Abstract

Pseudomonas putida mt-2 harbors the TOL plasmid (pWWO), which contains the genes encoding the enzymes necessary to degrade toluene aerobically. The xyl genes are clustered in the upper operon and encode the enzymes of the upper pathway that degrade toluene to benzoate, while the genes encoding the enzymes of the lower pathway (meta-cleavage pathway) that are necessary for the conversion of benzoate to tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates, are encoded in a separate operon. In this study, the effects of oxygen availability and oscillation on the expression of catabolic genes for enzymes involved in toluene degradation were studied by using P. putida mt-2 as model bacterium. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was used to detect and quantify the expression of the catabolic genes xylM (a key gene of the upper pathway) and xylE (a key gene of the lower pathway) in cultures of P. putida mt-2 that were grown with toluene as a carbon source. Toluene degradation was shown to have a direct dependency on oxygen concentration, where gene expression of xylM and xylE decreased due to oxygen depletion during degradation. Under oscillating oxygen concentrations, P. putida mt-2 induced or downregulated xylM and xylE genes according to the O2 availability in the media. During anoxic periods, P. putida mt-2 decreased the expression of xylM and xylE genes, while the expression of both xylM and xylE genes was immediately increased after oxygen became available again in the medium. These results suggest that oxygen is not only necessary as a cosubstrate for enzyme activity during the degradation of toluene but also that oxygen modulates the expression of the catabolic genes encoded by the TOL plasmid.

BTEX (for benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes) compounds represent a large fraction of aromatic hydrocarbons in gasoline. In the last decades the fate and mineralization of these compounds in polluted environments have been intensively investigated due to the need for remediation strategies. Particularly, the microbial contribution to the removal of toluene from the environment is one of the most extensively studied processes within the field of BTEX bioremediation (1). Many bacteria and fungi have the potential to degrade toluene via diverse degradation pathways (18). The in situ degradation of many pollutants may, however, be affected by various environmental factors, such as the availability of nutrients and/or oxygen. Molecular oxygen is often reported to be a limiting factor for the degradation of contaminants in water and soil (17, 32), and seasonal or diurnal fluctuations of oxygen levels, as observed, e.g., in the rhizosphere, may temporarily limit bacterial toluene degradation rates (5, 22, 30).

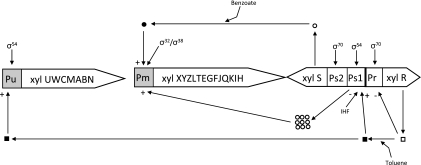

Pseudomonas putida mt-2 has been widely utilized in the past as a model organism for the study of aerobic toluene degradation. P. putida mt-2 harbors the TOL plasmid (pWWO), which contains the genes encoding the enzymes involved in toluene degradation (31), and the genes are organized into two operons (Fig. 1). The genes of the upper pathway (xylUWCMABN) encode the enzymes required for the conversion of toluene to benzoate. The genes of the lower pathway (xylXYZLTEGFJQKIH) that encode the enzymes for the degradation of benzoate to tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates are within a separate operon (3, 20). There are two key enzymes from each pathway; the xylene monooxygenase (XylMA), which catalyzes the hydroxylation of the methyl group of toluene and is the initial step of the upper pathway (24, 25, 33), and catechol-2,3-dioxygenase (C23O, XylE), which catalyzes the transformation of catechol to 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde within the lower pathway (14). Two proteins regulate gene transcription from the TOL plasmid; XylS and XylR, which activate the promoter of the lower or meta operon (Pm) and the upper operon (Pu), respectively. XylR positively regulates the σ54-depentent Pu promoter in the presence of toluene, p-xylene or m-xylene. XylS is activated by substrates formed from the upper pathway and stimulates the transcription of the operon from the corresponding Pm promoter. In addition, the XylR/effector (i.e., toluene) complex can increase XylS expression and subsequently hyper production of this regulator stimulates transcription from Pm even in the absence of effectors (20). The activation of the lower pathway not only needs the presence of a XylS/effector complex but also needs a heat-shock sigma factor (σ32) or a stationary σ38 factor, depending on the growth phase (13). It is therefore clear that the transcriptional regulation of genes involved in toluene degradation on the TOL plasmid are under the control of an intricate regulation system (6, 9, 28, 29); however, only a few studies have investigated the effect of oxygen on the expression of xyl genes (8, 28). It has been previously observed that a decrease in dissolved oxygen concentration has only a moderate effect on toluene degradation by P. putida mt-2 (11). Later, it was shown that the activity of benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase (BADH, XylB) and C23O increase when P. putida mt-2 is grown under conditions of carbon source saturation and oxygen limitation compared to carbon source limitation only (9). In addition, using microarray technology, Velazquez et al. (23) observed a complete repression of the xyl genes when oxic conditions were switched to anaerobic conditions in P. putida mt-2 cultures growing on m-xylene (28).

FIG. 1.

Operon structure and regulatory circuits controlling expression from the TOL plasmid pWWO. Symbols: squares, XylR; circles, XylS; open symbols, transcription regulator forms unable to stimulate transcription; closed symbols, forms able to stimulate transcription; +, stimulation of transcription; -, inhibition of transcription; IHF, integration host factor (for a review, see reference 21).

