SUMMARY

Background

Deficiencies in granule-bound substances in platelets cause congenital bleeding disorders known as storage pool deficiencies. For disorders such as Gray Platelet syndrome (GPS), in which thrombocytopenia, enlarged platelets, and a paucity of alpha granules are observed, only the clinical and histological states have been defined.

Objectives

In order to understand the molecular defect in GPS, the alpha-granule (α-granule) fraction protein composition from a normal individual was compared with a GPS patient using mass spectrometry (MS).

Methods

Platelet organelles were separated using sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. Proteins from sedimented fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin. Peptides were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem-MS. Mascot was used to determine peptide/protein identification and peptide False Positive Rates. MassSieve was used to generate and compare parsimonious lists of proteins.

Results

Compared with control, the normalized peptide hits (NPH) from soluble, biosynthetic α-granule proteins were markedly decreased or undetected in GPS, whereas the NPH from soluble, endocytosed α-granule proteins were only moderately affected. The NPH from membrane-bound α-granule proteins were similar in normal and GPS, although P-selectin and Glut-3 were slightly decreased, consistent with immuno-electron microscopy in resting platelets. We also identified proteins not previously known to be decreased in GPS, including latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 1 (LTBP-1), a component of the TGF-β complex.

Conclusions

Our results support the existence of “ghost granules” in GPS, point to the basic defect in GPS as failure to incorporate endogenously-synthesized megakaryocytic proteins into α-granules, and identify specific new proteins as α-granule inhabitants.

Keywords: α-granule, Gray Platelet Syndrome, LTBP-1, mass spectrometry, platelet

BACKGROUND

Genetic deficiencies of alpha or dense granules cause congenital bleeding disorders termed storage pool deficiencies (SPDs). Gray Platelet syndrome (GPS) results in deficient or absent α-granules, causing a pale gray appearance of platelets on Wright-stained peripheral blood smears [1]. Electron microscopy shows large, abnormal platelets with small α-granules or empty vacuoles the size of normal α-granules [1–4]. These organelles contain several adhesive proteins involved in hemostasis, as well as glycoproteins active in inflammation, wound healing, and cell–matrix interactions. There are autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant and X-linked types of GPS, but the causative gene (GATA1) has been identified only for the X-linked form [5]. Patients have variable degrees of bleeding problems, and an occasional fatality has been observed. Myelofibrosis of unknown etiology is an important manifestation in GPS [6]. Early immunohistochemical and electron microscopy studies suggest that the α-granule defect in GPS is associated with an inability to transfer cargo proteins to developing α-granules suggesting that the primary defect may not be in the synthesis of α-granule membranes [3, 4, 7].

In order to understand the molecular defect in GPS, we first sought to characterize the protein composition of isolated α-granules from normal platelets using sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation and mass spectrometry (MS) [8]. Of the 219 proteins detected in normal α-granules by MS, 36 were known α-granule proteins and 44 were proposed to be new α-granule proteins [8]. Immuno-electron microscopy (Immuno-EM) confirmed the presence of Scamp2, APLP2, ESAM and LAMA5 in platelet α-granules for the first time [8]. In the present study, we used the same technology to determine the spectrum and amount of known, soluble and membrane-bound α-granule proteins in a GPS patient compared with a normal individual. We also used mass spectrometry to point to new proteins that may be decreased in GPS.

METHODS

Patients

Whole blood was collected from a Gray Platelet Syndrome patient, evaluated at the NIH Clinical Center, under an institutional review board-approved protocol, 76-HG-0238, after written, informed consent. This 51-year-old male patient is the original GPS patient described previously [2]. He had easy bruising since early infancy. He was diagnosed as having thrombocytopenia at 8 years of age, and was followed with a diagnosis of probable idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. His platelet count was decreased to 54 K/μL at age 10 years, and his spleen was removed at age 11. This patient had thrombocytopenia and typical large pale gray platelets, and a platelet count was 94 K/μL. Transmission electron microscopy revealed large platelets with significantly diminished numbers of α-granules. Bone marrow evaluation at NIH showed myelofibrosis. This patient was the only affected individual in his family; the parents’ and brother’s platelets were normal. The Control blood sample was collected from a normal, healthy, adult donor at the NIH Department of Transfusion medicine under an institutional review board-approved protocol, 99-CC-0168, after written informed consent.

Platelet preparation

Whole blood was collected into acid-citrate-dextrose and centrifuged at 800 × g for 3 min to collect platelet-rich plasma. The platelets, separated from plasma using a discontinuous arabinogalactan gradient, were washed with Tyrode’s I buffer (140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 47 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM NaHCO3, 1 mg/mL glucose, adjusted to pH 6.5) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Residual red cells were lysed with 1% ammonium oxalate.

Platelet lysis and organelle fractionation

Platelet fractions were prepared as described previously [8]. Briefly, platelets were re-suspended in 250 mM sucrose and lysed by ultrasonication (Microson ultrasonic cell disruptor, Misonix, Farmingdale, NY, USA). Non-lysed platelets were pelleted by centrifugation at 700 × g for 6 min. The supernatant containing platelet organelles was loaded onto pre-formed, 10 mL, linear sucrose gradients (20–50% sucrose; 60% sucrose cushion). The gradients were centrifuged at 217,000 × g in a Beckman SW 41 Ti rotor for 16 h at 4°C. Nine fractions were collected using careful pipetting from the top. Fractions were transferred to polycarbonate tubes, diluted in 6% sucrose, and centrifuged at 140,000 × g in a Beckman 70.1 Ti rotor for 1 h at 4°C. The pellets were re-suspended in 50 μL Tyrode’s I buffer (pH 6.5) and frozen at −20°C. Protein concentration was determined using the BioRad Protein Assay with BSA as the standard. Fractions were also pelleted and fixed for immuno-electron microscopy.

