Abstract

Reduction in the incidence of high-risk sexual behaviors among HIV-positive men is a priority. We examined the roles of proximal substance use and delinquency-related variables, and more distal demographic and psychosocial variables as predictors of serious high-risk sexual behaviors among 248 HIV-positive young males, aged 15–24 years. In a mediated latent variable model, demographics (ethnicity, sexual orientation and poverty) and background psychosocial factors (coping style, peer norms, emotional distress, self-esteem and social support) predicted recent problem behaviors (delinquency, common drug use and hard drug use), which in turn predicted recent high-risk sexual behaviors. Hard drug use and delinquency were found to predict sexual risk behaviors directly, as did lower self-esteem, white ethnicity and being gay/bisexual. Negative peer norms strongly influenced delinquency and substance use and positive coping predicted less delinquency. In turn, less positive coping and negative peer norms exerted indirect effects on sexual transmission risk behavior through delinquency and hard drug use. Results suggest targeting hard drug use, delinquency, maladaptive peer norms, dysfunctional styles of escaping stress and self-esteem in the design of intervention programs for HIV-positive individuals.

Introduction

Although many HIV prevention programs have been successful when targeting HIV-negative persons, fewer interventions have been effective for the primary source of HIV transmission: people who are already HIV-positive (Crepaz & Marks, 2002; Kalichman et al., 2001). Advances in treatment have increased the lifespan and quality of life of HIV-infected individuals, which also increases the likelihood that they will engage in sexual behaviors. Increases in unprotected sexual risk acts, particularly among young gay and bisexual men, have been noted since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapies (CDC, 2001,2002; Wolitski et al., 2001). Therefore, the need for interventions that prevent others from contracting the infection has been heightened (Kalichman, 2000; Rotheram-Borus & Miller, 1998).

In this study, sociodemographics, peer norms, coping style and psychosocial factors of emotional distress, self-esteem and perceptions of social support are positioned as distal predictors of high-risk sexual transmission acts; problem behaviors are positioned as proximal predictors. Sociodemographics include ethnicity and poverty. African-American and white gay and bisexual youth are at higher relative risk of becoming infected than youth of other ethnicities (CDC, 2001; Simon et al., 1999). Poverty is anticipated to be associated with higher rates of sexual transmission acts; rates of HIV infection are highest in the lowest income neighborhoods in the United States (Diaz et al., 2001). Having friends who endorse deviant acts has been related to risky sexual acts (Dishion et al., 1999). Because it is likely that antisocial peer norms influence the sexual behaviors of HIV-positive youth as well, negative peer norms are included in our study as background predictors.

We hypothesize that a positive coping style will be associated with less high-risk sexual behavior. Avoidant coping has been linked to increases in risk acts, whereas taking positive actions decreases sexual risk acts (Avants et al., 2000; Stein & Nyamathi, 1999). High rates of sexual risk acts have been found among persons with mental health problems and psychiatric diagnoses (Avants et al., 2000; Carey et al., 2001). In a review of research among HIV-infected individuals, Kalichman (2000) reported that depression, anxiety and hostility have been associated with risky sex practices.

In contrast, personal resources that increase resiliency may buffer the emergence of transmission acts. Self-esteem has been associated with lower rates of unprotected sexual risk acts (Belgrave et al., 2000; Nyamathi et al., 1995). Studies among people living with HIV/AIDS indicate that increased social support buffers stress, has a mental health benefit and is associated with a better quality of life (Kelly & Kalichman, 2002; Leslie et al., 2002; Swindells et al., 1999).

In addition to the distal constructs mentioned above, we hypothesize that proximal problem behaviors occurring within the same time frame as transmission risk behaviors will be important correlates and predictors of sexual risk behaviors. Sexual risk acts among young people in general often cluster with substance use and delinquency as components of a more general problem behavior syndrome (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). We are particularly interested in the proximal role of substance use. We distinguish between more common drugs such as alcohol, marijuana and tobacco and hard drugs which, in this study, specifically include stimulants, inhalants, cocaine and hallucinogens: the so-called ‘club’ drugs which are often used in social venues and during sexual activities (Halkitis & Parsons, 2002). In our theoretical model, we positioned the more distal and enduring background sociodemographic and psychological variables as impacting recent problem behaviors of delinquent acts and substance use. In turn, delinquency and substance use are proximal predictors of highly risky sexual transmission acts.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted in nine adolescent clinical care sites in four AIDS epicenters, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco and Miami. Over a 21-month period, 393 youths living with HIV who received care at the sites were asked to participate in the study; 347 were recruited with informed consent (25 refused participation and 21 were too ill). Ethnically-diverse trained interviewers used computer-assisted interviewing techniques.

