Abstract

Rapamycin (Rap), a small molecule inhibitor of mTOR, is an immunosuppressant and several Rap analogs are cancer chemotherapeutics. Further pharmacological development will be significantly facilitated if in vivo reporter models are available to enable monitoring of molecular-specific pharmacodynamic actions of Rap and its analogs. Herein we present the use of a Gal4→Fluc reporter mouse for the study of Rap-induced mTOR/FKBP12 protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in vivo using a mouse two-hybrid (M2H) transactivation strategy, a derivative of the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system applied to live mice. Upon treatment with Rap, a bipartite transactivator was reconstituted and transcription of a genomic firefly luciferase (Fluc) reporter was activated in a concentration-dependent (Kd = 2.3 nM) and FK506-competitive (Ki = 17.1 nM) manner in cellulo as well as in a temporal and specific manner in vivo. In particular, following a single dose of Rap (4.5 mg/kg, i.p.), peak Rap-induced PPIs were observed in the liver at 24 h post treatment with photon flux signals 600-fold over baseline, which correlated temporally with suppression of p70S6K activity, a downstream effector of mTOR. The Gal4→Fluc reporter mouse provides an intact physiological system to interrogate PPIs and molecular-specific pharmacodynamics during drug discovery and lead characterization. Imaging protein interactions and functional proteomics in whole animals in vivo may serve as a basic tool for screening and mechanism-based analysis of small molecules targeting specific PPIs in human diseases.

Introduction

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a 289-kDa serine-threonine kinase important in regulation of cell growth and proliferation (1, 2). Functions of mTOR can be inhibited by the small molecule rapamycin (Rap) through formation of a ternary complex comprising Rap, FKBP12 (the 12-kDa immunophilin family member FK506- and Rap-binding protein), and mTOR via its FRB (FKBP-rapamycin binding) domain (3).

Rap is a FDA-approved immunosuppressant agent used to prevent organ rejection following transplantation (4). In addition, Rap and Rap analogs, alone or in combination with other drugs, are undergoing clinical trials for treatment of metastatic and advanced cancers, including brain, breast, and other solid tumors (5, 6). Recently, a Rap analog, temsirolimus, has been approved for use in treating advanced renal cell carcinoma (7). Mechanistically, Rap provides temporal and quantitative control of gene expression through its ability to associate with FKBP12 and FRB, which are critical in the mTOR signaling pathway through regulating protein translation and controlling autophagy (8, 9). Given that many questions regarding mTOR complex signaling remain unanswered, gaining insight into the pharmacological action of Rap and analogs at the molecular level in vivo may address many of these questions (10).

Pharmacodynamic analysis is key during early-phase clinical trials to determine the relationships between drug dose and target inhibition as well as to monitor downstream effects of target inhibition (11). Most conventional methods to monitor pharmacodynamics, including Western-blot analysis, immunohistochemical staining or flow cytometry determinations, require either labor-intensive sample preparation procedures or high-quality monoclonal antibodies and cannot readily provide information regarding drug impact over time or in intact organ systems (11–13). Integration of genome-wide analysis, proteomics and bioinformatics can assist the development of pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic evaluation by a systematic approach (14–16), but these techniques are at a relatively early stage of development.

Recent advances in molecular imaging combined with reporter animals can recapitulate genomic alterations in human diseases and are reshaping the process of new drug development at many levels (17). First, an effective readout reflecting real-time pharmacodynamic changes can be a powerful tool to monitor therapeutic effects in a spatially- and tissue-specific manner. Second, molecular imaging may reduce cost during drug development, since pharmacodynamic studies in animals can inform clinical trials and accelerate the translation process (18, 19). Third, non-invasive imaging allows chronological monitoring for delayed activities and toxicity of drugs in living animals. However, one of the major challenges in in vivo pharmacodynamic monitoring is the lack of high fidelity reporter models to visualize pharmacodynamics of therapeutic agents in a mechanistically appropriate manner. In this regard, using a universal Gal4→Fluc reporter mouse (20), the inducible association of FRB and FKBP12 upon introduction of Rap enabled conditional activation of a luciferase reporter gene (Fig 1) (21–25). This platform could lead to broader applications of reporter models to study pharmacodynamics in the context of whole animals.

Figure 1. Conditional genomic reporter activation using a modified two-hybrid system.

