Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis is regarded as one of the risk factors of periodontitis. P. gingivalis exhibits a wide variety of genotypes. Many insertion sequences (ISs), located in their chromosomes, made P. gingivalis differentiate into virulent and avirulent strains. In this research, we investigated the prevalence of P. gingivalis in the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) among periodontitis patients from Zhenjiang, China, detected the P. gingivalis rag locus distributions by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and analyzed the origin of the P. gingivalis rag locus based on evolution. There were three rag locus variants co-existing in Zhenjiang. The results showed that the rag locus may be associated with severe periodontitis. This work also firstly ascertained that the rag locus might arise, in theory, from Bacteroides sp. via horizontal gene transfer.

Introduction

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium and is considered as a major etiological agent in destructive periodontal diseases [1, 2]. It is frequently detected in a high ratio from severely inflamed subgingival lesions, whereas it may also be isolated from the healthy population at a very lower percentage, and these P. gingivalis constituted a significant proportion of the oral microflora. Previous studies have also shown phenotypic differences in the pathogenicity of strains of P. gingivalis in animal models [3] and in humans [4]. Therefore, P. gingivalis might be an important potential pathogen [5]. Recently, DNA fingerprinting and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis have confirmed that the highly virulent P. gingivalis isolates always carry an rag locus, whereas the avirulent strain does not contain the rag locus [6–8].

The rag locus of virulent P. gingivalis encodes RagA (receptor antigen gene A), a 115-kDa outer membrane protein with features of a TonB-dependent receptor, and RagB, a 55-kDa antigen which makes periodontal patients induce an elevated immunoglobulin G response. The RagA and RagB form a putative co-distribution and co-transcription complexes on the surface of P. gingivalis. The complexes constitute a membrane transporter system, which involves the uptake or recognition of a specific carbohydrate or glycoprotein [9–11]. Four rag locus variants have been detected from periodontal patients [2]. The rag locus has three characteristics: (1) the locus has a lower G+C content compared with the average values (48%) of the complete genome; (2) there is an insertion sequence (IS) 1126 with 1,338 bp (IS1126, now known as ISPg1), located upstream of the rag locus and flanked by 12-bp inverted repeats, which is a mobile element that generates a 5-bp target site duplication [12] and contains a single open reading frame (ORF) encoding the transposase which belongs to the IS5 family [13]; (3) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Southern blots results indicate that the rag locus has a restricted distribution within the species (only existing in virulent genotypes); the rag locus is also amplified from the subgingival samples of undetected P. gingivalis. The characteristics mentioned above make the experts speculate that the rag locus has arisen from exogenous genes and is obtained via horizontal gene transfer, and that the rag locus may represent a pathogenicity island in P. gingivalis. However, so far, no report has indicated from where the rag locus arises.

Since from where the rag locus arises is still unknown, the present work was to investigate the prevalence of P. gingivalis in the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) of periodontitis patients from Zhenjiang, China, to detect the rag locus distributions among periodontitis patients infected by P. gingivalis using multiplex PCR, and to analyze the origin of the P. gingivalis rag locus based on evolution.

Materials and methods

Subjects, selection of sites, and sampling and DNA extraction

A total of 110 GCF samples were obtained from 110 patients (58 female and 52 male, aged between 15 and 68 years) going to hospital for periodontal diseases at the First Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University, China. Patients were screened for periodontal diseases by radiographic evidence of bone loss, or with visible plaque, marginal bleeding, bleeding on probing (BOP), and clinical attachment loss (CAL) and periodontal probing depth (PD) ≥4 mm at two or more sites [14, 15]. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, smoking, and systemic antimicrobial/anti-inflammatory drug therapy within 6 months before the baseline visit. The 110 patients were classified by the 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions [16, 17]: 57 patients were localized chronic periodontitis, 33 were generalized periodontitis, and 20 were necrotizing periodontal diseases (three patients were accompanied with diabetes and five patients had cardiovascular disease). The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave informed consent and the research protocol was approved by the Committee for Ethical Affairs of Jiangsu University.

