Abstract

We performed spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from 833 systematically sampled pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) patients in urban Mumbai, India (723 patients), and adjacent rural areas in western India (110 patients). The urban cohort consisted of two groups of patients, new cases (646 patients) and first-time treatment failures (77 patients), while only new cases were recruited in the rural areas. The isolates from urban new cases showed 71% clustering, with 168 Manu1, 62 CAS, 22 Beijing, and 30 EAI-5 isolates. The isolates from first-time treatment failures were 69% clustered, with 14 Manu1, 8 CAS, 8 Beijing, and 6 EAI-5 isolates. The proportion of Beijing strains was higher in this group than in urban new cases (odds ratio [OR], 3.29; 95% confidence limit [95% CL], 1.29 to 8.14; P = 0.003). The isolates from rural new cases showed 69% clustering, with 38 Manu1, 7 CAS, and 1 EAI-5 isolate. Beijing was absent in the rural cohort. Manu1 was found to be more common in the rural cohort (OR, 0.67; 95% CL, 0.42 to 1.05; P = 0.06). In total, 71% of isolates were clustered into 58 spoligotypes with 4 predominant strains, Manu1 (26%), CAS (9%), EAI-5 (4%), and Beijing (4%), along with 246 unique spoligotypes. In the isolates from urban new cases, we found Beijing to be associated with multidrug resistance (MDR) (OR, 3.40; 95% CL, 1.20 to 9.62; P = 0.02). CAS was found to be associated with pansensitivity (OR, 1.83; 95% CL, 1.03 to 3.24; P = 0.03) and cavities as seen on chest radiographs (OR, 2.72; 95% CL, 1.34 to 5.53; P = 0.006). We recorded 239 new spoligotypes yet unreported in the global databases, suggesting that the local TB strains exhibit a high degree of diversity.

The resurgence of tuberculosis (TB) fuelled by multidrug resistance (MDR) and extensive drug resistance has caused significant concern among health care practitioners (36, 37). There have been renewed efforts to understand the biology of the pathogen alongside its epidemiology. Such data have come mostly from regions of sporadic incidence or from populations where the disease is driven by high HIV prevalence (8). Data from some of the highest-disease-burden regions, where tuberculosis has remained endemic, are scarce.

India is one such region where Mycobacterium tuberculosis has remained in equilibrium with the population, resulting in an area of tuberculosis endemicity (6, 27). Under such conditions, the strain diversity is expected to be different compared to that for epidemic or sporadic incidents, where a few specific strain types dominate (8, 23); in a setting where tuberculosis is endemic, the pathogen and the host are expected to evolve simultaneously for long durations, resulting in a set of varied strain types (6, 20, 21).

Studies from India show differential strain predominance between the southern and northern regions of the country. While the central Asian strain (CAS) is dominant in the north, East African Indian strains (EAI) are observed more frequently in the southern regions (29). Most studies from India as well as specifically from Mumbai, India, showed CAS and Manu1 as the predominant spoligotypes along with EAI as a third large strain lineage (3, 16, 18, 22, 28, 29, 30). Another study from a tertiary care center in Mumbai reported a high proportion of Beijing strains (23%) in a cohort associated with a high proportion of MDR (1). Interestingly, TbD1-positive strains of tuberculosis (such as EAI) predominate in India, whereas TbD1-negative strains of M. tuberculosis are more common in the rest of the world (11).

Although previous studies provided preliminary data from various sites in India, they did not reflect strain variability from a single cosmopolitan region. Additionally, studies from Mumbai were biased toward MDR cases (1), had small sample sizes (16), or were derived from a cohort of chronic (re-treated) TB cases accessing tertiary care hospitals (22).

Epidemiological studies of M. tuberculosis have been facilitated by a variety of genotyping tools. IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) remains the gold standard due to its high level of discrimination (15) but is time-consuming and less suitable in populations with low copy numbers (7). Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit-variable-number tandem-repeat (MIRU-VNTR) typing (10, 19, 31) is a high-throughput and discriminatory method, but the best combination of MIRU loci is yet to be achieved, and combinations may differ between populations (33). We used spoligotyping as a primary fingerprint method, due to its relatively high throughput nature. Spoligotyping has a lower discriminatory power than MIRU-VNTR typing, making it less suitable for determining strain transmission. However, spoligotyping served as a useful primary fingerprinting tool allowing comparisons of strain types from strains around the world through updated global databases (5, 17, 35).

In this study, we describe the distribution of strain genotypes from a systematic collection of strains from urban Mumbai and two neighboring rural areas. Mumbai is a location where a confluence of people from all parts of the country live in poor, congested neighborhoods with high population densities, up to 64,168 people per square kilometer in one of the city wards as per the 2001 census (26). These conditions, coupled with a high proportion of MDR cases in the region (2, 9), were cause for concern and underlined the need for more information on local circulating strains. We wished to determine the distribution of strains among newly diagnosed TB patients in the region to extend previous observations (16, 22).

