Abstract

Functional neuroendocrine tumors are often low-grade malignant neoplasms that can be cured by surgery if detected early, and such detection may in turn be accelerated by the recognition of neuropeptide hypersecretion syndromes. Uniquely, however, relief of peptic symptoms induced by hypergastrinemia is now available from acid-suppressive drugs such as proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs). Here we describe a clinical case in which time to diagnosis from the onset of peptic symptoms was delayed more than 10 years, in part reflecting symptom masking by continuous prescription of the PPI omeprazole. We propose diagnostic criteria for this under-recognized new clinical syndrome, and recommend that physicians routinely measure serum gastrin levels in persistent cases of PPI-dependent dyspepsia unassociated with H. pylori.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine carcinoma, Pancreatic tumor, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, Gastrin, Omeprazole

Background

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are generally characterised by slow onset of non-specific symptoms and consequent delay in diagnosis. With specific reference to gastrinomas, Ellison & Sparks showed in a prospective study that the era of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)—although highly effective symptomatic therapy for the neuroendocrine symptoms of gastrinoma—has been associated with upstaging of malignant disease at diagnosis [1]. A retrospective analysis reached the same conclusion based on correlations of case referral patterns over time [2]; however, the expected secondary incidence rise following diagnostic delay was not confirmed, casting doubt on a causal interpretation. Confusingly, in the largest clinical analysis of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome ever published, this same group reported no change in age of onset, delay in diagnosis (about 5 years) or frequency of complications following introduction of PPIs [3]. Since these negative conclusions could plausibly have been confounded by concurrent improvements in diagnostic technology and/or physician awareness, we present here an instructive case of malignant gastrinoma that clearly illustrates how a suboptimal index of suspicion can delay diagnosis to more than 10 years after the first presentation of reflux symptoms managed with PPIs.

Case Presentation

A 58-year-old Caucasian male presented in 2000 with a long history of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms since the 1990s; his past history was notable for hypertension and appendicectomy, and his family history was negative. Upper endoscopy showed gastroesophageal reflux disease, and a segment of Barrett’s esophagus was confirmed by biopsy. He was treated initially with the H2-receptor antagonist ranitidine, but this was soon changed to the PPI omeprazole (20 mg/day) due to inadequate pain control. His symptoms briskly recurred on discontinuing omeprazole, leading to indefinite continuation of this medication as long-term maintenance. Upper endoscopy was repeated every 2 years for monitoring. In 2001 the symptom complex evolved to include recurrent episodic abdominal pain of cramping nature associated with retching and prominent borborygmi. Diarrhea was not a feature; instead, constipation was reported, with abdominal X-rays showing subacute intestinal obstruction. Colonoscopy was unremarkable. The patient was followed up in a primary healthcare setting.

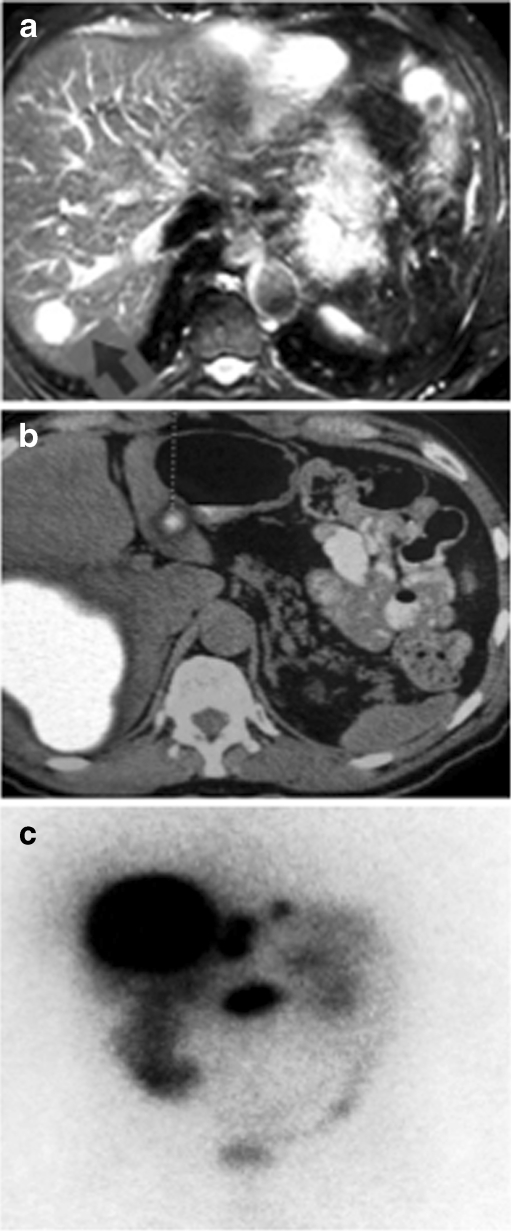

In March 2004 he presented again, this time with subacute right upper quadrant pain. A contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the hepatobiliary system revealed no abnormality apart from two small liver nodules, measuring 11 mm in segment VI, and 20 mm in segment VII, respectively, which were hypointense on plain T1-weighted images, and hyperintense with a ‘light-bulb’ appearance on plain T2-weighted images (Fig. 1a), with peripheral enhancement and central filling-in on post-contrast T1-weighted images. The radiological features were deemed typical of hemangiomas, so no biopsy was advised. Maintenance omeprazole was increased to 20 mg twice-daily, and the pain resolved.

