Abstract

We isolated three Sphingobium fuliginis strains from Phragmites australis rhizosphere sediment that were capable of utilizing 4-tert-butylphenol as a sole carbon and energy source. These strains are the first 4-tert-butylphenol-utilizing bacteria. The strain designated TIK-1 completely degraded 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylphenol in basal salts medium within 12 h, with concomitant cell growth. We identified 4-tert-butylcatechol and 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone as internal metabolites by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. When 3-fluorocatechol was used as an inactivator of meta-cleavage enzymes, strain TIK-1 could not degrade 4-tert-butylcatechol and 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone was not detected. We concluded that metabolism of 4-tert-butylphenol by strain TIK-1 is initiated by hydroxylation to 4-tert-butylcatechol, followed by a meta-cleavage pathway. Growth experiments with 20 other alkylphenols showed that 4-isopropylphenol, 4-sec-butylphenol, and 4-tert-pentylphenol, which have alkyl side chains of three to five carbon atoms with α-quaternary or α-tertiary carbons, supported cell growth but that 4-n-alkylphenols, 4-tert-octylphenol, technical nonylphenol, 2-alkylphenols, and 3-alkylphenols did not. The rate of growth on 4-tert-butylphenol was much higher than that of growth on the other alkylphenols. Degradation experiments with various alkylphenols showed that strain TIK-1 cells grown on 4-tert-butylphenol could degrade 4-alkylphenols with variously sized and branched side chains (ethyl, n-propyl, isopropyl, n-butyl, sec-butyl, tert-butyl, n-pentyl, tert-pentyl, n-hexyl, n-heptyl, n-octyl, tert-octyl, n-nonyl, and branched nonyl) via a meta-cleavage pathway but not 2- or 3-alkylphenols. Along with the degradation of these alkylphenols, we detected methyl alkyl ketones that retained the structure of the original alkyl side chains. Strain TIK-1 may be useful in the bioremediation of environments polluted by 4-tert-butylphenol and various other 4-alkylphenols.

4-tert-Butylphenol is an alkylphenol with a tertiary branched side chain of four carbon atoms at the para position of phenol. It is an industrially important chemical and is abundantly and widely used for the production of phenolic, polycarbonate, and epoxy resins. Production of 4-tert-butylphenol in the European Union in 2001 was 25,251 tons (t) (9). In Japan, according to the National Institute of Technology and Evaluation (http://www.safe.nite.go.jp/english/sougou/view/ComprehensiveInfoDisplay_en.faces), production of 4-tert-butylphenol amounted to 27,761 t in 2007. 4-tert-Butylphenol is widely distributed in aquatic environments, including river waters (20), seawaters (17), river sediments (17), marine sediments (23), and effluent samples from sewage treatment plants and wastewater treatment plants (22). Furthermore, 4-tert-butylphenol interacts with estrogen receptors (29, 30, 34, 35, 39) and exhibits other toxic effects on aquatic organisms and humans (4, 15, 16, 25, 26, 42, 43). Therefore, it is necessary to study the biodegradation of 4-tert-butylphenol to understand its fate in the aquatic environment, to establish technologies to treat the waters polluted by it, and to remove it from contaminated environments.

Studies of the biodegradation of alkylphenols have focused mainly on branched 4-nonylphenol. Several strains of sphingomonad bacteria, including Sphingomonas sp. strain TTNP3 (38), Sphingobium xenophagum Bayram (11), and Sphingomonas cloacae S-3T (10), have recently been isolated from activated sludge. These strains can degrade branched 4-nonylphenol and utilize it as a sole carbon source. In addition, several Pseudomonas strains that can degrade medium-chain 4-n-alkylphenols (e.g., 4-n-butylphenol) and utilize them as sole carbon sources have been isolated from activated sludge or contaminated soil; they include Pseudomonas veronii INA06 (1), Pseudomonas sp. strain KL28 (21), and Pseudomonas putida MT4 (36). Biodegradation of branched 4-nonylphenol and 4-n-butylphenol has been well studied, but little is known about the biodegradation of 4-tert-butylphenol, although this compound has a structure similar to those of branched 4-nonylphenol and 4-n-butylphenol. There is only one report on the biotransformation of 4-tert-butylphenol—by resting cells of S. xenophagum strain Bayram grown on technical nonylphenol—but this strain cannot grow on 4-tert-butylphenol (11, 14). To our knowledge, there are no reports of bacteria that utilize 4-tert-butylphenol as the sole carbon source, and the biochemical pathway of 4-tert-butylphenol utilization has not been described.

Here we characterize three Sphingobium fuliginis strains—TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3—isolated from rhizosphere sediment of the reed Phragmites australis. These strains could use 4-tert-butylphenol as a sole carbon source. On the basis of additional tests of strain TIK-1, we propose that it degrades 4-tert-butylphenol through 4-tert-butylcatechol along a meta-cleavage pathway. We also show that strain TIK-1 cells grown on 4-tert-butylphenol can degrade a wide range of 4-alkylphenols via a meta-cleavage pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Alkylphenols {4-ethylphenol, 2-n-propylphenol, 2-isopropylphenol, 3-isopropylphenol, 4-n-propylphenol, 4-isopropylphenol, 2-sec-butylphenol, 2-tert-butylphenol, 3-tert-butylphenol, 4-n-butylphenol, 4-sec-butylphenol, 4-tert-butylphenol, 4-n-pentylphenol, 4-tert-pentylphenol, 4-n-hexylphenol, 4-n-heptylphenol, 4-n-octylphenol, 4-tert-octylphenol [4-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl) phenol], 4-n-nonylphenol, technical nonylphenol, and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol}, 4-tert-butylcatechol, 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol, methyl alkyl ketones (2-pentanone, 2-hexanone, 3-methyl-2-pentanone, 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone, 2-heptanone, 2-octanone, 2-nonanone, 2-decanone, and 2-undecanone), and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Catechol was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan).

Culture media.

