Abstract

Tumor-specific cytotoxicity of drugs can be enhanced by targeting them to tumor receptors using tumor-specific ligands. Phage display offers a high-throughput approach to screen for the targeting ligands. We have successfully isolated phage fusion peptides selective and specific for PC3 prostate cancer cells. Also, we have demonstrated a novel approach of targeting liposomes through tumor-specific phage fusion coat proteins, exploiting the intrinsic properties of the phage coat protein as an integral membrane protein. Here we describe the production of Rhodamine-labeled liposomes as well as doxorubicin-loaded long circulating liposomes targeted to PC3 prostate tumor cells via PC-specific phage peptides, as an extension of our previous studies. Targeting of labeled liposomes was demonstrated using fluorescence microscopy as well as flow cytometry. Targeting of doxorubicin-loaded liposomes enhanced their cytotoxic effect against PC3 cells in vitro indicating a possible therapeutic advantage. The simplicity of the approach for generating targeted liposomes coupled with the ability to rapidly obtain tumor-specific phage fusion proteins via phage display may contribute to a combinatorial system for the production of targeted liposomal therapeutics for advanced stages of prostate tumor.

Keywords: Landscape phage, Major coat protein, Targeted liposomes, Prostate cancer, Doxil

Background

The narrow therapeutic windows of most anticancer chemotherapeutic agents represent a prohibitive factor in their clinical use, a case in point being the cardiac toxicity of doxorubicin. This results in a clinical threshold dose which cannot be exceeded even if it is required as in the case of tumor resistance to drugs. Conceptually, preferential delivery of drugs to pathologic sites should increase the local concentration of the therapeutic in the tumor milieu leading to a higher cytotoxic effect while simultaneously decreasing the side effects. One way to realize this concept is by targeting drugs to their sites of action by way of ligands specific for receptors either uniquely expressed or over-expressed in cancer cells.

The importance of targeting is underscored by the fact that amongst the new anti-neoplastic agents approved by the FDA since 2000, nearly 75% are targeted therapeutics (1). The benefits of targeting can be illustrated with numerous examples, an interesting one being the humanized anti-CD74 monoclonal antibody (hLL1 milatuzumab). This antibody has been used as an anticancer drug by itself, as a carrier for cytotoxic drugs and also as a navigating ligand for liposomes loaded with doxorubicin (2–4). A recent review has broadened the perspective of targeting ligands beyond antibodies by enumerating applications of Hunter-Killer peptides (HKPs), chimeric molecules consisting of a navigating moiety and a cytotoxic moiety, in medical conditions like cancer, obesity and arthritis (5–9).

Despite the success of these approaches, within the purview of targeting, if one considers the ‘payload’, the amount of drug reaching the target tissue, targeting of drug delivery systems will be seen to be more efficient in terms of the stoichiometric ratios of the targeting ligand to drug molecules. Apart from the increased numbers of drug molecules being delivered within a drug delivery vector, drug delivery systems capitalize on the unique tumor vasculature to achieve passive targeting (Enhanced Permeation and Retention effect) (10), provide protection for the drug from degradative mechanisms, favorably alter the pharmacokinetics of the drug and improve solubility of drugs with low solubility.

Liposomes have been the most successful drug delivery system used to date with the success mainly attributable to their biocompatibility. Liposomal formulations of doxorubicin (Doxil®) are being used in a variety of tumors. The clinical success and stability of the formulation has stimulated a number of research groups to attempt to improve its performance by grafting its surface with various targeting ligands to achieve active targeting. Torchilin et al developed a rapid method for attaching ligands containing primary amino groups to the distal ends of PEG chains grafted onto liposomes using p-nitrophenylcarbonyl-Polyethyleneglycol-1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (pNP-PEG-DOPE) (11). Another technique referred to as the ‘post insertion technique’ was developed by Ishida et al and involves transfer of ligand-coupled PEG molecules from micellar preparations directly into pre-formed liposomes (12). Comparison of binding efficacy and cytotoxicity of targeted liposomes prepared by the post-insertion technique with those prepared by conventional conjugation techniques showed no significant differences between the formulations but the ease associated with the post-insertion technique clearly made it ideal for large scale preparations as well as for combinatorial approaches (13).

An approach similar to that of the post-insertion approach has been developed in our laboratory capitalizing on the unique structural and chemical properties of the landscape phage fusion coat protein. Phage coat protein is an integral membrane protein and when separated from the phage assembly tends to insert spontaneously into lipid bilayers (14, 15). We exploited the ‘membranophilic’ nature of the coat protein to insert streptavidin-specific peptides fused to the N-terminus of the phage coat protein into liposomes. The resulting liposomes were then tested for streptavidin specificity in a functional test using streptavidin-conjugated colloidal gold particles, which demonstrated that the modified liposomes acquire streptavidin-targeting properties by virtue of the incorporated fusion proteins (16).