The sample had 250 males and 97 females. The sample size for the males was adequate for this analysis but there were not enough women. Two men were deleted due to missing data. Thus, the final sample includes 248 HIV-positive young men (mean age = 21.3 years, range = 15–24 years; 25 = heterosexual, 190 = exclusively gay, 33 = bisexual). The youth were 43% Hispanic-American, 19% African-American, 22% Caucasian, 4% Asian and 12% ‘other’. Ethnic proportions are representative of AIDS cases in the four sites.

Measures

Demographics

Ethnicity was represented by white (1 = yes, 0 = no), with others as the reference group. Sexual orientation was represented by one variable (1 = gay or bisexual, 0 = no). Age was not included because it was not associated significantly with any model variable.

Distal latent variable predictors of risk behaviors

‘Positive coping style’ was indicated by three three-item parcels formed from the nine-item Positive Coping sub-scale of the 76-item Dealing with Illness Questionnaire (Murphy et al., 2003). Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88. A Likert-style five-point response scale ranged from: 1 = never to 5 = always.

‘Negative peer norms’ were indicated by three Likert items, scaled from one to five, from the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors (Barrera et al., 1981) that asked ‘do most of your friends: (1) use alcohol; (2) use drugs; (3) have sex with several different people?’

‘Emotional distress’ was indicated by summed scores on three sub-scales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1993; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983): general anxiety, obsessive/compulsive and depression. Scores were on a five-point Likert response scale ranging from 0 = ‘not at all distressing’ to 4 = ‘extremely distressing’. Reliability coefficients reported by Derogatis (1993) for these scales are 0.81 for general anxiety, 0.83 for obsessive/compulsive and 0.85 for depression.

‘Self-esteem’ was assessed with Rosenberg’s (1965) ten-item Self-Esteem scale. Each item has a Likert scale ranging from 1 = ‘strongly agree’ to 4 = ‘strongly disagree’. A higher score indicates greater self-esteem. We used a sum score due to the high eigenvalue among the ten items (4.3).

‘Social support’ was assessed with three indicators: (1) how often respondents see important people in their lives, (2) how often they discuss their illness with important people in their lives and (3) how supportive the people in their lives are about their condition (Barrera et al., 1981; Stein & Rotheram-Borus, 2004).

‘Poverty’ was indicated by three items: (1) whether respondents have enough money to eat three well-balanced meals a day (1 = yes, 2 = sometimes, 3 = no); (2) their ability to get food (1 = available every day to 4 = food is difficult to get most days); and (3) the financial situation of their entire household (from 1 = comfortable to 4 = very poor, struggling to survive).

Proximal latent variable predictors

Delinquency was indicated by items that assessed whether they had recently: (1) held up or robbed someone; (2) broken into a house, building or car; or (3) exhibited destructiveness by breaking windows, writing on a building or slashing tyres. These items were selected by factor analysis of a larger questionnaire. Reliability of the scale has been in the acceptable range (e.g., alpha = 0.63–0.93).

‘Common drug use’ was indicated by the amount of daily use of tobacco and the frequency of use of alcohol and marijuana in the last three months. Daily use of tobacco was rated on a 0–6 scale (0 = none to 6 = 2 packs a day or more). Other substance use variables both for ‘common drug use’ and ‘hard drug use’ were coded (0 = never to 7 = 200 or more times).

‘Hard drug use’ was indicated by the frequency of use over the last three months of stimulants, inhalants, hallucinogens and cocaine or crack cocaine. Scaling is described above.

Outcome sexual transmission risk behaviors

Three measured variables were selected as indicators of a latent variable representing serious risky sexual behaviors within the past three months: (1) whether respondents were sexually active and never used a condom (0 = no, 1 = yes); (2) the percentage of their sex partners that they did not inform that they were HIV-positive; and (3) the number of sex partners they reported in the last three months.