We used basal salts medium (BSM; pH 7.2) containing 1.0 g (NH4)2SO4, 1.0 g K2HPO4, 0.2 g NaH2PO4, 0.2 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.05 g NaCl, 0.05 g CaCl2, 8.3 mg FeCl3·6H2O, 1.4 mg MnCl2·4H2O, 1.17 mg Na2MoO4·2H2O, and 1 mg ZnCl2 per liter of water. BSM containing 4-tert-butylphenol (4tBP-BSM) as the sole carbon source was used for cultures of 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading bacteria. Agar solid medium was prepared with 2.0% (wt/vol) agar.

Enrichment, isolation, and identification of 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading bacteria.

A sample of P. australis rhizosphere sediment was obtained from Inukai Pond at Osaka University, Suita, Osaka, Japan. The rhizosphere sediment sample was collected from a depth of about 20 cm, around the P. australis roots. Detailed physicochemical analysis revealed that the sediment sample had a pH of 6.9, a low organic carbon content (ignition loss, 2.2%), and undetectable levels (<0.001 mg kg−1) of alkylphenols (4-n-butylphenol, 4-tert-butylphenol, 4-tert-octylphenol, and 4-nonylphenol). For enrichment of 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading bacteria from the rhizosphere sediment, about 1 g (wet weight) of sediment sample was added to 100 ml 4tBP-BSM (0.5 mM 4-tert-butylphenol). The mixture was incubated at 28°C on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm for 14 days, and then 1 ml of this enrichment culture was transferred to 100 ml fresh 4tBP-BSM (0.5 mM) and incubated for 14 days. After a third transfer, the enriched culture was serially diluted and spread on 4tBP-BSM (0.5 mM) agar plates, and the plates were incubated at 28°C. The isolated bacterial strains, designated TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3, were characterized and identified by physiological and phylogenetic analyses as described previously. The strains were morphologically and physiologically characterized by using an API 20NE kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (bioMérieux Japan, Tokyo, Japan). A comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis was performed as follows. Partial 16S rRNA genes were amplified by PCR using primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1392R (5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTACA-3′) (3). The determination of the amplified 16S rRNA gene sequence was entrusted to Takara Bio (Shiga, Japan). The 16S rRNA gene sequences were compared to the reference sequence by using BLAST similarity searches (2), and closely related sequences were obtained from GenBank. The sequences were aligned by using CLUSTAL W (8). A phylogenetic tree was produced by njplotWIN95 software (31).

Growth and degradation experiments.

Each isolate was grown overnight in 4tBP-BSM (1.0 mM). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (9,600 × g at 4°C for 10 min), washed twice with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and inoculated to a cell density (as determined by the optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm [OD600]) of 0.02 (i.e., OD600 = 0.02) in 100 ml 4tBP-BSM (1.0 mM) or in 100 ml BSM containing 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol as the sole carbon source. Culture was carried out at 28°C and 120 rpm under dark conditions. The experiments for each of the two types of BSM were conducted in triplicate. Cell densities, substrate concentrations, and metabolic products were monitored over the 24-h experimental period (see below). We also performed 4-tert-butylphenol degradation experiments using cells of each isolate grown on glucose.

Inhibition experiments.

To check for the degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol via a meta-cleavage pathway, inhibition experiments were conducted with 3-fluorocatechol, which is a suicide inactivator of meta-cleaving catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (5, 18). Whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol, prepared as described above, were resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) with or without 0.2 mM 3-fluorocatechol, and then the suspension was incubated for 30 min before the start of the experiment. Then, 5 ml of one of the two types of cell suspension (i.e., whole-cell suspensions with or without 3-fluorocatechol treatment) was added to 5 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylphenol or 4-tert-butylcatechol. The reaction mixture (approximately 0.1 mg dry cells ml−1) was incubated at 25°C under dark conditions. The inhibition experiments were conducted in triplicate. Substrate concentrations were monitored over the 360-min experimental period (see below).

Enzyme assays.

Cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol, prepared as described above, were resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The cell suspension was kept on ice at all times and broken by ultrasonication (30 W, with four cycles of 30 s with a 30-s interval). Each sample was centrifuged (12,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min) and the supernatant was used as a crude cell extract for enzyme assays. Catechol 1,2-dioxygenase activity and catechol 2,3-dioxygenase activity were assayed by methods described by Nakazawa and Nakazawa (28) and Takeo et al. (37), respectively. The reaction was performed at 25°C in 1.5 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing the appropriate concentrations (10 to 1,000 μM) of catechol. In the catechol 1,2-dioxygenase assay, catechol 2,3-dioxygenase was inactivated by the addition of H2O2 (0.01%, vol/vol) for 5 min before the addition of catechol. In the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase assay, acetone was added (10%, vol/vol) to preparations for catechol 2,3-dioxygenase measurement. Protein was measured by the Lowry method, with bovine serum albumin as the standard. We defined one unit of enzyme activity (U) as the amount of enzyme that converted 1 μmol of substrate per minute.

Detection of 4-tert-butylcatechol cleavage products.

For detecting the 4-tert-butylcatechol cleavage products, we conducted a 4-tert-butylcatechol degradation test using whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol. Cells, prepared as described above, were resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol. Eighteen identical 10-ml whole-cell reaction mixtures (approximately 0.1 mg dry cells ml−1) were incubated in closed vials at 28°C. Three vials were sampled at the start of the experiment and three more each at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 60 min, and cells in the vials were broken by ultrasonication (30 W, with 4 cycles of 30 s at 30-s intervals). The samples were then subjected to analysis for metabolites (see below).

Utilization and degradation of other alkylphenols.

Alkylphenols with variously positioned, sized, and branched alkyl chains were used for growth experiments with strain TIK-1 and for degradation tests using strain TIK-1 whole cells grown on 4-tert-butylphenol. In the growth experiments, cells prepared as described above were added at an OD600 of 0.02 to 100 ml BSM supplemented with one of the following alkylphenols as the sole carbon source at 0.5 mM: 4-ethylphenol, 2-n-propylphenol, 2-isopropylphenol, 3-isopropylphenol, 4-n-propylphenol, 4-isopropylphenol, 2-sec-butylphenol, 2-tert-butylphenol, 3-tert-butylphenol, 4-n-butylphenol, 4-sec-butylphenol, 4-tert-butylphenol, 4-n-pentylphenol, 4-tert-pentylphenol, 4-n-hexylphenol, 4-n-heptylphenol, 4-n-octylphenol, 4-tert-octylphenol, 4-n-nonylphenol, technical nonylphenol, or 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol. Cultivation was carried out at 28°C and 120 rpm. The growth experiments were conducted in triplicate. Cell densities, substrate concentrations, and metabolic products were monitored over the 120-h experimental period (see below).