GCF samples were obtained from the two deepest periodontal pockets in the maxilla according to Rüdin et al’s technique [18]. Before sampling, the respective site was cleaned by cotton rolls; a gentle air stream of 5-s duration with a 90° angle to the tooth axis was used and supragingival plaque was eliminated. Standardized paper strips were inserted 1 mm into the sulcus and held for 30 s. Papers with blood contamination were discarded. To avoid evaporation, paper strips with GCF were immediately put into a sterile Eppendorf tube and stored at −20°C until laboratory analysis.

The isolates in the DNA were extracted by the boiling lysis method [19]. The templates were prepared by suspending in 200 mL of sterile water, followed by boiling for 10 min and centrifuging for 3 min.

PCR-detected P. gingivalis and multiplex PCR amplification of rag locus genes

The 16S rRNA specific primers were used to detect P. gingivalis and four different rag locus variants primers were used to amplify the rag locus among GCF samples containing P. gingivalis by multiplex PCR; the primers are listed in Table 1 [2, 20]. PCR assays were performed in volumes of 15 μl under the following conditions: 1.5 μl 10 × PCR buffer (Mg2+), 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.1 μM of primers, and 1.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Biotechnology [Dalian] Co., Ltd.) for 10 min at 94°C for 35 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 50°C (for 16S rRNA) and 54°C (for the rag locus), and 1 min at 72°C, with a final step of 10 min at 72°C for standard PCR assays.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| No. | Primers | Sequences | Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16S rRNAF | TGT AGA TGA CTG ATGGTG AAA ACC | 197 bp |

| 2 | 16S rRNAR | ACG TCA TCC CCA CCT TCC TC | |

| 3 | rag1F | CGC GAC CCC GAA GGA AAA GAT T | 628 bp |

| 4 | rag1R | CAC GGC TCA CAT AAA GAA CGC T | |

| 5 | rag2F | GCT TTG CCG CTT GTG ACT TGG | 979 bp |

| 6 | rag2R | CCA CCGTCA CCG TTC ACC TTG | |

| 7 | rag3F | CCG GAAGAT AAG GCC AAG AAA GA | 422 bp |

| 8 | rag3R | ACG CCA ATT CGC CAA AGCT | |

| 9 | rag4F | CCG GAT GGA AGT GAT GAACAG A | 738 bp |

| 10 | rag4R | CGC GGT AAA CCT CAG CAA ATT |

Databases and search strategies

A comprehensive search by PSI-BLAST was performed in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) protein database (Reference proteins, RefSeq proteins) using the published ragA1 and ragB1 proteins of P. gingivalis as query sequences. The cutoff values were e-100 for ragA1 and e-10 for ragB1, respectively. The redundant sequences were removed by the DAMBE program, and the nucleotide sequences were also retrieved from GenBank.

Additionally, the function-similar proteins of the rag locus were also retrieved from GenBank, and the similar proteins included hemin/hemoglobin receptor protein (HmuR), TonB-linked adhesin (Tla) of P. gingivalis, TonB-dependent colicin I receptor (CirA) of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica [9, 21], and the lactoferrin and transferrin binding systems in Neisseria and Haemophilus species (TBP2 and LBP2), P. gingivalis orf3, Vibrio cholerae-IS1358, and E. coli orfH. These similar proteins were used to analyze the gene characteristics.

Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were performed using the ClustalX package, and then the results were manually corrected. All alignment gap sites were eliminated before phylogenetic analyses. The phylogenetic trees were reconstructed with the neighbor-joining (NJ) and minimum evolution (ME) methods implemented in MEGA4.0. The bootstrap values were estimated with 1,000 replications. Multiple sequence alignments were also carried out between the rag locus and highly homologous sequences by ClustalX in order to further identify conserved protein motifs. The alignments were shaded by the BOXSHADE program (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/BOX_form.html).

Tests for selection

To test whether the rag locus was evolving neutrally, we aligned the nucleotide sequences and then performed two likelihood ratio tests. Firstly, we compared a model in which all branches had the same dN/dS ratio of 1, in which each branch had its own ratio, to determine whether it was appropriate to use branch-specific tests for selection. As the free-ratio model was a significantly better fit to the data (P > 0.0001), we then performed a second set of tests, comparing a model in which the dN/dS ratio was fixed to 1 with a model in which the dN/dS values of all branches were freely estimated. Model likelihoods were estimated using PAML [22].