In the present study, we applied quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) to quantify the expression of xylM and xylE, which are genes encoding key enzymes involved in toluene degradation by P. putida mt-2, under different oxygen conditions. Gene expression was examined under both oxygen-limiting conditions, which may simulate conditions that could be found in soil or groundwater when contaminant degradation processes deplete oxygen, and under fluctuating oxygen conditions, which may simulate conditions such as those often found in environments such as the rhizosphere of plants. The results indicate not only that oxygen plays an important role in the expression of xyl genes but also that P. putida mt-2 is able to respond efficiently to temporal oscillations of oxygen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain and culture conditions.

The strain used in the present study was Pseudomonas putida mt-2, which harbors the TOL plasmid (pWWO). The experiments were carried out with mineral media (26). As an inoculum for kinetic experiments, P. putida mt-2 was grown aerobically in 50 ml of media in a 250-ml flask with 24 mM succinate as a carbon and energy source. Batch cultures with toluene were performed in 120-ml flasks with 50 ml of mineral medium. Inoculated cultures (107 cells ml−1) were incubated at 30°C in a rotary shaking incubator (145 rpm). For the batch cultures, all solutions were flushed with nitrogen to first create anoxic conditions, and then a desired volume of pure oxygen was injected into the flasks through gas-tight gray butyl Teflon-coated stoppers. In addition, toluene was injected to a concentration of 0.57 mM as the sole carbon and energy source. Negative controls without bacterial inoculation were run in parallel in order to monitor for abiotic processes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For the continuous fermentation experiments, a 5-liter reactor (Labfors small fermentor systems, Infors AG, Switzerland) with a working volume of 2 liters and controlled oxygen conditions was used (a scheme of the reactor set up is shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). During the fermentations, toluene was used as a sole carbon source, which was constantly added to the fermentor through a saturated gas stream. An external Schott flask filled with 200 ml of toluene (99.9%) was flushed constantly with air or nitrogen (0.6 liter min−1) accordingly in order to saturate the gas phase with toluene. By using a flow-meter, a constant flow of toluene was entering the reactor, keeping the concentration in the water phase at a constant level of 100 mg liter−1 (1.1 ± 0.1 mM measured in the liquid phase). In order to keep continuous oxic or anoxic conditions, air or nitrogen gas, respectively, was bubbled into the reactor from an extra gas source. The temperature used in all fermentation experiments was 30°C, with stirring at 300 rpm, and the pH was automatically set to 7.3 (adjusted with 5% H3PO4). The parameters monitored on-line by the reactor were: temperature, pH, percent dissolved oxygen (pO2), CO2, and exhausting O2, using Iris NT software (Infors AG, Switzerland). The measurements of pO2 were converted to mmol/liter units to make it comparable with the batch experiments. A feed bottle containing fresh mineral media was additionally prepared in order to keep bacteria growing constantly. When the bacteria in the fermentor reached an optical density at 560 nm (OD560) of 0.3 to 0.4 (3 × 108 to 4 × 108 cell ml−1), the bacteria were fed with fresh sterile media at a rate of 0.13 h−1 during the aerobic cycles and 0.0075 h−1 after 1 h of anaerobic conditions to avoid flushing out the cells. The same volume of culture was pumped out as waste to keep the volume of the reactor constant.

Analytical methods.

Toluene concentrations were measured by using gas chromatography coupled with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID): HP series HP6890 (Agilent Technology) equipped with an HP-5 column (30 m by 0.32 mm by 0.25-μm film thickness; Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA). The temperature program was as follows: 70°C for 2 min and then the temperature was increased by 30°C min−1 until reaching 260°C and held 2 min. The FID detection temperature was 250°C and helium was used as carrier gas. The injection was automated using an HP 612904 autosampler (Hewlett Packard). Liquid samples of 1 ml were taken from each culture flask or from the fermentor and injected in headspace vials, which were previously flushed with helium, amended with 50 μl of 50% H3PO4 to prevent further degradation, and closed with a Teflon-coated butyl rubber septum. Until the samples were measured, the vials were stored at −20°C. The concentration (mM) of toluene was subsequently plotted against time.

Oxygen measurements.

The concentration of oxygen in the medium and in the gas phase was measured by using planar oxygen sensor spots (Planar Oxygen Sensor Spot [PreSens GmbH, Regensburg, Germany]; Fibox 3 Oxygen Meter [PreSens GmbH]) (4, 21). At each sampling point, the dissolved oxygen concentration was registered every second during 1 min, and the results were displayed by using Oxy view-PsT3-V 5.41 software (PreSens GmbH).

ATP measurements.

One ml of cell suspension was added to 0.5 ml of ice-cold 1.3 M perchloric acid (23 mM EDTA) in 2-ml sterile Eppendorf tubes. After mixing, the cell extract was incubated for 30 min at 4°C and subsequently centrifuged at 9,300 × g for 15 min (4°C). Then, 1 ml of the supernatant was transferred into sterile Eppendorf tubes, and the pH was set to 7.5 by using a 0.72 M KOH (0.16 M KHCO3) solution. Again, the sample was centrifuged at 9,300 × g for 15 min (4°C), and 0.5 ml of the supernatant was stored at −20°C for later analysis. The ATP concentration in the cells was determined by using a luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence reaction (ATP Kit SL; BioThema, Handen, Sweden). In this reaction, light is formed from free ATP and luciferin by the enzyme luciferase from fireflies and measured in a Victor2 Wallac 1420 multilabel counter spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences GmbH, Germany). The data analysis was performed using Wallac 1420 Workstation Software (Wallac 1420 manager, version 2.00 [release 8]; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences GmbH, Germany). The photometer was equipped with two dispensers that were able to pump adjustable amounts of Tris-buffer and luciferin-luciferase solution into the wells of the microtiter plate, just before measurement of the samples (16).