Analyses

Analyses were performed using the EQS structural equation modeling program (Bentler, 2005). The Robust CFI (RCFI), the adjusted Satorra–Bentler robust χ2 (S–B χ2) and the Root Mean Square Errors of Approximation (RMSEAs) were used to indicate fit (Ullman & Bentler, 2003). Robust statistics were used because the data were multivariately kurtose. Values approaching 0.95 or greater are desirable for the RCFI; an RMSEA less than 0.06 indicates a close-fitting model (Ullman & Bentler, 2003).

Results

Risky sexual behaviors

A substantial number of the men reported serious high-risk behaviors in the past three months: 23% reported never using a condom during sex, 12% did not always reveal their HIV-positive status to sex partners and 6% revealed their status half of the time or less. The young men averaged nearly seven sexual partners in the last three months. Only 17% reported no sex partners.

Latent variable analysis

A confirmatory model estimated the factor structure and relationships among the latent and–demographic variables. Table I reports summary statistics of the measured variables and their factor loadings. All factor loadings were significant (p ≤ 0.001). Fit indexes were all in the acceptable range: S–B χ2 = 458.02, 368 df ; RCFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.03. Table II reports the bivariate correlations among constructs of the model. Focusing on the outcome measure, sexual transmission risk behaviors were significantly associated with white ethnicity, identifying as gay or bisexual, a less positive coping style, more negative peer norms, more emotional distress and lower self-esteem. The cluster of problem behaviors—delinquency, common drug use, hard drug use and sexual transmission risk behaviors—were all associated highly among themselves.

Table I.

Summary statistics and factor loadings in the confirmatory factor analysis.

| Range | Mean (SD) | Factor loading* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | (0–1) | 0.22 (0.41) | NA |

| Gay/bisexual | (0–1) | 0.90 (0.30) | NA |

| Positive coping style | |||

| Positive1 | (1–5) | 3.73 (1.15) | 0.87 |

| Positive2 | (1–5) | 3.36 (1.10) | 0.87 |

| Positive3 | (1–5) | 3.32 (1.05) | 0.83 |

| Negative peer norms | |||

| Friends use alcohol | (1–5) | 2.48 (1.13) | 0.48 |

| Friends use drugs | (1–5) | 2.17 (1.14) | 0.91 |

| Friends—multiple sex partners | (1–5) | 2.74 (1.13) | 0.33 |

| Emotional distress | |||

| Depression | (0–4) | 1.15 (0.95) | 0.87 |

| Anxiety | (0–4) | 0.99 (0.95) | 0.90 |

| Obsessive/compulsive | (0–4) | 1.07 (0.97) | 0.88 |

| Self-esteem | (1–4) | 3.05 (0.47) | 1.00 |

| Social support | |||

| How often see | (0–10) | 2.46 (1.98) | 0.54 |

| Discuss | (0–8) | 1.26 (1.41) | 0.63 |

| Support | (0–10) | 2.80 (2.25) | 0.72 |

| Poverty | |||

| Enough money (R) | (1–3) | 1.77 (0.85) | 0.47 |

| Ability to get food (R) | (1–4) | 1.52 (0.78) | 0.48 |

| Financial situation (R) | (1–4) | 2.17 (0.98) | 0.55 |

| Delinquency | |||

| Hold up, robbery | (1–2) | 1.03 (0.18) | 0.83 |

| Break in | (1–2) | 1.05 (0.22) | 0.71 |

| Destructiveness | (1–2) | 1.08 (0.28) | 0.61 |

| Common drug use (last 3 months) | |||

| Alcohol frequency | (0–7) | 2.06 (1.72) | 0.33 |

| Cigarette frequency | (0–6) | 1.97 (1.84) | 0.44 |

| Marijuana frequency | (0–7) | 1.52 (1.08) | 0.71 |

| Hard drug use (last 3 months) | |||

| Stimulants | (0–7) | 0.80 (1.57) | 0.53 |

| Inhalants | (0–7) | 0.25 (0.81) | 0.32 |

| Cocaine/crack | (0–7) | 0.22 (0.63) | 0.42 |

| Hallucinogens | (0–7) | 0.25 (0.75) | 0.60 |

| Sexual transmission risk behavior (last 3 months) | |||

| Never use condom | (0–1) | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.63 |

| Percent of partners don’t tell HIV-positive | (0–97) | 0.06 (0.20) | 0.49 |

| Number of sex partners | (0–360) | 6.88 (30.26) | 0.70 |

All factor loadings significant (p ≤ 0.001).