Results

The prevalence of P. gingivalis and four rag locus variant gene distributions

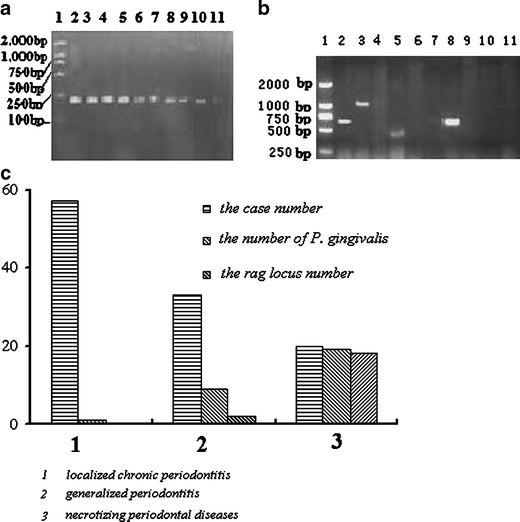

We detected 29 P. gingivalis from 110 GCF samples, one from 57 cases of localized chronic periodontitis, nine from 33 generalized chronic periodontitis patients, and 19 from 20 necrotizing periodontal patients. Among the 29 GCF samples containing P. gingivalis, only 19 cases were amplified from the rag locus genes (ten to rag1, six to rag2, and three to rag3), while rag4 was undetected. Among the 19 cases containing the rag locus, 18 cases were amplified from necrotizing periodontal patients and one from a generalized chronic periodontitis patient. In particular, three patients were accompanied with diabetes and five patients who suffered from cardiovascular diseases also amplified the rag locus, and all of the 19 cases were from at least three sites with a PD of 8 to 10 mm, accompanying clearly visible plaque or BOP and CAL, whereas none of the localized chronic periodontitis patients amplified the rag locus and the PD of the localized chronic periodontitis patients was normally between 4–6 mm (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1a–c.

The prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and four rag locus variant gene distributions. a Agarose gel electrophoresis image of P. gingivalis detection. Lane 1 marker, lane 2 positive control, lane 11 negative control, lanes 3–10 samples. b Image of four rag locus variants gene distributions. Lane 1 marker, lane 2 positive control, lane 11 negative control, lanes 3–10 were samples. c Case numbers of varying degrees of periodontitis, the number of P. gingivalis detected in different periodontitis patients, and the four rag locus variant gene distributions

