Abstract

Following exposure to traumatic events, approximately 19% of combat veterans develop posttraumatic stress disorder. One of the main symptoms of this mental illness is reexperiencing the trauma, which is commonly expressed in the form of chronic trauma-related nightmares. In these patients, nightmares can fragment sleep, decrease sleep quality, and even cause fear about going to sleep. One promising psychological treatment for chronic nightmares is imagery rehearsal therapy. Imagery rehearsal therapy presumes that nightmares are a learned behavior and that activating the visual imagery system may facilitate emotional processing of the trauma. This treatment involves deliberately rewriting a nightmare and mentally rehearsing images from the newly rescripted scenario while awake. Imagery rehearsal therapy has been found to reduce nightmares and associated distress. We present a case study demonstrating the use of imagery rehearsal therapy in a Vietnam-era veteran with posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic nightmares. Nightmares were considerably reduced and the quality of sleep greatly improved after treatment.

Citation:

Berlin KL; Means MK; Edinger JD. Nightmare reduction in a Vietnam veteran using imagery rehearsal therapy. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6(5):487-488.

Keywords: PTSD, nightmares, imagery

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental illness affecting approximately 19% of combat veterans1 following exposure to traumatic events. Symptoms include reexperiencing the trauma in a variety of ways (e.g., nightmares and intrusive thoughts), persistent avoidance of trauma-related stimuli (e.g., avoiding places, situations, or people associated with the trauma), and increased physiologic arousal (e.g., difficulty staying asleep).2 Approximately 60% of people with PTSD experience frequent nightmares, making nightmares one of the most common symptoms of the disorder.3

One promising nonpharmacologic treatment for nightmares is imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT).4 IRT is a cognitive-behavioral therapy conceptualizing chronic nightmares as a learned behavior that can be influenced via the mental imagery system during wakefulness. Although the precise therapeutic mechanism is unknown, IRT makes a number of assumptions, such as, nightmares are caused by trauma but sustained over time by habit; nightmares may serve an important purpose in processing emotions related to the trauma but, over time, may no longer be beneficial and instead disturb sleep; nightmares are a form of negative mental imagery; targeting mental imagery during wakefulness can thereby positively impact nightmares.5 This treatment involves guiding the patient to rewrite the nightmare into a new scenario by instructing the patient to change the nightmare in any way he or she chooses. The patient is taught imagery techniques to mentally rehearse the new altered scenario during the day several times per week. Consciously altering the original nightmare and rehearsing the new image are presumed to facilitate emotional processing of the trauma and provide the patient with a sense of control over the nightmares, reducing the frequency and distress associated with the nightmares. Empiric findings support the use of IRT in reducing nightmares in populations with and without PTSD and in maintaining this reduction over time.4,6

REPORT OF CASE

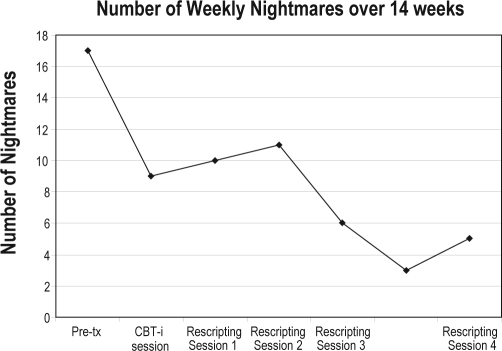

A 69-year-old male veteran with combat-related PTSD from 2 tours in Vietnam was treated for chronic nightmares and restless sleep. The veteran was taking ropinirole for restless legs syndrome. Polysomnography did not demonstrate sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, or other sleep pathology. Six sessions of psychotherapy (1: assessment, 2: cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, 3-6: IRT) were provided. Sessions were 1 hour and occurred every 3 to 4 weeks, depending on clinic availability. The veteran completed 6 weeks of sleep logs (3 weeks at baseline and 3 weeks after the cognitive-behavioral insomnia intervention). He also completed nightmares logs for 13 weeks (6 weeks prior to the first IRT session and 7 weeks throughout IRT treatment). Prior to treatment, the veteran averaged 17 nightmares per week (Figure 1) that were of strong intensity and caused him to kick and thrash in his sleep. He had resorted to sleeping in a recliner so that he did not fall and injure himself during these episodes. As evident in Figure 1, nightmare frequency decreased substantially during the baseline period, prior to the first IRT session. Although the precise cause of this reduction is unknown, it may represent night-to-night variability in the veteran's nightmare patterns, a change in life stressors or medications, a reduction in anxiety associated with beginning sleep therapy, or other unknown factors.

Figure 1.

Number of nightmares experienced by a 69-year-old Vietnam-era veteran treated with imagery rehearsal therapy

Pre-tx refers to pretreatment or baseline; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Content of the nightmares typically consisted of fighting with animals or being involved in combat situations. For example, the veteran rewrote a nightmare about being attacked by dogs to a scenario of befriending a dog. He rescripted a Vietnam combat nightmare to a scenario in which he was admiring the scenery in Vietnam. An excerpt from this story included: “As I looked out over the fields and hills, everything was so peaceful and beautiful. I felt very calm. I knew I was in a war zone, but I thought it was all the way up North, so I had pushed the war out of my mind.” He practiced visualization of the rescripted scenarios several times per week. Posttreatment, the veteran reported less nighttime awakening and improved quality of sleep. His nightmares were reduced to 5 nightmares per week (Figure 1). He further reported that he was able to sleep in his bed again because “fighting” in his sleep had ceased. The veteran reported that it was the best sleep he had experienced in 35 years. Treatment was terminated because the veteran was pleased with the outcome; he was satisfied with his sleep and felt confident he could continue using the IRT techniques on his own.

DISCUSSION

IRT is an effective psychological treatment for PTSD-related nightmares that can be conducted relatively quickly, inexpensively, and effectively on an outpatient basis. It is an attractive option for patients who want to manage their nightmares nonpharmacologically. This case study demonstrates the effective use of IRT in a Vietnam-era veteran suffering from repetitive chronic nightmares for more than 35 years.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Edinger has received research support from Philips Respironics and Helicor, Inc. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities of the Durham North Carolina VA Medical Center. The contents herein do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, Adams BG, Koenen KC, Marshall R. The psychological risks of Vietnam for U.S. veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science. 2006;313:979–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1128944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson LE. Nightmares. National Center for PTSD Fact Sheet on Nightmares. [Accessed on February 6, 2009]. Available at: http://www.ncptsd.va.gov.

- 4.Krakow B, Zedra A. Clinical management of chronic nightmares: imagery rehearsal therapy. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4:45–70. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0401_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krakow B, Hollifield M, Schrader R, et al. A controlled study of imagery rehearsal for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with PTSD: a preliminary report. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:589–609. doi: 10.1023/A:1007854015481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancee J, Spoormaker V, Krakow B, van der Bout J. A systematic review of cognitive-behavioral treatment for nightmares: toward a well-established treatment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:475–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]