Abstract

This article presents a three-module intervention based on social action theory that focuses on health promotion and social identity formation for seropositive youth. The modules are designed to reduce transmission of HIV by reducing sexual and substance abuse acts, increasing healthy acts and adherence to care, and maintaining positive behavioral routines. Components of the modules are described, including examples of how these components are implemented in the actual intervention sessions. The importance of using successive approximation to consolidate changes in behavior by defining social roles and personal identities that are consistent with positive behavioral routines is demonstrated. Outcomes of the intervention are presented as well as issues of cost-effectiveness, feasibility, and alternative implementation strategies.

Keywords: HIV, intervention, prevention

HIV infection among adolescents and young adults is a significant and growing problem. It is estimated that 50% of HIV infections worldwide and 25% of HIV infections in the United States are acquired in adolescence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999; UNAIDS, 1998). There are currently more than 31,000 identified cases of AIDS among 13- to 24-year-olds in the United States and more than 23,000 additional infections identified in the confidential surveillance system (CDC, 2000a). Estimates of the number of Youth Living with HIV (YLH) are typically based on studies of high-risk adolescents: gay and bisexual males (9% to 17%; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2003), injecting drug users (27% to 40%; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1995), homeless youth (4%; Stricof, Kennedy, Nattell, Wiesfuse, & Novick, 1991), and young women in prenatal clinics (0.4%; CDC, 1995), yielding estimates of YLH in the United States between 110,000 and 250,000 (Johnson, 1996; Rotheram-Borus, O'Keefe, Kracker, & Foo, 2000). Only about 5% to 10% of YLH are being served in medical clinics in the United States (Rotheram-Borus, O'Keefe, et al., 2000). Comparing these estimates with the CDC reports of identified infections indicates that from 20% to 50% of the HIV infections among youth have not been identified. Early detection will be increasingly emphasized with the further advancement of antiretroviral therapies. Enhanced detection will also create opportunities to intervene with more seropositive persons at younger ages.

Traditional youth prevention programs have targeted either youth in school (Kirby, 2000) or inner-city minority youth who engage in high-risk acts (Jemmott & Jemmott, 2000, or Rotheram-Borus, O'Keefe, et al., 2000, for a review). Both of these groups are typically seronegative for HIV, yet it is infected persons who will transmit the infection. The goal of this article is to outline an efficacious prevention program for seropositive young people. We will describe the transmission issues that are particularly salient to YLH, the theoretical perspective that guides the intervention, the content of the intervention, and outcomes that we have obtained in YLH.

Intervention Rationale

Geographically, YLH are clustered in inner-city epicenters: New York, Miami, San Francisco, and Los Angeles (CDC, 2000b). Adolescent females are at higher relative risk for HIV infections; 64% of seropositive 13- to 19-year-olds and 49% of 13- to 24-year-olds are female (CDC, 2000a). However, most infected young persons are gay and bisexual males aged 13 to 24 years (CDC, 2000a). African American and Latino youth are overrepresented among the infected (CDC, 2000a); 76% of females and 57% of males were members of ethnic minority groups and were typically from poor urban neighborhoods. Thus, youth at greatest risk are those who are also likely to be disenfranchised in other ways, in addition to having the HIV infection.

There have been major breakthroughs in diagnosis and treatment for HIV since 1996. With the introduction of antiretroviral therapies, the number of people dying from AIDS-related illnesses has declined (Lee & Rotheram-Borus, 2001). For antiretroviral therapies to be effective, however, YLH must come in for treatment and adhere to their medical regimes. Adherence is particularly difficult with youth. YLH often are not future oriented, and they are not willing to comply with a medical regimen that requires following a very structured medication schedule of multiple drugs at specific times, for example, 20 to 30 pills six times per day (Chow, Chin, Fong, & Bendayan, 1993). Many YLH have substance abuse problems that can interfere with their ability to adhere to daily health care regimens (Finney, Hook, Friman, Rapoff, Christophersen, 1993; I. M. Friedman & Litt, 1986). Consequently, antiretroviral therapies alone are not the best intervention for YLH.

Many YLH reduce their transmission behaviors when they learn that they are HIV-seropositive (Rotheram-Borus & Futterman, 2000; Rotheram-Borus, O'Keefe, et al., 2000). For example, during their lifetime, 19% of YLH in our sample had been injecting drug users, similar to national reports (11% of adolescent AIDS cases; CDC, 1995). Yet when recruited into the study, more than 50% of the male injecting drug users had stopped injecting drugs. Most youth (68%) had used hard drugs; however, at recruitment, marijuana and alcohol were the dominant drugs (Rotheram-Borus, Murphy, et al., 2000).

It is critical that YLH who continue transmission behaviors receive special preventive interventions. Substance use among our previous sample of YLH was linked to the risk of transmitting HIV through injecting drug use and other substance use associated with sexual risk behavior (Rotheram-Borus, O'Keefe, et al., 2000). Use of substances and sexual risk were linked over time among young people living with HIV (Rotheram-Borus, Lee, et al., 2000). Substance use has also been associated with continued patterns of high-risk sex among HIV-positive adults (Edlin, et al., 1994; Kalichman, Greenberg, & Abel, 1997; Kelly et al., 1993). Substance use among HIV-positive persons also appears linked to depressive symptoms and disorders (S. R. Friedman, Wiebel, Jose, & Levin, 1993; Rotheram-Borus, Murphy, et al., 2000), a factor related to both increased sexual risk and lower health adherence (L. N. Friedman, Williams, Singh, & Frieden, 1996). Therefore, decreasing substance use must be a primary outcome of all secondary prevention programs with YLH.

For society, it is also critical to reduce transmission of HIV through sexual risk acts among YLH. Young people are more likely to have frequent sexual partners (Kirby et al., 1994), and the current evidence suggests that young people living with HIV may not become symptomatic for up to 10 years (CDC, 1998). If YLH continue to have frequent unprotected sex, the number of persons likely to become infected with HIV during 10 years is substantial. Therefore, encouraging and motivating YLH to protect their sexual partners is important. Altruism, or protecting another person, is a likely motivation for reducing transmission risk. Furthermore, YLH who are symptomatic and who do not adhere to health care are likely to have more costly medical bills. These are emerging treatment issues for seropositive persons that are likely to be dramatically affected by youth's substance use. One module of the intervention builds on motivations of altruism and caring for others to reduce substance use, as well as sexual risk acts.

To prevent YLH from infecting others, however, requires long-term maintenance of behavior change. There is evidence among adult gay men that relapse of high-risk sexual behavior is common (Kelly, St. Lawrence, Betts, Brasfield, & Hood, 1990; Wolitski, Valdiserri, Denning, & Levine, 2001). Relapse is especially likely among the younger gay males (Kelly et al., 1990), suggesting it may be an even greater problem among adolescents. Given these concerns, a module focuses on improving the quality of life and reducing relapse. This module aims to reduce depression, increase acceptance, and maintain a high quality of life on an ongoing basis.

