Abstract

Cyanobacteria use sunlight and water to produce hydrogen gas (H2), which is potentially useful as a clean and renewable biofuel. Photobiological H2 arises primarily as an inevitable by-product of N2 fixation by nitrogenase, an oxygen-labile enzyme typically containing an iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMo-co) active site. In Anabaena sp. strain 7120, the enzyme is localized to the microaerobic environment of heterocysts, a highly differentiated subset of the filamentous cells. In an effort to increase H2 production by this strain, six nitrogenase amino acid residues predicted to reside within 5 Å of the FeMo-co were mutated in an attempt to direct electron flow selectively toward proton reduction in the presence of N2. Most of the 49 variants examined were deficient in N2-fixing growth and exhibited decreases in their in vivo rates of acetylene reduction. Of greater interest, several variants examined under an N2 atmosphere significantly increased their in vivo rates of H2 production, approximating rates equivalent to those under an Ar atmosphere, and accumulated high levels of H2 compared to the reference strains. These results demonstrate the feasibility of engineering cyanobacterial strains for enhanced photobiological production of H2 in an aerobic, nitrogen-containing environment.

Photobiologically produced hydrogen gas (H2) is a clean energy source with the potential to greatly supplement our use of fossil fuels (39). Whereas coal and oil are limited, cyanobacteria and eukaryotic microalgae can use inexhaustible sunlight as the energy source and water as the electron donor to produce H2 (42). This gas is generated either by hydrogenases (52) or as an inevitable by-product of N2 fixation by nitrogenases (49). In contrast to the reaction of hydrogenases which is reversible, nitrogenases catalyze the unidirectional production of H2, although with substantial energy input in the form of ATP (47). Under optimal N2-fixing conditions: N2 + 8 e− + 8 H+ + 16 ATP → H2 + 2 NH3 + 16 (ADP + Pi), whereas, in the absence of N2 (e.g., under Ar), all electrons are allocated to proton reduction: 2 e− + 2 H+ + 4 ATP → H2 + 4 (ADP + Pi). Thus, one expects to be able to increase the H2 production activity of nitrogenase by decreasing the electron allocation to N2 fixation.

Nitrogenases are sensitive to inactivation by O2; however, N2-fixing cyanobacteria have developed mechanisms to protect these enzymes from photosynthetically generated oxygen (5). Of particular interest, Anabaena (also known as Nostoc) sp. strain PCC 7120 and some other filamentous cyanobacteria respond to combined-nitrogen deprivation by undergoing differentiation in which a subset of cells become heterocysts that provide a microaerobic environment, allowing nitrogenase to function in aerobic culture conditions. The nitrogenase-related (nif) genes are specifically expressed in heterocysts which lack O2-evolving photosystem II activity and are surrounded by a thick cell envelope composed of glycolipids and polysaccharides that impede the entry of O2 (56). Vegetative cells perform oxygenic photosynthesis and fix CO2. Heterocysts obtain carbohydrates from those cells and, in turn, provide them with fixed nitrogen.

The molybdenum-containing nitrogenase of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 consists of the Fe protein (encoded by nifH) and the MoFe protein (encoded by nifD and nifK). As in other organisms, the Fe protein is a homodimer containing a single [4Fe-4S] cluster and functions as an ATP-dependent electron donor to the MoFe protein. The latter is an α2β2 heterotetramer with each nifD-encoded α subunit coordinating the FeMo cofactor (FeMo-co; MoFe7S9X-homocitrate) that binds and reduces substrate, while α plus the nifK-encoded β subunits coordinate the [8Fe-7S] P-cluster (14). Additional nif genes are required for the biosynthesis of the metal clusters and maturation of the enzyme (40). The major nif gene cluster of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 undergoes two rearrangements in the heterocyst to yield nifB-fdxN-nifSUHDK-(1 ORF)-nifENX-(2 ORFs)-nifW-hesAB-fdxH (19).

One approach to increase H2 production by nitrogenase is to enhance the electron flux to proton reduction and away from N2 reduction. Although replacement of N2 by Ar is effective for increasing H2 production, this approach increases the operational cost for large-scale generation of H2. Mutagenesis offers an alternative mechanism to overcome N2 competition. The amino acid sequences of the MoFe α subunit are highly conserved among different phyla (18). The V75I substitution in the suspected gas channel of NifD2 of Anabaena variabilis (equivalent to V70 in A. vinelandii) resulted in greatly diminished N2 fixation, while allowing for H2 production rates (under N2) that were similar to those of wild-type cells under Ar (55). Significantly, however, the nonheterocyst nitrogenase of this strain, which is expressed mainly in vegetative cells under anaerobic conditions, is incompatible with O2-evolving photosynthesis and thus requires continuous anaerobic conditions along with a supply of exogenous reducing sugars for H2 production. Substitutions of selected amino acids in the vicinity of the FeMo-co active site within Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase were shown to eliminate or greatly diminish N2 fixation while, in some cases, allowing for effective proton reduction (2, 10, 17, 27, 36, 44, 45, 48). Therefore, certain amino acid exchanges near FeMo-co might produce variant MoFe proteins in heterocyst-forming Anabaena that redirect the electron flux through the enzyme preferentially to proton reduction so as to synthesize more H2 in the presence of N2 in an aerobic environment.

To examine whether Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 nitrogenase can be modified to increase photobiological H2 production by effecting such a redirection, we evaluated in vivo H2 production and acetylene reduction rates of a series of cyanobacterial nifD site-directed mutants. We mutated six NifD residues (Fig. 1) predicted to lie within 5 Å of FeMo-co to create 49 variants using an Anabaena ΔNifΔHup (previously denoted ΔhupL) parental strain that lacks both an intact nifD and an uptake hydrogenase (34). In an atmosphere containing N2 and O2, several mutants exhibited significantly enhanced rates of in vivo H2 production and accumulated high levels of H2 compared to the reference strains.

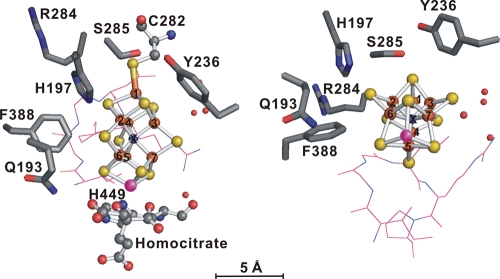

FIG. 1.

Side-on (left) and Mo end-on (right) views of the predicted active site for nitrogenase of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. The FeMo-co cluster, a [7Fe-8S-Mo-X-homocitrate] complex, where X is a central unidentified light atom (N, C, or O), and its two coordinating residues (C282 and H449) are shown in a ball-and-stick representation. Water molecules near the FeMo-co are indicated by isolated spheres in red. The side chains of the residues targeted for mutagenesis—Q193, H197, Y236, R284, S285, and F388—are shown in stick representation. Residues V362 through P367 are represented by lines. The Anabaena residues were mapped onto the corresponding residues from the crystal structure of the A. vinelandii enzyme (PDB file 1M1N). The figure was generated by using PyMOL (www.pymol.org/), with the following color scheme: Fe, orange; S, yellow; C, gray; N and central atom X, blue; O, red; and Mo, pink.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in the present study are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Cyanobacterial strains were grown in an 8-fold dilution of Allen and Arnon (AA/8) liquid medium or nondiluted AA agar (1) with (or without) added nitrate on a rotary shaker under continuous illumination (30 [or, where indicated, 60 to 70] μmol photons m−2 s−1 of photosynthetically active radiation) at 30°C. Escherichia coli strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium at 37°C. The media for selection and maintenance of Anabaena and E. coli contained the appropriate antibiotics as described previously (34).