This study describes the spoligotypes present in the cohort and the extent of their clustering. We further analyzed the association of spoligotypes with other parameters, namely, age, gender, geographical origin of the host, radiology, and multidrug resistance, to obtain deeper insights into strain behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location of study.

The Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) in Mumbai is implemented in individual wards of the city. Since this study was part of a larger epidemiological project assessing transmission of MDR TB in a setting of TB endemicity, 4 centrally located wards (F/N, G/N, H/E, and K/E) characterized by a high sputum-positive case load, with moderately suboptimal cure rates ranging between 78 and 81%, were selected (RNTCP quarterly reports 2001; can be sourced from dtomhbmc@rntcp.org). As far as could be ascertained, there was no apparent deviation in the RNTCP functioning in these wards compared to that in the other wards in Mumbai. A significant proportion of the resident population of these 4 selected wards belonged to the middle or lower socioeconomic class and resided in informal housing in slums. Cumulatively, the 4 wards covered 38 DOTS (directly observed therapy short course) centers, with a population of 3 million.

In addition, we sampled patients from rural TB units (located 250 and 280 km from Mumbai), covering a population of 860,000. This facilitated studying spoligotypes from a rural cohort which, as opposed to Mumbai, had a homogeneous population comprising an indigenous community with little or no migration from other parts of India. Unlike the rural cohort, that from the Mumbai region included a large migrant population from other parts of India (37%) (26). We could thus compare strain diversities in homogenous (rural) and cosmopolitan (Mumbai, urban) cohorts in the same geographical location. Additionally, there exists a movement of people from these rural areas to Mumbai, in the form of unskilled industrial labor, which provided the opportunity to study the overlap of TB strains between the two locations.

Case definition.

Sputum-positive new cases of TB were broadly classified into two groups: (i) new cases sampled at onset of CAT1 therapy, a regimen of 2(isoniazid [H]-ethambutol [E]-rifampin [R]-pyrazinamide [Z])3 + 4(H-R)3, comprising 2 months of H-E-R-Z thrice weekly followed by 4 months of H-R thrice weekly), and (ii) first-time treatment failures, or new cases who remained sputum smear positive at the fifth month after commencement of CAT1 therapy. All rural patients were new cases sampled at onset of therapy. Patients were recruited from April 2004 to September 2007 at RNTCP DOTS centers.

Inclusion criteria for patients were (i) smear positivity, (ii) age from 15 to 70 years, (iii) residency in Mumbai for at least 3 years immediately prior to diagnosis, and (iv) residence in the same area as the health posts where treatment was sought.

Sputum-negative cases were excluded, as we were unable to perform sputum culture on all patients, due to study constraints. Patients who had not resided in the area for at least 3 years were excluded, as we were interested primarily in strains causing disease in the resident population of Mumbai. Since the study aimed to identify strains circulating in the region during the study period, previously treated patients were excluded to eliminate relapse cases, which are less likely to relate to a current transmission event. Patients with a history of TB or antituberculosis therapy were determined through interview and scrutiny of district TB registers and patients defaulting during therapy (in the case of first-time treatment failures). As far as could be ascertained, the first-time treatment failures had not received any antituberculosis therapy prior to the current episode. Patients were recruited after informed consent and referred for HIV counseling and testing.

Clearance for this study was obtained from the Foundation for Medical Research (FMR) institutional ethics committee (20.07.2001/01).

Patient investigations.

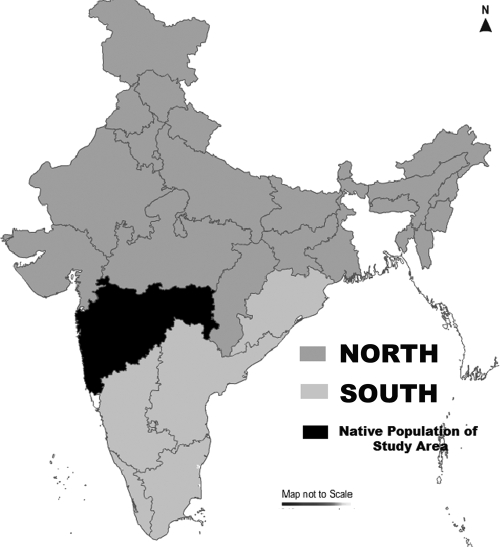

Patient demographic details, including age, gender, and geographical origin, were recorded. Since many patients were found to be migrants from other parts of the country, they were analyzed based on 3 groups: south India, north India, and Maharashtra (considered the native population) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Geographical demarcations of India. (The map was created using MapXL Maps of India, v.6 [Compare Infobase Limited].)