Chemicals

Formic acid (98%) was purchased from Fluka (Buchs SG, Switzerland). HPLC-grade acetonitrile and methanol were from Burdick & Jackson (Muskegon, MI, USA). Modified porcine trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Larex UF Powder was from Larex, Inc. (White Bear Lake, MN, USA). Complete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets were purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All other chemicals were from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mouse anti-human LTBP-1 (sc-80168) was from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The anti-human glucose transporter-3 (Glut-3) antibody was raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to the last 12 amino acids in the carboxy terminus of the protein [9]. Rabbit anti-human albumin was from Nordic (Tilburg, The Netherlands). Rabbit anti-human fibrinogen was from Dakopatts (Glostrup, Denmark). Rabbit anti-human β-thromboglobulin was previously characterized [10].

Light microscopy

Platelet samples were smeared and dried on glass LM slides and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. Images were acquired with a 63x/1.4 oil DIC Plan-APOCHROMAT objective using a Zeiss AxioVert 200M Inverted light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA), equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam high resolution camera and Zeiss AxioVision 4.5 acquisition software.

Immuno-electron microscopy

Resting platelets were obtained from freshly fixed whole blood which was collected directly from the vein into fixative (1:5 volume ratio in 2.4% paraformaldehyde and 0.24% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). After platelet isolation, the samples were infiltrated in 2.3 M sucrose and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The fractions from the sucrose gradient were fixed in a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and frozen in a similar fashion. Cryosectioning and immunogold labeling were performed according to established procedures[11]. Sections of whole platelets and fractions were viewed in a JEOL 1200CX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Quantification of immunogold labeling was carried-out on 50 randomly-selected platelet cross-sections of three independent immunolabeling experiments. Gold particles were counted over α-granules, plasma membrane (PM) and open canalicular system (OCS) membranes.

Protein separation

Protein samples were reduced with DTT (10x NuPage Sample Reducing Agent, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), solubilized in 2X SDS Protein Gel Solution (Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and heated at 70°C for 3 min in a water bath. For GPS and control, 40 μg total protein was loaded on a 4–12% Novex Tris-Glycine Gel (n=2 experimental replicates each) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with NuPage Antioxidant in the inner chamber and separated at 125 volts for 1.5 h. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 Staining Solution (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and destained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 Destaining Solution.

In-gel digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis

Gel bands were processed as described [8]. Briefly, Bands were excised, destained in 50:50 methanol/0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3), washed in 0.1 M NH4HCO3 and washed in 50:50 acetonitrile/0.1 M NH4HCO3. Bands were shrunk in acetonitrile and dried in an Eppendorf Vacufuge (Eppendorf North America, Westbury, NY, USA). Proteins were reduced with 10 mM DTT in 25 mM NH4HCO3 for 1 h at 56°C, then alkylated with 55 mM iodoacetamide in 25 mM NH4HCO3 for 45 min in the dark at room temperature. Bands were washed with 25 NH4HCO3 and dehydrated with acetonitrile. Gel pieces were re-swelled with 10 ng/μL trypsin in 25 mM NH4HCO3. Digestions were performed overnight in a 37°C water bath. Trypsin digestion cocktail was transferred from each tube into a corresponding labeled tube and sequential peptide extractions were performed on each band using solutions of 5%, 50% and 80% acetonitrile in water, supplemented with 0.1% formic acid. Samples were dried and re-suspended in HPLC mobile phase A (2:97.9:0.1 acetonitrile/water/formic acid) for LC-MS/MS analysis [8].

Peptides were separated and analyzed by a fully automated HPLC-MS system consisting of an Ultimate Nano-HPLC system (LCPackings/Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) connected online to a ThermoElectron LTQ NSI-Ion Trap mass spectrometer (San Jose, CA, USA). The reversed-phase separation conditions, trapping column and separation column were described [8]. The LTQ was operated in positive ion mode with dynamic exclusion set to repeat count = 1, repeat duration = 30, exclusion duration = 60, exclusion mass width low = 0.5 amu, exclusion mass width high = 1.0 amu, expiration count = 2. Spectra were acquired in a data dependent manner with the top five most intense ions in the MS scan selected for MS/MS. A threshold of 3000 was required to trigger MS/MS.

Data searching and output analysis

Raw MS/MS files were submitted to the NIH Mascot [12] Cluster using Mascot Daemon. Data were searched against the Uniprot-Sprot database (updated February 19, 2010), with an automatic decoy search, using Homo sapiens taxonomy, enzymatic cleavage = trypsin, fixed modification = carbamidomethyl (C), variable modification = oxidation (M), monoisotopic mass, peptide tolerance = 1.5 Da, MS/MS tolerance = 0.8 Da, one missed cleavage, charge state = 1+, 2+, and 3+, instrument = ESI-TRAP. For each peptide, Mascot reports a probability-based ion score, defined as −10*log10(P), where P is the absolute probability that the observed match between the experimental data and the database sequence is a random event. Peptide False Discovery Rate (FDR)[13] was calculated by Mascot and is reported in Supplemental Table 1 for each gel band and for the merged gel bands for each experiment.

MassSieve [14] was used to parse the individual gel band results and subsequently concatenate the results from each gel lane to produce minimal, parsimonious lists of proteins [15, 16]. Initially, the MassSieve filter was set to retain only peptides whose individual ion scores met or exceeded their Mascot identity score thresholds at a more conservative p-value (p<0.01) [8]. Total peptide hits per experiment (e.g., per gel lane) were determined and used as the denominator in the normalization calculation described below. Then, the MassSieve filter was set to exclude indeterminate peptides and proteins with fewer than 2 peptide identifications. Peptide and protein level parsimony comparisons were made across GPS and control lanes and preferred proteins [14], which are the minimal number of proteins needed to describe the peptide data, were exported to Excel.

