Summary

Neuronal Src (n-Src) is an alternative isoform of Src kinase containing a 6-amino acid insert in the SH3 domain that is highly expressed in neurons of the central nervous system (CNS). To investigate the function of n-Src, wild-type n-Src, constitutively active n-Src in which the C-tail tyrosine 535 was mutated to phenylalanine (n-Src/Y535F) and inactive n-Src in which the lysine 303 was mutated to arginine in addition to the mutation of Y535F (n-Src/K303R/Y535F), were expressed and purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. We found that all three types of n-Src constructs expressed at very high yields (~500 mg/L) at 37°C, but formed inclusion bodies. In the presence of 8 M urea these proteins could be solubilized, purified under denaturing conditions, and subsequently refolded in the presence of arginine (0.5 M). These Src proteins were enzymatically active except for the n-Src/K303R/Y535F mutant. n-Src proteins expressed at 18°C were soluble, albeit at lower yields (~10 – 20 mg/L). The lowest yields were for n-Src/Y535F (~10 mg/L) and the highest for n-Src/K303R/Y535F (~20 mg/L). We characterized the purified n-Src proteins expressed at 18°C. We found that altering n-Src enzyme activity either pharmacologically (e.g., application of ATP or a Src inhibitor) or genetically (mutation of Y535 or K303) was consistently associated with changes in n-Src stability: an increase in n-Src activity was coupled with a decrease in n-Src stability and vice versa. These findings, therefore, indicate that n-Src activity and stability are interdependent. Finally, the successful production of functionally active n-Src in this study indicates that the bacterial expression system may be a useful protein source in future investigations of n-Src regulation and function.

Keywords: Neuronal Src, Denaturation, Unfolding, Stability, Kinase Activity

INTRODUCTION

Src family kinases (SFKs) are highly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and are found to play important roles in the regulation of neural development and synaptic transmission [1–3]. Src is the best characterized kinase of the SFKs and has become an important target for the development of therapeutic approaches to many diseases. Three types of Src kinases have been identified: cellular Src (c-Src), viral Src (v-Src) and neuronal Src (n-Src) [4–6]. n-Src is expressed as the dominant form of Src in the developing brain [4,5,7]. C-terminal Src kinase (Csk) is also highly expressed in the embryonic brain, followed by a decrease in expression as the brain matures [4,8,9]. Csk specifically phosphorylates the C-tail tyrosine of SFKs (e.g., Y527 in chicken c-Src) and thereby acts as an endogenous depressor of SFKs [4,8,9]. It has been found that with a decrease in Csk expression the activity of Fyn (a member of SFKs) but not Src, is enhanced [7]. Although the activity of n-Src expressed in yeast can be down-regulated by Csk co-expression, n-Src showed much higher activity than c-Src, even in the repressed form [7]. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, activates SFKs via SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions. Endogenous FAK expressed in neurons binds specifically to the SH3 domain of c-Src but not n-Src [10]. These findings imply that n-Src may behave differently when compared to c-Src in the regulation of development and function of the CNS. Compared with other SFKs, high flexibility is found in the n-Src loop which has a unique conformation stabilized by the establishment of several intra-molecular hydrogen bonds [11]. The expression of n-Src is temporally augmented at the onset of neural differentiation, with constitutive activation of n-Src in vivo resulting in aberrant dendritic morphogenesis in mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells [12]. Most of the current knowledge regarding the structure and function of Src is obtained from well conducted investigations of c-Src and/or v-Src [3–5,13,14]. n-Src however remains largely unstudied. In the present study we expressed and purified wild-type, constitutively active and inactive n-Src proteins, and characterized their regulation in vitro.

Methods

n-Src protein expression and purification

cDNAs encoding full length mouse wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F, n-Src/K303R/Y535F or n-Src/K303A/Y535F confirmed by sequencing, were cloned into the pET15b vector and subsequently transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. To determine the optimal expression conditions, 20 mL cultures of N-terminal His6-tagged wild-type n-Src were grown in LB (Luria-Bertani) medium supplemented with 100 mg/mL of ampicilin at 37°C until the optical density at wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) of the cultures reached 0.6. The temperature was then kept at 37 °C or adjusted to 4, 10, 18 or 25 °C. The protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 hours. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 7,500 g for 15 min at 4°C. Pellets resuspended in Buffer A (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 25 mM imidazole) containing 1 mM PMSF were lysed using a sonicator, and then centrifuged at 25,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. Yields of soluble n-Src protein were estimated by performing SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie Blue G250. We found that the highest yield of soluble n-Src protein was obtained from the expression at 18°C.

Using the modified Autoinduction™ protocol [15], large scale cultures (1 L) were grown in Terrific Broth medium supplemented with 100 mg/mL of ampicillin at 37 °C for 3 – 4 hrs followed by lowering the temperature to 18 °C for an additional 18 hours. Cells were then harvested, lysed and clarified as mentioned above. The supernatant loaded on a Chelating Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences) was washed with Buffer A, followed by protein elution with 500 mM imidazole. His tag was removed by incubation with thrombin for 4 hrs at 37°C. Purified proteins were then concentrated following extensive dialysis in buffer containing 30 mM phosphate and 30 mM NaCl (pH 7.0), and stored at −20°C under reducing conditions (1 mM DTT). Based on SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (see below), the purity of the proteins was estimated to be at least 95%. For the subsequent analyses, the concentration of n-Src and its mutants was obtained using absorbance at 280nm and an extinction coefficient of 84,270 for wild-type n-Src and 82,780 M−1cm−1 for its mutants as calculated using ExPASy ProtParam tool (http://expasy.org/tools/protparam.html).

