Abstract

An otherwise healthy 27-year-old woman presented with complaints of sudden painless blurred vision in the right eye for one week. On examination, visual acuity was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/20 in left eye. Fundus examination OS was normal, but OD demonstrated an elevated, opaque, yellowish parapapillary choroidal lesion with grayish membrane associated with minimal subretinal fluid, suggestive of a choroidal neovascular membrane in the center. B-scan ultrasonography revealed findings consistent with a choroidal osteoma. Fundus fluorescein angiography of the right eye revealed a relatively well defined area of hyperfluorescence that increased in size and intensity in the later phases, suggestive of active extrafoveal choroidal neovascular membrane. Optical coherence tomography confirmed the extrafoveal choroidal neovascular membrane with subfoveal fluid. She was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab OD. At the two-week visit, vision OD improved to 20/20. Fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography revealed a resolved choroidal neovascular membrane. Intravitreal bevacizumab may be an effective alternative in the management of choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to choroidal osteoma.

Keywords: osteoma, choroidal neovascular membrane, optical coherence tomography, bevacizumab

Introduction

The term ‘choroidal osteoma’ was coined by Gass in 1978 when he described four healthy young women with characteristic ophthalmoscopic findings of slightly elevated, yellowish, juxtapapillary, choroidal tumor with sharp geographic borders.1 The majority of patients with choroidal osteoma maintain good vision. In a follow-up study of 36 patients, the probability of loss of visual acuity (20/200 or worse) was more than 50% by 10 years.2 These tumors demonstrate evidence of bone formation in the choroid, and are believed to be choristomatous in origin.3 Choroidal neovascularization is the most frequent cause of visual loss in choroidal osteoma, with more than half of patients expected to develop choroidal neovascularization.3,4

Case report

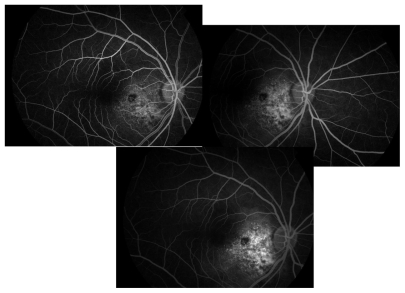

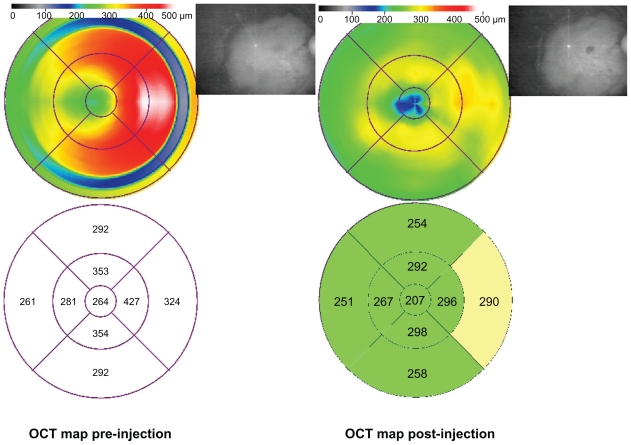

A 27-year-old female presented complaining of blurred vision in the right eye for one week. Her past ocular, medical, and family histories were noncontributory. On examination, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/30 N6 in the right eye and 20/20 N6 in the left eye. Her intraocular pressure was 11 mmHg in the right eye and 13 mmHg in the left eye. Her anterior segment examination in both eyes and fundus examination of the left eye were unremarkable. Ophthalmoscopic examination in the right eye showed a yellowish lesion on the posterior pole of about 5 mm × 5 mm in size (Figure 1). It was smooth on the surface with slight elevation. In the center of the lesion, subretinal hemorrhage of a fine dot size was noted. Fundus fluorescein angiography showed early patchy hyperfluorescence with late staining of the lesion. In the center of the lesion, and about one disc diameter nasal to the foveal avascular zone, early lacy hyperfluorescence (Figure 2) leaking in the late phase was noted, indicative of classic choroidal neovascular membrane, while the left eye showed an angiogram within normal limits. There was also an area of blocked fluorescence corresponding to the hemorrhage seen clinically. The B-scan showed very high reflectivity on the surface, with shadowing behind because of the presence of calcium in the leion (Figure 2). Optical coherence tomography confirmed a choroidal neovascular complex with subretinal fluid extending to the fovea (Figure 1). A diagnosis of osteoma with choroidal neovascular membrane was made. The patient underwent intravitreal bevacizumab injection (1.25 mg in 0.05 mL) for the choroidal neovascular membrane. It showed regression at one week follow-up, with resolution of subretinal hemorrhage and no fluid on optical coherence tomography (Figure 3) and no leakage on fluorescein angiography (Figure 4). The lesion remained stable at monthly follow-up at six months, with a final visual acuity of 20/20 N6 at the last visit. OCT maps are shown in Figure 5.

