Abstract

This manuscript reports the results of a study that pilot tested a home-delivered, multi-dimensional problem-solving intervention aimed at helping aging parental caregivers of adult children with schizophrenia. The results indicate that the participants (N=5) who received the 10-session intervention showed increased life satisfaction and emotional well being, and reduced feelings of burden, compared to those participants in the control group (N=10). If a planned larger scale evaluation of the intervention provides evidence of its effectiveness, practitioners could have a valuable new treatment tool to provide assistance to this caregiver population.

Keywords: Aging Parental Caregivers, Adults with Schizophrenia, Multi-Dimensional Intervention

Introduction

Aging parents of adults with serious mental illness (SMI) are often called upon to provide long-term or even life-long assistance to their disabled children, because of the chronic and episodic nature of SMI. This comes at a stage in life when most other aging parents can look forward to their adult children achieving self-sufficiency and independence. These issues are often further complicated by shortages of formal services and residential options for persons with SMI (Biegel, Song, & Chakravarthy, 1994; Lefley, 2009; Solomon, 2000). The complex and debilitating problems experienced by these adult children, and their continued dependency, may have serious negative consequences for their aging parents. The on-going assistance that these aging parents are frequently called upon to provide comes at a time when they are often struggling to deal with issues and challenges related to their own aging. This may ultimately threaten their ability to meet the long-term supportive needs of their SMI adult children (Kelly & Kropf, 1995; Jennings, 1987). Despite an increasing number of intervention studies that have targeted families of adults with SMI, there has been little research that has focused exclusively on developing interventions to address the unique needs of aging parental caregivers of this population.

The purpose of this study was to pilot test a home-delivered, multi-dimensional problem-solving intervention aimed at improving the emotional well-being and the life satisfaction of aging parental caregivers of adult children with schizophrenia. It was the researchers’ intention to test the feasibility of the planned methodology, and to use the pilot data obtained from this exploratory study, for the development of a larger scale test of the effectiveness of the planned intervention.

It was predicted that at post intervention assessment, the aging parental caregivers in the treatment group would show improved emotional well-being and life satisfaction compared to the participants in the control group. Because this pilot study, by design, was limited to a small sample of participants, it lacked the power needed for a conventional statistical test of this hypothesis.

Family Caregiving for Adults with SMI

Of the approximately 3 to 5 million SMI adults in this country, it is estimated that between 35% and 75% live with family members (Bengtsson-Topps & Hansson, L, 2001; Lefley, 1996; National Institute of Mental Health, 1991; Solomon, 2000). Most often these family caregivers are older parents who are in their 50s or 60s (Lefley, 1987; World Federation for Mental Health., 2007). Many other persons with SMI, who live separate from their families, are nonetheless quite dependent upon family members for considerable amounts of social support and assistance with a variety of needs (Laidlaw, Coverdale, Falloon, & Kydd, 2002; Tessler & Gamache, 2000). The increasing life expectancies of persons with SMI combined with reductions in institutional care for such individuals and a concomitant growth of community-based residential options has placed greater demands on their families to provide care (Greenberg & Greenley, 1997; National Institute of Mental Health, 1991; World Federation for Mental Health, 2007). For persons with SMI who require hospital based care, these stays are shorter than in the past, with the result that many of these persons return to their communities and to their families in a more severe condition than was previously the case (Barrowclough, 2005; Biegel, 1998; Lefley, 2009).

The family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia are most often parents, who can expect their son or daughter to outlive them. In this respect, they are unlike the family caregivers of physically or cognitively impaired aged persons who are generally the spouses or adult children of those individuals. Consequently, a commonly experienced concern for these parents focuses on the future care needs of their children when the parents will no longer be able to provide help to them (Greenberg & Seltzer, 2001; Kaufman, 1998; Lefley, 2009; Lefley & Hatfield, 1999; Mengel, Marcus, & Dunkle, 1996; Pickett & Greenley, 1995).

It is well established that family members find it stressful to deal with the symptomatic behaviors of persons with SMI (Winefield & Harvey, 1993; Tessler & Gamache, 2000). Long-term caregiving to mentally ill family members has been associated with feelings of worry, guilt, resentment, and grief (Lefley, 1996). The following have been identified as major problems experienced by these caregivers: coping with problem behaviors; dealing with feelings of isolation; interference with household routines and with meeting the personal needs of other family members; not having adequate information about the SMI person’s illness; dealing with problems in medication management and compliance; coping with problems related to the SMI relative’s impaired social role performance and ability to carry out tasks required for daily living; disruptions to family life; lack of a respite from caregiving responsibilities; and insufficient help from the mental health service system (Baronet, 1999; Biegel & Schulz, 1999; Lefley, 2009). Solomon (2000) has identified the needs of these caregivers as falling into these categories: information about the nature, intervention, and management of the SMI relative’s illness; skills to cope with problems related to the illness (including its effects on the family); and recognition and social support of their caregiving efforts.

Parental caregivers of children with SMI may be negatively impacted by a variety of contextual issues such as the stresses many experience in interfacing with the public systems (mental health, medical, housing, and social services) charged with providing services to their loved ones. Families are commonly faced with having to make up for the gaps and inadequacies in these systems because in many communities such services are available only in a limited fashion (Lefley, 1996; Pepper & Ryglewicz, 1984; Solomon, 2000). While family members caring for mentally ill relatives do note some rewards associated with these relationships (Bulger, Wandersman, & Goldman, 1993; Chen & Greenberg, 2004; Greenberg, 1995; Greenberg, Greenley, & Benedict, 1994; Schwartz & Gidron, 2002), caring for mentally ill family members is generally thought to have a negative impact on the family and is perceived as a family burden, with the course of such caregiving burdens often being unpredictable and lasting for many years (Biegel & Schulz, 1999; Lefley, 1996). The degree of experienced caregiver burden has been associated with care recipient characteristics such as age, sex, duration of illness, functional status, symptomatology, and number of previous psychiatric hospital admissions (Cook, Lefley, Pickett, & Cohler, 1994; Jones, Roth, & Jones, 1995; Solomon & Draine, 1995). Caregiver characteristics found to be associated with varying degrees of burden include sex, age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, health status, kin relationships, and living situation (Cook et al., 1994; Jones et al., 1995; Solomon & Draine, 1995; Winefield & Harvey, 1993). Social support, coping skills, and self efficacy have been found to act as mediating factors (Birchwood & Cochrane, 1990; Solomon & Draine, 1995).