Fig. 1.

a MRI liver in 2004 showing one of the lesions which was hyperintense with a typical ‘light-bulb’ appearance on plain T2-weighted images. b FDG-PET scan showing uptake in the liver and pancreatic lesions with regional lymph node involvement. c OctreoScan confirming metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

In 2007 the patient underwent a further reassessment for recurrent episodic abdominal discomfort. Upper endoscopy at this time confirmed persistent esophagitis with no frank ulceration; the previous changes of Barrett’s esophagus had resolved on long-term PPI. In January 2008 he was admitted to a tertiary referral centre for an acute exacerbation of abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed a febrile patient with mild tenderness over the right lower quadrant. Routine blood tests revealed a raised white cell count of 11.4x109/L (normal: 4.4–10.1x109/L) with neutrophilia, normal renal function and electrolytes including calcium; mildly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase of 123 U/L (normal: 42–110 U/L) and aspartate transaminase of 55 U/L (normal: 15–38 U/L), and normal bilirubin and clotting profile. Plain abdominal X-ray revealed a fecal-loaded colon with prominent small bowel loops. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to exclude diverticulitis; this revealed a 10 cm heterogenous mass spanning segments V, VI, VII and VIII of the right lobe of the liver, a second intrahepatic mass occupying segments VI and VII adjacent to it, and a pancreatic mass at the uncinate process with regional mesenteric lymphadenopathy. Tumor markers including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), prostate specific antigen (PSA) and Ca 19.9 were normal; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was slightly raised to 7.4 ng/ml (normal: < 5 ng/ml). The patient then underwent positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which showed hypermetabolic lesions in the liver, pancreas and mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 1b). Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the liver mass confirmed a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor; immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin, chromogranin and CD56 was positive. Other markers, including inhibin, c-kit, AFP, HEPA, CK7 and CK20, were negative.

Further neuroendocrine workup was performed after stopping PPI for two weeks. Fasting serum gastrin remained elevated (240 pg/ml; normal <113 pg/ml), with less marked elevations of chromogranin A (247 ng/ml; normal <160 ng/ml), and somatostatin (25 pg/ml; normal <22 pg/ml). Fasting plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide and glucagon, and urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and catecholamines were normal, but 24-hour urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid was raised. Gastric acid output studies were not performed. Somatostatin receptor imaging (OctreoScan) showed intense uptake in the uncinate process of the pancreas, and in the right lobe, segment II, III and caudate lobe of liver, compatible with a neuroendocrine tumor rich in somatostatin receptors (Fig. 1c).

In March 2008 the patient underwent the first of two laparotomies. Because of the symptomatic nature of the large hepatic metastases, partial hepatectomy was performed first. A 10 cm tumor was found in the right lobe of the liver, and smaller tumors were found in segment II and III; right hepatectomy was carried out with wedge resection of the segment II lesion, radiofrequency ablation of the segment III lesion, followed by wedge resection of segment III. Histopathologic examination confirmed a metastatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of low grade malignancy. Expression of the proliferation marker MIB-1 (Ki-67) was less than 5%. As expected, immunohistochemical studies were positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, serotonin and gastrin.

Whipple’s pancreatectomy and anastomosis was performed six weeks later, and a 5 cm uncinate process primary pancreatic islet-cell tumor removed. Pathology showed a well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with lymphovascular permeation and regional lymph node metastases; immunohistochemical staining again confirmed the positivity of neuroendocrine markers (Fig. 2). Based on the symptom diathesis, biochemical analyses and histopathological findings, a clinical diagnosis of malignant pancreatic gastrinoma was made. Post-surgical follow-up showed normal gastrin and chromogranin levels. Urinary 5-HIAA level was much reduced compared to baseline, though still marginally raised. Octreoscan showed uptake at the liver resection margin, but no definitive lesion was confirmed by MRI. One year later, the patient remained asymptomatic.