All patients recruited were subjected to radiological examination and were binomially classified into groups by presence or absence of cavities.

Sample processing and culture.

Sputum samples (one per patient) were collected in cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC)-NaCl vials as previously described (9). These samples were then concentrated by Petroff's method (4). The concentrated samples were inoculated onto solid Lowenstein-Jensen slants (Hi-Media, India) and incubated at 37°C until growth was observed.

DNA extraction.

A loopful of culture was used to extract DNA by a standard cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) mycobacterial DNA extraction procedure, followed by phenol chloroform purification (13, 14).

Spoligotyping.

Spoligotyping was conducted as previously described (12). Clusters were defined as at least 2 isolates with identical spoligotypes.

A random selection of samples (DNA extracted from 80 isolates in Tris-EDTA [TE] in freezer packs) was sent to the Institute of Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town (IIDMM, UCT), for single-blinded quality control.

Drug susceptibility testing.

Drug susceptibility testing for the four first-line drugs rifampin (R), isoniazid (H), ethambutol (E), and pyrazinamide (Z) was performed by the radiorespirometric Buddemeyer technique (a manual modification of the BACTEC 460 technique) (9). Strains resistant to at least H and R were classified as multidrug resistant (MDR). Resistance to H, R, and an additional first-line drug was represented as MDR+. Ten percent of the isolates were sent to the Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control (supranational reference laboratory), Stockholm, for external quality assurance by the BACTEC method. Kappa scores showed good agreement for H (0.76) and R (0.77) (9).

Statistical analysis.

Multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) was performed with the spoligotype as the dependent variable and MDR, susceptibility, HIV status, and cavitation in the new cases (first-time treatment failures excluded) as covariates. A chi-square test was performed to find associations between spoligotype and (i) patient subgroup (first-time treatment failures, urban new cases, and rural cases) or (ii) region of origin.

All patient data were entered and maintained using SPSS v10.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Analyses were done with SPSS and Microsoft Office Excel 1997 (Microsoft Corporation). Spoligotype comparison to SpoldB3 (35) (http://cgi2.cs.rpi.edu/∼bennek/SPOTCLUST.html) and SpoldB4 (17) (http://www.pasteur-guadeloupe.fr:8081/SITVITDemo/) was done using tools available on the respective websites.

RESULTS

Patient selection. (i) Urban.

We screened 1,136/2,184 (52%) new cases who presented to the RNTCP for diagnosis between April 2004 and September 2007. We included 646 new cases in the urban cohort from the 1,136 screened, based on our inclusion criteria. The 490 patients excluded from the study consisted of 135 (28%) with prior antituberculosis treatment, 222 (45%) who had taken more than 5 doses of antituberculosis therapy before sampling, and 24 (5%) who resided outside the study area. One hundred nine patients (22%) refused to participate in the study. During the same period, we screened 318 treatment failures, of which 77 were included. The 241 excluded patients consisted of 86 (36%) with prior antituberculosis therapy, 114 (47%) with an interruption in treatment of more than 2 weeks, and 14 (6%) who resided outside the study area. Twenty-seven patients (11%) refused to participate in the study.

(ii) Rural.

The rural cohort consisted of 110 patients out of 262 screened (42%).Thus, a total of 833 isolates from urban (n = 723) and rural (n = 110) patients were spoligotyped (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4).

TABLE 1.

Patient distribution in the cohort across the different locations and patient types

| Patient study group and cohort | Ward or TB unit | Spoligotype clustering |

No. of isolates of major spoligotype |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of clustered isolates | No. of unique isolates | Total | Manu1 | CAS | Beijing | EAI-5 | ||

| Treatment failures | ||||||||

| Mumbai (urban) | F/N | 20 (67) | 10 | 30 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| G/N | 4 (50) | 4 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| H/E | 13 (65) | 7 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| K/E | 16 (84) | 3 | 19 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | 53 (69) | 24 | 77 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 6 | |

| New cases | ||||||||

| Mumbai (urban) | F/N | 194 (72) | 74 | 268 | 64 | 28 | 14 | 14 |

| G/N | 78 (70) | 34 | 112 | 37 | 8 | 1 | 4 | |

| H/E | 86 (74) | 31 | 117 | 32 | 9 | 1 | 3 | |

| K/E | 100 (67) | 49 | 149 | 35 | 17 | 6 | 9 | |

| Total | 458 (71) | 188 | 646 | 168 | 62 | 22 | 30 | |

| Rural | Narayangaon | 46 (70) | 20 | 66 | 24 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Bhor | 30 (68) | 14 | 44 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 76 (69) | 34 | 110 | 38 | 7 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 587 (71) | 246 | 833 | 220 | 77 | 30 | 37 | |

TABLE 2.