In the degradation tests, whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol were suspended in 10 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM one of the above-mentioned alkylphenols. The whole-cell reaction mixtures (approximately 0.1 mg dry cells ml−1) were incubated in closed vials at 28°C and 120 rpm. Three vials from each treatment were sampled at the start of the experiment and at 3, 24, 48, and 72 h. Concentrations of substrates and metabolic products were monitored (see below). As inhibition experiments, the degradation experiments were also performed in the presence of 0.2 mM 3-fluorocatechol.

Analytical procedures.

Bacterial growth was monitored by recording the increase in OD600. The dry weights of cells were also determined at the ends of the growth experiments. For dry weight measurement, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (9,600 × g at 4°C for 10 min), washed twice with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and then filtered through a preweighed filter (pore size, 0.2 μm; polycarbonate; Millipore, Tokyo, Japan). The filter, together with the cells, was dried at 90°C for 3 h and then weighed.

Alkylphenols and 4-tert-butylcatechol concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone concentration was determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and metabolites of 4-tert-butylphenol and other alkylphenols were analyzed by GC-MS. For the HPLC and GC-MS analyses, the culture sampled at each sampling point was acidified with 1 N HCl to pH 2 to 3, shaken for 3 min with an equal volume of 2:1 (vol/vol) ethyl acetate-n-hexane, and centrifuged (3,200 × g at 4°C for 10 min); the organic layer was then collected. For HPLC analysis, the extract (200 μl) was dried under flowing nitrogen, and the dry extract was dissolved in 200 μl acetonitrile before analysis. For GC-MS analysis, the extract (2 to 10 ml) was dried under nitrogen flow, and the dry extract was dissolved in 100 μl acetonitrile before analysis. In addition, the extract (2 to 10 ml) was dried under nitrogen flow and then subjected to trimethylsilylation (TMS) at 60°C for 1 h using 100 μl of BSTFA-acetonitrile solution (1:1, vol/vol). The sample with TMS derivatization was analyzed by GC-MS.

HPLC analysis was conducted in a Shimadzu HPLC system with a UV/visible-light (UV/vis) detector and a Shim-pack VP-ODS column (150 mm by 4.6 mm; particle size, 5 μm; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). In the HPLC analysis, acetonitrile-water (8:2, vol/vol) was used as the mobile phase and detection was at a wavelength of 277 nm. The GC-MS analysis was conducted with a Shimadzu GC-MS system (GCMS-QP2010) and an Rxi-5ms capillary column (30 m; 0.25-mm inside diameter [ID]; 1.00-μm film thickness [df]; Restek, Bellefonte, PA). For the GC-MS analysis, two column temperature programs were used. For the analysis of metabolites without TMS derivatization, the temperature was held at 60°C for 2 min, increased to 300°C at 5°C min−1, and then held at 300°C for 5 min. For the analysis of metabolites with TMS derivatization, the column temperature was held at 90°C for 1 min, increased to 150°C at a rate of 15°C min−1, increased to 300°C at 5°C min−1, and then held at 300°C for 6 min. The injection, interface, and ion source temperatures were 280°C, 280°C, and 250°C, respectively. Helium (99.995%) was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1. The degradation products were identified by their electron impact mass spectrometry (EIMS) spectral data. The National Institute of Standards and Technologies (NIST) MS fragment library (NIST08) was used for the identifications.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence data of strains TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3 have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers AB491315, AB491316, and AB491317, respectively.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading bacteria.

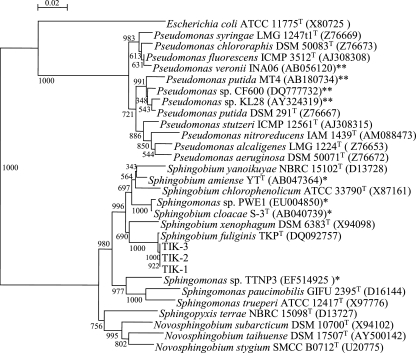

The P. australis rhizosphere sediment sample was incubated in 4tBP-BSM (0.5 mM) to check for 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading ability. The 4-tert-butylphenol completely disappeared from the rhizosphere sediment culture within 14 days. Enrichment culture of the rhizosphere sediment resulted in the isolation of three bacterial strains, designated TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3, that could be aerobically grown on 4-tert-butylphenol as a sole carbon and energy source. Strains TIK-1 and TIK-3 formed creamy yellow colonies on 4tBP-BSM (0.5 mM) agar plates, whereas strain TIK-2 formed bright yellow colonies on the same agar plates. The three isolates were rod-shaped, Gram-negative, and catalase- and oxidase-positive bacteria. They utilized glucose, l-arabinose, and maltose as sole carbon sources but not d-mannose,d-mannitol, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, gluconate, n-caprate, adipate, d,l-malate, citrate, or phenylacetate. The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences of the isolates corresponded to each other and showed the closest sequence identity (99.8%) to that of Sphingobium fuliginis TKPT. Therefore, we identified strains TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3 as S. fuliginis. We used the neighbor-joining method to establish the phylogenetic relationships of strains TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3 on the basis of their 16S rRNA gene sequences and also from their relationships to closely related type strains and previously isolated alkylphenol-degrading bacterial strains (Fig. 1). All three isolates were phylogenetically related to 4-nonylphenol-degrading and 4-tert-octylphenol-degrading bacteria and distant from medium-chain 4-n-alkylphenol-degrading bacteria.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships between strains TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3, type strains of Sphingomonadaceae and Pseudomonas sp., and previously isolated 4-nonylphenol-degrading and 4-octylphenol-degrading (*) and medium-chain 4-n-alkylphenol-degrading (**) bacterial strains, established by the neighbor-joining method on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequences. Numbers on branches indicate bootstrap confidence estimates obtained with 1,000 replicates. The scale bar represents an evolutionary distance (Knuc) of 0.02.

Degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol and 4-tert-butylcatechol by strain TIK-1.