Relative protein abundance between samples was determined using a normalized spectral counting approach [16]. Peptide hits, which are the total number of independent MS/MS spectra assigned to each protein by Mascot, were used.

Normalized Peptide Hits (NPH) were calculated by dividing the number of peptide hits per protein by the total number of peptide hits per experiment (e.g., per gel lane) [16]. The average of this ratio was taken for control (n=2) and GPS (n=2) gel experiments. Gene Ontology annotations of cellular component, molecular function, and biological process were obtained for each protein using STRAP [17]. Proteins categorized by mitochondrial cellular localization were removed from the final list. Equivalent and superset proteins were also removed from the list.

RESULTS

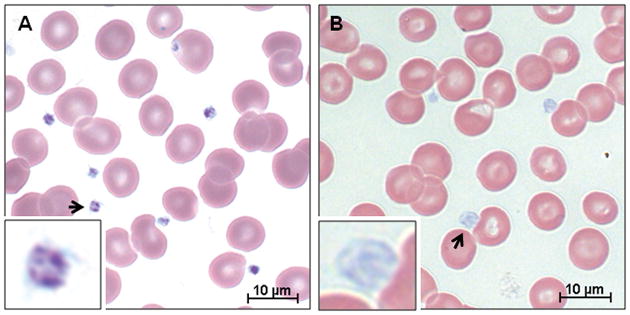

Peripheral blood smears

Analysis of control and GPS platelets revealed major differences in the whole blood smears. Using Wright-Giemsa stain, the normal blood smear showed characteristic darkly-stained platelets (Fig. 1A), whereas the GPS blood smear showed enlarged, pale gray platelets, indicative of GPS (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Blood smears stained with Wright-Giemsa stain.

(A) Normal control. (B) GPS. The normal smear shows typical darkly-stained platelets whereas the patient smear shows enlarged, gray platelets, indicative of GPS (inset).

Separation and characterization of platelet granule fractions

Sucrose gradient fractionation of normal platelet extracts revealed several distinct bands, which were divided into fractions (1–9) for sedimentation by ultracentrifugation. Based upon previous work that identified sucrose fraction 6 from normal controls as enriched in intact α-granules [8], we focused on this fraction for comparison with GPS. Fraction 6 from GPS showed lighter overall band intensity than control. Portions of fraction 6 from control and GPS were fixed and examined by immuno-EM using the α-granule marker glucose transporter-3 (Glut-3). Abundant electron-dense α-granules containing Glut-3 were present in the control sample (Fig. S1A). The corresponding GPS fraction 6 contained electron lucent membranes, which were mostly negative for Glut-3, albeit not exclusively. When present, dense-core α-granules were heavily labeled with Glut-3 (arrowhead in Fig. S1B).

Identification of α-granule proteins by mass spectrometry

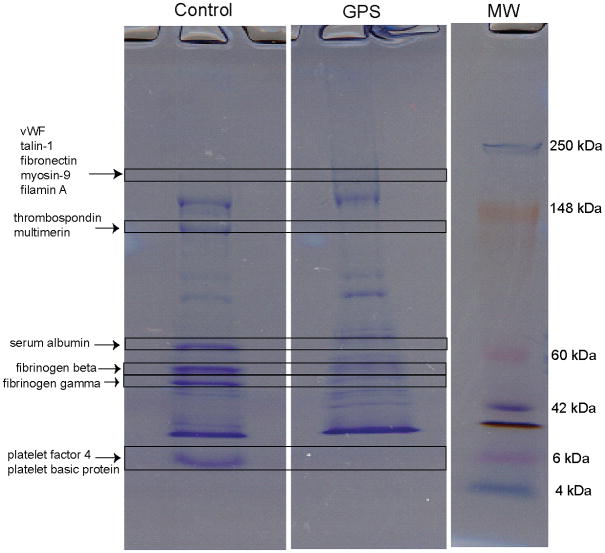

The complex protein mixtures in fraction 6 from control and GPS were separated by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE gel and the resulting tryptic peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS (see Fig. 2). Several known α-granule proteins identified by MS are indicated on the gel.

Figure 2. SDS-PAGE separation of fraction 6 proteins from control and GPS sucrose gradients.

Gels were loaded with 40 μg total protein and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Proteins were reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin. Peptides were extracted and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Each gel band represents many proteins; among them are labeled some relevant platelet α-granule proteins that contribute to the signal. Labels show soluble biosynthetic and endocytosed proteins detected in the control sample. Some proteins were severely reduced or undetected in the corresponding GPS band (e.g. vWF, thrombospondin) whereas other proteins were only moderately affected (e.g. serum albumin, fibrinogen) in the GPS band. See also Supplemental Table 2 and Methods.

The Peptide False Discovery Rate (FDR) (Supplemental Table 1.) determined by Mascot for each gel band at p<0.05 ranged from 0.6–5.37% for the top 21 of 22 gel bands analyzed. The lowest molecular weight (MW) gel band (band 22) in each lane had a high FDR range (4.5–14.7%), most likely due to the fact that the lowest MW gel band contains the fewest number of peptides, meaning the estimation of FDR is less accurate [13]. FDR was then re-calculated for each gel band at p<0.01 and bands 1–21 had values of 0–1.86%. Band 22 in each sample had an FDR range of 3.7–10% at p<0.01. When the gel bands were merged prior to Mascot database searching, the peptide FDR for each lane was <3% at p<0.05 and <1% at p<0.01. By merging the gel bands prior to searching, band 22 peptides become part of the larger dataset and the estimation becomes more accurate. Based on these findings, the MassSieve filter was set to p<0.01 for determination of total peptide hits and for the final Supplemental Table.