(A) A crystallographic model of FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP(X3) domains in the absence of Rap. (B) Rap-induced association of FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP(X3) activate the reporter gene, Fluc. (FRB-VP16: green-magenta, G4BD-FKBP(X3): blue-orange, Rap: black, DNA: gray. Image adapted from RCSB PDB (www.pdb.org).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

Plasmids pBJ5-Frb-VP16-HA and pBJ5-Gal4-FKBP(X3), which express FRB-VP16-HA and G4BD-FKBP(X3) chimera proteins from a modified SV40 (SRα) promoter, were graciously provided by Dr. T. Wandless and Dr. G. Crabtree (26). pRluc-N3 was purchased from BioSignal Packard (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). D-Luciferin was obtained from Biosynth (Naperville, IL, USA) and both rapamycin and FK506 were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Native coelenterazine was from Biotium (Haywood, CA, USA).

Cell cultures and transfection

HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells, HeLa cells which stably express firefly luciferase under the control of a concatenated Gal4 promoter (5x Gal4), were described previously (20). HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells were maintained in DMEM media containing 10% heat-inactive fetal bovine serum and 1% glutamine. Transfections were performed with FuGENE-6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Construction of Frb mutant plasmid, mtFrb (S2035I)

Mutant Frb (S2035I), hereafter referred to as mtFrb, was prepared by the Quikchange mutagenesis method (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, PCR was performed with the parent plasmid pBJ5-Frb-VP16-HA and overlapping oligonucleotides containing relevant base changes (sense primer: 5‘-gcatgaaggcctggaagaggcaattcgtttgtactttgg-3’; antisense primer: 5'-ccaaagtacaaacgaattgcctcttccaggccttcatgc-3'). The product was re-ligated to the parent vector, and then transformed into TOP10 competent E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The expected mutation was confirmed by sequencing.

Bioluminescence imaging of cells

HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells (2.5 × 105 cells per well for 24-well plates; 1 × 105 cells per well for 96-well plates) were transiently cotransfected with pairs of plasmids (200 ng DNA each for 24-well plates; 30 ng each for 96-well plates) using FuGENE-6 according to the manufacturer’s directions. For bioluminescence imaging, approximately 48 h after transfection, growth media was replaced with optically clear DMEM media containing appropriate drugs or vehicle and D-luciferin (D-luc, 150 µg / ml) (27). Cells were incubated for another 6 h and photon flux for each well was then measured with a charge-coupled device camera (IVIS 100; Caliper, Hopkinton, MA, USA) using the following parameters: exposure, 3 min; f-stop, 1; binning, 8; field of view, 15 cm; filter, open. Experiments were performed in triplicate. After IVIS imaging, an MTS assay for viable cell mass was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). MTS reagent (20 µL) was added to each well of a 96 well plate at a final volume of 200 µL per well. Samples were incubated for approximately 1 h. Absorbance of samples was measured against a background control (blank) at 490 nm. Data normalized by cell mass were expressed as mean photon flux ± SEM of triplicate wells (representative of three independent experiments).

Rap concentration-response curve and FK506 competitive inhibition assay

To determine the apparent Kd of Rap-induced FRB and FKBP12 association as well as the apparent Ki of FK506-mediated inhibition of protein association in live cells, HeLa/Gal4→Fluc reporter cells transfected with pBJ5-Frb-VP16-HA and pBJ5-Gal4-FKBP(X3) plasmid pairs were pretreated with Rap alone for 6 h prior to bioluminescence imaging with the indicated concentrations (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 1000 nM) or with Rap at the EC50 (1 nM) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of FK506 (1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 1000 nM).

Animal studies

Hydrodynamic injections (HDIs)

Animal care and protocols were approved by the Washington University Medical School Animal Studies Committee. Generation of the Gal4→Fluc transgenic reporter mouse strain was described (20). In vivo hepatocyte transfection of Gal4→Fluc reporter mice was performed using the hydrodynamic somatic gene transfer method as described previously (20). Briefly, plasmid pairs of pBJ5-Frb-VP16-HA and pBJ5-Gal4-FKBP(X3) or pBJ5-mtFrb-VP16-HA and pBJ5-Gal4-FKBP(X3) (15 µg per plasmid) together with pRluc-N3 (1 µg per mouse) were co-injected as indicated. Plasmids were diluted into PBS (pH 7.4) (1 ml/10 gm of body weight) and rapidly injected into tail veins of mice.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging

Bioluminescence imaging was performed in the IVIS 100 under 2.5% isoflurane anesthesia as described previously (20). First, background signals were recorded by imaging before HDIs (D-luc, 150 µg/g body weight, i.p.). Rluc activity was acquired 20 h after HDIs by injection of coelenterazine (1 mg/kg body weight, i.v.) to serve as a transfection control. 4 h later (generally no residual signal), D-luc (150 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) was administered followed by image acquisition 10 min post-injection providing the pre-treatment (0 h) activity. Immediate after pre-treatment IVIS imaging, groups of mice were treated with Rap (4.5 mg/kg in DMSO, i.p.) (n=6 for FRB-VP16 pair; n=2 for mtFRB-VP16 pair) or vehicle only (DMSO) (n=2). At the indicated times after treatment with Rap (6 h, 15 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h), mice were again injected with D-luc (i.p.) and imaged 10 min later (IVIS 100). Because of the highly inducible nature of the photon output, images 24 h after Rap treatment were obtained with different exposure times (1–10 sec) compared with later time points of the experiment (exposure time, 5 min) to avoid saturation of the CCD camera. Photon flux (photons/second) was quantified on images by contour-based regions of interests (ROIs) where the edge of the ROI was defined as 40% of peak values and analyzed with LivingImage 2.6 (Caliper) and IGOR (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) image analysis software. Data represent the mean ± SEM or range in each group imaged over the course of the experiment and are expressed relative to the pretreatment bioluminescence of the same mouse (photon flux, fold-initial).

Western blotting

HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells (3 × 106 per 10-cm dish) were transfected with the indicated pairs of plasmids (3 µg DNA each) followed by bioluminescence imaging 48 h after transfection. After a PBS wash, whole-cell lysates were prepared in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.5), 1% SDS and freshly combined with sodium orthovanadate (1 mM) and protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, P8340, Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Proteins (50 µg) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with primary antibodies (Abs) for VP16 (1:100, ab4808, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and G4BD (1:500, sc-510, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Immunoblots of G4BD were stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibody (1:2000, A2066, Sigma-Aldrich). Bound primary antibodies were visualized with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000) using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia, GE healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

A cohort of mice was subjected to HDIs and bioluminescence imaging prior to and at the indicated times after treatment with Rap or vehicle (6 h, 24 h, and 72 h) as above. Immediately after imaging, livers were harvested and approximately 3 gm of tissue were placed into 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% P-40) freshly combined with sodium orthovanadate (1 mM), protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (1:100, P0044, Sigma-Aldrich) and PMSF (2 mM), and homogenized at 4°C using a homogenizer (PT3000, Brinkmann). Samples were then centrifuged twice for 10 min at 14,000g to remove cell debris. Protein concentration measurement and Western blotting were performed as described above. Proteins (500 µg) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with primary Abs for phosphorylated p70S6K (S371) (1:1000, 9208, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and actin. Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with anti-p70S6K Ab (1:1000, 2708, Cell Signaling Technology).

Statistics

Curve fitting, EC50, Kd, and Ki values were determined with Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are presented as mean ± SEM or range.

RESULTS

In vitro studies

Concentration-response of Rap-induced PPIs and competitive inhibition by FK506

In HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells co-expressing the FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP chimera protein pairs, Rap increased bioluminescence signals in a concentration-dependent manner up to 3 nM. Maximum induction was 628-fold over baseline 6 h after addition of 3 nM of drug (Fig 2). Curve fitting of the data revealed an EC50 of 1.2 ± 0.02 nM with an apparent Kd of 2.3 ± 1.1 nM (n = 3). Under these conditions, reporter signals declined at concentrations higher than 3 nM (Supplementary Fig 1). Addition of FK506, a competitive inhibitor of Rap binding to FKBP, inhibited Rap-induced luciferase activity in the presence of 1 nM of Rap with a Ki of 17.1 nM, derived using the Cheng-Prusoff equation (28) (n =3) (Fig 3).

Figure 2. Concentration-dependent Rap-induced FRB/FKBP interactions.

HeLa/Gal4→Fluc reporter cells were co-transfected with plasmid pairs expressing FRB-VP16 and G4BP-FKBP, then treated with various concentrations of Rap for 6 h. Bioluminescence signals increased in a concentration-dependent manner up to 3 nM (Kd = 2.3 ± 1.1 nM). Data are shown as mean photon flux ± SEM (when larger than symbol) of triplicate wells.

Figure 3. Competitive inhibition by FK506.

HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells co-expressing FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP were treated with Rap at the EC50 (1 nM) as well as the indicated concentrations of FK506 for 6 h. The Ki of FK506-mediated inhibition of Rap-induced protein association was determined with the Cheng-Prusoff equation (Ki = 17.1 nM). Data are shown as mean photon flux normalized to cell mass ± SEM (when larger than symbol) of triplicate wells.