E. coli HB101(pRL623) (15) and J53 (RP4) (53) were used for the transfer of mobilizable plasmids into Anabaena cells by conjugation via triparental mating (16). To permit evaluation of the in vivo H2-producing activity of variant nitrogenases, ΔHup Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (34), impaired in H2 uptake activity, was used as the parental strain.

The chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentration of the cultures was determined by the method of Porra (38), as previously described (34). The cell dry weight (CDW) was determined by filtering aliquots of the cultures through glass fiber filters (Whatman 934-AH; Fisher Scientific), washing with an equal volume of distilled water, and drying the samples at 80°C for 24 h.

Construction of plasmids and Anabaena variants.

Our series of constructions, summarized in Fig. 2 and described in Table S1 in the supplemental material, was based on the complete genomic sequence of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (25), obtained from the Kazusa database (http://genome.kazusa.or.jp/cyanobase/Anabaena/).

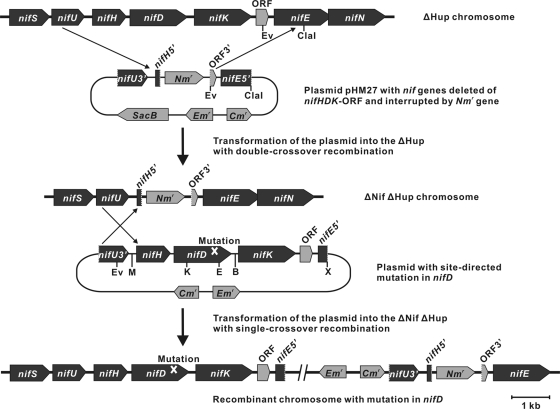

FIG. 2.

Construction of the ΔNifΔHup, complemented, and nifD site-directed mutant strains of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. A region of the nifHDK-ORF genes was deleted from the parental ΔHup chromosome by gene replacement through a double-crossover event with pHM27 (top). The ΔHup strain used for this construction lacks an 11-kb nifD element containing the xisA recombinase gene, unlike the wild-type strain with the nifD interruption (19). After verification of the deletion and complete segregation of the nifHDK-ORF region in the selected ΔNifΔHup mutant, plasmids containing the nifHDK-ORF, with or without a site-directed mutation in nifD, was integrated at the nifU3′-nifH5′ locus into the deletion mutant chromosome through a single-crossover event, yielding strains complemented by wild-type nifH, nifD, nifK, and ORF(all1439) genes or by variants whose nifD genes have site-directed mutations, respectively (middle). Homologous recombination occurred preferentially between the nifU3′-nifH5′ regions rather than between the ORF3′-nifE5′ regions due to the longer sequence length of the former (1,136 bp) than the latter (673 bp). The genome organization of the resulting single-crossover recombinants is shown at the bottom.

Cloning of the nif region was achieved by combining fragments, initially a 2.7-kb EcoRV-nifU3′-nifH-nifD5′-EcoRI fragment (see pHM1) and a 5.9-kb EcoRI-nifD3′-nifK-ORF-nifEN-nifX5′-EcoRI fragment that is adjacent to it in heterocyst genomic DNA. In vegetative cells, the latter fragment normally bears an excision element that is excised from the chromosome in heterocysts (19). To obtain the 5.9-kb fragment, plasmid pHM6 was first integrated at the nifNX locus in the Anabaena wild-type chromosome to create mutant AnNifNX. Genomic DNA was extracted from heterocysts isolated from that mutant, digested with EcoRI, recircularized by self-ligation, and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ with selection on an LB agar plate containing 50 μg of kanamycin (Km) ml−1. A transformant contained a desired plasmid, denoted pHM7. The insert in pHM7, combined with pHM1, yielded pHM10 and was then reduced in size, producing pHM11. Because it was unclear whether the 556-bp promoter sequence upstream of nifH in pHM11 would suffice for the wild-type activity of nitrogenase (4), the region upstream of nifH was elongated, yielding pHM13.

The Anabaena strain into which mutated versions of nifD were transferred for testing was denoted ΔNifΔHup. Its provenance from the ΔHup mutant by mutation with plasmid pHM27 is shown in Fig. 2. Single and double recombinants were screened as previously described (33, 34). The deletion of nifHDK-ORF in the ΔNifΔHup chromosome was confirmed by Southern blotting using probes for nifUH, nifD1 (35), and the npt (Kmr/Nmr) gene (34), as well as by PCR with the primer pairs nifD-F1/nifD-R2, nifK-F/nifK-R, and nifHDK-ORF-F/nifHDK-ORF-R (data not shown).

To facilitate replacement of nifD with its mutated versions and for ease of sequencing to confirm the presence of the introduced mutations (and absence of unwanted mutations), a BamHI site was introduced into the nifD-nifK intergenic region. To this end, the sequence GGAACC was changed to GGATCC by overlap extension PCR (21): two PCR fragments, separately generated with the primer pairs nifD-F/nifDK-BamHI-R and nifDK-BamHI-F/nifK-R on template pHM13, were used as megaprimers to fuse these fragments. The product, amplified by PCR with the primer pairs nifD-F/nifK-R was cloned, yielding pHM14. An internal, 1.0-kb EcoRI-Bsp1407I piece of the cloned fragment, transferred into pHM13, produced pHM15. To obtain desired, unique sites, XbaI-nifU3′-nifHDK-ORF-nifE5′-XhoI was transferred to pSFI (41) and then, as a SacI-SalI fragment, to pRL271 (6), producing plasmid pHM19. Introduction of pHM19 into the ΔNifΔHup strain by conjugation resulted in recovery of an Emr recombinant strain, capable of N2 fixation, denoted AnNifHΔHup.

Colony hybridization, Southern hybridization, and detection of probes were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). The hybridization probes used were synthesized by PCR amplification using the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The proper construction of plasmids pHM4, pHM12a, pHM14, and pHM23 were confirmed by sequencing.

Site-directed mutagenesis of nifD.

Introduction of site-directed mutations into nifD was performed using primer pairs listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material with a QuikChange II kit (Stratagene, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's directions. The 0.83-kb KpnI-EcoRI and 1.2-kb KpnI-BamHI nifD fragments of pHM16 were cloned into pBluescript II SK(+) digested with the same enzymes to yield pHM18 and pHM22, which code for the regions from residue 112 to 388 in NifD of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (corresponding to residues 110 to 381 in NifD of A. vinelandii) and from residue 112 to the end of NifD, respectively. Plasmids pHM18 and pHM22 were used as templates for the introduction of mutations involving Q193, H197, Y236, R284, and S285 or that of F388, respectively; the mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. To eliminate the possibility that the wild-type version of nifD remained after attempted replacement with the mutated version, the internal sequence of nifD flanked by KpnI and EcoRI sites was replaced by the 1.3-kb, npt-bearing KpnI-EcoRI fragment of pHM17b, yielding plasmid pHM20. The 0.83-kb KpnI-EcoRI and 1.2-kb KpnI-BamHI fragments of derivatives of pHM18 and pHM22 containing the nifD mutations were ligated into pHM20 digested with the same enzymes, respectively, displacing the npt cassette. The resulting plasmids were digested with SacI and SalI and the 6.6-kb SacI-SalI fragments bearing the mutated versions of nifHDK genes were ligated into pRL271 digested with SacI and XhoI. The products were introduced into the ΔNifΔHup strain by conjugation. Single-crossover variants with the desired site-directed mutations in nifD were selected (Fig. 2). The sites of crossover were verified to lie within nifUH by PCR amplification using the primers shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

H2 production and acetylene reduction assays.

