Abstract

Background

The liver plays a central role in nutrient and xenobiotic metabolism, but its functionality declines with age. Senior dogs suffer from many of the chronic hepatic diseases as elderly humans, with age-related alterations in liver function influenced by diet. However, a large-scale molecular analysis of the liver tissue as affected by age and diet has not been reported in dogs.

Methodology/Principal Findings

Liver tissue samples were collected from six senior (12-year old) and six young adult (1-year old) female beagles fed an animal protein-based diet (APB) or a plant protein-based diet (PPB) for 12 months. Total RNA in the liver tissue was extracted and hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip® Canine Genome Arrays. Using a 2.0-fold cutoff and false discovery rate <0.10, our results indicated that expression of 234 genes was altered by age, while 137 genes were differentially expressed by diet. Based on functional classification, genes affected by age and/or diet were involved in cellular development, nutrient metabolism, and signal transduction. In general, gene expression suggested that senior dogs had an increased risk of the progression of liver disease and dysfunction, as observed in aged humans and rodents. In particular for aged liver, genes related to inflammation, oxidative stress, and glycolysis were up-regulated, whereas genes related to regeneration, xenobiotic metabolism, and cholesterol trafficking were down-regulated. Diet-associated changes in gene expression were more common in young adult dogs (33 genes) as compared to senior dogs (3 genes).

Conclusion

Our results provide molecular insight pertaining to the aged canine liver and its predisposition to disease and abnormalities. Therefore, our data may aid in future research pertaining to age-associated alterations in hepatic function or identification of potential targets for nutritional management as a means to decrease incidence of age-dependent liver dysfunction.

Introduction

The liver is the central organ in the regulation of nutrient metabolism, xenobiotic metabolism, and detoxification. Evidence from humans and rodents has indicated that aging leads to a marked change in the liver structure and function [1]. In general, aged liver is characterized by a decline in weight, blood flow, regeneration rate, and detoxification, which have been related to an increased risk of liver abnormalities in the elderly [1]. Moreover, age-associated changes in liver function are expected to be affected by diet because dietary nutrient metabolism is centered in the liver. However, molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of age and diet on liver physiology and pathogenesis remain inconclusive.

Recent advances in microarray technology and bioinformatics allow the analysis of genome-wide gene expression changes, providing a useful link between complex molecular events and physiological responses by identifying specific genes and metabolic pathways involved [2]. Although senior dogs suffer from many of the chronic diseases present in the elderly [3], molecular analyses of canine tissues have been rarely performed. To our knowledge, no data pertaining to a large-scale molecular analysis of the liver tissue in senior vs. young adult dogs have been reported.

As a starting point, our laboratory performed an experiment designed to measure physiological response of healthy adult dogs as a function of age and diet [4]. Young adult or senior dogs were fed either an animal protein-based diet (APB) containing high dietary fat and low fiber or a plant protein-based diet (PPB) containing moderate fat and high fiber. We found that the diet altered nutrient digestibility, blood chemistry, gastrointestinal morphology, and microbial fermentation, with the effects being dependent on age [4], [5]. In previous publications, we reported the effects of age and diet on gene expression alterations in cerebral cortex [6], adipose tissue [7], and skeletal muscle [8] of the dogs that were used by Swanson et al. [4]. In the current experiment, total RNA was isolated from the liver tissue collected from our previous experiment [4], comparing hepatic gene expression profiles as a function of age and diet using commercial canine microarrays. Given the fact that the liver plays a central role in nutrient metabolism and its functionality declines with age, it was hypothesized that hepatic gene expression would be largely dysregulated in senior vs. young adult dogs and this impairment would be exacerbated by feeding APB diet containing animal-derived lipids high in saturated fatty acids and cholesterol.

Results

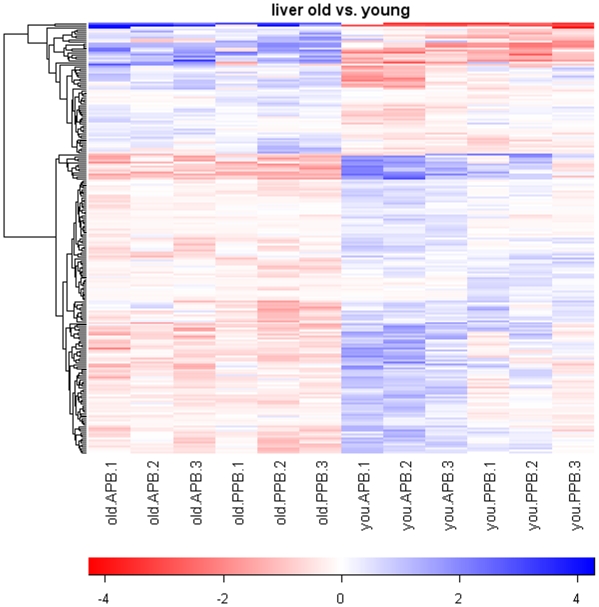

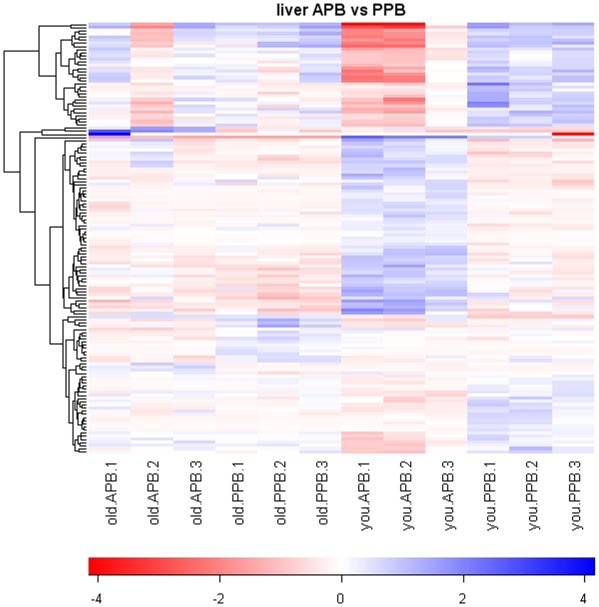

Based on a 2.0-fold change cutoff and FDR <0.10, a total of 371 gene transcripts were differentially expressed by age (234 genes) and/or diet (137 genes), according to the pre-planned statistical screening methods (Table 1). The heat map in Figure 1 indicates significant and consistent gene expression changes due to age, and within age groups dietary treatment had a greater impact on gene expression changes in young dogs than in senior dogs. However, when genes altered by diet were clustered, inconsistent pattern was observed (Figure 2). Following removal of unannotated genes and duplicate probe sets of the same gene, 89 genes were identified as being differentially expressed by age (53 genes) and/or diet (36 genes). Twenty five genes were up-regulated (Tables 2 and 3) and 28 genes were down-regulated (Tables 4 and 5) with increased age. Nine genes were up-regulated (Table 6) and 27 genes were down-regulated (Tables 7 and 8) in dogs fed the APB vs. PPB diet.