Distribution of clustered strains in the total cohort

| No. of isolates within cluster | No. of clusters with this characteristic | No. of strains with this characteristic/total no. of isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ≥10 | 8 | 421/833 (51) |

| <10 | 50 | 166/833 (20) |

| <5 | 41 | 108/833 (13) |

| 2 | 23 | 46/833 (0.06) |

TABLE 3.

All spoligotypes in different patient types

| Cluster or unique spoligotype | No. of isolates in patient study group |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban treatment failures | Urban new cases | Rural new cases | ||

| C1 | 8 | 62 | 7 | 77 |

| C2 | 8 | 22 | 30 | |

| C3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| C4 | 8 | 2 | 10 | |

| C5 | 8 | 8 | ||

| C6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| C7 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 11 |

| C8 | 5 | 5 | ||

| C9 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C10 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| C11 | 1 | 17 | 18 | |

| C12 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 18 |

| C13 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C14 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C15 | 14 | 168 | 38 | 220 |

| C16 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| C17 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| C18 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| C19 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C20 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C21 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C22 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| C23 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C24 | 6 | 30 | 1 | 37 |

| C25 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C26 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C27 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C28 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C29 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C30 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C31 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| C32 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| C33 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C34 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| C35 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C36 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C37 | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| C38 | 4 | 4 | ||

| C39 | 4 | 4 | ||

| C40 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| C41 | 4 | 4 | ||

| C42 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C43 | 3 | 3 | ||

| C44 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C45 | 4 | 4 | ||

| C46 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C47 | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| C48 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C49 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| C50 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| C51 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| C52 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| C53 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| C54 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C55 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| C56 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| C57 | 2 | 2 | ||

| C58 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Unique spoligotype | 24 | 188 | 34 | 246 |

| Total | 77 | 646 | 110 | 833 |

TABLE 4.

Distribution of major spoligotypes based on geographical origin of patient

| Spoligotype category and parameter | Result for patients with GOa of: |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maharashtra | Northern India | Eastern India | Western India | Southern India | ||

| Manu1 | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 130 | 59 | 5 | 11 | 15 | 220 |

| % within cluster | 59 | 27 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 100 |

| % within GO | 28 | 25 | 33 | 28 | 21 | 26 |

| % of total | 16 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 26 |

| CAS | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 32 | 31 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 77 |

| % within cluster | 42 | 40 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 100 |

| % within GO | 7 | 13 | 0 | 18 | 10 | 9 |

| % of total | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| EAI-5 | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 25 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 37 |

| % within cluster | 68 | 22 | 0 | 3 | 8 | ∼100 |

| % within GO | 5 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| % of total | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Beijing | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 12 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 30 |

| % within cluster | 40 | 43 | 3 | 3 | 10 | ∼100 |

| % within GO | 3 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| % of total | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Other clusters | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 117 | 66 | 4 | 9 | 27 | 223 |

| % within cluster | 53 | 30 | 2 | 4 | 12 | ∼100 |

| % within GO | 25 | 28 | 27 | 23 | 37 | 27 |

| % of total | 14 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 27 |

| Unique spoligotype | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 153 | 60 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 246 |

| % within cluster | 62 | 24 | 2 | 4 | 7 | ∼100 |

| % within GO | 33 | 25 | 33 | 26 | 25 | 30 |

| % of total | 18 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 30 |

| Total | ||||||

| No. of isolates | 469 | 237 | 15 | 39 | 73 | 833 |

| % within cluster | 56 | 29 | 2 | 5 | 9 | ∼100 |

| % within GO | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| % of total | 56 | 29 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 100 |

GO, geographical origin.

Spoligotyping.

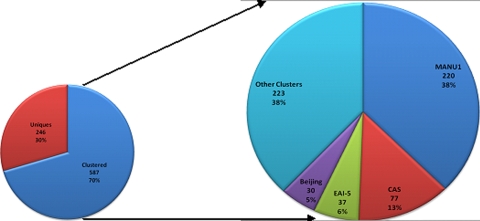

The four major clusters, designated C1, C2, C15, and C24, contained 77, 30, 220, and 37 isolates, respectively (Fig. 2). The clusters were labeled C1 through C58 sequentially as they were formed during the study period.

FIG. 2.

Spoligotype proportions.

When all of the spoligotypes were compared to the international spoligotype database SpoldB4 (5), the shared types (ST) and labels were C1, CAS1_Delhi (ST26); C2, Beijing (ST1); C15, Manu1 (ST100); and C24, EAI-5 (ST236). Therefore, Manu1 emerged as the largest strain type, infecting 26.4% of the urban and rural cohorts (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

New cases (urban).