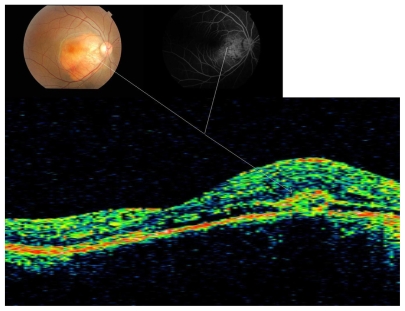

Figure 1.

Fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography showing corresponding location of choroidal neovascular membrane associated with osteoma in right eye.

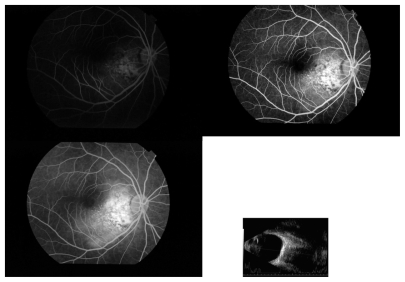

Figure 2.

Fluorescein angiography of right eye showing early lacy hyperfluorescence of choroidal neovascular membrane with later leakage, and B-scan (80 dB) showing corresponding shadowing due to osteoma.

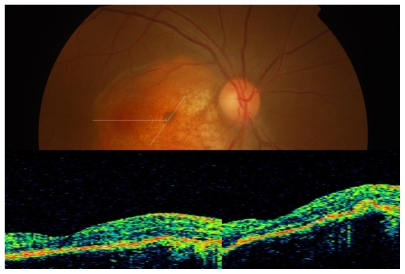

Figure 3.

Absence of subfoveal fluid on optical coherence tomography with regressed choroidal neovascular membrane.

Figure 4.

Fluorescein angiography showing regressed choroidal neovascular membrane with no leakage (early, middle, and late phase in the clockwise direction).

Figure 5.

OCT maps comparison showing reduction in thickness.

Discussion

Owing to lack of pigment in the tumor and atrophy of overlying retinal pigment epithelium, laser photocoagulation has limited efficacy (25%) in the treatment of choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma.5 Intravitreal bevacizumab is independent of the intrinsic pigmentation and has the advantage of sparing the overlying retina. Despite the patient having an extrafoveal choroidal neovascular membrane, we preferred intravitreal bevacizumab over laser. Encouraged by the results of antivascular endothelial growth factor for choroidal neovascular membrane in choroidal osteoma reported by Ahmadieh et al6 and Narayanan et al,7 we administered intravitreal bevacizumab and achieved complete regression of choroidal neovascularization. Because the visual acuity was 20/30 with minimal subfoveal fluid, and there was concern regarding the possibility of extension of the choroidal neovascular membrane into the foveal region, we kept the patient under close follow-up during the regression period.

There are case reports of treatment of choroidal neovascular membrane associated with choroidal osteomas with photodynamic therapy and ranibizumab with good efficacy, but cost effectiveness is a constraint, also the choroidal neovascular membranes noted in the literature are on the edge of choroidal osteoma.8,9 Our case illustrates an atypical location of choroidal neovascularization secondary to a choroidal osteoma that was successfully treated with intravitreal bevacizumab which is a very cost-effective treatment modality when compared with others.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr Vandana Dwivedi for her ideas, editing, and completing this paper.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Gass JD, Guerry RK, Jack RL, Harris G. Choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:428–435. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910050204002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shields CL, Shields JA, Augsburger JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;33:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aylward GW, Chang TS, Pautler SE, Gass JD. A long-term follow-up of choroidal osteoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1337–1341. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.10.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadrmas EF, Weiter JJ. Choroidal osteoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1997;37:171–182. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199703740-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grand MG, Burgess DB, Singerman LJ, Ramsey J. Choroidal osteoma. Treatment of associated subretinal neovascular membranes. Retina. 1984;4:84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadieh H, Vafi N. Dramatic response of choroidal neovascularization associated with choroidal osteoma to the intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:1731–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan R, Shah VA. Intravitreal bevacizumab in the management of choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:466–468. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shields CL, Materin MA, Mehta S, Foxman BT, Shields JA. Regression of extrafoveal choroidal osteoma following photodynamic therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:135–137. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song MH, Roh YJ. Intravitreal ranibizumab in a patient with choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroidal osteoma. Eye. 2009;23:1745–1746. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]