RNA extraction.

RNA extraction from P. putida shake cultures and fermentor samples was performed by using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with some modifications. Grown cultures were vacuum filtered using 0.2-μm filters (PALL Corp., Port Washington, NY) in order to obtain ∼1010 cells on the filter. The filter with bacteria on it was washed with 2 ml of RNA protecting reagent (Qiagen). The buffer with the cells was centrifuged for 10 min at 5,900 × g. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was stored at −20°C until RNA was isolated. The pellet was resuspended in 700 μl of RLT buffer (Qiagen) containing 7 μl of β-mercaptoethanol, and transferred to a bead-beating tube, chilled on ice for 2 min, and mechanically lysed by using a FastPrep instrument (FastPrep FP120; Qbiogene, Inc., France) for 20 s at a speed setting of 6.0. The tubes were incubated on ice for 2 min and centrifuged for 1 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 600 μl of 70% ethanol was added. The mixture was transferred to an RNeasy column (Qiagen), and the washing and elution steps were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. To ensure that RNA was free of DNA contamination, an additional DNase treatment was performed after extraction by using a DNA-Free kit (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Darmstadt, Germany). The samples were stored at −20°C.

RNA quantification and cDNA synthesis.

In order to use an equal amount of total RNA to perform RT, quantification of the RNA was performed using the RiboGreen quantification reagent (Invitrogen GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT was performed using 100 ng of total RNA and an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen). Each reaction (20 μl) contained 2 μl of 10× buffer, 2 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (5 mM each), 1 μl of RNase inhibitor (10 U/μl), 2 μl of random hexamer primers (100 μM), and 1 μl of Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen). For each sample, a reaction without reverse transcriptase was performed as a control for possible DNA contamination.

Relative quantification using qRT-PCR.

A relative quantification method was used to analyze changes in gene expression in a given sample with respect to another reference sample. Relative increases or decreases in gene expression compared to a baseline level in time were determined, allowing quantification without the necessity for an absolute standard curve. The 2−ΔΔCT method (12) described in equation 1 was used since the amplification efficiencies of the different primer pairs were at least 95% and no significant differences were observed using the relative-fold method (19). A reference gene should be selected for normalization of target gene expression to compensate for intersample variation. In the present study, the 16S rRNA gene was used as a reference gene, and the expression of two catabolic genes involved in toluene degradation by P. putida mt-2 (target genes) were monitored over time (zero hour sample as calibrator). The efficiency (E) of the reaction was determined by using a calibration curve of a dilution series of cDNA (no quantification is needed). The efficiency of one cycle reaction should be calculated in the exponential phase of amplification using the expression E = 10(−1/slope).

|

(1) |

Primer design and qPCRs.

Different sets of primers were designed using the Primer3 program (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi) to target the xylM, xylE, and 16S rRNA genes of P. putida mt-2. After optimization of the annealing temperatures in order to obtain appropriate PCR efficiencies and to test the specificity of the different primers, the three sets of oligonucleotides presented in Table 1 were selected for application in the present study. SYBR green was used as a fluorescent dye for monitoring PCR amplification of targets in real time and was present in the commercial reaction buffer RT2 qPCR master mix (SA Biosciences, Maryland). A PCR mix of 25 μl consisted of: 12.5 μl of 2× RT2 qPCR master mix, 0.5 μl of the forward and reverse primers (final concentration, 0.2 μM), 10.5 μl of double-distilled H2O, and 1 μl of template (cDNA). Thermal cycling conditions for the selected primers were as follows: an initial cycle of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and an annealing step for 60 s (data acquisition step), followed by 1 cycle at 95°C for 15 s and 55°C, and then 80 cycles from 55°C for 10 s, increasing 0.5°C cycle−1 (melting curve). Triplicates of each sample were loaded in a 96-well plate, and the standard deviation was calculated. To control for any possible DNA contamination of the RNA samples, a cDNA reaction without reverse transcriptase (as described above) was performed for each run. Six blanks (no template controls) containing only the PCR master mix were also included in each experiment. After the qPCR, 5 μl of sample was loaded on a 2% agarose gel to analyze the size of the obtained products and to check for any contamination present in negative controls or blanks, in addition to the melting-curve analyses. Further details about the validation of the designed primer sets are found in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences designed for this study to amplify fragments of xylM, xylE, and 16S rRNA of P. putida mt-2 by using qRT-PCR

| Target | Primer | Orientationa | Sequence (5′-3′) | Ta (°C)b | Expected product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| xylM | Tol-912 | F | GAT GCC TTC GCT CTT TGT GT | 58 | 115 |

| Tol-Rc | R | CTC ACC TGG AGT TGC GTA C | |||

| xylE | C230-F | F | CGA CCT GAT CTC CAT GAC CGA | 62 | 147 |

| xyle-834 | R | TTT GTG GTC CGG GTA GTT GT | |||

| 16S rRNA | 16S-493 | F | TAG AGA GGG TGC AAG CAT TA | 60 | 113 |

| 16S-606 | R | GCC AGT TTT GGA TGC AGT TC |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Ta, annealing temperature used during real-time PCR.

From Baldwin et al. (4a).

RESULTS

The expression of the catabolic genes xylM and xylE of P. putida mt-2 was monitored while the cells were provided with different oxygen concentrations, as well as oxygen fluctuations. qRT-PCR in combination with the relative quantification approach was used in the present study. The catabolic genes and the 16S rRNA of P. putida were targeted by the specific primers detailed in Table 1. The preliminary validation experiments used to select the appropriate sets of primers for application here are presented in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

Effect of oxygen availability on catabolic gene expression of Pseudomonas putida mt-2.