Abrogation of FRB and FKBP12 association by mutant FRB (S2035I)

HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells transiently transfected with plasmids expressing FRB-VP16 together with G4BD-FKBP and treated with 1 nM Rap produced 100-fold greater bioluminescence signals than vehicle-treated cells (Fig 4A). By comparison, the coexpression of mtFRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP produced no significant change in bioluminescence activity after treatment with 1 nM Rap (p ≫ 0.05). Western blots of whole cell lysates demonstrated similar expression levels of both FRB-VP16 and mtFRB-VP16 proteins as well as G4BD-FKBP proteins under each condition (Fig 4B). While quantitative analysis showed a 35% decrease in protein levels for mtFRB compared to wild type, the complete disruption of the Rap-induced bioluminescence signal with mtFRB-VP16 was most consistent with abrogation of Rap binding by mutation of ser2035 within FRB (29), rather than loss of protein.

Figure 4. Disruption of Rap-induced protein associations by mutant FRB (mtFRB) in cellulo.

Compared to untreated cells, HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells transiently expressing FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP produced 100-fold greater bioluminescence signals after treatment with 1 nM Rap for 6 h (A, upper panel). In contrast, cells transfected with the plasmid pair expressing mtFRB produced no significant signal change after Rap treatment (p ≫ 0.05) (A, lower panel). Western blot analysis (B) demonstrated comparable expression of FRB-VP16, mtFRB-VP16, as well as G4BP-FKBP from co-transfected HeLa/Gal4→Fluc cells treated with Rap (1 nM) for 6 h.

In vivo studies

Rap-Induced bioluminescence in Gal4→Fluc transgenic reporter mice

To demonstrate that Rap-induced transactivation of the reporter gene could be imaged in living animals, we performed somatic gene transfer by administering plasmid pairs expressing wild type FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP or mtFRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP along with Rluc by hydrodynamic injection (HDI) into Gal4→Fluc reporter mice. We obtained images of mice before hydrodynamic injection, before Rap or vehicle treatment (0 h) and at the indicated times after treatment (6 to 72 h). Photon flux from Rluc expression in the liver, obtained 4 h prior to Rap exposure (−4 h), showed comparable transfection efficiency of HDI between all three groups (Fig 5A, left column). After Rap treatment, photon flux arising from Fluc expression in the livers of mice receiving FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP reached maximal levels at 24 h and persisted for 3 days, whereupon the signal declined back to almost pretreatment levels (Fig 5A, top row). Signal 24 h after Rap treatment was almost 600-fold higher than the pre-treatment baseline (Fig 5B), achieving photon flux values of 4.6 × 108 ± 1.07 × 108 photons/sec.

Figure 5. Pharmacodynamic analysis of Rap by bioluminescence imaging in vivo.

Somatic gene transfer was performed by HDI of plasmid pairs expressing FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP or mtFRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP (along with Rluc as a transfection control) into Gal4→Fluc transgenic reporter mice. Mice were imaged before and after treatment with Rap (4.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle at the indicated times. (A) Transfection efficiency was similar between each group as indicated by Rluc signals (left column, representative images). Transgenic reporter mice receiving wild type plasmid pairs (top row, representative of n=6) produced peak Fluc signals 24 h after Rap treatment (4.6 × 108 ± 1.1 × 108 photons/sec) and returned to baseline within 72 h. Mice treated with vehicle showed no Fluc response (middle row, representative of n=2); mice receiving the mutant plasmid pair and treated with Rap also showed no Fluc response (bottom row, representative of n=2). (B) Rap-induced normalized photon flux (Fluc, fold-initial) as a function of time. Wild type FRB-VP16/G4BD-FKBP-induced signal increased 600-fold over the pre-treatment baseline at 24 h post Rap treatment. Data are presented as means ± SEM or range (when larger than symbol; diamond: FRB-VP16 and G4BP-FKBP with Rap; triangle: FRB-VP16 and G4BP-FKBP with vehicle; circle: mtFRB-VP16 and G4BP-FKBP with Rap).

As a control, mice were injected with the FRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP pair, treated with vehicle, and imaged over the same time course as described above. Vehicle had no effect on transactivation of the reporter gene (Fig 5A, middle row). Furthermore, mice expressing the mtFRB-VP16 and G4BD-FKBP pair showed no detectable signal induction in response to Rap treatment over the entire time course of the experiment (Fig 5A, bottom row; Fig 5B).