SDS-PAGE and trypsin digestion

Purified n-Src proteins were separated and stained on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel. The bands corresponding to each n-Src protein were excised from the gel and washed with 200 μL of 50% acetonitrile and 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Trypsin Profile IGD Kit, Sigma Aldrich). Gel slices were then dehydrated in 100% acetonitrile and dried. Gel slices were rehydrated and digested with 20 μL (0.4 μg) of reagent grade trypsin (Sigma Aldrich) and 50 μL of Trypsin Reaction Buffer at 37°C for 15 hrs. Peptides were extracted with 50% acetonitrile and 5% trifluroacetic acid. Extracts were dried under vacuum at room temperature and reconstituted in 3 μl of 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluroacetic acid. Following a 4 hr, 37°C digest with trypsin, peptides were dissolved in 50% methanol, 0.1% acetic acid solution and infused at a flow rate of 200 nL/min with electrospray ionization (ESI) potential of 4.1 kV. The spectra were scanned for 20 min, using ESI linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ MS, Thermo Finnigan). Ion Max electrospray was used as the ESI ion source.

Immunoblotting and in vitro kinase activity assay

Proteins purified from BL21(DE3) cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Antibodies including anti-Src antibody (Millipore), anti-pY527 antibody (Cell Signaling), anti-pY416 antibody (Cell Signaling), and anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10, Upstate) were used.

A modified ELISA-based kinase assay (PTK101, Sigma) was performed to determine the kinase activity of the n-Src proteins, as recommended by the manufacturer. n-Src proteins were added into the tyrosine kinase reaction buffer containing excess Mg2+, Mn2+ and ATP in microtiter plates coated with poly-Glu-Tyr substrate. The phosphorylation reactions were stopped via the addition of the Src inhibitor PP2 at each time point as indicated. A horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine antibody was used to detect the phosphorylated substrate. A color reaction was induced by adding HRP substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) and stopped with 0.25 M sulfuric acid, followed by absorbance measurement at 490 nm with a spectrophotometer in a microplate ELISA reader (Benchmark, BioRad). Steady-state kinase activity assays for the three proteins were carried out at room temperature for 30 min.

Circular dichroism (CD) studies

Far-UV CD measurements were performed using a Jasco 810 spectropolarimeter with a PTC343 Peltier unit (Jasco, Inc.). Wavelength scans from 180 – 260 nm were collected at 0.2 mg/mL protein concentration, in 30 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). A quartz cuvette with a 0.1 cm pathlength (Hellma) was used. Spectra were collected at room temperature at a scan rate of 50 nm/min in 0.2 nm increments with a response time of 4 sec. Results from three independent scans (collected in triplicates) and three protein preparations were collected for each sample (and each buffer), averaged and corrected for absorption of the buffer. Spectral analyses were performed using software provided by the manufacturer (Jasco). The mean residue ellipticity, [Θ], was obtained as follows:

| (1) |

where Θ in the CD signal in millidegrees, l is the pathlength (in cm), c is the protein concentration (in M), and N is the number of amino acids [16]. Secondary structure deconvolution was performed using the CDPro software with a basis set for known secondary structure content of 29 proteins [17]. The secondary structure contents were calculated with the software CDPro from the three algorithms (SELCON3, CONTINL and CDSSTR).

Urea denaturation studies were performed by pre-equilibrating protein samples at concentrations from 0 M to 6.0 M for at least 2 hrs at room temperature. No difference in signals was observed between 2 and 24 hr-incubation, suggesting that the proteins were equilibrated at 2 hrs. Spectra were collected with the same parameters as with the native proteins described above. Data points at 218 nm were expressed as a fraction of the total molar ellipticity change to estimate the midpoint of irreversible unfolding.

Effects of temperature on protein structure were also investigated. Initially, full wavelength scans (180 – 260 nm) were collected in 5°C increments after a 5 min equilibration in the cell holder. Spectra were collected from 20 – 70°C as a function of heating rate (10, 15 and 20°C/hr) to determine the kinetics of unfolding. Unfolding was found to be independent of the heating rate (data not shown), and irreversible. For optimal signal-to-noise ratio, a heating rate of 15°C/hr was used. Total ellipticity change was the greatest at 208 nm, and this wavelength was selected for monitoring secondary structure loss upon thermal denaturation. Data were collected in 0.2°C increments between 20 and 70°C. At each 10°C increment, samples were equilibrated for 5 min and full scans were collected. Molar ellipticity at 208 nm was expressed as a fraction of the total molar ellipticity change and midpoints of unfolding were estimated.

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence was measured as described previously [18]. Fluorescence emission spectra of Src proteins at 1 μM were recorded at 25ºC in a temperature-controlled cuvette holder on a Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer (Varian Instruments). Buffers and samples were filtered through 0.22 μm filter to insure removal of any aggregates. Protein samples containing varying amounts of urea were excited at 295 nm. The emission spectra were collected from 304 to 500 nm. The baseline recording was done with buffer alone prior to every run. Integrated fluorescence for each spectrum was normalized to the highest value detected in the presence of 0 M urea concentration and plotted versus the denaturant concentration. The midpoints of unfolding for each protein were estimated from the plot.

Light scattering measurement

Effects of temperature on protein self-association were examined by using light scattering at an excitation/emission wavelength of 340 nm in a Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer (Varian Instruments) equipped with a Peltier temperature controller. Solutions containing 1 μM of Src proteins were heated at 15°C/hr in a 1 cm pathlength quartz cuvette with stirring. Responses at 340 nm were collected in triplicates for three samples of each protein. The normalized light scattering signal was plotted against the temperature, and midpoints were estimated.