Table 1. Global view of liver gene expression alterations in senior vs. young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based diet (APB) or plant protein-based diet (PPB).

| Number of gene transcripts altered1 | Number of annotated genes altered2 | |

| Total genes differentially expressed | 371 (2.7%) | 89 |

| Age-associated alterations | 234 (1.7%) | 53 |

| Up-regulated | 76 | 25 |

| Down-regulated | 158 | 28 |

| Diet-associated alterations | 137 (1.0%) | 36 |

| Up-regulated | 65 | 9 |

| Down-regulated | 72 | 27 |

Values in the parenthesis represent the percentage of gene transcripts differentially expressed in relation to the total number of genes expressed in the liver tissue (13,778 genes).

Number of annotated and non-redundant genes that had >2.0 fold-change in gene expression.

Figure 1. Heatmap of senior vs. young adult dog pairwise comparisons.

Values are the GCRMA-processed probe set value (Log2 scale) minus the mean value for that probe set across all arrays. The dendrogram was created by hierarchical cluster analysis.

Figure 2. Heatmap of animal-protein based diet (APB) vs. plant-protein based diet (PPB) pairwise comparisons.

Values are the GCRMA-processed probe set value (Log2 scale) minus the mean value for that probe set across all arrays. The dendrogram was created by hierarchical cluster analysis.

Table 2. Up-regulated cell growth and development-, cellular metabolism-, and cell signaling and signal transduction-associated genes in hepatic tissue of senior vs. young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) or plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Fold Change | ||||

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | APB | PPB |

| Cell growth and development | ||||

| Tumor marker | WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 | WFDC2 | 107.0 | 21.97 |

| Cell adhesion | CD99 molecule | CD99 | 3.17 | |

| p53 in cell cycle arrest | G-2 and S-phase expressed 1 | GTSE1 | 2.24 | |

| Cellular metabolism | ||||

| Amino acid metabolism | D-amino-acid oxidase | DAO | 2.67 | |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | Phosphofructokinase | PFKP | 4.27 | |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase3 | PFKFB3 | 3.10 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Fatty acid desaturase 3 | FADS3 | 4.91 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Retinol dehydrogenase 16 | RDH16 | 2.38 | |

| Glycolipid synthetic process | Forssman glycolipid synthetase (FS) | GBGT1 | 3.59 | 4.49 |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | Hydroxyacid oxidase 2 | HAO2 | 2.12 | |

| Xenobiotic metabolism (detoxification) | Glutathione S-transferase, pi 1 | GSTP1 | 4.41 | 12.60 |

| Xenobiotic metabolism | Carboxylesterase 2 | CES2 | 3.87 | |

| Cell signaling and signal transduction | ||||

| RAS signaling pathway | RAS guanyl releasing protein 1 | RASGRP1 | 2.63 | |

Table 3. Up-regulated cellular trafficking and protein processing-, immune and stress response-, and transcription-translation-associated genes in hepatic tissue of senior vs. young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) or plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Fold Change | ||||

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | APB | PPB |

| Cellular trafficking and protein processing | ||||

| Transmembrane transport | Peroxisomal membrane protein 69 | ABCD4 | 3.13 | |

| Synaptic transmission | Synaptophysin-like 1 | SYPL1 | 2.11 | |

| Protein ubiquitination | Ubiquitin-like 1 activating enzyme E1A | SAE1 | 2.27 | |

| Immune and stress response | ||||

| Immune response | Galectin-2 | LGALS2 | 2.07 | |

| Immune response | Ig heavy chain V-III region VH26 precursor | LOC607467 | 9.66 | |

| Transcription-translation | ||||

| Transcription | Ribosomal protein L6 | RPL6 | 3.53 | |

| Telomere maintenance | Telomeric repeat binding factor 2 interacting protein 1 | TERF2IP | 2.73 | |

| Miscellaneous and unknown | ||||

| Muscle growth | Musculoskeletal, embryonic nuclear protein 1 | MUSTN1 | 64.66 | |

| Calcium channel activity | Glycoprotein M6A | GPM6A | 8.73 | 8.32 |

| Fibrinolysis | Annexin A2 | ANXA2 | 7.82 | |

| Unknown | FUN14 domain containing 2 | FUNDC2 | 2.45 | |

| Unknown | Transmembrane 6 superfamily member 1 | TM6SF1 | 3.82 | |

Table 4. Down-regulated cell growth and development-, cellular metabolism-, and cell signaling and signal transduction-associated genes in hepatic tissue of senior vs. young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) or plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Fold Change | ||||

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | APB | PPB |

| Cell growth and development | ||||

| Cell adhesion | Coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor | CXADR | −2.69 | |

| Cytoskeleton organization | Erythrocyte surface protein band 4.1 | EPB41 | −2.25 | |

| Cell cycle | DIP13 beta | APPL2 | −2.40 | |

| Cellular metabolism | ||||

| ATP synthesis | ATPase II | ATP8A1 | −4.22 | |

| Glycogen metabolism | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3 beta) | GSK3B | −2.26 | |

| AA metabolism | Asparagine synthetase domain containing 1 | ASNSD1 | −2.00 | |

| Tryptophan metabolism (catabolism) | Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase | KMO | −2.48 | |

| Cholesterol homeostasis | Niemann-Pick disease, type C1 | NPC1 | −2.05 | |

| Xenobiotic metabolism | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide B15 | UGT2B15 | −3.30 | |

| Aldehyde metabolism | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A1 | ALDH1A1 | −2.29 | |

| Cell signaling and signal transduction | ||||

| TGF-β signaling pathway | Follistatin | FST | −5.39 | −3.73 |

| TGF-β signaling pathway | Thrombospondin 1 precursor | THBS1 | −4.28 | |

| Androgen receptor signaling pathway | Nuclear receptor coactivator 2 | NCOA2 | −4.08 | −3.00 |

| Phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway | Inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase (IPPase) (IPP) | INPP1 | −3.05 | |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor signaling pathway | Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor alpha | LIFR | −2.39 | |

Table 5. Down-regulated cellular trafficking and protein processing-, immune and stress response-, and transcription-translation-associated genes in hepatic tissue of senior vs. young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) or plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Fold Change | ||||