For induction of Anabaena nitrogenase, cells grown in AA/8-plus-nitrate medium illuminated with 30 μmol photons m−2 s−1 were washed with AA/8, suspended in 250 ml of AA/8 medium at a Chl a concentration of 0.5 to 0.6 mg liter−1, and grown autotrophically with N2 as the sole source of nitrogen under a light intensity of 60 to 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Two and 3 days after combined-nitrogen step-down, 100 and 100 to 150 ml of cultures, respectively, were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in AA/8 medium, respectively. Portions (2 ml) of the samples (ca. 2 to 6 μg of Chl a ml−1) were transferred to 9.0-ml flasks and sealed with polytetrafluoroethylene/silicone septa (Supelco). The flasks were illuminated (intensity, 60 to 65 μmol photons m−2 s−1) on a rotary shaker for about 1 to 1.5 h, and the headspace gas was then replaced with argon (Ar) or air for assay of the H2 production rate. In separate assays, the rates of reduction of acetylene by septum-sealed, combined-nitrogen deprived samples were determined by adding C2H2 to a final concentration of 12% (vol/vol) in Ar and illuminated as described above. Duplicate or triplicate samples were prepared for each variant. After 2 to 3 h of incubation under illumination, the concentration of H2 in the headspace was measured by gas chromatography (GC; Trace GC Ultra, Thermo Scientific) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and using a molecular sieve 5A capillary column (30 m, 0.53-mm inner diameter; Restec, Bellefonte, PA). Similarly, ethylene and ethane were measured by GC (Shimadzu GC-8A) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a Porapak N-packed column (80/100 mesh, 2 m by 1/8 in.). The rates of H2 production and acetylene reduction to ethylene and ethane were normalized to Chl a.

Assays of H2 accumulation.

For H2 accumulation experiments, cells grown in AA/8-plus-nitrate medium (23) illuminated at 60 to 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1 from cool white fluorescent lamps were transferred to 250 ml AA/8 medium at a Chl a concentration of about 1.0 mg liter−1 and grown for 1 day to induce formation of heterocysts and synthesis of nitrogenase. Then, 8-ml portions of the nitrogenase-derepressed culture with 30 μg of Chl a were transferred into 30-ml crimp-top vials and sealed with a butyl rubber stopper. All vials were flushed with Ar or N2 for 10 to 15 min, and CO2 was then added to the headspace of each vial to a final concentration of 5%. Duplicate samples under Ar + 5% CO2 or N2 + 5% CO2 were prepared for each variant culture, which were incubated on a rotary shaker under continuous illumination (60 to 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1) at 30°C. The amount of H2 accumulated in the headspace was measured by using a TCD-equipped GC (Trace GC Ultra; Thermo Scientific).

RESULTS

The residues targeted for mutagenesis in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 nitrogenase (Fig. 1) were identified after mapping the cyanobacterial NifD and NifK sequences onto the high-resolution (1.16 Å) structure of A. vinelandii MoFe protein (PDB file 1M1N) (14). The corresponding sequences of the two microorganisms are 68 and 55% identical, with even greater identity in the region near the active site (47 of 48 residues identical within 8 Å of FeMo-co). The structure predicts that portions of 19 residues, all highly conserved and encoded by nifD, lie within 5 Å of FeMo-co. Residues C275 and H442 of A. vinelandii nitrogenase anchor FeMo-co to the polypeptide by coordinating its terminal Fe and Mo atoms, respectively, and residues 355 to 360 (IGGLRP) in the A. vinelandii enzyme have been suggested to be important for proper insertion of FeMo-co into the protein (11). Therefore, the corresponding residues in Anabaena NifD (C282, H449, and residues 362 to 367; VGGLRP) were left unchanged. In contrast, we carried out an extensive survey of changes to residues Q193, H197, R284, and F388 in the Anabaena enzyme, equivalent to residues (Q191, H195, R277, and F381) that were previously substituted in a limited fashion in the A. vinelandii protein (17, 27, 36, 44, 45, 48). Two additional residues lying within 5 Å of FeMo-co in the A. vinelandii enzyme (Y229 and S278) were substituted in the Anabaena sequence (Y236 and S285). Each of the selected six residues was replaced by nonpolar, polar, or charged residues by using a parental Anabaena strain with ΔNif and ΔHup mutations (34), the latter to eliminate H2 uptake. In all, 49 NifD variants were constructed: 8 for Q193, 13 for H197, 7 for Y236, 9 for R284, 8 for S285, and 4 for F388.

Diazotrophic growth and H2 production rates.

The 49 variants, the parental ΔNifΔHup and ΔHup strains, and the control AnNifΔHup strain (a wild type-nifHDK-ORF-complemented variant of the ΔNifΔHup mutant) were tested for diazotrophic growth at low light intensity (20 μmol photons m−2 s−1) on AA agar medium (1) lacking combined nitrogen. Strains shown to be capable of diazotrophic growth were analyzed for their rates of growth (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and their specific growth rates were tabulated (Table 1). The control AnNifΔHup strain displayed essentially normal diazotrophic growth that was only slightly reduced from the parental ΔHup strain that was its predecessor, indicating that after transformation and single-crossover recombination the plasmid carrying the wild-type nifHDK-ORF genes was able to restore the N2 fixation phenotype to the ΔNifΔHup deletion mutant. Only 9 NifD variants were capable of significant diazotrophic growth, with 1- to 3-day variations in the lag period before exponential growth was observed. The Q193A and Y236F variants were unchanged from the control AnNifΔHup strain, only very small reductions in specific growth rates were observed for five variants (Y236T, Y236H, S285A, S285T, and S285C), and clearly decreased rates were observed for the Y236M and R284K mutants. The other NifD variants, including all H197 variants, were incapable of diazotrophic growth. In contrast, all of the strains grew normally in the presence of nitrate.

TABLE 1.