Families who lack knowledge about schizophrenia may attribute a mentally ill person’s problematic symptoms to behavioral factors such as laziness rather than to an illness (Kavanagh, 1992; Lefley, 2009). Lack of knowledge about the disorder may also contribute to feelings of subjective burden. Some researchers have suggested that subjective burden is a stronger predictor of caregiver distress than the caregiver’s level of objective burden, or the patient’s symptomatology (Cousins, Davies, Turnbull, & Playfer, 2002; Noh & Avisan, 1988). Role captivity and responsibility for multiple caregiving roles, family conflict about caregiving, and criticism or lack of acknowledgement by other family members, are variables found to be positively related to feelings of subjective burden (Schulz, O’Brien, Bookwala, & Fleissner, 1995).

Interventions for Family Caregivers of Adults with SMI

Interventions that target families of persons with SMI typically fall into one of the following categories: (1)psycho education, (2) family education, (3) family support groups, (4) individual family support (also called family consultation), and (5) multi-component interventions (Biegel, Robinson, & Kennedy, 2000; Fallon, I. R. H., 2005). Psycho educational interventions provide family members with information about mental illness, and teach family members strategies and skills to help them more effectively cope with the challenges they encounter (Hatfield, 1997; Penn & Mueser, 1996; Solomon, 1996, 2000). Researchers have found psycho educational interventions to be associated with reductions in feelings of anxiety, depression, burden and stress, along with improvements in coping abilities, family relations and family functioning (Abramowitz & Coursey, 1989; Biegel et al., 2000; Biegel & Schulz, 1999; Corcoran & Phillips, 2000; Dixon & Lehman, 1995; Falloon, Boyd, & McGill, 1984; Lukens, Thorning, & Herman, 1999).

Family education programs developed as grassroots responses to the lack of information and services provided to the families of SMI persons by mental health service providers (Hatfield, 1990; Solomon, 1996). These programs, usually conducted as group interventions, provide social support as well as information to participants. Most family education programs attempt to help participants deal better with stress and crisis (Solomon, 2000). Outcome studies have found these interventions to be associated with reduced feelings of burden, distress, and anxiety for family members, along with improvements in their coping abilities, increased self-efficacy, and reductions in levels of family conflict (Biegel et al., 2000; Budd & Hughes, 1997; Goldberg-Arnold, Fristad, & Gavazzi, 1999; Hugen, 1993; Solomon, 1996).

Family support groups provide a forum where families can receive information about mental illness and engage in advocacy activities in an emotionally supportive atmosphere that provides opportunities to share experiences and feelings without fear of stigma. The main focus of these programs is on the provision of mutual support offered by families who share similar circumstances (Lefley, 1996; Solomon, 2000). Rigorous research on the efficacy of family support groups is lacking (Solomon, 2000). The limited research that has been conducted suggests that participation in family support groups is related to improved coping skills, increased access to information, perceptions of increased social support and reduction in feelings of subjective burden and psychological distress (Biegel et al., 2000; Citron, Solomon, & Draine, 1999; Heller et al., 1997; Norton, Wandersman, & Goldman, 1993).

In individual family support programs (family consultation), consultants, usually under the auspices of a mental health center, provide family members with supportive advice and information regarding specific problems they are experiencing in their relationship with an SMI family member. These interventions are intended to be short-term in nature and focus on only one or two issues of concern (Citron et al., 1999; Solomon, Draine & Mannion, 1996; Solomon, 2000). Research focusing solely on the efficacy of individual family support interventions is lacking. However, Solomon and her colleagues, in evaluating individual family support as one component of a more comprehensive randomized study, found such consultation associated with an increase in self-efficacy on the part of family members regarding their ability to cope with an SMI family member’s behavior (Solomon et al., 1996; Solomon et al., 1997).

In their review of family intervention studies, Biegel et al. (2000) discuss two state-wide studies of family support programs that used multi-component intervention approaches. The first was a study of 12 programs in Massachusetts that offered participants from two to ten different types of family support services. A second study in New Jersey included eight programs, with six different services ranging from support groups, to respite care and advocacy. While these studies found evidence of decreased burden, the authors state that the data presented are difficult to interpret because of the diversity of the interventions used.