The urban cohort consisted of 646 isolates from new cases sampled at onset of therapy. Seventy-one percent (458/646) of these were found to be clustered into 56 spoligotypes (Table 3). Manu1 was the largest cluster, with 168 (26%) isolates (Table 1). We found 62 (9.5%) CAS isolates, 22 (3.4%) Beijing isolates, and 30 (4.6%) EAI-5 isolates in the cohort (Table 1). Although this was the largest subgroup of patients, it did not contain 2 spoligotypes (C9 and C6) (Table 3).

First-time treatment failures.

Seventy-seven treatment failures sampled at the end of 5 months of treatment yielded 24 unique spoligotypes and a clustering of 69% (Tables 1 and 3).

The 53 clustered strains were divided into 18 spoligotypes. Manu1 was the largest cluster, with 14 isolates (18%), followed by CAS and Beijing, with 8 isolates each (10%). EAI-5 was the fourth largest cluster, with 6 isolates (8%) (Table 1). The proportion of Beijing isolates in the treatment failures was found to be significantly higher than that in the urban new cases (odds ratio [OR], 3.29; 95% confidence limit [95% CL], 1.29 to 8.14; P = 0.003) (Table 5). This subgroup consisted of both the isolates that formed the C9 cluster not found in new cases and 1 isolate of the C6 cluster (Table 3).

TABLE 5.

Significant associations between spoligotype and biological parameter

| Parameter | No. of isolates of spoligotypec |

OR | 95% CL | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manu1 | CAS | Beijing | EAI-5 | ||||

| Rural cohorta | 38* | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1.57 | 0.41-1.00 | 0.04 |

| Treatment failuresb | 14 | 8 | 8* | 6 | 3.29 | 1.29-8.14 | 0.003 |

| % of isolates MDR within a cluster (urban new cases)b | 20 | 17 | 41* | 27 | 3.40 | 1.20-9.62 | 0.02 |

| % of isolates pansensitive within a cluster (urban new cases)b | 33 | 53* | 41 | 47 | 1.83 | 1.03-3.24 | 0.03 |

| % of patients with lung cavities within a clustera | 54 | 83* | 62 | 56 | 2.72 | 1.34-5.53 | 0.006 |

| % of patients from north India within a clusterb | 27 | 40* | 43 | 22 | 1.8 | 1.08-2.99 | 0.02 |

Chi-square test.

Binary logistic regression.

*, proportion is significantly high compared to those of other spoligotypes.

New cases (rural).

The 110 isolates in the rural cohort were divided into 21 clusters and 34 unique spoligotypes. The 21 clusters comprised 69% (76/110) of the rural isolates and were also seen in the urban cohort. Manu1 was the largest cluster, with 38 (34.5%) of the isolates, followed by 7 CAS isolates (6.3%) and 1 EAI-5 isolate. Additionally, we found no Beijing strains among the 110 isolates (Table 1).

In total, we found 833 spoligotypes, of which 246 were unique, while the remaining were distributed across 58 spoligotype clusters. A total of 70.5% of strains were clustered. The proportions of clustered strains were similar in the urban and rural cohorts (70.6% and 69.1%, respectively).

Although 71% of the isolates were present in clusters, a large number of these clusters had few isolates in them. Of the 587 clustered strains, 421 (72%) were in clusters with greater than 10 isolates in them. Fifty-one percent of the isolates formed only 8 clusters. Twenty-three clusters had only 2 isolates in them (Table 2).

Additionally, we have reported 239/304 (79%) new spoligotypes (22 clustered and 217 unique) which may be added to existing databases to provide a better representation of strains from a high-burden region (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

A concordance of 97% was found between spoligotyping results from our laboratory and IIDMM, UCT.

Spoligotype associations (new cases). (i) Multidrug resistance.

We did not observe any significant difference in the clustering percentages between treatment failures and new cases (68.8% and 70.6%, respectively) (data not shown) or across different drug susceptibility profiles (sensitive, 68%; MDR, 68%; single-drug resistant, 75%; other resistance, 73%) (data not shown).

Analyses of associations between spoligotype and drug resistance showed a significantly higher proportion of Beijing strains than other strain types among the MDR isolates (OR, 3.40; 95% CL, 1.20 to 9.62; P = 0.02). We also found a significantly higher proportion of CAS strains than other strain types in the pansensitive group (OR, 1.83; 95% CL, 1.03 to 3.24; P = 0.03) (Table 5). Beijing strains were also found to be significantly associated with treatment failures (OR, 3.29; 95% CL, 1.29 to 8.14; P = 0.003), which was independent of MDR, as found by multivariate analysis.

(ii) Extent of radiographic disease.

We further observed that infection with CAS was significantly associated with the presence of cavities on chest radiographs, compared to results for the rest of the cohort (OR, 2.72; 95% CL, 1.34 to 5.53; P = 0.006) (Table 5).

(iii) Geographical origin of patient.