Abilities of 3 control strains and 49 NifD variants to grow on N2, the rates of H2 production by those strains under Ar or air, and the ratios of those rates at 2 days after combined-nitrogen step-downa

| Strain | N2-fixing specific growth rates (h−1)b | Avg H2 production rate (μmol mg of Chl a−1 h−1) ± SD |

Avg percentage of rates under air relative versus those under Ar ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under Ar | Under air | |||

| Predecessor and control strains | ||||

| ΔNifΔHup | - | NDc | ND | |

| ΔHup | 0.26 | 17.4 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 41 ± 4 |

| AnNifΔHup | 0.22 | 22.1 ± 1.9 | 10.6 ± 0.6 | 48 ± 5 |

| Variants of NifDΔHup | ||||

| Q193G | - | 9.1 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 26 ± 5 |

| Q193A | 0.21 | 20.8 ± 1.6 | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 48 ± 4 |

| Q193S | - | 20.8 ± 1.5 | 19.7 ± 3.8 | 95 ± 20 |

| Q193V | - | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 0.49 ± 0.08 | 10 ± 2 |

| Q193L | - | 20.9 ± 2.3 | 20.2 ± 1.8 | 97 ± 14 |

| Q193N | - | 16.0 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 22 ± 4 |

| Q193H | - | 16.9 ± 2.0 | 24.2 ± 2.7 | 143 ± 24 |

| Q193K | - | 9.1 ± 1.4 | 7.6 ± 1.9 | 83 ± 24 |

| H197G | - | 17.0 ± 3.2 | 11.4 ± 2.8 | 67 ± 21 |

| H197A | - | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 0.79 ± 0.30 | 28 ± 14 |

| H197S | - | 4.1 ± 0.4 | ND | |

| H197T | - | 21.3 ± 1.9 | 20.7 ± 3.8 | 97 ± 20 |

| H197L | - | 14.9 ± 4.8 | 7.9 ± 2.9 | 53 ± 26 |

| H197F | - | 15.4 ± 3.8 | 14.5 ± 2.9 | 94 ± 30 |

| H197Y | - | 7.6 ± 3.3 | 4.7 ± 2.4 | 62 ± 42 |

| H197D | - | 10.0 ± 2.9 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 59 ± 26 |

| H197E | - | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 53 ± 33 |

| H197N | - | 10.6 ± 4.6 | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 25 ± 18 |

| H197Q | - | 20.2 ± 3.6 | 10.4 ± 3.1 | 52 ± 18 |

| H197K | - | 5.6 ± 1.8 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 73 ± 47 |

| H197R | - | ND | ND | |

| Y236A | - | 10.9 ± 3.8 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 9 ± 4 |

| Y236T | 0.16 | 20.8 ± 0.9 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 59 ± 4 |

| Y236M | 0.062 | 14.2 ± 3.0 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 32 ± 14 |

| Y236F | 0.22 | 15.7 ± 1.5 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 33 ± 4 |

| Y236D | - | 10.2 ± 3.9 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 26 ± 16 |

| Y236N | - | 15.1 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 38 ± 2 |

| Y236H | 0.18 | 16.3 ± 4.9 | 7.8 ± 3.4 | 48 ± 25 |

| R284T | - | 9.4 ± 2.0 | 8.1 ± 2.1 | 86 ± 35 |

| R284C | - | 11.7 ± 2.2 | 7.9 ± 2.6 | 67 ± 25 |

| R284L | -* | 13.8 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 31 ± 11 |

| R284F | -* | 14.6 ± 1.6 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 32 ± 6 |

| R284Y | - | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.48 ± 0.24 | 23 ± 14 |

| R284E | - | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 0.79 ± 0.78 | 41 ± 54 |

| R284Q | -* | 10.2 ± 2.7 | 5.8 ± 2.5 | 57 ± 29 |

| R284H | - | 16.0 ± 2.9 | 19.4 ± 5.3 | 121 ± 40 |

| R284K | 0.087 | 15.6 ± 0.7 | 7.9 ± 1.6 | 51 ± 11 |

| S285G | -* | 8.4 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 30 ± 16 |

| S285A | 0.16 | 16.1 ± 2.9 | 6.1 ± 1.4 | 38 ± 11 |

| S285T | 0.17 | 19.9 ± 1.4 | 9.5 ± 0.8 | 48 ± 5 |

| S285C | 0.17 | 22.3 ± 3.1 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 31 ± 8 |

| S285M | - | ND | ND | |

| S285D | - | ND | ND | |

| S285N | - | 10.3 ± 1.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 14 ± 5 |

| S285Q | - | ND | ND | |

| F388A | - | 11.8 ± 2.3 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 52 ± 18 |

| F388T | - | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 53 ± 22 |

| F388Y | - | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 81 ± 24 |

| F388H | - | 12.6 ± 1.8 | 16.0 ± 3.6 | 127 ± 34 |

Values are averages of three to six independent experiments, each performed with duplicate or triplicate samples. H2 production rates may be overestimated in some strains due to partial decomposition of Chl a (see Table 2). The strains indicated in boldface were studied in H2 accumulation experiments.

The ability to grow diazotrophically initially was tested by growth on AA agar plates lacking combined nitrogen for about 1 month. Cultures capable of diazotrophic growth were further analyzed to obtain growth curves in liquid culture as depicted in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. The specific growth rates obtained from that experiment are tabulated here. A replicate experiment yielded analogous results. -, not detected. *, spontaneous mutant revertant colonies that grow on N2 were noted after 1 month.

ND, not detected or <0.15 μmol H2 mg Chl a−1 h−1.

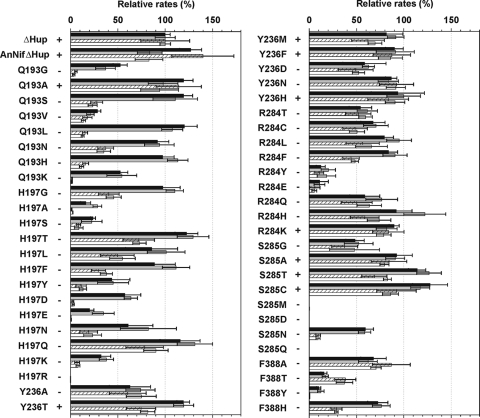

The in vivo H2 production rates of the NifD variants and two reference strains were measured at 2 and 3 days after combined-nitrogen step-down under Ar or air (Table 1 and Fig. 3; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). These tables also list the air/Ar H2 production rate percentages as a rough estimate of the effects of the competing N2 substrate on the variant nitrogenases. The ΔHup and AnNifΔHup strains were similar in exhibiting rates under air that were 30 to 50% of those under Ar, a finding consistent with inhibition of H2 production by N2, as is typical of the wild-type nitrogenase (49). Some variants produced H2 at rates similar to the reference strains for the two conditions, also indicating inhibition of H2 production by N2, while others possessed highly diminished or nondetectable levels of proton reduction. Of greater interest, certain of the NifD variants exhibited H2 production rates under air that were comparable to those under Ar, suggesting that N2 does not greatly inhibit H2 production by these mutant nitrogenases. The H2 production rates for some variants under air were dramatically greater than the reference strains, in several cases reaching values similar to those of the reference strains under Ar when measured on a per-Chl a basis. As described in the section on quantification of CDW versus Chl a content, this approach may overestimate H2 production rates in some cases where Chl a is partially degraded. Nevertheless, three variants (Q193H, R284H, and F388H) exhibited equivalent or higher rates under air (or 100% N2; see Table S4 in the supplemental material) than under Ar.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of nitrogen-fixing ability, H2 production rates, and reduction rates of acetylene (under Ar) of the 49 NifD variants and control strains at 2 and 3 days after combined-nitrogen step-down. N2-fixing phenotypes are shown as + or -, with the actual specific growth rates provided in Table 1. The percentages of production rates of H2 and ethylene relative to those of the parental ΔHup strain were obtained by using the data from Tables S3 and S4 in the supplemental material, respectively. The relative rates of H2 production analyzed at 2 days (filled bars) and 3 days (gray bars) after combined-nitrogen step-down are shown; the relative rates of C2H2 reduction to C2H4 determined at 2 days (dashed bars) and 3 days (open bars) after nitrogen step-down are also indicated.

Acetylene reduction rates.