Results

Recombinant n-Src proteins expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells

Bacterial were cultured using the Autoinduction protocol [15] at 37°C followed by expression of n-Src proteins at 18°C. We found that all three types of n-Src constructs expressed at very high yields (~500 mg/L) at 37°C, but formed inclusion bodies. The formation of inclusion bodies is frequently observed with expression of eukaryotic proteins in bacteria [19,20]. In the presence of 8 M urea these proteins could be solubilized, purified under denaturing conditions, and subsequently refolded in the presence of arginine (0.5 M). Urea denaturation studies by measuring intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence showed no changes in the fluorescence signal, even when 6 M urea was added to the protein. We thus concluded that these proteins were unsuitable for biophysical studies, most likely due to the presence of high concentration of arginine. However, we found that these Src proteins were enzymatically active with the exception of the n-Src/K303R/Y535F mutant (data not shown).

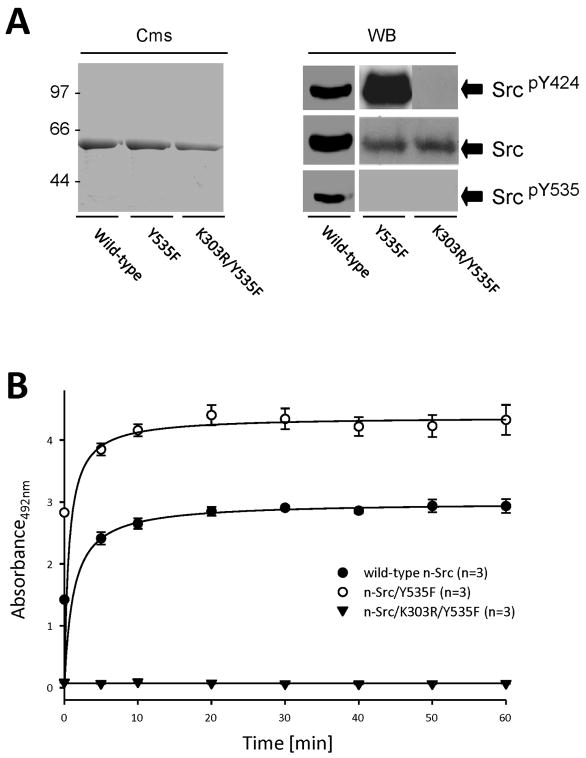

n-Src proteins expressed at 18°C were soluble, but the yields were lower (~10 – 20 mg/L, Table 1) when compared to expression at 37°C that produced inclusion bodies. The lowest yields were for n-Src/Y535F (~10 mg/L) and the highest for n-Src/K303R/Y535F (~20 mg/L) (Table 1). Figure 1A shows the Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and Western blot assays of purified n-Src proteins expressed at 18°C in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. Consistently, all these proteins were identified with an antibody recognizing Src C-tail (Upstate Biotechnology), wild-type and n-Src/Y535F were identified with an antibody recognizing phosphorylated tyrosine residue 424 corresponding to tyrosine 416 in chicken c-Src (Cell Signaling), but only wild-type n-Src was detected with an antibody recognizing phosphorylated tyrosine residue 535 corresponding to tyrosine 527 in chicken c-Src (Cell Signaling) (Fig. 1A). The sequence coverage of purified n-Src proteins was determined by analysis of tryptic peptides using tandem mass spectrometry.

Table 1.

Summary of vectors and purified protein yields

| Protein | N-terminal tag | C-terminal tag | Yield (mg/L) | Km (mg/mL) (mean ± SEM) | Vmax (nM/min) (mean ± SEM) | Purity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type n-Src | His-tag | None | 10 – 20 | 0.087 ± 0.012 | 72.51 ± 1.10 | >95% |

| n-Src/Y535F | His-tag | None | 10 | 0.04 ± 0.005 | 107.4 ± 1.28 | >95% |

| n-Src/K303R/Y535F | His-tag | None | 20 | - | ≈0 | >95% |

Figure 1. Purified n-Src proteins.

A: purified Src proteins expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) Cells. Cms: visualized with Coomassie G250. The numbers on the left of the gel indicate the molecular mass (kDa). WB: Western blotting with antibodies as indicated. SrcpY535 (corresponding to c-SrcpY527): probed with anti-pY527 antibody (Cell Signaling); SrcpY424 (corresponding to c-SrcpY416): probed with anti-pY416 antibody (Cell signaling). Src: an antibody recognizing the C-tail of Src (Upstate Biotechnology). B: the kinetics of kinase activity of purified n-Src proteins. Values in brackets indicate number of experimental repeats.

To confirm that n-Src proteins purified from E. coli were functionally active, we examined enzyme activity of purified n-Src proteins using a modified ELISA-based assay. Figure 1B shows kinetics of the enzyme activity detected in wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F and n-Src/K303R/Y535F. Compared with wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F showed twice the enzymatic activity, whereas the K303R mutant showed no activity (Fig. 1B). Km values of wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F were 0.087 ± 0.012 (mean ± SEM) and 0.04 ± 0.005 mg/mL, and Vmax 72.51 ± 1.10 and 107.4 ± 1.28 nM/min, which are similar to those found by others in c-Src purified from human platelets [21] and from bacteria [22]. Similarly to n-Src proteins expressed in mammalian cells [23], tyrosine phosphorylation at Y535 and/or Y424 was found in wild-type and constitutively active n-Src purified from E. coli, which may be produced via intra- and/or intermolecular mechanisms [24,25].

Effects of adding ATP on wild-type n-Src

To obtain insights for understanding how endogenous SFKs may be regulated, effects of addition of ATP (varied from 0 to 0.2 mM) on wild-type n-Src in vitro were examined (Fig. 2). We found that adding ATP increased the phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues 424 and 535 (Fig. 2A, B), and that the enzyme activity of wild-type n-Src increased in an ATP concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). This increase could not be found in the n-Src mutant in which K303 (corresponding to K295 in chicken c-Src) and Y535 were mutated to arginine and phenylalanine, respectively (n-Src/K303R/Y535F, Fig. 2C). With increases in temperature from 35 to 60°C, the light scattering of n-Src increased (Fig. 2D). The ATP addition shifted the light scattering of n-Src towards lower temperatures (Fig. 2D). The midpoints of light scattering were estimated at 50% of the total signal change. The midpoints of light scattering of Src incubated with 0, 0.02, 0.05 and 0.2 mM of ATP were estimated at 57, 54, 50 and 48°C, respectively.