Phylogenetic analysis

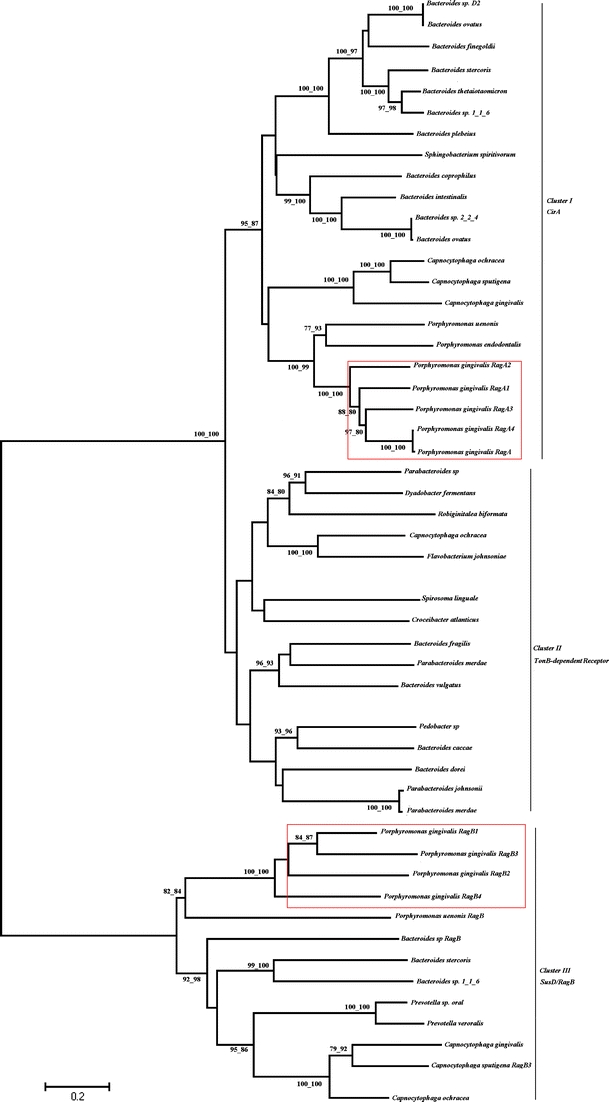

A total of 153 homologous amino acid sequences were retrieved from the RefSeq proteins. The abundant sequences were removed by the DAMBE program and a total 50 protein sequences were included in the final dataset. In order to determine the evolutionary relationships between the P. gingivalis rag locus and homologous sequences, the phylogenetic trees were reconstructed by two different methods (ME and NJ methods) with high bootstrap values. There were three major clusters (I, II, and III), which were statistically supported (Fig. 2). Cluster I mainly included Bacteroides sp. TonB-dependent receptor (SusC/CirA), P. gingivalis ragA, Porphyromonas sp ragA, and Capnocytophaga sp. TonB-dependent receptor; cluster II was constituted of TonB-dependent receptor of Parabacteroides sp., Dyadobacter fermentans, Robiginitalea biformata, Capnocytophaga ochracea, Flavobacterium johnsoniae, Croceibacter atlanticus, Bacteroides sp., Dyadobacter fermentans, and Parabacteroides sp.; and P. gingivalis ragB, Porphyromonas sp. ragB and SusD of Prevotella sp., Bacteroides sp., and Capnocytophaga sp. were involved in the cluster III. This tree showed that branches 1 and 2 in cluster I were the paralogy, and in the cluster III, the two branches were also paralogy. The ragA was highly similar to the TonB-dependent receptor of Bacteroides sp., and ragB was analogous to ragB/SusD of Prevotella sp., Bacteroides sp., and Capnocytophaga sp., respectively.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship between the P. gingivalis ragA/B and highly homologous protein sequences

Analysis of G+C content

The G+C contents of the rag locus, homologous genes, and function-similar genes were analyzed by MEGA4.0 (Table 2). From this table, we could divide these gene sequences into three clusters: lower G+C contents (<40%), moderate (between 40% and 50%), and higher G+C contents (>50%). The P. gingivalis rag locus gene G+C contents were close to Bacteroides sp. Sus.

Table 2.

G+C contents of the rag locus, homologous genes, and function-similar sequences

| Strains | Encode protein | T (%) | C (%) | A (%) | G (%) | G+C (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavobacterium sp. | TonB-dependent receptor | 31.7 | 16.4 | 34.9 | 16.9 | 33.3 |

| Croceibacter sp. | TonB | 35.1 | 20.4 | 29.2 | 15.3 | 35.7 |

| H. influenza | TBP2 | 36.3 | 18.5 | 27.4 | 17.8 | 36.3 |

| Haemophilus | TonB-dependent receptor | 34.4 | 20 | 27.4 | 18.2 | 38.2 |

| Capnocytophaga sp. | TonB-dependent receptor | 31.3 | 20.2 | 28.8 | 20.7 | 40.9 |