Table S5 in the supplemental material reports the rates of reduction of acetylene (12% in Ar) to ethylene and ethane by the 49 NifD variants and the two reference strains at 2 and 3 days after nitrogen step-down. The reduction of acetylene to ethylene often is used as a surrogate to assay nitrogenase activity, and the data indicate a wide range of such activity in the NifD variants. Notably, whereas cells containing the wild-type nitrogenase catalyzed only the two-electron reduction of acetylene, 18 of the 49 NifD mutants reduced this substrate to both ethylene and ethane, the latter requiring a four-electron reduction. For most of the ethane-producing variants, this gas was detected as only a minor product; however, the Q193K and H197N variants produced ethane at nearly one-half and one-quarter the rates, respectively, of ethylene formation.

Correlations among the abilities to fix N2, produce H2, and reduce acetylene to ethylene.

To more readily compare the NifD variants in terms of their N2 fixation phenotypes, H2 production rates under Ar, and rates of acetylene reduction to ethylene, the data are combined in Fig. 3. The nine variants capable of growing well diazotrophically (Q193A, Y236T, Y236M, Y236F, Y236H, R284K, S285A, S285T, and S285C) all exhibited relatively high rates of acetylene reduction activity and large rates of H2 production under Ar (62 to 114% and 82 to 128%, respectively, of their predecessor ΔHup strain). In contrast, 15 variants (H197G, H197T, H197L, H197Q, Y236A, Y236D, Y236N, R284T, R284C, R284L, R284F, R284Q, R284H, S285G, and F388A) were severely impaired in or incapable of diazotrophic growth, and yet they retained ∼50% or more of the ΔHup strain rates of both acetylene reduction and H2 production under Ar. Another 12 variants (Q193G, Q193S, Q193L, Q193N, Q193H, Q193K, H197D, H197F, H197Y, H197N, S285N, and F388H) exhibited nearly half or more of the ΔHup strain H2 production rate under Ar, but their acetylene reduction rates were well below 50% of the ΔHup strain. The remaining 13 variants reached less than 40% of the rates for either acetylene reduction or H2 production compared to the ΔHup strain; only four strains (H197R, S285M, S285D, and S285Q) were essentially inactive for these activities. In general, changes in the FeMo-co environment more greatly affected acetylene reduction rates than H2 production rates under Ar. Less acetylene reduction can account for an increase in H2 production, as reported previously using the A. vinelandii enzyme (17, 44). The striking exception to this generalization is the F388T strain, which exhibited less than 20% of the control H2 production rate while retaining nearly 40% of acetylene reduction rate.

Accumulation of H2 in atmospheres of Ar or N2.

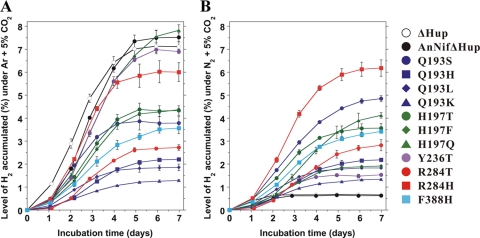

Eleven NifD variants were selected for long-term H2 accumulation studies. These mutants exhibited substantial increases over the two reference strains in their air/Ar H2 production rates and most demonstrated increased rates under air compared to the ΔHup strains on the basis of Chl a (Table 1; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). The strains were incubated in sealed vials using an atmosphere of Ar + 5% CO2 or N2+5% CO2 and assayed for H2 accumulation over 7 days (Fig. 4). All selected variant cultures produced H2 continuously from 1 day to 4 to 6 days, at which point the H2 concentrations leveled off at ca. 1 to 8%, depending on the cultures and conditions utilized. The H197Q and Y236T cultures exhibited profiles similar to those of the two reference strains under Ar + CO2 and reached the highest maximum levels of H2 (ca. 7 to 8%), which is consistent with the observation that these four strains had similar phenotypes with respect to H2 production rates under Ar and air (Table 1; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). However, when the reference strain cultures were grown under N2 + 5% CO2, the H2 gas concentrations in the headspace leveled off at <1%, whereas all variant cultures accumulated significantly higher levels of H2. Of the variants tested, the R284H culture exhibited the most dramatically increased levels of accumulated H2 compared to the reference strain cultures when grown under N2. This mutant strain reached 87% (two independent experiments) of the levels of H2 accumulated by the reference strains under Ar at 5 to 7 days. The percentage of H2 accumulated under N2 versus that under Ar was compared for all 11 variant and 2 control strains at each time point in Table S6 in the supplemental material. With the exception of the H197F, H197Q, Y236T, and reference strains, the selected variant cultures accumulated approximately the same levels of H2 under Ar as under N2. These results are consistent with their similar H2 production rates in air versus Ar, ranging from 82 to 143% at 2 days after nitrogen step-down (Table 1), and indicate that N2 does not inhibit H2 production by these variant cultures for time periods of at least a week. Whereas the H2 accumulation rates of the R284H, H197Q, and Y236T cultures closely paralleled those of the reference strains under Ar during the first 4 days, the other NifD variant cultures exhibited significantly decreased accumulation rates.

FIG. 4.

H2 accumulation by 11 NifD variants and two reference strains under Ar + 5% CO2 (A) and N2+5% CO2 (B). Culture samples in sealed vials were incubated at 30°C under continuous illumination (60 to 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1) over 7 days. The initial concentration of the sample in each vial was 3.75 μg of Chl a ml−1 (30 μg of Chl a in 8 ml). The initial composition and volume of the headspace gas were Ar + 5% CO2 or N2 + 5% CO2 in 22 ml. H2 concentrations were measured by GC. The figure shows the results of typical experiments with each value representing the average ± the standard deviation of duplicate samples.

Quantification by CDW versus Chl a content.

The H2, ethylene, and ethane production rates and H2 accumulation comparisons described above were all based on the assumption that the mutant strains contained comparable levels of Chl a regardless of the different incubation conditions. To test this hypothesis and to allow comparison with such measurements in other species, cultures incubated for 7 days under N2 + 5% CO2 or Ar + 5% CO2 were examined for both Chl a content and CDW (Table 2). The CDW measurements were very constant among the cultures, regardless of the incubation conditions. In contrast, the Chl a content varied nearly 2-fold for the reference strains and the Y236T variant when Ar versus N2 incubation was compared. Although for some cultures the results may lead to overestimation of the gas production rates or levels of H2 accumulation, we used cultures harvested at 1 day after nitrogen step-down, when the concentration of Chl a would be minimally affected.

TABLE 2.