Following the proof-of-concept studies using the streptavidin model system, we used landscape phage libraries to select for landscape phage probes for PC3 prostate carcinoma cells (17). Fusion phage coat proteins bearing the tumor-specific peptides were then harvested from phage particles and inserted into liposomes using techniques described earlier (16). The orientation and efficiency of insertion of the coat protein units into liposomes were evaluated using western blot. In vitro targeting studies using fluorescence microscopy and FACS were used to demonstrate the PC3-avidity of the targeted liposomes. Furthermore, PC3-specific peptides were grafted onto Doxil and the impact of targeting was evaluated by comparing the cytotoxicities of different liposomal preparations against PC3 cells in vitro.

Methods

Cells

Cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). The PC3 (CRL-1435) cells were derived from the bone metastasis of a grade IV prostatic adenocarcinoma. HEK293 (CRL-1573) cells, derived from fetal kidney were used as controls in microscopy and fluorescence studies. Cells were grown as recommended by ATCC and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Phage coat protein

Selection of phage probes for PC3 cells has been previously described (17). Two phage fusion proteins harboring peptides DTDSHVNL (designated 8-3) and DVVYALSDD (designated 9-8) demonstrating high specificity and selectivity for PC3 cells were identified for use in current experiments. Phage coat protein from these PC3-targeting phages were isolated as described previously (16). Concentration of protein in samples was determined spectrophotometrically by use of the formulas, 1 A280=0.7 mg/mL for 8-3 phage protein and 1 A280=0.6 mg/ml for 9-8 phage protein, based on the molar extinction coefficients predicted by Protean software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI). Phage coat protein from a phage bearing an unrelated peptide, VPEGAFSS (termed 7b1) as well as coat protein from the wild type phage vector (f8-5) was isolated for use in the preparation of control liposomes.

Fluorescently labeled liposomes

Egg Phosphatidylcholine (ePC), 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine, 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-Glycero-3-(Phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) (Sodium Salt) (DPPG), 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-Trimethylammonium-Propane (Chloride Salt) (DOTAP), 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine-N-(Amino(Polyethylene Glycol 2000) (Ammonium Salt) (PEG2000-PE), 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphoethanolamine-N-(Lissamine Rhodamine B Sulfonyl) (Ammonium Salt) (Rho-PE), Cholesterol (98%) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). For preparation of liposomes, a lipid film was obtained from a mixture of ePC, cholesterol, DPPG, DOTAP, PEG2000-PE and Rho-PE in chloroform at a molar ratio (44:30:20:2:3:1). The chloroform was evaporated on a Brinkmann Buchi R-220RW Rotary Evaporator (BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) and the film hydrated with an appropriate volume of 1x PBS. The crude liposome dispersion was extruded 20 times through polycarbonate filters (100 nm) using an Avanti Mini-Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). Size distribution was measured by dynamic light scattering using a Coulter N4 MD submicron particle analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) and zeta potentials were determined using a 90 PLUS particle size analyzer with a Zeta PALS system (Brookehaven Corp., Holtsville, NY). Following extrusion, liposomes were stored at 4°C until further experimental manipulation.

Phage protein-targeted labeled liposomes

Labeled liposomes were grafted with PC3-specific phage fusion proteins by incubating the liposomes with phage fusion protein solution (1% of lipids w/w) in 15 mM sodium cholate overnight at 37°C. Following incubation, sodium cholate in the formulation was removed by gradient dialysis steps in 10 mM sodium cholate, 5 mM sodium cholate and finally 1x PBS solutions. All dialysis steps were performed in a volume of 1 L.

Electron Microscopy of Liposome Preparations

Briefly, formvar/carbon-coated electron microscopic grids (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, California) were incubated with drops of targeted liposomes or non-modified liposomes for 20 minutes. The grids were then negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid containing 0.1% BSA as wetting agent and dried before being visualized by a Phillips transmission electron microscope (FEI Co.,Hillsboro Oregon).

Selectivity of PC3-targeted labeled liposomes

PC3 cells and HEK293 cells were grown to subconfluence in 25 cm2 cell culture flasks, collected by trypsinization and counted. Equal numbers of each cell line were then re-suspended in 1 ml of GIBCO™ Improved MEM Zn++ Option (Richter’s Modification) liquid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). CellTracker Green CMFDA (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) was then used to stain HEK293 cells using a 1:100 dilution of CellTracker Green CMFDA stock in sterile clear 1 × Hanks and then 1 μl of diluted dye added per 1 × 106 cells for 15 min at 37 °C. The cell suspension was pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in Improved MEM and incubated for 15 min followed by centrifugation. The pellet was washed 3 times with Improved MEM. Following labeling, equal numbers of PC3 cells and labeled HEK293 cells were mixed together. The cell mixtures in different tubes were then treated with either PC-specific liposomes or different control liposomes for 90 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed twice in Improved MEM followed by reconstitution in 500 μl of the same media. The preparations were then used for fluorescence microscopy as well as flow cytometry.