Attenuation of mTOR signaling after Rap treatment in transgenic reporter mice

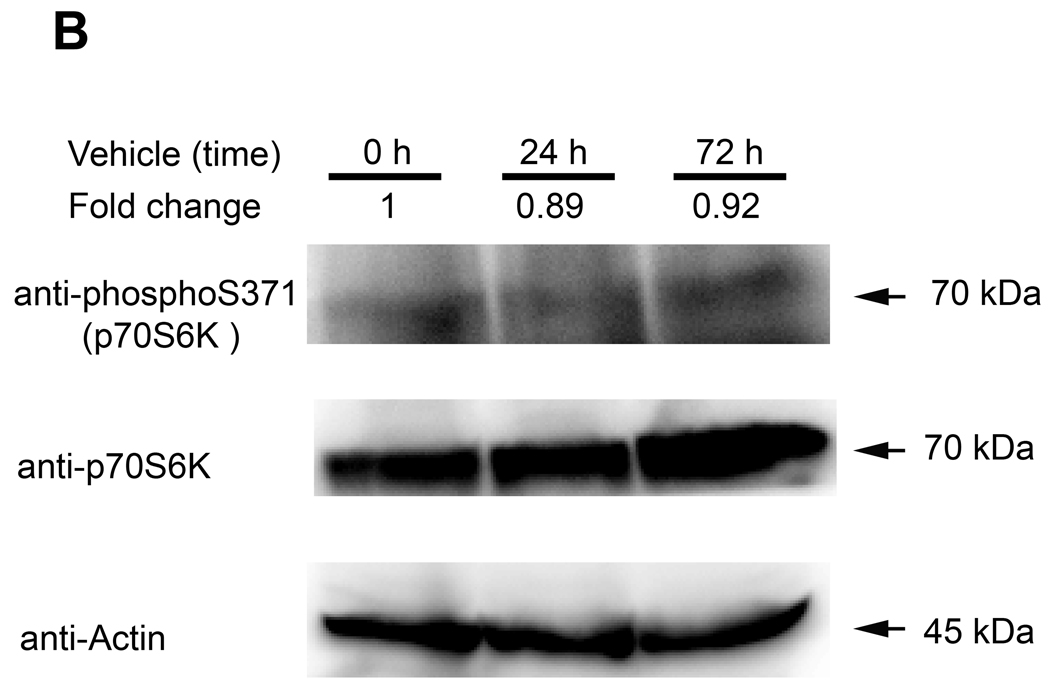

To independently validate functional mTOR activity in reporter mice in response to Rap treatment, we monitored phosphorylated p70S6K (S371), a downstream effector of mTOR, by Western analysis in another cohort of reporter mice subjected to HDI and bioluminescence imaging. Immediately after imaging, liver samples were harvested at the indicated times post Rap or vehicle treatment. Bioluminescence imaging results were similar to those shown in Fig 5 (data not shown). When normalized to total p70S6K and baseline levels before Rap treatment, phosphorylated p70S6K (S371) was attenuated at 6 h (0.33) and at 24 h (0.21) post Rap exposure and returned toward baseline at 72 h (0.63) (Fig 6A, top row). Total p70S6K remained unperturbed (Fig 6A, middle row). By contrast, there was no substantial difference in phosphorylated p70S6K (S371) in response to vehicle treatment (Fig 6B).

Figure 6. Suppression of p70S6K phosphorylation by Rap treatment in reporter mice.

Somatic gene transfer by HDI and subsequent bioluminescence imaging of Gal4→Fluc transgenic reporter mice were followed by harvest of liver samples before and at the indicated times post Rap or vehicle exposure. (A) Western blot analysis demonstrated attenuation of phosphorylated p70S6K (S371) at 6 h and 24 h post Rap treatment and recovery toward baseline at 72 h. The fold-change of phosphorylated p70S6K (S371) was normalized to the corresponding total p70S6K protein. (B) Phosphorylated p70S6K (S371) was relatively unaffected by vehicle treatment.

DISCUSSION

Rapamycin, or Sirolimus, is approved as an anti-rejection agent post organ transplantation and confers immunosuppressant properties through suppression of IL-2-induced T-cell proliferation and activation (30). Rapamycin-coated stents are also FDA-approved to reduce restenosis after coronary artery intervention through inhibition of vascular smooth cells (31, 32). Because of the versatile therapeutic potential of rapamycin associated with the mTOR signaling pathway as well as immunophilin function, various rapamycin analogs with modified and improved pharmacokinetic properties have been developed as effective therapeutics for organ transplantation, cancer, restenosis and neurodegenerative disorders (10). Temsirolimus and Everolimus are FDA-approved rapamycin analogs for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma through disruption of mTOR signaling and subsequent suppression of protein translation, cell cycle progression and angiogenesis (7, 33, 34). Recently, numerous non-immunosuppressive rapamycin analogs have been developed as novel candidate therapeutics for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases or stroke after the discovery of potent rapamycin-mediated neuroprotective properties for this class of compounds (35, 36). In addition to mTOR or immunophilin-related signaling pathways, rapamycin analogs also provide unique opportunities to regulate protein function through conditional control of protein stability, localization and protein-interactions in vivo (37).