| E. coli | orfH | 25.8 | 17.6 | 32.5 | 24.2 | 41.8 |

| V. cholerae | IS1358 | 27.9 | 17.9 | 29.9 | 24.3 | 42.2 |

| P. gingivalis | orf3 | 31 | 20.8 | 25.8 | 22.3 | 43.1 |

| P. gingivalis | RagB | 29.4 | 19.5 | 27 | 23.9 | 43.4 |

| Bacteroides sp. | SusC | 28.0 | 23.5 | 26.5 | 22.0 | 43.5 |

| P. gingivalis | RagA | 29 | 20.5 | 26.7 | 23.9 | 44.4 |

| Parabacteroides | TonB-dependent receptor | 27 | 19.8 | 26.9 | 26.3 | 46.1 |

| N. meningitidis | LBP2 | 31.5 | 25.4 | 22.1 | 20.9 | 46.3 |

| P. gingivalis | hmuR | 26.2 | 24.8 | 27.2 | 21.9 | 46.7 |

| N. meningitidis | TBP2 | 20.2 | 23 | 32.4 | 24.4 | 47.4 |

| P. gingivalis | hemR | 26.8 | 25.2 | 25.8 | 22.2 | 47.4 |

| P. gingivalis | tla | 24.2 | 24.6 | 26.7 | 24.4 | 49 |

| E. coli | CirA | 21.5 | 24.9 | 26.2 | 27.3 | 52.2 |

| Robiginitalea sp. | TonB | 26.7 | 29.6 | 20.1 | 23.5 | 53.1 |

| Salmonella enterica | CirA | 20.8 | 25.8 | 24.6 | 28.8 | 54.6 |

Multiple alignments of the rag locus and Sus

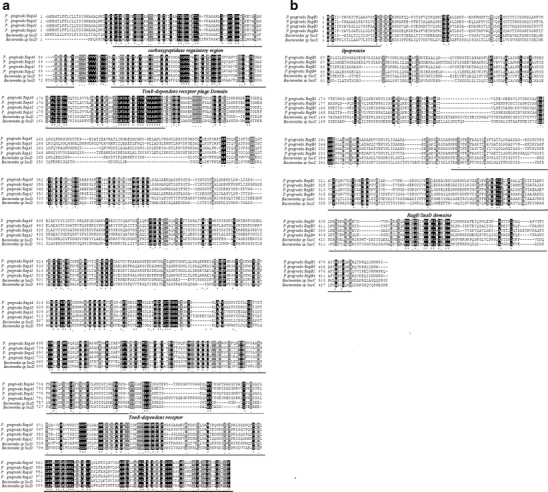

The P. gingivalis rag locus and Bacteroides sp. Sus were aligned for further evolutionary analysis (Fig. 3). The ragA and SusC proteins had three domains: the carboxypeptidase regulatory region, TonB-dependent receptor plug Domain, TonB-dependent receptor (also named TonB box I, box II, and box III), and the ragB and SusD were also constituted of two domains, lipoprotein and RagB/SusD. All of these domains are shown in Fig 3. As shown in Fig. 3a, the RagA motifs generally showed a good match to the three domains of Bacteroides sp. SusC, for example, P××GA×××V×G×TT×G××TD×DG×F×LS at the TonB box I; LKDA××T×IYG×RA×NGV at the TonB box II. However, the amino acids were often substituted in other domains. There are also some conserved positions in lipoprotein and RagB/SusD domains indicated in Fig. 3b. Nevertheless, the major positions in other domains showed far less conservation.

Fig. 3a, b.

Comparison of the P. gingivalis rag locus with Bacteroides Sus. a, b Multiple amino acid sequences alignment between the P. gingivalis RagA locus with Bacteroides SusC. The asterisks indicate positions within the proteins that were identical. The carboxypeptidase regulatory region, TonB-dependent receptor plug Domain, TonB-dependent receptor, lipoprotein, and RagB/SusD domains are shown

Selection

We investigated whether the rag locus was evolving neutrally and examined the ratios of nonsynonymous to synonymous changes (dN/dS) along each branch of the tree. The ragA locus had a dN/dS of 0.23, and the ragB locus had a dN/dS of 0.19. Both these values were significantly lower than a neutral dN/dS of 1 (P > 0.0001, likelihood ratio test, Bonferroni correction for multiple tests), which indicated that these genes were probably evolving under long-term purifying selection.

Discussion

Though the exact roles that P. gingivalis played in the initiation and progression of periodontitis remain unclear, it is definite that P. gingivalis has been known to be a risk factor for periodontitis. Furthermore, accumulated evidence shows that an infection with P. gingivalis might predispose an individual to suffer from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and the delivery of preterm infants [23–26]. All of these factors highlighted the importance of preventing infection from this bacterium. In this respect, information on the virulent factors and genotype of P. gingivalis among individuals becomes important for developing treatment strategies and preventing the transmission of the pathogen to uninfected individuals [12]. Previous researches stated that P. gingivalis produced a number of well-characterized virulence factors, including proteases, fimbriae, and capsule [27]. Recently, a significant association was observed between a carrier of the rag locus and a highly virulent phenotype in a murine model of soft tissue destruction [3, 4, 10, 28].

