Abstract

A suicide plasmid, pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec, employing recA from Escherichia coli and tetM as a selection marker, was used to generate ctpA knockout mutants in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri through targeted gene disruption. Inclusion of E. coli recA greatly enhanced both the consistency and the recovery of mutants generated by homologous recombination.

Mycoplasmas have the smallest genomes of free-living organisms (15, 23, 32), yet the range of infections that they cause and their host species are among the most diverse in the microbial world (15). A major limitation in unraveling the virulence factors of these microbes is the paucity of tools for genetic manipulation (18, 30). Transposon-based mutagenesis (3, 4, 11, 12, 16-19, 34, 35), which has been employed to define the minimally essential genes for sustaining life and also to generate mutants of interest (17, 19), is the most widely used approach to genetic manipulation of Mollicutes. Replicating plasmids based on oriC (2-5, 9, 10, 18, 20, 24) have been used with limited success for heterologous gene expression as well as for targeted gene disruption by single-crossover recombination for a number of mycoplasma species (2-4, 9, 10, 20, 24, 27). However, many passages are required before they are integrated into the chromosome (5, 27), and mutants may not be stable.

Although classical double-crossover homologous recombination using a suicide plasmid is potentially a powerful technique, recombination by double-crossover has been reported only for Mycoplasma genitalium, and even then it occurs at a very low frequency (1, 7, 8). We report here the development of a suicide plasmid for targeted homologous recombination in M. mycoides subsp. capri that incorporates recA from Escherichia coli and tetM as a selection marker and that results in consistent recovery of targeted stable double-crossover mutants. As a target gene for disruption, we chose the M. mycoides subsp. capri ctpA gene (MMCAP2_0241), which confers a proteolytic phenotype that can readily be determined by growth on casein agar. Complete experimental details and results are provided in the supplemental material.

M. mycoides subsp. capri GM12-type ATCC 35297 (6), formerly known as the M. mycoides subsp. mycoides large-colony type (28), and Mycoplasma capricolum ATCC 27343 (26) were grown at 37°C in SP4 medium (33); SP4 casein agar was supplemented with a final concentration of 1% skim milk (Difco, Detroit, MI). For growth of mutants, 5 μg/ml tetracycline was added to the media. PCRs (Applied Biosystems Perkin Elmer GeneAmp 2400 PCR system) used either 1 μg of genomic DNA or 100 ng of plasmid DNA as a template for the PCRs and 30 pmol of the primer (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Primer pairs used for PCR

| Primer pair | Target (direction) | 5′→3′ sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ctpA coding sequence (forward) | CACCATGAAACTAGTTAAAAAAATAG |

| ctpA coding sequence (reverse) | CTTACTAAGGTTAATTTTTGTTATTTTAA | |

| 2 | ctpA USE (forward) | GGATCCCATTTTTATACAAATGTTTTTTTCTTTGG |

| ctpA coding sequence (reverse) | CTTACTAAGGTTAATTTTTGTTATTTTAA | |

| 3 | E. coli recA (forward) | ACTAGTTATGGCTATCGACGAAAACAAACAG |

| E. coli recA (reverse) | CTCTAGAGATGCGACCCTTGTGTATCAAAC | |

| 4 | ctpA flanking sequence (thiI) (forward) | GGATCCGTTTATAAAAATGGAGAATTTGCACAA |

| ctpA flanking sequence (reverse) | CTATTCACTATAGTATTAGGAAAAAAA | |

| 5 | tetM BB14 | CGTATATATGCAAGACG |

| tetM BB15 | TTATCAACGGTTTATCAGG | |

| 6 | Tn4001t sequence | GTACTCAATGAATTAGGTGGAAGACCGAGG |

Restriction enzyme sites that were created for cloning purposes are underlined. GGATCC is an introduced BamHI site, ACTAGT is an introduced SpeI site, and TCTAGA is an introduced XbaI site.