An Intervention for YLH

Across distinct populations, such as gay and bisexual men and heterosexual women involved with substance users and injection drug users, the goals of secondary prevention programs are similar: (a) to stop the spread of HIV by eliminating sexual and substance use transmission acts, (b) to increase healthy acts and adherence to health care, and (c) to maintain these positive behavioral routines over time. We designed a three-module intervention based on these three goals.

Theoretical Model: Social Action Theory

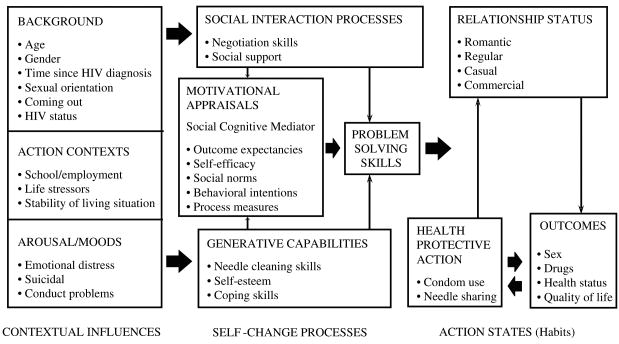

Interventions for substance abuse emphasize complex physiological, psychological, and social bases, including youth's life skills (Botvin & Kinder, 1987). Learning that one is HIV seropositive, however, increases the motivation for risk reduction, particularly substance use. Therefore, we adapted the social action model (Ewart, 1991) to guide the development of the intervention for YLH as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical model underpinning the intervention and the assessment based on social action.

SOURCE: Ewart (1991).

Developed as a health promotion theory for behavioral medicine problems (heart attacks, hypertension), the social action model expands existing HIV-related social-cognitive models (Bandura, 1977; Catania, Kegeles, & Coates, 1990; Fishbein & Reuland, 1994; Janz & Becker, 1984) by specifically targeting contextual influences on substance use and behavior change, self-regulation processes, social relationships, and health promotion. The activities and the sequence of activities designed to reflect this model were well received by YLH; the process ratings were so uniformly high that the ratings could only be used as a check of the satisfaction. The intervention also resulted in positive outcomes, again an indication that the theoretical model was appropriate (Rotheram-Borus, Lee, et al., 2001).

We based the selection of the theoretical model on an ethnographic study that was conducted to identify key theoretical concepts for adolescents, as well as the contextual influences on the lives of YLH that were likely to influence the design and effectiveness of any intervention program. The ethnographic interviews identified a series of steps that YLH experience in adapting to their serostatus: (a) establish an identity, (b) reflect this identity in the social roles demonstrated by the youth, and (c) engage in behavioral routines that enact the roles within a variety of settings in daily life and in specific behaviors, such as decreases in the number of unprotected sexual risk acts or substance use.

YLH must shift their identity to being an HIV-positive person and this status changes many of youth's social relationships in fundamental ways. When one is serospositive, a new set of interpersonal relationships, particularly with families and romantic partners, develops. The meaning of unprotected sex with one's partners, the sexual acts within a relationship, any plans for children, the meaning of trust and of protection, and daily routines shift when one learns of a seropositive status. News that one is seropositive often leads to a role reversal between adolescents and their parents: The parents often need to be comforted by the youth who is disclosing their serostatus. In these cases, the adolescents are not only coping with their own reaction to their serostatus, but are supporting their parents as they process the information. The program is likely to fail if those providing HIV interventions ignore these pervasive changes in social identities and social roles.

Rather than solely focusing on social-cognitive skill factors, this intervention addresses the identity formation of YLH as a means of youth achieving desired behavior change. Erikson (1968) identified adolescence as the period when roles are acquired and role-related skills, capacities, and preferences are developed. Predictably, when adolescents learn that they are seropositive for HIV, existing developmental tasks regarding their identification and differentiation of identity remain challenges. These changes in social identity are then reflected in the behavioral routines of YLH.

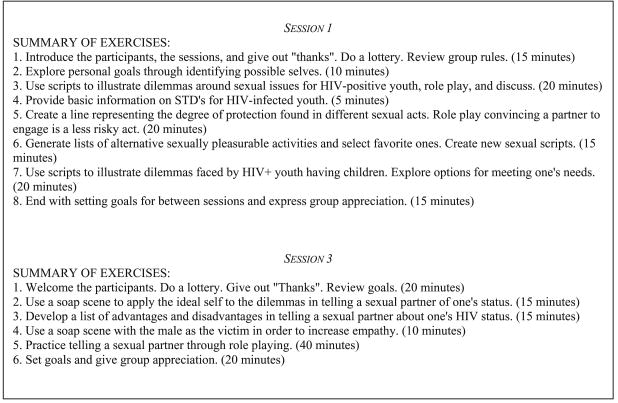

Thus, the content of the prevention intervention was varied by module: staying healthy, reducing transmission acts, and maintaining change over time. Each module consists of 8 to 12 sessions in small groups of 8 to 12 youth each with two coleaders. Table 1 summarizes the content of each module during the 31 sessions. Intervention manuals are available from the second author (Rotheram-Borus & Miller, 1998) and are available on our Web site: http://chipts. ucla.edu. First, we will briefly review each module to present the key intervention components. Second, we will illustrate how identity formation is used throughout the intervention to address the initiation of new behaviors, specifically disclosure.

TABLE 1. Session Content in Each Module of the Intervention for Youth Living With HIV.

| Session | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Module 1: Stay Healthy | ||