On analyzing the spoligotypes for association with specific host background (Table 4), we found a significantly high number of CAS strains in isolates from people originating from the northern regions of India compared to the numbers in the rest of the cohort (OR, 1.84; 95% CL, 1.08 to 2.99; P = 0.02) (Table 5) and in the indigenous population (OR, 2.05; 95% CL, 1.18 to 3.56; P = 0.006). We also found a higher proportion of Manu1 strains in the rural population than in the urban new cases (OR, 0.67; 95% CL, 0.42 to 1.05; P = 0.06) (data not shown) and a significantly higher proportion than in the urban cohort (OR, 1.57; 95% CL, 0.41 to 1.00; P = 0.04).

No significant associations between spoligotype and age or gender were seen.

(iv) HIV status.

Of the 833 patients, HIV status was available for 722 individuals. Of these, 32 (4.5%) had tested positive. No association between HIV status and spoligotype was found.

DISCUSSION

This to the best of our knowledge is the largest community-based molecular fingerprinting study of M. tuberculosis with a well-characterized cohort of new pulmonary tuberculosis cases from India (1, 2, 3, 11, 16, 22, 28, 29, 30). We included only sputum-positive patients to enhance the possibility of typing actively transmitting strains. Although the exclusion of sputum-negative cases could potentially have introduced a bias in the strain composition, we were unable to perform sputum culture on all patients due to study constraints. We demonstrated a predominance of Manu1 along with a high proportion of CAS strains in our cohort, versus the predominance of Harlem and LAM strains in Africa and South America, Beijing and T strains in the Americas, the Beijing strain in East Asia, and the T strain in Europe (5, 32). Concurrent with earlier reports from India (28) and specifically Mumbai (16), we found a low proportion of the Beijing strain in our cohort. This is different from the 23% proportion of Beijing reported by a tertiary care center in Mumbai catering to a more affluent population (1). The high incidence of Beijing in that study may be attributed to the selection bias toward MDR TB patients and also to a significantly higher proportion of migrant Tibetan populations accessing the tertiary care center (personal communication from Camilla Rodriguez, Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai). Additionally, we found a high strain diversity, with a large number of small clusters, as well as a significant proportion (79%) of strains hitherto unreported in the global databases.

In comparing the spoligotype proportions reported from other studies in India (3, 28, 29) to our observations, we found that our cohort had a higher proportion of Manu1 (26% versus 7%), a lower proportion of EAI-5 (4% versus 20 to 45%), and a comparable proportion of CAS (9% versus 5 to 43%). These results may indicate that different strains predominate in different regions of the country.

The low proportion of Beijing in the urban cohort and its absence in the rural cohort suggest that this strain remains uncommon among the general population in this part of India.

The independent association of Beijing with MDR and treatment failure cases (as brought out by multivariate analysis) supports earlier findings (23, 25). In contrast, CAS was found to be associated with drug sensitivity and with cavitation. These observations suggest that modern strains like Beijing may have evolved more under drug pressures, leading to an accumulation of drug-resistant mutations, while ancestral strains, like CAS, may have evolved to cause cavitation and hence increase the opportunity for transmission (24, 34).

Conclusion.

Results from this study raise issues that may be typical for a cosmopolitan population in which TB is endemic.

The constant exposure of the host to the pathogen (as in a setting of disease endemicity) has probably resulted in the high strain diversity. In contrast to the variability, the predominance of Manu1 (highest proportion ever reported) is indicative of a persistence of local strains. Interestingly, the high proportion of Manu1 in the urban cohort was significantly lower than that in the more homogenous rural cohort. Concurrently, Beijing (considered to be an imported strain), displaying a low proportion in the urban cohort, was absent in the more homogeneous rural cohort.

The increasing predominance of one strain (Manu1) along with the decreasing penetrance of another (Beijing) as the homogeneity of the population increased from urban to rural probably reflects the effect of migration. This is further substantiated by the significant presence of strains predominant elsewhere in India (CAS and EAI-5) in the cosmopolitan urban cohort.

The preliminary inferences from this study plead for a more extensive analysis of the data to study the variability of M. tuberculosis strains and their transmission dynamics.

The study represents a first step toward amalgamating clinical, genetic, and social factors that are intrinsic to the evolution of the pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by The Wellcome Trust (CRIG grant 073138/Z/03/A).