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | APB | PPB |

| Cellular trafficking and protein processing | ||||

| Endoplasmic reticulum organization | Atlastin GTPase | ATL2 | −2.92 | |

| Transport | Golgi phosphoprotein 4 | GOLIM4 | −3.63 | |

| Protein transport | Solute carrier family 15 (H+/peptide transporter) | SLC15A2 | −3.22 | |

| Protein transport | Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis protein 2 | RIMS2 | −3.03 | |

| Proteolysis | Nardilysin precursor (N-arginine dibasic convertase) | NRD1 | −2.13 | |

| Ion transport | Six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 2 | STEAP2 | −2.67 | |

| Immune and stress response | ||||

| Immune response | Galectin 8 | LGALS8 | −4.56 | |

| Immune response | IgA heavy chain constant region | IGHAC | −4.24 | |

| Transcription-translation | ||||

| Transcription | CG32045-PB, isoform B | FRY | −5.06 | |

| Translation | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E type 3 | LOC611215 | −3.01 | |

| Histone acetylation | Enhancer of polycomb homolog 1 isoform 2 | EPC1 | −2.45 | |

| Miscellaneous and unknown | ||||

| Unknown | Spermatogenesis associated, serine-rich 2 | SPATS2 | −2.13 | |

| Unknown | CG7020-PA | DIP2B | −2.19 | |

Table 6. Up-regulated genes in hepatic tissue of senior and young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) vs. plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Fold Change | ||||

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | Senior | Young |

| Cell growth and development | ||||

| Cytoskeleton organization | PDZ and LIM domain 3 | PDLIM3 | 3.08 | |

| Cytoskeleton organization | Erythrocyte surface protein band 4.1 | EPB41 | 2.07 | |

| Cellular metabolism | ||||

| Tetrahydrofolate metabolism | Pipecolic acid oxidase | PIPOX | 2.10 | |

| Aldehyde metabolism | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A1 | ALDH1A1 | 2.18 | |

| Cell signaling and signal transduction | ||||

| G-protein mediated signal pathway | Regulator of G-protein signaling 10 (RGS10) | RGS10 | 2.39 | |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor signaling pathway | Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor alpha | LIFR | 2.06 | |

| Cellular trafficking and protein processing | ||||

| Protein transport | Golgi phosphoprotein 4 | GOLIM4 | 3.47 | |

| Protein transport | Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis protein 2 | RIMS2 | 2.52 | |

| Miscellaneous and unknown | ||||

| Unknown | CG7020-PA | DIP2B | 2.15 | |

Table 7. Down-regulated cell growth and development-, cellular metabolism-, and immune and stress response-associated genes in hepatic tissue of senior and young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) vs. plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Fold Change | ||||

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | Senior | Young |

| Cell growth and development | ||||

| Tumor suppressor | Major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2A | MFSD2A | −2.53 | |

| Autophagy | Autophagy protein 12-like (APG12-like) (ATG12) | ATG12 | −4.73 | |

| Cell cycle | Cell cycle associated protein 1 | CAPRIN1 | −4.17 | |

| Cell cycle | Retinoblastoma binding protein 4 | RBBP4 | −3.74 | |

| Cell death | TAR DNA binding protein isoform 4 | TARDBP | −2.22 | |

| Cellular metabolism | ||||

| ATP synthesis | ATP synthase gamma chain, mitochondrial | ATP5C1 | −4.73 | |

| AA metabolism | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase E1 component beta chain | BCKDHB | −3.72 | |

| CHO metabolism | Pyruvate dehydrogenase protein X component, mitochondrial precursor | PDHX | −2.38 | |

| Lipid metabolism | N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase (acid ceramidase) 1 | ASAH1 | −10.63 | |

| Glucocorticoid metabolism | Hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 1 | HSD11B1 | −4.69 | |

| O-linked glycosylation | GalNAc transferase 13 | GalNAc-T13 | −2.05 | |

| Xenobiotic metabolism | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2A1 precursor, microsomal | UGT2A1 | −4.15 | |

| Immune and stress response | ||||

| Immune response | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 2 | ENPP2 | −2.82 | |

| Oxidative stress | Superoxide dismutase [Mn], mitochondrial precursor | SOD2 | −2.22 | |

| Oxidative stress | Catalase | CAT | −2.22 | |

Table 8. Down-regulated cell signaling and signal transduction-, cellular trafficking and protein processing-, and transcription-translation-associated genes in hepatic tissue of young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) vs. plant protein-based (PPB) diet.

| Functional classification | Gene name | Symbol | Fold Change |

| Cell signaling and signal transduction | |||

| Neurotropin signaling pathway | Mitochondrial import stimulation factor L subunit | YWHAE | −16.21 |

| Hepatocyte growth factor receptor signaling pathway | Met proto-oncogene (hepatocyte growth factor receptor) | MET | −3.33 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | Ras-like protein TC25 | RAC1 | −3.65 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | Calcineurin A2 | PPP3CB | −2.42 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | HMG-box transcription factor 1 | HBP1 | −2.16 |

| Cellular trafficking and protein processing | |||

| Transport | Synaptophysin-like 1 isoform b | SYPL1 | −2.26 |

| Protein secretion | Protein disulfide-isomerase A4 | PDIA4 | −5.35 |

| Protein transport | Ras-related protein Rab-18 | RAB18 | −4.37 |

| Protein binding | Multiple PDZ domain protein | MPDZ | −3.10 |

| Protein binding | TIP41, TOR signaling pathway regulator-like | TIPRL | −2.55 |

| Transcription-translation | |||

| Transcription | Mediator complex subunit 28 | MED28 | −4.72 |

| Telomere maintenance | Telomeric repeat binding factor 2 interacting protein 1 | TERF2IP | −3.26 |

For validation of microarray data, 5 genes (WFDC2, PFKP, FADS3, GBGT1, and NCOA2) identified to be differentially expressed by age in microarray analysis were selected and validated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) according to methods described previously [9]. Although the magnitude of fold change by microarray vs. qRT-PCR was variable, the direction in gene expression change was identical between the 2 methods (data not shown).

Hepatic lipid composition is presented in Table 9. Senior dogs had greater (P<0.01) concentrations of total lipids and total monounsaturated fatty acids and had a tendency for greater concentrations of total saturated fatty acids (P = 0.09) and total polyunsaturated fatty acids (P = 0.06) as compared to young adult dogs. Despite differences in diet composition and diet-associated blood cholesterol changes as observed in our previous experiment [4], however, diet did not alter hepatic lipid composition in either senior or young adult dogs. No significant interaction between age and diet was observed for hepatic lipid composition.