Figure 2. Addition of ATP increases the enzyme activity and thermal unfolding of wild-type n-Src.

Gels in A and B were loaded with purified wild-type n-Src protein (which was pre-treated with λ-phosphatase) following addition of ATP at various concentrations as indicated. The filters were probed with antibodies against n-Src pY424 (A) or n-Src pY535 (B) and sequentially stripped and probed for total Src as indicated to the right of blots. Bar graphs show the ratios (means ± SEM calculated from 6 experiments) of the band intensities detected with antibodies against n-Src pY424 or pY535 versus those of total Src detected with an antibody recognizing the C-tail of Src, which were normalized to that in the presence of 0.1 mM ATP. C: summary data (means ± SEM from triplicate determinations of 2 separate experiments) showing the activity of recombinant wild-type and inactive n-Src following ATP addition at various concentrations as indicated for 30 min. D: summary data showing light scattering measurements of λ-phosphatase treated wild-type n-Src proteins on addition of ATP. The data represent mean of three determinations of three separate experiments. Solid lines in D represent the best fits of data with error bars indicating standard error.

A change in static light scattering intensity is directly proportional to an increase in turbidity of a protein solution, which may be induced by protein self-association and aggregation. Although mechanisms which may cause changes in the aggregation of n-Src and its mutants remain to be studied, the finding that addition of ATP increased light scattering signals (Fig. 2D) suggests a decrease in Src stability.

The characteristics of n-Src protein unfolding

We examined the secondary structure of wild-type n-Src, constitutively active n-Src (n-Src/Y535F), in which activity of the enzyme was increased when compared with wild-type n-Src (Fig. 1B), and inactive n-Src (n-Src/K303R/Y535F) proteins by measuring far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra. We found that wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F and n-Src/K303R/Y535F proteins in vitro had nearly identical far-UV CD features (Fig. 3A). The spectra of n-Src proteins showed a signal maximum at 195 nm and minima at 208 and 222 nm, indicating high helical content. The α-helix, β-sheet, turn and random coil contents in wild-type n-Src were calculated with CDPro at 40 ± 4% (mean ± SEM), 17 ± 1%, 26 ± 3% and 18 ± 5%, respectively (Table 2). No significant difference in the secondary structure content among the three n-Src proteins was found (Table 2). We then examined the secondary structure integrity of Src proteins in the presence of urea. No apparent change in CD spectra at 208 nm through 222 nm was noted for wild-type n-Src (Fig. 3B), n-Src/Y535F or n-Src/K303R/Y535F (data not shown) in urea concentrations up to 2.0 M. At 4.5 M urea, there were significant changes in CD spectra at 208 nm through 222 nm (Fig. 3B). Reduction in negative ellipticities at 208, 218, and 222 nm implied losses in α-helical and β-sheet conformations (Fig. 3B). We analyzed the CD data at 218 nm, where the greatest reduction of negative ellipticity was observed with increasing urea concentration (Fig. 3B). Figure 3C shows summarized data of molar ellipticity at 218 nm recorded from wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F, and n-Src/K303R/Y535F proteins. Apparent changes in molar ellipticity were observed in the presence of urea exceeding the concentration of 0.5 M. Increasing urea concentration to 1.5 M resulted in 20% and 10% changes in molar ellipticity of n-Src/Y535F and wild-type n-Src, respectively, while no change was detected in n-Src/K303R/Y535F (Fig. 3C). In the presence of 3.0 M urea, a half-maximal change in the ellipticity was found in n-Src/Y535F. Midpoints of denaturation were estimated at 50% change in total ellipticity at 2.8 M urea for n-Src/Y535F, 3.2 M urea for wild-type n-Src, and 3.8 M urea for n-Src/K303R/Y535F (Fig. 3C). When urea concentration was increased to 5.0 M, the ellipticity of all three proteins changed by 90% (Fig. 3C). No aggregation was observed in the presence of urea. After removal of urea from all three proteins, 50% signal recovery was observed, as compared with ellipticity at 218 nm of urea-free samples (data not shown).

Figure 3. Urea unfolding of wild-type and mutant n-Src.

A: CD spectra, each spectrum represents mean (± SEM) calculated from three scans. B: denaturation profile of wild-type n-Src with increasing urea concentration. C: assessment of molar ellipticity dependence on presence of urea monitored at 218 nm as a fraction of the total ellipticity change. Solid lines represent the best fit of data (mean ± SEM) calculated from three trials. D: summarized data (mean ± SEM) for global unfolding measured by fluorescence spectroscopy.

Table 2.

Secondary structure content (mean ± SEM)

| α-helix | β-sheet | turn | random coil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Src | 40 ± 4% | 17 ± 1% | 26 ± 3% | 18 ± 5% |

| n-Src/Y535F | 41 ± 4% | 15 ± 1% | 26 ± 2% | 18 ± 5% |

| n-Src/ K303R/Y535F | 41 ± 4% | 17 ± 2% | 26 ± 3% | 18 ± 5% |

The secondary structure contents were calculated with the software CDPro from the three algorithms (SELCON3, CONTINL and CDSSTR).