We thank our clinical consultant, Yatin Dholakia, our statistical consultant, K. Ramchandran, and our field operation consultant, Sheela Rangan, for their expert advice. We thank our field workers who collected the samples and also interviewed all of the patients. We thank the late N. H. Antia, the founder and director of the Foundation for Medical Research, who paved the way for doing meaningful research combining science and public health. We also extend our sincerest thanks to all of the patients, without whose support this project would never have been possible.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 August 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida, D., C. Rodrigues, T. F. Ashavaid, A. Lalvani, Z. F. Udwadia, and A. Mehta. 2005. High incidence of the Beijing genotype among multidrug-resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a tertiary care center in Mumbai, India. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:881-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida, D., C. Rodrigues, Z. F. Udwadia, A. Lalvani, G. D. Gothi, P. Mehta, and A. Mehta. 2003. Incidence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in urban and rural India and implications for prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:e152-e154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora, J., U. B. Singh, N. Suresh, T. Rana, C. Porwal, A. Kaushik, and J. N. Pande. 2009. Characterization of predominant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from different subpopulations of India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 9:832-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker, J. F., and R. E. Silverton. 1978. Introduction to medical laboratory technology, 5th ed. Butterworths, London, United Kingdom.

- 5.Brudey, K., J. R. Driscoll, L. Rigouts, W. M. Prodinger, A. Gori, S. A. Al-Hajoj, C. Allix, L. Aristimuno, J. Arora, V. Baumanis, L. Binder, P. Cafrune, A. Cataldi, S. Cheong, R. Diel, C. Ellermeier, J. T. Evans, M. Fauville-Dufaux, S. Ferdinand, D. Garcia de Viedma, C. Garzelli, L. Gazzola, H. M. Gomes, M. C. Guttierez, P. M. Hawkey, P. D. van Helden, G. V. Kadival, B. N. Kreiswirth, K. Kremer, M. Kubin, S. P. Kulkarni, B. Liens, T. Lillebaek, M. L. Ho, C. Martin, I. Mokrousov, O. Narvskaia, Y. F. Ngeow, L. Naumann, S. Niemann, I. Parwati, Z. Rahim, V. Rasolofo-Razanamparany, T. Rasolonavalona, M. L. Rossetti, S. Rusch-Gerdes, A. Sajduda, S. Samper, I. G. Shemyakin, U. B. Singh, A. Somoskovi, R. A. Skuce, D. van Soolingen, E. M. Streicher, P. N. Suffys, E. Tortoli, T. Tracevska, V. Vincent, T. C. Victor, R. M. Warren, S. F. Yap, K. Zaman, F. Portaels, N. Rastogi, and C. Sola. 2006. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex genetic diversity: mining the fourth international spoligotyping database (SpolDB4) for classification, population genetics and epidemiology. BMC Microbiol. 6:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman, P. G., B. D. Perry, and M. E. Woolhouse. 2001. Endemic stability—a veterinary idea applied to human public health. Lancet 357:1284-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronin, W. A., J. E. Golub, L. S. Magder, N. G. Baruch, M. J. Lathan, L. N. Mukasa, N. Hooper, J. H. Razeq, D. Mulcahy, W. H. Benjamin, and W. R. Bishai. 2001. Epidemiologic usefulness of spoligotyping for secondary typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with low copy numbers of IS6110. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3709-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day, C., and A. Gray. 2006. Health and related indicators, p. 369-506. In P. Ijumba and A. Padarath (ed.), South African health review 2006. Health Systems Trust, Durban, South Africa.

- 9.D'Souza, D. T., N. F. Mistry, T. S. Vira, Y. Dholakia, S. Hoffner, G. Pasvol, M. Nicol, and R. J. Wilkinson. 2009. High levels of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in new and treatment-failure patients from the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme in an urban metropolis (Mumbai) in Western India. BMC Public Health 9:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frothingham, R., and W. A. Meeker-O'Connell. 1998. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology 144:1189-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez, M. C., N. Ahmed, E. Willery, S. Narayanan, S. E. Hasnain, D. S. Chauhan, V. M. Katoch, V. Vincent, C. Locht, and P. Supply. 2006. Predominance of ancestral lineages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1367-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamerbeek, J., L. Schouls, A. Kolk, M. van Agterveld, D. van Soolingen, S. Kuijper, A. Bunschoten, H. Molhuizen, R. Shaw, M. Goyal, and J. van Embden. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:907-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolk, A. H., A. R. Schuitema, S. Kuijper, J. van Leeuwen, P. W. Hermans, J. D. van Embden, and R. A. Hartskeerl. 1992. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples by using polymerase chain reaction and a nonradioactive detection system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2567-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kox, L. F., D. Rhienthong, A. M. Miranda, N. Udomsantisuk, K. Ellis, J. van Leeuwen, S. van Heusden, S. Kuijper, and A. H. Kolk. 1994. A more reliable PCR for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:672-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kremer, K., D. van Soolingen, R. Frothingham, W. H. Haas, P. W. Hermans, C. Martin, P. Palittapongarnpim, B. B. Plikaytis, L. W. Riley, M. A. Yakrus, J. M. Musser, and J. D. van Embden. 1999. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2607-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni, S., C. Sola, I. Filliol, N. Rastogi, and G. Kadival. 2005. Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Mumbai, India. Res. Microbiol. 156:588-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liens, B., C. Sola, K. Brudey, N. Rastogi, et al. 2005. A web-site for a global database of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex spoligotypes and MIRU-VNTRs (SITVIT), abstr. O1. 26th Annu. Congr. Eur. Soc. Mycobacteriol., Istanbul, Turkey.