Fig. 2.

a Microscopic examination of the pancreatic primary, showing well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with regional lymph node involvement. The tumour cells are arranged in sheets with vascular stroma. They have mild nuclear pleomorphism, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric nuclei. Regional lymph node involvement is present (not shown). Original magnification x400. b Immunohistochemical staining of the pancreatic primary, showing positive neuroendocrine marker synaptophysin. Original magnification x400

Discussion

The earliest presenting symptoms of functional PNETs depend on the consequences of their hormonal output. In gastrinomas the clinical presentation depends on the effects of constitutive gastrin production—mainly, in historical studies, gastric acid hypersecretion—and that of any other gut neuropeptide(s) released. Although the classical Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (ZES) described multiple and/or ectopic peptic ulcers [4, 5], a recent study showed that the usual presenting symptoms of gastrinomas now feature abdominal pain, diarrhea, or both in 75%, 73% and 55% of patients respectively, with heartburn also reported in 44% [3]. Moreover, even prior to the advent of PPI therapy, up to 25% of malignant gastrinoma patients have no demonstrable peptic ulceration [6].

Up to a quarter of all gastrinomas are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN 1), which is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Although gastrinoma is the most common pancreatic islet cell tumour type in MEN 1, the most crucial component and usual initial presentation of the syndrome tends to be primary hyperparathyroidism, present in over 90% of MEN 1 patients [7]. Moreover, islet cell tumours in MEN 1 are typically multiple. In view of normocalcemia, solitary nature of the gastrinoma, lack of associated clinical features and negative family history, the current case was considered a sporadic occurence.

We submit that the present case illustrates the features of a new clinical syndrome of ‘PPI-masked gastrinoma’. First, the patient’s symptoms are predominantly not those of hyperacidity, but rather those of hypergastrinemia—recurrent abdominal pain, gastrointestinal hypermotility, borborygmi, and gallbladder contraction. In contrast to historical ZES descriptions, effective PPI-dependent suppression of massive gastric acid hypersecretion should reduce both peptic ulceration and diarrhea [8, 9], consistent with the present case in which the only symptom of low gastric pH was occasional heartburn. Indeed, omeprazole has long been recognized to be a more tolerable and effective therapy for gastrinoma symptoms than is the gastrin-inhibitory somatostatin analog, octreotide [10]. Although we would predict prominent gastric mucosal rugosity without ulceration to be another correlate of this syndrome [11], we have not documented this.

Second, the delay in diagnosis of this case from the time of symptom onset is typical of PPI-masked gastrinoma. This iatrogenic complication—in which, ironically, an established ZES supportive therapy [12, 13] is used for symptom relief without knowledge of the etiologic diagnosis, culminating in eventual diagnosis of more advanced disease with shorter average 5-year survival, perhaps reflecting a lead time effect—should be a matter of serious professional concern. In the present case the diagnosis of gastrinoma was masked by PPI-dependent reversion of hyperacidity, leaving only the nonspecific syndrome of intermittent abdominal pain and borborygmi. Indeed, so minimally symptomatic was the PPI-treated patient for several years that the early radiologic detection of liver metastases was misinterpreted, and the final diagnosis of malignancy was only made in response to painful liver capsular distension by massive tumor progression 4 years later. Since half of all ZES presentations occur in the absence of detectable liver metastases [14], early recognition of hypergastrinemic symptoms prior to carcinomatosis would seem the only feasible pathway to cure.

Third, the ease of misdiagnosing PPI-masked gastrinoma as an atypical carcinoid syndrome or even as a non-functional metastatic PNET is well illustrated by the present case, providing an explanation for the recent observation by Corleto et al of declining rates of gastrinoma diagnosis associated with rising referral rates for other PNETs. Multiple neuropeptide hypersecretion is often seen in neuroendocrine cancer [15]; this includes that of serotonin production by gastrinomas [16], as well as that of hypergastrinemia occurring in association with carcinoids [17]. It follows from these observations that the heterogeneous clinical presentations of neuroendocrine tumors could well be explained in part by unique multi-neuropeptide signatures of individual tumors. We note that a worse prognosis has been associated with secretion of multiple neuropeptides by sporadic PNETs [18], further emphasizing the hazards of late diagnosis occurring as a result of PPI-masked symptoms.

The suboptimal sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors by conventional imaging techniques also adds to the diagnostic dilemma. For example, the sensitivity of MRI in detecting these tumors is reported to vary between 29% to 57% only [19–21]. MRI visualization of islet cell tumors, which have a rich arterial blood supply [21], depends on their hypervascularity relative to the surrounding normal pancreatic tissue [17], but it is difficult to distinguish them from other vascular lesions including hemangiomas. In the present case, tumors already present on MRI liver in 2004 were misinterpreted as benign hemangiomas (Fig. 1a). Curiously, FDG-PET is reputed to be less useful in well-differentiated slow-growing neuroendocrine tumors [18, 19] but was of value in our case; newer positron-emitter radiopharmaceuticals including 11C 5HTP and 11C L-DOPA appear more sensitive [20]. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is superior to ultrasound, CT, MRI, and FDG-PET in terms of both sensitivity and specificity [22], though 11C 5HTP-PET may prove even more sensitive.

