Abstract

Patent foramen ovale is increasingly diagnosed in patients who are undergoing clinical study for cryptogenic stroke or migraine. In addition, patent foramen ovale is often suspected as a cause of paradoxical embolism in patients who present with arterial thromboembolism. The femoral venous approach to closure has been the mainstay. When the femoral approach is not feasible, septal occluder devices have been deployed via a transjugular approach.

Herein, we describe 2 cases of patent foramen ovale in which the transhepatic approach was used for closure. To our knowledge, this is the 1st report of a transhepatic approach to patent foramen ovale closure in an adult patient. Moreover, no previous case of patent foramen ovale closure has been reported in a patient with interrupted inferior vena cava.

Key words: Brain ischemia/etiology; echocardiography, transesophageal; embolism, paradoxical/etiology/prevention & control; heart catheterization/methods; heart defects, congenital/therapy; hepatic veins; migraine disorders; patent foramen ovale; platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome; prosthesis implantation/methods

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is increasingly diagnosed in patients who are undergoing clinical study for cryptogenic stroke or migraine.1,2 In addition, patent foramen ovale is often suspected as a cause of paradoxical embolism in patients who present with arterial thromboembolism. The femoral venous approach to closure of PFOs has been the mainstay.3 In rare instances—when the surgeon is faced with an occlusion of the inferior vena cava (IVC) or with the presence of previously deployed filters, for example—an alternative approach will be necessary.

A few reports have been published of PFO closure in adults via the internal jugular vein approach.4 This, to our knowledge, is the 1st report of transhepatic closure of PFO in an adult patient, and we report 2 such cases.

Surgical Technique

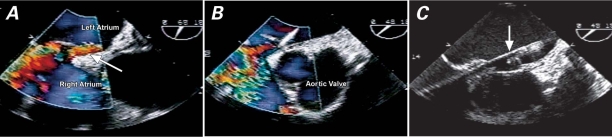

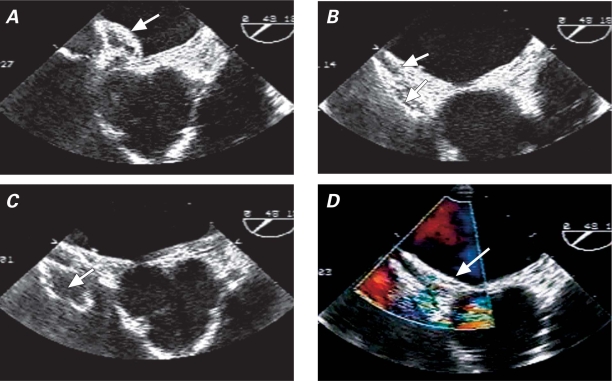

Our 2 patients with PFO received general anesthesia, and we used transesophageal echocardiography for guidance during the procedures. The right side of the abdomen was anesthetized in a sterile fashion. Under fluoroscopy, a 22G needle was inserted into the liver. Contrast agent was injected as the needle was withdrawn. When the needle tip was seen to be placed in a suitable hepatic vein, we inserted a guidewire, removed the needle, and passed a 6F sheath over the wire. When the contrast agent showed the catheter to be in one of the main hepatic veins, we advanced the catheter into the IVC over the wire (Figs. 1A and 1B). The wire was then exchanged for a stiff HI-TORQUE Supra Core® 35 Guide Wire (Abbott Vascular, part of Abbott Laboratories; Abbott Park, Ill), which was advanced into the left atrium. Once the interatrial septum had been crossed, we administered unfractionated heparin to both patients, for anticoagulation. The 6F sheath was exchanged for a 9F AMPLATZER® sheath (AGA Medical Corporation; Plymouth, Minn) in patient 1 and for a 10F AMPLATZER sheath in patient 2 (Fig. 1C). Once the appropriate size AMPLATZER occluder device (AGA Medical) had been deployed (Fig. 2), we removed the percutaneous sheath and closed the hepatic tract: in patient 1, we used Cook embolization coils (Cook Medical; Bloomington, Ind), and in patient 2, we used an 8-mm Nester® coil (Cook Medical). We deposited the coils into the hepatic parenchyma, then supplemented the coils with gel foam. Protamine sulfate was administered to reverse the anticoagulation.