For microscopy, aliquots of the cell mixtures were applied to microscopic slides (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), covered with coverslips (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) and visualized with a Cytoviva® microscope system (Cytoviva, Auburn, AL) using FITC, Texas Red and triple band pass (for DAPI, FITC and Texas Red) filters. Images were captured using DAGE® software.

For testing by flow cytometry, samples were further filtered through a 50 μm CellTrics filter (Partec GmbH, Germany) before being analyzed on a MoFlo flow cytometer in the green (530 ± 20 nm) and red (700 ± 15 nm) channels. The data was analyzed using Summit 4.3 software (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Data derived from three separate experiments were analyzed using ANOVA and significance was demonstrated by pair-wise comparisons of means using Tukey’s HSD test.

Phage fusion protein-targeted Doxil

Doxil liposomes (Ortho Biotech, Bedford, OH) were grafted with PC3-specific phage fusion proteins or with control phage proteins in a procedure similar to that outlined above. Size distribution and Zeta potentials of liposomal preparations were determined as described above. Doxil-entrapped doxorubicin was determined by monitoring absorbance at 492 nm using a Tecan SpectraFluor Plus plate reader (Tecan Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA) after treating the samples with an equal volume of 1% v/v TritonX-100.

Analysis of fusion major coat protein in liposomal preparations

Liposome preparations in 0.5 X PBS, 50 mM Tris HCl and 5 mM CaCl2 were incubated with 50 μg/ml of proteinase K (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by addition of phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, final concentration 5 mM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Samples were then mixed with an equal volume of tricine sample buffer (8% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 24% glycerol, 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 4% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% Brilliant blue G, 2x) (Jule Inc., Milford, Connecticut) and heated at 95ºC for 40 min. Denatured samples (10 μl) were loaded onto 16% Non-gradient Tris-Tricine gels (Jule Inc., Milford, Connecticut). Electrophoresis was carried out for 30 min at 100V. Proteins in the gel were transferred to an Immobilin-P PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts) and resulting blots probed with either anti-fd IgG (0.594 ng/ml) for detection of N-terminus of peptide or affinity purified anti-pVIII C terminus IgG antibody (3.6 ng/ml) (SigmaGenosys, The Woodlands, Texas) for C-terminus detection. This was followed by incubation with biotinylated-SP-conjugated Affinitipure goat antirabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, Westgrove, Philadelphia) and finally with NeutraAvidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois) before being visualized using a chemiluminescent substrate solution (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois).

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of various preparations of the liposomal doxorubicin against PC3 cells was investigated using a ready-to-use CellTiter 96® Aqeous One solution of MTS (Promega, Madison, WI) following the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. Liposomal formulations with doxorubicin concentration of up to 200 μg/ml dispersed in cell culture media were added to PC3 cells grown in 96-well cell culture plates to about 60% confluence in three replicates and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 h. Following the incubation, the cells were washed five times with the cell culture media and treated with 20 μl of CellTiter 96® Aqeous One solution in 80 μl of cell culture media and incubated further at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1–2 h. The cell survival rate was estimated by measuring the absorbance of the MTS degradation product at 492 nm using the Tecan SpectraFluor Plus plate reader (Tecan Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA). Data was analyzed using ANOVA and significance was demonstrated by pair-wise comparisons of the means using Tukey’s HSD test.

Results

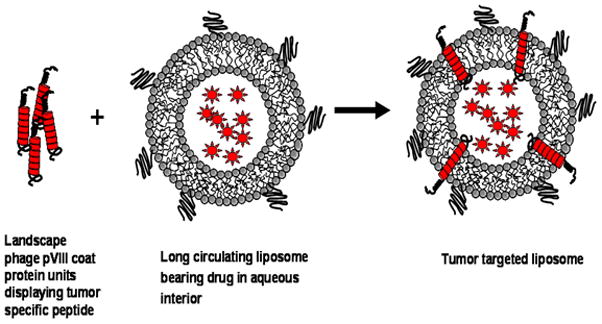

We had earlier demonstrated the feasibility of the using target-specific phage fusion proteins as the navigating module of liposomes (16). The success of this approach has led to proof-of-concept studies with the preparation of tumor-specific liposomes. Using standard phage display protocols already described (17, 18) we were able to identify selective and specific phage probes (termed 8-3 and 9-8) for PC3 prostate carcinoma cells from landscape phage libraries. The phage coat proteins from these phages including the N-terminal target-specific peptides were isolated and purified before being incorporated into Rhodamine-labeled liposomes as well as Doxil liposomes (Figure 1). Addition of the targeting module to liposomes was intended to enhance their successful association with target PC3 cells enabling higher cytotoxic effect in vitro against PC3 cells.

Figure 1.

Model of drug-loaded liposome targeted by the phage pVIII fusion coat protein created by exploiting the amphiphilic nature of the phage coat protein. The hydrophobic helix of the pVIII spans the lipid bilayer anchoring it such that the N-terminal tumor-specific peptide is displayed on the surface of the carrier particles. The drug molecules are pictured as spiked circles within the liposomes.