Table 9. Hepatic lipid composition in senior vs. young adult dogs fed an animal protein-based (APB) or plant protein-based (PPB) diet1.

| Senior dogs | Young dogs | P – value2 | |||||

| Lipid compositions | APB | PPB | APB | PPB | SEM | Age | Diet |

| Total lipids | 178.2 | 157.8 | 120.6 | 114.7 | 10.80 | <0.01 | 0.26 |

| Total SAT | 100.5 | 94.9 | 85.3 | 81.2 | 7.38 | 0.09 | 0.53 |

| Total MUFA | 64.7 | 52.7 | 31.5 | 29.0 | 5.76 | <0.01 | 0.24 |

| Total PUFA | 13.0 | 10.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.40 | 0.06 | 0.76 |

Values for lipid concentrations are presented as mg/g DM of tissue (n = 3 per treatment).

No age×diet interactions were significant (P>0.05).

Discussion

Global alterations in gene expression due to age and diet

Of the 13,778 genes expressed in liver tissue, 1.7% (234/13,778) of gene transcripts were differentially expressed by age, while 1.0% (137/13,778) of gene transcripts were altered by diet in this experiment. This observation that a relatively small number of genes was altered by age and diet in these dogs is in agreement with our previous microarray data for cerebral cortex [6], abdominal adipose [7], and skeletal muscle [8] tissues of the same dogs. Therefore, it may be implicated that physiological alteration in the liver due to age and diet, as reported in other body tissues, is likely achieved by a small number of genes and their transcriptional alterations [10]. Age*diet interactions appeared to be present because age-associated gene expression changes in the liver were more common in dogs fed APB (38 genes) than for dogs fed PPB (21 genes). We speculate that because APB had a greater concentration of protein and lipid than PPB, it put more pressure on the liver to metabolize dietary protein and lipids.

Age-associated alterations in gene expression

The WAP four-disulfide core domain 2 (WFDC2) was greatly up-regulated in senior dogs consuming APB (107.0 fold) or PPB (21.97 fold) in this experiment. The up-regulation of WFDC2 gene has been considered an early biomarker for carcinogenesis, especially for ovarian and pancreatic cancers [11]. It has also been reported that WFDC2 is involved in inflammatory responses and host defense, and its activity is increased in chronically inflamed lungs with cystic fibrosis [12]. Increased expression of genes related to inflammation and immune response was also observed in other tissues from these dogs [6], [7], [8]. In our previous experiment [4], senior dogs fed APB had a greater concentration of blood cholesterol than those fed PPB diet. Increased blood cholesterol concentration has been related to an increased risk of liver inflammation and cystic fibrosis [13]. This may explain why the magnitude of change in WFDC2 gene expression was greater in senior dogs fed APB as compared to those fed PPB. Although physiological significance of WFDC2 in the liver has yet to be identified and dogs used in this experiment were all clinically healthy, it may be worthy to study this gene as a potential biomarker for the progression of liver dysfunction.

Several genes associated with cellular metabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids, or xenobiotics were affected by age. The up-regulation (2.67 fold) of the D-amino acid oxidase (DAO) gene in senior dogs agrees with previous results of increased DAO activity in the liver of aged rats [14]. This response has been hypothesized to be due to an increased need for detoxification of D-amino acids that may accumulate during aging [14]. The expression of kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO), a key enzyme associated with tryptophan catabolism, was down-regulated (2.48 fold) in senior dogs fed PPB. Age-associated decline in KMO activity was also reported in the rat liver [15]. It is suggested that decreased nicotinic acid synthesis as a result of disturbed tryptophan (kynurenine) catabolism with age may be a reason for age-associated abnormalities (e.g., impaired glucose tolerance) in the liver and other body organs [15].

Genes associated with the glycolytic pathway were differentially expressed in this experiment. Expression of phosphofructokinase (PFKP), which plays a role in the glycolytic flux as the first committed step of glycolysis [16], was up-regulated (4.27 fold) in the liver of senior dogs fed PPB. Moreover, 6-phosphfructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), which converts fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate [16], was also up-regulated (3.10 fold) in the liver of senior dogs fed PPB. Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate is a strong allosteric activator of PFKP to increase the rate of glycolysis, whereas it inhibits gluconeogenesis by decreasing activity of fructose-1,6-bisphophatase [16]. Moreover, increased concentrations of intracellular ATP are known to allosterically inhibit activity of PFKP [16]. We observed that the aged liver had a down-regulation (4.22 fold) of ATPase (ATP8A1) gene related to ATP synthesis. Overall, these observations suggest that hepatic glycolytic activity increases but gluconeogenic activity decreases in aged dogs and, therefore, possibly decreased hepatic glucose concentrations. Although it was not measured in this experiment, a reduction in hepatic glucose concentrations has been observed in aged mice [17]. Given the fact that liver is an important regulator of blood glucose concentrations, therefore, our observation in senior dogs suggests that aged liver may have a decreased capacity to maintain blood glucose homeostasis.

The down-regulation (2.26 fold) of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta gene (GSK3B), which is known to inactivate glycogen synthase [18], in senior dogs fed APB may reflect increased rate of glycogenesis in the aged liver. To our knowledge, however, increased glycogen synthesis or storage in the liver of aged individuals has not been reported, while a decrease in age-related hepatic glycogen storage was observed in aged mice [17]. Apart from its role in glycogen metabolism, it has been reported that hepatic expression of GSK3B declines with age in mice and this reduction is responsible for decreased regenerative ability of aged liver [19]. Therefore, decreased expression of GSK3B observed in this experiment may be more associated with a reduction in regenerative capacity of the liver rather than an increase in hepatic glycogen synthesis in senior dogs.

Senior dogs had greater amounts of hepatic total lipids, saturated fatty acids, and unsaturated fatty acids as compared to young adult dogs. This result was expected because increased hepatic lipid accumulation with age in humans and animals is a well known phenomenon [20], [21]. This response has been frequently associated with an increased risk of age-dependent liver diseases [22]. However, only a small number of genes (FADS3, RDH16, GBGT1, NPC1) involved in hepatic lipid metabolism were differentially expressed by age in this experiment.

Increased expression (4.91 fold) of fatty acid desaturase 3 (FADS3) in the aged liver may indicate the possibility of increased activity of de novo lipogenesis, although the liver is not the major de novo lipogenic organ in dogs [23]. It can be assumed that increased hepatic glycolytic activity observed in this experiment may accelerate the synthesis of citrate, the precursor for fatty acids and cholesterol biosynthesis [24], [25]. As a result, the activity of FADS3, which converts saturated fatty acids as the major end-products of de novo lipogenesis to monounsaturated fatty acids (e.g., oleic acids) as a main storage form in triglycerides [26], is expected to be increased. This may also explain why senior dogs had greater concentrations of hepatic lipids and monounsaturated fatty acids than young adult dogs.