Table II.

Correlations among constructs and demographics.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. White | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Gay/bisexual | 0.02 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Positive coping style | −0.12 | 0.02 | – | ||||||||

| 4. Negative peer norms | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.01 | – | |||||||

| 5. Emotional distress | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.25*** | – | ||||||

| 6. Self-esteem | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.32*** | −0.12 | −0.51*** | – | |||||

| 7. Social support | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.19** | −0.09 | −0.12 | 0.31*** | – | ||||

| 8. Poverty | −0.15* | −0.08 | −0.14 | 0.12 | 0.37*** | −0.37*** | −0.18* | – | |||

| 9. Delinquency | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.15* | 0.25*** | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.16* | 0.15 | – | ||

| 10. Common drug use | 0.12 | 0.24*** | −0.01 | 0.53*** | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.41*** | 0.31*** | – | |

| 11. Hard drug use | 0.12 | 0.15* | −0.05 | 0.56*** | 0.17* | −0.12 | −0.02 | 0.23* | 0.41*** | 0.75*** | – |

| 12. Sexual transmission risk behaviors | 0.15* | 0.20** | −0.17* | 0.24** | 0.16* | −0.19** | −0.11 | 0.11 | 0.35*** | 0.29*** | 0.39*** |

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ .001.

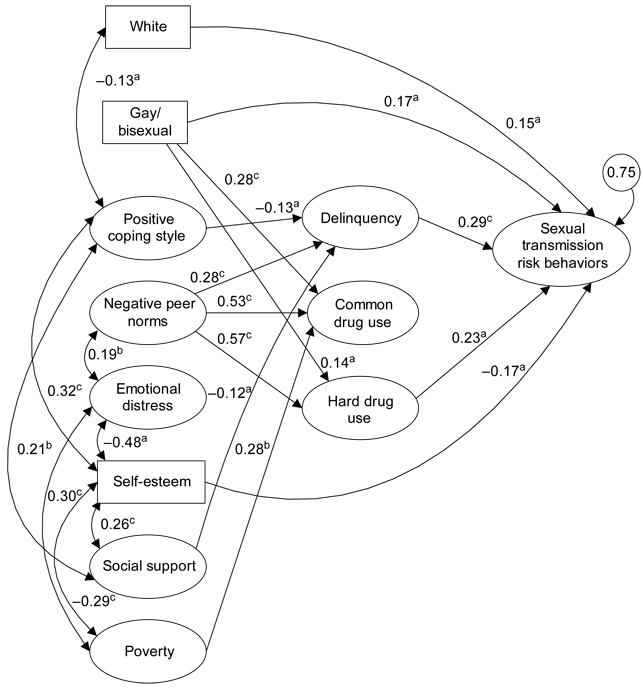

The final predictive model is presented in Figure 1. Fit indexes were acceptable: S–B χ2 = 495.97, 410 df ; RCFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.03. The proximal variables of ‘delinquency’ and ‘hard drug use’ significantly predicted sexual transmission risk behaviors. ‘Sexual transmission risk behaviors’ were also significantly predicted by being gay/bisexual, white and having less self-esteem. ‘Positive coping style’ (p ≤ 0.05) and ‘negative peer norms exerted indirect effects on sexual risk behavior (p ≤ 0.01) mediated through ‘delinquency’ and ‘hard drug use’.

Figure 1.

Significant regression paths predicting sexual transmission risk behaviors among 248 HIV-positive men. Large circles represent latent variables; rectangles represent single-item indicators. Single-headed arrows represent regression coefficients; double-headed arrows represent correlations. Regression coefficients are standardized (a = p ≤ 0.05, b = p ≤ 0.01, c = p ≤ 0.001).

Discussion

Our findings underscore the importance of recognizing the constellation of interrelated problem behaviors that contribute to unsafe sex practices among HIV-positive young men, including both hard drug use and delinquent behavior. Furthermore, the latent variable representing transmission risk behaviors is not a ‘combination’ but rather, as a more abstract latent variable, reflects what is common among the risky behavior indicators. It represents their shared variance, which is a strength of employing a latent variable approach in analyzing psychosocial data.

Looking at the individual indicators of transmission risk behavior, we provide support for prior research indicating that HIV-positive young men engage in risky sexual behavior despite their serostatus (Reilly & Woo, 2001). The young men averaged almost seven sex partners in the past three months and almost a quarter of them reported that they never used condoms during sexual acts. Only 17% reported that they had not engaged in any sexual behavior in the last three months.