- 18.Mathuria, J. P., P. Sharma, P. Prakash, J. K. Samaria, V. M. Katoch, and S. Anupurba. 2008. Role of spoligotyping and IS6110-RFLP in assessing genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazars, E., S. Lesjean, A. L. Banuls, M. Gilbert, V. Vincent, B. Gicquel, M. Tibayrenc, C. Locht, and P. Supply. 2001. High-resolution minisatellite-based typing as a portable approach to global analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis molecular epidemiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:1901-1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGrath, J. W. 1988. Social networks of disease spread in the lower Illinois valley: a simulation approach. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 77:483-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyers, L. A., B. R. Levin, A. R. Richardson, and I. Stojiljkovic. 2003. Epidemiology, hypermutation, within-host evolution and the virulence of Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270:1667-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mistry, N. F., A. M. Iyer, D. T. D'Souza, G. M. Taylor, D. B. Young, and N. H. Antia. 2002. Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from multiple-drug-resistant tuberculosis patients from Bombay, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2677-2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mokrousov, I., W. W. Jiao, G. Z. Sun, J. W. Liu, V. Valcheva, M. Li, O. Narvskaya, and A. D. Shen. 2006. Evolution of drug resistance in different sublineages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2820-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton, S. M., R. J. Smith, K. A. Wilkinson, M. P. Nicol, N. J. Garton, K. J. Staples, G. R. Stewart, J. R. Wain, A. R. Martineau, S. Fandrich, T. Smallie, B. Foxwell, A. Al-Obaidi, J. Shafi, K. Rajakumar, B. Kampmann, P. W. Andrew, L. Ziegler-Heitbrock, M. R. Barer, and R. J. Wilkinson. 2006. A deletion defining a common Asian lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis associates with immune subversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15594-15598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parwati, I., B. Alisjahbana, L. Apriani, R. D. Soetikno, T. H. Ottenhoff, A. G. van der Zanden, J. van der Meer, D. van Soolingen, and R. van Crevel. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype is an independent risk factor for tuberculosis treatment failure in Indonesia. J. Infect. Dis. 201:553-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 2001. Census of India. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, New Delhi, India. http://www.censusindia.net/.

- 27.Rothschild, B. M., and R. Laub. 2006. Hyperdisease in the late Pleistocene: validation of an early 20th century hypothesis. Naturwissenschaften 93:557-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma, P., D. S. Chauhan, P. Upadhyay, J. Faujdar, M. Lavania, S. Sachan, K. Katoch, and V. M. Katoch. 2008. Molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a rural area of Kanpur by spoligotyping and mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs) typing. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8:621-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh, U. B., J. Arora, N. Suresh, H. Pant, T. Rana, C. Sola, N. Rastogi, and J. N. Pande. 2007. Genetic biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 7:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh, U. B., N. Suresh, N. V. Bhanu, J. Arora, H. Pant, S. Sinha, R. C. Aggarwal, S. Singh, J. N. Pande, C. Sola, N. Rastogi, and P. Seth. 2004. Predominant tuberculosis spoligotypes, Delhi, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1138-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Supply, P., S. Lesjean, E. Savine, K. Kremer, D. van Soolingen, and C. Locht. 2001. Automated high-throughput genotyping for study of global epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3563-3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsolaki, A. G., S. Gagneux, A. S. Pym, Y. O. Goguet de la Salmoniere, B. N. Kreiswirth, D. Van Soolingen, and P. M. Small. 2005. Genomic deletions classify the Beijing/W strains as a distinct genetic lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3185-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valcheva, V., I. Mokrousov, O. Narvskaya, N. Rastogi, and N. Markova. 2008. Utility of new 24-locus variable-number tandem-repeat typing for discriminating Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates collected in Bulgaria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3005-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Crevel, R., E. Karyadi, F. Preyers, M. Leenders, B. J. Kullberg, R. H. Nelwan, and J. W. van der Meer. 2000. Increased production of interleukin 4 by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from patients with tuberculosis is related to the presence of pulmonary cavities. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1194-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitol, I., J. Driscoll, B. Kreiswirth, N. Kurepina, and K. P. Bennett. 2006. Identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strain families using spoligotypes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 6:491-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. 2008. Global tuberculosis control—surveillance, planning, financing. WHO/HTM/TB/2008.393. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 37.World Health Organization. 2000. Global project on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. Report no. 2: prevalence and trends. WHO/CDS/TB/2000.278. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.