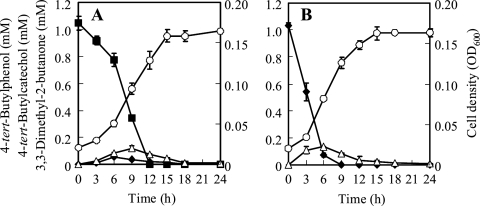

All three isolates were able to rapidly degrade 4-tert-butylphenol at almost the same rate, and we selected strain TIK-1 for further studies. Strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol completely degraded 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylphenol within 12 h, and the bacterial cell density (OD600) increased in parallel with 4-tert-butylphenol degradation (Fig. 2A). One metabolite peak was detected by HPLC analysis at a retention time (RT) of 2.3 min after 3 h of incubation, along with a decrease in 4-tert-butylphenol at an RT of 4.4 min. The metabolite peak was identified as that of 4-tert-butylcatechol, because the RT in HPLC and the MS spectrum of the isolated peak corresponded to those of authentic 4-tert-butylcatechol. The concentration of 4-tert-butylcatechol in the culture medium increased over the period from 3 to 6 h, when it reached a maximum of 0.06 mM, and it subsequently decreased to an undetectable level within 18 h (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, another notable metabolite peak was detected by GC-MS analysis without TMS derivatization after 3 h of incubation at an RT of 4.6 min. The RT and MS spectrum of this peak corresponded to those of authentic 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone, which retains the tert-butyl chain structure. The concentration of 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone in the culture medium increased over the period from 3 to 9 h, when it reached 0.12 mM, and it then gradually decreased to 0.009 mM within 24 h (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol and cell growth of S. fuliginis strain TIK-1 in basal salts medium (BSM) containing 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylphenol (A) and degradation of 4-tert-butylcatechol and cell growth of strain TIK-1 in BSM containing 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol (B). The concentrations of 4-tert-butylphenol (closed squares), 4-tert-butylcatechol (closed diamonds), and 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone (open triangles) and the cell densities (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]; open circles) were monitored over 24 h. Data points represent the means of results from triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol completely degraded 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol within 9 h, with concomitant cell growth (Fig. 2B). 3,3-Dimethyl-2-butanone was formed after 3 h of incubation, along with the decrease in 4-tert-butylcatechol. The concentration of 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone in the culture medium increased between 3 and 6 h to 0.13 mM and then gradually decreased to 0.008 mM within 24 h (Fig. 2B).

The dry weights of cells were determined after a 24-h incubation of strain TIK-1 with 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylphenol or 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol. The yield coefficients of the cells were 75.3 ± 6.99 mg (dry weight)/mmol 4-tert-butylphenol and 74.9 ± 1.85 mg (dry weight)/mmol 4-tert-butylcatechol.

These results indicated that 4-tert-butylphenol was initially transformed to 4-tert-butylcatechol by strain TIK-1, and then 4-tert-butylcatechol was further metabolized and served as the growth substrate.

In 4-tert-butylphenol degradation experiments using strain TIK-1 cells grown on glucose, degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol was observed after a lag period of 42 h, and 1.0 mM 4-tert-butylphenol disappeared within 60 h (data not shown). The results indicated that 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading activity was inducible in strain TIK-1.

Inhibition of 4-tert-butylphenol and 4-tert-butylcatechol degradation in strain TIK-1.

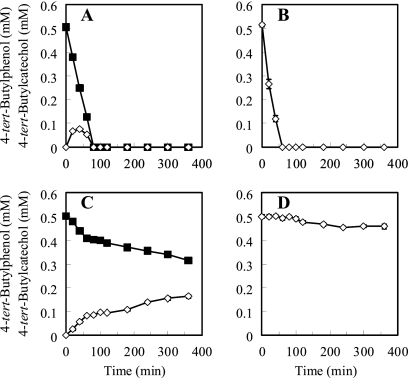

3-Fluorocatechol, a meta-cleavage inhibitor, substantially inhibited the degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol and 4-tert-butylcatechol by whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol (Fig. 3). Whole cells without 3-fluorocatechol treatment rapidly degraded 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylphenol within 80 min. 4-tert-Butylcatechol was formed and accumulated transiently during the first 60 min. When the 4-tert-butylphenol was depleted, the 4-tert-butylcatechol also disappeared (Fig. 3A). Whole cells without 3-fluorocatechol treatment also completely degraded 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol within 60 min (Fig. 3B). In contrast, whole cells with 3-fluorocatechol treatment degraded 4-tert-butylphenol slightly, and 1.86 μmol of 4-tert-butylphenol was removed within 360 min. Over the experimental period, 4-tert-butylcatechol was formed and accumulated, with the corresponding stoichiometric degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol. By the end of the 360-min experiment, 1.74 μmol of 4-tert-butylcatechol had been formed (Fig. 3C). Whole cells with 3-fluorocatechol treatment degraded 4-tert-butylcatechol slightly, and 0.41 μmol 4-tert-butylcatehol was removed (Fig. 3D). Hollender et al. (18) observed similar inhibition by a 3-halocatechol of 4-chlorophenol biodegradation via a meta-cleavage pathway and the accumulation of 4-chlorocatechol. Murdoch and Hay (27) demonstrated that isobutylcatechol can be metabolized by Sphingomonas sp. strain Ibu-2 via a meta-cleavage pathway and that this metabolism is inhibited by the addition of 3-fluorocatechol. Thus, these results suggest the involvement of a meta-cleavage pathway in 4-tert-butylphenol degradation by strain TIK-1.

FIG. 3.

Influence of 3-fluorocatechol on degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol and 4-tert-butylcatechol by whole cells of S. fuliginis strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol. Whole cells without 0.2 mM 3-fluorocatechol treatment were incubated in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylphenol (A) or 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol (B). In addition, whole cells subjected to 0.2 mM 3-fluorocatechol treatment for 30 min before the degradation tests were incubated in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylphenol (C) or 0.5 mM 4-tert-butylcatechol (D). Concentrations of 4-tert-butylphenol (closed squares) and 4-tert-butylcatechol (open diamonds) were monitored over 360 min. Data points represent the means results from of triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Identification of enzyme involved in degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol by strain TIK-1.