| 1 | Attitudes toward living with HIV | |

| 2 | Exploring future goals | |

| 3 | Disclosure of status | |

| 4 | Coping with stigma | |

| 5 | Staying healthy | |

| 6 | Drug and alcohol use | |

| 7 | Changing substance abuse | |

| 8 | Preventing reinfection | |

| 9 | Staying calm | |

| 10 | Attending health care appointments | |

| 11 | Taking prescribed medications | |

| 12 | Participating in medical care decisions | |

| Module 2: Act Safe | ||

| 1 | Protecting yourself and your partner | |

| 2 | Selecting protection methods and sex acts | |

| 3 | Disclosing your serostatus to your partner | |

| 4 | Getting a partner to accept using condoms | |

| 5 | Refusing unprotected sex | |

| 6 | Establishing the commitment to be drug-free | |

| 7 | Stopping drug and alcohol thoughts | |

| 8 | Avoiding external triggers | |

| 9 | Avoiding internal triggers | |

| 10 | Handling anxiety and anger to reduce drug use | |

| 11 | Handling drugs, alcohol, and sex | |

| Module 3: Being Together | ||

| 1 | How can I have a better quality of life? | |

| 2 | How can I reduce negative feelings? | |

| 3 | Who am I? | |

| 4 | Is what I see the real thing? | |

| 5 | What direction should I follow? | |

| 6 | How can I be a good person? | |

| 7 | How can I get wise? | |

| 8 | How can I care about others? |

Module 1: Stay healthy

Typically, YLH are not initially clear that attending the intervention will be meaningful to them. Thus, Module 1 focuses on the issues most salient to YLH: (a) emotional reactions to needing to give up drug abuse and seek consistent medical care, (b) knowledge about the course of HIV infection, (c) motivation for staying healthy, (d) gaining access to resources for obtaining medical care, (e) building drug-free social networks, and (f) becoming an active participant in their own medical care along with their physician. Each session within Module 1 has specific objectives. For example, in Session 1, YLH target (a) identifying positive life goals and then making a commitment to obtaining what they want and (b) confronting their attitudes toward being HIV-positive. Each session builds logically on the previous one to create motivation for change. First, youth disclose their current attitudes toward living with HIV. Youth then identify and prioritize their most important values and goals. After addressing positive attitudes toward HIV, YLH will consider the reasons why HIV is important in their life, practice arguing against negative self-statements, identify situations in their life that they want to improve, and develop long-term goals in multiple areas of their life. Substance use is consistently highlighted as a behavior that blocks identification of goals, values, and rewards.

Skills training (interpersonal problem-solving ability, social skills, condom use, and needle cleaning) and access to comprehensive care are identified as prerequisites to safe acts. Interpersonal problem solving refers to the YLH's ability to set goals, generate alternatives to meet those goals, evaluate the means required to implement various alternatives, select one alternative, and evaluate the success of one's efforts (Spivack, Platt, & Shure, 1976). The training helps youth identify and analyze an interpersonal problem in terms of the risks, costs, and opportunities that it offers in relation to one's needs (e.g., “This is the kind of situation that could easily lead to unsafe sex, which I am trying to avoid”) and then consider and evaluate alternative ways of handling the situation. Three behavioral skills are targeted: (a) making clear requests, (b) making clear refusals, and (c) coping with criticism. Specific content and the wording of vignettes are based on the findings of the ethnographic work. The training includes role-playing and coaching. Access to health, mental health care, and condoms are resources that are necessary to maintaining safe acts and are provided at each intervention site.

Although the entire second module is devoted to reducing risk acts, given the high negative consequences of transmission behaviors, initial attention is given during Module 1 to reduce drug and alcohol use and sexual behaviors, which are major barriers to enacting any other health behaviors. In Module 2, more specific risk-reduction skills are taught after motivation and healthy behaviors have been established in Module 1. We introduce the changes in substance use early in Module 1 by having youth practice identifying thoughts, beliefs, and actions that lead to continued substance use, to identify their own thoughts in a substance use event, to learn strategies to help them self-monitor their thoughts in substance use situations, and to question their beliefs regarding substance use. From past experience in working with YLH, we have chosen to focus less on changing cognitions and more on stopping initial self-destructive patterns from being established. Either way, it is necessary to recognize drug-related thoughts and permission-giving thoughts. The basic pattern followed is trigger → thought → craving→use. The basic strategy is to interrupt this cycle by interrupting the behavior chain early by avoiding triggers and preventing thoughts from progressing. Furthermore, as most people who are chronic substance users have chaotic lives with many other problems, each session sets aside a period of time for problem solving a current crisis situation.

Sessions are structured to avoid a sense of disorganization in the treatment. For the youth to be able to apply to real life the skills taught during the sequential exercises, they must practice the skills in sessions under conditions wherein they are emotionally aroused.

Although the substance use and sexual risk acts are targeted somewhat in Module 1, health care behaviors are the primary focus. By addressing health care, we begin with motivations for self-preservation. Youth then identify criteria for selecting and trusting a physician, identifying where and how to get information on their illness, problem-solving barriers to being a partner in their health care, practicing interacting assertively with their physicians around medical issues of importance to them, and setting goals to become a partner in their medical care. Researchers have found that the perceived degree of control influences the longevity and quality of life of persons with chronic and terminal illness (UCLA Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services, 1999). One area in which increased control can occur is in the patient's relationship with his or her physician. Our goal is to create a partnership arrangement to enhance control over an important area of an HIV-positive youth's life. Dealing with issues of physician selection, trust, increased knowledge, and assertiveness in physician and patient interactions can all contribute to a sense of greater control.

Module 2: Reducing risk

To gain commitment to a lifestyle free from transmission behaviors, it is assumed that all participants can set an individualized goal regarding stopping, reducing, or maintaining a low level of drug and alcohol use and increasing safer sex. To help youth set goals of abstinence, this module reviews the trigger-thought-craving-use model of substance use and helps YLH acquire skills for self-regulation. We assume that the three basic strategies in reducing drug and alcohol use are (a) avoid triggers or use them as cues for a new behavior chain pattern, (b) stop drug and alcohol thoughts, and (c) solve life problems related to use. Triggers are categorized as either external or internal. External triggers are situations or cues that lead to drug and alcohol thoughts. When youth recognize and identify external triggers, the triggers are then prioritized, and goals are set. The primary line of defense is to identify personal, external triggers, rank them in terms of importance, and design plans to avoid them.

The primary internal triggers for substance use that were dealt with in the intervention are negative feelings, depression, anxiety, and anger. Two cognitive and two behavioral strategies are employed. The two cognitive strategies for coping with a depression and substance use link are countering negative beliefs and reframing. The two behavioral strategies to cope with these triggers are distraction by initiating satisfying life activities and scheduling. In addition to negative feelings, drug and alcohol use are triggers for sex. Youth identify the negative consequences of mixing drugs, alcohol, and sex and practice resistance and negotiation skills with partners to abstain from combining drug and alcohol use with sex. For some people in the early stages of chronic substance use, sex is enhanced or anxiety about sex is reduced, thus reinforcing substance use as a means of sexual pleasure. Breaking the connection between substance use and sex is important in being able to avoid potential triggers in the future and has substantial benefits. However, as withdrawal from heavy drug use continues, there may be a temporary loss of interest in sex and sexual dysfunction, such as difficulties for men in becoming erect and for women in reaching orgasm. These losses can be devastating for some YLH and can interfere with their interest in staying drug-free. By acknowledging such typical behavioral routines in this module, YLH receive support to discontinue their risk acts.