In order to further determine whether the P. gingivalis rag locus was associated with periodontitis, we investigated the prevalence of P. gingivalis and rag locus distributions in periodontitis patients in this study. We detected 29 P. gingivalis out of 110 patient GCF samples. However, the prevalence of P. gingivalis was lower in localized chronic periodontitis patients (1.75%) and generalized chronic periodontitis patients (27%) [29]. We also suspected that the method of samples collection was insensitive, but others reported that the prevalence of P. gingivalis was high by this method [30, 31]. At the same time, the ratios of P. gingivalis in necrotizing periodontal patients (95%) were in accordance with other reports [32–34]. Among the 29 cases containing P. gingivalis, only 19 samples amplified the rag locus variants. And among 19 cases containing the rag locus, 18 (95%) were amplified from necrotizing periodontal patients and one (5%) from a generalized chronic periodontitis patient. All of the 19 cases containing the rag locus were from at least three sites with a PD of 8 to 10 mm, accompanying clearly visible plaque or BOP and CAL; at the same time, some rag locus carrier cases accompanied diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which indicated that the rag locus may be associated with severe periodontitis. Besides, we found that rag1 locus variants may be the prevalent genotype in Zhenjiang; however, other rag locus variants were also common in other regions [29, 34–37], which showed that the rag locus distribution had the same obvious regional differences as the bacteria resistance to antibiotics [38].

The rag locus has a restricted distribution within the species and lower G+C contents. Furthermore, the rag locus is located downstream of IS1126. As was well known that the insertion sequence (IS) is a mobile element contributing to gene transposition which could lead to the inactivation of genes, the transcriptional activation of dormant genes, and genomic rearrangements, which are the main causes of the pathogenicity and genetic diversity of bacterial populations [39–41], we speculated that the rag locus might have arisen from exogenous genes and obtained through transposition. In order to prove our speculations, a phylogenetic analysis was performed to determine the evolutionary relationships between the P. gingivalis rag locus and homologous sequences. Many proteins were analyzed, for example, RagA/B, Sus, and CirA. All of these proteins belonged to the family of TonB-linked outer membrane receptors which were involved in the recognition and active transport of specific external ligands [36]. In organisms, a TonB-linked outer membrane receptor was also co-transcribed with an outer membrane lipoprotein [42]. The co-distribution and co-transcription of ragA and ragB strongly suggested that they were functionally linked, and the products might form a complex on the outer surface of P. gingivalis, which was involved in a TonB-linked process. RagA, Sus, and CirA were involved in maltose uptake, and RagB was associated with the active transport of lactoferrin and transferrin iron sources. RagB was closely similar to RagB/SusD of Prevotella sp., Bacteroides sp., and Capnocytophaga sp. Furthermore, this tree also showed that branches 1 and 2 in cluster I were the paralogy, and in cluster III, the two branches were also paralogy, which indicated that ragA was highly similar to the TonB-dependent receptor of Bacteroides sp., and ragB was analogous to ragB/SusD of Prevotella sp., Bacteroides sp., and Capnocytophaga sp., respectively. To further determine the origin of the rag locus, the G+C contents of highly homologous genes to rag were analyzed. The analysis of G+C contents revealed that the G+C contents of the rag locus were under the average level of the P. gingivalis complete genome, including HmuR, and that the G+C contents of the rag locus were close to Bacteroides sp. Sus. Moreover, multiple alignments between the rag locus and Sus showed that the RagA and SusC were both constituted of three domains (TonB I, II, and III); and RagB and SusD were constituted of two domains: Lipoprotein and RagB/SusD, respectively. The amino acids were highly conserved, and our tests for selection showed that the rag locus were probably evolving under long-term purifying selection, which also indirectly indicated that the rag locus might arise from horizontal gene transfer.