Theoretical Model

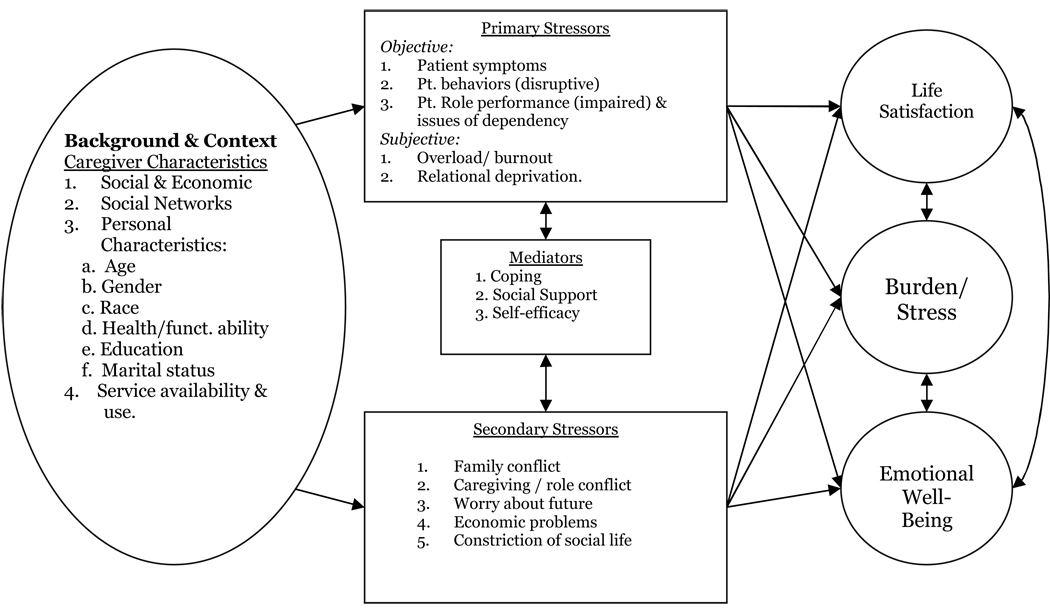

The theoretical model that guided the development of this study is shown in Figure 1. This model was adapted from two sources. The first source is the well-known caregiving and stress process model by Pearlin, et al. (1990) that identifies stressors and role strains, often encountered by caregivers, that may lead to negative outcomes such as anxiety, depression, cognitive disturbances, and problems with physical health. While originally developed to identify the stress process experienced by caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease, this model has increasingly been used by researchers to examine the stress process effecting other caregiver populations. The second source is a model by Platt, Weyman, Hirsch, and Hewett (1980) that identifies a range of problematic behaviors and impaired functional abilities, often displayed by persons with SMI that have been linked to negative outcomes for their family members and friends.

Figure 1.

Consequences of Caring for a Seriously Mentally Ill Relative

The study’s model, titled “Consequences of Caring for A Seriously Mentally Ill Relative,” identifies a set of primary and secondary stressors, influenced in part by a group of individual caregiver and background contextual variables that are seen as affecting the caregiver’s life satisfaction, emotional well-being, and levels of experienced burden and stress. The primary stressors noted in the model include patient symptoms, disruptive patient behaviors, impaired patient role performance and issues of dependency, caregiver role overload/burnout, and caregiver relational deprivation. Secondary stressors include family conflict, caregiving/role conflict, caregiver concerns about the future, constriction of caregiver social activities, and economic problems. The model identifies coping, social support, and self-efficacy as having potential mediating effects directly upon the primary and secondary stressors, and on the interfaces or interactions between those stressors. It is necessary to note that while this model helped to guide this modest pilot study, the study was not designed to test the model.

Methods

Participants

It was decided to limit participation in the study to aging parental caregivers of adult children with schizophrenia because persons with this diagnosis comprise one of the largest and most severely impaired subgroups of individuals with SMI (Barrowclough, 2005; Greenberg & Greenley, 1997; Hatfield, 2000; Reinhard & Horwitz, 1995; Seltzer, Greenberg, Krauss, Gordan, & Judge, 1997; Solomon, Draine, Mannion, & Meisel, 1997; World Federation for Mental Health, 2007). It was thought that this approach would provide a large population from which to recruit study participants, while avoiding the potential confounds associated with differences in the caregiving experiences of aging parents of adult children who carry other SMI diagnoses.

It was the researchers’ intention to recruit equal numbers of African American and White parental caregivers to examine possible differential effects of the intervention and to test the soundness of the recruitment strategy for generating sufficient numbers of African American participants for a larger scale planned future study. Participants were recruited from a four county area in west central Alabama, with the assistance of area community mental health centers, area chapters of the National Alliance of the Mentally Ill, the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and through a publicity campaign designed to encourage self referrals and referrals from community organizations. Every aspect of the research methodology utilized in this study was approved by the University of Alabama’s Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects (IRB), and by the IRB of the Tuscaloosa Veterans Administration Medical Center.

To be eligible for this study, participants had to: be 60 years of age or older; have an adult child over the age of 21 who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia by a recognized mental health provider; have provided that child with an average of 6 hours of care (described below) per week during the past month; have had an absence of significant cognitive impairment as indicated by a score of 24 or higher (17 or higher for those with only an eighth grade education) on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975); have not been previously or were not currently in receipt of any type of individual or group intervention for caregivers; and have had no self-reported history of schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, major depressive disorder, or self-reported current substance abuse. Additionally, eligible participants had to have met two of the following three criteria: a decrement in life satisfaction as evidenced by a T-score below 50 on the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) (Frisch, 1992); the presence of significant emotional distress as evidenced by a T-score of greater than 50 on the Global Severity Index (GSI) of the SCL-90-R (Derogatis, Rickels, & Rock, 1976); a moderate degree of caregiver burden as evidenced by a score of 41 or higher on the Zarit Burden Instrument (Zarit & Zarit, 1983; Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985).

A further requirement for eligibility concerned the type of care that potential participants were required to have provided to their adult child with SMI during the month prior to entrance into the study. At least 3 of the required 6 hours of care had to have been in the form of direct contact; providing assistance with instrumental activities of daily living, emotional support and companionship, or assistance carrying out prescribed social role activities. Subsequent hours of care could have been care provided indirectly, as in the provision of emotional support delivered through telephone contact.

In those family situations where two parents met the eligibility criteria and both wished to participate, only one parent was allowed into the study. In such situations, it was decided to invite in that parent acknowledged by both parents as the primary caregiver. However, if there was no consensus about this issue, and if both parents wished to participate, the dyad was asked to select one parent to participate in the study.