Cell dry weight, Chl a content, and Chl a/cell dry weight ratios by selected variants after 7 days of incubation under Ar + 5% CO2 and N2 + 5% CO2a

| Strain | Avg ± SD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDW (mg) |

Chl a (μg) |

Chl a/CDW (mg/g) |

||||

| Under Ar | Under N2 | Under Ar | Under N2 | Under Ar | Under N2 | |

| ΔHup | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 19 ± 1.6 | 39 ± 1.1 | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 16 ± 1.0 |

| AnNifΔHup | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 19 ± 3.5 | 39 ± 0.4 | 7.7 ± 1.7 | 14 ± 0.5 |

| Q193S | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 25 ± 0.7 | 32 ± 2.9 | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 11 ± 1.5 |

| Q193H | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 23 ± 2.1 | 23 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 0.5 |

| Q193L | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 1.0 | 24 ± 0.4 | 10 ± 0.9 | 9.3 ± 0.4 |

| Q193K | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 3.7 | 24 ± 2.3 | 10 ± 1.8 | 9.1 ± 0.7 |

| H197T | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 4.5 | 22 ± 3.5 | 8.5 ± 2.0 | 8.8 ± 1.5 |

| H197F | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 24 ± 1.9 | 24 ± 1.0 | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 9.3 ± 0.7 |

| H197Q | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 19 ± 1.6 | 22 ± 1.9 | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 1.2 |

| Y236T | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 19 ± 3.8 | 39 ± 1.3 | 7.2 ± 1.7 | 15 ± 1.2 |

| R284T | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 20 ± 4.8 | 24 ± 3.8 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 8.7 ± 1.8 |

| R284H | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 24 ± 0.1 | 26 ± 2.3 | 8.7 ± 1.8 | 9.0 ± 0.7 |

| F388H | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 3.1 | 8.7 ± 2.6 | 8.4 ± 1.0 |

Values are averages of two independent experiments, each performed with duplicate samples. The initial average cell dry weight (CDW), Chl a, and Chl a/CDW of all of the selected cultures at the starting times were 1.8 ± 0.1 mg, 30 μg, and 17 ± 1 μg/mg, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We discuss the nitrogen fixation, acetylene reduction, and proton reduction activities of our Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 mutants in comparison to results on the very well-studied nitrogenase from A. vinelandii. Whereas we utilized intact cyanobacterial cells for our assays, the prior studies were carried out with soluble cell extracts or purified MoFe protein under conditions of optimal or sufficient amounts of Fe protein, Na2S2O4, and MgATP. One must be cautious when comparing results obtained from in vivo and in vitro systems; for example, the cellular level of MgATP is not readily controlled. Furthermore, we cannot rule out the possibility that subtle structural differences between the A. vinelandii and Anabaena nitrogenases could affect their substrate reduction properties despite the high sequence conservation of the enzymes. Nevertheless, making such a comparison offers potential insights into the effects of the changes associated with the variant proteins.

Nitrogen-fixing capability.

The ability to fix N2 was moderately or severely impaired in nearly all of the Anabaena NifD variant strains examined. This result is consistent with expectations for the substitution of residues predicted to be proximal to the FeMo-co active site. Recent mutagenic, spectroscopic, and density functional theoretic studies have led to a prevailing view that the binding sites for N2, azide, acetylene, and hydrazine (N2H4) are located on the Fe2-Fe3-Fe6-Fe7 face of FeMo-co (7, 8, 12, 24, 29, 46). We observe that most modifications involving R284 and F388 (on the Fe2-Fe4-Fe5-Fe6 face) or Q193 and H197 (near Fe6 and Fe2, respectively) lead to substantial losses in N2 reduction activities. In contrast, the enzyme generally was more resilient to substitutions involving Y236 (near Fe1, Fe2, and Fe3) or S285 (near Fe1). Diminution of N2 reduction, as found in most of the mutants herein examined, is required if one aims to redistribute the six electrons involved in that process toward proton reduction.

Acetylene reduction.

The nine Anabaena mutants capable of N2 fixation also possess relatively high rates of acetylene reduction. In addition, several variants that were severely impaired in N2 fixation retained significant acetylene and proton reduction activities. These observations can be rationalized in terms of the Lowe and Thorneley model for nitrogenase catalysis (31, 32, 54), in which the enzyme must form a more highly reduced state (i.e., the so-called E3 or E4 state) to bind and reduce N2 than is required to reduce acetylene or protons (at the E1 or E2 state); i.e., certain mutations may lead to a less reduced cofactor.

Whereas wild-type Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 reduces acetylene only to ethylene, we noted the additional production of ethane in a number of our variants. Similarly, the wild-type MoFe protein of A. vinelandii produces only ethylene, but its Q191K, Q191E, H195N, and H195L derivatives produce 1.7 to 50% as much ethane as ethylene (17, 27, 44). The analogous Anabaena variants (Q193K, H197N, and H197L; Q193E was not examined) all produce ethane, as do many other variants. Most of these strains exhibited ethane/ethylene ratios of only ∼0.1 to 10%, but the Q193K, H197T, and H197N strains exhibited ratios of 47, 17, and 24%, respectively. The H197T and H197N mutants were of special interest because they produced ethane rapidly. In general, substitutions of Q193 and H197 appear to modulate the reduction of acetylene to ethylene and ethane.

Ethane formation from acetylene is a characteristic of vanadium-containing (9) and Fe-only (37) nitrogenases. The ethane/ethylene ratios for these Mo-independent nitrogenases range from ca. 1% to several percent regardless of the microorganisms and strains (9, 26, 35, 37, 43). Compared to these alternative nitrogenases and most of the ethane-producing variants of Mo-nitrogenase, the Q193K and H197N variants reduce acetylene to ethane very effectively. Following the lead of Fisher et al. (17), we suggest that a longer residence time of the bound ethylenic intermediate at the active site might be responsible for the increased formation of ethane.

H2 production.

The rates of H2 production by the Q193K, H197T, and R284H NifD Anabaena mutants under air approached or exceeded their rates under Ar (63 to 82%, 72 to 98%, and 99 to 120%, respectively), analogous to the in vitro results for the corresponding variants of A. vinelandii, where the O2-labile activities were similar under N2 and Ar (Q191K, H195T, and R277H, with ratios of 95, 77, and 99%, respectively) (27, 44, 48). In contrast, the cyanobacterial H197L and H197N NifD variants were much less effective at reducing protons in the presence of N2 than in its absence (44 to 52% and 19 to 23%, respectively) relative to the relevant H195L and H195N A. vinelandii enzymes (115 and 95%, respectively) (27).

The Anabaena H197Q variant produced much less H2 under air than under Ar (53%) much like the corresponding H195Q variant of A. vinelandii. The latter enzyme cannot reduce N2 effectively, but N2 can bind to the active site and inhibit proton reduction (10, 27). In addition, the binding of N2 to that altered enzyme was shown to suppress total electron flux by uncoupling MgATP hydrolysis from electron transfer, as seen most strikingly under conditions of limiting MgATP (27). N2 inhibition of H2 production most likely explains the observed behavior for several other variants studied here. Moreover, the additional negative effects of suppressed electron flux as described for the H195Q A. vinelandii enzyme might account for the significantly lower values for the rate ratios (i.e., 10, 9, and 14%) of H2 production in the presence of air versus Ar in the Q193V, Y236A, and S285N variants, respectively.

The H2 production rates of three variants (Q193H, R284H, and F388H) under air or 100% N2 (see Table S4 in the supplemental material) are similar to or slightly greater than those under Ar. This finding could indicate that N2 interacts in a positive manner with the active site during proton reduction by these variant nitrogenases. A recent study showed that N2, though not a substrate of the enzyme, increases H2 production activity by reconstituted NifDK in which FeMo-co is replaced by NifB-co containing neither Mo nor homocitrate (50). The stimulatory effect of N2 may relate to the N2-dependent pathway for HD (hydrogen deuteride) formation in the presence of D2 and N2 (20, 30). Of interest, each of these highly active Anabaena variants is predicted to place an added His close to H197. The imidazole ring of the new residue could participate in His-mediated proton transfer to the FeMo-co site (13, 22, 51). In this regard, H195 of A. vinelandii nitrogenase, equivalent to the cyanobacterial H197, hydrogen bonds to the central bridging sulfur atom (S2B) between Fe2 and Fe6 of FeMo-co and was experimentally shown to be an obligate proton donor for nitrogenous substrates (N2, azide, and hydrazine), but not for reduction of acetylene (3, 10, 27). We speculate that His residues replacing Q193, R284, and F388 in the Anabaena enzyme could hydrogen bond to neighboring residues, a water molecule, or homocitrate (in the case of Q193H) and participate in the transfer of protons to H197 in the active site or to homocitrate, which is proposed to be part of a water-filled channel potentially involved in proton transfer (13). In this regard, the Q193S variant, which also exhibits similar high H2 production rates under Ar or air, could similarly participate in proton transfer via a hydrogen-bonded chain.