The motivation to change behavior in Module 2 is protection from reinfection and altruism toward others. A desire to maintain health is addressed by mustering peer support and developing strong peer norms that endorse safer sex and abstinence from substance use. Module 2 also focuses on reducing sexual transmission, reinfection, and unwanted pregnancies. A number of ethical dilemmas are confronted by the youth in relation to sexual behavior. Examples of ethical issues include (a) wanting a baby at the risk of vertical transmission; (b) having unprotected sex with someone you love, and are monogamous with, but risk transmission; (c) telling a sexual partner you will not have sex without a condom; (d) disclosing your status when it might cause trouble in a relationship; and (e) refusing unprotected sex with a partner you are committed to but who insists on unprotected sex.

Several new skills related to reducing risk acts are addressed: (a) refusing drugs in a socially competent manner within a drug-using social network, (b) disclosing status to sexual partners, and (c) using condoms consistently over time. Disclosure of serostatus to present and past sexual partners is a critical public health strategy to stop the spread of infection. Socially competent scripts for disclosing this information and specific ways to avoid or control potentially violent encounters are utilized. Issues such as how true love sometimes becomes identified with having unprotected sex, in a self-destructive demonstration of loyalty, among couples with one HIV-positive partner is discussed.

Module 3: Maintaining safe acts and a healthy lifestyle

To live a healthy life with HIV, the youth must maintain changes in healthy daily routines; relationships with doctors, peers, and partners; shifting roles; and progression through stages of adaptation to positive serostatus. Integration of these changes is an even more difficult task to achieve. The third module helps YLH integrate the new behavioral patterns acquired in earlier sessions to recognize the link of daily actions to forming a person's identity.

The eight sessions of Module 3 focus on life satisfaction and emotional strength. Quality of life is explored in a number of ways: YLH learn to (a) identify a basic set of values that define one's personal identity as a YLH, reinforcing the identity formation discussions of Modules 1 and 2 regarding distancing one's sense of self from self-destructive behaviors; (b) reduce the negative emotional reactions (e.g., depression and anxiety) that can manifest as a result of living with their serostatus; (c) increase sense of self-control; (d) live fully in the moment; and (e) reduce motivations for self-destructive behavior, particularly substance use. YLH learn meditation as a means of developing an awareness of every moment in their life.

Successive Approximations to a New Identity

Because the framing of behavior change occurs within the context of social roles and identities, we would like to demonstrate how exercises in forming a new identity unfold across the sessions of each module. This intervention serves as a mechanism for achieving the behavioral goals of reducing the transmission of HIV, increasing adherence to medical regimens, and improving the quality of life of YLH. However, youth must explore and realize their identity as an HIV-positive person before they are able to attain these behavioral goals. A youth's view about who they are and how they fit into the world provides the cognitive structure by which their and other's behavior is interpreted. Therefore, before YLH can confront their own transmission behavior, they must deal with their own cognitions and attitudes about being HIV-positive. Their identity forms the basis for achieving behavioral goals. Consequently, the exercises in the intervention lead youth through a process of successive approximations to a new identity that will prepare them to accomplish behavioral goals.

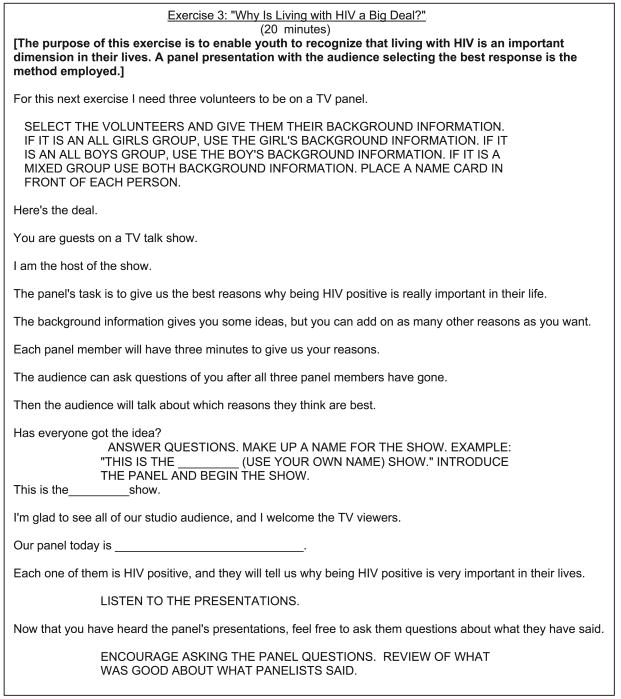

Table 2 outlines a series of exercises contained in the intervention that guides the youth through exploring personal identity as a person living with HIV. This exploration is the foundation for subsequently acquiring the skills necessary for the disclosure of serostatus to sexual partners. The first two sessions of the intervention are dedicated to the youth's exploration of personal attitudes about being HIV-positive and consideration of why being HIV-positive is important in their life (Figure 2). This discussion allows the youth to examine how they want to relate to other people and have others relate to them. In addition, youth prioritize their most important values and goals. After addressing positive attitudes toward HIV, youth practice arguing against negative self-statements, identify situations in their life that they want to improve, and develop long-term goals in multiple areas of their life. By addressing the broader concepts of enhancing the youth's skill to set personal life goals, the intervention moves the youth along the continuum of being able to gain and perform the skills necessary to accomplish behavioral goals.

TABLE 2. A Series of Exercises That Illustrate the Process of Successive Approximations to a New Identity for Youth Living With HIV (YLH).

| Behavioral Goal: Disclosure to Sexual Partners | ||

|---|---|---|

| Module | Session | Exercise |

| 1 | 1 | Confront attitudes toward being HIV-positive |

| 1 | 1 | Consider why being HIV-positive is important in your life |

| 1 | 3 | Feeling thermometer of script involving someone disclosing to a friend |

| 1 | 3 | Problem solve whether to tell |

| 1 | 3 | Identify situations where telling is necessary |

| 1 | 4 | Respond to stigma statements |

| 1 | 4 | Cognitive self-talk |

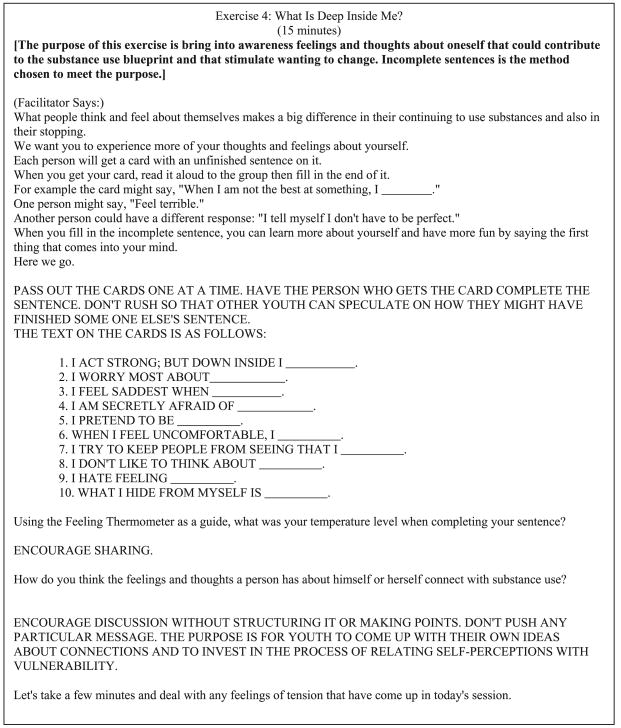

| 1 | 7 | Incomplete sentence exercise—how they feel about themselves and what emotions they're avoiding |