In terms of pharmacodynamic monitoring of rapamycin or its analogs, current strategies employ biomarkers derived from either blood, skin or tumor samples of patients (38, 39). Real time RT-PCR, Western blot or immunohistochemical analysis for biomarkers, such as cytokines (IL-2, IL-4 or IL-10), or downstream targets of mTOR, such as eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein1 (4E-BP1) or p70S6 kinase (p70S6K) have been reported (5, 40, 41). However, a sensitive approach to quantitatively interrogate pharmacodynamics of Rap or its analogs in mouse models over time is lacking.

In vivo imaging, compared to conventional methods to monitor pharmacodynamics, permits the evaluation of drug effects on the target with quantitative, spatio-temporal resolution after various dosages and at any given time of interest (17, 18). Such a strategy will efficiently verify effects of drugs of interest in living organisms, such as reporter animals, without the requirement for high-quality antibodies and laborious sample processing. Most importantly, it enables non-invasive and longitudinal observation of target engagement and may help minimize the costs and time of pharmaceutical development.

The results of the present study demonstrate application of bioluminescence imaging to monitor pharmacodynamics of Rap in a continuous and non-invasive manner using transgenic mice that incorporate a genetically-encoded two-hybrid reporter strategy. In effect, the system allows a molecular-specific pharmacodynamic readout of Rap in living mice. The data reported herein show that Rap induced PPIs in a concentration-dependent and FK506-competitive manner. The Kd value derived from the transcriptional readout (2.3 ± 1.1 nM) compared favorably with previously reported values determined by luciferase and colorimetric complementation systems in cellulo (42, 43). Accordingly, in our system, FK506, a competitive inhibitor of Rap, diminished Rap-induced bioluminescence signals with a Ki of 17.1 nM, which is also comparable to the Ki of FK506 in other reported in vitro systems (42, 44). Note that our in vivo reporter system demonstrated a high level of signal induction (600-fold) 24 hours after treatment with Rap. By contrast, expression of mutant FRB (mtFRB S2035I), which abrogates binding to Rap, did not activate the reporter system in cellulo or in vivo. The slightly decreased mtFRB protein expression level observed in cells, compared to the wtFRB, could have resulted from the destabilized quality of mtFRB when not bound to Rap (3).

One arm of mTOR signaling controls translation via activation of p70S6K and inhibition of 4E-BP1 (41, 45, 46). Therefore, we used antibodies specific for S371 phosphorylation of p70S6K, a Rap-sensitive phosphorylation site critical for kinase activity, as an independent readout of mTOR activity (47, 48). As anticipated, suppression of p70S6K phosphorylation induced by Rap treatment correlated temporally with induction of bioluminescence signals, peaking at 24 h post Rap exposure in vivo, further validating the reporter strategy.

Note that reporter signals in cellulo produced by Rap-induced protein association plateaued in the presence of ~ 3 nM Rap and began to fall as the concentration increased (Supplementary Fig 1). This may have been due to the mechanism of action of Rap, which resulted in inhibition of mTOR signaling, thereby enhancing autophagy, repressing ribosomal protein synthesis and inhibiting translation over the time frame of these experiments (8, 9, 49). The transcriptional readout strategy may be sensitive to this Rap-induced activity over time, and therefore fail to fully engage reporter machinery after exposure to high concentrations of Rap for 6 hrs and longer. This stands in contrast to luciferase protein fragment complementation strategies wherein readouts occurred within minutes, were not dependent on new protein synthesis, and suppression of signals at high concentrations of Rap were not observed (42).

In vivo imaging is a field of ongoing and active research, wherein genetically encoded reporters in conjunction with optical imaging, including bioluminescence and fluorescence imaging, can add significant value to the drug development process due to efficiency, low cost and sensitivity (17, 18). An effective reporter animal model can serve as a useful tool to monitor effects of candidate drugs and bridge the preclinical studies to successful clinical translation. In the current study, our highly-inducible Gal4→Fluc transgenic reporter mice proved to be amenable to verifying pharmacodynamic effects of Rap on the basis of an in vivo M2H system. Our M2H transgenic model appears to have inherent high sensitivity while engaging the platform in an appropriate mammalian context. By contrast, conventional Y2H assays are often criticized for generating high rates of false-positive outputs (50), perhaps related to the study of PPIs of human gene products within the context of yeast, which do not necessary reproduce the relevant microenvironment, physiological context and subcellular localization required for high fidelity results (51). The M2H allows future high throughput assays based on monitoring changes in PPIs in response to novel pharmaceutical reagents in an environment better recapitulating human physiology. Furthermore, reporter systems with transcriptional amplification can enhance reporter gene expression from relatively weak promoters, such as the Gal4 promoter in our system (52, 53). Compared with other existing modalities to address PPIs, such as bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) systems and split reporter protein complementation, this signal-amplification character secondary to transcriptional cascades will be valuable in systems where signal output is low. On the other hand, a major caveat is the sacrifice in temporal resolution with transcriptional reporter strategies, both in terms of on-rates as well as off-rates, compared to post-translational strategies (54).

