354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel CC, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:703–761. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shikata Y, Birukov KG, Garcia JG. S1P induces FA remodeling in human pulmonary endothelial cells: role of Rac, GIT1, FAK, and paxillin. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:1193–1203. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00690.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tauseef M, Kini V, Knezevic N, Brannan M, Ramchandaran R, Fyrst H, et al. Activation of sphingosine kinase-1 reverses the increase in lung vascular permeability through sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor signaling in endothelial cells. Circulation research. 2008;103:1164–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000338501.84810.51. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000338501.84810.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knezevic II, Predescu SA, Neamu RF, Gorovoy MS, Knezevic NM, Easington C, et al. Tiam1 and Rac1 are required for platelet-activating factor-induced endothelial junctional disassembly and increase in vascular permeability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5381–5394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808958200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M808958200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudek SM, Jacobson JR, Chiang ET, Birukov KG, Wang P, Zhan X, et al. Pulmonary endothelial cell barrier enhancement by sphingosine 1-phosphate: roles for cortactin and myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24692–24700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313969200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumer Y, Drenckhahn D, Waschke J. cAMP induced Rac 1-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization in microvascular endothelium. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:765–778. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0422-y. doi:10.1007/s00418-008-0422-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JF, Ozaki H, Zhan X, Wang E, Hla T, Lee MJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling regulates lamellipodia localization of cortactin complexes in endothelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;126:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s00418-006-0143-z. doi:10.1007/s00418-006-0143-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He P, Zeng M, Curry FE. Dominant role of cAMP in regulation of microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1124–H1133. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birukova AA, Zagranichnaya T, Fu P, Alekseeva E, Chen W, Jacobson JR, et al. Prostaglandins PGE(2) and PGI(2) promote endothelial barrier enhancement via PKA- and Epac1/Rap1-dependent Rac activation. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2504–2520. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.036. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlegel N, Waschke J. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein: crucial for activation of Rac1 in endothelial barrier maintenance. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:1–3. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comerford KM, Lawrence DW, Synnestvedt K, Levi BP, Colgan SP. Role of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein in PKA-induced changes in endothelial junctional permeability. FASEB J. 2002;16:583–585. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0739fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birukova AA, Alekseeva E, Cokic I, Turner CE, Birukov KG. Cross talk between paxillin and Rac is critical for mediation of barrier-protective effects by oxidized phospholipids. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:L593–L602. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90257.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu M, Waters CL, Hu C, Wysolmerski RB, Vincent PA, Minnear FL. Sphingosine 1-phosphate rapidly increases endothelial barrier function independently of VE-cadherin but requires cell spreading and Rho kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1309–C1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00014.2007. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00014.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee MJ, Thangada S, Claffey KP, Ancellin N, Liu CH, Kluk M, et al. Vascular endothelial cell adherens junction assembly and morphogenesis induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Cell. 1999;99:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81661-x. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81661-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta D, Konstantoulaki M, Ahmmed GU, Malik AB. Sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ mediates rac activation and adherens junction assembly in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17320–17328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411674200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M411674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregg D, Rauscher FM, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Rac regulates cardiovascular superoxide through diverse molecular interactions: more than a binary GTP switch. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C723–C734. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00230.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Wetering S, van Buul JD, Quik S, Mul FP, Anthony EC, ten Klooster JP, et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate Rac-induced loss of cell-cell adhesion in primary human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1837–1846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.9.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.