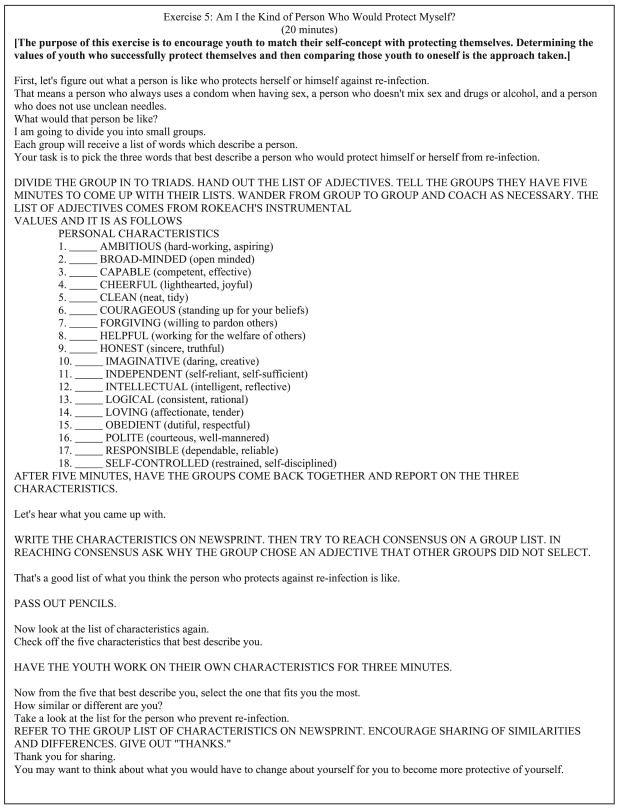

| 1 | 8 | Compare characteristics of people who successfully avoid reinfection with personal characteristics |

| 2 | 1 | Explore personal goals through identifying possible selves |

| 2 | 1 | Scripts to illustrate dilemmas around sexual issues for YLH |

| 2 | 3 | Session: Should I tell my partner I am HIV-positive? |

Figure 2. Module 1, Session 2.

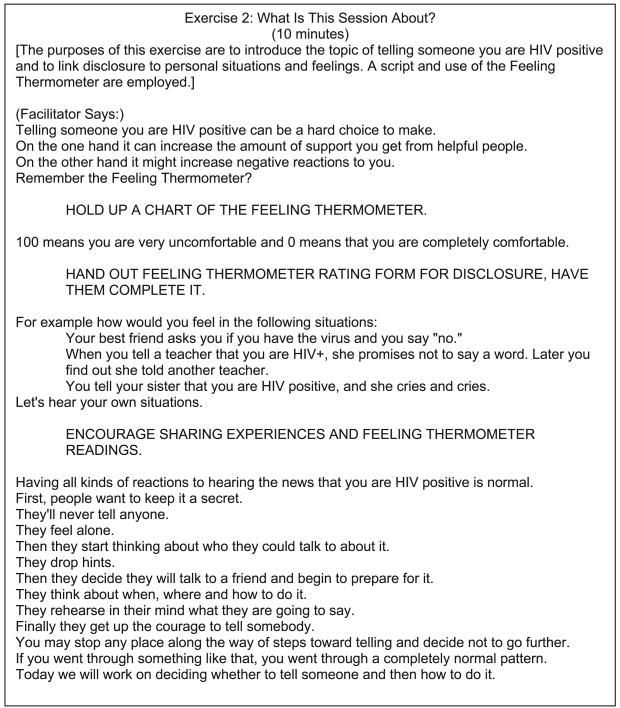

The third session of the intervention initiates an active discussion regarding disclosure. This session is not a comprehensive, in-depth discussion of disclosure. Rather, this session introduces the concept and helps the youth explore their feelings regarding disclosure—how their personal identity affects their decision to disclose and rehearsal of the skills necessary in making the decision about whether to disclose. A number of cognitive-behavioral tools are used to assist the youth in identifying feelings and recognizing the relationship between emotions and cognitions. The feeling thermometer is a primary tool used for increasing the youth's ability to label their feelings in situations of various levels of emotional intensity, describe and monitor the intensity of their feelings, and manage and self-control highly charged emotional reaction (Rotheram-Borus, 1988). As the exercise in Figure 3 shows, youth are given the opportunity to discuss the range of situations and feelings associated with disclosure.

Figure 3. Module 1, Session 3.

Session 3 also permits for rehearsal of the behavioral skills necessary for disclosure. Youth cannot choose to disclose if they lack the cognitive behavioral skills to enact disclosure behavior. This session addresses the short-term goals around disclosure issues: (a) to employ problem solving to make a decision about telling someone of their HIV-positive status and (b) to learn how to tell someone that they are HIV-positive. Links between feelings, actions, and thoughts form a plan for youth in disclosing their serostatus. The clarification, skill rehearsal, and plan formed in Session 3 are the foundation for more in-depth discussion and skills-building of the main behavioral goal of disclosure to sexual partners addressed in Module 2.