The average Normalized Peptide Hits (NPH) for 2 gel replicates was determined for each protein; additional gel replicates were not possible due to insufficient total protein in GPS fraction 6. Parsimonious lists of proteins from each gel experiment were compared. Discrete and differentiable proteins were retained in the final supplemental table; 20 equivalent and superset proteins (histone-related) were removed. Mitochondrial, nuclear and ER-derived proteins were found in both control and GPS samples, most likely as contaminating proteins from the sucrose gradient fractionation step. Because mitochondrial proteins are well annotated in the GO database without much overlap with other localizations, they were removed from the final list, which contains 586 protein identifications. (See Supplemental Table 2.)

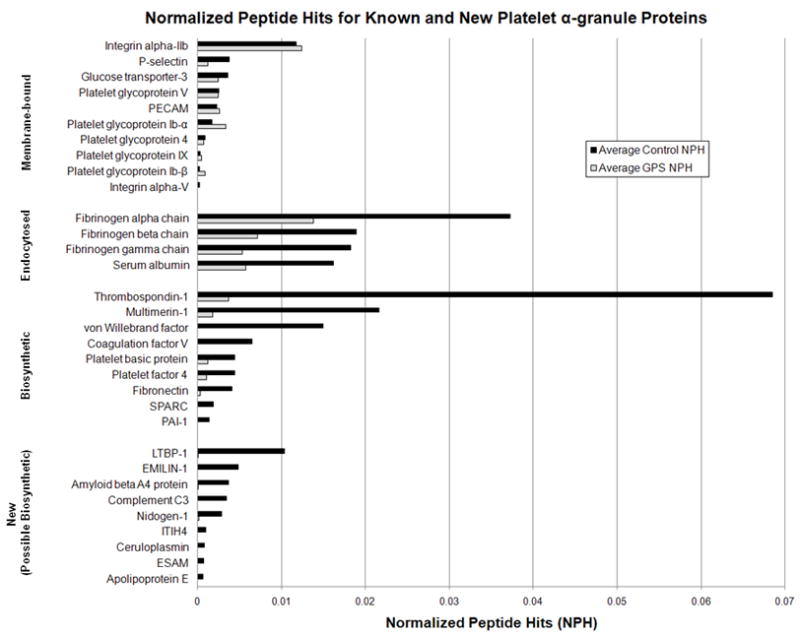

The NPH values for several known α-granule proteins were examined in order to determine if NPH values could be used to compare relative protein abundance between control and GPS samples (see Fig. 3). We found that the NPH from soluble proteins synthesized in the megakaryocyte (MK) were markedly decreased or undetected in GPS fraction 6 compared to normal while the NPH from soluble proteins endocytosed into α-granules were only moderately decreased in GPS platelets compared to normal. The NPH from membrane-bound proteins were approximately the same in GPS as in normal; P-selectin and Glut-3 were slightly decreased whereas PECAM and glycoprotein 1b-α were slightly increased in GPS fraction 6 compared with normal. These NPH findings are consistent with known trends in protein abundance found in the literature.

Figure 3. Average number of normalized peptide hits (NPH) from several known and new α-granule proteins identified in fraction 6 from control and GPS platelets.

Compared with control, the NPH from soluble, biosynthetic proteins was markedly decreased or undetected whereas the NPH from soluble, endocytosed proteins was somewhat decreased in GPS fraction 6. The NPH from membrane-bound proteins was similar in GPS fraction 6 compared with control, though Glut-3 and P-selectin were slightly decreased in GPS. MS analysis revealed additional proteins with decreased NPH in GPS compared with control. These proteins follow NPH trends similar to biosynthetic proteins and are potentially new α-granule proteins.

Further data analysis revealed several proteins with a significantly decreased number of NPH in GPS fraction 6 compared with control (see also Fig. 3). These proteins include the extracellular matrix proteins nidogen-1 and emilin-1, and the secreted proteins latent-TGF-β-binding protein 1S, amyloid beta A4 protein, complement C3, inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4, ceruloplasmin, and apolipoprotein E. These proteins were not previously known to be decreased in GPS α-granules. The NPH trends for these proteins follow those of the known, biosynthetic proteins. In contrast, Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP2, plectin, dynamin, kinesin, AP-1, and clathrin heavy chain had an increased number of NPH in GPS compared with control.