Sample

In view of the purpose of this pilot study, discussed above, a conventional power analysis to determine an appropriate sample size for this study was not used. Using such an approach would have resulted in requiring a sample size too large for this study’s time and budgetary constraints. Therefore, a more subjective approach was used to determine an adequate sample size that would provide a sufficient number of participants to: 1) identify potential treatment effects; 2) test the feasibility of the proposed plan for delivering the intervention in the number of sessions planned; 3) test the suitability and applicability of the treatment manual and other treatment materials developed for this study; 4) determine the feasibility and appropriateness of our recruitment strategies, and the utility of those strategies for obtaining a larger size sample for a future expanded test of the intervention. Based on these considerations, it was decided that a final sample (after allowing for attrition) of 40 participants (20 in the intervention group and 20 in the control group) would provide an adequate number of participants to achieve these goals.

To minimize attrition, all participants (intervention group and control group) received an incentive payment of a $25 gift certificate for each psychosocial assessment that they completed. Additionally, all control condition participants received brief bi-weekly telephone calls from project staff to sustain their interest in participation during the control period. In order to achieve uniformity with these telephone calls, project staff making the calls followed an IRB approved script.

Unfortunately, despite a recruitment plan that sought to obtain a final sample of 40 participants, only 18 parental caregivers entered the study, with only 15 participants (treatment condition N=5; control condition N=10) actually completing the research protocol. The problems encountered in recruiting participants for this study are discussed below.

Design

A wait-list control (delayed treatment) experimental design (Kazdin, 2003) was used to examine the impact of the brief problem-solving intervention on the life satisfaction and emotional well-being of the aging parental caregivers in the study. Participants in the immediate intervention group (N=5) were assessed twice: pre-intervention and one month post-intervention. Participants in the delayed treatment control group (N=10) were assessed three times: at entry into the study, at the end of the fourteen week waiting period (pre-intervention), and one month following completion of the ten session intervention (post-intervention). Post-treatment assessments for both groups were conducted one month following the end of treatment rather than immediately after treatment to reduce the possibility of obtaining inflated positive treatment outcomes.

Intervention Procedure

After completing Assessment 1, all eligible participants were randomly assigned to either the immediate treatment group or the control group. Participants in the immediate treatment group began their 10-session intervention program as soon as possible after Assessment 1. Assessment 2 was administered to these participants one month following their final treatment session. Participants in the control condition received Assessment 2 fourteen weeks following Assessment 1 and received Assessment 3 one month following their last intervention session. All assessments were administered by an MSW level social worker hired and trained for this study.

Intervention Program and Rationale

The intervention consisted of 10 ninety-minute sessions, delivered weekly in the caregivers’ homes by master’s level social workers. Figure 2 provides a graphic illustration of the components of the intervention framework. The major integrating component of the intervention package was a problem-solving approach adapted from the work of D’Zurilla and Goldfried (1971), D’Zurilla and Nezu (1982, 1999), Epstein (1992), and Naleppa and Reid (2003). Problem-solving as an intervention technique has extensive empirical support (D’Zurilla, 1986; D’Zurilla & Nezu, 1982) and has been found to be effective in work with family caregivers (Burgio, Stevens, Guy, Roth, & Haley, 2003; Gendron, Poitras, Dastoor, & Perodeau, 1996; Toseland, Blanchard, & McCallion, 1995).

Figure 2.

Intervention Framework

The problem-solving component in this study used a 5-step approach: 1) identify the problem(s); 2) prioritize the problems and establish problem-solving goals; 3) generate potential approaches to work on the problem(s) and decide upon a plan of action; 4) implement the action plan; 5) evaluate the outcome of the implemented plan and establish a plan for the future if the problem(s) persists or returns. Problem-solving training and practice spanned the entirety of the intervention program. Session 1 and part of session 2 focused specifically on teaching the problem-solving process, and applications of the technique occurred in subsequent sessions.

Providing psycho education about schizophrenia to the participants comprised the second component of the intervention program. Sessions 2 and 3 were devoted to this topic. Support for providing psycho education to caregivers comes from studies such as Solomon et al. (1996). These investigators found that a psycho education program increased the self-efficacy of family members who cared for relatives with serious mental disorders. Biegel et al. (2000), in their review of empirical studies of interventions for families of persons with mental disorders, found support for the efficacy of such programs, although they note a number of methodological difficulties with the existing literature. Budd and Hughes (1997) support the inclusion of psycho education in a multi-component intervention through their finding that family members most commonly cited increased knowledge of schizophrenia as the most helpful aspect of a family program.

Sessions 4 and 5 focused on helping the caregivers acquire knowledge and techniques to assist them in the management of their disabled child’s problematic behaviors. There is ample research evidence that suggests that behaviors associated with the symptoms of SMI such as substance abuse, extreme dependency, hostility, apathy, and difficulty with interpersonal relationships, along with problem behaviors related to such issues as medication compliance and impaired social role performance, are major sources of distress for family members of persons with SMI (Cook & Pickett, 1987; Reinhard & Horwitz, 1995; World Federation for Mental Health., 2007; Zauszniewski, Bekhet, & Suresky, 2009). The management of a variety of behavior-related crises involving persons with SMI has also been identified as a source of distress and burden for their family members (Lefley, 1996). Therefore, these sessions were devoted to helping parents identify early symptoms of potential crises and emergency situations involving their disabled children, and how to adapt the problem-solving model to deal with these problems.