We then investigated urea effects on the tertiary structures of wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F and n-Src/K303R/Y535F using fluorescence spectroscopy. Upon excitation at 295 nm, the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra were collected from 304 to 500 nm. In their native state, all Src proteins had an emission wavelength maximum at 340 nm, indicating hydrophobic environments for tryptophans, and thus folded states [26,27]. At 6.0 M urea the maximum emission wavelength shifted to 355 nm as a result of unfolding and exposure of tryptophans to a polar solvent, which is consistent with previous reports [26,27]. Since only a two-state unfolding was observed for all three proteins, the observed changes in fluorescence emission intensities of Src’s nine tryptophans likely represent global unfolding of the proteins. Partial recovery in fluorescence signals could be detected after the removal of urea (data not shown). Integrated fluorescence intensities normalized to the total signal change recorded from the three proteins were plotted versus urea concentrations as summarized in Figure 3D. Apparent changes were observed in fluorescence signals at concentration higher than 0.5 M. When urea concentration was increased to 1.6 M, a 10% signal change was observed for n-Src/Y535F but not for wild-type n-Src or n-Src/K303R/Y535F. With a subsequent increase of urea concentration to 2.8 M, 50% signal reduction was found in n-Src/Y535F protein (Fig. 3D). Midpoints of urea denaturation were estimated at 50% amplitude of fluorescence signals at 2.8 M urea for n-Src/Y535F, 3.2 M urea for wild-type n-Src, and 3.6 M for n-Src/K303R/Y535F (Fig. 3D). At 5.0 M urea concentration, the fluorescence signals were diminished by 90% in all three proteins (Fig. 3D). These findings were consistent with those found in urea-induced CD spectral changes (Fig. 3B).

In contrast to urea, which triggered the greatest ellipticity change at 218 nm, increasing temperature resulted in the maximal signal change at 208 nm. Figure 4A shows summarized data of relative changes in molar ellipticity at 208 nm induced by temperature change. We found that when the temperature was increased from 20 to 35° C, the ellipticity changed by 20% in all three proteins (Fig. 4A). When the temperature was increased to 60°C, the ellipticity was diminished by 90% (Fig. 4A). The midpoints of thermal denaturation for wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F and n-Src/K303R/Y535F proteins were estimated at 44, 42 and 46°C, respectively.

Figure 4. Thermal unfolding of wild-type and mutant n-Src.

A: summarized CD data (mean ± SEM) showing relative changes in molar ellipticity at 208 nm (Scan rate: 200 nm/min; heating rate: 15°C/hr; only data points every 4°C were plotted). B: summarized fluorescence data (mean ± SEM) showing relative changes in light scattering.

To evaluate the role of protein self-association in the change of ellipticity induced by an increase in temperature, we measured light scattering of wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F and n-Src/K303R/Y535F at temperatures ranging from 20 to 70° C. Following completion of thermal unfolding, samples were equilibrated at room temperature for 20 minutes. Forty to 50% of fluorescence signals recorded at 20° C were recovered in all three Src proteins, as determined by fluorescence spectroscopy, indicating irreversible thermal unfolding.

In contrast to that found in the CD spectra at temperatures up to 35° C (Fig. 4A), increases in light scattering were less than 10% in all three Src proteins. The midpoints of light scattering in wild-type n-Src, n-Src/Y535F and n-Src/K303R/Y535F were 51, 48 and 54°C, respectively (Fig. 4B), which were significantly higher than the midpoints observed using CD spectroscopy at 208 nm (Fig. 4A). These findings suggested that temperature-induced CD spectral changes around 37° C were mainly due to protein unfolding, and not self-association. Both CD spectroscopy and light scattering showed that the increasing temperature had the greatest effect on n-Src/Y535F, and the smallest on n-Src/K303R/Y535F.

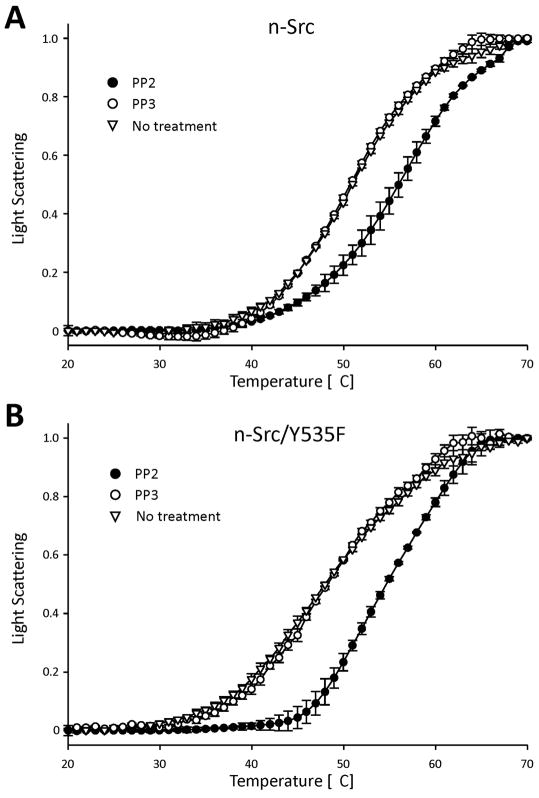

Effects of the SFK inhibitor PP2 on Src stability

We investigated effects of a pharmacological Src inhibitor, PP2 (4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine) [28,29] on light scattering of the three proteins under varying temperature conditions. Effects of PP3 (4-amino-7-phenylpyrazol[3,4-d]pyrimidine) [30], an inactive form of PP2 [30] were examined as a control. Wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F (2 μM) were each incubated with a 3-fold excess of PP2 (6 μM) for 1 hr. In the presence of PP2, both wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F showed a shift in their light scattering curves towards higher temperatures. The midpoints of light scattering of wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F increased from 51 and 48° C to 56 and 55° C, respectively. In contrast, PP3 application did not induce any change in light scattering when compared with control (no treatment, Fig. 5). These findings demonstrated that PP2 increased n-Src self-association.

Figure 5. Effects of the SFK inhibitor, PP2, on thermal unfolding.

Summarized fluorescence data (mean ± SEM) showing relative changes in light scattering measurement of n-Src (A) and n-Src/Y535F (B) induced by PP2 and PP3.

