Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus originated due to triple reassortment of human, avian, and swine viruses (6). The pandemic epicenter was in Mexico, where the first human case was reported on 12 April 2009 (1). Thereafter, 16,813 pandemic H1N1 influenza A-related deaths have been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) by 213 countries between April 2009 and March 2010 (8). From a laboratory perspective, detection and discrimination of pandemic H1N1 from seasonal and swine H1N1 is crucial for accurate diagnosis and disease surveillance.

We previously described a laboratory-developed influenza A virus real-time reverse transcription-PCR (rRT-PCR) assay (Mayo FLU A) for simultaneous identification and subtype discrimination of influenza A virus RNA using melting temperature (Tm) analysis (3, 9). As discussed in the paper by Dhiman et al., loss of subtype discriminatory ability occurred in just 3 months of testing for the pandemic virus, due to multiple point mutations in the targeted 242-base region of the highly conserved matrix (M) gene as determined on a subset of 12 isolates (3). In the current paper, we have extended our analysis to a significantly larger data set to conduct mutational and amino acid analysis and characterize the genetic changes in the M gene of the pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus.

Between 1 May 2009 and 31 December 2009, we detected 1,731 influenza A virus clinical isolates out of 9,614 isolates tested (18% positivity rate) using the Mayo FLU A assay; the majority were identified as the pandemic H1N1 subtype based on predefined Tm criteria (50.5°C to 53.2°C). However, between 14 August and 31 December 2009, 48 clinical samples were identified with Tms outside the validated range for pandemic H1N1 (48 of 1,579 isolates [3.0%] during this period), with an overall lower mean Tm of 46.71 ± 1.73°C. Only one specimen, from Ann Arbor, MI, had a higher Tm of 55.5°C, which is unexpected, given that mutations typically cause a decrease rather than an increase in Tm. The significance of this result is unknown, as we did not have additional specimens from that geographical area to confirm if this result was an actual trend or an outlier.

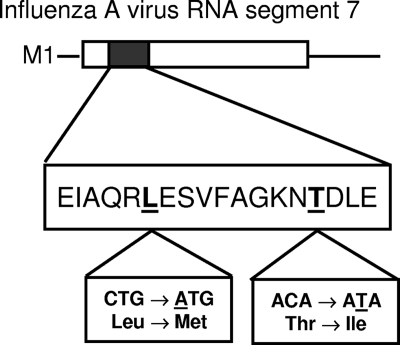

All atypical Tm samples were confirmed as pandemic H1N1 using the CDC swine flu assay. We sequenced the 242-base oligonucleotide amplicon in 37 isolates to identify the mutations responsible for the atypical Tms. Mutational analysis revealed multiple point mutations in the 57-bp region detected by the probes compared to the original pandemic H1N1 gene sequence published by the WHO on 28 April 2009 (2) (Table 1). Six of these were silent mutations, resulting in nucleotide changes GAG→GAA, ATC→ATT, GCG→GCA, AGA→AGG, CTG→TTG, and AAC→AAT at amino acid positions 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, and 36, respectively, compared to the original pandemic H1N1 gene sequence. Of interest, two additional nonsynonymous mutations, CTG→ATG and ACA→ATA, resulted in downstream changes in amino acid sequence at positions Leu28Met and Thr37Ile, respectively (Fig. 1). We also observed geographic clustering among the mutations in these analyses (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sequence alignment in the discriminatory region of the amplified matrix gene from 37 clinical isolates with atypical Tms using the Mayo FLU A assay

| Sequence source or patient no. | Mayo FLU A Tm (°C) | Statea | Sequence of discriminatory region of M gened |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein probe | CTb | Red 640 probe | |||

| WHO sequence | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC | ||

| 1 | 55.5 | MI | CGAAATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 2 | 47.8 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 3c | 47.4 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 4c | 47.4 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 5c | 47.5 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 6c | 47.6 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 7 | 47.9 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 8 | 47.6 | PA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 9c | 41.6 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATATAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 10 | 41.8 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATATAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 11c | 41.9 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATATAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 12 | 47.6 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 13 | 47.6 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 14 | 47.7 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 15 | 47.5 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 16 | 48.0 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 17 | 47.6 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 18 | 47.6 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 19 | 47.7 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 20 | 46.1 | OH | CGAGATCGCACAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 21 | 45.6 | OH | CGAGATCGCACAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 22 | 45.4 | OH | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGATTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 23 | 45.1 | MN | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGAATGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 24 | 45.1 | MN | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGAATGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 25 | 46.2 | MN | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 26c | 47.4 | MN | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACATAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 27c | 47.3 | MN | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACATAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 28c | 48.1 | MN | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 29 | 45.3 | MA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGGCTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 30 | 45.1 | MA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGGCTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 31 | 45.5 | MA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGGCTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 32 | 45.5 | MA | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGGCTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 33c | 45.7 | AZ | CGAGATCGCACAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 34c | 46.0 | AZ | CGAGATCGCACAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 35 | 46.0 | AZ | CGAGATCGCACAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 36 | 47.3 | Kuwait | CGAGATCGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAATACAGATCTTGAGGC |

| 37 | 44.4 | NY | CGAGATTGCGCAGAGACTGGAAAGTGT | CT | TTGCAGGAAAGAACACAGATCTTGAGGC |

State where patient resided, specifically Ann Arbor, MI; Sewickley, PA; Beaver, PA; Cleveland, OH; Owatonna, MN; Racine, MN; Rochester, MN; Spring Valley, MN; Northampton, MA; Phoenix, AZ; Salusai, Kuwait; and Utica, NY.

CT is a two-base-pair sequence between the fluorescein probe and the red 640 probe.

Previously published sequences (3). One previously published sequence was not included in the final data due to inconsistent results.

All mutations are shown in bold.

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence of the 57-bp discriminatory region of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus.

Since the emergence of pandemic H1N1, several studies have tried to characterize the mutational trends of this new virus (4, 5, 7). Pan et al. described the emergence of a signature residue at the position of nucleoprotein 100 (NP-100) (valine to isoleucine) that exhibited a dominant change in as many as 93% of isolates by the later phases of the pandemic. In addition, four nonsignature residues, at positions neuraminidase 91 (NA-91), NA-233, hemagglutinin 206 (HA-206), and nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) to NS123, were observed during a short period of time within the epidemic (5). All of these mutant residues were characterized in the viral functional domains, suggesting potent roles in the human adaption and virulence. Mutations were also observed in M1/M2 genes, but they were of low frequency with an unknown role. Potdar et al. reported several mutations throughout the viral genome, including a predominant D225G mutation in the H gene present in the receptor binding domain of Indian novel H1N1 isolates (7). Nelson et al. conducted a whole-genome phylogenetic analysis on 290 isolates of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus collected globally and identified seven major clades that have cocirculated worldwide since April 2009 (4). Several amino acid changes were also identified, predominantly in the HA, NA, and NP genes. However, no mutations were observed in the matrix gene in the latter two studies.

In our study, we found eight mutations in a very short sequence span of only 57 bp of the influenza A virus matrix gene, of which two were nonsynonymous (Leu28Met and Thr37Ile). This is an unexpected finding, as the influenza A virus matrix gene is relatively conserved and is not thought to be under the same genetic selective pressures as other genes, such as HA and NA, that have very high mutability rates. The implications of these findings for viral adaptation and virulence have yet to be determined. However, from a diagnostic perspective, these mutations resulted in the loss of viral subtype discriminatory ability using Tm analysis within just 3 months of the pandemic and hindered laboratory diagnosis. Evidence for mutability in the highly conserved M gene of influenza virus calls for pandemic as well as routine in silico monitoring of primers and probes for optimal target coverage.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. Update: novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection—Mexico, March-May, 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58:585-589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawood, F. S., S. Jain, L. Finelli, M. W. Shaw, S. Lindstrom, R. J. Garten, L. V. Gubareva, X. Xu, C. B. Bridges, and T. M. Uyeki. 2009. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:2605-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhiman, N., M. J. Espy, C. Irish, P. Wright, T. F. Smith, and B. S. Pritt. 2010. Mutability in the matrix gene of novel influenza A H1N1 virus detected using a FRET probe-based real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:677-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson, M., D. Spiro, D. Wentworth, E. Beck, J. Fan, E. Ghedin, R. Halpin, J. Bera, E. Hine, K. Proudfoot, T. Stockwell, X. Lin, S. Griesemer, S. Kumar, M. Bose, C. Viboud, E. Holmes, and K. Henrickson. 2009. The early diversification of influenza A/H1N1pdm. PLoS Curr. Influenza Nov. 3:RRN1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Pan, C., B. Cheung, S. Tan, C. Li, L. Li, S. Liu, and S. Jiang. 2010. Genomic signature and mutation trend analysis of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus. PLoS One 5:e9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peiris, J. S., L. L. Poon, and Y. Guan. 2009. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A virus (S-OIV) H1N1 virus in humans. J. Clin. Virol. 45:169-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potdar, V. A., M. S. Chadha, S. M. Jadhav, J. Mullick, S. S. Cherian, and A. C. Mishra. 2010. Genetic characterization of the influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus isolates from India. PLoS One 5:e9693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. 2010. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009—update 104. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/updates/en/index.html.

- 9.Zitterkopf, N. L., S. Leekha, M. J. Espy, C. M. Wood, P. Sampathkumar, and T. F. Smith. 2006. Relevance of influenza A virus detection by PCR, shell vial assay, and tube cell culture to rapid reporting procedures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3366-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]