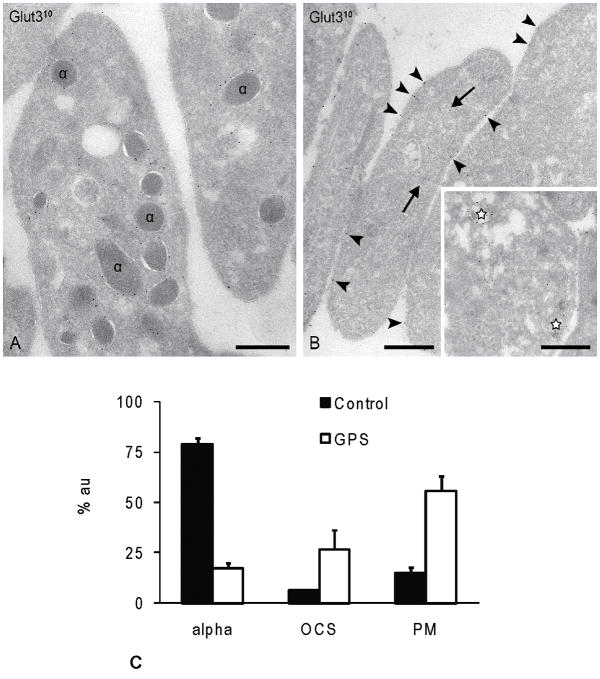

Immuno-electron microscopy of resting whole platelets

In order to confirm the MS findings, we performed immuno-EM on resting whole platelets from a normal control and our GPS patient. First, localization of the known α-granule membrane marker Glut-3 was determined. In control platelets Glut-3 labeling was distributed essentially as described previously [18]. The majority was confined to the α-granule membrane (Fig. 4A), with low levels also present on OCS and PM. In GPS platelets, Glut-3 was predominantly expressed on the cell surface and in the open canalicular system (OCS) (Fig. 4B). Occasional putative α-granules with less densely-packed cargo (stars in Fig. 4B, inset) were also positive for Glut-3. Next, we performed semi-quantitative analysis of three independent labeling experiments (Fig. 4C). In control platelets, the majority (79%) of the gold particles were located on α-granule membranes. The remaining particles were distributed over the PM (15%) and OCS (6%). In contrast, Glut-3 labeling in GPS platelets was predominantly associated with the PM (56%), with 27% distributed over the OCS and just 17% associated with residual α-granule structures. Thus, in GPS platelets a significant shift of Glut-3 towards PM and OCS-like structures in GPS platelets was observed. These findings are in agreement with the MS data showing a decreased, but detectable amount of Glut-3 in GPS fraction 6. Similar results were obtained with P-selectin (data not shown).

Figure 4. Glut-3 immunolabeling and semi-quantitative analysis.

Frozen thin-sections of resting platelets immediately were fixed from whole blood. Immunolabeling for Glut-3 using 10nm protein-A gold. (A) Control platelets. The majority of Glut-3 was confined to the α-granule membrane, with low levels also present on OCS and PM. (B) GPS platelets. Glut-3 was predominantly expressed on the cell surface and in the open canalicular system (OCS) Occasional putative α-granules with less densely-packed cargo (stars, inset) were also positive for Glut-3. (C) Semi-quantitative analysis of the Glut-3 distribution over α-granules, plasma membrane, and OCS structures in control and GPS platelets. Glut-3 is predominantly associated with the cell surface and OCS structures in GPS platelets. Bars, 200nm. % au = % gold; alpha = α-granule; OCS = open canalicular system; PM = plasma membrane.

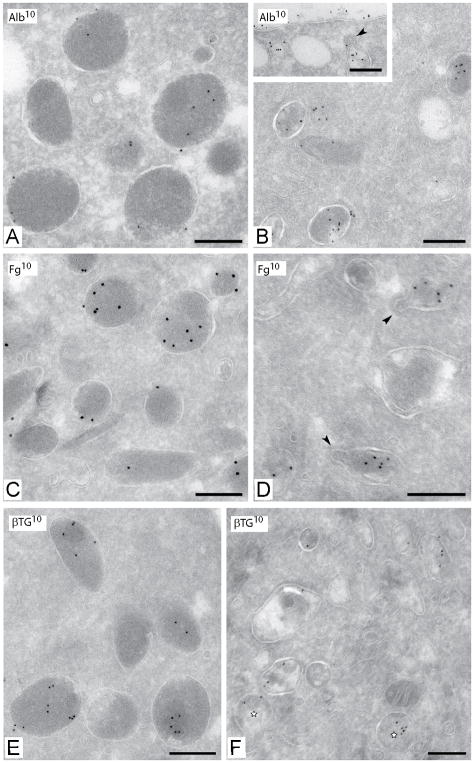

Immuno-EM analysis was also used to validate the MS findings for the known soluble biosynthetic protein β-thromboglobulin (βTG) and the endocytosed α-granule proteins fibrinogen and albumin. βTG and the endocytic markers fibrinogen and albumin were all abundantly expressed in the intact α-granules of control samples. Albumin and fibrinogen were still detected in the GPS platelets and appeared associated with OCS-like structures and with residual α-granules (Fig. 5B, D). βTG was significantly reduced in GPS and was only associated with residual α-granules (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5. Immunolabeling of Control and GPS platelets with known α–granule proteins.

Frozen thin-sections of resting platelets immediately fixed from whole blood. (A, C, E) Control platelets. (B, D, F) GPS platelets. (A,B) Immunolabeling for albumin using 10nm protein gold. Inset in B: clathrin-coated OCS structure (arrowhead) containing albumin. (C,D) Immunolabeling for fibrinogen in clathrin-coated residual α-granule structures. Albumin and fibrinogen are still found in GPS platelets associated with residual α-granules and OCS-like structures. (E,F) Immunolabeling for βTG in control and GPS platelets. βTG was significantly reduced in GPS and only associated with residual α-granules. Bars, 200nm.

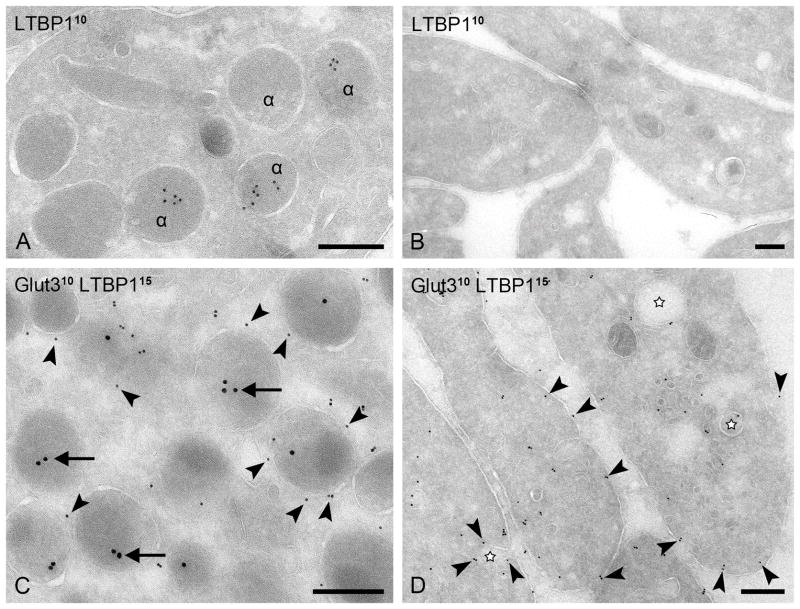

To further validate our MS data, we performed immuno-gold labeling using antibodies to latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 1 (LTBP-1). In control platelets, LTBP-1 appeared exclusively localized to the lumen of the α-granules (Fig. 6A), whereas in GPS platelets, LTBP-1 labeling was absent (Fig. 6B). Immuno-gold double-labeling confirmed that LTBP-1 is localized within Glut-3-positive α-granules in control platelets (Fig. 6C), and is absent from residual Glut-3 positive membrane structures (marked with an asterisk) in GPS platelets (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. Simultaneous demonstration of LTBP-1 and Glut-3.