The effect of limited oxygen availability on growth, toluene degradation, and TOL plasmid gene expression was studied in batch cultures of P. putida mt-2 with 0.57 mM toluene as the sole carbon and energy source. Different initial oxygen concentrations from oxic (21% in gas phase = 8.35 mmol O2/liter) to hypoxic (0.87% = 0.01 mmol O2/liter) conditions were adjusted according to the method of Rosell et al. (21) by injecting pure oxygen into anoxic flasks (21). In addition, anoxic cultures (0% O2) were studied. Abiotic controls without inoculated bacteria were prepared for the three oxygen-limiting conditions (0.87, 2.40, and 4.15% O2 saturation in the gas phase) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

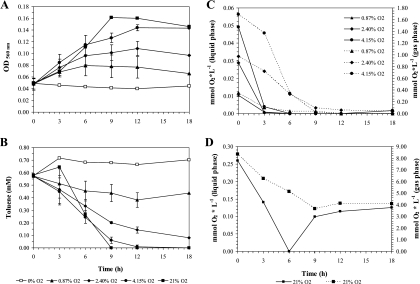

The growth curves revealed a direct dependency of P. putida mt-2 on oxygen to grow with toluene as the carbon source (Fig. 2A). Consequently, toluene degradation rates were also strongly affected by the initial availability of oxygen (Fig. 2B). Whereas toluene was completely degraded at 4.15 and 21% of O2 saturation, only ca. 20 or 85% of the toluene was consumed in cultures provided with 0.87 or 2.40% oxygen saturation, respectively. No toluene degradation was observed under anoxic conditions (Fig. 2B). Oxygen concentrations were monitored in both the gas and the liquid phases in order to determine when oxygen was not available for the cells anymore, as well as to calculate absolute oxygen consumption. Dissolved oxygen concentrations decreased rapidly after starting the experiment in all tested conditions (Fig. 2C and D). The values of dissolved oxygen observed in the corresponding abiotic controls (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) indicate that bacterial oxygen consumption occurred faster than the diffusion of oxygen into the liquid phase. Cultures grown in the presence of 4.15 or 0.87% O2 initially consumed all oxygen after 12 h. Cultures grown at the intermediate concentration (2.40%) initially showed a slower oxygen consumption rate, and at the end of the experiment (18 h) 0.04 mmol/liter of oxygen was still present in the gas phase, but no oxygen was detected in the liquid phase. Cultures grown at atmospheric conditions (21%) initially consumed all oxygen to below the detection limit after 6 h (Fig. 2D), likely due to rapid consumption by the bacteria and resulting disequilibrium between the gas and liquid phase. However, the oxygen increased again after 9 h of incubation when toluene was completely degraded (Fig. 2B). Afterward, oxygen concentrations reached equilibrium between the gas and the liquid phase until the end of the experiment (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Effect of different initial oxygen concentrations (0, 0.87, 2.40, 4.15, and 21% oxygen in the gas phase) on growth (OD560) (A), toluene degradation (B), and gas phase (C) (dashed lines) and dissolved (solid lines) oxygen concentrations in P. putida mt-2 cultures growing with toluene as a carbon source. (D) Oxygen concentrations in the gas phase (dashed line) and dissolved oxygen concentration (solid lines) in the fully oxic cultures (21%). Due to big differences in the scale range, oxygen concentrations for the fully oxic cultures (21%) are presented in panel D. The errors bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

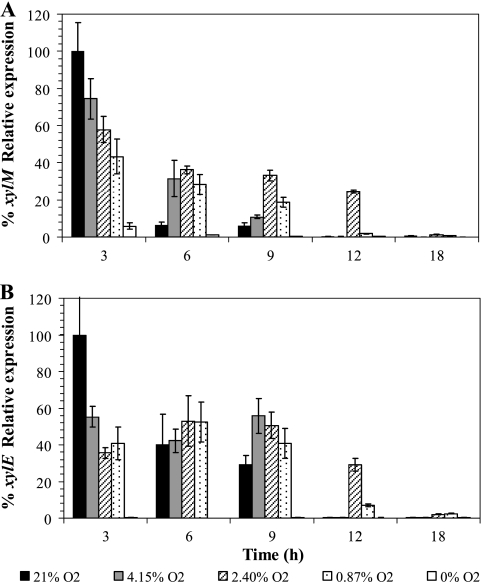

The relative expression of the catabolic genes xylM and xylE in response to oxygen availabilities is shown in Fig. 3. The relative expression values obtained at time zero hours were used as a calibrator value. The results are presented as the percentage of expression with respect to the highest relative expression value. At the highest oxygen concentrations (21 and 4.15%), the expression of xylM was not detected after 12 h of incubation, when toluene was already completely consumed. In the case of the lower oxygen concentrations (2.40 and 0.87%), the expression of the upper pathway gene (xylM) strongly decreased after 12 and 18 h of incubation for 2.40 and 0.87% oxygen, respectively, although a significant amount of toluene was still present in the flasks. At anoxic conditions (0% O2) a slight expression of xylM was observed at the beginning of the experiment. However, after 6 h of incubation and until the end of the experiment the expression of this gene was not detected. In the case of xylE, higher gene expression was observed at oxic conditions only at the beginning of the experiment compared to other tested conditions. Further, the expression levels for xylE were similar for the different oxygen concentration treatments. After 12 h, no expression of xylE was detected in the flasks amended with 4.15 or 21% O2, and a drastic decrease in gene expression was observed after 18 h for the 2.40 and 0.87% oxygen treatments. In the presence of anoxic conditions no expression was detected.