Fig. 1 A) Transesophageal color-flow echocardiographic image shows flow (arrow) through the patent foramen ovale (PFO) with right-to-left shunt. B) Supra Core® wire is seen across the PFO. C) AMPLATZER® sheath (arrow) is stationed in the left atrium, across the PFO.

Fig. 2 Transesophageal echocardiography. A) Left atrial disc is deployed (arrow). B) Both discs are deployed (arrows) across the septum, before their final release from the delivery cable. C) Minnesota wiggle: “pull and push” maneuver (arrow) on the delivery cable. D) Final device deployment. No shunting into the left atrium (arrow) is evident upon color-flow Doppler imaging. The device appears to be well seated.

Patient 1

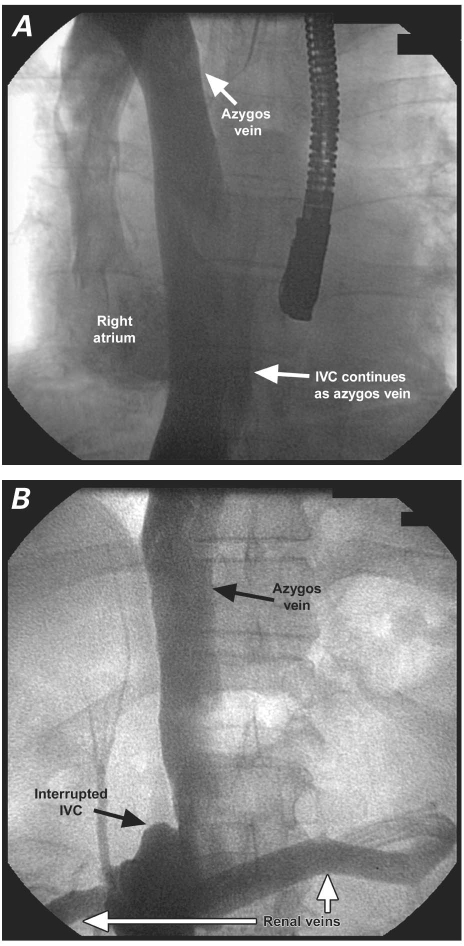

This patient was a 67-year-old man who was evaluated for a recent cryptogenic stroke. He was found to have a PFO with right-to-left shunt. In the course of our examination, we found that he also had an interrupted IVC (Fig. 3), the inferior portion of which drained into the azygos vein. After discussing alternative options for management, we decided to proceed with transhepatic closure of the PFO. Coronary angiography revealed no significant coronary artery disease. Right heart catheterization revealed normal pulmonary artery pressure and normal cardiac output. Under fluoroscopic and transesophageal guidance, we used a procedural technique similar to the one described above and deployed a 25-mm AMPLATZER “Cribriform” PFO occluder (AGA Medical) across the interatrial septum via the transhepatic approach. The procedure was completed without adverse sequelae.

Fig. 3 Patient 1. A) The azygos vein drains into the superior vena cava. B) The inferior vena cava (IVC) continues as the azygos vein, after interruption by both renal veins (white arrows), which drain into the IVC.

Patient 2

This patient was a 76-year-old woman with a history of deep venous thrombosis, recurrent pulmonary embolism, and IVC filter placement who presented with severe intermittent dyspnea, sometimes manifest at rest. Moreover, she had a history of noncompliance and, consequently, of difficult-to-manage anticoagulation. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed normal left ventricular systolic function and no valvular abnormalities of note. The patient also underwent a computed tomographic scan of the chest, which ruled out parenchymal lung disease and any new pulmonary embolism. A ventilation perfusion scan (V/Q) showed a low probability of pulmonary embolism. The patient's arterial blood gases revealed a pH of 7.4, a PCO2 of 26 mmHg, a PO2 of 60 mmHg, a bicarbonate of 20 mEq/L, and an oxygen saturation of 91% on room air. In addition, an intermittent intracardiac shunt was suspected.