(A, C) Control platelets. (B, D) GPS platelets. (A, B) Immunogold labeling using mouse anti-LTBP-1 antibody and 10nm protein-A gold. LTBP-1 is localized in normal platelet α-granules but is absent in GPS. (C, D) Immunogold double-labeling of Glut-3 using 10nm protein-A gold (arrowheads) and LTBP-1 (arrows) using 15nm protein A-gold. α, α-granules; LTBP-1 is localized within Glut-3-positive α-granules in control platelets but it is absent from residual Glut-3 positive OCS-like membrane structures (marked with an asterisk) in GPS platelets. Bars, 200 nm.

DISCUSSION

Gray Platelet Syndrome (GPS) is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by thrombocytopenia and large, abnormal platelets lacking alpha granules and their constituents. Evidence suggests that the molecular defect may consist of improper sorting of proteins into the maturing alpha granules in precursor MKs. In a recent study we described the protein complement of α-granules isolated from normal human platelets using sucrose gradient fractionation and MS [8]; we now investigate a patient with Gray Platelet Syndrome. Overall, the MS data indicate that synthesized and endocytosed α-granule proteins are differentially affected in GPS platelets, support the existence of so-called “ghost granules” in GPS platelets [4, 19], and point to intracellular targeting of endogenously-synthesized proteins as the basic defect in GPS.

Protein characterization of the α-granule-enriched fraction (fraction 6) from normal control platelets and GPS platelets by MS and immuno-EM showed that α-granules are not completely absent from GPS platelets, but are significantly reduced, as previously reported [4]. In fact, validation by immuno-EM revealed that intact dense-core α-granules are still sparsely present in the GPS platelets. The majority of granules exhibit high variability in matrix density and include complete electron-lucent profiles resembling OCS vacuoles. While the lack of a high protein content influences the sedimentation of GPS α-granules on a sucrose gradient, GPS platelets nevertheless contain a population of α-granule membranes that sediment in fraction 6, largely by virtue of their exogenous protein content. These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that even normal platelets contain α-granule subsets with different protein compositions and different release triggers [20, 21]. Further research will be required to identify whether such α-granule subtypes migrate differently in sucrose gradients. Because of lack of sufficient quantities of purified membranes within other GPS fractions, additional MS could not be performed on those fractions.

MS analysis of fraction 6 proteins revealed that NPH values for several known α-granule proteins reflected the expected relative protein abundance in normal and GPS α-granules, based upon literature reports. For example, biosynthetic α-granule proteins such as von Willebrand factor [4, 19] showed a dearth of peptides in our GPS patient samples, reflecting the virtual absence of these proteins in GPS platelets. Other soluble biosynthetic proteins such as platelet factor 4, βTG [4, 19], multimerin [4, 22], and fibronectin [4, 19] were markedly reduced or undetectable in GPS sucrose fraction 6. By comparison, the NPH from soluble proteins of endocytic origin, such as albumin [4, 19] and fibrinogen [4, 19], were only moderately affected in GPS platelets; this was also validated by immuno-EM. The NPH from α-granule membrane-bound proteins was similar in control and GPS, although Glut-3 and P-selectin [4] were slightly decreased in GPS compared with control. Validation of the Glut-3 results was performed by immuno-EM. In control platelets the majority of the Glut-3 was located on the α-granule membrane with lower amounts also found on the PM and OCS, in agreement with previous studies [18]. However, in GPS platelets, a larger proportion of Glut-3 was expressed on the cell surface and on membranes of the OCS rather than on the α-granule membranes. This indicates that at least a portion of the α-granule membrane proteins are mis-targeted to the cell surface and OCS in GPS platelets. Part of the OCS-like structures in GPS may also represent α-granule ghost membranes. Indeed, in GPS platelets, we detected OCS-like membranes that contained low amounts of electron-dense content (Fig. 4B). In GPS, a higher proportion of these membranes may end up in fraction 6, as reflected by the slightly higher GPIb levels in GPS.

Further analysis of the MS data revealed a group of secreted and extracellular matrix proteins with NPH values that were significantly decreased in GPS fraction 6 compared to control (Fig. 3). Among them, complement-3, amyloid beta A4, nidogen, and LTBP-1 were detected in the releasate of normal human platelets following stimulation with thrombin [23]. Deficiency of these proteins in GPS suggests that they are either not synthesized in GPS MK’s or that they are not packaged correctly and are constitutively released during MK maturation. If these proteins were endocytosed, we would expect the NPH trends in GPS to be closer to those of known endocytic proteins like albumin or fibrinogen. Therefore, we speculate that these proteins are of biosynthetic origin.