Sessions 6, 7, and 8, were devoted to stress management and the mastery of cognitive restructuring skills; more specifically skills in the identification and modification of maladaptive information processing styles. The efficacy of cognitive therapy techniques across a variety of disorders and populations has been well-established (Chambless & Ollendick, 2000). Cognitive therapy techniques such as the three and five column techniques have been used in family caregiving interventions to reduce depression, stress and burden (Gallagher-Thompson, & Steffen, 1994; Gallagher-Thompson, Coon, Solano, Ambler, Rabinowitz, & Thompson, 2003).

A major stressor for aging parental caregivers of persons with serious mental disorders is concern about meeting the future needs of their emotionally disabled adult children (Cook et al., 1994; Hatfield & Lefley, 2005; Jennings, 1987; Lefley, 1987; Mengel et al., 1996). Therefore, future planning was the final component of the intervention protocol, and was the focus of sessions 9 and 10. Topics that have been identified as important to this domain; future planning for the care of the impaired adult child, resource allocation in the event of parental diminished capacity, and the assumption of responsibility for care by other family members or social agencies (Kaufman, Adams, & Campbell, 1991; Kaufman, 1998), were covered in these sessions.

Measures

The following measures were used in this study:

Caregiver Cognitive Competence

The cognitive competence of potential caregiver study participants was assessed through the use of the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975), a widely used instrument to assess cognitive deficits in adults. This instrument was administered during the first assessment interview. Only potential participants whose scores showed an absence of significant cognitive impairment as indicated by a score of 24 or higher (17 or higher for those with only an eighth grade education) were considered eligible for continued participation in the study.

Sociodemographic Information

Information was obtained on age, sex, race, marital status, educational attainment, income, and employment status.

Caregiver Burden

Caregiver burden was measured using the 22-item version of the Zarit Burden Interview (Zarit & Zarit, 1983; Zarit, Orr, & Zarit, 1985). This instrument is perhaps the most widely used measure of caregiver burden, and has been found to be both a reliable and valid measure.

Caregiving Assistance

An adapted version of the assistance in daily living module of the Family Burden Interview Schedule – Short Form (Tessler & Gamache, 1994) was used to measure the types and amount of assistance participants provided to their adult SMI children during the previous month. This 8-item scale asks respondents to provide information about their provision of assistance with the following daily living activities: dressing and personal hygiene, housework, meal preparation, shopping, transportation, financial management, medication management, and time management.

Life Satisfaction

The 16 item Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) (Frisch, 1992) was used to measure the construct “life satisfaction.” This instrument, based on a model presented by Frisch (1998), is a measure of an individual’s subjective feeling of well-being as it is influenced by a variety of objective factors. According to this model, the objective factors that influence an individual’s life satisfaction are mediated by the importance or value attached to them by the individual. The test-retest reliability of the QOLI was .73 and coefficient alpha was .79. Participants were selected based on a QOLI T-score below 50. This cut-score was chosen to identify those individuals who reported below average feelings of subjective well-being, and to ensure that there was sufficient room for improvement.

Emotional Well-Being

The SCL-90-R was chosen to measure participants’ overall level of emotional well-being. The 90 items of the SCL comprise nine subscales: anxiety, depression, psychoticism, paranoid ideation, phobic anxiety, somatization, obsessive compulsive, hostility and interpersonal sensitivity. The psychometric properties of the SCL-90-R are well established (Derogatis et al., 1976) and it has been endorsed as a core instrument for clinical intervention studies. This study used scores from the Global Severity Index (GSI). This is an indicant of overall emotional distress. One aspect of the study’s inclusion criteria was that parental caregiver participants score above a 50 T-score on this scale in order to be able to observe change on this outcome variable.

Data Analysis and Findings

The analysis conducted derived from the pre/post treatment/control design of the study methodology discussed above in which participants were randomly assigned to an intervention (treatment) group or a control (delayed intervention) group. Baseline (pre) measurements were obtained as well as post-intervention measurements for the treatment group and post-test measurements from the control group for the same time interval. The two outcome measures noted in the research hypotheses were analyzed: caregiver life satisfaction (QOLI T-Score), and caregiver emotional well-being (SCL-90 GSI T-Score). Additionally, the intervention's effect on the participants' feelings of caregiver burden was also analyzed (Zarit Burden Interview - Total Score). The analysis technique used was repeated measures analysis of variance with the pre/post comparison being the within subjects variable and the treatment/control group comparison being the between subjects variable. The statistical significance of interaction effects was assessed separately for each outcome measure. In a complete data subset of participants, five (5) treated participants were compared to 10 control group participants. Three participants in the treatment group did not complete the treatment protocol with the consequence that no post-test data for these individuals was available.

The treatment group (N=5) contained three mothers and two fathers with a mean age of 67, while the control group (N=10) which had a mean age of 68, was composed of only mothers. All of the parents in the treatment group were White, compared to the control group which contained three African American parents and seven White parents. Among the parents in the treatment group, one parent was a high school graduate, one had some college, and three parents reported that they were college graduates. For the control group, five had completed high school, four had some college, and one parent was a college graduate. Among the members of the treatment group, three were currently married, while the other two were divorced, separated, or never married. For the control group, four parents were currently married while the remaining six reported that they were divorced, separated, or never married. At the time of the study, one parent in the treatment group was employed full time, while the other four reported that they were retired. For the control group, four parents were employed, while the remaining six, reported they were either retired, or otherwise unemployed.

The findings for the repeated measures analysis of variance for the outcome variables life satisfaction, emotional well-being, and caregiver burden are displayed in Table 1. The participants' life satisfaction mean scores (QOLI) increased from 30.8 (s.d. = 13.1) to 52.0 (s.d. = 13.7) for the treatment group. QOLI mean scores increased slightly from 43.8 (s.d. = 8.8) to 45.0 (s.d. = 8.8) for the control group. Interaction was statistically significant (p = .03). This finding supported the research hypothesis that the participants in the treatment group would show increased life satisfaction compared to the participants in the control group.