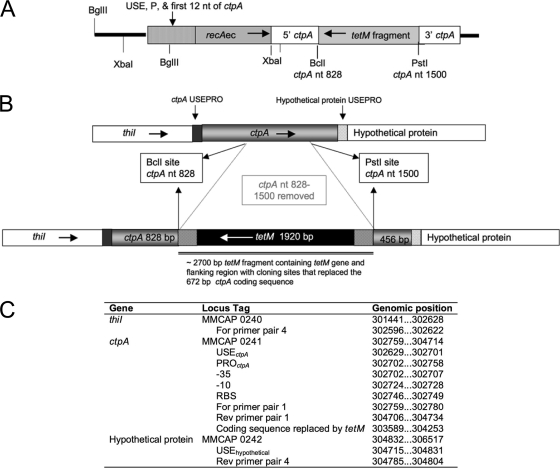

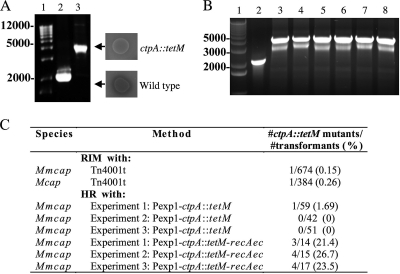

A tetM-containing fragment cloned from pIVT-1 (22) and flanked by the 5′ and 3′ ends of the ctpA coding sequence was cloned into pExp1-ctpA to produce pExp1-ctpA::tetM. The flanking regions were chosen to provide sufficient homologous sequences to facilitate recombination in the target gene (7-9). The insertion and the direction were verified by digestion with KpnI. pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec included the E. coli recA gene inserted in frame behind the first four codons of ctpA and under the direction of the upstream sequences (USE) and promoter region of ctpA (Fig. 1 A and C). Insertion and direction were confirmed for each step by restriction digestion. For random insertional mutagenesis, M. mycoides subsp. capri was transformed with Tn4001t by polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000)-mediated chemical transformation (11, 25). For targeted mutagenesis, M. mycoides subsp. capri GM12 was transformed with either pExp1-ctpA::tetM or pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec using PEG 8000-mediated chemical transformation. Mycoplasma capricolum was transformed by electroporation. Disruption of ctpA was confirmed by loss of its proteolytic phenotype and PCR (Fig. 2 A and B). The location, precise site of insertion, and direction of insertion of tetM into the coding sequence of ctpA were determined by sequencing.

FIG. 1.

Disruption of ctpA in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri by homologous recombination using pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec. (A) Diagrammatic information on preparation of pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec; (B) diagrammatic representation of genomic DNA of the Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri wild type and M. mycoides subsp. capri ctpA::tetM mutant obtained by homologous recombination; (C) relevant genomic locations (GenBank CP001621) of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri strain GM12 (the complete genome is available at http://cbi.labri.fr/outils/molligen/). P, promoter; USEPRO, USE and promoter; PROctpA, ctpA promoter; For, forward; Rev, reverse; RBS, ribosome binding site.

FIG. 2.

Disruption of the ctpA gene through homologous recombination results in loss of the proteolytic phenotype and is enhanced by inclusion of E. coli recA. (A) PCR amplification of genomic DNA using primer pair 4 and the corresponding phenotype from the M. mycoides subsp. capri wild type and M. mycoides subsp. capri ctpA::tetM mutant obtained by homologous recombination using pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec. (B) PCR amplification of genomic DNA using primer pair 4 from the M. mycoides subsp. capri wild type and six ctpA::tetM mutants obtained through homologous recombination using pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec. Numbers at the left of the blots are molecular weights. (C) Consistent recovery of mutants with disruption in ctpA was enhanced by inclusion of exogenous recA. #, number of; RIM, random insertional mutagenesis; HR, homologous recombination; Mcap, Mycoplasma capricolum; Mmcap, M. capricolum.