To investigate whether degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol proceeds via an ortho- or a meta-cleavage pathway, we tested for the presence of catechol 1,2-dioxygenase and catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. The specific activities of the enzymes in crude cell extract of S. fuliginis strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol were as follows: for catechol 1,2-dioxygenase, <1 mU mg−1 protein (below the limit of detection for the enzyme assays), and for catechol 2,3-dioxygenase, 16.9 mU mg−1 protein. We detected the activity of the meta-cleavage pathway enzyme catechol 2,3-dioxygenase in a cell extract of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol, whereas we did not detect catechol 1,2-dioxygenase activity. These results also support the conclusion that a meta-cleavage pathway is involved in 4-tert-butylphenol degradation by strain TIK-1.

Detection of 4-tert-butylcatechol meta-cleavage products.

To detect 4-tert-butylcatechol meta-cleavage products, we conducted a 4-tert-butylcatechol degradation test using whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol. Ethyl acetate-n-hexane extracts with TMS derivatization were analyzed by GC-MS. The peaks of four metabolites were detected by GC-MS analysis at RTs of 12.6, 18.0, 19.6, and 19.9 min after 10 min of incubation, along with a decrease in 4-tert-butylcatechol at an RT of 14.6 min. The EIMS spectral data and ion peak patterns of these metabolites are shown in Fig. S1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material. The relative abundances of the molecular ion (M)+ in these EIMS spectra were low. The ion peaks showing loss of CH3, loss of CH3 plus CO, and loss of C4H9O2Si had relatively high intensities. These EIMS spectral characteristics have been observed for different meta-cleavage products (24, 33, 40). Also, in the inhibition experiment with 3-fluorocatechol, these metabolite peaks were not detected. Therefore, these metabolites were tentatively identified as meta-cleavage products of 4-tert-butylcatechol. The meta-cleavage of 4-alkylcatechol yields two possible products, depending on the ring-cleavage styles, namely, proximal cleavage (2,3-cleavage) and distal cleavage (1,6-cleavage) (37). However, we did not identify the ring cleavage style of strain TIK-1 and meta-cleavage products, because we could not isolate an adequate amount of each metabolite and get authentic compounds.

Utilization and degradability of various alkylphenols.

The ability of strain TIK-1 to utilize and degrade a variety of alkylphenols is summarized in Table 1. Among the alkylphenols tested, 4-isopropylphenol, 4-sec-butylphenol, and 4-tert-pentylphenol were utilized by strain TIK-1 for growth, in addition to 4-tert-butylphenol. The rates of cell growth on 4-isopropylphenol (specific growth rate, 0.091 h−1), 4-sec-butylphenol (0.15 h−1), and 4-tert-pentylphenol (0.094 h−1) were substantially lower than those observed on 4-tert-butylphenol (0.22 h−1).

TABLE 1.

Utilization and degradability of various alkylphenols by S. fuliginis strain TIK-1

| Substrate | Growtha | Transformation ratio (%)b | Main degradation productc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Ethylphenol | − | 100 | ND |

| 2-n-Propylphenol | − | 0 | ND |

| 2-Isopropylphenol | − | 0 | ND |

| 3-Isopropylphenol | − | 0 | ND |

| 4-n-Propylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Pentanoned |

| 4-Isopropylphenol | + | 100 | 3-Methyl-2-butanonee |

| 2-sec-Butylphenol | − | 0 | ND |

| 2-tert-Butylphenol | − | 9.7 | ND |

| 3-tert-Butylphenol | − | 0 | ND |

| 4-n-Butylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Hexanoned |

| 4-sec-Butylphenol | + | 100 | 3-Methyl-2-pentanoned |

| 4-tert-Butylphenol | + | 100 | 3,3-Dimethyl-2-butanoned |

| 4-n-Pentylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Heptanoned |

| 4-tert-Pentylphenol | + | 100 | 3,3-Dimethyl-2-pentanonee |

| 4-n-Hexylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Octanoned |

| 4-n-Heptylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Nonanoned |

| 4-n-Octylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Decanoned |

| 4-tert-Octylphenol | − | 98.0 | 3,3,5,5-Tetramethyl-2-hexanonee |

| 4-n-Nonylphenol | − | 100 | 2-Undecanoned |

| Technical nonylphenol | − | 64.0 | Methyl branched nonyl ketonese |

| 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | − | 37.2 | 3,5-Di-tert-butylcatechold |

“+” indicates a substantial increase in cell density (OD600) from the initial 0.02 to >0.05; “−” indicates no substantial increase in cell density.

Transformation ratios (TR) were calculated from HPLC chromatograms obtained from 72-h cultures of strain TIK-1 whole cells and autoclaved sterile controls as follows: TR (%) = [1 − (substrate peak area from whole-cell culture)/(substrate peak area from sterile control)] × 100.

The main degradation products were detected by GC-MS analysis. ND, not detected.

Compound identified by comparison of EIMS spectral data with those of commercial authentic compounds.

Compound identified by analysis of its EIMS spectral data.

Whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol degraded the following alkylphenols: 4-ethylphenol, 4-n-propylphenol, 4-isopropylphenol, 2-tert-butylphenol, 4-n-butylphenol, 4-sec-butylphenol, 4-tert-butylphenol, 4-n-pentylphenol, 4-tert-pentylphenol, 4-n-hexylphenol, 4-n-heptylphenol, 4-n-octylphenol, 4-tert-octylphenol, 4-n-nonylphenol, technical nonylphenol, and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol. Methyl alkyl ketones (except in the cases of 4-ethylphenol, 2-tert-butylphenol, and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol) were detected as the main degradation products at 3 h of incubation (Table 1). The GC-MS RTs and EIMS spectra of 2-pentanone, 2-hexanone, 3-methyl-2-pentanone, 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone, 2-heptanone, 2-octanone, 2-nonanone, 2-decanone, and 2-undecanone corresponded to those of authentic compounds (see Fig. S2 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). Other methyl alkyl ketones detected were tentatively identified by analysis of their EIMS spectral data (see Fig. S2 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). These methyl alkyl ketones were probably derived from the alkyl side chains of alkylphenols, because they had the same structures as the original alkyl side chains. 3,3,5,5-Tetramethyl-2-hexanone formed by 4-tert-octylphenol degradation and methyl branched nonyl ketones formed by technical nonylphenol degradation persisted in each closed vial after the end of the experiments. However, the concentrations of the other methyl alkyl ketones in the closed vials decreased to undetectable levels within 24 h. In the 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol degradation test, 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol was accumulated as the dead-end degradation product. The RT and EIMS spectrum of this GC-MS peak corresponded to those of authentic 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol (see Fig. S2 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). The amount of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol lost (0.186 mM) was approximately stoichiometrically equal to the amount of 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol (0.178 mM) formed by the end of the experiment, indicating that the former was transformed to the latter. In the inhibition experiments in the presence of 3-fluorocatechol, there was no substantial degradation of the alkylphenols or production of the corresponding methyl alkyl ketones.