FIG. 3.

Effect of different initial oxygen concentrations (0, 0.87, 2.40, 4.15, and 21% oxygen in the gas phase) on xylM (A) and xylE (B) expression. The gene expression (relative to the 0-h sample) is expressed as a percentage of the highest value. Each sampling point corresponds to an independent flask. The errors bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

Effect of oxygen oscillations on catabolic gene expression in P. putida mt-2. (i) Batch cultures.

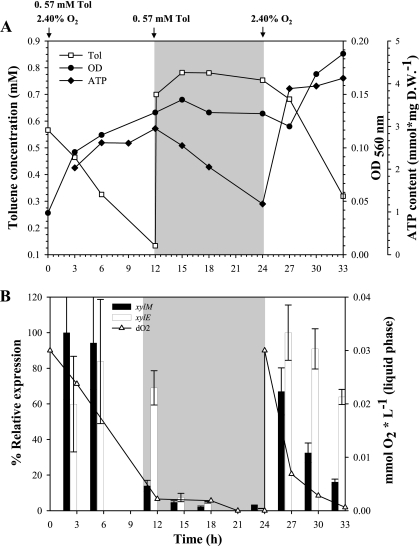

In order to determine the effect of oxygen oscillations on catabolic gene expression in P. putida mt-2 growing on 0.57 mM toluene as a carbon source, cultures were subjected to oxic and anoxic cycles in batch cultures. Oxygen was injected to establish an oxygen concentration of 2.40% in the gas phase. This concentration represents oxygen-limiting conditions according to the previous experiments detailed above (Fig. 2). After 12 h of incubation, the cultures were respiked with toluene to avoid starvation, but no oxygen was injected. Consequently, oxygen-limiting conditions arose in which toluene was still present as a carbon source. Toluene degradation and cell growth stopped after 12 h until oxygen was injected again (to create an oxygen concentration of 2.40% in the gas phase) into the flasks after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 4A). The expression of xylM showed a significant decrease after 12 h, while for xylE this effect was delayed until 15 h of incubation. Both catabolic genes were expressed at low levels until the sampling point at the 24th hour (Fig. 4B). When the flasks were respiked with oxygen, both catabolic genes were immediately upregulated, the degradation of toluene and growth resumed, and the oxygen concentration in the liquid media rapidly decreased (Fig. 4B). In order to monitor the energy status of the cells during the oscillation in oxygen concentrations, the cellular ATP content was measured (Fig. 4A). A slow increase of ATP was observed during the first 12 h of incubation, while afterward it decreased, but the values were never lower than 1 nmol/mg (dry weight). Once oxygen was respiked in the bottles, a fast increase in the ATP level was observed and was stable until the end of the experiment.

FIG. 4.

Response of P. putida mt-2 to oxygen oscillation in shake cultures. (A) Effect of oxygen oscillations on growth, toluene consumption, and ATP content. (B) Relative gene expression of xylM and xylE, and dissolved oxygen concentrations during simulation of diurnal cycles of oxygen. OD, optical density; Tol, toluene. Pure oxygen was injected through the gas phase. The injection points for toluene and oxygen are indicated by arrows on the top of the figure. The gray-shaded areas indicate oxygen-limiting conditions during the experiment. The errors bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

(ii) Continuous experiments in a fermentor.

In order to obtain continuous controlled oxygen and toluene concentrations, a continuous culture of P. putida mt-2 was set up in a 5-liter fermentor (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Diurnal cycles of oxygen were simulated, i.e., two aerobic/anaerobic cycles that were maintained for several hours each. Bacteria were continuously fed with toluene as a carbon source (1.1 ± 0.1 mM, measured in the liquid phase), which was provided as saturated air phase to create aerobic conditions in the reactor or as toluene saturated nitrogen gas stream for anaerobic conditions. A dilution rate of 0.13 h−1 was applied during the aerobic periods and 0.0075 h−1 during the anoxic cycles.

After 6 h of incubation in the presence of oxic conditions, an exponential increase in CO2 concentrations in the exhaust gas was observed, indicating bacterial growth (μ = 0.10 h−1). Simultaneously, toluene degradation was observed (Fig. 5A). During the first anoxic period (t = 20 to 26 h), a drastic decrease in CO2 production, as well as toluene degradation, was observed, suggesting a cessation of bacterial activity and growth. Similar effects were observed in the second anaerobic cycle (t = 44 to 49 h). In both cases, once oxic conditions were restored the growth continued at the same rate as under oxic conditions (μ = 0.10 h−1) according to increases in the ODs, while the CO2 production recovered rapidly, and toluene concentration in the media decreased once again. During oxic conditions, P. putida mt-2 cells rapidly consumed oxygen when CO2 increased exponentially (Fig. 5A). Although air was constantly supplied during the oxic cycles, bacteria consumed oxygen at high rates, which resulted in low dissolved oxygen concentrations.

FIG. 5.

Response of P. putida mt-2 to oxygen oscillation in continuous fermentation. (A) %CO2 as a growth parameter and toluene concentration. (B) Relative gene expression of xylM and xylE, and dissolved oxygen concentrations during simulation of diurnal cycles of oxygen. The gray-shaded areas indicate anoxic conditions during the experiment. The errors bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

The relative gene expression of the catabolic genes xylM and xylE was monitored using the 0-h time point as calibrator (Fig. 5B). As soon as airflow was switched to nitrogen, thereby creating anoxic conditions, the levels of gene expression decreased significantly and immediately in the case of xylM; however, for xylE the response was slower. When aerobic conditions were restored, bacteria quickly responded, and the gene expression increased again.