ctpA disruption was confirmed by Southern and Northern blotting. Genomic DNA samples were prepared (DNeasy tissue kit; Qiagen), and Southern blots were hybridized with labeled (DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit I; Roche) tetM and plasmid backbone probes. Total RNA was prepared using RiboPure bacteria from early-stationary-phase M. mycoides subsp. capri or M. mycoides subsp. capri ctpA::tetM cultures, and Northern blotting was performed using NorthernMax kit (Ambion) protocols. Based on Northern blotting, ctpA appears to be monocistronic, as the length of the transcript in M. mycoides subsp. capri was the same size as the mature open reading frame (ORF). Additionally, in Mycoplasma capricolum, disruption of either the upstream gene (MCAP_0239, Tn4001t insertion site at nucleotide [nt] 288746) or the downstream gene (MCAP_0241, Tn4001t insertion site at nt 292860) had no impact on the proteolytic phenotype, whereas disruption of ctpA (MCAP_0240, Tn4001t insertion at nt 291291) resulted in the inability to hydrolyze casein agar.

Targeted or random mutagenesis of M. mycoides subsp. capri ctpA as well as random insertional mutagenesis of Mycoplasma capricolum ctpA (MCAP_0240) resulted in loss of the proteolytic phenotype (Fig. 2A; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). All experiments with M. mycoides subsp. capri used 108 CFU of the wild type, 30 μg of plasmid DNA, and PEG 8000-mediated chemical transformation. Thus, the experimental conditions were identical, with the exception of the plasmid construct used. Transformation with pExp1-ctpA::tetM resulted in one mutant being obtained by a single-crossover event (Fig. 2C). Importantly, transformation with pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec resulted in multiple mutants obtained by a double-crossover event that was confirmed by DNA sequencing and PCR. Targeted mutation through homologous recombination resulted in replacement of 672 bp of the ctpA coding sequence with a 2,700-bp tetM-containing fragment (Fig. 1B and 2A and B). The presence and copy number of the tetM gene in all mutants were confirmed by Southern blotting. The absence of transcription of ctpA in the mutants was confirmed by Northern blotting.

Inclusion of recA from E. coli greatly enhanced the recovery of ctpA mutants (Fig. 2C). With Tn4001t (13) random insertional mutagenesis, the probability of obtaining the desired mutant was 1/674 (0.15%) for M. mycoides subsp. capri and 1/384 (0.26%) for Mycoplasma capricolum. In three independent experiments using pExp1-ctpA::tetM to create a targeted mutation, only 1 of 152 (0.66%) tetracycline-resistant clones screened from a single experiment was identified as a ctpA::tetM mutant. However, when recA was added to the construct, a dramatic and consistent increase in the likelihood of obtaining a ctpA::tetM mutant was observed. In three independent transformation experiments, a disruption in the targeted gene was obtained in 3/14 (21.4%), 4/17 (23.5%), and 4/15 (26.7%) transformants (Fig. 2C). Importantly, obtaining the desired mutants at approximately the same frequency in each independent experiment demonstrated the high level of consistency with the pExp-ctpA::tetM-recAec construct.

In mycoplasmas, recA is the only recombination gene universally present, but recA is not part of the essential gene set (16, 17). Recombination events in Mollicutes are likely RecA dependent (14, 29, 31). Thus, we reasoned we might be able to augment homologous recombination by inclusion of a heterologous source of RecA with a high GC content to minimize recombination with the indigenous recA. In our study, inclusion of the E. coli recA resulted in a 140-fold increase in the percentage of transformants that had the desired mutation. Importantly, all ctpA::tetM mutants that were obtained using pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec occurred by double-crossover homologous recombination and are therefore far more likely to be stable. Unlike the mutant obtained by random insertional mutagenesis using Tn4001t, the mutants obtained with pExp1-ctpA::tetM-recAec did not contain remnants of the plasmid backbone, which may also enhance stability. To the best of our knowledge, a successful classical double-crossover homologous recombination using a suicide plasmid in a mycoplasma has been reported previously only for M. genitalium (1, 21). This simple yet elegant approach provides a significant advance in our ability to manipulate the M. mycoides subsp. capri genome. Like with oriC, this technique may have applicability in other mycoplasmal species. This technique provides a new and promising approach that provides an additional genetic tool to use in unraveling the pathogenic mechanisms by which these microbes induce disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Dybvig for providing pIVT-1 and Tn4001t and A. Blanchard and J. Renaudin for providing pMP05.