2-n-Propylphenol, 2-isopropylphenol, 3-isopropylphenol, 2-sec-butylphenol, and 3-tert-butylphenol were neither utilized for growth nor degraded by strain TIK-1.

DISCUSSION

Three aerobic bacterial strains (Sphingobium fuliginis strains TIK-1, TIK-2, and TIK-3) capable of utilizing 4-tert-butylphenol as the sole carbon and energy source were isolated from P. australis rhizosphere sediment in a pond. All three strains were phylogenetically related to branched 4-nonylphenol-degrading sphingomonad strains rather than to 4-n-butylphenol-degrading Pseudomonas strains (Fig. 1).

Previous studies of the biodegradation of alkylphenols have clearly demonstrated that branched 4-nonylphenol and 4-tert-octylphenol, which have long alkyl side chains with α-quaternary carbons, can be degraded by sphingomonad strains TTNP3 (6, 7), Bayram (11-14), and PWE1 (32) by an ipso-substitution mechanism; in contrast, 4-n-butylphenol, which has a shorter alkyl side chain with an α-secondary carbon, can be degraded by Pseudomonas strains KL28 (21) and MT4 (36) via a meta-cleavage pathway. Strains KL 28 and MT4 cannot degrade 4-tert-butylphenol. Resting cells of strain Bayram grown on technical nonylphenol show ipso-hydroxylating activity for 4-tert-butylphenol, but this strain cannot utilize 4-tert-butylphenol as a sole carbon source (11, 14). Until now, nothing has been known about the bacteria capable of utilizing 4-tert-butylphenol, which has a shorter alkyl side chain with an α-quaternary carbon, or the mechanisms of this biodegradation. Strain TIK-1 is thus, to our knowledge, the first 4-tert-butylphenol-utilizing bacterium to be identified.

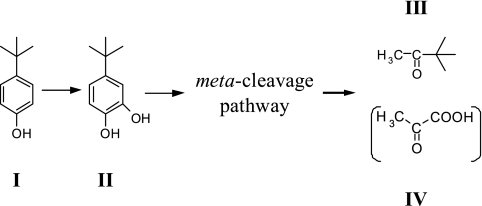

Our results here show that strain TIK-1 metabolizes 4-tert-butylphenol via a meta-cleavage pathway (Fig. 4). That is, 4-tert-butylphenol is initially hydroxylated to 4-tert-butylcatechol; 4-tert-butylcatechol is then further metabolized along a meta-cleavage pathway, eventually forming 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone with retention of the structure of the original tert-butyl side chain (Fig. 4). 3,3-Dimethyl-2-butanone was not the dead-end degradation product, because this compound was degraded in closed vials by whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol. In addition, we suspect that pyruvic acid is formed through a meta-cleavage pathway, although it was not detected in our analysis. Pyruvic acid (1.0 mM) supported cell growth of strain TIK-1 (data not shown). The proposed degradation pathway of 4-tert-butylphenol by strain TIK-1 resembles that of 4-n-butylphenol degradation by strains KL28 and MT4. n-Hexanal, an alkyl aldehyde with the original n-butyl side chain, is formed in 4-n-butylphenol degradation via the distal meta-cleavage pathway by strains KL28 (21) and MT4 (36). Interestingly, however, we did not detect alkyl aldehyde with the original 4-tert-butyl side chain in the degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol by strain TIK-1, nor did we detect n-hexanal in the degradation of 4-n-butylphenol. 3,3-Dimethyl-2-butanone and 2-hexanone, which are methyl alkyl ketones with the original butyl side chains, were formed in the metabolism of 4-tert- and 4-n-butylphenol, respectively, by strain TIK-1. Therefore, the pathway of degradation of 4-tert-butylphenol by strain TIK-1 almost certainly is not completely the same as that of 4-n-butylphenol by strains KL28 and MT4. There may be a difference in meta-cleavage styles, namely, proximal cleavage (2,3-cleavage) and distal cleavage (1,6-cleavage), between strain TIK and strains KL28 and MT4. Our group is undertaking further study to gain a more detailed understanding of the 4-tert-butylphenol-degrading enzymes in strain TIK-1.

FIG. 4.

Proposed pathway for the metabolism of 4-tert-butylphenol by S. fuliginis strain TIK-1. (I) 4-tert-butylphenol; (II) 4-tert-butylcatechol; (III) 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone; (IV) pyruvic acid.

Strain TIK-1 also utilized several 4-alkylphenols but did not utilize 2- and 3-alkylphenols. An important factor determining whether 4-alkylphenol is utilized by strain TIK-1 seems to be the presence of an α-quaternary or α-tertiary carbon, as shown by the finding that strain TIK-1 utilized 4-tert-butylphenol, with an α-quaternary carbon, and 4-sec-butylphenol, with an α-tertiary carbon, as the sole carbon source but did not utilize 4-n-butylphenol, with an α-secondary carbon. Also, strain TIK-1 utilized 4-tert-butylphenol at a much higher rate than for 4-sec-butylphenol. Alkylphenols with branched alkyl side chains, especially those with an α-quaternary carbon structure, are known to inhibit biological attack and biotransformation of the alkyl group (7, 41), and they are much more estrogenic than those with an α-tertiary or α-secondary carbon (34). Therefore, the growth-substrate specificity of strain TIK-1 is a notable feature and is very different from that of previously reported 4-n-butylphenol-degrading Pseudomonas strains. In addition, among the alkylphenols tested in this study, the growth substrate range of strain TIK-1 was limited to 4-alkylphenols with alkyl side chains of three to five carbon atoms (4-isopropylphenol, 4-sec-butylphenol, 4-tert-butylphenol, and 4-tert-pentylphenol). This indicates that the size of the alkyl side chain is also crucial for the utilization of 4-alkylphenol by strain TIK-1.