The down-regulation (2.05 fold) of Niemann-Pick disease type C1 (NPC1), as observed in senior dogs consuming APB, may also contribute to increased hepatic lipid concentrations in the aged dogs. The NPC1 gene plays a role in the regulation of intracellular cholesterol trafficking and homeostasis, with its defect leading to an abnormal accumulation of cholesterol and other lipids in hepatic cells [27]. Although hepatic cholesterol concentrations were not measured in this experiment, increased blood cholesterol concentrations were observed in senior dogs [4]. Therefore, age-associated change in NPC1 expression and its effects on hepatic cholesterol concentrations may be a useful measure in future aging studies. Interestingly, Forssman glycolipid synthetase (GBGT1) gene related to Forssman glycolipid biosynthesis was up-regulated in senior dogs consuming APB (3.59 fold) or PPB (4.49 fold). It has been reported that increased expression of GBGT1 reduces the susceptibility to microbial toxins (e.g., Shiga toxins) because Forssman glycolipids, which do not bind microbial toxins, are thought to inhibit the binding of toxin by replacing toxin-binding glycolipid [28]. It is not clear why aged canine liver had increased expression of GBGT1 gene, but deserves attention in future experiments.

In mammals, the liver is the central organ for xenobiotic metabolism. It is well-known that the ability to detoxify xenobiotics in the liver declines with age [1], [29], [30]. This lowered capacity of hepatic xenobiotic clearance is often associated with abnormal drug reactions and further increased risk of liver disease and cancer in the elderly [31]. The UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2B15 (UGT2B15) gene was down-regulated (3.30 fold) in the liver of senior dogs fed PPB. This gene encodes glucuronosyltransferase that catalyzes glucuronidation in phase II reactions of xenobiotic metabolism and, therefore, its mutation increases abnormal drug metabolism and tumorigenesis [32]. Therefore, decreased expression of UGT2B15 in senior dogs may contribute to the decreased efficacy of hepatic xenobiotic metabolism with age. Glutathione-S-transferase pi 1 (GSTP1), which encodes glutathione-S-transferase (GST), was up-regulated in senior dogs fed APB (4.41 fold) or PPB (12.60 fold). The GST gene plays an important role in the clearance of cellular xenobiotics, carcinogens, [33] and defense against oxidative stress [34]. It is likely that increased expression of GSTP1 gene in the liver of aged dogs may reflect a physiological adaptation to an increase in xenobiotic loads and oxidative stress with age. To our knowledge, however, no experiments have reported an age-associated increase in hepatic GSTP1 expression, although it is reported that GSTP1 expression and GST activity in normal colonic mucosa increased with age in female adults [35]. Further research is required to explore age-related GSTP1 regulation on hepatic xenobiotic metabolism and oxidative stress.

There were numerous age-associated alterations in genes related to signaling transduction, such as RAS (RASGRP1), TGF-β (FST, THBS1), androgen receptor (NCOA2), and phosphatidylinositol (INPP1) pathways. Therefore, modification of intracellular signaling pathways may be an integral part of the aging process in the liver. The signaling pathways mentioned above are associated with inflammation and immune response in the liver. RASGRP1 is involved in the development and activation of several immune cell types [36], [37]. Up-regulated RASGRP1 expression (2.63 fold), as observed in senior dogs consuming PPB, may be related to increased inflammatory response as is frequently observed with aging [31]. Senior dogs fed APB (5.39 fold) or PPB (3.73 fold) had decreased expression of follistatin (FST) that has been related to various cellular processes such as cell development, wound healing, apoptosis, and immune response by antagonizing activin activity in the TGF-β signaling pathway [38]. It is suggested that the decreased ability of FST to neutralize activin activity may lead to an increased risk of hepatic pathogenesis such as chronic inflammation and fibrosis [39]. Likewise, the decreased expression (4.28 fold) of thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), as observed in senior dogs fed APB, may also indicate the predisposition of the liver to inflammation and fibrosis with age because THBS1, a mediator of TGF-β signaling pathway, has been implicated in attenuating inflammatory response and fibrosis by limiting angiogenesis in the heart [40]. However, the role of TGF-β signaling pathway in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis remains speculative.

Diet-associated alterations in gene expression

The liver is the central organ to metabolize dietary nutrients. It has been reported that hepatic gene expression profiles were affected by protein quality and quantity in rats [41]. Moreover, a greater concentration of lipids in the APB diet (22.6%) than in the PPB diet (11.2%) and different fatty acid composition between these 2 diets were expected to induce hepatic gene expression differentially. In this study, however, dietary treatment resulted in a relatively small number of gene expression changes (36 genes) with inconsistent patterns of gene expression (Figure 2). The reason for this observation may be that both diets in this experiment were formulated to contain adequate amounts of dietary protein and essential amino acids for senior or young adult dogs. Furthermore, the lack of effect of dietary treatment on hepatic lipid composition and concentrations in this experiment may also explain why there were the small changes in diet-associated gene expression. Likewise, our previous experiment reported that hematology and blood metabolites involved in liver metabolism were not significantly affected by dietary treatment [4].

The APB diet contained a greater amount of animal-derived lipids high in saturated fatty acids and cholesterols, which are predisposing factors for liver abnormalities in the elderly [42], [43]. Therefore, we hypothesized that APB diet would affect gene expression changes to a greater extent in senior dogs than in young adult dogs. However, of 36 genes differentially expressed by dietary treatment, gene expression changes were more pronounced in young dogs (33 genes) than in senior dogs (3 genes), again suggesting the presence of age*diet interactions. The reason for this observation is not clear, but it is likely due to differences in feeding strategy between young adult and senior dogs. A restricted feeding method was used to maintain body weight of senior dogs in this experiment, which may attenuate the effects of diet on gene expression involved in hepatic metabolism because food restriction has been shown to result in an overall reduction in metabolic rate [10], [44].

Up-regulation of PDLIM3 (3.08 fold) and ALDH1A1 (2.18 fold) genes and down-regulation of MFSD2A gene (2.53 fold) were observed in the liver of senior dogs consuming APB. It is reported that ALDH1A1 expression was positively associated with hepatocyte cytotoxicity in response to saturated fatty acid insults [45]. Therefore, the observation for increased expression of ALDH1A1 gene may indicate that feeding animal-derived ingredient high lipids and saturated fatty acids to senior dogs increases incidence of hepatocyte damage and death. Although MFSD2A gene is highly expressed in the liver [46], its role in liver metabolism has not been elucidated. A recent experiment reported that MFSD2A acts as a tumor suppressor in the lung by regulating expression of genes related to cell cycle and extracellular matrix [47].