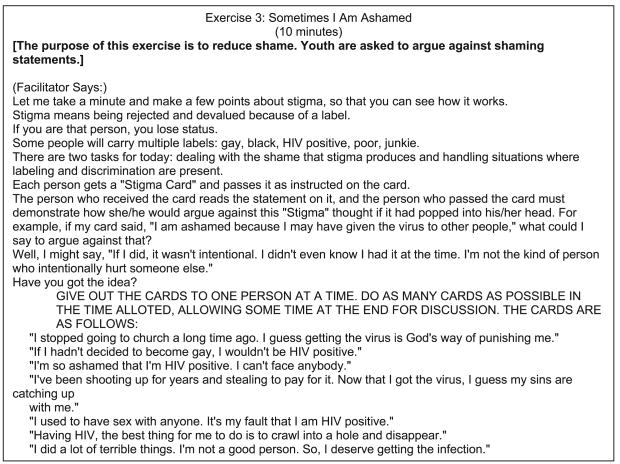

A key issue for YLH is coping with stigma. If internalized, stigma can result in low self-worth and lack of self-efficacy (Goffman, 1963). The consequence is a negative self-identity established by negative attitudes toward self, decreasing the youth's capacity to acquire skills to disclose. Therefore, coping with stigma from others is related to disclosure (Lee, Rotheram-Borus & O'Hara, 1999). To prepare youth for disclosure, confronting the youth's negative self-identity and stigma is an important step in the successive approximation process. In Session 4, youth are asked to (a) identify feelings of shame they have about their HIV seropositive status, (b) increase their skills in dealing with situations in which they are stigmatized, and (c) increase their ability to relax in tense situations. These tasks are accomplished through the use of the feeling thermometer, confronting negative beliefs, problem solving, and the use of cognitive self-talk. As Figure 4 illustrates, a common technique used in the intervention is challenging negative beliefs. In the illustrated exercise, youth are given a card with a statement outlining a negative belief and YLH then argue against that belief. These types of activities are important in assisting the youth to restructure their thoughts of themselves and creating an identity with which the youth is prepared to acquire the necessary behavioral skills for disclosing.

Figure 4. Module 1, Session 4.

Cognitive self-talk is also used throughout the intervention. The use of self-talk in Session 4 builds self-efficacy and allows the youth to self-regulate affect in stressful and volatile situations. The development of self-talk is fundamental for being able to disclose. Before, during, and after disclosure, youth will need to motivate, regulate, and reward themselves for success. Youth begin to develop the use of cognitive self-talk in stigma situations that they are likely to encounter.

As shown in Figure 5, during Session 7 youth are given the opportunity to examine how they view themselves and self-reward. An incomplete sentence exercise is used to bring awareness of feelings and thoughts about oneself. Through examining their own cognitions, youth are also exploring their identity. This exploration permits youth to identify how their own feelings and thoughts contribute to their behavior. Again, the examination of self-image issues is crucial in youth's ability to disclose. A youth who has a negative self-image is more likely to feel that a negative reaction to disclosure is inevitable or that they are unworthy of love, which leads to barriers to forming intimate relationships.

Figure 5. Module 1, Session 7.

Session 8 allows the youth to explore their identity and the relationship it has on their behavior (Figure 6). Exploration of self and identity are woven throughout the exercises in the intervention and are examined from different perspectives and in reference to different behaviors. This repetition in exploring the concept of identity reinforces the cognitive restructuring that takes place. Youth are guided to accept being HIV-positive into who they are and to form and foster altruistic behavior by protecting others. And through a positive self-image, youth can be motivated toward self-preservation.

Figure 6. Module 1, Session 8.

In Exercise 5 of Session 8, youth are encouraged to match their identity with protecting their behavior and protecting themselves. Determining the values of youth that successfully protect themselves and then comparing those values to one's behavior is the approach taken. This exercise encourages further exploration of identity and allows youth to think about the characteristics of an identity that they would like to possess.

All of the exercises form the foundation for the first three sessions of Module 2 in which the youth confronts the issue of disclosure. As outlined in Figure 7, disclosure is critical in reaching the aim of Module 2: reducing the transmission of HIV. The emphasis in these sessions is on increasing motivation to accomplish this objective through supporting a positive social identity. Youth examine how their ideal self would behave in situations with sexual and moral dilemmas. Youth are engaged in their ideal and possible selves in the domains of lover and friend. Additionally, youth confront the dilemmas that sexual situations for HIV-positive youth present. Scenes, scripts, and stories provide the real life situations around which these discussions take place. Moral reasoning about disclosure is approached directly, but in a way that encourages exploration that fosters responsibility rather than guilt or impulsivity. The discussion is framed in ways to reduce condemnation, with choice being the main theme in the decision-making process. By reinforcing the youth's choice, they become empowered to enact safer behaviors. Finally, much of the work around identity exploration has prepared the youth to make a decision regarding disclosure that reflects the positive identity that the intervention has fostered.

Figure 7. Module 2: Outline of Sessions 1 and 3.

Throughout the intervention, a successive approximation to a new identity is the foundation for the acquisition of the variety of skills needed to reduce transmission behavior. We have illustrated how identity clarification was the framework used in preparing the youth for disclosure behavior. This framework can be outlined for all of the behaviors targeted by the intervention and is the basis for motivation toward behavior change.

Intervention Outcomes

Module 1: Stay Healthy

In response to Module 1: Stay Healthy, the participants that attended the intervention (the attended intervention group) reported significant reductions in health symptoms, the distress associated with these symptoms, and feelings of anxiety; improvements in positive coping styles; and increases in health-related self-efficacy compared to the control group. Only 27% of the control group attended support groups compared to 63% of the intervention group. There were no significant differences in outcome expectancies, the number of health appointments missed, and the participation in psychotherapy across the groups. These findings indicate positive behavioral changes in response to the Module 1 intervention. Substance use and sex acts did not change.

Module 2: Act Safe

In response to Module 2, youth attended a mean of 7.6 sessions (Mdn = 8, SD = 3.2) from a possible 11 sessions. High ratings were obtained on liking the group and trusting the leaders (M = 4.3, on a scale ranging from 1 to 5). Youth who attended the Module 2 intervention indicated a 50% reduction in substance use based on a weighted index of the frequency of use and severity of the drug among those in the attended intervention group compared to stable levels of use in the control group. We also found significantly greater reductions in the number of sexual partners, seronegative partners, unprotected sexual risk acts, and the proportion of YLH reporting a high-risk pattern in the Attended Intervention Group compared to the Control Group. Almost all (80%) YLH disclosed their serostatus to their current partners, therefore, there were no significant differences between the two groups.

Module 3: Being Together

Module 3 was aimed at enhancing quality of life. Similar to the earlier modules, attendance was high among the Attended Intervention Group: 5.3 of 8 sessions (Mdn = 5, SD = 2.58) were attended. Significant reductions in mental health symptoms on the Brief Symptom Inventory and the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale were observed for the intervention group, compared to the control intervention. Significant differences on a measure of quality of life were related to the number of intervention sessions attended. Youth who attended more sessions had a better quality of life. Substance use and sex acts in response to Module 3 continue to be analyzed.

Also, there was little generalization of the effect of different components of the program: increases in health behaviors were not associated with reductions in substance use (Comulada, Swendeman, Rotheram-Borus, Mattes, & Weiss, 2003). This is similar to adults; HIV-positive men who continue high-risk sex report using illicit drugs as a stress-coping strategy (Robins et al., 1994).