In contrast to their growth-substrate specificity, strain TIK-1 cells grown on 4-tert-butylphenol showed degradative activity for a surprisingly wide range of 4-alkylphenols with variously sized and branched alkyl side chains (ethyl, n-propyl, isopropyl, n-butyl, sec-butyl, tert-butyl, n-pentyl, tert-pentyl, n-hexyl, n-heptyl, n-octyl, tert-octyl, n-nonyl, and branched nonyl) (Table 1). Although technical nonylphenol is a complex mixture of more than 100 nonylphenol isomers (19), a substantial amount (64%) of 0.5 mM technical nonylphenol was degraded by whole cells of strain TIK-1 (Table 1). Thus, strain TIK-1 probably has degrading activity for various 4-nonylphenol isomers in technical nonylphenol. Our results indicate that such alkylphenols are degraded by whole cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol via a meta-cleavage pathway and that methyl alkyl ketones retaining the structure of the original alkyl side chains are formed by the aromatic ring cleavage. Furthermore, cells of strain TIK-1 grown on 4-tert-butylphenol transformed a dialkylphenolic compound (namely, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol) to 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol, but evidence for the aromatic ring cleavage of this compound was not observed.

The aerobic biodegradation of many aromatic compounds occurs via catechols as key metabolites. The breakdown of catechols in general proceeds via an ortho- or meta-cleavage pathway. Previous studies have demonstrated that a meta-cleavage pathway is involved in the degradation of short- and medium-chain 4-n-alkylphenols (4-methylphenol, 4-ethylphenol, 4-n-propylphenol, 4-n-butylphenol, 4-n-pentylphenol, 4-n-hexylphenol, and 4-n-heptylphenol) (21, 36, 37) and 2-alkylphenols (2-n-propylphenol, 2-isopropylphenol, and 2-sec-butylphenol) (24, 33, 40). To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that a single bacterial strain can degrade 4-alkylphenols with variously sized and branched side chains of two to nine carbon atoms, including 4-tert-octylphenol and technical nonylphenol, via a meta-cleavage pathway. Strain TIK-1 probably has meta-cleavage pathway enzymes with an unprecedentedly wide substrate specificity.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence that S. fuliginis strain TIK-1 utilizes 4-tert-butylphenol via a meta-cleavage pathway. Another noteworthy finding is that the substrate range of degradative activity in strain TIK-1 includes a wide range of 4-alkylphenols. Strain TIK-1 is potentially useful for removal of 4-tert-butylphenol and other 4-alkylphenols from polluted environments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported partly by grants-in-aid for (i) Encouragement of Young Scientists A (no. 21681010) and (ii) Young Scientists B (no. 19710060) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajithkumar, B., V. P. Ajithkumar, and R. Iriye. 2003. Degradation of 4-amylphenol and 4-hexylphenol by a new activated sludge isolate of Pseudomonas veronii and proposal for a new subspecies status. Res. Microbiol. 154:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barse, A. V., T. Chakrabarti, T. K. Ghosh, A. K. Pal, and S. B. Jadhao. 2006. One-tenth dose of LC50 of 4-tert-butylphenol causes endocrine disruption and metabolic change in Cyprinus carpio. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 86:172-179. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartels, I., H.-J. Knackmuss, and W. Reineke. 1984. Suicide inactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida mt-2 by 3-halocatechols. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:500-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corvini, P. F. X., J. Hollender, R. Ji, S. Schumacher, J. Prell, G. Hommes, U. Priefer, R. Vinken, and A. Schäffer. 2006. The degradation of α-quaternary nonylphenol isomers by Sphingomonas sp. strain TTNP3 involves a type II ipso-substitution mechanism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 70:114-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corvini, P. F. X., A. Schäffer, and D. Schlosser. 2006. Microbial degradation of nonylphenol and other alkylphenols—our evolving view. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72:223-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eddy, S. R. 1995. Multiple alignment using hidden Markov models, p. 114-120. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference of Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. The International Society for Computational Biology, La Jolla, CA. [PubMed]

- 9.European Chemicals Bureau. 2008. European Union risk assessment report, p-tert-butylphenol risk assessment. Final approved version. Norwegian Pollution Control Authority, Oslo, Norway.