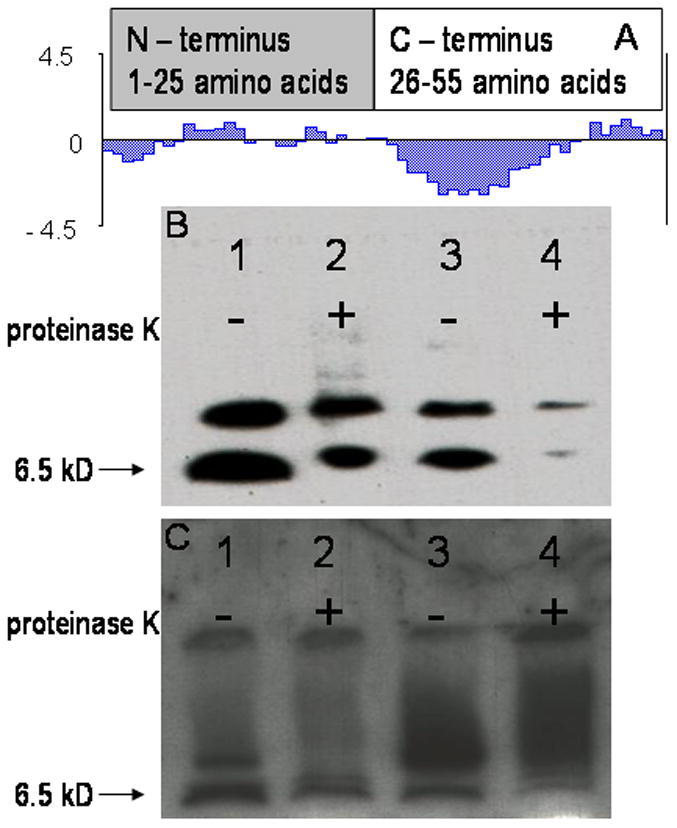

Preparation of labeled PC3-specific liposomes

The principle underlying the assembly of liposomes targeted with phage fusion protein depends on creation of conditions conducive for the transfer of phage coat protein units from detergent micelles into available lipid bilayers. We used a 15 mM cholate solution to achieve this objective. Once the coat protein unit was stabilized in lipid bilayers, the cholate was gradually removed from the mixture to further stabilize the liposomes. Rhodamine-labeled liposomes navigating to PC3 prostate carcinoma cells were prepared via the incorporation of PC3-specific phage fusion proteins using this technique. Liposomes modified with an unrelated phage fusion protein (VPEGAFSS termed 7b1) or with coat protein from wild type vector phage (f8-5) were also prepared as controls. Surface grafting with the phage coat protein did not alter the architecture of the liposomes as indicated by comparative size distribution (Supplementary figure 1), zeta potential data for unmodified (−43.46 ±2.17) and modified (−39.48 ± 3.71) preparations and electron microscopy (Supplementary figure 2). The presence and orientation of the PC3-specific phage coat proteins in liposomes was determined by western blotting and representative results from two preparations are presented in Figure 2B and 2C. Treatment with proteinase K hydrolyzes the exposed part of the phage fusion protein external to the lipid bilayer thereby precluding its subsequent detection with the respective antibody. Thus, with the antibody specific for the N-terminus of phage coat protein, a decrease in signal after treatment with proteinase K was observed, the decrease being almost complete with 8-3 liposomes, whereas with 9-8 liposomes it is ~50% of the original as quantified by densitometry analysis using the Image J software. The bands observed above the bands of interest are likely aggregated forms of the coat protein and have been previously shown to occur (15). When the blots were probed with antibody specific for the C-terminus, the 8-3 preparation demonstrated little to no decrease in the signal whereas some decrease was observed in the 9-8 preparation. It should be noted that the hydrophobicity of the remaining C-terminus may change its migration behavior after cleavage of the N-terminus causing an apparent reduction in the mobility (Figure 2C). Also, since the affinity of the C-terminus antibody is much lower than that of the N-terminus antibody, the samples were concentrated so that the amount of protein that was loaded was approximately 10 times higher for these experiments. These results imply that the N-terminus is exposed at the liposomal surface albeit in different proportions in different targeted preparations. Similar results were obtained when probing the topology of the coat protein in phage fusion protein modified Doxil (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of phage fusion protein-modified liposomal preparations to determine presence and topology of phage fusion protein. (A) Hydropathy plot of phage coat protein showing an amphiphilic N-terminus and a more intensely hydrophobic C-terminus. The molecular weight of the coat protein is 6.5 kD. Liposomal preparations were treated with proteinase K and then probed with antibodies specific for either N-terminus (B) or C-terminus (C) of the phage coat protein. Removal of amphiphilic N-terminus by proteinase K cleavage may alter migration of the remaining hydrophobic C-terminal coat protein segment leading to the appearance of smears in the blots probed with the C-terminus antibody. Lane 1 – 9-8 liposomal preparation untreated with proteinase K, lane 2 – 9-8 liposomal preparation treated with proteinase K. A ~50% decrease in signal is observed implying that approximately half of the coat protein units had the N-terminus out orientation, lane 3 – 8-3 liposomal preparation untreated with proteinase K, lane 4 – 8-3 liposomal preparation treated with proteinase K. The signal decreases nearly completely implying that nearly all of the coat protein units had the N-terminus out orientation.