Our pulmonary consultant suggested a detailed evaluation by means of right and left heart catheterization. Right and left heart catheterization were performed via the brachial approach. The patient's coronary arteries were angiographically normal. The pulmonary artery pressures, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and right ventricular pressure were normal. Transseptal penetration of the catheter into the left atrium revealed a left atrial oxygen saturation of 91%. A simultaneous transesophageal echocardiographic study, with a saline solution for contrast, revealed an aneurysm of the interatrial septum and right-to-left shunting at the atrial level. Our presumptive diagnosis was platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome, for which PFO closure was recommended. Due to the presence of a permanent IVC filter and the risk of its inadvertent displacement, we decided to close the PFO via a transhepatic approach. Using the technique described above, we deployed a 25-mm AMPLATZER “Cribriform” occluder and confirmed the accuracy of its position by transesophageal echocardiography and fluoroscopy (Figs. 1 and 2). On subsequent outpatient follow-up, the patient's oxygen saturation level had improved, as had her symptoms.

Discussion

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome is an uncommon condition characterized by dyspnea and arterial desaturation upon assuming an upright position. In some platypnea-orthodeoxia patients, symptoms are associated with an orthostatic increase in right-to-left shunt across an atrial septal defect or PFO. Previously, such defects were closed surgically. In recent years, improved devices and endovascular techniques have enabled routine percutaneous closure. In 2001, Rao and colleagues5 reported the percutaneous closure of atrial septal defects and PFOs in platypnea-orthodeoxia patients via a femoral venous approach. However, some patients present with vascular-access problems in the lower extremities that exclude this option. Sader and co-authors4 reported closure of PFOs in 2 patients via the right internal jugular venous approach. The transhepatic approach for cardiac catheterization has been used in pediatric patients,6,7 but not to our knowledge in adults.

Patients with an interrupted IVC pose a special challenge in the percutaneous closure of cardiac defects. After our successful application of the transhepatic approach in 2 patients, we can report that this approach is well tolerated and perhaps less traumatic (and less challenging from a technical standpoint) than is the jugular approach as applied to patients with compromised femoral access. The caveat is that this approach must be undertaken in collaboration with an experienced interventional radiologist.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Dr. Aubrey Palestrant for his invaluable assistance as radiologist, and we thank Frank Wallace for his help with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Jamal Hussain, MD, FACC, Arizona Heart Hospital & Institute, 1930 E. Thomas Rd., Phoenix, AZ 85016

E-mail: xnorbeht@yahoo.com

References

- 1.Lechat P, Mas JL, Lascault G, Loron P, Theard M, Klimczac M, et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med 1988;318(18):1148–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Anzola GP, Magoni M, Guindani M, Rozzini L, Dalla Volta G. Potential source of cerebral embolism in migraine with aura: a transcranial Doppler study. Neurology 1999;52(8): 1622–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Martin F, Sanchez PL, Doherty E, Colon-Hernandez PJ, Delgado G, Inglessis I, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with paradoxical embolism. Circulation 2002;106(9):1121–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Sader MA, De Moor M, Pomerantsev E, Palacios IF. Percutaneous transcatheter patent foramen ovale closure using the right internal jugular venous approach. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2003;60(4):536–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rao PS, Palacios IF, Bach RG, Bitar SR, Sideris EB. Platypnea-orthodeoxia: management by transcatheter buttoned device implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2001;54(1):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Johnson JL, Fellows KE, Murphy JD. Transhepatic central venous access for cardiac catheterization and radiologic intervention. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1995;35(2):168–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ebeid MR, Joransen JA, Gaymes CH. Transhepatic closure of atrial septal defect and assisted closure of modified Blalock/Taussig shunt. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2006;67(5):674–8. [DOI] [PubMed]