Next Steps

How this intervention is delivered, which settings are most cost-effective in delivering interventions, and how to best document the process of improved risk behaviors are issues that need substantially more research. Although successful HIV-related interventions have been delivered in small groups, there are disadvantages to this format that must be addressed for YLH. Previous successful preventive HIV interventions for adolescents have been implemented in small groups (see review by Jemmott & Jemmott, 2000). Our intervention for YLH was delivered in a small group. A program with positive outcomes, however, will not be broadly disseminated if it is not replicable or feasible. About 30% of the youth did not attend any module of the intervention. This may have been due, in part, to the research design. Youth sometimes had to wait up to 4 months before a sufficient number of youth were recruited to start an intervention group. There were also two baseline interviews and a 3-month break between modules. The small-group format led some YLH to fear stigmatization of being seropositive (Herek & Capitanio, 1993). Anonymity and confidentiality were central issues for these youth, similar to gay men (Roffman et al., 1989). For others, issues related to scheduling reduced attendance; it was often difficult to find one time each week that youth who were working could attend groups. Overall, small groups can only be implemented in large AIDS epicenters where sufficient numbers of youth are available; thus, small groups were not feasible in cities with low incidence of HIV among adolescents. The group setting also presented the possibility that youth with histories of substantial risk acts could meet other youth using alcohol and drugs and engage in unprotected sexual acts; similar to negative findings for small-group interventions with conduct-disordered substance-abusing adolescents (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999). Given these experiences, alternative intervention strategies that are also likely to be successful, particularly strategies that can be disseminated to public health settings, are needed.

Anonymous telephone groups and individual sessions have been used previously to conduct effective HIV-related interventions with gay men (Roffman et al., 1989; Roffman, Beadnell, Ryan, & Downey, 1995; Roffman, Picciano, Wickizer, Bolan, & Ryan, 1998) and are currently being investigated as delivery strategies for YLH. These two alternative intervention modalities provide confidentiality, address scheduling problems, allow us to recruit sufficient numbers of youth, and reduce the possibility of youth engaging in negative behaviors with other YLH. Telephones have historically been effectively used for crisis hotline counseling (Schneidman, 1975) and assessment interviews (Carlin, Silberfeld, Deber, & Lowy, 1996), including assessments of HIV risk acts (Hickey, 1996). Telephone groups have been used historically for smoking prevention (Demers, Neale, Adams, Trembath, & Herman, 1990; Rimer et al., 1994), including relapse among pregnant women (Ershoff, Quinn, & Mullen, 1995) and outreach counseling for battered women (Rubin, 1991). Roffman and colleagues (1995, 1998) have demonstrated that gay men will participate in telephone intervention groups with significant reductions in risk acts over time. Our research team is successfully using anonymous telephone groups with parents living with AIDS, to encourage participation in an intervention (91% attendance). Telephone groups allow youth from Miami and Los Angeles to be in the same group, reduce waits for enrollment to form a group, allow anonymity, reduce transportation and scheduling problems, and reduce the chance of engaging in peer-induced negative behaviors. By providing workbooks for youth to supplement the telephone interactions, the majority of the content of the group interventions can be delivered to youth on the telephone. Telephone groups offer one potential alternative for successfully intervening with seropositive youth, particularly if youth live in rural settings or are, at times, too ill to attend interventions in person.

Individual sessions are a second alternative modality to small-group interventions; this modality can be implemented by a variety of paraprofessionals in a variety of settings (outpatient medical clinics, clinics for sexually transmitted diseases [STDs], primary health care clinics). Seroincidence has been reduced by providing individual counseling to serodiscordant couples (Padian, O'Brien, Chang, Glass, & Francis, 1993), and STDs may be lowered in individual sessions in clinics for persons with STDs (Rotheram-Borus, Lee, et al., 2001). Individual sessions allow us to tailor the content of the intervention to the risk profile of the youth; there are fewer scheduling problems and difficulties in attending later sessions after missing earlier sessions.

These alternative strategies can (a) reduce the burden associated with a research design and deliver the intervention in a manner consistent with HIV service delivery in public health settings, (b) use strategies previously demonstrated successful with adults that do not have the problems associated with scheduling and anonymity, (c) enhance generalizability of the results by conducting the program in multiple sites, and (d) increase feasibility by reducing the costs of delivering the intervention and utilizing existing public health models (i.e., individual sessions).

The demand for antiretrovirals in the United States exceeds access to the drugs. There are currently 100,000 people who may not be able to take advantage of antiretrovirals (Cox, 1996); more than $200 million will be needed to provide the antiretroviral therapy for those who are identified as infected (Cox, 1996). Currently, it is estimated that up to 50% of YLH may be receiving combination therapies, a figure considerably lower than existing data for adults (Gwadz et al., 1999). The intervention described in this article cost $467 to deliver for Module 1 and $513 for Module 2 (Lee, Leibowitz, & Rotheram-Borus, in press), confirming our intervention as cost-effective.

Summary

This cost-effective intervention builds on the major developmental task of adolescence identity formation to enable YLH to learn proactive, positive behaviors to prevent the transmission of HIV by decreasing high risky sexual behavior and substance use. Its modules are derived from what is known about adolescent developmental issues, substance use, sexual behavior, and behavioral change processes. The intervention has been successful in changing high-risk sex behaviors in YLH, and it can be readily adopted in public health settings via different delivery formats.

Acknowledgments

Authors' Note: This article was completed with the support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The work benefited from the assistance of health care providers and research staff in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Marguerita Lightfoot, An assistant research psychologist with the Center for Community Health, Neuropsychiatric Institute, University of California–Los Angeles.

Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus, Director of the Center for Community Health, Neuropsychiatric Institute, University of California–Los Angeles, and the codirector of the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services.

Norweeta G. Milburn, Center for Community Health, Neuropsychiatric Institute, University of California–Los Angeles, and the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services

Dallas Swendeman, Center for Community Health, Neuropsychiatric Institute, University of California–Los Angeles.

References

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Kinder BN. Life skills training: A psychoeducational approach to substance-abuse prevention. In: Maher CA, Zins JE, editors. Pergamon general psychology series: Psychoeducational interventions in the schools: Methods and procedures for enhancing student competence. Vol. 150. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon; 1987. pp. 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Carlin K, Silberfeld M, Deber RB, Lowy F. Competency assessments: Perceptions at follow-up. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;41:167–174. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS/Risk reduction model (ARRM) Health Education Quarterly. 1990;17:53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessing the effectiveness of disease and injury prevention programs: Cost and consequences. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1995;44:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1998 guidelines for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 1998;47:1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Young people at risk—Epidemic shifts further toward young women and minorities. Atlanta, GA: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 2000a Retrieved in October 2001 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasr1202.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance supplemental report: HIV/AIDS in urban and nonurban areas of the United States. 2000b Retrieved in October 2001 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasrsupp62.htm.