DISCUSSION

The degradation of toluene by P. putida mt-2 was highly dependent on oxygen availability as shown in Fig. 2, which has been previously described (11). In the present study, absolute amounts of oxygen and not only dissolved oxygen concentrations were taken into account in order to provide a more detailed description of the experimental systems. Oxygen concentrations decreased rapidly in the headspace and liquid phase in all tested conditions when P. putida mt-2 was present, which indicates that bacterial consumption occurred much faster than oxygen transfer into the liquid phase. Except for cultures grown under “fully” oxic conditions (21%), all other oxygen concentrations corresponded to oxygen-limiting conditions considering the following stoichiometric equation for toluene mineralization: C7H8 + 9O2 → 7CO2 + 4H2O (this means 5.13 mM oxygen would be required for the degradation of 0.57 mM toluene). However, in the presence of 4.15% oxygen, toluene (0.57 mM) was also completely consumed by the end of the experiment (Fig. 2B). According to the stoichiometric equation for toluene mineralization, the oxygen concentration available under this condition would only lead to partial degradation of the toluene to further intermediates such as catechol or 2-hydroxy-cis,cis-muconate semialdehyde. Partial degradation and excretion of degradation intermediates has been described in P. putida mt-2 growing on benzoate under oxygen-limiting conditions (2). However, it must also be taken into consideration that toluene is only partially mineralized because of bacterial biomass production, thus allowing complete disappearance of toluene in the presence of lower oxygen concentrations.

The different oxygen availabilities also had an effect on the expression of catabolic genes harbored on the TOL plasmid. In the general gene regulation scheme proposed for the TOL plasmid (20), the presence or absence of the substrate and subsequent intermediates are the main controllers of the system. This was clearly observed in samples in the presence of “fully” oxic conditions or amended with 4.15% oxygen. However, according to our results, lower oxygen availabilities had an effect on gene expression of catabolic genes from the TOL plasmid as well. In the presence of lower oxygen concentrations (0.87 and 2.40% O2), bacteria face different conditions, where at the end of the experiment oxygen was almost completely consumed, but toluene was still present in the media as an inducer of the catabolic pathway. The effect observed for both catabolic genes (xylM and xylE) was comparable at the lower oxygen concentrations. The gene expression profiles indicated that under a certain threshold concentration of oxygen in the gas phase, which seems to be ca. 0.04 mmol O2/liter, bacteria strongly decrease the expression of the xyl genes, even though the inducer toluene was still present in the media at high concentrations. These results strongly suggest that a certain concentration of oxygen is required to keep the upper pathway of the TOL plasmid induced. Thus, oxygen is not only necessary as a cosubstrate for enzymatic activity during degradation of toluene but also acts as a controller for the expression of the catabolic genes encoded by the TOL plasmid. The same effect was observed in the case of the lower pathway gene xylE, but to a lesser extent. The threshold of oxygen concentration observed in the present study was close to reported half saturation constants (Kdo) of hydroxylases and dioxygenases in several Pseudomonas species (0.04 to 0.07 mmol O2/liter) (23) but much higher than the values reported for the C23O, which is encoded by the TOL plasmid (1.2 × 10−4 mmol O2/liter) (10). These differences in oxygen affinities of the enzymes could explain the remarkable effect of a residual oxygen concentration of 0.04 mmol O2/liter on xylM expression rather than on xylE expression.

An unexpected result was that a slight upregulation of xylM (<10% compared to oxic conditions) was observed after 3 h of incubation at anoxic conditions, but no further significant expression was detected. Previously, Velazquez et al. (23) observed that the transfer from aerobic to anaerobic conditions inhibited the expression of xyl genes in P. putida cells growing on m-xylene (28). This discrepancy with our results could possibly be due to the different setup of both experiments. In our case, P. putida was grown with succinate as a carbon source before being transferred into an anoxic media containing toluene as a carbon source, whereas Velazquez et al. (23) grew bacteria permanently on m-xylene. Toluene, as the main inducer of the TOL pathway, is sensed by P. putida cells as a new carbon source, and this caused the upregulation xylM during the first hours, even when oxygen was lacking. However, since oxygen was not present in the system the induction of xylM is more than 10 times lower compared to fully oxic conditions.

In the experiments with oxygen oscillations, in batch cultures, as well as in continuous fermentation experiments, P. putida mt-2 was able to modulate the expression of the catabolic TOL genes according to the presence or absence of oxygen in the media (Fig. 4B and 5B). As soon as oxygen limitation occurred but toluene was still available, the expression of the xylM and xylE genes decreased. When oxygen was present again, fast recovery of gene expression occurred. P. putida mt-2 has been shown to be at a disadvantage when cultivated in competition with other toluene-degrading bacteria under oxygen-limiting conditions (7). In spite of these observations, our results indicate that this strain presented a physiological fitness under unfavorable conditions regarding oxygen availability and was able to modulate the expression of catabolic genes depending on the oxygen availability.