Young dogs consuming the APB diet had a down-regulation of several genes associated with cellular metabolism of ATP (ATP5C1), branched chain amino acids (BCKDHB), carbohydrates (PDHX), lipids (ASAH1, HSD11B1), and xenobiotics (UGT2A1). Moreover, genes associated with signal transduction (YWHAE, MET, RAC1, PPP3CB, and HBP1) were also down-regulated in the liver of young dogs consuming APB. The reason for this observation is not clear; however, it may be related to differences in nutrient intake and subsequent nutrient digestion between dogs fed APB and PPB. Based on our calculation using nutrient intake and nutrient digestibility from our previous experiment [4], young dogs fed APB digested 38% greater amount of lipids (32.3 vs. 22.0 g/d for APB vs. PPB) and 37% lower amount of protein (30.4 vs. 44.1 g/d for APB vs. PPB) as compared to young dogs fed PPB. Therefore, the decreased expression (3.72 fold) of BCKDHB, which encodes branched chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase required for branched chain amino acid catabolism, may be a consequence of a lower absorption of branched chain amino acids in young dogs fed APB. Moreover, the decreased gene expression (4.69 fold) of HSD11B1 (11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1) in young dogs fed APB may also be related to high fat intake and absorption. The HSD11B1 is an enzyme that converts 11-dehydrocorticosterone to active corticosterone (cortisol) and is highly expressed in liver and adipose tissue [48]. It has been reported that mice fed a high fat diet had decreased activity of HSD11B1 in the liver and adipose tissue, suggesting that its down-regulation may be an adaptive mechanism in response to high fat intake [48], [49].

The observation for decreased expression of genes associated with antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and catalase (CAT) in the liver of young dogs fed APB, was surprising because high lipid and/or cholesterol intake, as observed in young dogs fed APB, is expected to increase hepatic oxidative stress concomitant with increased expression of genes related to antioxidant enzymes [50], [51], [52]. It has been reported that feeding diets containing high cholesterol and lipids to rabbits decreased SOD and CAT activities in the liver [53], [54]. Similar reduction in SOD activity was also observed in the kidney and vascular tissues of rats fed high lipid diets [55]. Taken together, it may be suggested that high lipid and/or cholesterol intake as occurs when consuming animal-derived ingredients, may decrease expression of genes related to antioxidant enzymes and subsequently increase oxidative stress in the liver.

Although statistical differences were detected in expression of several genes due to diet in young dogs, such changes may be of little pathological relevance to hepatic function because all young dogs remained healthy and had normal growth during the entire experiment. In addition, our previous observation for serum metabolites and hematology in young dogs fed APB vs. PPB indicates normal liver function in young adult dogs [4]. It is speculated, therefore, that the diet-associated modulation of hepatic gene expression observed in young dogs may be an adaptive mechanism in response to the distinct diet composition.

In conclusion, using canine microarray technology, we have identified global gene expression in the liver as affected by age and diet. Among transcriptional changes, more genes appeared to be altered by age as compared to diet, but age*diet interactions were also noted. Genes involved in cellular development, metabolism, and signaling transduction were differentially expressed by age and/or diet. In general, the gene expression changes in senior dogs suggest a propensity for liver disease and dysfunction because genes related to inflammation and oxidative stress were up-regulated, whereas genes related to regeneration and xenobiotic metabolism were down-regulated. Diet-induced gene expression changes were likely due to differences in feeding strategy between senior and young adult dogs, and in lipid concentrations between APB and PPB diet. In particular, genes encoding antioxidant enzymes were down-regulated in young adult dogs fed APB. This study, therefore, has highlighted hepatic alterations in global gene expression due to age and diet, providing a useful foundation for future research pertaining to age-dependent changes in hepatic physiology and pathogenesis, and nutritional intervention.

Materials and Methods

Animals, diets and experimental design

All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #02056) prior to initiation of the experiment. All animal care, handling, and sampling procedures are detailed in Swanson et al. [4]. In short, 6 senior (average age = 11.1 y at baseline; Kennelwood Inc., Champaign, IL) and 6 young (8 wk at baseline; Marshall Farms USA, Inc., North Rose, NY) female beagles were randomly allotted to 1 of 2 dietary treatments for 12 months. One diet was an animal protein-based diet (APB) containing 28.0% crude protein (CP), 22.6% fat, and 4.8% total dietary fiber (TDF). The other diet was a plant protein-based diet (PPB) containing 25.5% CP, 11.2% fat, and 15.2% TDF. The APB diet was formulated with brewer's rice, chicken by-product meal, and poultry fat, while the PPB diet consisted mainly of corn, soybean meal, and wheat middlings. Specific details of these 2 dietary treatments were reported previously [4]. Both diets were formulated to meet or exceed all nutrient requirements for canine growth and maintenance according to the Association of American Feed Control Officials [56].

Young dogs were fed ad libitum to allow for adequate growth, whereas senior dogs were fed a restricted amount of the diet to maintain baseline body weight throughout the experiment. Senior dogs maintained body weight and a fairly constant food intake over the course of the experiment, consuming similar amounts of food (APB: 199.1 vs. 183.5 g dry matter/d; PPB: 250.4 vs. 235.2 g dry matter/d), energy (APB: 1071 vs. 987 kcal/d; PPB: 1190 vs. 1117 kcal/d), protein (APB: 55.7 vs. 51.4 g/d; PPB: 63.9 vs. 60.0 g/d), fat (APB: 45.0 vs. 41.5 g/d; PPB: 28.0 vs. 26.3 g/d), and fiber (APB: 9.6 vs. 8.8 g/d; PPB: 38.1 vs. 35.8 g/d) during the early (3 months after baseline) and late (10 months after baseline) stages of the experiment. Young dogs also had similar food (APB: 150.4 vs. 148.6 g dry matter/d; PPB: 225.6 vs. 237.7 g dry matter/d), energy (APB: 809 vs. 800 kcal/d; PPB: 1071 vs. 1129 kcal/d), protein (APB: 42.1 vs. 41.6 g/d; PPB: 57.7 vs. 60.6 g/d), fat (APB: 34.0 vs. 33.6 g/d; PPB: 25.3 vs. 26.6 g/d), and fiber (APB: 7.2 vs. 7.1 g/d; PPB: 34.3 vs. 36.1 g/d) intakes at the 3 and 10-month time points. Although similar food and macronutrient intakes were observed over time in young dogs, it occurred with much different body weights (6.2 kg at 3 months vs. 9.0 kg at 10 months). Therefore, macronutrient intake per kg body weight was much greater at 3 months, a period of rapid growth, than at 10 months when growth is much slower.

