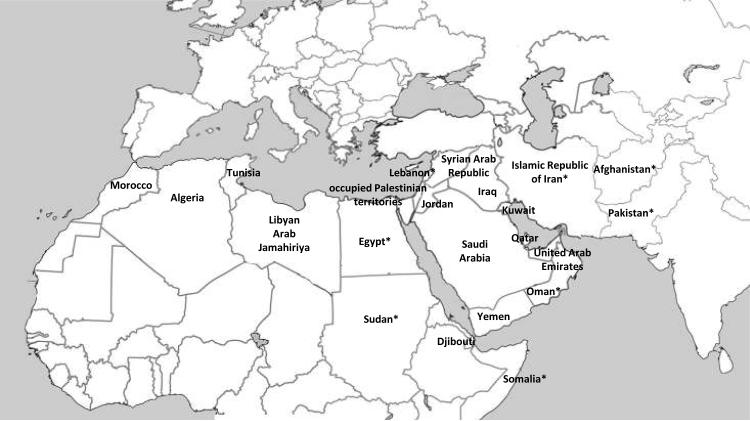

Of all areas of world, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA, see Figure 1 for countries included in this issue's classification) may engender the most perceptions and misperceptions about the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the face of a paucity of accessible data.

Figure 1. The Middle East and North Africa.

*Indicates country with original data included in this special issue. Countries included here do not necessarily correspond to those included other organizations' definition.

For example, the MENA region is perceived as the area of the world least affected by HIV/AIDS. According to most estimates, the overall prevalence of persons living with HIV/AIDS in the region is well below the world average [1]. On the other hand, there is also the perception that the infection rate is severely under-estimated among the marginalized populations most affected by HIV/AIDS, namely injection drug users (IDU), men who have sex with men (MSM), and female sex workers (FSW). The seldom-estimated size of these populations [2] and paucity of HIV prevalence and behavioral data from these groups may belie a greater existing burden of disease and the potential for rapidly evolving epidemics in some areas of the MENA.

Another perception is that the threat of HIV to the region comes primarily from outside. Indeed, case reporting, patterns of migration, and molecular epidemiology [3,4,5] corroborate multiple, diverse origins of HIV from exogenous sources throughout three decades of the epidemic. A self-fulfilling result is that HIV testing is often targeted disproportionately to immigrant populations in many countries of the region [6]. Yet, there is also emerging evidence of sustained endogenous HIV transmission among most-at-risk populations (MARPs) including IDU, MSM, and FSW [4]. An effective response for the MENA must therefore also be home grown and based on locally-appropriate research among these populations [7–12].

It is also widely perceived that political and socio-cultural sensitivities restrict access to HIV-related data and stifle relevant research in the MENA. While these factors may contribute to the apparent lack of data, limited experience and capacity in designing, conducting, and disseminating the findings of local HIV research are also severe barriers.

Fortunately, concerted efforts to address these barriers and move the field of HIV/AIDS research in the MENA from perception and misperception to a sound evidence base are being scaled-up. For example, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recognized the need for new HIV/AIDS research in the region and, since 2006, have supported meetings in Cairo, Tunis, Beirut, Rabat and elsewhere in order to improve understanding of the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the region, to stimulate productive research collaborations between US- and MENA- based investigators, and generate innovative research grant submissions. One conclusion from these meetings was the need to increase the visibility of recent research from the MENA through publications in high impact, peer-reviewed scientific journals. Also, WHO and UNAIDS have focused their investment in recent years in training of national experts on state-or-the art methodologies for community-based surveys among IDU, MSM, and male and female sex workers in addition to technical and financial support to such epidemiological studies.

This special issue of AIDS is an output of these concerted efforts to build research and scientific writing capacity and promote timely dissemination of recent HIV/AIDS research findings from the MENA. Several of the guest editors of this special issue first met at the Tunis conference and AUB subsequently organized a workshop in Beirut with funding from the Ford Foundation. At that meeting, researchers shared epidemiological and behavioral research findings, discussed common methodological and ethical challenges, and concurred on a complementary set of articles to prioritize for publication. A second workshop in Beirut funded by the World Health Organization (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) and the Ford Foundation (Regional Office for the Middle East and North Africa), comprised an intensive ten-day didactic and mentored retreat to generate ten manuscripts for simultaneous publication in this special issue funded by NIMH. The articles herein testify to the success of these workshops, the dedication of the authors, and the political support of their respective countries to make their data publicly available.

The first article [4] is based on the MENA HIV/AIDS Synthesis Project [13] and is the most comprehensive effort to gather and synthesize all available data on HIV/AIDS in the MENA to date, identifying and interpreting several thousand sources from the published and grey literature. Contrary to perception, there is a considerable quantity of epidemiological data on HIV/AIDS in the MENA although fragmented across different disciplines, organizations, and geographic levels. Large numbers of focused assessments, reviews, and studies have never been published, are not easily accessible, and are disseminated only within small circles as confidential or unofficial reports. An encouraging conclusion of the review is that the quality of data from the region has steadily improved in recent years. The second article also synthesizes existing information from across the region, focusing on HIV testing and counseling practices and policies and complemented with original fieldwork in Oman, Egypt, Sudan, and Pakistan [6]. The work describes the predominance of mandatory testing in many countries, particularly targeting migrant and foreign workers, and highlights the need for true voluntary testing with accessibility to the populations most at risk.