Of particular interest is that several of the new proteins with decreased NPH in GPS are related to TGF-β bioavailability. TGF-β is secreted by many cell types as a large latent complex composed of 3 subunits: TGF-β, TGF-β pro-peptide, and the latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP) [24]. It has been localized to platelet α-granules and is involved in the modulation of the wound healing response [4]. Emilin-1 is a regulator of TGF-β processing and activation; it plays a role in the pathogenesis of hypertension and may be important in other conditions such as atherosclerosis, inflammation, tissue repair, fibrosis, and cancer [25]. ITIH4 (inter-alpha (globulin) inhibitor H4) is part of a family of protease inhibitors whose main function is stabilization of the extracellular matrix [26] and it may be an important mediator of hepatocarcinogenesis [27].

LTBP-1 co-localized with Glut-3 to α-granules in control platelets, but was undetectable by immuno-EM in GPS platelets even though residual “ghosts” and dense-core Glut-3-positive granules were present (Fig. 6). These results validate the dearth of peptides detected in GPS fraction 6 by MS. We suggest that in GPS, LTBP-1 is either mis-targeted and/or packaged incorrectly into platelet α-granules. LTBP-1 is an extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoprotein that is associated with the latent TGF-β-1 complex in human platelets [28]. Lack of proper LTBP-1 packaging during MK differentiation may result in constitutively active TGF-β [29]. Secretion of active TGF-β into the bone marrow could then cause myelofibrosis in GPS. Further studies are required to address this point. Alternatively, LTBP-1 may exert effects independently of those associated with TGF-β, for example, as a structural matrix protein. [30]

Other proteins had an increased number of NPH in GPS compared with control. For example, IQGAP2, a rac1/cdc42 effector protein, was only detected in GPS. IQGAP2 is expressed in human platelets and functions as a thrombin-regulated scaffolding protein in platelet activation [31]. Also, proteins such as plectin, dynamin, kinesin, AP-1, and clathrin heavy chain were increased in GPS fraction 6. Several of these proteins are involved in intracellular trafficking and secretion, so one might consider if mis-targeting of cargo could be a result of changes in the intracellular trafficking pathways, and lead to a shift from storage-based regulated secretion (α-granules) towards constitutive secretion in GPS. Alternatively, an increased number of some of these proteins could be caused by contamination of the GPS fraction with remnants of OCS or plasma membrane.

We are aware that there are limitations to this study. First, GPS is a rare disease and it was difficult to obtain a large patient/control series; a larger cohort of patients will be needed for broader statistical validation of the detected peptides. Next, proteins of mitochondrial[8], ribosomal[32], endoplasmic reticulum (DTS), and nuclear[33] origin were found in both control and GPS fraction 6 to a similar extent. This contamination may be due to remaining proteins from precursor MK’s, multiple protein localization assignments by Gene Ontology, or the presence of other membrane components from the sucrose gradient fractionation. Additional purification steps of fraction 6 may decrease this problem. Finally, phosphorylation or other post-translational modifications were not selected or searched for in our work-flow, so further studies are needed to obtain a more comprehensive modified-peptide catalog. Nonetheless, we hope this peptide catalog will provide a useful resource for the platelet community.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that a proteomic/MS workflow can be used to study the relative abundance of α-granule proteins in normal and GPS platelet organelle fractions by using several known α-granule proteins as a model. Soluble, biosynthetic cargo proteins were severely reduced or undetected in GPS platelets, whereas the packaging of soluble, endocytic cargo was only moderately affected. Using immuno-EM we confirmed that the endocytic cargo proteins fibrinogen and albumin remain detectable in GPS platelets. Immuno-EM also confirmed the α-granule localization of the cargo protein LTBP-1 in normal but not GPS platelets, confirming that LTBP-1 is an α-granule protein. Our MS approach may be employed to characterize the composition of organelles in patients with other SPDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute and the NIH Clinical Center (Clinical trials identifier NCT00369421). We thank Dr. Susan F. Leitman, M.D., Department of Transfusion Medicine, NIH Clinical Center, for control blood samples (Clinical trials identifier NCT00001846), Ms. H. Dorward for assistance in obtaining light microscope images, Ms. S. van Dijk for the immuno-EM work, and Dr. S. Markey and Dr. M. McFarland for helpful discussions regarding proteomic data normalization.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SPD

storage pool deficiency

- GPS

Gray Platelet Syndrome

- MS

mass spectrometry

- α-granule

alpha granule

- immuno-EM

immuno-electron microscopy

- Scamp2

secretory carrier membrane protein 2

- APLP2

amyloid-like protein 2

- ESAM

endothelial cell-selective adhesion molecule

- LAMA5

laminin alpha-5 chain

- PM

plasma membrane

- OCS

open canalicular system

- Glut-3

glucose transporter-3

- LTBP-1

latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 1

- MK

megakaryocyte

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

D. M. Maynard performed the platelet preparation, sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation and mass spectrometry experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

H. F.G. Heijnen performed the immuno-EM experiments, analyzed the EM data, and assisted in the preparation of the figures and manuscript.

W. A. Gahl is the Principle Investigator of the laboratory. He provided expertise in sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, assisted in preparation of figures, and wrote the manuscript.