Previous chemostat studies with strain mt-2 have shown an increase in the enzymatic activities of BADH and C23O when cells growing under m-xylene limiting conditions were switched to nonlimiting carbon source conditions plus a reduction in oxygen concentration from 21 to 4% (9). This is in disagreement with our results, and may be because a switch from high to low oxygen concentration produces a different effect than the depletion of low oxygen concentrations during degradation. However, in our study comparable findings to those of Duetz et al. (9) were observed at the 9-h sample point in the batch experiment (Fig. 3A). At this point, the fully oxic culture (21%) is only limited by carbon, since the oxygen concentration available is much higher than necessary to degrade the toluene present in the media. Under such conditions, the expression of both catabolic genes is lower than the expression observed under 2.40 or 0.87% oxygen, where the carbon source is nonlimiting compared to the concentrations of available oxygen.

It has been suggested that the cellular energy status could play a key role under oxygen-limiting conditions (8), which could explain the observed decrease in gene expression. However, we have shown that after 12 h under oxygen-limiting conditions a relatively high ATP content of 1.2 nmol ATP mg−1 (dry weight) was measured (Fig. 4A). Recently, it was described that the ATP content correlates with the “energy charge” in cells of P. putida, and therefore the cellular ATP content can be used as an indicator for the cellular energetic state, as well as for the amount of active biomass (16). Thus, our study showed that a decrease in the expression of xylM and xylE was not directly related to a decline in the ATP content of cells, which was not dramatically decreased.

The main focus of the present study was to describe the response of catabolic genes of P. putida mt-2 to different oxygen availabilities and oscillating conditions. The results presented here provide the first indications that P. putida mt-2 possesses a regulation system that modulates the expression of catabolic genes according to the oxygen availability in addition to substrate induction. The presence of the anaerobic transcriptional regulator Anr in the genome of P. putida KT2440 (or the TOL plasmid-cured derivative of P. putida mt-2) (15), and its described role of coordinating the levels of different terminal oxidases in P. putida as a response to oxygen availability (27) also supports this hypothesis. The oxygen concentrations necessary to induce the transition between the inactive to the active transcriptional form of the fumarate and nitrate reduction (FNR) system, the Anr counterpart in E. coli, are between 0.001 and 0.006 mmol of O2/liter (2). Thus, these concentrations are ∼10 times lower than the oxygen concentration observed as the threshold oxygen concentration obtained for xyl gene expression in our experiments. However, this does not mean that Anr is not involved in O2 sensing in P. putida and perhaps in the regulation of catabolic genes such as xylM and xylE, because it has also been postulated that Anr molecules are able to bind to high-affinity sites in the presence of higher oxygen concentrations (27). Further research on the different genes regulated by the ANR system would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Our results reveal that xyl gene expression in P. putida mt-2 is dependent on oxygen availability, which is not related to the energy status of the cells, and suggests that a sensing-regulation system is involved. This oxygen-dependent modulation of xyl gene expression is most likely an adaptive response mechanism that has evolved to enable the bacterium to respond quickly to changes in oxygen concentrations that may occur in situ, e.g., especially when oxygen is reintroduced into an environment after periods of anoxia.

The findings presented here provide new knowledge about the response of pollutant-degrading bacteria to different concentrations and fluctuations of oxygen that may occur in situ. Further investigations will focus on the modulation of catabolic gene expression in more complex systems, simulating naturally occurring oxygen gradients and oscillation, e.g., in planted systems such as constructed wetlands.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Clara García, Alejandro Sarrión, and Fabrizio Lecce for their useful help in the experiments, as well as Steffi Hunger and Karin Lange for their technical support during the fermentation experiments and ATP measurements. We thank Mónica Rosell (Department of Isotope Biogeochemistry, UFZ, Leipzig, Germany) for her important contribution and support during the oxygen measurements. We also thank Kenneth Wasmund for critically reading the manuscript regarding grammar. We thank Gabriele Diekert (Institute for Microbiology, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Germany) for critical and helpful discussion of this work.

This study was partially supported by a collaborative project (BACSIN, contract no. 211684) from the European Commission within its Seventh Framework Program and by the Marie Curie Early Stage Researchers (MEST-CT-2004-8332) project AXIOM within its Sixth Framework Program.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agteren, M. H. V., S. Keuning, and D. B. Janssen. 1998. Handbook on biodegradation and biological treatment of hazardous organic compounds, p. 243-255. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands.