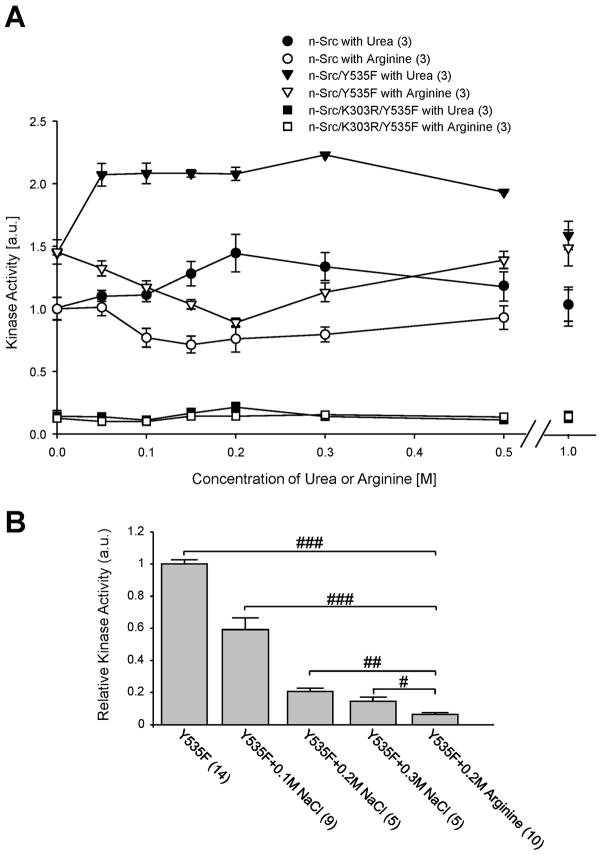

Effects of low-concentration urea or arginine on n-Src activity

To examine whether n-Src activity may be affected by altering protein unfolding, we investigated effects of adding low concentrations (0.5–1 M) of urea [31–33] or arginine [34–37] on n-Src activity, which produced no detectable change in the overall structure of the proteins. Figure 6A shows the kinase activities of these proteins measured in the absence or presence of urea or arginine. Presence of 0.05 M urea produced an increase in kinase activities of both wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F. Urea concentration-dependent increase in kinase activity was found up to the concentration of 0.3 M urea. Subsequent addition of urea diminished the enzyme activity (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the presence of urea produced no detectable change in the activity of n-Src/K303R/Y535F. Compared with increases in the kinase activity (14 ± 8%, 12 ± 5%, 30 ± 5%, n=3) of wild-type n-Src induced by urea at concentrations of 0.05, 0.1 and 0.15 M, significantly greater increases (P<0.05, Mann-Whitney test) in the kinase activity of n-Src/Y535F (43 ± 6%, 44 ± 5%, 44 ± 1%, n=3) were noted, indicating again a higher sensitivity of constitutively active Src (n-Src/Y535F) to urea.

Figure 6. Urea up-, but arginine down-regulates the activity of n-Src and n-Src/Y535F.

A: summary data (mean ± SEM) showing kinase activities, which were normalized to wild-type n-Src, in the presence of urea or arginine at various concentrations, as indicated. B: summary data showing the activity of n-Src/Y535F (Y535F) following addition of NaCl or arginine at various concentrations as indicated for 30 min. The activity was normalized to that of Y535F. Values in brackets indicate the number of experimental repeats. #, ## and ###: P<0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Conversely, the presence of up to 0.3 M arginine resulted in concentration-dependent reductions in kinase activities of wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F. At maximum, arginine inhibited the kinase activities of wild-type n-Src and n-Src/Y535F by 28 ± 7.0% (n=3) and 38 ± 3% (n=3), respectively. At arginine concentrations exceeding 0.3 M the enzyme activities were constant (Fig. 6A). In contrast, arginine had no effect on the activity of n-Src/K303R/Y535F. Furthermore, we compared kinase activity of the n-Src/Y535F protein when the ion concentration was changed by adding NaCl. Although increasing NaCl concentration reduced the n-Src activity, the effect produced by increasing NaCl was significantly smaller than that produced by adding the same concentration of arginine (Fig. 6B). Thus, we conclude that arginine may inhibit Src kinase through an ionic strength-independent mechanism.

Discussion

Previous work on Src kinase has made significant strides studying the role of Src in many different capacities [3–5,13,14]. However, these attempts have been limited by the difficulty of acquiring sufficient amounts of the protein. It has been proposed that expression of Src in vitro causes toxicity in the cells leading to cell death and thereby preventing adequate protein yields [4,5,13]. Our work demonstrated that while some toxicity may occur in BL21(DE3) cells expressing n-Src, the majority of the protein is sequestered in inclusion bodies. Furthermore, the protein can be extracted using urea and refolded in the presence of arginine into a functionally active protein. Additionally, slowing the expression by lowering the expression temperature to 18°C allows for the production of soluble n-Src protein at lower yields (10 – 20 mg/L). These proteins can nonetheless be purified and concentrated for biophysical studies. The ability to express and purify the full length n-Src proteins provide new avenues of research and allow for previously difficult structure/function studies to be performed.

Characterization of these in vitro expressed proteins demonstrated that with an increase in concentration of added ATP, the kinase activity and phosphorylation at both Y424 and Y535 of wild-type n-Src protein were enhanced. This finding suggests that both Y424 and Y535 in n-Src may be autophosphorylated in vitro. Wild-type n-Src can be a “mixture” of active and inactive n-Src. The activity measured in wild-type n-Src represented an integrated result depending upon ATP added. Unexpectedly, adding more ATP also shifted the light scattering of n-Src towards lower temperatures. This implies that the n-Src stability may be altered with changes in n-Src activity.