From all of the evidence mentioned above, we could conclude that the rag locus was not duplicated by self-HmuR, but instead arose from Bacteroides sp. Sus via horizontal gene transfer. The exogenous rag locus promoted the P. gingivalis expression of virulence gene or the activation of dormant genes. Thus, P. gingivalis was differentiated into virulent and avirulent genotype. The rag locus-carried genotype may be associated with severe periodontitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the social development of Jiangsu province (Grant No. BS2007041), the SCI-Tech Innovation Team of Jiangsu University (Grant No. 2008-018-02), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30871193), the Natural Science Foundation of Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province, and the Innovation Fund for candidate of doctor in Jiangsu Province (Grant Nos. 09KJB310001 and CX09B_217Z, respectively), and the High-Level Creative Talent Development Project of Jiangsu Province (07-D-034).

We thank Yu Zhang, Hui Cao, Daoru Dong, Dr. F. Valiyeva, and Dr. Hu Xu for their editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

S. Wang, Phone: +86-511-85038140, FAX: +86-511-85038449, Email: sjwjs@ujs.edu.cn

H. Xu, Phone: +86-511-85038140, FAX: +86-511-85038449, Email: xuhx@ujs.edu.cn, Email: szl30@yeah.net

References

- 1.Griffen AL, Becker MR, Lyons SR, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and periodontal health status. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(11):3239–3242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3239-3242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall LM, Fawell SC, Shi X, Faray-Kele MC, Aduse-Opoku J, Whiley RA, Curtis MA. Sequence diversity and antigenic variation at the rag locus of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2005;73(7):4253–4262. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4253-4262.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genco CA, Cutler CW, Kapczynski D, Maloney K, Arnold RR. A novel mouse model to study the virulence of and host response to Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1991;59(4):1255–1263. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1255-1263.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffen AL, Lyons SR, Becker MR, Moeschberger ML, Leys EJ. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain variability and periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(12):4028–4033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4028-4033.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rylev M, Kilian M. Prevalence and distribution of principal periodontal pathogens worldwide. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):346–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loos BG, Mayrand D, Genco RJ, Dickinson DP. Genetic heterogeneity of Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis by genomic DNA fingerprinting. J Dent Res. 1990;69(8):1488–1493. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690080801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genco RJ, Loos BG. The use of genomic DNA fingerprinting in studies of the epidemiology of bacteria in periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18(6):396–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1991.tb02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang YJ, Yasui S, Yoshimura F, Ishikawa I. Multiple restriction fragment length polymorphism genotypes of Porphyromonas gingivalis in single periodontal pockets. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10(2):125–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1995.tb00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanley SA, Aduse-Opoku J, Curtis MA. A 55-kilodalton immunodominant antigen of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 has arisen via horizontal gene transfer. Infect Immun. 1999;67(3):1157–1171. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1157-1171.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis MA, Hanley SA, Aduse-Opoku J. The rag locus of Porphyromonas gingivalis: a novel pathogenicity island. J Periodontal Res. 1999;34(7):400–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis MA, Slaney JM, Carman RJ, Johnson NW. Identification of the major surface protein antigens of Porphyromonas gingivalis using IgG antibody reactivity of periodontal case–control serum. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6(6):321–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1991.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park OJ, Min KM, Choe SJ, Choi BK, Kim KK. Use of insertion sequence element IS1126 in a genotyping and transmission study of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(2):535–541. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.535-541.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maley J, Roberts IS. Characterisation of IS1126 from Porphyromonas gingivalis W83: a new member of the IS4 family of insertion sequence elements. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123(1–2):219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Airila-Månsson S, Söder B, Kari K, Meurman JH. Influence of combinations of bacteria on the levels of prostaglandin E2, interleukin-1beta, and granulocyte elastase in gingival crevicular fluid and on the severity of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2006;77(6):1025–1031. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes SC, Piccinin FB, Oppermann RV, Susin C, Nonnenmacher CI, Mutters R, Marcantonio RA. Periodontal status in smokers and never-smokers: clinical findings and real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification of putative periodontal pathogens. J Periodontol. 2006;77(9):1483–1490. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Northwest Dent. 2000;79(6):31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4(1):1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rüdin HJ, Overdiek HF, Rateitschak KH. Correlation between sulcus fluid rate and clinical and histological inflammation of the marginal gingiva. Helv Odontol Acta. 1970;14(1):21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lévesque C, Piché L, Larose C, Roy PH. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(1):185–191. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran SD, Rudney JD. Multiplex PCR using conserved and species-specific 16S rRNA gene primers for simultaneous detection of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(11):2674–2678. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2674-2678.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen T, Hosogi Y, Nishikawa K, Abbey K, Fleischmann RD, Walling J, Duncan MJ. Comparative whole-genome analysis of virulent and avirulent strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(16):5473–5479. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5473-5479.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13(5):555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persson GR, Imfeld T. Periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. Ther Umsch. 2008;65(2):121–126. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930.65.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seymour GJ, Ford PJ, Cullinan MP, Leishman S, Yamazaki K. Relationship between periodontal infections and systemic disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(Suppl 4):3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offenbacher S, Jared HL, O’Reilly PG, Wells SR, Salvi GE, Lawrence HP, Socransky SS, Beck JD. Potential pathogenic mechanisms of periodontitis associated pregnancy complications. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3(1):233–250. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campus G, Salem A, Uzzau S, Baldoni E, Tonolo G. Diabetes and periodontal disease: a case–control study. J Periodontol. 2005;76(3):418–425. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt SC, Kesavalu L, Walker S, Genco CA. Virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:168–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi X, Hanley SA, Faray-Kele MC, Fawell SC, Aduse-Opoku J, Whiley RA, Curtis MA, Hall LM. The rag locus of Porphyromonas gingivalis contributes to virulence in a murine model of soft tissue destruction. Infect Immun. 2007;75(4):2071–2074. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01785-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças IN, Silva MG. Prevalence and clonal analysis of Porphyromonas gingivalis in primary endodontic infections. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1332–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darby IB, Mooney J, Kinane DF. Changes in subgingival microflora and humoral immune response following periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28(8):796–805. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2001.280812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling LJ, Hung SL, Tseng SC, Chen YT, Chi LY, Wu KM, Lai YL. Association between betel quid chewing, periodontal status and periodontal pathogens. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2001;16(6):364–369. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302X.2001.160608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riep B, Edesi-Neuss L, Claessen F, Skarabis H, Ehmke B, Flemmig TF, Bernimoulin JP, Göbel UB, Moter A. Are putative periodontal pathogens reliable diagnostic markers? J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1705–1711. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01387-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torrungruang K, Bandhaya P, Likittanasombat K, Grittayaphong C. Relationship between the presence of certain bacterial pathogens and periodontal status of urban Thai adults. J Periodontol. 2009;80(1):122–129. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faghri J, Moghim Sh, Abed AM, Rezaei F, Chalabi M. Prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Bacteroides forsythus in chronic periodontitis by multiplex PCR. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10(22):4123–4127. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.4123.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulekci G, Leblebicioglu B, Keskin F, Ciftci S, Badur S. Salivary detection of periodontopathic bacteria in periodontally healthy children. Anaerobe. 2008;14(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakai VT, Campos MR, Machado MA, Lauris JR, Greene AS, Santos CF. Prevalence of four putative periodontopathic bacteria in saliva of a group of Brazilian children with mixed dentition: 1-year longitudinal study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17(3):192–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koebnik R. TonB-dependent trans-envelope signalling: the exception or the rule? Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(8):343–347. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su Z, Xu H, Zhang C, Shao S, Li L, Wang H, Qiu G. Mutations in Helicobacter pylori porD and oorD genes may contribute to furazolidone resistance. Croat Med J. 2006;47(3):410–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podglajen I, Breuil J, Casin I, Collatz E. Genotypic identification of two groups within the species Bacteroides fragilis by ribotyping and by analysis of PCR-generated fragment patterns and insertion sequence content. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(18):5270–5275. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5270-5275.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bik EM, Gouw RD, Mooi FR. DNA fingerprinting of Vibrio cholerae strains with a novel insertion sequence element: a tool to identify epidemic strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(6):1453–1461. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1453-1461.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guerrero C, Bernasconi C, Burki D, Bodmer T, Telenti A. A novel insertion element from Mycobacterium avium, IS1245, is a specific target for analysis of strain relatedness. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(2):304–307. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.304-307.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornelissen CN. Transferrin-iron uptake by Gram-negative bacteria. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d836–d847. doi: 10.2741/1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]