In conclusion, we demonstrated the feasibility of a M2H platform using a highly inducible Gal4→Fluc reporter mouse to monitor conditional PPIs at the level of transcriptional readouts using bioluminescence imaging. This reporter model may better reflect physiological conditions where PPIs are under intricate layers of control as well as provide a more sensitive assessment inherent to the broad dynamic range of this approach (20). This strategy may facilitate imaging studies of protein interactions, signaling cascades and drug development within the physiological context of living animals.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P50 CA94056 and a Fellowship from the Cancer Biology Pathway training program through the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital–Washington University School of Medicine (M.H.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham RT, Eng CH. Mammalian target of rapamycin as a therapeutic target in oncology. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:209–222. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science. 1996;273:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards SR, Wandless TJ. The rapamycin-binding domain of the protein kinase mammalian target of rapamycin is a destabilizing domain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13395–13401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700498200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groth CG, Backman L, Morales JM, Calne R, Kreis H, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin)-based therapy in human renal transplantation: similar efficacy and different toxicity compared with cyclosporine. Sirolimus European Renal Transplant Study Group. Transplantation. 1999;67:1036–1042. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199904150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sessa C, Tosi D, Vigano L, Albanell J, Hess D, et al. Phase Ib study of weekly mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor ridaforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669) with weekly paclitaxel. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1315–1322. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galanis E, Buckner JC, Maurer MJ, Kreisberg JI, Ballman K, et al. Phase II trial of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5294–5304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.23.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamada Y, Funakoshi T, Shintani T, Nagano K, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1507–1513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaragoza D, Ghavidel A, Heitman J, Schultz MC. Rapamycin induces the G0 program of transcriptional repression in yeast by interfering with the TOR signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4463–4470. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graziani EI. Recent advances in the chemistry, biosynthesis and pharmacology of rapamycin analogs. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:602–609. doi: 10.1039/b804602f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedley DW, Chow S, Goolsby C, Shankey TV. Pharmacodynamic monitoring of molecular-targeted agents in the peripheral blood of leukemia patients using flow cytometry. Toxicol Pathol. 2008;36:133–139. doi: 10.1177/0192623307310952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebes L, Potmesil M, Kim T, Pease D, Buckley M, et al. Pharmacodynamics of topoisomerase I inhibition: Western blot determination of topoisomerase I and cleavable complex in patients with upper gastrointestinal malignancies treated with topotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:545–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baselga J, Albanell J, Ruiz A, Lluch A, Gascon P, et al. Phase II and tumor pharmacodynamic study of gefitinib in patients with advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5323–5333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarker D, Workman P. Pharmacodynamic biomarkers for molecular cancer therapeutics. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;96:213–268. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)96008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chautard E, Thierry-Mieg N, Ricard-Blum S. Interaction networks: from protein functions to drug discovery. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2009;57:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.10.004. A review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrer-Alcon M, Arteta D, Guerrero MJ, Fernandez-Orth D, Simon L, Martinez A. The use of gene array technology and proteomics in the search of new targets of diseases for therapeutics. Toxicol Lett. 2009;186:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Molecular imaging strategies for drug discovery and development. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stell A, Belcredito S, Ramachandran B, Biserni A, Rando G, et al. Multimodality imaging: novel pharmacological applications of reporter systems. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;51:127–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Code of Federal Regulations. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pichler A, Prior JL, Luker GD, Piwnica-Worms D. Generation of a highly inducible Gal4-->Fluc universal reporter mouse for in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15932–15937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801075105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odagaki Y, Clardy J. Structural Basis for Peptidomimicry by the Effector Element of Rapamycin. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:10253. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonker HR, Wechselberger RW, Boelens R, Folkers GE, Kaptein R. Structural properties of the promiscuous VP16 activation domain. Biochemistry. 2005;44:827–839. doi: 10.1021/bi0482912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson KP, Yamashita MM, Sintchak MD, Rotstein SH, Murcko MA, et al. Comparative X-ray structures of the major binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506 (tacrolimus) in unliganded form and in complex with FK506 and rapamycin. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1995;51:511–521. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994014514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong M, Fitzgerald MX, Harper S, Luo C, Speicher DW, Marmorstein R. Structural basis for dimerization in DNA recognition by Gal4. Structure. 2008;16:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bayle JH, Grimley JS, Stankunas K, Gestwicki JE, Wandless TJ, Crabtree GR. Rapamycin analogs with differential binding specificity permit orthogonal control of protein activity. Chem Biol. 2006;13:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Real-time imaging of ligand-induced IKK activation in intact cells and in living mice. Nat Methods. 