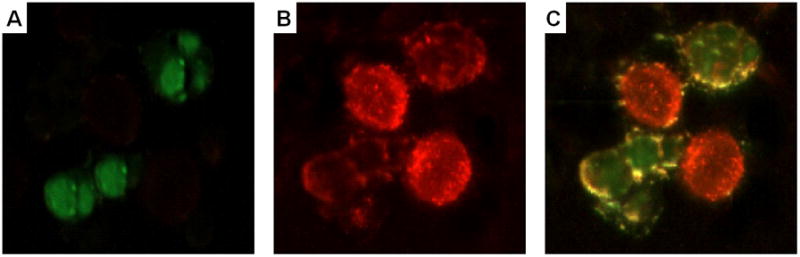

Targeting of labeled PC3-specific liposomes

The targeting efficiency of PC3-specific liposomes was evaluated based on their preferential association with PC3 cells in a mixture of target and control cells. Control HEK293 cells, a non-transformed epithelial cell line, were labeled with a vital dye, CellTracker Green CMFDA to allow visualization by microscopy and separation as a discrete population by flow cytometry, whereas target cells were unlabeled. In principle, selective labeling of PC3 cells by targeted liposomes would promote visualization and identification of the PC3 cells. In fluorescence microscopy, the same field was observed under three different filters. Under the FITC filter, only control HEK293 cells stained green with the vital dye were visible (Figure 3A) whereas the same field under the Texas Red filter allowed detection of PC3 cells stained as a result of liposome binding (Figure 3B). Comparison of these two populations using a compound filter allowed discrimination between target PC3 cells and control HEK293 cells in the same field (Figure 3C). Targeted liposomes show an increased avidity for PC3 cells as substantiated by the intense staining of the PC3 cells. Non-specific staining of control cells by the targeted liposomes is observed but is relatively low and can be attributed to the affinity of liposomes to cell membranes.

Figure 3.

Cancer cell-specific association of PC3-targeted rhodamine-labeled liposomes. Fluorescent microscopy of a mixture of target PC3 cells and green vital dye-labeled control HEK293 cells treated with PC3-specific rhodamine-labeled liposomes. Selective association of red liposomes with PC3 cells enables their visualization under a red or a composite filter. Panels represent a representative field of observation under different filters; A –FITC filter, B –Texas Red filter, C – Triple band pass filter.

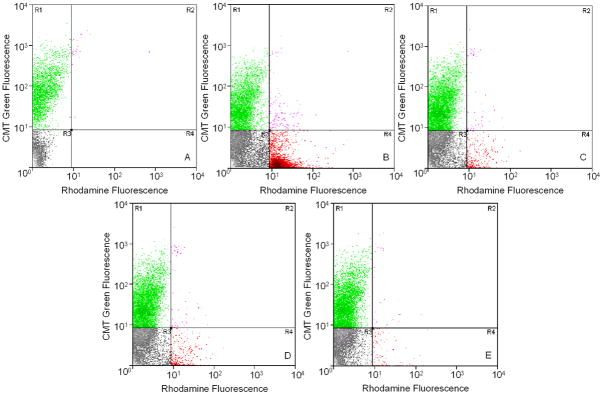

Flow cytometry resolved the mixed population of cells, prior to liposomal treatment, into two distinct populations based on the fluorescence staining of the HEK293 cells in the green channel (y-axis of dot-plots, Figure 4A) consisting of labeled control cells (R1) and unlabeled target cells (R3). Treatment with rhodamine-labeled liposomes resulted in the appearance of two new populations based on the fluorescence intensity in the red channel (x-axis of dot-plots, Figure 4B) including liposome-labeled PC3 cells (R4) and liposome-labeled HEK293 cells (R2). A predominant shift of target PC3 cells along the red channel was observed after treatment with PC3-specific liposomes (targeted by 8-3 peptide in this experiment) that was not detected with the other control liposomal formulations indicating the specific targeting by PC3-specific phage fusion protein on the liposome surface. Controls included liposomes modified with phage fusion protein bearing an unrelated peptide (Figure 4C), liposomes modified with phage coat protein from wild type phage (Figure 4D) and unmodified liposomes (Figure 4E). Similar results were obtained with liposomes targeted with the 9-8 peptide.

Figure 4.