Sample collection, RNA extraction, and microarray data analyses

After 12 months of experiment, dogs were fasted for 12 hours and euthanized using a lethal dose (130 mg/kg body weight) of sodium pentobarbital (Euthasol®, Virbac Corp., Fort Worth, TX). Liver tissue was immediately collected, flash frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Total cellular RNA was isolated from liver tissue using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA concentration was measured using a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and RNA integrity was verified on a 1.2% denaturing agarose gel.

The procedures for microarray data analyses were described previously by Swanson et al. [6]. In short, the prepared RNA samples were hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip® Canine Genome Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). After hybridization, chips were washed and stained with streptavidin-conjugated phycoerythrin dye (Invitrogen) enhanced with biotinylated goat anti-streptavidin antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) utilizing an Affymetrix GeneChip® Fluidics Station 450 and GeneChip® Operating Software. Images were then scanned using an Affymetrix GeneChip® Scanner 3000. Of the 23,836 probe sets on the array, 13,778 probe sets were expressed in the liver tissue and were used to determine effects of age and diet on gene expression profiles. Functional classification was made by the database SOURCE (http://source.stanford.edu) [57]. All microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) archives (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Liver lipid analyses

Lipid concentrations in the liver tissue were measured by gas chromatography [58]. In short, the liver tissue was homogenized using a Fisher Powergen Model 125 tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Internal standards and 0.1 g liver tissue were passed through hexane to extract the lipids. Fatty acid composition of the extracted lipids was measured using gas chromatography (Hewlett-Packard 5890A Series II) and external standards for identification and quantification.

Statistical analysis

Individual animal was the experimental unit for all analyses. Differential expression of the microarray data was evaluated using the limma package [59]. A linear model for the four age x diet groups was fit for each probe set. Differences between groups were then extracted from the model as contrasts. An empirical Bayes “shrinkage” method was employed on the standard errors to improve power for small sample sizes [59]. Lastly, multiple test correction of P-values was done using the false discovery rate (FDR) method [60]. Gene transcripts having >2.0-fold change and FDR <0.10 were considered significantly different. Data for hepatic lipid concentrations were analyzed using the Proc Mixed procedure of SAS (SAS Inst, Inc., Cary, NC). A probability of P<0.05 was accepted statistically significant and 0.05<P<0.10 was considered as a trend for hepatic lipid concentrations.

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Carole Wilson and Jenny Drnevich with microarray and statistical analyses is also greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: This research was supported by Pyxis Genomics, Inc., Chicago, IL. However, no other competing interests exist.