Urea- and temperature-induced unfolding show a trend in the stability of the secondary structure of Src proteins: n-Src/Y535F with the highest kinase activity was the most prone to unfolding and n-Src in which lysine 303 was mutated to arginine, producing the lowest kinase activity, was the most stable. Consistent with our findings, a previous study reported that v-Src protein expressed and purified from E. coli is less stable when compared with c-Src [38]. Crystallographic studies show that bindings of the SH2 domain to the phosphorylated C-tail, and/or SH3 domain to the SH2-kinase linker, lock Src in a closed conformation and thereby prevent the interaction of the Src kinase domain with its substrate [13,39,40]. However, recent detailed investigations also show that the SH2 domain may strongly interact with the kinase N-terminal lobe and position the kinase αC helix in an active configuration in active protein tyrosine kinases such as Fps [41]. This is stabilized by ligand binding to the SH2 domain [41]. We found that changes in Src enzyme activity produced either pharmacologically (e.g., application of ATP or a Src inhibitor) or genetically (e.g., mutation of Y535F, K303R or K303A in n-Src) are consistently associated with changes in Src stability. Our data showed that the Y535F mutation left n-Src in an open form providing increased activity and lower stability. However, the additional mutation of K303R which abolished n-Src activity while leaving it in the open form increased stability. These findings suggest an important link between the stability of n-Src and its subsequent activity. The mechanisms underlying the stability change and roles played by the “open form” (which may be induced by Y535F mutation) in this stability modification of Src, however, remain to be clarified.

Our data show that additional mutation at K303 (which is involved in a critical salt bridge with E310 required for catalytic activity of Src [13,39,40]) to arginine abrogated autophosphorylation of Src at position Y424, rendered n-Src inactive, depressed Src unfolding and reduced self-association. Inhibiting n-Src activity through application of PP2 reduced Src self-association in both constitutively active and wild-type n-Src. Therefore, the kinase domain may play a primary role in the control of Src unfolding and self-association.

Urea, acting as a destabilizing agent at low concentration, has been found to up-regulate adenylate kinase activity without changing the secondary or tertiary structure of the enzyme [33]. Although arginine binding may be in a limited capacity when compared to guanidinium hydrochloride [42], arginine can interact with most amino acid side chains and the peptide bonds, and thereby bind to the protein surface [34,35,43]. Concentrations of arginine from 0.1 – 0.5 M have been used to enhance protein stability and solubilization [34–37]. Arginine is also a part of the SH3 domain’s proline-rich ligand and is bound by an aspartate at position 101 (D101). Mutation of this aspartate in the Pro-rich ligand binding pocket inactivates the SH3 domain (D101N) [44,45]. Although the detailed mechanisms underlying the arginine effect on Src activity remain to be clarified, it is also possible that arginine binding to SH3 domain increases SH3 domain stability and decreases Src activity [44,45].