Except for social support and poverty, all of the variables included in our confirmatory model were significantly associated bivariately with highly risky sexual behavior. However in the more stringent predictive model, being white, identifying as gay/bisexual, reporting less self-esteem, engaging in delinquent behaviors and using hard drugs predicted risky sexual behaviors. The significance of hard drug use along with the association between a gay or bisexual orientation and more risky sexual behavior supports the findings of Halkitis and Parsons (2002) and Halkitis et al. (2001) about the impact and association with risk of the so-called ‘club drugs’.

Another compelling finding is the association of sexual transmission risk behaviors with delinquent acts such as robbery, breaking and entering and other property crimes reflecting the constellation of problem behaviors that are associated with general risk proneness and deviancy (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Further, the relationship between drug use and delinquency should be considered in interventions; treating substance abuse can decrease delinquent behaviors (Dembo & Pacheco, 1999). Thefts and other property crimes are often associated with the need for money for illicit drugs.

Gay/bisexual males were engaging in more risky sexual behaviors than the heterosexual males. This may indicate a need for special outreach among HIV-positive gay males that helps deal with issues relevant to them. For instance, hard drug use presents serious problems for the gay community (Dolezal et al., 1997; Halkitis et al., 2001).

Implications for the design of intervention programs

Multifaceted prevention strategies are needed that target distal demographic, and psychosocial factors such as self-esteem, peer relationships and proximal problem behaviors such as substance use and/or delinquent behavior. Various strategies have been employed to intervene for delinquent behaviors, but one of the most effective techniques is multisystemic therapy that targets delinquent behaviors within familial and community contexts (Brown et al., 1997). Interventions that rely on cognitive restructuring and behavioral skill development often target coping styles, peer behaviors and social support.

HIV prevention programs for HIV-positive individuals should recognize the centrality of substance abuse. Meta-analysis has shown the value of including HIV risk-reduction interventions in substance abuse treatment programs (Prendergast et al., 2001). Shoptaw and Frosch (2000) have also stressed the importance of substance abuse treatment as an HIV prevention method.

Intervention programs for HIV-positive young men need to include substance abuse treatment components but also should target coping styles and peer relationships. Our models show pathways from negative peer norms to more hard drug use and from less positive coping to more delinquency, which in turn predicted more sexual risk behavior. Rotheram-Borus and her colleagues (Lightfoot et al., in press; Rotheram-Borus, 1997; Rotheram-Borus & Miller, 1998; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1999a,b, 2001a,b) have developed interventions for HIV-positive men that address substance abuse through cognitive restructuring and behavioral skills training. Participants learn how to identify triggers (e.g., negative emotions or stressful situations) that lead to substance abuse, and also learn more appropriate coping styles and behavioral skills to avoid alcohol and other drugs.

Limitations

Unfortunately, information on selection of seroconcordant sexual partners and specific emotional trauma related to knowledge of HIV-positivity was not available. We also do not have measures related to the specific peer behaviors most associated with HIV risk. Rather, the peers’ latent variable served as a more generalized indicator of associations with deviant peers as an important component of problem behavior theory.

The purpose of this paper was to focus in on very risky behaviors among those already HIV-positive. Many studies have used cognitive predictors but have had limited success in predicting behaviors with them. We took the strategy of seeing whether general problem behaviors measured proximally with the HIV risk behaviors would explain more variance in high-risk sexual behaviors than psychosocial variables and sociodemographics. We recognize that any one behavior is part of an interwoven and connected pattern of complex behaviors performed by the individual; temporal precedence is often difficult to ascertain when using cross-sectional data. In particular, drugs are often used in association and concurrently with sexual activities. Our overall model is reasonable, in that we place more enduring distal traits as predictors of current problem behaviors that include the sexual risk behaviors. Also, we depended on self-reports, which can be inaccurate.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by Grants PO1 DA01070-30 and RO1 DA07903 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Grant P30 MH58107 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Gisele Pham for her secretarial and administrative contributions.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