M. Gunay-Aygun recruited the GPS patient and evaluated him at the NIH Clinical Center, arranged for the blood draws, evaluated blood smears, and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Smith MP, Cramer EM, Savidge GF. Megakaryocytes and platelets in alpha-granule disorders. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1997;10:125–48. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(97)80054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raccuglia G. Gray platelet syndrome. A variety of qualitative platelet disorder. The American journal of medicine. 1971;51:818–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White JG. Ultrastructural studies of the gray platelet syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1979;95:445–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison P, Cramer EM. Platelet alpha-granules. Blood reviews. 1993;7:52–62. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(93)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tubman VN, Levine JE, Campagna DR, Monahan-Earley R, Dvorak AM, Neufeld EJ, Fleming MD. X-linked gray platelet syndrome due to a GATA1 Arg216Gln mutation. Blood. 2007;109:3297–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falik-Zaccai TC, Anikster Y, Rivera CE, Horne MK, 3rd, Schliamser L, Phornphutkul C, Attias D, Hyman T, White JG, Gahl WA. A new genetic isolate of gray platelet syndrome (GPS): clinical, cellular, and hematologic characteristics. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:303–13. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breton-Gorius J, Vainchenker W, Nurden A, Levy-Toledano S, Caen J. Defective alpha-granule production in megakaryocytes from gray platelet syndrome: ultrastructural studies of bone marrow cells and megakaryocytes growing in culture from blood precursors. The American journal of pathology. 1981;102:10–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maynard DM, Heijnen HF, Horne MK, White JG, Gahl WA. Proteomic analysis of platelet alpha-granules using mass spectrometry. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1945–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris DS, Slot JW, Geuze HJ, James DE. Polarized distribution of glucose transporter isoforms in Caco-2 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:7556–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sander HJ, Slot JW, Bouma BN, Bolhuis PA, Pepper DS, Sixma JJ. Immunocytochemical localization of fibrinogen, platelet factor 4, and beta thromboglobulin in thin frozen sections of human blood platelets. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1983;72:1277–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI111084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heijnen HF, Schiel AE, Fijnheer R, Geuze HJ, Sixma JJ. Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha-granules. Blood. 1999;94:3791–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nature methods. 2007;4:207–14. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slotta DJ, McFarland MA, Makusky SJ, Markey SP. Abstract Number 157. 55th ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; June 3–7, 2007; Indianapolis. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang X, Dondeti V, Dezube R, Maynard DM, Geer LY, Epstein J, Chen X, Markey SP, Kowalak JA. DBParser: web-based software for shotgun proteomic data analyses. Journal of proteome research. 2004;3:1002–8. doi: 10.1021/pr049920x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFarland MA, Ellis CE, Markey SP, Nussbaum RL. Proteomics analysis identifies phosphorylation-dependent alpha-synuclein protein interactions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2123–37. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800116-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia VN, Perlman DH, Costello CE, McComb ME. Software Tool for Researching Annotations of Proteins: Open-Source Protein Annotation Software with Data Visualization. Analytical chemistry. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ac901335x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heijnen HF, Oorschot V, Sixma JJ, Slot JW, James DE. Thrombin stimulates glucose transport in human platelets via the translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT-3 from alpha-granules to the cell surface. The Journal of cell biology. 1997;138:323–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurden AT, Nurden P. The gray platelet syndrome: clinical spectrum of the disease. Blood reviews. 2007;21:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Italiano JE, Jr, Richardson JL, Patel-Hett S, Battinelli E, Zaslavsky A, Short S, Ryeom S, Folkman J, Klement GL. Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: pro- and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet alpha granules and differentially released. Blood. 2008;111:1227–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sehgal S, Storrie B. Evidence that differential packaging of the major platelet granule proteins von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen can support their differential release. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2009–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeimy SB, Tasneem S, Cramer EM, Hayward CP. Multimerin 1. Platelets. 2008;19:83–95. doi: 10.1080/09537100701832157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coppinger JA, Cagney G, Toomey S, Kislinger T, Belton O, McRedmond JP, Cahill DJ, Emili A, Fitzgerald DJ, Maguire PB. Characterization of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to localization of novel platelet proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2004;103:2096–104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunes I, Gleizes PE, Metz CN, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein domains involved in activation and transglutaminase-dependent cross-linking of latent transforming growth factor-beta. The Journal of cell biology. 1997;136:1151–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zacchigna L, Vecchione C, Notte A, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Maretto S, Cifelli G, Ferrari A, Maffei A, Fabbro C, Braghetta P, Marino G, Selvetella G, Aretini A, Colonnese C, Bettarini U, Russo G, Soligo S, Adorno M, Bonaldo P, et al. Emilin1 links TGF-beta maturation to blood pressure homeostasis. Cell. 2006;124:929–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamm A, Veeck J, Bektas N, Wild PJ, Hartmann A, Heindrichs U, Kristiansen G, Werbowetski-Ogilvie T, Del Maestro R, Knuechel R, Dahl E. Frequent expression loss of Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain (ITIH) genes in multiple human solid tumors: a systematic expression analysis. BMC cancer. 2008;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang Y, Kitisin K, Jogunoori W, Li C, Deng CX, Mueller SC, Ressom HW, Rashid A, He AR, Mendelson JS, Jessup JM, Shetty K, Zasloff M, Mishra B, Reddy EP, Johnson L, Mishra L. Progenitor/stem cells give rise to liver cancer due to aberrant TGF-beta and IL-6 signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:2445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705395105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazono K, Hellman U, Wernstedt C, Heldin CH. Latent high molecular weight complex of transforming growth factor beta 1. Purification from human platelets and structural characterization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263:6407–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kogawa K, Mogi Y, Morii K, Takimoto R, Niitsu Y. TGF-beta and platelet. [Rinsho ketsueki] The Japanese journal of clinical hematology. 1994;35:370–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oklu R, Hesketh R. The latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein (LTBP) family. The Biochemical journal. 2000;352(Pt 3):601–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt VA, Scudder L, Devoe CE, Bernards A, Cupit LD, Bahou WF. IQGAP2 functions as a GTP-dependent effector protein in thrombin-induced platelet cytoskeletal reorganization. Blood. 2003;101:3021–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Signal-dependent protein synthesis by activated platelets: new pathways to altered phenotype and function. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:s17–24. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahedi RP, Lewandrowski U, Wiesner J, Wortelkamp S, Moebius J, Schutz C, Walter U, Gambaryan S, Sickmann A. Phosphoproteome of resting human platelets. Journal of proteome research. 2008;7:526–34. doi: 10.1021/pr0704130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.