- Chow R, Chin T, Fong IW, Bendayan R. Medication use patterns in HIV-positive patients. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 1993;46(4):171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comulada WS, Swendeman DT, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mattes KM, Weiss RE. Use of HAART among young people living with HIV. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:389–400. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S. The active voice. Washington, DC: National Association of People with AIDS; 1996. Autumn. AIDS drug assistance program in crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Demers RY, Neale AV, Adams R, Trembath C, Herman SC. The impact of physicians'brief smoking cessation counseling: A MIRNET study. Journal of Family Practice. 1990;31:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm. Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, McCoy CB, Word C, Serrano Y, et al. Intersecting epidemics: Crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331:1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ershoff DH, Quinn VP, Mullen PD. Relapse prevention among women who stop smoking early in pregnancy: A randomized clinical trial of a self-help intervention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1995;11:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. American Psychologist. 1991;46:931–946. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Hook RJ, Friman PC, Rapoff MA, Christophersen ER. The overestimation of adherence to pediatric medical regimens. Childrens Health Care. 1993;22:297–304. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc2204_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein DH, Reuland M. Psychological correlates of frequency and type of drug use among jail inmates. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:583–598. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman IM, Litt IF. Promoting adolescents' compliance with therapeutic regimens. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 1986;33:955–973. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Wiebel WW, Jose B, Levin L. Changing the culture of risk. In: Brown BS, Beschner GM, editors. Handbook on risk of AIDS: Injection drug users and sexual partners. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1993. pp. 499–516. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LN, Williams MT, Singh TP, Frieden TR. Tuberculosis, AIDS, and death among substance abusers on welfare in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334:828–833. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz M, De Vogli R, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Diaz M, Cisek T, James NB, et al. Behavioral practices regarding combination therapies for HIV/AIDS. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 1999;24:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP. Public reactions to AIDS in the United States: A second decade of stigma. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:574–577. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.4.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey DE. Voices. In: Nokes KM, editor. HIV/AIDS and the older adult. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1996. pp. 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS. HIV risk reduction behavioral interventions with heterosexual adolescents. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl. 2):S40–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. HIV prevention among adolescents. Paper presented at the 104th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 1996. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Greenberg J, Abel GG. HIV-seropositive men who engage in high-risk behaviour: Psychological characteristics and implications for prevention. AIDS Care. 1997;9:441–450. doi: 10.1080/09540129750124984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr GR, Koob JJ, Morgan MG, Kalichman SC, et al. Factors associated with severity of depression and high risk sexual behavior among persons diagnosed with HIV infection. Health Psychology. 1993;12:215–219. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Betts R, Brasfield TL, Hood H. A skills-training group intervention model to assist persons in reducing risk behaviors for HIV infection. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1990;2:24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Making condoms available in schools. The evidence is not conclusive. Western Journal of Medicine. 2000;172:149–151. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D, Short L, Collins J, Rugg D, Kolbe L, Howard M, et al. School-based programs to reduce sexual risk behaviors: A review of effectiveness. Public Health Reports. 1994;109:339–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Leibowitz A, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Cost-effectiveness of a behavioral intervention for seropositive youth. AIDS Education and Prevention. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.3.105.62906. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Challenges associated with increased survival among parents living with HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1303–1309. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, O'Hara P. Disclosure of serostatus among youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Preventing drug use among children and adolescents: A research-based guide (No 97-4212) Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Padian NS, O'Brien TR, Chang Y, Glass S, Francis DP. Prevention of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus through couple counseling. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1993;6:1043–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer BK, Orleans CT, Fleisher L, Cristinzio S, Resch N, Telepchak J, et al. Does tailoring matter? The impact of a tailored guide on ratings and short-term smoking-related outcomes for older smokers. Health Education Research. 1994;9:69–84. doi: 10.1093/her/9.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins AG, Dew MA, Davidson S, Penkower L, Becker JT, Kingsley L. Psychological factors associated with risky sexual behavior among HIV-seropositive gay men. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1994;6:483–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffman RA, Beadnell B, Ryan R, Downey L. Telephone group counseling in reducing AIDS risk in gay and bisexual males. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 1995;2:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Roffman RA, Gordon JR, Beadnell BA, Stern MJ, Fisher D, Simpson D, et al. Reaching gay and bisexual men who continue to engage in unsafe sexual activity: A comparison of subjects recruited for in-person or telephone counseling formats. Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Washington, DC. 1989. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Roffman RA, Picciano JF, Wickizer L, Bolan M, Ryan R. Anonymous enrollment in AIDS prevention telephone group counseling: Facilitating the participation of gay and bisexual men. Journal of Social Services Research. 1998;23:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ. Assertiveness training with children. In: Price RH, Cowen EL, Lorion RP, Ramos-McKay J, editors. Fourteen ounces of prevention: A casebook for practitioners. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1988. pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Futterman D. Promoting early detection of HIV among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154:435–439. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.5.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum J Teens Linked to Care Consortium. Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youth living with HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee M, Zhou S, O'Hara P, Birnbaum JM, Swendeman D, Wright RG, et al. Variation in health and risk behaviors among youth living with HIV. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;13:42–54. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.1.42.18923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Miller S. Secondary prevention for youths living with HIV. AIDS Care. 1998;10:17–34. doi: 10.1080/713612347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Swendeman D, Chao B, Chabon B, Zhou S, et al. Substance use and its relationship to depression, anxiety, and isolation among youth living with HIV. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;6:293–231. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0604_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Wight R, Lee MB, Lightfoot M, Swendeman D, et al. Improving quality of life among young people living with HIV. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2001;24:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, O'Keefe Z, Kracker R, Foo HH. Prevention of HIV among adolescents. Prevention Science. 2000;1:15–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1010071932238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Song J, Gwadz M, Lee MB, Van Rossem R, Koopman C. Reductions in HIV risk among runaway youth. Prevention Science. 2003;4:179–188. doi: 10.1023/a:1024697706033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A. The effectiveness of outreach counseling and support groups for battered women: A preliminary evaluation. Research on Social Work Practice. 1991;1:332–357. [Google Scholar]

- Schneidman E. Perturbation and lethality as precursors of suicide. Life Threatening Behavior. 1975;1:23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Spivack G, Platt G, Shure M. A problem solving approach to adjustment. New York: Jossey-Boss; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Stricof RL, Kennedy JT, Nattell TC, Weisfuse IB, Novick LF. HIV seroprevalence in a facility for runaway and homeless adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(Suppl):50–53. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.suppl.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UCLA Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services. Choosing life: Empowerment, actions, results intervention manual. 1999 Retrieved in October 2001 from http://chipts.ucla.edu/pdf/manuals/clear_individual/ClearM3S3_Indiv.PDF.

- UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDS epidemic update: December 1998. 1998 Retrieved in October 2001 from http://www.unaids.org.

- Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, Levine WC. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:883–888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]