References

- Avants SK, Warburton LA, Hawkins KA, Margolin A. Continuation of high-risk behavior by HIV-positive drug users: Treatment implications. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;19:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Sandler I, Ramsey T. Preliminary development of a scale of social supports of college students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1981;9:435–447. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave FZ, Van Oss Marin B, Chambers DB. Cultural, contextual, and intrapersonal predictors of risky sexual attitudes among urban African American girls in early adolescence. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6:309–322. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, Swenson CC, Cunningham PB, Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Rowland MD. Multisystemic treatment of violent and chronic juvenile offenders: Bridging the gap between research and practice. Administration & Policy in Mental Health. 1997;25:221–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1022247207249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Vanable PA. Prevalence and correlates of sexual activity and HIV-related risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:846–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Young people at risk: HIV/AIDS among America’s youth. 2001 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/facts/youth.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men—New York City. Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 2002;51:854–875. [PubMed]

- Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: A review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16:135–149. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo R, Pacheco K. Criminal justice responses to adolescent substance abuse. In: Ammerman RT, Ott PJ, Tarter RE, editors. Prevention and societal impact of drug and alcohol abuse. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring, & procedures manual. Minneapolis, Mi: National Computer Systems, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from three US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal C, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Remien RH, Petkova E. Substance use during sex and sensation seeking as predictors of sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay men. AIDS & Behavior. 1997;1:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Recreational drug use and HIV-risk sexual behavior among men frequenting gay social venues. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2002;14:19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Stirratt JJ. A double epidemic: Crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41:17–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. HIV transmission risk behaviors of men and women living with HIV-AIDS: Prevalence, predictors and emerging clinical interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2000;7:32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, Luke W, Buckles J, Kyomugisha F, Benotsch E, Pinkerton S, Graham J. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Kalichman SC. Behavioral research in HIV/AIDS primary and secondary infection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:626–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie MB, Stein JA, Rotheram-Borus MJ. The impact of coping strategies, personal relationships and emotional distress on the health-related outcomes of parents living with HIV or AIDS. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Milburn N, Swendeman DT. Prevention for HIV seropositive persons: Successive approximation towards a new identity. Behavior Modification. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272599. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Marelich W. Factor structure of a coping scale across two samples: Do HIV-positive youth and adults utilize the same coping strategies? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:627–647. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Stein JA, Brecht M. Psychosocial predictors of AIDS risk behavior and drug use behavior in homeless and drug-addicted women of color. Health Psychology. 1995;14:265–273. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML, Urada D, Podus D. Meta-analysis of HIV risk-reduction interventions within drug abuse treatment programs. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:389–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly T, Woo G. Predictors of high-risk sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS & Behavior. 2001;5:205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ National Institutes of Health. Interventions to reduce heterosexual transmission of HIV. Interventions to prevent HIV risk behaviors: Program & abstracts; NIH Consensus Development Conference; Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1997. pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Miller S. Secondary prevention for youths living with HIV. AIDS Care. 1998;10:17–34. doi: 10.1080/713612347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JM, Lightfoot M. Teens linked to care consortium: Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youths living with HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2001a;91:400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mann T, Chabon B. Amphetamine use and its correlates among youths living with HIV. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1999a;11:232–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Swendeman D, Chao B, Chabon B, Zhou S, Birnbaum J, O’Hara P. Substance use and its relationship to depression, anxiety and isolation among youth living with HIV. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999b;6:293–311. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0604_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Wight RG, Lee MB, Lightfoot MA, Swendeman D, Birnbaum JM, Wright W. Improving the quality of life among young people living with HIV. Evaluation & Program Planning. 2001b;24:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Frosch D. Substance abuse treatment as HIV prevention for men who have sex with men. AIDS & Behavior. 2000;4:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Simon PA, Thometz E, Bunch JG, Sorvillo F, Detels R, Kerndt PR. Prevalence of unprotected sex among men with AIDS in Los Angeles County, California 1995–1997. AIDS. 1999;13:987–990. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905280-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Nyamathi A. Gender differences in relationships among stress, coping and health risk behaviors in impoverished populations. Personality & Individual Differences. 1999;26:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations in coping strategies and physical health outcomes among HIV-positive youth. Psychology & Health. 2004;19:321–336. [Google Scholar]

- Swindells S, Mohr J, Justis JC, Berman S, Squier C, Wagener MM, Singh N. Quality of life in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: Impact of social support, coping style and hopelessness. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1999;10:383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB, Bentler PM. Structural equation modeling. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology, Volume 2. Research Methods in Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2003. pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, Levine WC. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:883–888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]