The majority of our work was funded by USDA CSREES grant 99-35204-8367 to M.B.B. and subcontract 6415-100607 to M.B.B. from the University of South Florida Center for Biological Defense (contract W911SR-06-C-0023). L.R. was supported by Public Health Service grant 5K08DK07651 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. N.A.-G. and J.I.G. were supported by the Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy (cooperative agreement no. DE-FC02-02ER63453).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burgos, R., O. Q. Pich, E. Querol, and J. Pinol. 2008. Deletion of the Mycoplasma genitalium MG_217 gene modifies cell gliding behaviour by altering terminal organelle curvature. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1029-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chopra-Dewasthaly, R., C. Citti, M. D. Glew, M. Zimmermann, R. Rosengarten, and W. Jechlinger. 2008. Phase-locked mutants of Mycoplasma agalactiae: defining the molecular switch of high-frequency Vpma antigenic variation. Mol. Microbiol. 67:1196-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra-Dewasthaly, R., M. Marenda, R. Rosengarten, W. Jechlinger, and C. Citti. 2005. Construction of the first shuttle vectors for gene cloning and homologous recombination in Mycoplasma agalactiae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:89-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra-Dewasthaly, R., M. Zimmermann, R. Rosengarten, and C. Citti. 2005. First steps towards the genetic manipulation of Mycoplasma agalactiae and Mycoplasma bovis using the transposon Tn4001mod. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294:447-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordova, C. M., C. Lartigue, P. Sirand-Pugnet, J. Renaudin, R. A. Cunha, and A. Blanchard. 2002. Identification of the origin of replication of the Mycoplasma pulmonis chromosome and its use in oriC replicative plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 184:5426-5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DaMassa, A. J., D. L. Brooks, and H. E. Adler. 1983. Caprine mycoplasmosis: widespread infection in goats with Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides (large-colony type). Am. J. Vet. Res. 44:322-325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhandayuthapani, S., M. W. Blaylock, C. M. Bebear, W. G. Rasmussen, and J. B. Baseman. 2001. Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) is a virulence determinant in Mycoplasma genitalium. J. Bacteriol. 183:5645-5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhandayuthapani, S., W. G. Rasmussen, and J. B. Baseman. 1999. Disruption of gene mg218 of Mycoplasma genitalium through homologous recombination leads to an adherence-deficient phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:5227-5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duret, S., A. Andre, and J. Renaudin. 2005. Specific gene targeting in Spiroplasma citri: improved vectors and production of unmarked mutations using site-specific recombination. Microbiology 151:2793-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duret, S., N. Berho, J. L. Danet, M. Garnier, and J. Renaudin. 2003. Spiralin is not essential for helicity, motility, or pathogenicity but is required for efficient transmission of Spiroplasma citri by its leafhopper vector Circulifer haematoceps. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6225-6234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dybvig, K., and J. Alderete. 1988. Transformation of Mycoplasma pulmonis and Mycoplasma hyorhinis: transposition of Tn916 and formation of cointegrate structures. Plasmid 20:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dybvig, K., and G. H. Cassell. 1987. Transposition of gram-positive transposon Tn916 in Acholeplasma laidlawii and Mycoplasma pulmonis. Science 235:1392-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dybvig, K., C. T. French, and L. L. Voelker. 2000. Construction and use of derivatives of transposon Tn4001 that function in Mycoplasma pulmonis and Mycoplasma arthritidis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4343-4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dybvig, K., and A. Woodard. 1992. Construction of recA mutants of Acholeplasma laidlawii by insertional inactivation with a homologous DNA fragment. Plasmid 28:262-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fadiel, A., K. D. Eichenbaum, N. El Semary, and B. Epperson. 2007. Mycoplasma genomics: tailoring the genome for minimal life requirements through reductive evolution. Front. Biosci. 12:2020-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French, C. T., P. Lao, A. E. Loraine, B. T. Matthews, H. Yu, and K. Dybvig. 2008. Large-scale transposon mutagenesis of Mycoplasma pulmonis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:67-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass, J. I., N. Assad-Garcia, N. Alperovich, S. Yooseph, M. R. Lewis, M. Maruf, C. A. Hutchison III, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 2006. Essential genes of a minimal bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:425-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halbedel, S., and J. Stulke. 