2005;2:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng Y, Prusoff W. Relationship between inhibition constant (ki) and the concentration of the inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Zheng XF, Brown EJ, Schreiber SL. Identification of an 11-kDa FKBP12-rapamycin-binding domain within the 289-kDa FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein and characterization of a critical serine residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4947–4951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai JH, Tan TH. CD28 signaling causes a sustained down-regulation of I kappa B alpha which can be prevented by the immunosuppressant rapamycin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30077–30080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serruys PW, Kutryk MJ, Ong AT. Coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:483–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra051091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poon M, Marx SO, Gallo R, Badimon JJ, Taubman MB, Marks AR. Rapamycin inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2277–2283. doi: 10.1172/JCI119038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atkins MB, Yasothan U, Kirkpatrick P. Everolimus. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:535–536. doi: 10.1038/nrd2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons WE, George EB, Dawson TM, Steiner JP, Snyder SH. Immunosuppressant FK506 promotes neurite outgrowth in cultures of PC12 cells and sensory ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3191–3195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruan B, Pong K, Jow F, Bowlby M, Crozier RA, et al. Binding of rapamycin analogs to calcium channels and FKBP52 contributes to their neuroprotective activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:33–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710424105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banaszynski LA, Sellmyer MA, Contag CH, Wandless TJ, Thorne SH. Chemical control of protein stability and function in living mice. Nat Med. 2008;14:1123–1127. doi: 10.1038/nm.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jimeno A, Rudek MA, Kulesza P, Ma WW, Wheelhouse J, et al. Pharmacodynamic-guided modified continuous reassessment method-based, dose-finding study of rapamycin in adult patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4172–4179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson BE, Jackman D, Janne PA. Rationale for a phase I trial of erlotinib and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) for patients with relapsed non small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:s4628–s4631. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller-Steinhardt M, Wortmeier K, Fricke L, Ebel B, Hartel C. The pharmacodynamic effect of sirolimus: individual variation of cytokine mRNA expression profiles in human whole blood samples. Immunobiology. 2009;214:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka C, O'Reilly T, Kovarik JM, Shand N, Hazell K, et al. Identifying optimal biologic doses of everolimus (RAD001) in patients with cancer based on the modeling of preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1596–1602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luker KE, Smith MC, Luker GD, Gammon ST, Piwnica-Worms H, Piwnica-Worms D. Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12288–12293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galarneau A, Primeau M, Trudeau L-E, Michnick S. b-Lactamase protein fragment complementation assays as in vivo and in vitro sensors of protein-protein interactions. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:619–622. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Remy I, Michnick S. Clonal selection and in vivo quantitation of protein interactions with protein-fragment complementation assays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5394–5399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shama S, Meyuhas O. The translational cis-regulatory element of mammalian ribosomal protein mRNAs is recognized by the plant translational apparatus. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:383–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Weng QP, Kozlowski MT, Belham C, Avruch J. Amino acid sufficiency and mTOR regulate p70 S6 kinase and eIF-4E BP1 through a common effector mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14484–14494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moser BA, Dennis PB, Pullen N, Pearson RB, Williamson NA, et al. Dual requirement for a newly identified phosphorylation site in p70s6k. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5648–5655. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turck F, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Nagy F. A heat-sensitive Arabidopsis thaliana kinase substitutes for human p70s6k function in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2038–2044. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cruz MC, Goldstein AL, Blankenship J, Del Poeta M, Perfect JR, et al. Rapamycin and less immunosuppressive analogs are toxic to Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans via FKBP12-dependent inhibition of TOR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3162–3170. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3162-3170.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vidalain PO, Boxem M, Ge H, Li S, Vidal M. Increasing specificity in high-throughput yeast two-hybrid experiments. Methods. 2004;32:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Figeys D. Mapping the human protein interactome. Cell Res. 2008;18:716–724. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iyer M, Wu L, Carey M, Wang Y, Smallwood A, Gambhir S. Two-step transcriptional amplification as a method for imaging reporter gene expression using weak promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14595–14600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251551098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griggs DW, Johnston M. Promoter elements determining weak expression of the GAL4 regulatory gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4999–5009. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villalobos V, Naik S, Piwnica-Worms D. Current state of imaging protein-protein interactions in vivo with genetically encoded reporters. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:321–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.