- 2.Arras, T., J. Schirawski, and G. Unden. 1998. Availability of O2 as a substrate in the cytoplasm of bacteria under aerobic and microaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 180:2133-2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assinder, S. J., and P. A. Williams. 1990. The TOL plasmids: determinants of the catabolism of toluene and the xylenes. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 31:1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balcke, G. U., S. Wegener, B. Kiesel, D. Benndorf, M. Schlomann, and C. Vogt. 2008. Kinetics of chlorobenzene biodegradation under reduced oxygen levels. Biodegradation 19:507-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Baldwin, B. R., C. H. Nakatsu, and L. Nies. 2003. Detection and enumeration of aromatic oxygenase genes by multiplex and real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3350-3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brune, A., P. Frenzel, and H. Cypionka. 2000. Life at the oxic-anoxic interface: microbial activities and adaptations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:691-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominguez-Cuevas, P., J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, S. Marques, J. L. Ramos, and V. de Lorenzo. 2006. Transcriptional tradeoff between metabolic and stress-response programs in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 cells exposed to toluene. J. Biol. Chem. 281:11981-11991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duetz, W. A., C. de Jong, P. A. Williams, and J. G. van Andel. 1994. Competition in chemostat culture between Pseudomonas strains that use different pathways for the degradation of toluene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2858-2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duetz, W. A., S. Marques, B. Wind, J. L. Ramos, and J. G. van Andel. 1996. Catabolite repression of the toluene degradation pathway in Pseudomonas putida harboring pWWO under various conditions of nutrient limitation in chemostat culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:601-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duetz, W. A., B. Wind, M. Kamp, and J. G. van Andel. 1997. Effect of growth rate, nutrient limitation and succinate on expression of TOL pathway enzymes in response to m-xylene in chemostat cultures of Pseudomonas putida (pWWO). Microbiology 143:2331-2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kukor, J. J., and R. H. Olsen. 1996. Catechol 2,3-dioxygenases functional in oxygen-limited (hypoxic) environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1728-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leahy, J. G., and R. H. Olsen. 1997. Kinetics of toluene degradation by toluene-oxidizing bacteria as a function of oxygen concentration, and the effect of nitrate. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 23:23-30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marques, S., M. Manzanera, M. M. Gonzalez-Perez, M. T. Gallegos, and J. L. Ramos. 1999. The XylS-dependent Pm promoter is transcribed in vivo by RNA polymerase with σ32 or σ38 depending on the growth phase. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1105-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakai, C., H. Kagamiyama, M. Nozaki, T. Nakazawa, S. Inouye, Y. Ebina, and A. Nakazawa. 1983. Complete nucleotide sequence of the metapyrocatechase gene on the TOI plasmid of Pseudomonas putida mt-2. J. Biol. Chem. 258:2923-2928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson, K. E., C. Weinel, I. T. Paulsen, R. J. Dodson, H. Hilbert, V. A. Martins dos Santos, D. E. Fouts, S. R. Gill, M. Pop, M. Holmes, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, R. T. DeBoy, S. Daugherty, J. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. Nelson, O. White, J. Peterson, H. Khouri, I. Hance, P. C. Lee, E. Holtzapple, D. Scanlan, K. Tran, A. Moazzez, T. Utterback, M. Rizzo, K. Lee, D. Kosack, D. Moestl, H. Wedler, J. Lauber, D. Stjepandic, J. Hoheisel, M. Straetz, S. Heim, C. Kiewitz, J. A. Eisen, K. N. Timmis, A. Dusterhoft, B. Tummler, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 4:799-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann, G., S. Cornelissen, F. van Breukelen, S. Hunger, H. Lippold, N. Loffhagen, L. Y. Wick, and H. J. Heipieper. 2006. Energetics and surface properties of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E in a two-phase fermentation system with 1-decanol as second phase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4232-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen, R. H., M. D. Mikesell, J. J. Kukor, and A. M. Byrne. 1995. Physiological attributes of microbial BTEX degradation in oxygen-limited environments. Environ. Health Perspect 103(Suppl. 5):49-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parales, R. E., J. V. Parales, D. A. Pelletier, and J. L. Ditty. 2008. Diversity of microbial toluene degradation pathways. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 64:1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaffl, M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos, J. L., S. Marques, and K. N. Timmis. 1997. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid catabolic operons is achieved through an interplay of host factors and plasmid-encoded regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:341-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosell, M., S. Finsterbusch, S. Jechalke, T. Hubschmann, C. Vogt, and H. H. Richnow. 2010. Evaluation of the effects of low oxygen concentration on stable isotope fractionation during aerobic MTBE biodegradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44:309-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleh-Lakha, S., M. Miller, R. G. Campbell, K. Schneider, P. Elahimanesh, M. M. Hart, and J. T. Trevors. 2005. Microbial gene expression in soil: methods, applications and challenges. J. Microbiol. Methods 63:1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaler, T. A., and G. M. Klecka. 1986. Effects of dissolved oxygen concentration on biodegradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:950-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw, J. P., and S. Harayama. 1992. Purification and characterisation of the NADH:acceptor reductase component of xylene monooxygenase encoded by the TOL plasmid pWWO of Pseudomonas putida mt-2. Eur. J. Biochem. 209:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki, M., T. Hayakawa, J. P. Shaw, M. Rekik, and S. Harayama. 1991. Primary structure of xylene monooxygenase: similarities to and differences from the alkane hydroxylation system. J. Bacteriol. 173:1690-1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tschech, A., and G. Fuchs. 1987. Anaerobic degradation of phenol by pure cultures of newly isolated denitrifying pseudomonads. Arch. Microbiol. 148:213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ugidos, A., G. Morales, E. Rial, H. D. Williams, and F. Rojo. 2008. The coordinate regulation of multiple terminal oxidases by the Pseudomonas putida ANR global regulator. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1690-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velazquez, F., V. de Lorenzo, and M. Valls. 2006. The m-xylene biodegradation capacity of Pseudomonas putida mt-2 is submitted to adaptation to abiotic stresses: evidence from expression profiling of xyl genes. Environ. Microbiol. 8:591-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velazquez, F., V. Parro, and V. de Lorenzo. 2005. Inferring the genetic network of m-xylene metabolism through expression profiling of the xyl genes of Pseudomonas putida mt-2. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1557-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiessner, A., U. Kappelmeyer, P. Kuschk, and M. Kastner. 2005. Influence of the redox condition dynamics on the removal efficiency of a laboratory-scale constructed wetland. Water Res. 39:248-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams, P. A., and K. Murray. 1974. Metabolism of benzoate and the methylbenzoates by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for the existence of a TOL plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 120:416-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson, L. P., and E. J. Bouwer. 1997. Biodegradation of aromatic compounds under mixed oxygen/denitrifying conditions: a review. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18:116-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worsey, M. J., and P. A. Williams. 1975. Metabolism of toluene and xylenes by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for a new function of the TOL plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 124:7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.