Table 1.

Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance

| Experimental Group (N = 5) vs. Control Group (N = 10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline: Mean (s.d.) | Time 2: Mean (s.d.) | p-value* | |

| QOLI (T-Score) | |||

| Experimental | 30.8 (13.1) | 52.0 (13.7) | .03 |

| Control | 43.8 (8.8) | 45.0 (8.8) | |

| SCL-90 GSI (T-Score) | |||

| Experimental | 62.8 (9.0) | 55.6 (1.8) | .01 |

| Control | 58.7 (4.6) | 60.8 (3.6) | |

| Zarit (Total Score) | |||

| Experimental | 43.6 (12.4) | 28.0 (9.7) | .02 |

| Control | 46.1 (12.7) | 42.7 (13.0) | |

p-values are for interactions (group × time)

Mean scores for the outcome variable emotional well-being (SCL-90 GSI) decreased from 62.8 (s.d. = 9.0) to 55.6 (s.d. = 1.8) for the treatment group. SCL-90 mean scores increased from 58.7 (s.d. = 4.6) to 60.8 (s.d. = 3.6) for the control group. Interaction was statistically significant (p = .01). This finding supported the research hypothesis that the tested intervention would have a positive effect on the emotional well-being of the participants in the treatment group compared to those in the control group.

Caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview) mean scores decreased from 43.6 (s.d. = 12.4) to 28.0 (s.d. = 9.7) for the treatment group. Caregiver burden mean scores decreased from 46.1 (s.d. = 12.7) to 42.7 (s.d. = 13.0) for the control group. Interaction was statistically significant (p = .02). The participants who received the intervention showed a significant reduction in feelings of caregiver burden compared to those participants in the control group.

Discussion

As noted above, until now, interventions that have attempted to help family caregivers of persons with serious mental illness have focused almost exclusively upon the provision of psycho education, family education, group support, or individual supportive services. The intervention that was pilot tested in this study goes beyond those traditional approaches to help aging parental caregivers of adult children with schizophrenia acquire additional information and skills that is thought will benefit them and assist them to continue in their caregiving roles. The results of the data analyses presented above indicate that for the aging parents in this pilot study the 10-session multi-dimensional intervention that was tested appears to have had a positive effect on the emotional well-being, life satisfaction, and feelings of caregiver burden for those in the treatment group compared to the participants in the control group. Because of the small number of participants these findings while they are very promising are quite tentative. These pilot data should provide ample support for a further test of the intervention with a larger, more diverse group of older parental caregivers.

It was disappointing not being able to recruit a larger and more diverse group of participants for this pilot study. The original proposal stated a recruitment goal of a final sample of 20 participants per condition, with half of the participants being African American and half White. The research team’s inability to recruit the number and diversity of participants proposed was due to several factors. Funding cuts imposed on this project in both project years limited the resources available for recruitment activities. In addition, several of the agencies that had initially shown great enthusiasm for the study, and that had provided assurances of help in recruiting participants, did not meet expectations for their promised assistance. Problems similar to the ones encountered in this study, in recruiting a sample of family members of adults with serious mental illness through the assistance of community treatment facilities, have been reported by other researchers (Drapalski, et al., 2008).

This research team’s ability to overcome such problems is critically important for the potential success of future research efforts. The team’s experience with this pilot study has helped it to identify several strategies that should improve the success of future recruitment efforts. Aging parental caregivers of adult children with serious mental illness constitute a rather hidden and often stigmatized population. To find these persons and to successfully recruit them to participate in clinical research studies, it is necessary to employ recruitment specialists as part of the research team. As members of the research team, such specialists would focus all their efforts on working with cooperating agencies and community organizations in identifying and recruiting study participants. These team members would also be able to develop community outreach efforts to identify gatekeepers that might help in the recruitment process. Additionally, having staff dedicated solely to participant recruitment would facilitate the development of a community publicity campaign using various media sources to encourage self referral of potential research participants.

Another approach to increase potential participant recruitment would be to establish a multisite research effort, through cooperative arrangements with researchers at other institutions in other areas of the country. In addition to increasing the potential to recruit aging parental caregivers for an efficacy test of this intervention, establishing a multisite research approach would provide an opportunity test the external validity of the intervention. When testing the efficacy of an intervention that is limited in scope to one research setting, there are always questions about whether the results that are obtained can be generalized to other settings and to participants in those other settings. Obviously, because multisite studies tend to be more costly than single site studies, such an approach would depend upon the availability of funding, and the ability of the researchers involved in obtaining the needed resources.

Conclusion

In our current economic climate, most community based human service agencies are faced with a continuous struggle to obtain the resources needed to provide an adequate level of formal care and services to persons with serious and chronic mental health problems. As the service and therapeutic needs of this population continue into the future, the importance of family members as the providers of assistance to persons with SMI will increase due, in part, to the increasing budgetary pressures most human service agencies are likely to experience.

As noted above, most often, these family care providers are the parents of these persons with SMI who, as they and their mentally ill child grow older, encounter an increasing number of challenges in their ability to continue their caregiving role. It is imperative that social work practitioners who work with these family units be knowledgeable about the issues and challenges faced by these older parents in order to assist them to continue providing the assistance needed by their disabled children. Without adequate professional help in dealing with the caregiving challenges they currently face and those that they are likely to face in the future, there is a risk that many of these older parents will relinquish some or all of their caregiving activities, which could have a negative impact on the well being of these families, and place additional strains on the formal mental health service system.