In summary, the present case supports other clinical observations [23, 24] and series [1, 25] attesting to the evolution of a new iatrogenic syndrome caused by PPI-dependent suppression of peptic symptoms. We propose a diagnostic triad for this novel syndrome comprising (i) non-peptic symptoms in hypergastrinemic patients receiving maintenance PPI, (ii) late-stage presentation of metastatic PNET, and (iii) diagnostic confusion with non-gastrinoma PNETs. Despite the negative finding by Roy et al with respect to diagnostic delay in PPI-treated gastrinomas [3], we submit that this emerging entity is indeed valid, and encourage a higher level of awareness by clinicians using PPIs to treat chronic non-H. pylori-associated hypergastrinemic dyspepsia, especially in middle-aged patients with unremitting, albeit non-specific, gastrointestinal symptoms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Kjell Oberg of Karolinska Institute for helpful discussions about this case.

Consent Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions HW and RE (guarantor) drafted the report. TY and PC participated in analysis. IN and GC did immunohistochemistry. PH reported imaging. All authors conceived, read and revised the manuscipt.

Abbreviations

- PNET

pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- ZES

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome

References

- 1.Ellison EC, Sparks J. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome in the era of effective acid suppression: are we unknowingly growing tumors? Am J Surg. 2003;186:245–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corleto VD, Annibale B, Gibril F, et al. Does the widespread use of proton pump inhibitors mask, complicate and/or delay the diagnosis of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1555–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, et al. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Clinical presentation in 261 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:379–411. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellison EH, Wilson SD. The Zollinger–Ellison syndrome: re-appraisal and evaluation of 260 registered cases. Ann Surg. 1964;160:512–30. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196409000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zollinger RM, Ellison EC, O’Dorisio TM, et al. Thirty years’ experience with gastrinoma. World J Surg. 1984;8:427–35. doi: 10.1007/BF01654904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen RT, Gardner JD, Raufman JP, et al. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome: current concepts and management. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:59–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA (2008) Cancer: principles of oncology. 8th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Welkins.

- 8.Blonski WC, Katzka DA, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion presenting as a diarrheal disorder and mimicking both Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and Crohn’s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:441–4. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Feigenbaum KM, et al. Gastric secretion in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Correlation with clinical expression, tumor extent and role in diagnosis—-a prospective NIH study of 235 patients and a review of 984 cases in the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001;80:189–222. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maton PN. Use of octreotide acetate for control of symptoms in patients with islet cell tumors. World J Surg. 1993;17:504–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01655110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukui T, Nishio A, Okazaki K, et al. Gastric mucosal hyperplasia via upregulation of gastrin induced by persistent activation of gastric innate immunity in major histocompatibility complex class II deficient mice. Gut. 2006;55:607–15. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.077917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metz DC, Comer GM, Soffer E, et al. Three-year oral pantoprazole administration is effective for patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and other hypersecretory conditions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:437–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz DC, Sostek MB, Ruszniewski P, et al. Effects of esomeprazole on acid output in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome or idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2648–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banasch M, Schmitz F. Diagnosis and treatment of gastrinoma in the era of proton pump inhibitors. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:573–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0884-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lodish MB, Powell AC, Abu-Asab M, et al. Insulinoma and gastrinoma syndromes from a single intrapancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1123–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurevich L, Kazantseva I, Isakov VA, et al. The analysis of immunophenotype of gastrin-producing tumors of the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract. Cancer. 2003;98:1967–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bamba T, Kosugi S, Kanda T, et al. Multiple carcinoids in the duodenum, pancreas and stomach accompanied with type A gastritis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2247–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i15.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ardill JE, Erikkson B. The importance of the measurement of circulating markers in patients with neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas and gut. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:459–62. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibril F, Reynolds JC, Doppman JL, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: its sensitivity compared with that of other imaging methods in detecting primary and metastatic gastrinomas A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:26–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-1-199607010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmer T, Stolzel U, Bader M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in the preoperative localisation of insulinomas and gastrinomas. Gut. 1996;39:562–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Norton JA, et al. Prospective study of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and its effect on operative outcome in patients with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1998;228:228–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199808000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson NW, Eckhauser FE, Vinik AI, et al. Cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas and liver. Ann Surg. 1984;199:158–64. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198402000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santen S, Soest EJ, Busch OR, et al. A woman with shock as first sign of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2007;151:478–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tartaglia A, Vezzadini C, Bianchini S, et al. Gastrinoma of the stomach: a case report. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:211–6. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:35:3:211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton JA, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery to cure the Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:635–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]