Cancer cell-specific association of PC3-targeted rhodamine-labeled liposomes. Flow cytometric analysis of a mixture of unlabeled target PC3 cells and green-labeled control HEK293 cells without liposomal treatment differentiated into two distinct populations (A), based on the fluorescence intensity in the green channel (y-axis), consisting of labeled control cells (R1) and unlabeled target cells (R3). Treatment with targeted or control rhodamine-labeled liposomes resulted in the appearance of two new populations based on the fluorescence intensity in the red channel (x-axis) including liposome-labeled PC3 cells (R4) and liposome-labeled HEK293 cells (R2). A predominant shift of target PC3 cells along the red channel was observed after binding PC3-specific liposomes (B) that was not detected with other control liposomal formulations [liposomes targeted with unrelated phage peptide termed 7b1 (C), liposomes targeted with wild type phage coat protein (D) and untargeted liposomes (E)]. A representative experiment with liposomes modified with the 8-3 phage fusion protein is shown. Similar results were obtained with 9-8 PC3-specific phage fusion protein. Experiments were repeated thrice.

The relative proportions of target and control cells appearing in the regions R4 and R2 after treatment with PC3-specific or control liposomal preparations in three separate experiments were then used to obtain a quantitative measure termed Targeting Index (TI) according to the following formula;

Where,

TI – Targeting index

R4 – liposome labeled PC3 cells

R3+R4 – total number of PC3 cells

R2 – liposome labeled HEK293 cells

R1+R2 – total number of HEK293 cells

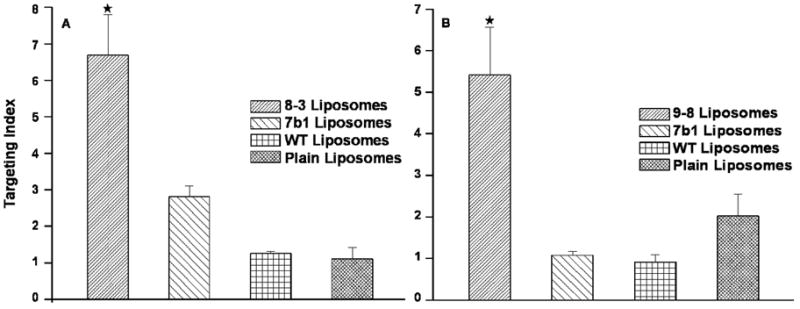

Liposomes targeted with cell-specific peptide showed a significant preference to associate with their cognate PC3 target cells over control cells (p<0.05) in this analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Quantitative expression of cancer cell specific association of targeted liposomes. Flow cytometry data (cell counts by region) was analyzed as outlined in the results to obtain a relative measure of the cell targeting abilities of liposomal preparations.

★ – p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference posthoc test

Preparation of doxorubicin-loaded phage fusion protein-targeted liposomes

Using the procedure described, we grafted Doxil with phage fusion proteins (8-3 and 9-8). Doxil modified with non-relevant phage fusion peptides specific for streptavidin (VPEGAFSS) as well phage coat protein from the wild type vector phage were also prepared as controls. Surface grafting with the phage coat protein did not affect architecture of the liposomes as indicated by the comparative size distribution and zeta potential data (data not shown). The presence of phage coat proteins in the liposomal preparations were determined by western blotting as described before (data not shown). The doxorubicin content of the liposomes decreased during ligand incorporation but the amount retained allowed a comparative estimation of their cytotoxic potential.

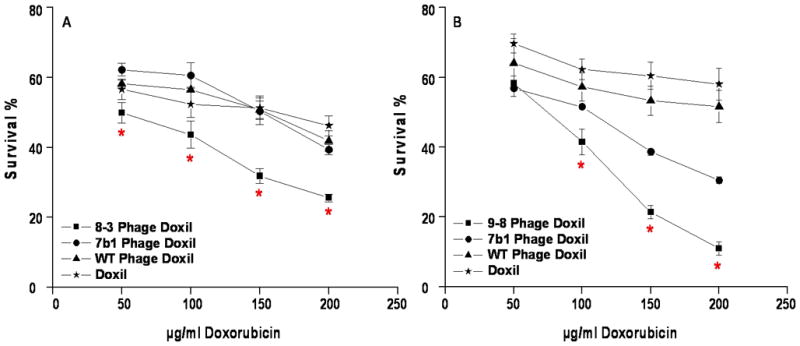

Cytotoxicity of doxorubicin-loaded phage fusion protein-targeted liposomes

We postulated that targeting liposomal preparations with tumor-specific peptides would enhance cytotoxicity of anticancer drugs. Accordingly, targeted and control liposome formulations, with equivalent concentrations of doxorubicin, were evaluated in an in vitro cytotoxicity assay. Doxil targeted with PC3-specific peptides demonstrated a significantly higher cell killing effect in comparison to the control liposomes with a dose-dependent pattern (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

In vitro cytotoxicity results of PC3-specific doxorubicin-loaded liposomal formulations. Doxil was grafted with PC3-specific phage fusion proteins (8-3 and 9-8) or control phage fusion proteins (7b1, an unrelated peptide or coat protein from wild type phage, WT) and incubated with PC3 cells for 48 h. The cytotoxicity of each preparation was expressed as percent survival compared to untreated cells which were considered to be 100%. A – 8-3 grafted Doxil, B – 9-8 grafted Doxil.