- 10.Fujii, K., N. Urano, H. Ushio, M. Satomi, and S. Kimura. 2001. Sphingomonas cloacae sp. nov., a nonylphenol-degrading bacterium isolated from wastewater of a sewage-treatment plant in Tokyo. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabriel, F. L. P., W. Giger, K. Guenther, and H.-P. E. Kohler. 2005. Differential degradation of nonylphenol isomers by Sphingomonas xenophaga Bayram. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1123-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabriel, F. L. P., A. Heidlberger, D. Rentsch, W. Giger, K. Guenther, and H.-P. E. Kohler. 2005. A novel metabolic pathway for degradation of 4-nonylphenol environmental contaminants by Sphingomonas xenophaga Bayram. J. Biol. Chem. 280:15526-15533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel, F. L. P., M. Cyris, W. Giger, K. Guenther, and H.-P. E. Kohler. 2007. ipso-Substitution: a general biochemical and biodegradation mechanism to cleave α-quaternary alkylphenols and bisphenol A. Chem. Biodivers. 4:2123-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabriel, F. L. P., M. Cyris, N. Jonkers, W. Giger, K. Guenther, and H.-P. E. Kohler. 2007. Elucidation of the ipso-substitution mechanism for side-chain cleavage of α-quaternary 4-nonylphenols and 4-t-butoxyphenol in Sphingobium xenophagum Bayram. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3320-3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haavisto, T. E., N. A. Adamsson, S. A. Myllymäki, J. Toppari, and J. Paranko. 2003. Effects of 4-tert-octylphenol, 4-tert-butylphenol, and diethylstilbestrol on prenatal testosterone surge in the rat. Reprod. Toxicol. 17:593-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasselberg, L., S. Meier, and A. Svardal. 2004. Effects of alkylphenols on redox status in first spawning Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Aquat. Toxicol. 69:95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heemken, O. P., H. Reincke, B. Stachel, and N. Theobald. 2001. The occurrence of xenoestrogens in the Elbe River and the North Sea. Chemosphere 45:245-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollender, J., J. Hopp, and W. Dott. 1997. Degradation of 4-chlorophenol via the meta cleavage pathway by Comamonas testosteroni JH5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4567-4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ieda, T., Y. Horii, G. Petrick, N. Yamashita, N. Ochiai, and K. Kannan. 2005. Analysis of nonylphenol isomers in a technical mixture and in water by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39:7202-7207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue, K., Y. Yoshie, S. Kondo, Y. Yoshimura, and H. Nakazawa. 2002. Determination of phenolic xenoestrogens in water by liquid chromatography with coulometric-array detection. J. Chromatogr. A 946:291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong, J. J., J. H. Kim, C.-K. Kim, I. Hwang, and K. Lee. 2003. 3- and 4-alkylphenol degradation pathway in Pseudomonas sp. strain KL28: genetic organization of lap gene cluster and substrate specificities of phenol hydroxylase and catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. Microbiology 149:3265-3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko, E.-J., K.-W. Kim, S.-Y. Kang, S.-D. Kim, S.-B. Bang, S.-Y. Hamm, and D.-W. Kim. 2007. Monitoring of environmental phenolic endocrine disrupting compounds in treatment effluents and river waters, Korea. Talanta 73:674-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koh, C.-H., J. S. Khim, D. L. Villeneuve, K. Kannan, and J. P. Giesy. 2006. Characterization of trace organic contaminants in marine sediment from Yeongil Bay, Korea: 1. Instrumental analyses. Environ. Pollut. 142:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler, H.-P. E., M. J. E. C. van der Maarel, and D. Kohler-Staub. 1993. Selection of Pseudomonas sp. strain HBP1 Prp for metabolism of 2-propylphenol and elucidation of the degradative pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:860-866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manga, P., D. Sheyn, F. Yang, R. Sarangarajan, and R. E. Boissy. 2006. A role of tyrosinase-related protein 1 in 4-tert-butylphenol-induced toxicity in melanocytes: implications for vitiligo. Am. J. Pathol. 169:1652-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meier, S., T. E. Andersen, B. Norberg, A. Thorsen, G. L. Taranger, O. S. Kjesbu, R. Dale, H. C. Morton, J. Klungsøyr, and A. Svardal. 2007. Effects of alkylphenols on the reproductive system of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Aquat. Toxicol. 81:207-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murdoch, R. W., and A. G. Hay. 2005. Formation of catechols via removal of acid side chains from ibuprofen and related aromatic acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6121-6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakazawa, T., and A. Nakazawa. 1970. Pyrocatechase (Pseudomonas). Methods Enzymol. 17:518-522. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada, H., T. Tokunaga, X. Liu, S. Takayanagi, A. Matsushima, and Y. Shimohigashi. 2008. Direct evidence revealing structural elements essential for the high binding ability of bisphenol A to human estrogen-related receptor-γ. Environ. Health Perspect. 116:32-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsem, C. M., E. T. M. Meussen-Elholm, J. A. Holme, and J. K. Hongslo. 2002. Brominated phenols: characterization of estrogen-like activity in the human breast cancer cell-line MCF-7. Toxicol. Lett. 129:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrière, G., and M. Gouy. 1996. WWW-Query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie 78:364-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter, A. W., and A. G. Hay. 2007. Identification of opdA, a gene involved in biodegradation of the endocrine disrupter octylphenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7373-7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichlin, F., and H.-P. E. Kohler. 1994. Pseudomonas sp. strain HBP1 Prp degrades 2-isopropylphenol (ortho-cumenol) via meta cleavage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4587-4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Routledge, E. J., and J. P. Sumpter. 1997. Structural features of alkylphenolic chemicals associated with estrogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3280-3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun, H., X.-L. Xu, J.-H. Qu, X. Hong, Y.-B. Wang, L.-C. Xu, and X.-R. Wang. 2007. 4-Alkylphenols and related chemicals show similar effect on the function of human and rat estrogen receptor α in reporter gene assay. Chemosphere 71:582-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeo, M., S. K. Prabu, C. Kitamura, M. Hirai, H. Takahashi, D. Kato, and S. Negoro. 2006. Characterization of alkylphenol degradation gene cluster in Pseudomonas putida MT4 and evidence of oxidation of alkylphenols and alkylcatechols with medium-length alkyl chain. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 102:352-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeo, M., M. Nishimura, H. Takahashi, C. Kitamura, D. Kato, and S. Negoro. 2007. Purification and characterization of alkylphenol 2,3-dioxygenase from butylphenol degradation pathway of Pseudomonas putida MT4. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104:309-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanghe, T., W. Dhooge, and W. Verstraete. 1999. Isolation of a bacterial strain able to degrade branched nonylphenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:746-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tollefsen, K.-E., S. Eikvar, E. F. Finne, O. Fogelberg, and I. K. Gregersen. 2008. Estrogenicity of alkylphenols and alkylated non-phenolics in a rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) primary hepatocyte culture. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 71:370-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Maarel, M. J. E. C., and H.-P. E. Kohler. 1993. Degradation of 2-sec-butylphenol: 3-sec-butylcatechol, 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-7-methylnona-2,4-dienoic acid, and 2-methylbutyric acid as intermediates. Biodegradation 4:81-89. [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Ginkel, C. G. 1996. Complete degradation of xenobiotic surfactants by consortia of aerobic microorganisms. Biodegradation 7:151-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang, F., Z. Abdel-Malek, and R. E. Boissy. 1999. Effects of commonly used mitogens on the cytotoxicity of 4-tertiary butylphenol to human melanocytes. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 35:566-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang, F., R. Sarangarajan, I. C. L. Poole, E. E. Medrano, and R. E. Boissy. 2000. The cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by 4-tertiary butylphenol in human melanocytes are independent of tyrosinase activity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 114:157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.