Social workers who work with these families need to be able to utilize evidence based interventions that have been shown to be effective in enabling these older parent caregivers to deal better with the variety of emotional and concrete challenges they experience. If researchers are successful in developing such evidence based interventions, social work practitioners will be able to help enrich the lives of these family caregivers as well as the lives of the sons and daughters for whom they care. The intervention described in this paper shows promise in improving the emotional well being and life satisfaction of aging parent caregivers of adult children with SMI, and in reducing the feelings of burden often reported by such parents. The researchers involved in the pilot study reported here are now engaged in planning and implementing a full-scale, methodologically rigorous efficacy test of this intervention. If this future research effort shows the intervention to be effective, social work practitioners who work with this population of caregivers will have a new approach to utilize in helping these parents to care for their SMI sons and daughters.

Footnotes

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (5R21AG26287-2)

References

- Abramowitz IA, Coursey RD. Impact of an educational support group on family participants who take care of their schizophrenic relatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:232–236. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baronet AM. Factors associated with caregiver burden in mental illness: a critical review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19(7):819–841. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C. Families of people with schizophrenia. In: Sartorius N, Leff J, Lopez-Ibor J, Maj M, Okasha A, editors. Families and mental disorders: From burden to empowerment. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson-Topps A, Hansson L. Quantitative and qualitative aspects of the social network in schizophrenic patients living in the community. Relationship to sociodemographic characteristics and clinical factors and subjective quality of life. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2001;47(1):67–77. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel DE. Families and psychiatric rehabilitation: Past, present and future. Social Security. Journal of Welfare and Social Security Studies. 1998;53(1):79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel DE, Robinson EM, Kennedy M. A review of empirical studies of interventions for families of persons with mental illness. In: Morrisey J, editor. Research in community mental health. Vol. 11. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 2000. pp. 87–130. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel DE, Schulz R. Caregiving and caregiver interventions in aging and mental illness. Family Relations. 1999;48(4):345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel DE, Song L, Chakravarthy V. Predictors of caregiver burden among support group members of persons with chronic mental illness. In: Kahana E, Biegel DE, Wykle ML, editors. Family caregiving across the lifespan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 178–215. [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M, Cochrane R. Families coping with schizophrenia: Coping styles, their origins and correlates. Psychological Medicine. 1990;20(4):857–865. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd RJ, Hughes ICT. What do carers of people with schizophrenia find helpful and unhelpful about psycho-education? Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 1997;4(2):118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger MW, Wandersman A, Goldman CR. Burdens and gratifications of caregiving: Appraisal of parental care of adults with schizophrenia. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):255–265. doi: 10.1037/h0079437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio L, Stevens A, Guy D, Roth DL, Haley WE. Impact of two psychosocial interventions on White and African American family caregivers of individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):568–579. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;52(1):685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FP, Greenberg JS. A positive aspect of caregiving: The influence of social support on caregiving gains for family members of relatives with schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40(5):423–435. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000040656.89143.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Solomon P, Draine J. Self-help groups for families of persons with mental illness: Perceived benefits of helpfulness. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35(1):15–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1018791824546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Lefley HP, Pickett S, Cohler B. Age and family burden among parents of offspring with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64(3):435–447. doi: 10.1037/h0079535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Pickett A. Age and family burden among parents residing with chronically mentally ill offspring. The Journal of Applied Social Sciences. 1987;12(1):79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins R, Davies AD, Turnbull CJ, Playfer JR. Assessing caregiving distress: A conceptual analysis and a brief scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41(4):387–403. doi: 10.1348/014466502760387506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J, Phillips JH. Family treatment with schizophrenia. In: Corcoran J, editor. Evidence-based social work practice with families: A lifespan approach. New York: Springer; 2000. pp. 428–501. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1976;128(3):280–289. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Lehman A. Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1995;21(4):631–643. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Marshall T, Seybolt D, Medoff D, Peer J, Leigh J, et al. Unmet needs of families of adults with mental illness and preferences regarding family services. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(6):655–662. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla, Goldfried MR. Problem solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1971;78(1):107–126. doi: 10.1037/h0031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu A. Social problem-solving in adults. In: Kendall PC, editor. Advances in cognitive-behavioral research and therapy. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla, Nezu AM. Problem-solving therapy. A social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein L. Brief treatment and new look at the task-centered approach. 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon IRH. Research on family interventions for mental disorders: Problems and perspectives. In: Sartorius N, Leff J, Lopez-Ibor J, Maj M, Okasha A, editors. Families and mental disorders: From burden to empowerment. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 235–258. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, McGill CW. Family care of schizophrenia. New York: The Guilford Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State:” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MB. Use of the Quality of Life Inventory in problem assessment and treatment planning for cognitive therapy of depression. In: Freeman A, Dattilio FM, editors. Comprehensive casebook of cognitive therapy. New York: Plenum; 1992. pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MB. Quality of life therapy and assessment in health care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5(1):19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW, Solano N, Ambler C, Rabinowitz Y, Thompson LW. Change in indices of distress among Latino and Anglo female caregivers of elderly relatives with dementia: Site-specific results from the REACH National Collaborative Study. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(3):580–591. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson DL, Steffen AM. Comparative effects of cognitive/behavioral and brief psychodynamic psychotherapies for the treatment of depression in family caregivers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(3):543–549. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron C, Poitras L, Dastoor DP, Perodeau G. Cognitive behavioral group intervention for spousal caregivers: Findings and clinical considerations. Clinical Gerontologist. 1996;17(1):3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Arnold JS, Fristad MA, Gavazzi SM. Family psychoeducation: Giving caregivers what they want and need. Family Relations. 1999;48(4):411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS. The other side of caring: Adult children with mental illness as supports to their mothers in later life. Social Work. 1995;40(3):414–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Greenley JR. Do mental health services reduce distress in families of people with serious mental illness? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1997;21(1):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Greenley JR, Benedict P. Contributions of person with serious mental illness to their families. Hospital Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(5):475–480. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM. Aging families of adults with schizophrenia: Planning for the future. A compilation of year one study findings. Greenbay, WI: Wisconsin Families and Mental Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield AB. Family Education in mental illness. New York: The Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield AB. Families of adults with severe mental illness: New directions in research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(2):254–260. doi: 10.1037/h0080229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield AB. Helping elderly caregivers plan for the future care of a relative with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2000;24(2):103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield AB, Lefley HP. Future involvement of siblings in the lives of persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41(3):327–338. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-5005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller T, Roccoforte J, Hsieh K, Cook J, Pickett S. Benefits of support groups for families of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(2):187–198. doi: 10.1037/h0080222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugen B. The effectiveness of a psychoeducational support service to families of persons with a chronic mental illness. Research on Social Work Practice. 1993;3(2):137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings J. Elderly parents as caregivers for their adult dependent children. Social Work. 1987;32(5):430–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LS, Roth D, Jones KP. Effect of demographic and behavioral variables on burden of caregivers of chronic mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46(2):141–145. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AV. Older parents who care for adult children with serious mental illness. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1998;29(4):35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AV, Adams JP, Jr., Campbell VA. Permanency planning by older parents who care for adult children with mental retardation. Mental Retardation. 1991;29(5):293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ. Recent developments in expressed emotion and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;160(5):601–620. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Research design in clinical psychology. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Kropf NP. Stigmatized and perpetual parents: Older parents caring for adult children with life-long disabilities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1995;24(1/2):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw TM, Coverdale JH, Falloon IRH, Kydd RR. Caregivers’ stresses when living together or apart from patients with chronic schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38(4):303–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1015949325141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefley HP. Aging parents as caregivers of mentally ill adult children: An emerging social problem. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1987;38(10):1063–1070. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefley HP. Family caregiving in mental illness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lefley HP. Family psychoeducation for serious mental illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lefley HP, Hatfield AB. Helping parental caregivers and mental health consumers cope with parental aging and loss. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(3):369–375. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens E, Thorning H, Herman D. Family psychoeducation in schizophrenia: Emerging themes and challenges. Journal of Practice in Psychiatry and Behavioral Health. 1999;5(6):314–325. [Google Scholar]