2007. Tools for the genetic analysis of Mycoplasma. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchison, C. A., S. N. Peterson, S. R. Gill, R. T. Cline, O. White, C. M. Fraser, H. O. Smith, and J. C. Venter. 1999. Global transposon mutagenesis and a minimal Mycoplasma genome. Science 286:2165-2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janis, C., C. Lartigue, J. Frey, H. Wroblewski, F. Thiaucourt, A. Blanchard, and P. Sirand-Pugnet. 2005. Versatile use of oriC plasmids for functional genomics of Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capricolum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2888-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannan, T. R., and J. B. Baseman. 2006. ADP-ribosylating and vacuolating cytotoxin of Mycoplasma pneumoniae represents unique virulence determinant among bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:6724-6729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King, K. W., and K. Dybvig. 1994. Mycoplasmal cloning vectors derived from plasmid pKMK1. Plasmid 31:49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krause, D. C., and M. F. Balish. 2004. Cellular engineering in a minimal microbe: structure and assembly of the terminal organelle of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 51:917-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lartigue, C., A. Blanchard, J. Renaudin, F. Thiaucourt, and P. Sirand-Pugnet. 2003. Host specificity of mollicutes oriC plasmids: functional analysis of replication origin. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6610-6618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lartigue, C., S. Vashee, M. A. Algire, R. Y. Chuang, G. A. Benders, L. Ma, V. N. Noskov, E. A. Denisova, D. G. Gibson, N. Assad-Garcia, N. Alperovich, D. W. Thomas, C. Merryman, C. A. Hutchison III, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, and J. I. Glass. 2009. Creating bacterial strains from genomes that have been cloned and engineered in yeast. Science 325:1693-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leach, R. H., H. Erno, and K. J. MacOwan. 1993. Proposal for designation of F38-type caprine mycoplasmas as Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capripneumoniae subsp. nov. and consequent obligatory relegation of strains currently classified as M. capricolum (Tully, Barile, Edward, Theodore, and Erno 1974) to an additional new subspecies, M. capricolum subsp. capricolum subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:603-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, S. W., G. F. Browning, and P. F. Markham. 2008. Development of a replicable oriC plasmid for Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma imitans, and gene disruption through homologous recombination in M. gallisepticum. Microbiology 154:2571-2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manso-Silvan, L., E. M. Vilei, K. Sachse, S. P. Djordjevic, F. Thiaucourt, and J. Frey. 2009. Mycoplasma leachii sp. nov. as a new species designation for Mycoplasma sp. bovine group 7 of Leach, and reclassification of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides LC as a serovar of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:1353-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogasawara, N., S. Moriya, and H. Yoshikawa. 1991. Initiation of chromosome replication: structure and function of oriC and DnaA protein in eubacteria. Res. Microbiol. 142:851-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilo, P., J. Frey, and E. M. Vilei. 2007. Molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC. Vet. J. 174:513-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocha, E., P. Sirand-Pugnet, and A. Blanchard. 2005. Genome analysis: recombination, repair, and recombinational hotspots, p. 31-73. In A. Blanchard and G. Browning (ed.), Mycoplasmas: molecular biology, pathogenicity, and strategies for control. Horizon Bioscience, Hethersett, United Kingdom.

- 32.Rocha, E. P., and A. Blanchard. 2002. Genomic repeats, genome plasticity and the dynamics of Mycoplasma evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2031-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tully, J. G., D. L. Rose, R. F. Whitcomb, and R. P. Wenzel. 1979. Enhanced isolation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat washings with a newly-modified culture medium. J. Infect. Dis. 139:478-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voelker, L. L., and K. Dybvig. 1998. Transposon mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 104:235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitley, J. C., and L. R. Finch. 1989. Location of sites of transposon Tn916 insertion in the Mycoplasma mycoides genome. J. Bacteriol. 171:6870-6872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.