Long-term accumulation of H2.

Whereas certain Anabaena variants accumulated comparable (H197F, Y236T, and R284H) or less (eight other strains) H2 than the reference strains during long-term incubations under Ar + 5% CO2, the 11 selected Anabaena NifD variants (Fig. 4) greatly exceeded the H2 accumulation of the reference strains under N2 + 5% CO2. Under these physiologically relevant conditions, the reference strains produced H2 for only 2 to 3 days and only at low rates. This result can be rationalized in terms of the diazotrophic growth capability of these strains, where the nitrogen-sufficient nutritional status leads to decreased nitrogenase activity, as previously discussed (33). The Y236T variant, the only strain examined that exhibits some diazotrophic capability, ceased producing H2 after 4 days of incubation under N2, whereas all other of the 11 variants continued to accumulate H2 over 1 week. In general, the sustained production of H2 was comparable for most mutants whether incubated under Ar or N2, although the amount of H2 accumulated by the H197F and H197Q variants was only about half as great under N2 (Fig. 4 and see Table S6 in the supplemental material).

The concentrations of H2 accumulated for all of the cultures and conditions tested leveled off by about 1 week, an observation similar to those of previous reports (28, 57). Cessation of H2 production is unlikely to be due to O2 accumulation, which we measured as 6 to 9% under Ar or N2 after 5 to 7 days (data not shown). Kumazawa and Mitsui (28) showed that H2 production could be sustained for longer periods in flasks with periodic Ar gas replacement, resulting in increased cumulative H2 production; however, the rates these researchers observed gradually decreased. Increasing levels of H2 and O2 in closed flasks results in increased pressure that was suggested to further inhibit H2 and O2 production (28). Another possibility is that H2 production is balanced by H2 uptake via the bidirectional hydrogenase (Hox) activity that was not deleted in these studies.

The R284H variant was most effective in accumulating H2 under N2 and therefore of greatest interest. The H2 accumulation by this mutant under N2 after 1 week was 87% of that observed for the two reference strains under Ar. This result highlights the potential of using this mutant as the parental strain for further mutagenesis studies in efforts to attain even greater levels of photobiological H2 production.

Concluding comments.