- Mengel MH, Marcus DB, Dunkle RE. “What will happen to my child when I’m gone?” A support and education group for aging parents as caregivers. The Gerontologist. 1996;36(6):816–820. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naleppa MJ, Reid WJ. Gerontological social work: A task-centered approach. New York: Columbia University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Washington, D.C.: Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office; Caring for people with severe mental disorders: A national plan of research to improve services. (DHHS Pub. No. (ADM)91-1762) 1991

- Noh S, Avisan WR. Spouses of discharged psychiatric patients: Factors associated with their experience of burden. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50(2):377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Norton W, Wandersman A, Goldman C. Perceived costs and benefits of membership in self-help groups: Comparisons of members and non-members of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Community Mental Health Journal. 1993;29(2):143–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00756340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn D, Mueser K. Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(5):607–617. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper B, Ryglewicz H. The young adult chronic patient: A new focus. The chronic mental patient: Five years later. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett S, Greenley JR. Off-timedness as a contributor to subjective burdens of offspring with severe mental illness. Family Relations. 1995;44(2):195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Platt S, Weyman A, Hirsch S, Hewett S. The Social Behavior Assessment Schedule (SBAS): Rational, contents, scoring and reliability of a new interview schedule. Social Psychiatry. 1980;15(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Horwitz AV. Caregiver burden: Differentiating the content and consequences of family caregiving. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57(3):741–751. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Gidron R. Parents of mentally ill adult children living at home. Health & Social Work. 2002;27(2):145–155. doi: 10.1093/hsw/27.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist. 1995;35(6):771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Krauss MW, Gordan RM, Judge K. Siblings of adults with mental retardation or mental illness: Effects on lifestyle and psychological well-being. Family Relations. 1997;46(4):395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P. Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47(12):1364–1370. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.12.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P. Interventions for families of individuals with schizophrenia: Maximising outcomes for their relatives. Disease Management and Health Outcomes. 2000;8(4):211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P, Draine J. Subjective burden among family members of mentally ill adults: Relation to stress, coping, and adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65(3):419–427. doi: 10.1037/h0079695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E. The impact of individualized and group workshop family education interventions on ill relative outcomes. Journal on Nervous Mental Disorders. 1996;184(4):252–254. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, Meisel M. Effectiveness of two models of brief family education: Retention of gains by family members of adults with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67(2):177–186. doi: 10.1037/h0080221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessler R, Gamache G. The family burden interview schedule – Short form (FBIS/SF) Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tessler R, Gamache G. Family experiences with mental illness. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Toseland RW, Blanchard CG, McCallion P. A problem solving intervention for caregivers of cancer patients. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;40(4):517–528. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winefield HR, Harvey EJ. Determinants of psychological distress in relatives of people with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1993;19(3):619–625. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation for Mental Health. Keeping care complete fact sheet: International findings. 2007 Http://www.wfmh.org/caregiver/docs/Keeping_care_complete_factsheet. Retrieved 6/24/2010.

- Zarit SH, Orr NK, Zarit JM. The hidden victims of Alzheimer’s disease: Families under stress. New York: University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Zarit JM. Cognitive impairment. In: Lewinsohn PM, Teri L, editors. Clinical geropsychology. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1983. pp. 38–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK, Suresky MJ. Relationships among perceived burden, depressive cognitions, resourcefulness, and quality of life in female relatives of seriously mentally ill adults. Issues In Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30(3):142–150. doi: 10.1080/01612840802557204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]