★ – p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honestly significant difference posthoc test

Discussion

Prostate cancer remains the most common neoplastic disease in the western hemisphere among men and is the second leading cause of mortality (19). Despite treatments like radical prostatectomy and androgen ablation, approximately 20% of cases proceed to an advanced hormone independent stage (20). This stage described as hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) was characterized by a lack of good treatment options until two multicenter phase III trials led to the approval of docetaxel as a standard treatment for HRPC (21). However, side effects arising from the vehicle, Tween 80 created a need for alternative methods to deliver this drug as well as a need to revisit the utility of targeting other available drugs.

Studies involving the active targeting of doxorubicin-loaded liposomes and Doxil in various prostate cancer models have provided very encouraging results (22–25). The results from these studies clearly indicate that targeting functions to increase the therapeutic performance of anticancer drugs. In addition, the use of targeted Doxil can be considered as part of a combination therapy (26). We have combined both objectives evaluating the potential of PC3-specific phage fusion protein as a liposomal navigating ligand using Doxil as a model therapeutic liposome and evaluating if targeting results in higher doxorubicin cytotoxicity in vitro.

The targeting studies using Rhodamine-labeled liposomes demonstrated that targeted liposomes associate with target cells preferentially in a mixture of cells and this can be used as a measure of their selectivity toward PC3 cells. This assay models an in vivo scenario in which liposomes must distinguish between normal and neoplastic cells based on molecular differences identified by the targeting peptide. Flow cytometry assessment testing the association of liposomes modifed with an unrelated phage peptide showed only low levels of non-specific association of liposomes with the target cells. These associations may arise due to the natural propensity of liposomes to associate with lipid membranes or due to non-specific binding abilities conferred onto liposomes due to modification with phage coat proteins.

In western blot experiments, treatment with proteinase K gave different results with different preparations implying that the membrane insertion process probably depends on the guest peptide composition as well as its interactions with its surrounding amino acids of the phage coat protein. This observation is supported by studies elucidating the thermodynamic interactions involved in the process of membrane insertion of phage coat proteins (14, 27, 28). We have previously demonstrated that a guest peptide interacts with the amino acids in its immediate surroundings (29). Such interactions may in turn affect the insertion process and so the insertion efficiency and orientation of the coat protein unit may differ from peptide to peptide.

The results of the cytotoxicity assays demonstrated that target-specific liposomes possessed a higher toxicity in PC3 cell cultures than the control liposomes. The relatively higher cytotoxicity of liposomes modified with an unrelated phage fusion protein, 7b1, compared with the results of the targeting assays in which labeled liposomes modified with the same peptide showed higher levels of binding with target cells than other control liposomes. This observation may be due to non-specific association of these control liposomes with the cells and demsonstrates the need for optimizing this strategy for the production of targeted liposomes. Our results thus provide support for further research directed towards the application of targeted liposomes in clinically significant tumor conditions like HRPC.

Targeting of drug carriers has been shown to have measurable therapeutic benefits. A limiting factor in the development of targeted liposomal therapeutics has been the chemical conjugation reactions required to append targeting ligands to liposomes. Our approach exploiting the physico-chemical properties of bacteriophage coat proteins circumvents any chemical modification techniques as targeted preparations are obtained by directly incubating liposomes and the target-specific phage fusion protein. An additional advantage is the rapid identification of target-specific phage probes using high throughput screening with phage display libraries. Thus, novel targeted liposomal preparations can be rapidly obtained in a combinatorial manner which should provide a more streamlined approach for the development of new targeted treatments of malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Representative data for size distribution of phage fusion protein-modified labeled liposomes (A) and non-modified labeled liposomes (B). The grafting of phage fusion protein onto liposomes did not alter the physical characteristics of the liposomes.

Transmission electron microscopy of liposomal formulations. (A) Plain liposomes without phage coat protein (B) Phage coat protein modified liposomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NIH-1 R01 CA125063-01 (to V.A.P.). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute of NIH.