Funding: This research was supported by Pyxis Genomics, Inc., Chicago, IL, and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) and the University of Illinois, under the auspices of the NCSA/UIUC Faculty Fellows Program. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Schmucker DL. Age-related changes in liver structure and function: Implications for disease? Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swanson KS. Using genomic biology to study liver metabolism. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2008;92:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2007.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoskins JD. The Liver and Exocrine Pancreas. In: Hoskins JD, editor. Geriatrics and Gerontology of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2004. pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson KS, Kuzmuk KN, Schook LB, Fahey GC., Jr Diet affects nutrient digestibility, hematology, and serum chemistry of senior and weanling dogs. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1713–1724. doi: 10.2527/2004.8261713x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzmuk KN, Swanson KS, Tappenden KA, Schook LB, Fahey GC., Jr Diet and age affect intestinal morphology and large bowel fermentative end-product concentrations in senior and young adult dogs. J Nutr. 2005;135:1940–1945. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson KS, Vester BM, Apanavicius CJ, Kirby NA, Schook LB. Implications of age and diet on canine cerebral cortex transcription. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1314–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanson KS, Belsito KR, Vester BM, Schook LB. Adipose tissue gene expression profiles of healthy young adult and geriatric dogs. Arch Anim Nutr. 2009;63:160–171. doi: 10.1080/17450390902733934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middelbos IS, Vester BM, Karr-Lilienthal LK, Schook LB, Swanson KS. Age and diet affect gene expression profile in canine skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vester BM, Liu KJ, Keel TL, Graves TK, Swanson KS. In utero and postnatal exposure to a high-protein or high-carbohydrate diet leads to differences in adipose tissue mRNA expression and blood metabolites in kittens. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1136–1144. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509371652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CK, Klopp RG, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene expression profile of aging and its retardation by caloric restriction. Science. 1999;285:1390–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5432.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouchard D, Morisset D, Bourbonnais Y, Tremblay GM. Proteins with whey-acidic-protein motifs and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:167–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bingle L, Cross SS, High AS, Wallace WA, Rassl D, et al. WFDC2 (HE4): a potential role in the innate immunity of the oral cavity and respiratory tract and the development of adenocarcinomas of the lung. Respir Res. 2006;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumiyoshi M, Sakanaka M, Kimura Y. Chronic intake of a high-cholesterol diet resulted in hepatic steatosis, focal nodular hyperplasia and fibrosis in non-obese mice. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:378–385. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Aniello A, D'Onofrio G, Pischetola M, D'Aniello G, Vetere A, et al. Biological role of D-amino acid oxidase and D-aspartate oxidase. Effects of D-amino acids. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26941–26949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comai S, Costa CVL, Ragazzi E, Bertazzo A, Allegri G. The effect of age on the enzyme activities of tryptophan metabolism along the kynurenine pathway in rats. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2005;360:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okar DA, Manzano A, Navarro-Sabate A, Riera L, Bartrons R, et al. PFK-2/FBPase-2: maker and breaker of the essential biofactor fructose-2,6-bisphosphate. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:30–35. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01699-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atherton HJ, Gulston MK, Bailey NJ, Cheng KK, Zhang W, et al. Metabolomics of the interaction between PPAR-alpha and age in the PPAR-alpha-null mouse. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:259. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rayasam GV, Tulasi VK, Sodhi R, Davis JA, Ray A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: more than a namesake. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:885–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin JL, Wang GL, Shi XR, Darlington GJ, Timchenko NA. The age-associated decline of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta plays a critical role in the inhibition of liver regeneration. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3867–3880. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00456-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneeman BO, Richter D. Changes in plasma and hepatic lipids, small intestinal histology and pancreatic enzyme activity due to aging and dietary fiber in rats. J Nutr. 1993;123:1328–1337. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.7.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cree MG, Newcomer BR, Katsanos CS, Sheffield-Moore M, Chinkes D, et al. Intramuscular and liver triglycerides are increased in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3864–3871. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hijona E, Hijona L, Arenas JI, Bujanda L. Inflammatory mediators of hepatic steatosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2010. 837419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Bergen WG, Mersmann HJ. Comparative aspects of lipid metabolism: impact on contemporary research and use of animal models. J Nutr. 2005;135:2499–2502. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.11.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flowers MT, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase and its relation to high-carbohydrate diets and obesity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2009;1791:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costello LC, Franklin RB. ‘Why do tumour cells glycolyse?’: from glycolysis through citrate to lipogenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;280:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-8841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura MT, Nara TY. Structure, function, and dietary regulation of delta6, delta5, and delta9 desaturases. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:345–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.121803.063211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karten B, Peake KB, Vance JE. Mechanisms and consequences of impaired lipid trafficking in Niemann-Pick type C1-deficient mammalian cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2009;1791:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott SP, Yu M, Xu H, Haslam DB. Forssman synthetase expression results in diminished shiga toxin susceptibility: a role for glycolipids in determining host-microbe interactions. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6543–6552. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6543-6552.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeeh J, Platt D. The aging liver: structural and functional changes and their consequences for drug treatment in old age. Gerontology. 2002;48:121–127. doi: 10.1159/000052829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wauthier V, Verbeeck RK, Calderon PB. The effect of ageing on cytochrome p450 enzymes: consequences for drug biotransformation in the elderly. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:745–757. doi: 10.2174/092986707780090981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao SX, Dhahbi JM, Mote PL, Spindler SR. Genomic profiling of short- and long-term caloric restriction effects in the liver of aging mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10630–10635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191313598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maruo Y, Iwai M, Mori A, Sato H, Takeuchi Y. Polymorphism of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and drug metabolism. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6:91–99. doi: 10.2174/1389200053586064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aliya S, Reddanna P, Thyagaraju K. Does glutathione S-transferase Pi (GST-Pi) a marker protein for cancer? Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:319–327. doi: 10.1023/a:1026036521852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goto S, Kawakatsu M, Izumi S, Urata Y, Kageyama K, et al. Glutathione S-transferase pi localizes in mitochondria and protects against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1392–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoensch H, Peters WH, Roelofs HM, Kirch W. Expression of the glutathione enzyme system of human colon mucosa by localisation, gender and age. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1075–1083. doi: 10.1185/030079906X112480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SH, Yun S, Lee J, Kim MJ, Piao ZH, et al. RasGRP1 is required for human NK cell function. J Immunol. 2009;183:7931–7938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Priatel JJ, Chen X, Huang YH, Chow MT, Zenewicz LA, et al. RasGRP1 regulates antigen-induced developmental programming by naive CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:666–676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison CA, Gray PC, Vale WW, Robertson DM. Antagonists of activin signaling: mechanisms and potential biological applications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones KL, de Kretser DM, Patella S, Phillips DJ. Activin A and follistatin in systemic inflammation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;225:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chatila K, Ren G, Xia Y, Huebener P, Bujak M, et al. The role of the thrombospondins in healing myocardial infarcts. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2007;5:21–27. doi: 10.2174/187152507779315813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endo Y, Fu Z, Abe K, Arai S, Kato H. Dietary protein quantity and quality affect rat hepatic gene expression. J Nutr. 2002;132:3632–3637. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilar L, Oliveira CP, Faintuch J, Mello ES, Nogueira MA, et al. High-fat diet: a trigger of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis? Preliminary findings in obese subjects. Nutrition. 2008;24:1097–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wouters K, van Gorp PJ, Bieghs V, Gijbels MJ, Duimel H, et al. Dietary cholesterol, rather than liver steatosis, leads to hepatic inflammation in hyperlipidemic mouse models of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:474–486. doi: 10.1002/hep.22363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JV, Heilbronn LK, Ravussin E. Energy restriction and aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2004;7:615–622. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Z, Srivastava S, Yang X, Mittal S, Norton P, et al. A hierarchical approach employing metabolic and gene expression profiles to identify the pathways that confer cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells. BMC Syst Biol. 2007;1:21. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angers M, Uldry M, Kong D, Gimble JM, Jetten AM. Mfsd2a encodes a novel major facilitator superfamily domain-containing protein highly induced in brown adipose tissue during fasting and adaptive thermogenesis. Biochem J. 2008;416:347–355. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spinola M, Falvella FS, Colombo F, Sullivan JP, Shames DS, et al. MFSD2A is a novel lung tumor suppressor gene modulating cell cycle and matrix attachment. Mol Cancer. 9:62. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morton NM, Ramage L, Seckl JR. Down-regulation of adipose 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 by high-fat feeding in mice: a potential adaptive mechanism counteracting metabolic disease. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2707–2712. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drake AJ, Livingstone DE, Andrew R, Seckl JR, Morton NM, et al. Reduced adipose glucocorticoid reactivation and increased hepatic glucocorticoid clearance as an early adaptation to high-fat feeding in Wistar rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146:913–919. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Folmer V, Soares JC, Gabriel D, Rocha JB. A high fat diet inhibits delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase and increases lipid peroxidation in mice (Mus musculus). J Nutr. 2003;133:2165–2170. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuzawa-Nagata N, Takamura T, Ando H, Nakamura S, Kurita S, et al. Increased oxidative stress precedes the onset of high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity. Metabolism. 2008;57:1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H, Mu Z, Xu L, Xu G, Liu M, et al. Dietary lipid level induced antioxidant response in Manchurian trout, Brachymystax lenok (Pallas) larvae. Lipids. 2009;44:643–654. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Birkner E, Grucka-Mamczar E, Stawiarska-Pieta B, Birkner K, Zalejska-Fiolka J, et al. The influence of rich-in-cholesterol diet and fluoride ions contained in potable water upon the concentration of malondialdehyde and the activity of selected antioxidative enzymes in rabbit liver. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;129:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang WC, Yu YM, Wu CH, Tseng YH, Wu KY. Reduction of oxidative stress and atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic rabbits by Dioscorea rhizome. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:423–430. doi: 10.1139/y05-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts CK, Barnard RJ, Sindhu RK, Jurczak M, Ehdaie A, et al. Oxidative stress and dysregulation of NAD(P)H oxidase and antioxidant enzymes in diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2006;55:928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.AAFCO. Official Publication. Oxford, IN: Assoc Am Feed Control Offic, Inc; 2003. 476 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diehn M, Sherlock G, Binkley G, Jin H, Matese JC, et al. SOURCE: a unified genomic resource of functional annotations, ontologies, and gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:219–223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lepage G, Roy CC. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one-step reaction. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smyth GK. Linear Models and Empirical Bayes Methods for Assessing Differential Expression in Microarray Experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. Berkely (CA): Berkely Electronic Press; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc Ser. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]