We demonstrate here the feasibility of engineering cyanobacterial strains for enhanced photobiological production of H2 under aerobic growth conditions. In addition to further efforts to develop strains capable of even higher levels of H2 production, many other hurdles will need to be overcome in order to develop this approach as a useful fuel source. For example, methods will need to be established for large-scale and long-term incubation of the cells under phototrophic H2-producing conditions, as well as for capturing and storing the H2 produced.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE BER Office of Science DE-FC02-07ER64494) and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from JSPS (16.9494, to H.M.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, M. B., and D. I. Arnon. 1955. Studies on nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae. I. Growth and nitrogen fixation by Anabaena cylindrica Lemm. Plant Physiol. 30:366-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barney, B. M., R. Y. Igarashi, P. C. Dos Santos, D. R. Dean, and L. C. Seefeldt. 2004. Substrate interaction at an iron-sulfur face of the FeMo-cofactor during nitrogenase catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:53621-53624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barney, B. M., M. Laryukhin, R. Y. Igarashi, H. I. Lee, P. C. Dos Santos, T. C. Yang, B. M. Hoffman, D. R. Dean, and L. C. Seefeldt. 2005. Trapping a hydrazine reduction intermediate on the nitrogenase active site. Biochemistry 44:8030-8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer, C. C., and R. Haselkorn. 1995. Vectors for determining the differential expression of genes in heterocysts and vegetative cells of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 177:3332-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman-Frank, I., P. Lundgren, and P. Falkowski. 2003. Nitrogen fixation and photosynthetic oxygen evolution in cyanobacteria. Res. Microbiol. 154:157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black, T. A., Y. Cai, and C. P. Wolk. 1993. Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 9:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dance, I. 2004. The mechanism of nitrogenase. Computed details of the site and geometry of binding of alkyne and alkene substrates and intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:11852-11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dance, I. 2007. The mechanistically significant coordination chemistry of dinitrogen at FeMo-co, the catalytic site of nitrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129:1076-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilworth, M. J., R. R. Eady, R. L. Robson, and R. W. Miller. 1987. Ethane formation from acetylene as a potential test for vanadium nitrogenase in vivo. Nature 327:167-168. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dilworth, M. J., K. Fisher, C.-H. Kim, and W. E. Newton. 1998. Effects on substrate reduction of substitution of histidine-195 by glutamine in the α-subunit of the MoFe protein of Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase. Biochemistry 37:17495-17505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dos Santos, P. C., D. R. Dean, Y. Hu, and M. W. Ribbe. 2004. Formation and insertion of the nitrogenase iron-molybdenum cofactor. Chem. Rev. 104:1135-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Santos, P. C., S. M. Mayer, B. M. Barney, L. C. Seefeldt, and D. R. Dean. 2007. Alkyne substrate interaction within the nitrogenase MoFe protein. J. Inorg. Biochem. 101:1642-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durrant, M. C. 2001. Controlled protonation of iron-molybdenum cofactor by nitrogenase: a structural and theoretical analysis. Biochem. J. 355:569-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einsle, O., F. A. Tezcan, S.-L. Andrade, B. Schmid, M. Yoshida, J. B. Howard, and D. C. Rees. 2002. Nitrogenase MoFe-protein at 1.16 Å resolution: a central ligand in the FeMo-cofactor. Science 297:1696-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elhai, J., A. Vepritskiy, A. M. Muro-Pastor, E. Flores, and C. P. Wolk. 1997. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 179:1998-2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elhai, J., and C. P. Wolk. 1988. Conjugal transfer of DNA to cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 167:747-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher, K., M. J. Dilworth, and W. E. Newton. 2000. Differential effects on N2 binding and reduction, HD formation, and azide reduction with α-195His and α-191Gln substituted MoFe proteins of Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase. Biochemistry 39:15570-15577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glazer, A. N., and K. J. Kechris. 2009. Conserved amino acid sequence features in the α subunits of MoFe, VFe, and FeFe nitrogenases. Plos One 4:e6136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golden, J. W., M. E. Mulligan, and R. Haselkorn. 1987. Different recombination site specificity of two developmentally regulated genome rearrangements. Nature 327:526-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guth, J. H., and R. H. Burris. 1983. Inhibition of nitrogenase-catalyzed NH3 formation by H2. Biochemistry 22:5111-5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howard, J. B., and D. C. Rees. 1996. Structural basis of biological nitrogen fixation. Chem. Rev. 96:2965-2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu, N. T., T. Thiel, T. H. Giddings, and C. P. Wolk. 1981. New Anabaena and Nostoc cyanophages from sewage settling ponds. Virology 114:236-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igarashi, R. Y., P. C. Dos Santos, W. G. Niehaus, I. G. Dance, D. R. Dean, and L. C. Seefeldt. 2004. Localization of a catalytic intermediate bound to the FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 279:34770-34775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneko, T., Y. Nakamura, C. P. Wolk, T. Kuritz, S. Sasamoto, A. Watanabe, M. Iriguchi, A. Ishikawa, K. Kawashima, T. Kimura, Y. Kishida, M. Korhara, M. Matsumoto, A. Matsuno, A. Muraki, N. Nakazaki, S. Shimpo, M. Sugimoto, M. Takazawa, M. Yamada, M. Yasuda, and S. Tabata. 2001. Complete genomic sequence of the filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. DNA Res. 8:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kentemich, T., G. Danneberg, B. Hundeshagen, and H. Bothe. 1988. Evidence for the occurrence of the alternative, vanadium-containing nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 51:19-24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, C. H., W. E. Newton, and D. R. Dean. 1995. Role of the MoFe α-subunit histidine-195 residue in FeMo-cofactor binding and nitrogenase catalysis. Biochemistry 34:2798-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumazawa, S., and A. Mitsui. 1994. Efficient hydrogen photoproduction by synchronously grown cells of a marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. Miami BG 043511, under high cell-density conditions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 44:854-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, H. I., R. Y. Igarashi, M. Laryukhin, P. E. Doan, P. C. Dos Santos, D. R. Dean, L. C. Seefeldt, and B. M. Hoffman. 2004. An organometallic intermediate during alkyne reduction by nitrogenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:9563-9569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, J. L., and R. H. Burris. 1983. Influence of pN2 and pD2 on HD formation by various nitrogenases. Biochemistry 22:4472-4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowe, D. J., and R. N. F. Thorneley. 1984. The mechanism of Klebsiella pneumoniae nitrogenase action: pre-steady-state kinetics of H2 formation. Biochem. J. 224:877-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowe, D. J., and R. N. F. Thorneley. 1984. The mechanism of Klebsiella pneumoniae nitrogenase action: the determination of rate constants required for the simulation of the kinetics of N2 reduction and H2 evolution. Biochem. J. 224:895-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masukawa, H., K. Inoue, and H. Sakurai. 2007. Effects of disruption of homocitrate synthase genes on Nostoc sp. strain PCC 7120 photobiological hydrogen production and nitrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7562-7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masukawa, H., M. Mochimaru, and H. Sakurai. 2002. Disruption of the uptake hydrogenase gene, but not of the bidirectional hydrogenase gene, leads to enhanced photobiological hydrogen production by the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:618-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masukawa, H., X. Zhang, E. Yamazaki, S. Iwata, K. Nakamura, M. Mochimaru, K. Inoue, and H. Sakurai. 2009. Survey of the distribution of different types of nitrogenases and hydrogenases in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. Mar. Biotechnol. 11:397-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton, W. E., and D. R. Dean. 1993. Role of the iron molybdenum cofactor polypeptide environment in Azotobacter vinelandii molybdenum nitrogenase catalysis. ACS Symp. Ser. 535:216-230. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pau, R. N., L. A. Mitchenall, and R. L. Robson. 1989. Genetic evidence for an Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase lacking molybdenum and vanadium. J. Bacteriol. 171:124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porra, R. J. 1991. Recent advances and re-assessments in chlorophyll extraction and assay procedures for terrestrial, aquatic, and marine organisms, including recalcitrant algae, p. 31-57. In H. Scheer (ed.), Chlorophylls. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 39.Prince, R. C., and H. S. Kheshgi. 2005. The photobiological production of hydrogen: potential efficiency and effectiveness as a renewable fuel. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 31:19-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubio, L. M., and P. W. Ludden. 2008. Biosynthesis of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62:93-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sage, D. R., A. C. Chillemi, and J. D. Fingeroth. 1998. A versatile prokaryotic cloning vector with six dual restriction enzyme sites in the polylinker facilitates efficient subcloning into vectors with unique cloning sites. Plasmid 40:164-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakurai, H., and H. Masukawa. 2007. Promoting R&D in photobiological hydrogen production utilizing mariculture-raised cyanobacteria. Mar. Biotechnol. 9:128-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider, K., A. Müller, U. Schramm, and W. Klipp. 1991. Demonstration of a molybdenum-independent and vanadium-independent nitrogenase in a nifHDK deletion mutant of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Eur. J. Biochem. 195:653-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott, D. J., D. R. Dean, and W. E. Newton. 1992. Nitrogenase-catalyzed ethane production and CO-sensitive hydrogen evolution from MoFe proteins having amino acid substitutions in α-subunit FeMo cofactor-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 267:20002-20010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott, D. J., H. D. May, W. E. Newton, K. E. Brigle, and D. R. Dean. 1990. Role for the nitrogenase MoFe protein α-subunit in FeMo-cofactor binding and catalysis. Nature 343:188-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seefeldt, L. C., I. G. Dance, and D. R. Dean. 2004. Substrate interactions with nitrogenase: Fe versus Mo. Biochemistry 43:1401-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seefeldt, L. C., B. M. Hoffman, and D. R. Dean. 2009. Mechanism of Mo-dependent nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:701-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen, J., D. R. Dean, and W. E. Newton. 1997. Evidence for multiple substrate-reduction sites and distinct inhibitor-binding sites from an altered Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase MoFe protein. Biochemistry 36:4884-4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simpson, F. B., and R. H. Burris. 1984. A nitrogen pressure of 50 atmospheres does not prevent evolution of hydrogen by nitrogenase. Science 224:1095-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soboh, B., E. S. Boyd, D. Zhao, J. W. Peters, and L. M. Rubio. 2010. Substrate specificity and evolutionary implications of a NifDK enzyme carrying NifB-co at its active site. FEBS Lett. 584:1487-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szilagyi, R. K., D. G. Musaev, and K. Morokuma. 2000. Theoretical studies of biological nitrogen fixation. II. Hydrogen bonded networks as possible reactant and product channels. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 506:131-146. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamagnini, P., E. Leitao, P. Oliveira, D. Ferreira, F. Pinto, D. J. Harris, T. Heidorn, and P. Lindblad. 2007. Cyanobacterial hydrogenases: diversity, regulation and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 31:692-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas, M. C., and C. A. Smith. 1987. Incompatibility of group P plasmids: genetics, evolution, and use in genetic manipulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41:77-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorneley, R. N. F., and D. J. Lowe. 1984. The mechanism of Klebsiella pneumoniae nitrogenase action: pre-steady-state kinetics of an enzyme-bound intermediate in N2 reduction and of NH3 formation. Biochem. J. 224:887-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weyman, P. D., B. Pratte, and T. Thiel. 2010. Hydrogen production in nitrogenase mutants in Anabaena variabilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 304:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolk, C. P., A. Ernst, and J. Elhai. 1994. Heterocyst metabolism and development, p. 769-823. In D. A. Bryant (ed.), The molecular biology of cyanobacteria. Springer (Kluwer Academic Publishers), Dordrecht, Netherlands.

- 57.Yoshino, F., H. Ikeda, H. Masukawa, and H. Sakurai. 2006. High photobiological hydrogen production activity of a Nostoc sp. PCC 7422 uptake hydrogenase-deficient mutant with high nitrogenase activity. Mar. Biotechnol. 9:101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.