Footnotes

There are no disclosures or any conflicts of interest with regard to this publication.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gerber DE. Targeted therapies: a new generation of cancer treatments. American family physician. 2008;77:311–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths GL, Mattes MJ, Stein R, Govindan SV, Horak ID, Hansen HJ, et al. Cure of SCID mice bearing human B-lymphoma xenografts by an anti-CD74 antibody-anthracycline drug conjugate. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9:6567–6571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundberg BB. Cellular Association and Cytotoxicity of Doxorubicin-Loaded Immunoliposomes Targeted via Fab′Fragments of an Anti-CD74 Antibody. Drug Delivery. 2007;14:171–175. doi: 10.1080/10717540601036831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein R, Qu Z, Cardillo TM, Chen S, Rosario A, Horak ID, et al. Antiproliferative activity of a humanized anti-CD74 monoclonal antibody, hLL1, on B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2004;104:3705–3711. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arap W, Haedicke W, Bernasconi M, Kain R, Rajotte D, Krajewski S, et al. Targeting the prostate for destruction through a vascular address. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:1527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241655998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellerby HM, Arap W, Ellerby LM, Kain R, Andrusiak R, Rio GD, et al. Anti-cancer activity of targeted pro-apoptotic peptides. Nat Med. 1999;5:1032–1038. doi: 10.1038/12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE, Fujimora S, John V. Hunter-Killer Peptide (HKP) for Targeted Therapy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51:5887–5892. doi: 10.1021/jm800495u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerlag DM, Borges E, Tak PP, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE, Pasqualini R, et al. Suppression of murine collagen-induced arthritis by targeted apoptosis of synovial neovasculature. Arthritis Research. 2001;3:357–361. doi: 10.1186/ar327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolonin MG, Saha PK, Chan L, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:625–632. doi: 10.1038/nm1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. Journal of Controlled Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torchilin VP, Levchenko TS, Lukyanov AN, Khaw BA, Klibanov AL, Rammohan R, et al. p-Nitrophenylcarbonyl-PEG-PE-liposomes: fast and simple attachment of specific ligands, including monoclonal antibodies, to distal ends of PEG chains via p-nitrophenylcarbonyl groups. BBA-Biomembranes. 2001;1511:397–411. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishida T, Iden DL, Allen TM. A combinatorial approach to producing sterically stabilized (Stealth) immunoliposomal drugs. FEBS Letters. 1999;460:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iden DL, Allen TM. In vitro and in vivo comparison of immunoliposomes made by conventional coupling techniques with those made by a new post-insertion approach. BBA-Biomembranes. 2001;1513:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiefer D, Kuhn A. Hydrophobic forces drive spontaneous membrane insertion of the bacteriophage Pf3 coat protein without topological control. Embo J. 1999;18:6299–306. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprujit RB, Wolfs CJAM, Hemminga M. Aggregation-Related Conformational Change of the Membrane-Associated Coat Protein of Bacteriophage M13. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9158–9165. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayanna PK, Torchilin VP, Petrenko VA. Liposomes targeted by fusion phage proteins. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2009;5:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayanna PK, Deinnocentes P, Bird RC, Petrenko VA. NSTI Nanotech. Boston: 2008. Landscape phage probes for PC3 prostate carcinoma cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brigati JR, Samoylova TI, Jayanna PK, Petrenko VA. Phage display for generating peptide reagents. In: Coligan DBMJE, Speicher DW, Wingfield PT, editors. Current Protocols in Protein Science. Unit 18.9. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008. pp. 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.2009, posting date. American Cancer Society. [Online.]

- 20.Chowdhury S, Burbridge S, Harper PG. Chemotherapy for the treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2007;61:2064–2070. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomerantz M, Kantoff P. Advances in the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Annual Review of Medicine. 2007;58:205–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.101505.115650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee R, Tyagi P, Li S, Huang L. Anisamide-targeted stealth liposomes: A potent carrier for targeting doxorubicin to human prostate cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;112:693–700. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elbayoumi TA, Pabba S, Roby A, Torchilin VP. Antinucleosome antibody-modified liposomes and lipid-core micelles for tumor-targeted delivery of therapeutic and diagnostic agents. Journal of Liposome Research. 2007;17:1–14. doi: 10.1080/08982100601186474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elbayoumi TA, Torchilin VP. Enhanced cytotoxicity of monoclonal anticancer antibody 2C5-modified doxorubicin-loaded PEGylated liposomes against various tumor cell lines. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;32:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2007.05.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ElBayoumi TA, Torchilin VP. Tumor-Targeted Nanomedicines: Enhanced Antitumor Efficacy In vivo of Doxorubicin-Loaded, Long-Circulating Liposomes Modified with Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15:1973–1980. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Zawahry A, McKillop J, Voelkel-Johnson C. Doxorubicin increases the effectiveness of Apo 2 L/TRAIL for tumor growth inhibition of prostate cancer xenografts. BMC cancer. 2005;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soekarjo M, Eisenhawer M, Kuhn A, Vogel H. Thermodynamics of the Membrane Insertion Process of the M13 Procoat Protein, a Lipid Bilayer Traversing Protein Containing a Leader Sequence. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1232–1241. doi: 10.1021/bi951087h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiaudiere E, Soekarjo M, Kuchinka E, Kuhn A, Vogel H. Structural characterization of membrane insertion of M13 procoat, M13 coat, and Pf3 coat proteins. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12186–96. doi: 10.1021/bi00096a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuzmicheva GA, Jayanna PK, Sorokulova IB, Petrenko VA. Diversity and censoring of landscape phage libraries. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection. 2009;22:9–18. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzn060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Representative data for size distribution of phage fusion protein-modified labeled liposomes (A) and non-modified labeled liposomes (B). The grafting of phage fusion protein onto liposomes did not alter the physical characteristics of the liposomes.

Transmission electron microscopy of liposomal formulations. (A) Plain liposomes without phage coat protein (B) Phage coat protein modified liposomes.