Using a bacterial expression system we were able to express and purify sufficient amounts of enzymatically functional n-Src proteins [21, 22] to perform detailed investigations into the functions of n-Src. We characterized the purified n-Src proteins expressed at 18°C and found that changes in n-Src enzyme activity were consistently associated with changes in n-Src stability. These data suggest that Src kinase activity may be stability-associated and that n-Src proteins purified from a bacterial expression system can be useful for detailed investigations of n-Src regulation and function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Piotr G. Fajer for critical comments on the manuscript. Plasmids of n-Src/K303R/Y535F and n-Src/Y535F were kindly provided by Dr. S. Hanks, Vanderbilt University [23]. We gratefully acknowledge the Biomedical Proteomics Laboratory at the College of Medicine, FSU, for the use of the mass spectrometry, UV/Vis spectroscopy and fluorescence instrumentation. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (R01 NS053567) to XMY.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hsueh RC, Scheuermann RH. Tyrosine kinase activation in the decision between growth, differentiation, and death responses initiated from the B cell antigen receptor. Adv Immunol. 2000;75:283–316. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(00)75007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu XM, Askalan R, Keil GJ, II, Salter MW. NMDA channel regulation by channel-associated protein tyrosine kinase Src. Science. 1997;275:674–678. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalia LV, Gingrich JR, Salter MW. Src in synaptic transmission and plasticity. Oncogene. 2004;23:8007–8016. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MT, Cooper JA. Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:121–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez R, Mathey-Prevot B, Bernards A, Baltimore D. Neuronal pp60c-src contains a six-amino acid insertion relative to its non-neuronal counterpart. Science. 1987;237:411–415. doi: 10.1126/science.2440106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inomata M, Takayama Y, Kiyama H, Nada S, Okada M, Nakagawa H. Regulation of Src family kinases in the developing rat brain: correlation with their regulator kinase, Csk. J Biochem. 1994;116:386–392. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nada S, Okada M, MacAuley A, Cooper JA, Nakagawa H. Cloning of a complementary DNA for a protein-tyrosine kinase that specifically phosphorylates a negative regulatory site of p60c-src. Nature. 1991;351:69–72. doi: 10.1038/351069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J, Weerapura M, Ali MK, Jackson MF, Li H, Lei G, Xue S, Kwan CL, Manolson MF, Yang K, MacDonald JF, Yu XM. Control of excitatory synaptic transmission by C-terminal Src kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:17503–17514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800917200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Messina S, Onofri F, Bongiorno-Borbone L, Giovedi S, Valtorta F, Girault JA, Benfenati F. Specific interactions of neuronal focal adhesion kinase isoforms with Src kinases and amphiphysin. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;84:253–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin-Garcia JM, Luque Irene, Mateo Pedro L, Ruiz-Sanz Javier, Cβmara-Artigas Ana. Crystallographic structure of the SH3 domain of the human c-Yes tyrosine kinase: Loop flexibility and amyloid aggregation. Febs Letters. 2007;581:1701–1706. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotani Takenori, Morone Nobuhiro, Yuasa Shigeki, Nada Shigeyuki, Okada Masato. Constitutive activation of neuronal Src causes aberrant dendritic morphogenesis in mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuroscience Research. 2007;57:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu W, Harrison SC, Eck MJ. Three-dimensional structure of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. Nature. 1997;385:595–602. doi: 10.1038/385595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingley E. Src family kinases: regulation of their activities, levels and identification of new pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabski Anthony, Mehler Mark, Drott Don. The Overnight Express Autoinduction System: High-density cell growth and protein expression while you sleep. Nat Meth. 2005;2:233–235. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woody RW. Theory of circular dichroism in proteins. In: Fasman GD, editor. Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of biomolecules. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. pp. 25–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sreerama N, Venyaminov SY, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: inclusion of denatured proteins with native proteins in the analysis. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:243–251. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rangachari V, Marin V, Bienkiewicz EA, Semavina M, Guerrero L, Love JF, Murphy JR, Logan TM. Sequence of ligand binding and structure change in the diphtheria toxin repressor upon activation by divalent transition metals. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5672–5682. doi: 10.1021/bi047825w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Groot NS, Ventura S. Effect of temperature on protein quality in bacterial inclusion bodies. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6471–6476. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh SM, Panda AK. Solubilization and refolding of bacterial inclusion body proteins. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;99:303–310. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Susa M, Teti A. Tyrosine kinase src inhibitors: potential therapeutic applications. Drug News Perspect. 2000;13:169–175. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2000.13.3.566664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemble DJ, Wang YH, Sun G. Bacterial expression and characterization of catalytic loop mutants of SRC protein tyrosine kinase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14749–14754. doi: 10.1021/bi061664+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polte TR, Hanks SK. Complexes of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Crk-associated substrate (p130(Cas)) are elevated in cytoskeleton-associated fractions following adhesion and Src transformation. Requirements for Src kinase activity and FAK proline-rich motifs. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5501–5509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osusky M, Taylor SJ, Shalloway D. Autophosphorylation of purified c-Src at its primary negative regulation site. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:25729–25732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jullien P, Bougeret C, Camoin L, Bodeus M, Durand H, Disanto JP, Fischer S, Benarous R. Tyr394 and Tyr505 are autophosphorylated in recombinant Lck protein-tyrosine kinase expressed in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:589–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duy C, Fitter J. How aggregation and conformational scrambling of unfolded states govern fluorescence emission spectra. Biophys J. 2006;90:3704–3711. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duy C, Fitter J. Thermostability of irreversible unfolding alpha-amylases analyzed by unfolding kinetics. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:37360–37365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karni R, Mizrachi S, Reiss-Sklan E, Gazit A, Livnah O, Levitzki A. The pp60c-Src inhibitor PP1 is non-competitive against ATP. FEBS Lett. 2003;537:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bain J, McLauchlan H, Elliott M, Cohen P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem J. 2003;371:199–204. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traxler P, Bold G, Frei J, Lang M, Lydon N, Mett H, Buchdunger E, Meyer T, Mueller M, Furet P. Use of a pharmacophore model for the design of EGF-R tyrosine kinase inhibitors: 4-(phenylamino)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidines. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3601–3616. doi: 10.1021/jm970124v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennion BJ, Daggett V. The molecular basis for the chemical denaturation of proteins by urea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5142–5147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930122100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanford C. Protein denaturation. Adv Protein Chem. 1968;23:121–282. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang HJ, Sheng XR, Pan XM, Zhou JM. Activation of adenylate kinase by denaturants is due to the increasing conformational flexibility at its active sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:382–386. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baynes BM, Wang DI, Trout BL. Role of arginine in the stabilization of proteins against aggregation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4919–4925. doi: 10.1021/bi047528r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsumoto K, Umetsu M, Kumagai I, Ejima D, Philo JS, Arakawa T. Role of arginine in protein refolding, solubilization, and purification. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:1301–1308. doi: 10.1021/bp0498793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SH, Carpenter JF, Chang BS, Randolph TW, Kim YS. Effects of solutes on solubilization and refolding of proteins from inclusion bodies with high hydrostatic pressure. Protein Sci. 2006;15:304–313. doi: 10.1110/ps.051813506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy KRC, Lilie H, Rudolph R, Lange C. L-Arginine increases the solubility of unfolded species of hen egg white lysozyme. Protein Sci. 2005;14:929–935. doi: 10.1110/ps.041085005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falsone SF, Leptihn S, Osterauer A, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. Oncogenic mutations reduce the stability of SRC kinase. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison SC. Variation on an Src-like theme. Cell. 2003;112:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sicheri F, Kuriyan J. Structures of Src-family tyrosine kinases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Filippakopoulos P, Kofler M, Hantschel O, Gish GD, Grebien F, Salah E, Neudecker P, Kay LE, Turk BE, Superti-Furga G, Pawson T, Knapp S. Structural coupling of SH2-kinase domains links Fes and Abl substrate recognition and kinase activation. Cell. 2008;134:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arakawa T, Ejima D, Tsumoto K, Obeyama N, Tanaka Y, Kita Y, Timasheff SN. Suppression of protein interactions by arginine: a proposed mechanism of the arginine effects. Biophys Chem. 2007;127:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woods AS. The mighty arginine, the stable quaternary amines, the powerful aromatics, and the aggressive phosphate: their role in the noncovalent minuet. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:478–484. doi: 10.1021/pr034091l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weng Z, Rickles RJ, Feng S, Richard S, Shaw AS, Schreiber SL, Brugge JS. Structure-function analysis of SH3 domains: SH3 binding specificity altered by single amino acid substitutions. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15:5627–5634. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarrine-Afsar A, Mittermaier A, Kay LE, Davidson AR. Protein stabilization by specific binding of guanidinium to a functional arginine-binding surface on an SH3 domain. Protein Sci. 2006;15:162–170. doi: 10.1110/ps.051829106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]