The majority of articles in this special issue present the first integrated biological and behavioral surveillance data for several countries, applying state of the art methods, such as respondent-driven sampling (RDS) to survey FSW, IDU, and MSM in Lebanon [7], IDU in Egypt [8], FSW in Sudan [10] and Somalia [11], and variations of venue-based or time-location sampling (TLS) to survey FSW in Afghanistan [12] and street children in Egypt [9]. These studies demonstrate the feasibility of reaching hidden populations even under the higher real or perceived stigma affecting MSM, FSW, and IDU in the MENA. The studies describe the unique challenges and locally-generated methodological solutions in implementing RDS and TLS in the region. One study from Pakistan presents the development and application of a pragmatic yet comprehensive method to estimate the size of hidden populations [2], an under-appreciated first step absolutely necessary in guiding the public health response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic worldwide. The final article includes updated data on antiretroviral drug resistance mutations in Iran, a testament to that country's regional scientific leadership [5].

A final misperception that merits carefully consideration is that the MENA is homogeneous in ways protective against HIV. The near universality of Islam with accompanying male circumcision and probably limited connectivity of sexual networks due to conservative cultural norms may slow HIV transmission [4,13]. Indeed, with the possible exception of parts of Sudan, sustainable HIV epidemics in the general population have generally not occurred in the region. However, the MENA is not homogeneous culturally or epidemiologically. A listing of the countries included in our definition of MENA makes this clear: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, and the occupied Palestinian territories (Figure 1). In the region's southern front (Sudan, Somalia, and Djibouti) generalized epidemics may have occurred in at least parts of these countries. The MENA's eastern flank includes the world's number one producer (Afghanistan) and per capita consumer (Iran) of opioids with accompanying serious HIV epidemics among IDU. Throughout the region, male-male sexual behavior and sex work exist largely under the radar, but in some areas increasingly open despite strong stigma and severe legal and social proscription.

In conclusion, the diversity of the populations at risk and the contexts in which they find themselves in the MENA require innovative, tailored responses guided by rigorous local research. We also conclude that there is no cause for complacency anywhere in the region. Our hope is that this special issue will give voice to a part of the world that has been relatively under-represented in the scientific literature in order to accelerate research and advocate for more vigorous and effective prevention and care programs. It is our perception that there is still a window of opportunity to prevent the further spread of HIV in each of the countries of the Middle East and North Africa.

Acknowledgements and Support

This special issue was made possible by the Faculty of Health Sciences of the American University of Beirut (AUB) through hosting regional workshops to build scientific writing capacity, donating faculty time and mentorship, and providing scientific guidance to bring the articles herein to fruition. The authors are also grateful to AUB for their gracious hospitality, the serenity afforded by the use of their campus, and their attentive logistical support. Funding for the production of this special issue was provided by the Ford Foundation (Cairo Regional Office), the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) of the World Health Organization (WHO), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Individual studies presented within this special issue were supported by the institutions and organizations indicated within each article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This work was written as part of Andrew D. Forsyth's official duties as a Government employee. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, NIH, HHS, or the United States Government.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . AIDS Epidemic Update: November 2009. UNAIDS/09.36E/JC1700E. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emmanuel F, Blanchard J, Zaheer HA, et al. The HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project mapping approach: an innovative approach for mapping and size estimation for groups at higher risk of HIV in Pakistan. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386737.25296.c4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mumtaz G, Hilmi N, Akala FA, et al. HIV-1 molecular epidemiology evidence and transmission patterns in the Middle East and North Africa. Sexually Transm Infect. 2010 doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.043711. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Raddad LJ, Hilma N, Mumtaz G, et al. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Middle East and North Africa. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386729.56683.33. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamkar R, Mohraz M, Lorestani S, et al. Assessing sub-type and drug-resistance associated mutations among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386738.32919.67. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermez J, Petrak J, Karkouri M, et al. A review of HIV testing and counseling policies and practices in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386730.56683.e5. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahfoud Z, Afifi R, Ramia S, et al. HIV/AIDS among female sex workers, injection drug users and men who have sex with men in Lebanon: Results of the first bio-behavioral surveys. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386733.02425.98. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soliman C, Rahman IA, Shawky S, et al. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of male injection drug users in Cairo, Egypt. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386731.94800.e6. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nada KH, Suliman EDA. Violence, abuse, alcohol and drug use, and sexual behaviors in street children of Greater Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386732.02425.d1. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelrahim MS. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of female sex workers in Khartoum, north Sudan. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386734.79553.9a. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kriitmaa K, Osman m, Bozecevic I, et al. HIV prevalence and characteristics of sex work among female sex workers in Hargeisa, Somaliland, Somalia. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386735.87177.2a. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd CS, Nasir A, Stanekzai MR, et al. HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C prevalence and associated risk behaviors among female sex workers in three Afghan cities. AIDS. 2010 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000386736.25296.8d. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I, et al. Time for Strategic Action. Middle East and North Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project. World Bank/UNAIDS/WHO Publication; 2010. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: Evidence on levels, distribution and trends. [Google Scholar]